Abstract

Ultrasound imaging has gained importance in pulmonary medicine over the last decades including conventional transcutaneous ultrasound (TUS), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS). Mediastinal lymph node staging affects the management of patients with both operable and inoperable lung cancer (e.g., surgery vs. combined chemoradiation therapy). Tissue sampling is often indicated for accurate nodal staging. Recent international lung cancer staging guidelines clearly state that endosonography (EUS and EBUS) should be the initial tissue sampling test over surgical staging. Mediastinal nodes can be sampled from the airways [EBUS combined with transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA)] or the esophagus [EUS fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA)]. EBUS and EUS have a complementary diagnostic yield and in combination virtually all mediastinal lymph nodes can be biopsied. Additionally endosonography has an excellent yield in assessing granulomas in patients suspected of sarcoidosis. The aim of this review, in two integrative parts, is to discuss the current role and future perspectives of all ultrasound techniques available for the evaluation of mediastinal lymphadenopathy and mediastinal staging of lung cancer. A specific emphasis will be on learning mediastinal endosonography. Part I is dealing with an introduction into ultrasound techniques, mediastinal lymph node anatomy and diagnostic reach of ultrasound techniques and part II with the clinical work up of neoplastic and inflammatory mediastinal lymphadenopathy using ultrasound techniques and how to learn mediastinal endosonography.

Keywords: Guidelines, lung cancer, sarcoidosis, staging, endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), endobronchial ultrasound combined with transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA), training, endoscopic ultrasound with bronchoscope fine needle aspiration (EUS-B-FNA), transcutaneous ultrasound (TUS)

Introduction

Tissue acquisition of mediastinal lymph nodes is often essential for diagnostic purposes and in case of malignancy, for accurate staging. Malignant mediastinal lymph node infiltration has a major impact on lung cancer treatment, as those patients without malignant nodal involvement are commonly treated with immediate surgical resection of the tumor containing lobe or received radiotherapy with curative intent whereas those with nodal involvement are treated with chemoradiation (1-6). Chest imaging by computed tomography (CT) including intravenous contrast enhancement provides detailed anatomical information of the mediastinum, hilum, and lung parenchyma and chest wall. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scanning, preferable in combination with CT, can provide important physiological information regarding mediastinal nodes and lesions. Due to limitations of the imaging techniques, enlarged or FDG avid nodes should be sampled to prevent over and under staging.

For a thorough mediastinal nodal evaluation including tissue sampling, a variety of techniques are available: endoscopic techniques (e.g., bronchoscopy), radiological methods [e.g., CT, fluoroscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)], nuclear medicine techniques (e.g., PET) and surgical procedures (e.g., mediastinoscopy and video-assisted thoracoscopy). Additionally ultrasound-derived techniques have been introduced that have changed the workflow in the evaluation of mediastinal diseases. Ultrasound imaging has gained importance including conventional transcutaneous ultrasound (TUS) of the chest wall, and of pleural effusions (7-9). Nowadays, thoracentesis and chest tube placement is preferably performed following prior sonographic evaluation of the chest.

Ultrasound has been established in the head and neck regions to evaluate cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy (10,11). In addition, transcutaneous mediastinal ultrasound (TMUS) is also able to detect normal and pathological lymph nodes in the deeper located mediastinal region but this knowledge is not widespread and requires special skills. Endobronchial ultrasound combined with transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) and endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) have replaced surgical staging as the initial test of choice for mediastinal tissue evaluation (4-6,12-23). Regardless of its numerous advantages, ultrasound-derived techniques are still not utilized to their full potential in respiratory medicine.

The aim of this review in two integrative parts is to discuss the current role and future perspectives of ultrasound techniques for staging of lung cancer and for the evaluation of mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Part I is dealing with an introduction into ultrasound techniques and part II with the mediastinal lymph node anatomy and diagnostic reach of ultrasound techniques, the clinical work up of neoplastic and inflammatory mediastinal lymphadenopathy using ultrasound techniques and how to learn mediastinal endosonography.

Introduction into ultrasound techniques

Non-invasive benchmark: CT, PET-CT, MRI

CT is the anatomical standard for the description of intrapulmonary lesions and mediastinal abnormalities. In the evaluation of mediastinal lymph nodes, the clinical significance of CT is less convincing since CT mainly relies on size parameters. Cut off values for the short-axis diameter of 10-15 mm were suggested to define abnormal lymph nodes for decades (24,25) with false positive and false negative findings in about 25% of cases indicating a low accuracy (26-28). In two systematic analyses the cumulative sensitivity of CT in mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was estimated to be 55% or 61%, respectively, with a specificity of 81% or 79%, respectively (5,29). The lower the cut-off value the higher the sensitivity can be shown at costs of the specificity (30). The problem of metastases in normal sized lymph nodes seen on the CT scan has already been addressed in some earlier studies (31-36). A morphometric study of 2,891 hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes from 256 patients with NSCLC showed a significant difference of diameter between metastatic and non-metastatic lymph nodes. However, 44% of metastatic lymph nodes were <10 mm in diameter, and of 139 patients with no metastatic lymph node involvement as much as 77% had at least one lymph node that was >10 mm in diameter (36). More than one of four patients with NSCLC had metastasis in the second largest but not in the largest mediastinal node (37). Preliminary results of quantitative CT analysis of shape and texture of mediastinal lymph nodes are promising, showing higher sensitivity for the detection of malignant lymph nodes then sole size measurement (38). In short, lymph nodes with a short axis over 10 mm are considered enlarged, but this does not imply malignant involvement.

Results of PET and of integrated PET-CT have improved the accuracy of CT for detecting mediastinal lymph node metastases of NSCLC to some degree. In a recent meta-analysis, the pooled weighted sensitivity and specificity of PET-CT in a patient-based group were estimated 76% and 88%, respectively (39). In a prospective multicenter study the increment of accuracy in detecting lymph node metastasis provided by adding PET to CT was approximately 11% on a per-patient basis (40). Furthermore, integrated PET-CT adds value to staging of lung cancer in the evaluation of chest wall invasion, of mediastinal infiltration, and in the detection of occult distant metastases. However, despite combining functional and morphological imaging in one method, PET-CT is not able to solve the problem of nodal size. Results are disappointing, since false positive findings are relatively frequent in large lymph nodes. In one study the sensitivity of PET-CT was significantly higher among enlarged (>10 mm) than non-enlarged (≤10 mm) lymph nodes (74% vs. 40%). On the other hand, specificity (81% vs. 98%) and accuracy (78% vs. 90%) were significantly lower in enlarged compared to non-enlarged lymph nodes (41). Another study from the same group showed that in NSCLC patients who are clinically staged as N2/N3 negative by integrated PET-CT, 16% will have occult N2 disease following resection. The highest rate of occult (PET-CT negative) N2 involvement was found in the infracarinal (64%) and in the lower paratracheal lymph node stations (28%). As independent predictors of occult N2 disease were identified: centrally located tumors, right upper lobe tumors and [18]FDG-uptake in N1 nodes (42). The risk of false-positive PET-findings in hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes is significantly higher in larger lymph nodes and in lymph nodes with a high volume of macrophages and lymphocytes (43). Moreover, there is a correlation of lymphoid follicular hyperplasia with false-positivity of mediastinal lymph nodes in PET-CT (44), illustrating the risk of misjudging enlarged inflammatory and reactive lymph nodes for lymph node metastases by PET-CT. One recent study found concurrent lung disease or diabetes mellitus, histology other than adenocarcinoma, and a high [18]FDG uptake of the primary tumor to be risk factors of false negative results. On the other hand, age >65 years, good differentiation of the tumor and a low [18]FDGE-uptake of the primary tumor were significantly correlated with false positive results (45).

Therefore, lymph node staging using PET-CT is far from equal to pathological staging. In selected patients with negative PET-CT-results for N2/N3 disease as well as in patients with PET-positive mediastinal lymph nodes, lymph node biopsy is still required for final diagnosis before thoracotomy. In addition to nodal staging, FDG-PET scanning results in the identification of unexpected distant metastasis in up to 5-10% of patients.

Furthermore, it should be mentioned that reimbursement of PET and PET-CT has not been introduced into many health care systems except under a few defined clinical situations (46,47).

The value of MRI in mediastinal imaging is much less compared to the brain, musculoskeletal system, abdomen and pelvis. However, a recent meta-analysis suggested that the accuracy of diffusion-weighted MRI for mediastinal and hilar nodal staging of NSCLC may be comparable to PET-CT (48).

To compare measurements of mediastinal lymph node sizes obtained by CT with those obtained by ultrasound techniques is difficult, because lymph nodes are situated longitudinally in the mediastinum, whereas CT-images are transversally oriented. In contrast, ultrasound allows measurement of lymph node sizes in any plane. Therefore, the sonographically estimated lymph node size correlates closer to the morphometric assessment than to measurements obtained by axial CT (34). Two recent comparative cohort studies found only a weak agreement between thoracic CT and EBUS for size estimation of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes (49,50). Using EBUS-TBNA, malignant cells were obtained from 24% of lymph nodes initially interpreted as normal in size (50).

Invasive benchmarks: mediastinoscopy and video-assisted thoracoscopy

Minimal-invasive surgical methods for mediastinal staging of NSCLC and sampling of mediastinal lymph nodes are standard cervical mediastinoscopy, video-assisted mediastinoscopy (VAM) and lymphadenectomy (VAMLA), and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Access to mediastinal lymph node stations, invasiveness and diagnostic yield differ between the particular surgical methods (Table 1). VAM allows better visualization and has a better lymph node yield (including the opportunity of performing lymph node dissection) than standard mediastinoscopy (5,51). The major limitation of cervical mediastinoscopy is its inability to access lymph node stations 5 and 6. Therefore, several methods are used to supplement cervical mediastinoscopy as the traditional anterior (parasternal) mediastinotomy (Chamberlain procedure), extended cervical mediastinoscopy (ECM) or transcervical extended mediastinoscopy (TEMLA). VATS is generally limited to the evaluation of one side of the mediastinum. It has a major role in diagnosis and treatment of benign and malignant pleural disease as well as of solitary pulmonary nodules of unknown etiology and early stage NSCLC.

Table 1. Yield and safety of surgical methods to access mediastinal and hilar lymph node stations [data from: (5,51-53)].

| Diagnostic yield and safety | Standard mediastinoscopy | VAM/VAMLA | VATS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessible LN stations | 1, 2 R/L, 3, 4 R/L, 7 (anterior) | 1, 2 R/L, 3, 4 R/L, 7 | Right-sided VATS: 3 R, 4 R, 7, 8-10 R; left-sided VATS: 5-7, 8-10 L |

| No access to mediastinal LN stations | 5, 6, 7 (posterior), 8, 9 | 5, 6, 8, 9 | All contralateral stations: right-sided VATS: +5, 6; left-sided VATS: +3, 4 L |

| Diagnostic sensitivity in lung cancer staging | 78% (26 studies, 9,267 patients) | VAM: 89% (7 studies, 995 patients); VAMLA: 94% (2 studies, 386 patients) | 99% (4 studies, 246 patients) |

| Morbidity | 0-5.3% | 0.8-2.9% | 0-9% |

| Mortality | 0-0.08% | 0% | 0% |

VAM, video-assisted mediastinoscopy; VAMLA, video-assisted mediastinoscopy lymphadenectomy; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery; LN, lymph node.

Mediastinal endosonography (endobronchial and transesophageal)

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)

Currently, EBUS can be applied in radial and longitudinal techniques (54-56). Radial miniprobe EBUS (R-EBUS) was first described in 1990 (57,58). It utilizes a rotating mechanical transducer (12 to 30 MHz) at the end of a flexible miniprobe which produces a 360 degrees image perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the catheter. Commonly, the miniprobe is placed through a guide-sheath (8-9 FR) within the working channel of a rigid or flexible bronchoscope. The miniprobe is used to visualize the lesion and to position the guide-sheath which after withdrawal of the miniprobe is used to position instruments for biopsy (e.g., needle, brush, and forceps). R-EBUS is the imaging method with the best detail resolution of the bronchial wall (59) which is of importance for early detection of bronchial carcinoma (60), for differentiating tumor invasion from compression of large airways (61), for assessment of the depth of local tumor infiltration (62,63), and for guidance of endobronchial treatment (photodynamic therapy) in early-stage lung cancer (64). R-EBUS is superior compared to CT in the early T-stages which has been proven in a surgical controlled study. EBUS sensitivity was 89% as compared to CT (25%) and specificity 100% (CT: 80%) (65). R-EBUS may be helpful in the evaluation of unclear stenosis including carcinoma in situ which does not infiltrate lamina propria (66,67). An important application of R-EBUS is biopsy-guidance in peripheral lung lesions (68), in particular of bronchoscopically and fluoroscopically invisible solitary lung nodules (69). A meta-analysis showed a 100% specificity and a 73% sensitivity of R-EBUS-guided biopsy in the diagnosis of peripheral lung cancer (70). The diagnostic yield of R-EBUS-guided biopsy does not exceed CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of solitary lung nodules. However, the major advantage of R-EBUS-guided biopsy over CT-guided biopsy is its superior safety profile, in particular the significantly lower pneumothorax rate (71).

R-EBUS followed by TBNA has also been used for mediastinal lymph node staging of lung cancer (72,73). However, for this indication the longitudinal EBUS (L-EBUS)-technique has prevailed. R-EBUS and L-EBUS are imaging techniques capable of detecting even small mediastinal lymph nodes (66,74,75).

L-EBUS-scopes have been introduced in 2004 (76). They allow ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy (EBUS-TBNA) which is not possible using radial probes (Table 2) (77-80).

Table 2. Established equipment for longitudinal EBUS (77).

| Equipment | Diameter (mm) | Working channel (mm) | Length (mm) | Field of view | Depth penetration (mm) | Frequency (MHz) | Scan modus | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EB1970UK (video EBUS) [Pentax] | 6.9 | 2 | 600 | 100°/45° oblique optic | 0-120 | 5/6.5/7.5/9/10 | Electronic 75° convex array | Compatible with Hitachi Hi-Vision Scanner |

| BF-UC180F (EBUS) [Olympus] | 6.3 | 2.2 | 600 | 80°/135° oblique hybrid optic | 2-50 | 5/6/7.5/10/12 (EU-ME1); 7.5 (EU-C60); 5/7.5/10/12 (Aloka ultrasound systems) | Electronic 50° convex array | Compatible with EU-ME1, EU-C60 and Aloka ultrasound systems |

| EB-530US (video EBUS) [Fujinon] | 6.3 | 2 | 610 | 120°/10° oblique optic | 3-100 | 5/7.5/10/12 | Electronic 60° convex array | Compatible with SU-7000 and SU-8000 |

EBUS, endobronchial ultrasound.

L-EBUS [similar to EUS (81)] can be combined with ultrasound technology including strain imaging techniques [real time elastography (RTE)] (77,82-86) and contrast enhanced Doppler techniques (77). Real-time EBUS-TBNA has been shown to have a higher diagnostic yield in mediastinal staging than blind TBNA and has similar sensitivity to mediastinoscopy (5,87,88).

The examination techniques using radial and linear probes have been described in current textbooks (77). The EBUS technique and the key anatomical landmarks are described in detail later in this review.

Endoscopic (transesophageal) ultrasound (EUS)

Conventional EUS via the transesophageal approach is a minimally invasive diagnostic and also therapeutically valuable technique. EUS also allows the guidance of biopsies to obtain tissue samples from mediastinal lymph nodes and other mediastinal masses but also from centrally located lung tumors and inflammatory diseases including sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. Currently published data have shown that EUS is a valuable technique for the diagnosis of lung cancer and has improved lymph node staging (89). EUS and EBUS allow lymph node biopsy (90-98).

EBUS and EUS: a complimentary approach

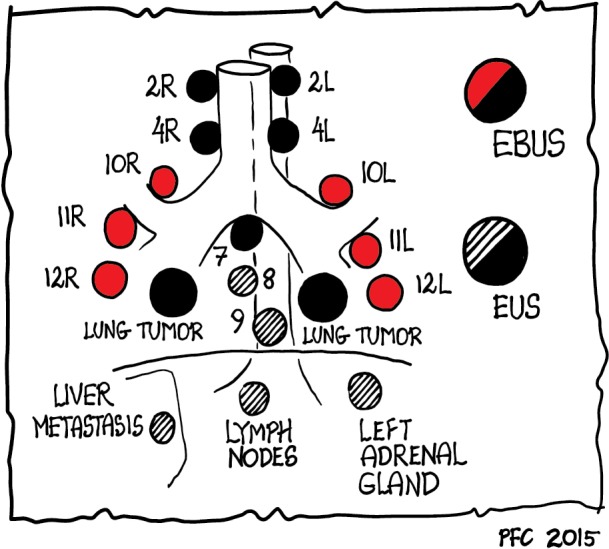

For the evaluation of mediastinal lesions, EBUS and EUS are complimentary methods as various mediastinal and hilar nodal stations can be reached (Figure 1) (99). The added value of EUS to EBUS can be summarized by the complementary diagnostic reach of the lower mediastinum and aorto-pulmonary window in selected cases and the evaluation of the left adrenal gland and other infradiaphragmal metastatic sites [Table 3, data from: (5,16,100-106)].

Figure 1.

Diagnostic reach of mediastinal endosonography (only EBUS: red dots; only EUS: striped dots; EBUS and/or EUS: black dots). EBUS, endobronchial ultrasound; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound.

Table 3. Yield and safety of endosonographic methods (EUS-FNA and EBUS-TBNA) to access mediastinal and hilar lymph node stations [data from: (5,16,100-106)].

| Diagnostic yield and safety | EUS-FNA | EBUS-TBNA | EUS-FNA + EBUS-TBNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessible LN stations | 2 L, (2 Ra), 3 p, 4 L, (4 R), (5b), (6c), 7-9, (10 L/Ra), infradiaphragmatic sites of potential distant metastases (left adrenal, left liver lobe, celiac lymph nodes) | 2 L/R, 3, 4 L/R, 7, 10-11 L/R | 2-4 L/R, (5b), (6c), 7-9, 10-11 L/R |

| No access to mediastinal LN stations | 3a, 11-14 | 5, 6, 8, 9, 12-14 | 12-14 |

| Diagnostic sensitivity | Lung cancer staging: 89% (26 studies, 2,443 patients); mediastinal lymphadenopathy: 88% (32 studies, 2,680 patients) | Lung cancer staging: 89% (26 studies, 2,756 patients); mediastinal lymphadenopathy: 92% (14 studies, 1,658 patients) | Lung cancer staging: 86% (8 studies, 822 patients) |

| Morbidity | 0-2.3% | 0-1.2% | 0-0.8% |

| Mortality | 0% | 0-0.08% | 0% |

a, Only partial access to this station; b, access only in the case of distinctive enlarged lymph nodes; c, access only by transaortic FNA or in semi blind maneuver with a long trajectory through the proximal esophagus along the left subclavian artery. EUS-FNA, endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration; EBUS-TBNA, endobronchial ultrasound combined with transbronchial needle aspiration; LN, lymph node.

EUS is better tolerated by patients compared to EBUS (no coughing or dyspnea). This specifically applies to nodal regions that can be reached by both techniques, the left paratracheal region (station 4 L) and the often affected subcarinal region (station 7). The implementation of endosonographic techniques in lung cancer staging algorithms has also reduced the need for surgical staging options (e.g., mediastinoscopy, thoracoscopy, thoracotomies). However, in the case of suspected nodes by CT/PET imaging and tumor negative findings at EBUS/EUS, additional surgical staging is indicated for optimal nodal staging. This knowledge has gained recognition in recent guidelines (1,2,5,13,107).

Both EUS and EBUS have also been successfully used for the assessment of mediastinal tumor spread of patients with extra-thoracic neoplastic diseases (108-111) and for the evaluation of mediastinal lymphadenopathy of unknown origin and especially for the diagnosis and differentiation of mediastinal granulomatous disease and malignant lymphoma (110,112-124). The examination technique using longitudinal probes has been described in current textbooks (54-56). For a practical approach we refer to the training chapter at the end of this review. The description of currently available equipment including echo-endoscopes and needles and their use has been summarized in detail (77). Pneumological centers are widespread in the USA but less frequent in Europe, e.g., Germany. Therefore, EUS (gastroenterology) and EBUS (pneumology) might be installed in different departments with no or few interactions. The uncoordinated use of EUS and EBUS has been a weakness in the value and clinical work up of ultrasound techniques. The financially and logistically interesting concept consists of a combined endobronchial and esophageal investigation using a single EBUS-echoendoscope where after an initial endobronchial assessment the EBUS scope is subsequently introduced in the esophagus. The results have been promising with a sensitivity of about 90% in staging of NSCLC (17,18). Increasing evidence shows that mediastinal nodal sampling from the esophagus can be performed with the EBUS scope [endoscopic ultrasound with bronchoscope fine needle aspiration (EUS-B-FNA)]. So complete endosonographic staging [EBUS(-TBNA) + EUS-B(-FNA)] can be achieved by a single EBUS scope (17,21,89,125).

An essential part of endosonography is carefully pathology handling. EUS- and EBUS-guided biopsies allow immunostaining in about 80-90% cases which is of importance for subtyping of NSCLC, differential diagnosis to metastases and mesothelioma and for diagnosis of granulomatous diseases and lymphoma [Table 4, data from (1,126-128)].

Table 4. Phenotyping and differential diagnosis of NSCLC and other mediastinal lesions by immunostaining [data from (1,126-128)].

| Tumor type | TTF-1 | CK5/6 | p63 | CK7 | CK20 | Specific markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCLC | + | Keratin, EMA, Ki67 >50% (chromogranin) | ||||

| NSCLC—squamous cell carcinoma | − | + | + | High molecular cytokeratins | ||

| NSCLC—adenocarcinoma | + | + | + | + | − | B72.3, CEA, BerEP4, PAS |

| Metastases of extrathoracic adenocarcinoma | − | − | E.g., CDX2, CEA, CA19-9, PSA, HepPar1, … | |||

| NET | − | − | + | Chromogranin, synaptophysin | ||

| Mesothelioma | − | + | Calretinin, WT-1 | |||

| Lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | LCA (CD45), CD3, CD5; CD10, CD15, CD19, CD20-23, CD30, Cyclin D1, bcl-2, bcl-6 |

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; NET, neuroendocrine tumor.

Cell block technique and preservation of small core particles for formalin fixation and paraffin embedding have improved the results (129-134). In addition genotyping of adenocarcinoma (molecular staging, e.g., EGFR mutation analysis, EML4-ALK fusion gene), flow-cytometry, FISH analysis and other cytogenetic methods are possible using material obtained by EUS-FNA and EBUS-TBNA from mediastinal lesions (118,126,129,132,135-138). Complete genotyping of lung cancer was possible in a recent RCT in 85.7% of cases using specimens obtained by EBUS-TBNA. Rapid onsite cytopathological evaluation (ROSE) significantly improved the rate of complete genotyping and reduced the need for additional needle passes and repeat invasive procedures aiming at molecular diagnosis (139). A recent guideline of the World Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology describes the acquisition and preparation of endosonographic samples for the diagnosis and molecular testing of suspected lung cancer (140).

Safety of mediastinal endosonography

EBUS and EUS are safe techniques (141,142). One study including 965 sheath-guided R-EBUS for the evaluation of peripheral lung nodules reported a 1.3% overall complication rate with pneumothorax occurring in 0.8% and pulmonary infections in 0.5% of patients (143). A systematic review of 190 studies (n=16,181 patients) found severe adverse events in 0.14% and minor adverse events in 0.22% of patients undergoing mediastinal EUS-FNA or EBUS-TBNA. The most serious adverse events (0.07%) were infections and tended to occur most often in patients with cystic mediastinal lesions and sarcoidosis. Serious adverse events were reported in 0.3% of EUS-FNA and in 0.05% of EBUS-TBNA (142). A nationwide survey in the Netherlands (89 hospitals with estimated 14,075 EUS-FNA and 2,675 EBUS-TBNA) reported seven cases of procedure-related fatalities (0.04%), all occurring in patients of poor performance status [American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification score III/IV], and 25 serious adverse events (0.15%, EUS-FNA: 0.16% and EBUS-TBNA: 0.11%). Again, most adverse events were of infectious origin (144).

Safety issues have been also discussed elsewhere (127,145,146).

Transcutaneous mediastinal ultrasound (TMUS)

In addition to the head and neck regions (cervical and supraclavicular nodes), mediastinal ultrasound is also able to detect and to guide sampling of pathological lymph nodes (147,148) and neoplasia (149) in the supra-aortal, prevascular, pericardial, upper and lower located paratracheal region as well as in the aorto-pulmonary window. Studies on mediastinal ultrasound published 20 years ago demonstrated that the suprasternal and parasternal approach, when compared with CT, had a sensitivity of 69-100% for the detection of pathological lymph nodes in the mentioned mediastinal regions (147-150). TMUS is decisive in the supra-aortal, supraclavicular and head and neck regions indicating N3-respective M1-staging (151).

Mediastinal ultrasound is much less often applied and in most centers rarely used in daily routine. Therefore, the value of TMUS is still controversially discussed. The examination technique has been explained and summarized in review articles (152-155) and in respective textbooks (145,156,157).

Definition of mediastinal regions using TMUS

Definitions for lymph node evaluation are similar to CT, EUS and EBUS-criteria. Required criteria for adequate visualization of the different regions are listed in Table 5.

Table 5. Transcutaneous ultrasound (TUS) access to different mediastinal regions. Required adequate visualization of anatomic structures.

| Region | Required adequate visualization of anatomic structures |

|---|---|

| Supraortic | Whole aortic arch with all branches and both brachiocephalic veins (suprasternal approach) |

| Paratracheal | Right brachiocephalic vein, brachiocephalic trunk and ascending aorta, right pulmonary artery (suprasternal approach) |

| Aorto-pulmonary | Whole aortic arch, pulmonary trunk (suprasternal approach) |

| Prevascular | Ascending aorta and pulmonary artery (right and left parasternal approach) |

| Subcarinal | Ascending aorta, right pulmonary artery, left atrium in two planes (right and left parasternal approach) |

| Pericardial | Right atrium, right and left ventricle, pericardial fat pads bilaterally (right and left parasternal approach) |

Detection of normal lymph nodes

The diagnostic value of ultrasound of mediastinal regions depends on differences in echogenicity between pathological lymph nodes and adjacent tissue. This led to the belief that, in contrast to CT, TMUS was not able to differentiate normal mediastinal lymph nodes from surrounding tissue, mostly due to lack of differences in echogenicity. However, using high resolution ultrasound and color Doppler imaging, lymph nodes are detectable also in healthy subjects. Therefore, it is of importance that normal lymph nodes can be regularly detected in the right paratracheal region and aorto-pulmonary window (158,159). Occasionally normal lymph nodes are also detectable in the subcarinal region. The lower detection rate in the subcarinal region may be a consequence of the deep location of this region within the mediastinum, and also to artifacts caused by heart movements.

Mediastinal ultrasound in human corpses

To confirm that normal lymph nodes could be detected by mediastinal ultrasound, 20 human cadavers (11 male, 9 female, 66.4±10.9 years, range: 45-76 years, all without known diseases affecting mediastinal lymph nodes) were examined before and after autopsy to validate the sonographic findings with histologic examinations (159). Lymph nodes were sonographically detected in 85% of the cadavers in the paratracheal region, and in 90% in the aorto-pulmonary window. The longitudinal diameter of detected lymph nodes in the corpses was 8-22 mm in the paratracheal region and 8-17 mm in the aorto-pulmonary window. The sonographically determined lymph node size correlated well with the morphometric measurements of the macro-pathological specimens. In the paratracheal region, 75% of all lymph nodes identified in situ after thoracotomy were detected sonographically, whereas in the aorto-pulmonary window 91% of all lymph nodes identified after thoracotomy were also detected sonographically. All normal lymph nodes were oval in shape. No round lymph node was found. In 21% a lymph node sinus could be identified. Histologic examination revealed lymphatic tissue in all sonographically detected lymph nodes (Table 6) (158,159).

Table 6. Lymph nodes in the mediastinum detected by ultrasound in 20 human cadavers (158,159).

| Mediastinal region | Proportion of cadavers with detectable lymph nodes | Number of lymph nodes (detected by ultrasound)* | Lymph node size (determined by ultrasound) (mm)# | Lymph node size (morphometric measurement) (mm)# |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paratracheal | 17/20 | 1.9±1.0 | 11×6 | 11×6 |

| Aorto-pulmonary window | 18/20 | 1.7±0.7 | 11×5 | 11×4 |

*, The number of lymph nodes is given as mean ± standard deviation; #, the lymph node size is given as the mean longitudinal diameter × mean transversal diameter.

Mediastinal ultrasound in healthy subjects

In the paratracheal region lymph nodes were detected sonographically in 35% of the healthy subjects, in the aorto-pulmonary window in 45% of the cases and in the subcarinal region in 12.5%. All detected lymph nodes had a hypoechogenic appearance. In contrast, in the supra-aortic, the prevascular and the pericardial regions of the healthy subjects lymph nodes >6 mm were not detected by mediastinal ultrasound (159). This finding is in accordance to the literature (160). In the healthy subjects the longitudinal diameter of detected lymph nodes was 10-19 mm in the paratracheal region and 12-19 mm in the aorto-pulmonary window. Due to its typical location and shape, in the aorto-pulmonary window the superior pericardial recessus always could be differentiated from lymph nodes (159,161).

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Goeckenjan G, Sitter H, Thomas M, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, therapy, and follow-up of lung cancer. Interdisciplinary guideline of the German Respiratory Society and the German Cancer Society--abridged version. Pneumologie 2011;65:e51-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felip E, Garrido P, Trigo JM, et al. SEOM guidelines for the management of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Clin Transl Oncol 2009;11:284-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Detterbeck FC, Jantz MA, Wallace M, et al. Invasive mediastinal staging of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest 2007;132:202S-220S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Detterbeck FC, Postmus PE, Tanoue LT. The stage classification of lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e191S-210S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silvestri GA, Gonzalez AV, Jantz MA, et al. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e211S-50S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Leyn P, Dooms C, Kuzdzal J, et al. Revised ESTS guidelines for preoperative mediastinal lymph node staging for non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:787-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koenig SJ, Narasimhan M, Mayo PH. Thoracic ultrasonography for the pulmonary specialist. Chest 2011;140:1332-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koegelenberg CF, von Groote-Bidlingmaier F, Bollinger CT. Transthoracic ultrasonography for the respiratory physician. Respiration 2012;84:337-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietrich CF, Mathis G, Cui XW, et al. Ultrasound of the Pleurae and Lungs. Ultrasound Med Biol 2015;41:351-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui XW, Jenssen C, Saftoiu A, et al. New ultrasound techniques for lymph node evaluation. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:4850-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui XW, Hocke M, Jenssen C, et al. Conventional ultrasound for lymph node evaluation, update 2013. Z Gastroenterol 2014;52:212-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vansteenkiste J, De Ruysscher D, Eberhardt WE, et al. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi89-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilmann P, Clementsen PF, Colella S, et al. Combined endobronchial and esophageal endosonography for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline, in cooperation with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Endoscopy 2015;47:545-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberman M, Sampalis J, Duranceau A, et al. Endosonographic mediastinal lymph node staging of lung cancer. Chest 2014;146:389-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace MB, Pascual JM, Raimondo M, et al. Minimally invasive endoscopic staging of suspected lung cancer. JAMA 2008;299:540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annema JT, van Meerbeeck JP, Rintoul RC, et al. Mediastinoscopy vs endosonography for mediastinal nodal staging of lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 2010;304:2245-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herth FJ, Krasnik M, Kahn N, et al. Combined endoscopic-endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes through a single bronchoscope in 150 patients with suspected lung cancer. Chest 2010;138:790-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwangbo B, Lee GK, Lee HS, et al. Transbronchial and transesophageal fine-needle aspiration using an ultrasound bronchoscope in mediastinal staging of potentially operable lung cancer. Chest 2010;138:795-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szlubowski A, Zielinski M, Soja J, et al. A combined approach of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided needle aspiration in the radiologically normal mediastinum in non-small-cell lung cancer staging--a prospective trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:1175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohnishi R, Yasuda I, Kato T, et al. Combined endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for mediastinal nodal staging of lung cancer. Endoscopy 2011;43:1082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang HJ, Hwangbo B, Lee GK, et al. EBUS-centred versus EUS-centred mediastinal staging in lung cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2014;69:261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KJ, Suh GY, Chung MP, et al. Combined endobronchial and transesophageal approach of an ultrasound bronchoscope for mediastinal staging of lung cancer. PLoS One 2014;9:e91893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oki M, Saka H, Ando M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: Are two better than one in mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:1169-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glazer GM, Gross BH, Quint LE, et al. Normal mediastinal lymph nodes: number and size according to American Thoracic Society mapping. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1985;144:261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quint LE, Glazer GM, Orringer MB, et al. Mediastinal lymph node detection and sizing at CT and autopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;147:469-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gdeedo A, Van Schil P, Corthouts B, et al. Prospective evaluation of computed tomography and mediastinoscopy in mediastinal lymph node staging. Eur Respir J 1997;10:1547-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillemans B, Deneffe G, Verschakelen J, et al. Value of computed tomography and mediastinoscopy in preoperative evaluation of mediastinal nodes in non-small cell lung cancer. A study of 569 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1994;8:37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gdeedo A, Van Schil P, Corthouts B, et al. Comparison of imaging TNM [(i)TNM] and pathological TNM [pTNM] in staging of bronchogenic carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997;12:224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gould MK, Kuschner WG, Rydzak CE, et al. Test performance of positron emission tomography and computed tomography for mediastinal staging in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:879-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dales RE, Stark RM, Raman S. Computed tomography to stage lung cancer. Approaching a controversy using meta-analysis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;141:1096-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arita T, Kuramitsu T, Kawamura M, et al. Bronchogenic carcinoma: incidence of metastases to normal sized lymph nodes. Thorax 1995;50:1267-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKenna RJ, Jr, Libshitz HI, Mountain CE, et al. Roentgenographic evaluation of mediastinal nodes for preoperative assessment in lung cancer. Chest 1985;88:206-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staples CA, Muller NL, Miller RR, et al. Mediastinal nodes in bronchogenic carcinoma: comparison between CT and mediastinoscopy. Radiology 1988;167:367-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arita T, Matsumoto T, Kuramitsu T, et al. Is it possible to differentiate malignant mediastinal nodes from benign nodes by size? Reevaluation by CT, transesophageal echocardiography, and nodal specimen. Chest 1996;110:1004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerr KM, Lamb D, Wathen CG, et al. Pathological assessment of mediastinal lymph nodes in lung cancer: implications for non-invasive mediastinal staging. Thorax 1992;47:337-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prenzel KL, Monig SP, Sinning JM, et al. Lymph node size and metastatic infiltration in non-small cell lung cancer. Chest 2003;123:463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikeda K, Nomori H, Mori T, et al. Size of metastatic and nonmetastatic mediastinal lymph nodes in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2006;1:949-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bayanati H, E Thornhill R, Souza CA, et al. Quantitative CT texture and shape analysis: can it differentiate benign and malignant mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with primary lung cancer? Eur Radiol 2015;25:480-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lv YL, Yuan DM, Wang K, et al. Diagnostic performance of integrated positron emission tomography/computed tomography for mediastinal lymph node staging in non-small cell lung cancer: a bivariate systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:1350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kubota K, Murakami K, Inoue T, et al. Additional value of FDG-PET to contrast enhanced-computed tomography (CT) for the diagnosis of mediastinal lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer: a Japanese multicenter clinical study. Ann Nucl Med 2011;25:777-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Sarraf N, Gately K, Lucey J, et al. Lymph node staging by means of positron emission tomography is less accurate in non-small cell lung cancer patients with enlarged lymph nodes: analysis of 1,145 lymph nodes. Lung Cancer 2008;60:62-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Sarraf N, Aziz R, Gately K, et al. Pattern and predictors of occult mediastinal lymph node involvement in non-small cell lung cancer patients with negative mediastinal uptake on positron emission tomography. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;33:104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shiraki N, Hara M, Ogino H, et al. False-positive and true-negative hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes on FDG-PET--radiological-pathological correlation. Ann Nucl Med 2004;18:23-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung JH, Cho KJ, Lee SS, et al. Overexpression of Glut1 in lymphoid follicles correlates with false-positive (18)F-FDG PET results in lung cancer staging. J Nucl Med 2004;45:999-1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li S, Zheng Q, Ma Y, et al. Implications of false negative and false positive diagnosis in lymph node staging of NSCLC by means of (1)(8)F-FDG PET/CT. PLoS One 2013;8:e78552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dietrich CF, Riemer-Hommel P. Challenges for the German Health Care System. Z Gastroenterol 2012;50:557-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dietrich CF. Editorial on the contribution "Challenges for the German Health Care System". Z Gastroenterol 2012;50:555-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu LM, Xu JR, Gu HY, et al. Preoperative mediastinal and hilar nodal staging with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: which is better? J Surg Res 2012;178:304-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dhooria S, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, et al. Agreement of Mediastinal Lymph Node Size Between Computed Tomography and Endobronchial Ultrasonography: A Study of 617 Patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:1894-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Udoji TN, Phillips GS, Berkowitz EA, et al. Mediastinal and Hilar Lymph Node Measurements. Comparison of Multidetector-Row Computed Tomography and Endobronchial Ultrasound. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:914-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adebibe M, Jarral OA, Shipolini AR, et al. Does video-assisted mediastinoscopy have a better lymph node yield and safety profile than conventional mediastinoscopy? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;14:316-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schipper P, Schoolfield M. Minimally invasive staging of N2 disease: endobronchial ultrasound/transesophageal endoscopic ultrasound, mediastinoscopy, and thoracoscopy. Thorac Surg Clin 2008;18:363-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zakkar M, Tan C, Hunt I. Is video mediastinoscopy a safer and more effective procedure than conventional mediastinoscopy? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;14:81-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dietrich CF, Nuernberg D. Lehratlas der interventionellen Sonographie. Thieme Verlag, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dietrich CF. Endosonographie. Lehrbuch und Atlas des endoskopischen Ultraschalls. Thieme Verlag, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dietrich CF. Endoscopic ultrasound, an introductory manual and atlas. Second edition. Thieme Verlag, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hürter T, Hanrath P. Endobronchial sonography in the diagnosis of pulmonary and mediastinal tumors. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1990;115:1899-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hürter T, Hanrath P. Endobronchial sonography: feasibility and preliminary results. Thorax 1992;47:565-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baba M, Sekine Y, Suzuki M, et al. Correlation between endobronchial ultrasonography (EBUS) images and histologic findings in normal and tumor-invaded bronchial wall. Lung Cancer 2002;35:65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herth FJ. Playing with the wavelengths: endoscopic early lung cancer detection. Lung Cancer 2010;69:131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herth F, Ernst A, Schulz M, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound reliably differentiates between airway infiltration and compression by tumor. Chest 2003;123:458-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurimoto N, Murayama M, Yoshioka S, et al. Assessment of usefulness of endobronchial ultrasonography in determination of depth of tracheobronchial tumor invasion. Chest 1999;115:1500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanaka F, Muro K, Yamasaki S, et al. Evaluation of tracheo-bronchial wall invasion using transbronchial ultrasonography (TBUS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000;17:570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miyazu Y, Miyazawa T, Kurimoto N, et al. Endobronchial ultrasonography in the assessment of centrally located early-stage lung cancer before photodynamic therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takemoto Y, Kawahara M, Ogawara M, et al. Ultrasound-guided flexible bronchoscopy for the diagnosis of tumor invasion to the bronchial wall and mediastinum. J Bronchol 2000;7:127-32. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Herth FJ. Bronchoscopy/Endobronchial ultrasound. Front Radiat Ther Oncol 2010;42:55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gompelmann D, Eberhardt R, Herth FJ. Endobronchial ultrasound. Radiologe 2010;50:692-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herth FJ, Krasnik M, Vilmann P. EBUS-TBNA for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Endoscopy 2006;38:S101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herth FJ, Eberhardt R, Becker HD, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial lung biopsy in fluoroscopically invisible solitary pulmonary nodules: a prospective trial. Chest 2006;129:147-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steinfort DP, Khor YH, Manser RL, et al. Radial probe endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis of peripheral lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2011;37:902-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steinfort DP, Vincent J, Heinze S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of radial probe endobronchial ultrasound versus CT-guided needle biopsy for evaluation of peripheral pulmonary lesions: a randomized pragmatic trial. Respir Med 2011;105:1704-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Okamoto H, Watanabe K, Nagatomo A, et al. Endobronchial ultrasonography for mediastinal and hilar lymph node metastases of lung cancer. Chest 2002;121:1498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Plat G, Pierard P, Haller A, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound and positron emission tomography positive mediastinal lymph nodes. Eur Respir J 2006;27:276-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gomez M, Silvestri GA. Endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009;6:180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yasufuku K, Nakajima T, Fujiwara T, et al. Role of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in the management of lung cancer. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;56:268-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yasufuku K, Chhajed PN, Sekine Y, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound using a new convex probe: a preliminary study on surgically resected specimens. Oncol Rep 2004;11:293-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dietrich CF. Endobronchialer Ultraschall (EBUS). In: Dietrich CF, Nurnberg D, editors. Interventionelle Sonographie. Thieme Verlag, 2011:387-99. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yasufuku K, Chiyo M, Sekine Y, et al. Real-time endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Chest 2004;126:122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Colella S, Vilmann P, Konge L, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Endosc Ultrasound 2014;3:205-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gompelmann D, Eberhardt R, Herth FJ. Endobronchial ultrasound. Endosc Ultrasound 2012;1:69-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Janssen J, Dietrich CF, Will U, et al. Endosonographic elastography in the diagnosis of mediastinal lymph nodes. Endoscopy 2007;39:952-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dietrich CF. Echtzeit-Gewebeelastographie. Anwendungsmöglichkeiten nicht nur im Gastrointestinaltrakt. Endoskopie Heute 2010;23:177-212. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bamber J, Cosgrove D, Dietrich CF, et al. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 1: Basic principles and technology. Ultraschall Med 2013;34:169-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cosgrove D, Piscaglia F, Bamber J, et al. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 2: Clinical applications. Ultraschall Med 2013;34:238-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Izumo T, Sasada S, Chavez C, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound elastography in the diagnosis of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2014;44:956-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Okasha HH, Mansour M, Attia KA, et al. Role of high resolution ultrasound/endosonography and elastography in predicting lymph node malignancy. Endosc Ultrasound 2014;3:58-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kheir F, Palomino J. Endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration in mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathies. South Med J 2012;105:645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ge X, Guan W, Han F, et al. Comparison of Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration and Video-Assisted Mediastinoscopy for Mediastinal Staging of Lung Cancer. Lung 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Annema JT. Complete endosonographic staging of lung cancer. Thorax 2014;69:675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dincer HE, Gliksberg EP, Andrade RS. Endoscopic ultrasound and/or endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of central intraparenchymal lung lesions not adjacent to airways or esophagus. Endosc Ultrasound 2015;4:40-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fuccio L, Larghi A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: How to obtain a core biopsy? Endosc Ultrasound 2014;3:71-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harris K, Maroun R, Attwood K, et al. Comparison of cytologic accuracy of endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration using needle suction versus no suction. Endosc Ultrasound 2015;4:115-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hébert-Magee S. Basic technique for solid lesions: Cytology, core, or both? Endosc Ultrasound 2014;3:28-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lachter J. Basic technique in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for solid lesions: What needle is the best? Endosc Ultrasound 2014;3:46-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Paquin SC. Training in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Endosc Ultrasound 2014;3:12-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sahai AV. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration studies: Fanning the flames. Endosc Ultrasound 2014;3:68-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sahai AV. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration: Getting to the point. Endosc Ultrasound 2014;3:1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wani S. Basic techniques in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration: Role of a stylet and suction. Endosc Ultrasound 2014;3:17-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vilmann P, Krasnik M, Larsen SS, et al. Transesophageal endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) biopsy: a combined approach in the evaluation of mediastinal lesions. Endoscopy 2005;37:833-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Asano F, Aoe M, Ohsaki Y, et al. Complications associated with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a nationwide survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy. Respir Res 2013;14:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gu P, Zhao YZ, Jiang LY, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for staging of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1389-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Puli SR, Batapati Krishna RJ, Bechtold ML, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound: it's accuracy in evaluating mediastinal lymphadenopathy? A meta-analysis and systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:3028-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Eapen GA, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. Complications, consequences, and practice patterns of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: Results of the AQuIRE registry. Chest 2013;143:1044-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chandra S, Nehra M, Agarwal D, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy in mediastinal lymphadenopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Care 2012;57:384-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Varela-Lema L, Fernandez-Villar A, Ruano-Ravina A. Effectiveness and safety of endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2009;33:1156-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang R, Ying K, Shi L, et al. Combined endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for mediastinal lymph node staging of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1860-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tournoy KG, Keller SM, Annema JT. Mediastinal staging of lung cancer: novel concepts. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Peric R, Schuurbiers OC, Veselic M, et al. Transesophageal endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for the mediastinal staging of extrathoracic tumors: a new perspective. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1468-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tournoy KG, Govaerts E, Malfait T, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy for M1 staging of extrathoracic malignancies. Ann Oncol 2011;22:127-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Navani N, Nankivell M, Woolhouse I, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for the diagnosis of intrathoracic lymphadenopathy in patients with extrathoracic malignancy: a multicenter study. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:1505-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sanz-Santos J, Cirauqui B, Sanchez E, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of intrathoracic lymph node metastases from extrathoracic malignancies. Clin Exp Metastasis 2013;30:521-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fritscher-Ravens A, Sriram PV, Bobrowski C, et al. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in patients with or without previous malignancy: EUS-FNA-based differential cytodiagnosis in 153 patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:2278-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fritscher-Ravens A, Ghanbari A, Topalidis T, et al. Granulomatous mediastinal adenopathy: can endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration differentiate between tuberculosis and sarcoidosis? Endoscopy 2011;43:955-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Puri R, Vilmann P, Sud R, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology in the evaluation of suspected tuberculosis in patients with isolated mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Endoscopy 2010;42:462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sun J, Teng J, Yang H, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in diagnosing intrathoracic tuberculosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:2021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.von Bartheld MB, Dekkers OM, Szlubowski A, et al. Endosonography vs conventional bronchoscopy for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis: the GRANULOMA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309:2457-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, et al. Prospective study of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of lymph nodes versus transbronchial lung biopsy of lung tissue for diagnosis of sarcoidosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;143:1324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yasuda I, Goto N, Tsurumi H, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy for diagnosis of lymphoproliferative disorders: feasibility of immunohistological, flow cytometric, and cytogenetic assessments. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.von Bartheld MB, Veselic-Charvat M, Rabe KF, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Endoscopy 2010;42:213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Agarwal R, Srinivasan A, Aggarwal AN, et al. Efficacy and safety of convex probe EBUS-TBNA in sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med 2012;106:883-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Navani N, Molyneaux PL, Breen RA, et al. Utility of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in patients with tuberculousintrathoracic lymphadenopathy: a multicentre study. Thorax 2011;66:889-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mehmood S, Loya A, Yusuf MA. Clinical utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of mediastinal and intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy. Acta Cytol 2013;57:436-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Moonim MT, Breen R, Fields PA, et al. Diagnosis and subtyping of de novo and relapsed mediastinal lymphomas by endobronchial ultrasound needle aspiration. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:1216-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nunez AL, Jhala NC, Carroll AJ, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound and endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of deep-seated lymphadenopathy: Analysis of 1338 cases. Cytojournal 2012;9:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hwangbo B, Kim SK, Lee HS, et al. Application of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration following integrated PET/CT in mediastinal staging of potentially operable non-small cell lung cancer. Chest 2009;135:1280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kerr KM. Personalized medicine for lung cancer: new challenges for pathology. Histopathology 2012;60:531-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Jenssen C, Dietrich CF. Kontraindikationen, Komplikationen, Komplikationsmanagment. In: Dietrich CF, Nurnberg D, editors. Interventionelle Sonographie. Thieme Verlag 2011:127-60. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jenssen C, BT. Feinnadel-Aspirations-Zytologie. In: Dietrich C, ND, editors. Lehratlas der interventionellen Sonographie. Thieme Verlag, 2011:76-98. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Navani N, Brown JM, Nankivell M, et al. Suitability of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration specimens for subtyping and genotyping of non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter study of 774 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:1316-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tournoy KG, Carprieaux M, Deschepper E, et al. Are EUS-FNA and EBUS-TBNA specimens reliable for subtyping non-small cell lung cancer? Lung Cancer 2012;76:46-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Savic S, Bihl MP, Bubendorf L. Non-small cell lung cancer. Subtyping and predictive molecular marker investigations in cytology. Pathologe 2012;33:301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Esterbrook G, Anathhanam S, Plant PK. Adequacy of endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration samples in the subtyping of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2013;80:30-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kossakowski CA, Morresi-Hauf A, Schnabel PA, et al. Preparation of cell blocks for lung cancer diagnosis and prediction: protocol and experience of a high-volume center. Respiration 2014;87:432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wallace WA, Rassl DM. Accuracy of cell typing in nonsmall cell lung cancer by EBUS/EUS-FNA cytological samples. Eur Respir J 2011;38:911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ulivi P, Romagnoli M, Chiadini E, et al. Assessment of EGFR and K-ras mutations in fixed and fresh specimens from transesophageal ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Int J Oncol 2012;41:147-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Araya T, Demura Y, Kasahara K, et al. Usefulness of transesophagealbronchoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in the pathologic and molecular diagnosis of lung cancer lesions adjacent to the esophagus. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2013;20:121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sakairi Y, Nakajima T, Yasufuku K, et al. EML4-ALK fusion gene assessment using metastatic lymph node samples obtained by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:4938-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Santis G, Angell R, Nickless G, et al. Screening for EGFR and KRAS mutations in endobronchial ultrasound derived transbronchial needle aspirates in non-small cell lung cancer using COLD-PCR. PLoS One 2011;6:e25191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Trisolini R, Cancellieri A, Tinelli C, et al. Randomized trial of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration with and without rapid on-site evaluation for lung cancer genotyping. Chest 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.van der Heijden EH, Casal RF, Trisolini R, et al. Guideline for the acquisition and preparation of conventional and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration specimens for the diagnosis and molecular testing of patients with known or suspected lung cancer. Respiration 2014;88:500-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Jenssen C, Alvarez-Sanchez MV, Napoleon B, et al. Diagnostic endoscopic ultrasonography: assessment of safety and prevention of complications. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:4659-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.von Bartheld MB, van Breda A, Annema JT. Complication rate of endosonography (endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound): a systematic review. Respiration 2014;87:343-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Hayama M, Izumo T, Matsumoto Y, et al. Complications with Endobronchial Ultrasound with a Guide Sheath for the Diagnosis of Peripheral Pulmonary Lesions. Respiration 2015;90:129-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.von Bartheld MB, Annema JT. Endosonography-related mortality and morbidity for pulmonary indications: a nationwide survey in the Netherlands. Gastrointest Endosc 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Jenssen C, Gottschalk U, Schachschal G, et al. KursbuchEndosonografie. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Jenssen C, Moeller K, Sarbia M, et al. EUS-Guided Biopsy—Indications, Problems, Pitfalls, Troubleshooting, and Clinical Impact. In: Dietrich CF, editor. Endoscopic Ultrasound: An Introductory Manual and Atlas. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Wernecke K, Peters PE, Galanski M. Mediastinal tumors: evaluation with suprasternal sonography. Radiology 1986;159:405-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Wernecke K, Vassallo P, Potter R, et al. Mediastinal tumors: sensitivity of detection with sonography compared with CT and radiography. Radiology 1990;175:137-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wernecke K, Vassallo P, Rutsch F, et al. Thymic involvement in Hodgkin disease: CT and sonographic findings. Radiology 1991;181:375-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Wernecke K, Potter R, Peters PE, et al. Parasternal mediastinal sonography: sensitivity in the detection of anterior mediastinal and subcarinal tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1988;150:1021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Prosch H, Strasser G, Sonka C, et al. Cervical ultrasound (US) and US-guided lymph node biopsy as a routine procedure for staging of lung cancer. Ultraschall Med 2007;28:598-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Wernecke K, Diederich S. Sonographic features of mediastinal tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;163:1357-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Wernecke K. The examination technic and indications for mediastinal sonography. Rofo 1989;150:501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Dietrich CF, Hirche TO, Schreiber D, et al. Sonographie von pleura und lunge. Ultraschall Med 2003;24:303-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Hirche TO, Wagner TO, Dietrich CF. Mediastinal ultrasound: technique and possible applications. Med Klin (Munich) 2002;97:472-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Dietrich CF. Ultraschall-Kurs. 6. Auflage. DeutscherÄrzteverlag, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Dietrich CF, Hocke M. Mediastinum. In: Dietrich CF, editor. Endosonographie. Georg Thieme Verlag 2008:422-32. [Google Scholar]

- 158.Dietrich CF, Liesen M, Wehrmann T, et al. Mediastinalsonographie: Eine neue Bewertung der Befunde. Ultraschall Med 1995;16:61. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Dietrich CF, Liesen M, Buhl R, et al. Detection of normal mediastinal lymph nodes by ultrasonography. Acta Radiol 1997;38:965-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Genereux GP, Howie JL. Normal mediastinal lymph node size and number: CT and anatomic study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1984;142:1095-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Alraiyes AH, Almeida FA, Mehta AC. Pericardial recess through the eyes of endobronchial ultrasound. Endosc Ultrasound 2015;4:162-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]