Abstract

Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) is the major mammalian enzyme in DNA base excision repair that cleaves the DNA phosphodiester backbone immediately 5′ to abasic sites. Recently, we identified APE1 as an endoribonuclease that cleaves a specific coding region of c-myc mRNA in vitro, regulating c-myc mRNA level and half-life in cells. Here, we further characterized the endoribonuclease activity of APE1, focusing on the active site center of the enzyme previously defined for DNA nuclease activities. We found that most site-directed APE1 mutant proteins (N68A, D70A, Y171F, D210N, F266A, D308A, H309S), which target amino acid residues comprising the abasic DNA endonuclease active site pocket, showed significant decreases in endoribonuclease activity. Intriguingly, the D283N APE1 mutant protein retained endoribonuclease and abasic site single-stranded RNA (AP-ssRNA) cleavage activity, with concurrent loss of AP site cleavage activity on dsDNA and ssDNA. The mutant proteins bound c-myc RNA equally well as wild-type (WT) APE1, with the exception of H309N, suggesting that most of these residues contributed primarily to RNA catalysis, and not RNA binding. Interestingly, both endoribonuclease and ssRNA AP site cleavage activity of wild-type APE1 was present in the absence of Mg2+, while ssDNA AP site cleavage required Mg2+ (optimally at 0.5 to 2.0 mM). We also found that a 2′-OH on the sugar moiety was absolutely required for RNA-cleavage by WT APE1[comment: I think I would leave this result out of the abstract), consistent with APE1 leaving a 3′-PO42− group following cleavage of RNA. Altogether, our data support the notion that a common active site is shared for endoribonuclease and other nuclease activities of APE1; however, we provide evidence that the mechanisms for cleaving RNA, AP-ssRNA, and abasic DNA by APE1 are not identical, an observation that has implications for unraveling the endoribonuclease function of APE1 in vivo.

Keywords: Endoribonuclease, APE1, RNA

Introduction

There is increasing evidence that endonucleolytic cleavage of mRNA plays a critical role in eukaryotic and mammalian gene expression1–4. Recent reports on several enzymes possessing endoribonucleolytic activities have highlighted their roles in mediating the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression5–9. Endoribonucleases that cleave mRNA appear to be induced by stress signals leading to profound effects on cell growth and disease development due to their abilities to control relevant transcript levels4,10. For instance, RNase L becomes activated by 2′,5′-linked oligoadenylates (2–5A) after interferon signaling in response to viral infection11. RNase L activation, in turn, destabilizes mRNAs of ribosomal proteins and the RNA-binding protein, HuR12,13. Similarly, Polysomal Ribonuclease 1 (PMR1) regulates β-globin mRNA upon phosphorylation by an activated c-Src14.

We have recently identified apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) as an endoribonuclease that cleaves c-myc mRNA in vitro15. We further showed that APE1 can regulate c-myc mRNA level and half-life in cells, possibly via this endoribonuclease activity. APE1 is a multi-functional protein with roles in DNA base excision repair and in redox activation of DNA-binding transcription factors16. The functional regions for the DNA repair and redox functions of APE1 seem to be independent of each other17. The abasic DNA endonuclease domain of the human protein consists of several important amino acids between Asn68 and His309 as determined by X-crystallography18 and functional studies19–23. On the other hand, the N-terminal region of APE1 harbors the redox center, which consists of critical cysteine residues (Cys65 and Cys93) important for activating various transcription factors implicated in apoptosis and cell growth (e.g., AP-1, Egr-1, NF-kappaB, p53, c-Jun, and HIF)16,24. APE1 has been found to possess multiple DNA nuclease activities, including 3′ phosphodiesterase25, 3′–5′ exonuclease26, and 3′ phosphatase25,27,28. In addition, RNase H-type activity of APE1 has been reported29. Studies indicate that the exonuclease and abasic DNA endonuclease activities share a common active site, with both activities sensitive to mutations in critical amino acids such as Glu96, Asp210, and His30930. The fact that most, if not all, of its nuclease activities share a common active site center makes it challenging to study the contribution and significance of each nuclease activity separately, including the recently discovered single-stranded15 and abasic single-stranded31 RNA-cleaving activities of APE1 in cells.

We have previously shown that H309N and E96A mutants of APE1 have no RNA-cleaving activity, suggesting that the domain containing this enzymatic function of APE1 resides in the same region (active site) as its other nuclease activities. Furthermore, the RNA-cleaving activity of APE1 is active in the absence of magnesium32, which is in stark contrast to AP-dsDNA endonuclease activity where magnesium is essential33. These results provide hints about possible differences in the mechanism for RNA-cleaving and AP-dsDNA endonuclease activities of APE1.

This study was undertaken to investigate the roles played by several key DNA nuclease active site amino acids in the endoribonuclease activity of APE1, with the goal being to understand the catalytic mechanism for RNA-cleavage by APE1. Our results show that, many, but not all, amino acid residues critical for AP-dsDNA incision are also important for the endoribonuclease activity of APE1. Our results have implications for understanding the structural basis of RNA-cleavage by APE1, as well as for dissecting the significance of the endoribonuclease function of APE1 in vivo.

Results

APE1 active site residues participate in both abasic double-stranded DNA incision and endoribonuclease activities

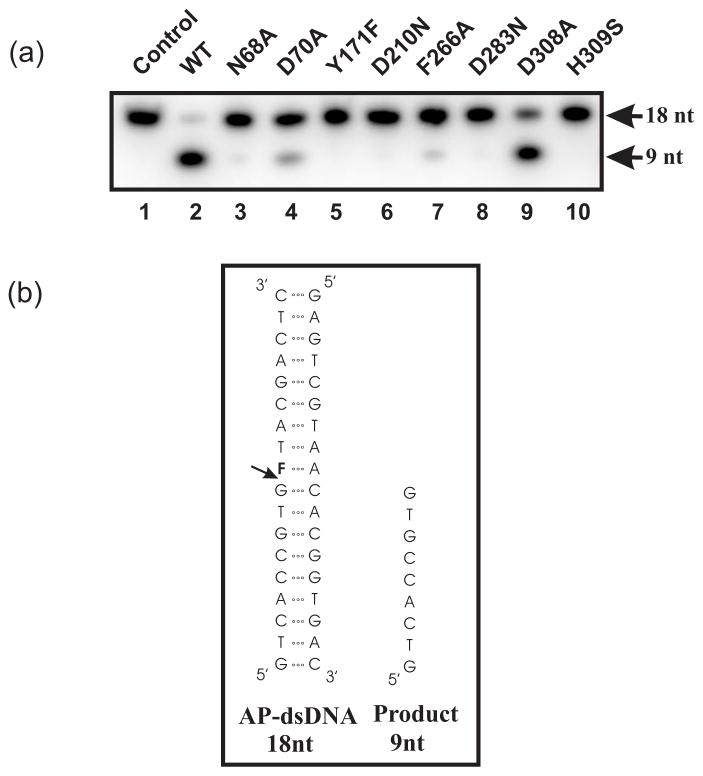

Recombinant wild-type (WT) APE1 and APE1 structural mutants containing a single site-specific amino acid change in the active site previously shown to be important for abasic double-stranded DNA (AP-dsDNA) endonuclease activity (N68A, D70A, Y171F, D210N, F266A, D283N, D308A, and H309S) were purified to near homogeneity and analyzed for purity on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel as described21. The dsDNA AP site cleavage activity of these APE1 structural mutants was first assessed using a previously employed 18 base-pair AP-dsDNA substrate34 (Fig. 1). AP-dsDNA endonuclease activitiy was essentially abolished in the N68A, Y171F, D210N, D283N, and H309S mutants, whereas significant reduction in activity was seen with the D70A, F266A and D308A mutants. The reduction in AP-dsDNA endonuclease activities observed with these APE1 structural mutants correlated well with previous studies (Table 1)19–23, indicating the importance of these residues in AP-dsDNA incision activity. The AP-dsDNA endonuclease results are shown in Fig. 1a and the quantitative summary is reported in Table 1. AP-dsDNA endonuclease activities were calculated by quantifying the ratio of the density of the product over those of the substrate plus product.

Fig. 1.

Abasic dsDNA endonuclease activity of the structural mutants of APE1. (a) Abasic dsDNA endonuclease activity of wild-type (WT) APE1 and APE1 structural mutants was assessed as described in the Materials and Methods. 0.14 nM of recombinant proteins (lanes 2 to 10) was incubated with 5′-γ-32P-radiolabeled abasic ds DNA. The 18-nt abasic dsDNA substrate and the 9-nt incised product are shown by arrows. (b) Structure and sequence of the abasic double-stranded DNA (AP-dsDNA) substrate and the 9-nt single stranded product are shown. The 18-mer oligonucleotide contains the model analog of an abasic site, tetrahydrofuran (F).

Table 1.

Summary of fold reduction in endoribonuclease and abasic dsDNA incision activities of APE1 structural mutants as compared to the wild-type APE1.

| APE1 structural mutants | Fold reduction in abasic dsDNA incisiona | Fold reduction in abasic dsDNA incisionb | Fold reduction in endoribonuclease activity against c-myc CRDc |

|---|---|---|---|

| N68A | 60023 | AB | AB |

| D70A | UDd | 6.7 | AB |

| E96A | 600–10000021,30 | UD | AB15 |

| Y171F | 500021 | AB | AB |

| D210N | 2500021 | AB | AB |

| N212A | UC19 | UD | UD |

| F266A | 620 | 30.4 | AB |

| D283N | 1022 | AB | UC |

| D308A | 5–2521,33 | 1.4 | AB |

| H309N | 10000030 | UD | AB15 |

| H309S | UD | AB | UD |

UD denotes undetermined; AB denotes abolished; UC denotes unchanged activity as compared to that of the wild-type APE1.

Information obtained from the literature.

Data obtained from Fig. 1a and replicates.

Data obtained from Fig. 2b and replicates.

For D70R mutant, the fold-reduction was ~ 27-fold23.

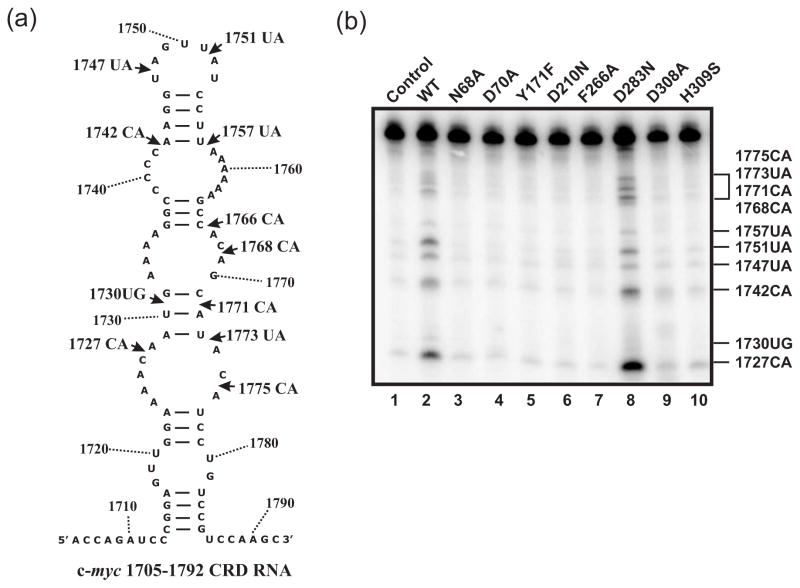

We next assessed the same panel of APE1 structural mutants for their ability to cleave 5′-32P-labeled c-myc CRD RNA substrate (Fig. 2a). To quantitatively compare the endoribonuclease activity of APE1 structural mutants to WT APE1, we measured the intensity of the decay products 1742CA, 1747UA, and 1751UA. All of the mutants exhibited abrogated endoribonuclease activity, with the notable exception of the D283N mutant (Fig. 2b and Table 1). These results showed that most of the amino acid residues important for abasic dsDNA incision are also critical for the endoribonuclease activity of APE1.

Fig. 2.

Structural mutants of APE1 display reduced endoribonuclease activity. (a) Secondary structure and sequence of c-myc-1705–1792 CRD is shown. Arrows indicate the cleavage sites of WT APE1. (b) Endoribonuclease assay was carried out on c-myc CRD RNA with APE1 and its structural mutants as described in the Materials and Methods. 1.4 μM of recombinant protein (lanes 2 to 10) was tested against 25 nM of 5′-γ-32P-radiolabeled c-myc-1705–1792 CRD in a total reaction volume of 20 μl for 25 min at 37°C. Numbers on the right indicate the cleavage sites generated by APE1.

Most APE1 active site residues are not individually critical for c-myc CRD RNA binding

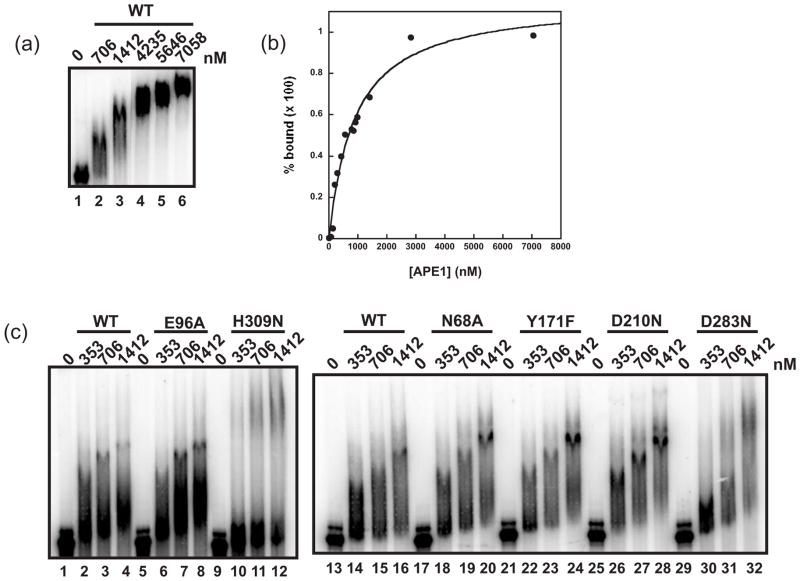

The reduced endoribonuclease activity of the structural mutants reported in Fig. 2b could be due to their reduced ability to bind RNA and/or a deficiency in catalysis. To evaluate the first premise, the ability of these structural mutants to bind c-myc CRD RNA was assayed by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA).

Experiments were performed initially to optimize the binding activity of APE1 on c-myc CRD RNA. We found that varying pH from 6.0–7.4 or adding detergents such as Triton X-100 had no effect, while the addition of heparin completely abolished the binding of APE1 to c-myc CRD RNA (data not shown). We then assayed WT APE1 for its ability to bind c-myc CRD RNA. At 706 and 1412 nM, a slower-migrating RNA-APE1 complex was observable as a smear (lanes 2 and 3, Fig. 3a), while at concentrations above 1412 nM, APE1 appeared to bind all of the RNA substrate resulting in the formation of a single RNA-APE1 complex (lanes 4–6, Fig. 3a). A saturation binding curve was generated from replicate experiments using the WT APE1 concentrations from 0 to 1412 nM (Fig. 3b). Fitting the saturation binding data using the Hill equation, we found that the dissociation constant, Kd, of WT APE1 binding c-myc CRD RNA was 880 ± 113 nM. The Hill coefficient was determined to be 1.0, suggesting that one molecule of APE1 binds one molecule of c-myc CRD RNA. Our findings of the progressive shift of the APE1-RNA complex upon increasing concentrations of APE1 has similarly been reported using a 58 nt single-stranded RNA29, and this may reflect the on and off binding rate of the protein (i.e. the instability of the complex). Interestingly, the Kd of APE1 binding to c-myc CRD RNA is similar to that of the RNA-binding protein CRD-BP, a protein previously shown to specifically bind c-myc CRD RNA35. A number of studies have shown that the Kd of APE1 for binding to DNA substrates is in the range of 0.87 to 125 nM20,36–38, suggesting that APE1 has a lower affinity for RNA substrates.

Fig. 3.

Ability of APE1 and structural mutants to bind c-myc CRD RNA. Increasing amount of WT APE1 or APE1 structural mutants were tested against 50 nM of 32P-internally radiolabeled c-myc 1705–1886 CRD RNA in a total binding volume of 20 μl for 15 min at 35°C in a standard electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as described in the Materials and Methods. (a) EMSA shows the binding of WT APE1 from 0 to 7058 nM. (b) Binding activity of WT APE1 was quantified comparing the relative amount of radiolabeled unbound RNA shifted to the slower migrating bound RNA. Data obtained was then used to plot the saturation binding curve as shown. (c) EMSA shows the ability of various concentrations of WT APE1 (lanes 2 to 4 and 14 to 16), E96A (lanes 6 to 8), H309N (lanes 10 to 12), N68A (lanes 18 to 20), Y171F (lanes 22 to 24), D210N (lanes 26 to 28), and D283N (lanes 30 to 32) to bind 32P-labeled c-myc CRD RNA.

We next evaluated the relative ability of the panel of APE1 structural mutants to bind c-myc CRD RNA. We employed protein concentrations that were in the linear range for binding to the RNA substrate by WT APE1 (0 to 1412 nM) (Fig. 3a and b). We reasoned that if there are differences in the binding affinity amongst the mutant proteins, it would most likely be observed in this concentration range. The left panel in Fig. 3c shows that both WT APE1 (lanes 2–4) and E96A (lanes 6–8) proteins exhibit similar binding affinities for c-myc CRD RNA, with 50–60% of c-myc RNA bound. In contrast, H309N (lanes 10–12) showed reduced binding, with 20–35% of c-myc RNA bound. We found that N68A (lanes 18–20), Y171F (lanes 22–24), and D210N (lanes 26–28) all displayed RNA binding affinities comparable to WT APE1 (lanes 2–4 and lanes 14–16). Interestingly, at lower concentrations (353 nM and 706 nM) (lanes 30 and 31), the D283N mutant protein showed a modest decrease in binding, with 30–40% of c-myc RNA bound. At the higher concentration (1412 nM) (lane 32), the RNA binding affinity of D283N became comparable to WT APE1 (lanes 2–4 and lanes 14–16) (Fig. 3c).

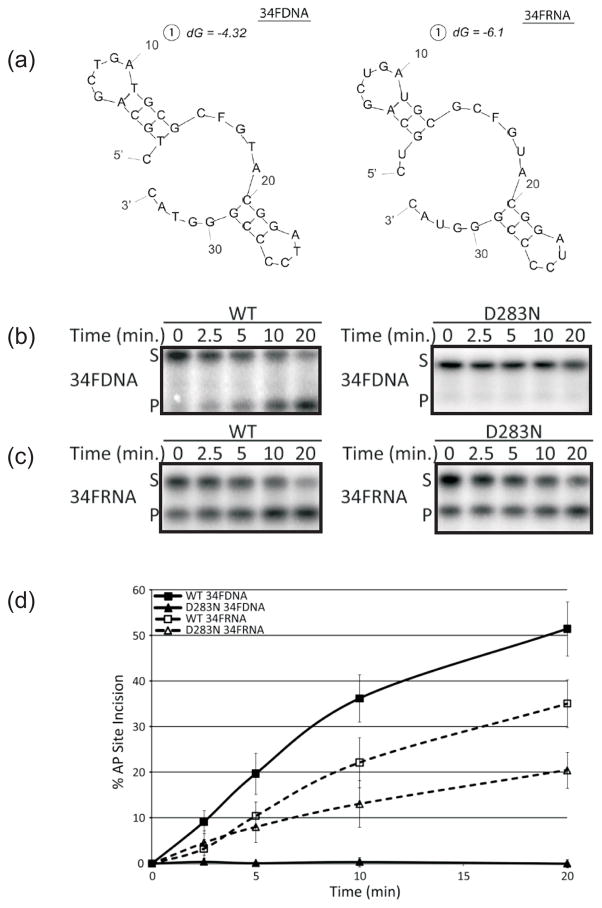

APE1 D283N active site mutation abolishes AP-ssDNA cleavage, but retains AP-ssRNA cleavage activity

Mutation at D283 has been consistently shown to negatively affect the AP-dsDNA endonuclease activitiy of APE1 (Fig. 1a)22,33,39,40. Our results above, however, indicate that the D283N mutant retains strong endoribonuclease activity on c-myc CRD RNA, comparable to that of the WT protein (Fig. 2b). We therefore wanted to assess the effect of the D283N mutation on AP-ssDNA and AP-ssRNA cleavage, as WT APE1 possesses AP site incision activity on both forms of nucleic acid31. Using single-stranded 34mer substrates of matching base sequence, but varying sugar composition (deoxyribose vs. ribose) (Fig. 4a), we compared the AP site incision activity of WT and D283N APE1. We found that the ssDNA AP site incision activity of D283N was severely diminished (~50 fold, WT specific activity of 747±35 × 105 pmol min−1 mg−1 and D283N specific activity of 15.5±11 × 105 pmol min−1 mg−1) (Fig. 4b and d), while ssRNA AP-site incision activity of D283N was only mildly affected (at best ~1.2 fold, WT specific activity of 37±8 × 104 pmol min−1 mg−1 and D283N specific activity of 29±7 × 104 pmol min−1 mg−1) (Fig. 4c and d). These results are consistent with the differential incision activities observed for D283N on AP site containing dsDNA (Fig. 1) versus c-myc RNA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 4.

Abasic single-stranded DNA and RNA endonuclease activities of WT APE1 and the D283N mutant. (a) Predicted secondary structures of 34FDNA (left panel) and 34FRNA (right panel) as determined using Mfold. F denotes position of abasic site analog tetrahydrofuran. (b) AP-ssDNA endonuclease activity of WT and D283N APE1. Time course reactions contained 15 pM APE1 WT or D283N protein, 200 fmol 5′-γ-32P-radiolabeled 34FDNA, and were incubated at 37°C for various times as shown. S denotes substrate position and P denotes product position. (c) AP-ssRNA endonuclease activity of WT and D283N APE1. Time course reactions contained 1.5 nM APE1 WT or D283N protein, 200 fmol 5′-γ-32P-radiolabeled 34FRNA, and were incubated at 37°C for various times as shown. S denotes substrate position and P denotes product position (we note the high degree of background product in the 0 min time point control). (d) Graph depicting WT and D283N APE1 time course incision kinetics on 34mer AP-ssDNA and 34mer AP-ssRNA. Average values with standard deviations of at least 3 independent experiments were plotted.

RNA catalysis mechanism of APE1

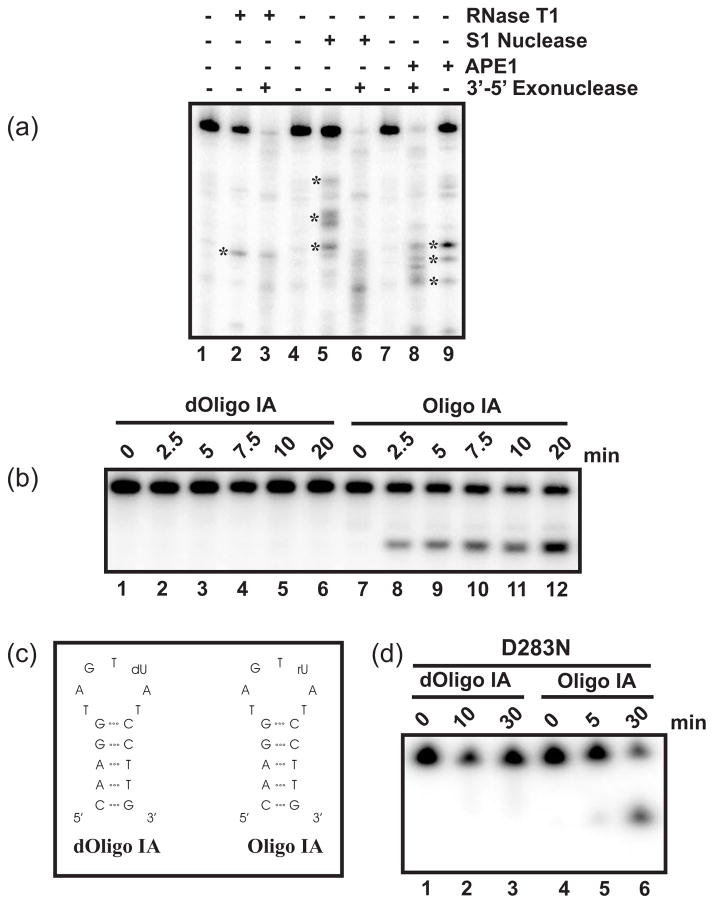

To determine whether WT APE1 generates RNA products with a 3′-PO42− or a 3′-OH group, we adopted the method described by Schoenberg and co-workers using snake venom exonuclease to digest only products bearing a 3′-OH41. Fig. 5a shows that the distinct product generated by RNase T1 (asterisk in lane 2) remained visible after digestion with snake venom exonuclease (lane 3), consistent with the fact that RNase T1 generates products with 3′-PO42−. In contrast, S1 nuclease generated products (marked with asterisks in lane 5) were completely degraded upon treatment with snake venom exonuclease (lane 6), consistent with the notion that S1 nuclease generates products with 3′-OH. The distinct decay products generated by APE1 (marked with asterisks in lane 9) were still visible upon treatment with snake venom exonuclease (lane 8), consistent with WT APE1 generating RNA products with 3′-PO42− groups.

Fig. 5.

RNA catalytic reaction mechanism of APE1. (a) APE1 generates RNA products with 3′-PO42−. 350 fmol 5′-labeled c-myc CRD RNA was digested with 1 U RNase T1 (lanes 2 and 3) for 1 min at 37°C, or with 10 U S1 nuclease (lanes 5 and 6) or 8.5 μM WT APE1 (lanes 8 and 9) for 5 min at 37°C under the standard RNA?? [specify??] endonuclease assay. The products were then incubated with 3 × 10−5 U snake venom exonuclease for 10 min at 25°C (lanes 3, 6, and 8), and electrophoresed on an 8% polyacrylamide/urea gel. Asterisks designate those products generated by RNase T1 (lane 2), S1 nuclease (lane 5), or APE1 (lane 9) that were monitored for exonuclease degradation. (b) Endoribonuclease activity of APE1 requires 2′-OH on the sugar moiety. 1.4 μM of APE1 was tested against 25 nM of 5′-γ-32P-radiolabeled dOligo IA (lanes 1–6) or Oligo IA (lanes 7–12) in a total reaction volume of 20 μl for varying time points at 37°C. (c) Secondary structure of dOligo IA and Oligo IA as predicted using Mfold. (d) 1.4 μM of D283N APE1 was tested against 25 nM of 5′-γ-32P-radiolabeled dOligo IA (lanes 1–3) or Oligo IA (lanes 4–6) in a total reaction volume of 20 μl for varying time points at 37°C. Result shown is representative of 3 independent experiments.

In a general acid-base mediated reaction mechanism, which produces RNA intermediates with 3′-PO42−, a 2′-OH group is required as a potential provider of the catalytic nucleophile. To better understand the mechanism of APE1 RNA catalysis, we implemented the use of two different RNA substrates, dOligoIA and OligoIA (Fig. 5c). Our results showed that when challenged with dOligoIA, containing a target Uridine at base position 10 linked to a deoxyribose moiety (dUpA), the WT APE1 was unable to produce any decay products (lanes 1–6, Fig. 5b). However, when challenged with OligoIA, containing a Uridine at base position 10 linked to a ribose group (rUpA), and thus a 2′-OH, the WT APE1 was able to generate an increasing amount of the expected cleavage product over time (lanes 7–12, Fig. 5b). Our results indicate that a 2′-OH in the sugar moiety is essential for APE1-mediated RNA catalysis.

To further understand the mechanism of endoribonuclease activity of APE1 and to elucidate the effect of mutation of D283 on APE1 RNA nuclease activity, we conducted the following experiment. We challenged D283N APE1 mutant with dOligoIA and OligoIA as described in Fig. 5. Our results showed that when D283N was incubated with dOligoIA, no distinct product was observed (lanes 1–3, Fig. 5d). However, when D283N APE1 was challenged with OligoIA, an increasing amount of the expected cleavage product was observed over time (lanes 4–6, Fig. 5d). These results are similar to what was observed with the WT APE1 protein (Fig. 5b), and suggest that mutation of D283 does not affect the ability of APE1 to use the 2′-OH in the sugar moiety for RNA catalysis.

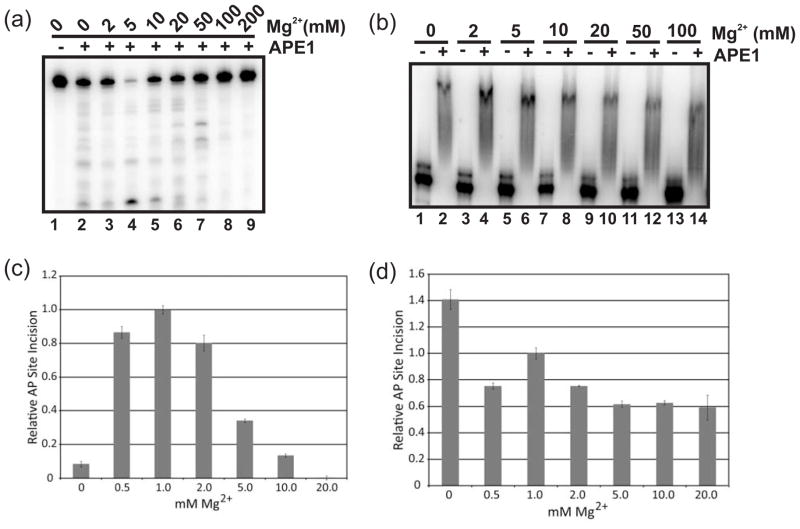

Mg2+ modulates APE1 nuclease activities

To understand the role that Mg2+ plays in the endoribonuclease activity of WT APE1, we first examined what effect increasing concentrations of the divalent metal had on APE1 cleavage of c-myc CRD RNA. APE1 exhibited RNA incision activity in the absence of Mg2+ (Fig. 6a, lane 2), while displaying highest activity at 5 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 6a, lane 4), consistent with our previous fluorometric assay measuring endoribonuclease activity of APE132. At concentrations greater than 5 mM (Fig. 6a, lanes 5–7), Mg2+ caused a gradual decrease in the endoribonuclease activity of APE1. At the highest concentrations (100 mM and 200 mM, lanes 8 and 9 in Fig. 6a), Mg2+ completely inhibited the RNA-cleaving activity of APE1. We also observed a change in the RNA cleavage pattern at 20 mM or 50 mM Mg2+ (lanes 6 and 7, Fig. 6a), suggesting the metal ion may either alter the RNA secondary structure or RNA-binding by APE1. To explore the latter hypothesis, we employed the EMSA to assess the role that Mg2+ plays in RNA complex formation by APE1. Fig. 6b shows that neither the nature of the complex nor the binding affinity of APE1 was dramatically altered by high Mg2+ levels. We therefore conclude that the altered RNA cleavage pattern observed is likely due to alterations in the RNA secondary structure imposed by the higher concentrations of Mg2+, resulting in an alternate incision site.

Fig. 6.

Effects of magnesium on the endoribonuclease, RNA binding, AP-ssDNA, and AP-ssRNA endonuclease activities of APE1. (a) 1.4 μM of APE1 (lanes 2 – 9) was tested against 25 nM of 5′-γ-32P-radiolabeled c-myc CRD RNA in a total reaction volume of 20 μl for 25 min at 37°C. Each lane contains a different magnesium concentration as indicated. (b) WT APE1 was tested against 50 nM of 32P-internally radiolabeled c-myc CRD RNA in a total volume of 20 μl for 15 min at 35°C in a standard EMSA under increasing concentrations of Mg2+. (c) Graph of relative AP-ssDNA incision by WT APE1 under various Mg2+ concentrations. 15 pM WT APE1 was incubated with 200 fmol 5′-γ-32P-radiolabeled 34FDNA in buffer containing 0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 2 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM, or 20 mM Mg2+ at 37°C for 5 min. Average values with standard deviations of at least 3 independent experiments are plotted relative to 1 mM Mg2+. (d) Graph of relative AP-ssRNA incision by WT APE1 under various Mg2+ concentrations. 1.5 nM WT APE1 was incubated with 200 fmol 5′-γ-32P-radiolabeled 34FRNA in buffer containing the designated Mg2+ concentration at 37°C for 5 min. Average values with standard deviations of at least 3 independent experiments are plotted relative to 1 mM Mg2+.

We next examined the effects of differential Mg2+ concentrations on ssDNA and ssRNA AP site incision activites of WT APE1. Consistent with previous results for dsDNA AP site endonuclease activity33, APE1 required Mg2+ to cleave at an AP site in ssDNA. Optimal ssDNA AP endonuclease activity was observed at a concentration of 1 mM Mg2+, with high levels of incision activity present at both 0.5 and 2 mM Mg2+. A marked decrease in ssDNA AP endonuclease activity occurred at Mg2+ concentrations of 5 and 10 mM, while 20 mM Mg2+ completely inhibited APE1 ssDNA AP site cleavage (Fig. 6c). When we examined ssRNA AP site incision by APE1, we found that differential Mg2+ concentrations affected cleavage much less drastically. Similar to the endoribonuclease activity (Fig. 6a), the ssRNA AP site cleavage activity of APE1 was active in the absence of Mg2+; indeed the highest level of ssRNA AP site incision activity was observed at 0 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 6d). High levels of ssRNA AP site cleavage occurred at all tested Mg2+ concentrations (0.5 mM to 20 mM; Fig. 6d), suggesting that the catalytic mechanism of APE1 RNA cleavage differs from that used for AP DNA cleavage and does not require Mg2+.

Discussion

We previously showed that amino acids H309 and E96, critical for the other known nuclease activities of APE129,33,42–44, are also important for endoribonuclease activity of APE1 on c-myc CRD RNA15. This observation suggested that the RNA-cleaving activity of APE1 resides within the same active site as its other nuclease activities. Furthermore, we reported that the RNA-cleaving activity of APE1 was active in the absence of magnesium32, in stark contrast to the abasic DNA endonuclease activity of APE1 where the metal ion is absolutely essential. Such observations prompted us to further investigate possible differences in the mechanism of RNA-cleavage and AP-DNA endonuclease activities of APE1. Moreover, we sought to identify unique RNA incision properties of APE1 which will ultimately allow for studies of this activity in cells. Our results herein reveal that most amino acid residues that are critical for AP-dsDNA incision are also important for the endoribonuclease activity of APE1. We found, however, the following notable distinctions between the endoribonuclease/AP-RNA endonuclease and AP-DNA endonuclease activities of APE1: (i) in contrast to its prominent role in ds or ssDNA AP site endonuclease activity, D283 is not obviously involved in the RNA-cleaving activity of APE1, nor is it required for the AP-ssRNA incision, (ii) unlike what is seen with AP-DNA substrates, Mg2+ is not required for the endoribonuclease or AP-ssRNA endonuclease activities of APE1, and (iii) the RNA-cleaving activity of APE1 requires a 2′-OH in the sugar moiety of the nucleotide 5′ to the phosphodiester cleavage site. This latter finding is consistent with the observation that APE1 endonucleolytically cleaves RNA leaving behind a 3′-PO42− group.

Employing well established methods for assessing various APE1 activities, we examined the contributions of specific amino acid residues to ss and ds AP-DNA incision34,42, RNA cleavage15, and AP-ssRNA incision31. The comparable degree of reduction in activity presumably corresponds to the importance of a given residue in the various nuclease activities of APE1 and suggests the presence of a common active site (Table 1). The most severe reductions in RNA incision activity were observed with the N68A, Y171F, D210N, and H309S mutations (Table 1).

Although there are multiple proposed reaction mechanisms, N68 and D210 have been found to play critical roles in catalyzing AP-DNA incision, possibly with N68 hydrogen bonding to D210 and H309 to establish the optimal active site environment and D210 participating in the generation of a nucleophile21,23. D70A and D308A displayed moderate decreases in AP-dsDNA activity (Fig. 1a), but complete abrogation of RNA incision activity (Fig. 2b). These two residues have been predicted to coordinate metal ions21 during abasic DNA incision and are thought to orient the substrate, stabilize transition state, and facilitate dissociation of the product. Overall, the results indicate that APE1 shares active site residues responsible for participating in the cleavage of AP-DNA, RNA, and AP-RNA. One particular residue for which this statement does not hold true is D283, where AP-site containing dsDNA (Fig. 1a) and ssDNA (Fig. 4a) activities were abolished by mutation to asparagine, while endoribonuclease (Fig. 2b) and AP-ssRNA incision (Fig. 4b) activities remain robust. Considering the role of D283 in the maintenance of the D283-H309 dyad22, our results indicate that this residue coordination is not critical for RNA incision, while it is vital for efficient AP-DNA incision (Figs. 1a and 4b)22. Our finding that the D283N APE1 protein is still capable of cleaving OligoIA substrate (Fig. 5d) provides further support for this notion.

Previously, H309N was shown to have a 2-fold reduction in its affinity for AP-dsDNA39. This is in line with our results which showed diminished RNA binding ability, compared to WT APE1 (Fig. 3c). Such a result indicates that H309 is involved in the RNA-binding process, and mutation at this position leads to a reduced complex formation and subsequently reduced incision activity. Although our results demonstrated that residues N68, E96, Y171, and D210 (Fig. 2) are critical for RNA incision activity, mutation at these residues had no effect on RNA-binding (Fig. 3), suggesting that the involvement of these residues in RNA-cleavage does not entail the RNA binding step. This conclusion is consistent with their predicted importance in the catalytic reaction mechanism of RNA incision.

In addition to H309, the D283N mutation can modulate RNA binding. At low concentrations (lanes 18 and 19, Fig. 3c), D283N appears to display reduced RNA binding. This observation appears to be consistent with a previous report which showed reduced ability of the mutant to bind AP-dsDNA at lower protein concentrations39. In any case, the impaired binding profile of D283 does not appear to be a major determinant in RNA or AP-ssRNA cleavage, as the D283N mutation did not drastically affect either RNA incision activity of APE1.

In summary, our results showed that, apart from D283, amino acid residues that are critical for AP-DNA incision are also important for the endoribonuclease activity of APE1. These residues most likely play key roles in the catalytic reaction steps of RNA incision, because mutation at these positions did not significantly affect RNA binding. Our findings further confirm that the endoribonuclease activity of APE1 shares a common active site with the other nuclease activities; however our results also show that the mechanisms for incising RNA, AP-ssRNA, AP-dsDNA or AP-ssDNA are not entirely identical. Such distinctions, particularly the observations with the D283 mutation, could well be sufficient to provide opportunities to understand the contributions of the endoribonuclease function of APE1 in controlling gene expression in cells.

Materials and Methods

Purification of recombinant proteins

The recombinant APE1 structural mutants (N68A, D70A, Y171F, F266A, D283N, D308A, and H309S), as well as the WT APE1 protein used for comparative studies, were over-expressed in bacteria and purified as described21. Briefly, following ion-exchange chromatography21, APE1 protein fractions were pooled, concentrated by 80% (w/v) ammonium sulfate, and then fractionated on a BioRad BioSil SEC 125-5 gel filtration column (7.8 mm × 300 mm) in 50 mM Na-HEPES (pH 7.5), 5 % glycerol (w/v), 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM DTT. The flow rate was 0.25 ml/minute. Proteins were detected by ultraviolet absorbance at 280 nm. APE1 proteins were dialyzed overnight against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, 20 % glycerol, 1 mM PMSF and 0.1 mM DTT, and stored at −70 °C.

Preparation of radiolabeled nucleic acids

To synthesize human c-myc CRD RNA corresponding to nts 1705–1792 and nts 1705–1886, the plasmid pGEM4Z-myc 1705–1792 and pGEM4Z-myc 1705–1886 were linearized and in vitro transcribed as described15. Oligonucleotides, Oligo IA (5′-CAAGGTAGTrUATCCTTG-3), and dOligo IA (5′-CAAGGTAGTdUATCCTTG-3′), corresponded to the c-myc CRD nts 1742–1757, and were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) Inc. (Coralville, IA). rU and dU indicate ribose and deoxyribose moieties linked to the Uridine bases, respectively. The RNAs were 5′-end radiolabeled with γ-[32P]-ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. For internal labeling, α-[32P]-UTP (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) was used during transcription15. Tetrahydrofuran (abasic site analog, as depicted as F) containing ssDNA and ssRNA oligonucleotides were purchased from IDT Inc., and radiolabeled at the 5′ end using [γ-32P] ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Unincorporated γ-32P ATP was removed by centrifugation through a G-50 min-spin column (GE Healthcare, Quebec). Labeled oligos were run on a 12% native polyacrylamide gel, intact full-length bands excised, and eluted into 25 mM MOPS pH 7.2 by incubation at 4°C overnight.

In vitro assay for abasic double-stranded DNA incision

The established protocol for APE1 abasic dsDNA endonuclease assay was used with minor modifications34. The 18-mer oligonucleotide 5′-GTCACCGTGFTACGACTC-3′ that contains the model analog of an abasic site, tetrahydrofuran (F), was used. This oligonucleotide and its complementary anti-sense strand 5′-GAGTCGTAACACGGTGAC-3′ were synthesized by IDT Inc. The oligonucleotide containing the abasic site was 5′-end radiolabeled with γ-[32P]-ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The reaction was stopped by heating at 95°C for 2 mins followed by hybridization to 7 times molar excess of the anti-sense strand at room temperature for 60 mins and then at 4°C overnight. The abasic dsDNA incision assay contains 15 μl reaction mixture consisting of 80,000 cpm (0.1 pmoles) of abasic DNA, 25 pg (0.7 fmoles) of APE1, 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 m M EDTA, 2 mM MgCl2 and 100 μg/mL bovine serum albumin. The reaction was carried out at 37°C for 3 mins. Thirty μl of loading dye (9 M urea, 0.2% xylene cyanol, 0.2% bromophenol blue) were added to the reaction samples, and then subjected to electrophoresis on 8% polyacrylamide, 7 M urea gel.

AP site incision assay for single-stranded DNA and RNA

Recombinant wild-type (WT) and D283N APE1, were incubated with PAGE purified 5′-32P-labeled abasic single-stranded 34FDNA (5′-CTGCAGCTGATGCGCFGTACGGATCCCCGGGTAC-3′) or 34FRNA (5′-CUGCAGCUGAUGCGCFGUCCGGAUCCCCGGGUAC-3′) at 37°C in 25 mM MOPS, pH 7.2, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 for the specified times (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 min). For reactions examining differential Mg2+ concentration on incision activity, buffers contained 25 mM MOPS, pH 7.2, 100 mM KCl, and 0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 2 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM or 20 mM MgCl2, respectively. These reactions were incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Reactions with 34FDNA contained 15 pM APE1 and reactions with 34FRNA contained 1.5 nM APE1. Reactions were inhibited by the addition of stop buffer (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, 0.5% bromophenol blue, 0.5% xylene cyanol), and then heated at 95°C for 5 min. Reaction products were resolved by 15% polyacrylamide urea denaturing gel electrophoresis, imaged, and quantified using a Typhoon phosphoimager and ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). For 34FRNA, please note that about 20% background is present in all lanes from incubation with reaction mixture and was subtracted from total product formation at all time points for both WT and D283N APE1.

In vitro endoribonuclease assay

The standard 20 μl-reaction mixture used for this assay included 2 mM DTT, 1.0 unit of RNasin, 2 mM magnesium acetate, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 25 nM of 5′-32P -radiolabeled RNA (~ 5 × 104 cpm). Reactions were incubated for 25 min at 37°C unless otherwise indicated. Forty μl of loading dye (9 M urea, 0.2% xylene cyanol, 0.2% bromophenol blue) were added to the reaction samples, and then 10 μl of reaction mixture were subjected to electrophoresis in 8% polyacrylamide, 7 M urea gel. Gels were then dried and subjected to phosphorImaging using a Cyclone PhosphorImager (Perkin-Elmer, Woodbridge, ON).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)-binding buffers (5 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 2.5 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.5 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 5 units RNasin) were prepared on ice prior to each experiment. In order to facilitate RNA denaturation and renaturation, 30 nM of internally–labeled [32P] c-myc CRD RNA nts 1705–1886 was heated to 50°C for 5 min and cooled to room temperature before adding to the EMSA-binding buffer. EMSA-binding buffer containing radiolabeled RNA was then incubated with purified recombinant protein in a 20-μl reaction volume at 35°C for 15 min. A total of 2 μl EMSA loading dye (250 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 0.2% xylene cyanol) was added to each reaction and 10 μl of the EMSA reaction was loaded onto an 8% native polyacrylamide gel and resolved at 25 mA for 2 hrs. Gels were then subjected to phosphorImaging. The EMSA saturation binding experiments were carried out as described above and the dissociation constant (Kd) for APE1 against RNA was determined by fits to the Hill equation (Equation 1), where Kd is the dissociation constant, [L] is the concentration of APE1 (in nM) and n is the Hill coefficient.

| [Equation 1] |

All saturation binding data was analyzed by densitometry of the autoradiograph using Optiquant software (Perkin Elmer, Woodbridge, ON). For each reaction (an individual lane), the total activity was determined by summing the total counts in bound complexes with the total counts present in the unbound fraction. In lane with no protein added (lane 1 in Fig. 1a), the total activity was determined by drawing a square box around the unbound fraction. The total counts in unbound fractions in lanes with proteins (lanes 2–6 in Fig. 1a), were determined by drawing similar size square box at around the similar mobility as in lane 1 on the gel. This analysis allowed for the calculation of the percentage of RNA bound to the protein. Data was fit to Equation 1 and plotted using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Discovery Grant (#227158) from Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council (NSERC) to C.H.L. W-C.K was a recipient of Pacific Century Scholarship, Michael Smith Foundation of Health Research Junior Graduate Scholarship Award, and NSERC Canada Graduate Scholarship. C.U. was a recipient of NSERC Undergraduate Student Research Award. This work was also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIA to D.M.W.III.

Abbreviations used

- AP

apurinic/apyrimidinic

- APE1

apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1

- RNase

ribonuclease

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DNase

deoxyribonuclease

- ds

double-stranded

- ss

single-stranded DNA

References

- 1.Lebreton A, Tomecki R, Dziembowski A, Seraphin B. Endonucleolytic RNA cleavage by a eukaryotic exosome. Nature. 2008;456:993–997. doi: 10.1038/nature07480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilusz J. RNA stability: is it the endo’ the world as we know it? Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:9–10. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomecki R, Dziembowski A. Novel endoribonucleases as central players in various pathways of eukaryotic RNA metabolism. RNA. 2010;16:1692–1724. doi: 10.1261/rna.2237610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li WM, Barnes T, Lee CH. Endoribonucleases – enzymes gaining spotlight in mRNA metabolism. FEBS J. 2010;277:627–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamura T, Sugita M. A conserved DYW domain of the pentatricopeptide repeat protein possesses a novel endoribonuclease activity. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:4163–4168. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laneve P, Gioia U, Ragno R, Altieri F, Di Franco C, Santini T, Arceci M, Bozzoni I, Caffarelli E. The tumor marker human placental protein 11 is an endoribonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34712–34719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805759200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaeffer D, Tsanova B, Barbas A, Reis FP, Dastidar EG, Sanchez-Rotunno M, Arraiano CM, van Hoof A. The exosome contains domains with specific endoribonuclease, exoribonuclease and cytoplasmic mRNA decay activities. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Ye X, Jiang F, Liang C, Chen D, Peng J, Kinch LN, Grishin NV, Liu Q. C3PO, an endoribonuclease that promotes RNAi by facilitating RISC activation. Science. 2009;325:750–753. doi: 10.1126/science.1176325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eberle AB, Lykke-Andersen S, Mühlemann O, Jensen TH. SMG6 promotes endonucleolytic cleavage of nonsense mRNA in human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim WC, Lee CH. The role of mammalian ribonucleases (RNases) in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1796:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemens MJ, Williams BR. Inhibition of cell-free protein synthesis by pppA2′p5′A2′p5′A: a novel oligonucleotide synthesized by interferon-treated L cell extracts. Cell. 1978;13:565–572. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen JB, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Zhan M, Gorospe M, Hassel BA. Ribosomal protein mRNAs are primary targets of regulation in RNase-L-induced senescence. RNA Biol. 2009;6:305–315. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.3.8526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Ahmadi W, Al-Haj L, Al-Mohanna FA, Silverman RH, Khabar KS. RNase L downmodulation of the RNA-binding protein, HuR, and cellular growth. Oncogene. 2009;28:1782–1791. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng Y, Schoenberg DR. c-Src activates endonuclease-mediated mRNA decay. Mol Cell. 2007;25:779–787. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes T, Kim WC, Mantha A, Kim SE, Izumi T, Sankar M, Lee CH. Identification of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APE1) as the endoribonuclease that cleaves c-myc mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3946–3958. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tell G, Damante G, Caldwell D, Kelley MR. The intracellular localization of APE1/Ref-1: more than a passive phenomenon? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:367–384. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xanthoudakis S, Miao GG, Curran T. The redox and DNA-repair activities of Ref-1 are encoded by nonoverlapping domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:23–27. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mol CD, Izumi T, Mitra S, Tainer JA. DNA-bound structures and mutants reveal abasic DNA binding by APE1 and DNA repair coordination. Nature. 2000;403:451–456. doi: 10.1038/35000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothwell DG, Hickson ID. Asparagine 212 is essential for abasic site recognition by the human DNA repair endonuclease HAP1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4217–4221. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.21.4217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erzberger JP, Barsky D, Schärer OD, Colvin ME, Wilson DM., 3rd Elements in abasic site recognition by the major human and Escherichia coli apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2771–2778. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.11.2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erzberger JP, Wilson DM., 3rd The role of Mg2+ and specific amino acid residues in the catalytic reaction of the major human abasic endonuclease: new insights from EDTA-resistant incision of acyclic abasic site analogs and site-directed mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:447–457. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadi MZ, Coleman MA, Fidelis K, Mohrenweiser HW, Wilson DM., 3rd Functional characterization of APE1 variants identified in the human population. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3871–3879. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.20.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen LH, Barsky D, Erzberger JP, Wilson DM., 3rd Mapping the protein-DNA interface and the metal-binding site of the major human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:447–459. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tell G, Quadrifoglio F, Tiribelli C, Kelley MR. The many functions of APE1/Ref-1: not only a DNA repair enzyme. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11 doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen DS, Herman T, Demple B. Two distinct human DNA diesterases that hydrolyze 3′-blocking deoxyribose fragments from oxidized DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5907–5914. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.21.5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson DM, 3rd, Takeshita M, Grollman AP, Demple B. Incision activity of human apurinic endonuclease (Ape) at abasic site analogs in DNA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16002–16007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suh D, Wilson DM, 3rd, Povirk LF. 3′-phosphodiesterase activity of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease at DNA double-strand break ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2495–2500. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demple B, Harrison L. Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: enzymology and biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:915–948. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barzilay G, Walker LJ, Robson CN, Hickson ID. Site-directed mutagenesis of the human DNA repair enzyme HAP1: identification of residues important for AP endonuclease and RNase H activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1544–1550. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.9.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chou KM, Cheng YC. The exonuclease activity of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APE1). Biochemical properties and inhibition by the natural dinucleotide Gp4G. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18289–18296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212143200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berquist BR, McNeill DR, Wilson DM., III Characterization of abasic endoribonuclease activity of human Ape1 on alternative substrates, as well as effects of ATP and sequence context on AP site incision. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SE, Gorrell A, Rader SD, Lee CH. Endoribonuclease activity of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 revealed by a real-time fluorometric assay. Anal Biochem. 2010;398:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barzilay G, Mol CD, Robson CN, Walker LJ, Cunningham RP, Tainer JA, Hickson ID. Identification of critical active-site residues in the multifunctional human DNA repair enzyme HAP1. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:561–568. doi: 10.1038/nsb0795-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mantha AK, Oezguen N, Bhakat KK, Izumi T, Braun W, Mitra S. Unusual role of a cysteine residue in substrate binding and activity of human AP-endonuclease 1. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sparanese D, Lee CH. CRD-BP shields c-myc and MDR-1 RNA from endonucleolytic attack by a mammalian endoribonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1209–1221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson DM, 3rd, Takeshita M, Demple B. Abasic site binding by the human apurinic endonuclease, Ape, and determination of the DNA contact sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:933–939. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adhikari S, Uren A, Roy R. Dipole-dipole interaction stabilizes the transition state of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-abasic site interaction. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1334–1339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyrkheeva NS, Khodyreva SN, Lavrik OI. Interaction of APE1 and other repair proteins with DNA duplexes imitating intermediates of DNA repair and replication. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2008;73:261–272. doi: 10.1134/s0006297908030048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masuda Y, Bennett RAO, Demple B. Rapid dissociation of human apurinic endonuclease (APE1) from incised DNA induced by magnesium. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30360–30365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lucas JA, Masuda Y, Bennett RA, Strauss NS, Strauss PR. Single-turnover analysis of mutant human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4958–4964. doi: 10.1021/bi982052v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chernokalskaya E, Dompenciel RE, Schoenberg DR. Cleavage properties of an estrogen-regulated polysomal ribonuclease involved in the destabilization of albumin mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:735–742. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson DM., 3rd Properties of and substrate determinants for the exonuclease activity of human apurinic endonuclease APE1. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:1027–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitra S, Izumi T, Boldogh I, Bhakat KK, Chattopadhyay R, Szczesny B. Intracellular trafficking and regulation of mammalian AP-endoribonuclease 1 (APE1), and essential DNA repair protein. DNA Repair. 2007;6:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chou KM, Cheng YC. An exonucleolytic activity of human apurinic /apyrimidinic endonuclease on 3′ mispaired DNA. Nature. 2002;415:655–659. doi: 10.1038/415655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]