Abstract

Background:

Pregnancy can be in conflict with sexual function which can be affected by physical and psychological changes during pregnancy. Therefore, comparison of the effect of face-to-face education with group education on sexual function during pregnancy in couples was the purpose of this research.

Materials and Methods:

In this quasi-experimental pre-test post-test study, 64 pregnant couples were selected and randomized in two groups in Isfahan. The data were collected using the triangulation of Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), Brief form of Sexual Function Inventory (BSFI), and demographic characteristics questionnaires. The data were analyzed by independent t-test, paired t-test, Chi-square, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), and analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS.

Results:

No significant difference was found in the demographic characteristics between the two groups. Education was effective on sexual function in the two groups of women (P < 0.001), but no significant difference was found between the two groups (P = 0.61). Also, education was effective on sexual function of men in both the groups (P < 0.001) and there was a significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.003). Meanwhile, there was no significant difference between couples regarding the education (P = 0.104).

Conclusions:

The results of the study showed that type of education plays a role in improvement of sexual function in pregnancy. In addition, sex education is effective in prevention of sexual disorders in pregnancy. Therefore, having a special approach toward sex education classes during pregnancy is important for the health providers, particularly midwifery professionals.

Keywords: Face-to-face education, group education, Iran, pregnancy, sexual function

INTRODUCTION

A healthy sexual relationship includes an informed and positive tool of sexual energy in the direction of an increase in self-esteem, sexual health, and an emotional relationship and development of personality with a reciprocal benefit for the couples. Marital satisfaction is associated with mental health, general happiness, and successful social interactions and professional outcomes.[1] Meanwhile, several factors affect the sexual relationship. One of these factors, affecting the quality and quantity of sexual relationship, is pregnancy. It is a specific and natural period of a women's life with physical and hormonal, psychological, social, and cultural changes affecting sexual desires, which influences couples’ sexual health.[2] Corbacioqlu et al. found that women had a reduction in their sexual function after knowing about their pregnancy.[3] As sexual relationship is a reciprocal relationship, a change in women's sexual function can affect the fulfillment of men's sexual needs and lead to a disorder in women's sexual function as well as the incidence or increase of sexual disorders among the couples, which can result in notable discrepancies in couples’ marital relationship.[4] Research shows that sexual desire and function is unpredictable during pregnancy among the couples and can decrease, increase, or even remain steady.[5,15] International studies show that sexual disorders’ prevalence is 30–46% among non-pregnant women and reaches 57–75% during pregnancy.[14,18] Physical, emotional, and economic stress during pregnancy often affects couples’ sexual and marital relationship. Sexual ideas and behavior during pregnancy are also under the influence of sexual valuing systems, traditions, and customs (limitations), religious beliefs, physical changes, and exaggerative medical limitations.[19] One of the common questions of couples during pregnancy and in postpartum period is whether sexual relationship is forbidden or not. Such questions help midwives and physicians educate their clients.[12] Therefore, although the sexual desires are instinctive and unintentional, sexual attitudes and behaviors are acquired issues. Lack of information about the changes can lead to conflicts in couples’ sexual relationships and predispose them to sexual disorders, especially during pregnancy in which mental, psychological, and physical changes can result in a change of sexual behaviors.[25] Sex education gives the individuals the needed sexual knowledge and information to set a common goal to fulfill the sexual needs and make a balance in personal, familial, and social life.[20] Fentahun et al. conducted a study in Ethiopia and found a positive attitude for establishment of sex education in schools.[21] Sex education and investigation of abnormal behaviors and detection of the corruption and threats resulting from them have never been socially accepted and are always considered with shyness and as a taboo in Iran. In fact, education is a part of maternal health, which has been less noted in Iranian studies.[22] This is also a process that helps healthy physical growth, marital health, interpersonal relationships, affection, friendship, body image, and sex-based roles. Sex education is associated with cognitive domain (knowledge and information), emotional domain (feeling, values, and attitudes), and behavioral domain (communication skills and decision making).[20] Unfortunately, the health care providers ignore this important aspect of individuals’ life (clients’ sexual desire and satisfaction) and despite having adequate skills in this field, make excuses such as limitation of time, dismay, and disability. They never play their role in detection and evaluation of sexual disorders, although they can be very efficient through explanation of complicated conditions affecting couples’ sexual desire and satisfaction and encouragement of the couples to have a more positive sexual function.[23,25] In most of the developed countries, there are clinics for couples’ sexual problems and they solve familial problems.[25] These centers give services as sex clinics. Their educational content includes human growth (anatomy and physiology of the reproductive system); relationships including relationship with family, friends, and a private marital partner; personal skills including values, decision-making communications and negotiations with others; sexual behavior including all desires and prevention of sexual relationship; sexual health and hygiene including contraception methods, HIV prevention, sexual abuse and venerable diseases; and culture and society including sexuality roles, gender, and religion.[20] Selection of appropriate educational methods to promote clients’ health or changing their incorrect behaviors is among the main educational goals that need investigation and research. There are various educational methods. Designing and application of an educational software is one of them and can be used either for face-to-face or group education. One of the advantages of an educational software is its privacy in education of sensitive issues such as sex education when the individuals feel ashamed, which acts as a facilitating tool in education and learning.[26] In a study conducted by Aibposh et al. in middle schools, the educational software improved students’ knowledge and caused proper healthy behaviors.[27] Kamalifard et al., in a study in Tabriz, showed that an educational software led to improvement of knowledge, attitude, and nutritional behaviors among pregnant women. They recommended that method as an educational method in health care centers.[28] There are several studies in the context of comparing the efficiency of various educational methods including face-to-face and group education. Some have emphasized on face-to-face and some on group (lecture and seminar) education. In some cases, no significant difference has been reported between various methods.[29] Educational programs have shown more effect of personal or face-to-face methods compared to traditional methods.[30] In the study of Boer et al., the concentration on group education through illustrations resulted in a better learning and retention of the materials.[31] In most of developed countries, there are sex education sites, schools, and clinics, which are available to everybody. One of the available and convenient methods for education in Iran is prenatal educational classes held in health care centers to which the pregnant women (and in some cases, their spouses) routinely refer.

Education can be conducted through various methods including personal or face-to-face and group education, which have been selected in the present study. The present study aimed to investigate the effect of face-to-face or group education during the pregnancy period on sexual function of the couples under coverage of selected clinics in Isfahan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a quasi-experimental pre-test post-test two-group study. Sixty-four couples were randomly selected from the pregnant women's files in selected clinics of Isfahan and were assigned to either group or face-to-face educational group (n = 32 in each group). Sampling was conducted from August to November 2013. The couples who were interested to attend the study were given adequate explanations about the classes and the goal and method of the study through telephone calls. After obtained a signed consent form from the subjects and assuring them about the confidentiality of their information, pre-test was conducted either by the researcher through an interview or by the subjects in a private and quiet place which had been considered for this reason. The subjects were asked to answer the questions of a sexual function questionnaire separately before beginning the educational session (men's sexual function questionnaire was filled by men and vice versa). Inclusion criteria were: Iranian nationality, couples being Muslim, gestational age of over 20 weeks, women aged under 40 years and men aged around 50 years, signing a written consent form by the couples to attend the study, no history of medical diseases in couples, no consumption of medication contraindicating with sexual function, no addiction to drugs in any of the couples, no high-risk pregnancy, and not having experienced an acute stressful event during recent years, such as a child's death, spousal treason, acute disease, etc., by any of the couples, which was measured by Holmz Rahe Stress Questionnaire (stress score less than 200). In the face to face education group, each couple were educated through an educational power point file and an educational software in a 90-120 min session. In final, researcher reply to couples’ questions. In the group education group, the subjects were divided into three 10-13 subject groups and the education was conducted similar to face-to-face education group during a 120-min session.

At the end of sessions, educational software and an educational power point, based on related issues, were prepared and given to both groups to let them review the educated items, when needed. Education lasted for 1 month. The subjects attended a post-test 4 weeks after intervention. Education in the direction of sexual health is an accepted issue in our religious instructions and is not in conflict with our health ethics, and this item was considered during the education in the present study.

To collect the data, the demographic characteristics questionnaire, Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), and Brief form of Sexual Function Inventory (BSFI) for males were used. The demographic characteristics questionnaire that was a researcher-made questionnaire contained questions on couple's age, couple's education, length of marriage, and number of pregnancies and children. BSFI is a five-point Likert's scale that contains six sections. Subjects’ score was calculated in each section and through the related index, and ranged 2–36 points. Total score was calculated by summing up the scores for each couple. These questionnaires have been already accredited in Iran. Reliability of the questionnaires was already established by Cronbach's alpha = 0.7 in Iran. The data were analyzed by independent t-test, paired t-test, Chi-square, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), and analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Isfahan University of Medical. An informed consent was taken from all participants.

RESULTS

Mean ages of the subjects and their spouses in group education were 26.1 and 31.5 years, respectively. Most of the women administered group education were homemakers (78.1%) and had high school diploma (50%). About 43.8% of their spouses (most of them) were self-employed and had high school diploma (46.9%). Mean age difference of the couples was 5.4 years, mean length of their marriage was 4.4 years, and mean gestational age of women was 26 weeks. In the face-to-face education group, mean ages of the subjects and their spouses were 26.2 and 30.9 years, respectively. Most of the women were homemakers (81.2%) and had high school diploma (43.8%). Most of their spouses were self-employed (40.6%) and had high school diploma (25%). Mean age difference of the couples was 4.8 years, length of marriage was 4.2 years, and women's gestational age was 27 weeks and 2 days. A high percentage of pregnancies was wanted and planned in both groups (90.6%). Mean, SD, Chi-square, and Mann–Whitney test showed no significant difference in both groups concerning demographic characteristics and the groups were identical concerning the above-mentioned variables.

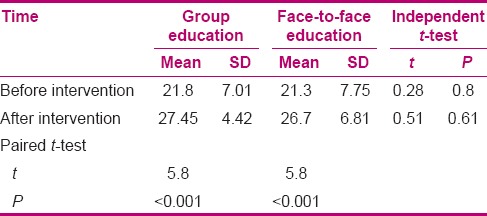

Mean scores of women's sexual function, obtained by FSFI, were compared in the two groups of face-to-face and group education through independent t-test and paired t-test. Paired t-test showed a significant increase in the mean total score of women's sexual function both in face-to-face and group education groups after intervention. Independent t-test showed no significant difference in the mean total score of women's sexual function either before or after intervention between the two groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Mean total scores of women's sexual function in the two groups before and after intervention

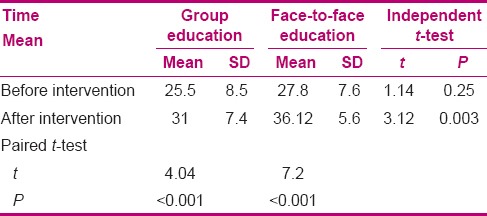

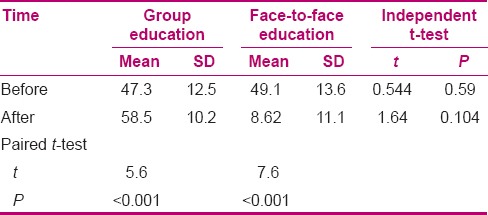

Mean total scores of men's sexual function, obtained by BSFI, were compared in the two groups. Paired t-test showed a significant increase in men's sexual function both in face-to-face and group education groups after intervention. Independent t-test showed no significant difference in mean total scores of sexual function between the two groups before intervention, although the difference was significant after intervention (mean score of men's sexual function was more in face-to-face education group compared to group education group) [Table 2]. Paired t-test showed a significant increase in couples’ mean score of sexual function both in face-to-face and group education groups. Independent t-test showed no significant difference in the mean total score of sexual function either before or after intervention between the two groups [Table 3].

Table 2.

Mean total scores of men's sexual function in the two groups before and after intervention

Table 3.

Mean total scores of couples’ sexual function in the two groups before and after intervention

DISCUSSION

The obtained demographic data showed that the subjects in the two groups were almost identical concerning couples’ age, couples’ age difference, number of children, length of marriage, couples’ education level, couples’ occupation, current and previous types of delivery, and wanted or unwanted pregnancies. So, the sampling was appropriate and the results are trustable. Our obtained results showed that educational intervention led to improvement of couples’ sexual function during pregnancy. Paired t-test showed a significant difference in the mean scores of sexual function before and after intervention between the two groups (P < 0.001) [Table 3]. This significant difference reveals the positive effect of sex education on improvement of couples’ sexual function during the pregnancy period. The subjects in face-to-face group could express their problems more conveniently due to less shyness they felt (rooted in Iranian culture) and asked more questions and, consequently, received more efficient answers. On the other hand, group education facilitated expression of sexual problems and sharing them with others, which resulted in opening new issues revealing the educational needs of other subjects in such a way that they received their answers in a shorter time compared to face-to-face education. The study of Shahsiya on sex education revealed the effects of education on marital satisfaction, positive feeling of couples’ closeness and friendship, and increase of marital relationship and satisfaction, which are consistent with the present study.[32] Other studies have obtained similar results. Mahmudi et al.,[20] Fentahun,[21] and Sanchez et al.[33] all reported that sexual education played a role not only in physical and sexual health but also in mental health and prevention of sexual problems. Norani also showed a significant direct correlation and association between sexual knowledge and attitude with marital satisfaction.[34] In the study of Moradi et al., education could not have any effect on couples’ sexual function due to cultural limitations, group education in educational classes, as well as limitation in clear expression of sexual problems, which were considered in the present study.[35] In women's group, mean scores of sexual function showed a significant increase after intervention in the two groups of face-to-face and group education (P < 0.001), but there was no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.06) [Table 1].

Mean scores of sexual function showed a significant increase after intervention in the two groups (P < 0.001) and there was a significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.003) (men's sexual function was more in face-to-face education compared to group education) [Table 2]. Results showed that the need for education was much higher in women's group, and both educational methods were effective. There are controversial results about men's and women's differences concerning sexual function. In the study of Khamsehee, women with mental imaginations and cultural stereotypes such as obedience, shyness, sensitivity to other's needs, affection, and making mutual understanding and being emotional in their sexual role framework reported more sexual dissatisfaction with sexual behaviors.[37] Meanwhile, women with a manhood role framework such as independency, self-sufficiency, defending their beliefs, daringness, leadership, and other manhood characteristics and who had combined these features with their female sexual role framework reported no sexual dissatisfaction. Therefore, sexual education results in correction of beliefs and incorrect information and helps the individuals acquire proper knowledge and attitude and improve their sexual behaviors, although in a study conducted by Norani et al., no significant difference was observed between men and women concerning their sexual knowledge and attitude and their effect on marital satisfaction.[36] In the studies of Sumer,[37] Huston et al.,[38] Kilmann and Vendemia,[39] and Aiquaiz et al.,[40] a significant difference was observed between men's and women's sexual function. In these studies, the men were more easy-going concerning sexual problems, compared to women, and paid more attention to obtain pleasure. They also expressed that sexual knowledge and attitude were different among men and women, resulting in a different effect on their sexual function, which is in line with the present study. Meanwhile, Shahsiya observed no significant difference between men and women in their sexual satisfaction after education, which is not in line with the present study. As mentioned before, there was no significant difference in the type of education for women, but face-to-face method was more effective for men. Due to the prevailing Iranian culture, talking about sexual problems in a group is difficult for the couples,[2] but through face-to-face education, they can ask their questions more conveniently and receive more sexual knowledge and attitude in return. They also express their wrong beliefs and cultures more easily and are less afraid of being teased.

Some of the men faced sexual disorders that resulted from their lowered sexual relationship due to fear to injure the fetus and feel guilty, which was consistent with the studies of Bayrami et al.,[19] Ebrahimiyan et al.,[4] Abozari et al.,[41] and Li Liu et al.[8]

In the present study, some of the men believed they were sex heroes and mentioned that through stopping sexual relationship with their spouses during pregnancy, they protected the fetus and their wives. Meanwhile, their spouses did not believe so and thought they were sexually disabled, not attractive, and were left by their couples, which is consistent with the studies of Gashtasbi,[42] Bayrami et al.,[19] and Naldoni et al.[18] on women's feelings during pregnancy. Talking about sexual issues resulted in expression of suppressed desires of the couples, which was observed more in face-to-face education, especially among men who speak about their sexual beliefs less. The couples also learned to speak about the sexual problems and needs with each other. Results showed that mean total scores of couples’ sexual function showed a significant increase in both face-to-face (P < 0.001) and group (P < 0.001) education groups after intervention, but there was no significant difference between the groups after intervention (P = 0.104) [Table 3]. Therefore, these two educational methods are quite the same and have equal effect on improvement of couples’ sexual function during pregnancy, which is consistent with the results of Mohammadi et al.[43] and Blorchi et al.[29] concerning the effect of educational methods. Therefore, the findings showed that education can be directly associated with couples’ sexual function during pregnancy.

CONCLUSION

Our obtained results and the results of other studies showed that couples’ sexual disorder has a high prevalence during pregnancy and leads to disturbance in couples’ marital relationship, which necessitates holding classes and courses on sexual health education with the approach of pregnancy period parallel to prenatal care, by health providing personnel, especially midwifery professionals. It should be noted that education was found to have a treatment role in the present study, as the couples with a sexual function disorder were treated after education and showed an improvement in their sexual function. Contrary to other studies on the awareness and attitudes about sexual problems during pregnancy, couples’ sexual function was investigated in the present study and education resulted in an improvement of sexual relationship. This directly has an effect on continuation of a successful marital relationship and pregnancy period when the couples need each other more. Education can be conducted personally or in group. With regard to cultural shyness and the convenience and safety regarding face-to-face education in the Iranian society, this method is suggested to involve discussion of sexual problems. Group education is also cost-effective, can cover a high number of participants, and can be applied depending on specific time and conditions.

Empowerment of midwives with scientific and counseling knowledge as they are the providers of maternal health, which forms public health, holding continuing education courses and scientific workshops in this context, and formation of an educational atmosphere in perinatal care are among the suggested strategies to improve sexual health and tighten couples’ relationship during pregnancy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This article extracted from M. Sc. thesis in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. (Maryam Mohammadi Mahdiabadzade) by project number 392369, IRCT code: IRCT2014080518500N2. This article was derived from a research project approved by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The researchers appreciate the vice chancellery for research for its financial support, and the vice chancellery for health, Clinical Research Development Center and the staff of selected health care centers in Isfahan, as well as those who helped them with this project.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Norani SS, Jonidi A, Shakeri MT, Mokhber N. Comparison of sexual satisfaction in fertile and infertile women attending public centers in Mashhad. J Reprod Infertil. 2008;10:269–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson CE. Sexual Health during Pregnancy and the Postpartum (CME) J Sexual Med. 2011;8:1267–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbacioglu A, Bakir VL, Akbayir O, Cilesiz Goksedef BP, Akca A. The role of pregnancy awareness on female sexual function early gestation. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1897–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebrahimiyan A, Heydari M, Saberi SS. Comparison sexual disorders in women with pregnancy time before that. Sem Med Sci Mag. 2010;1:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pauleta JR, Pereire NM, Graca LM. Sexuality during pregnancy. J Sex Med. 2010;7:136–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serati M, Salvatore S, Siesto G, Cattoni E, Zanirato M, Khullar V, et al. Female sexual functionduring pregnancy and after childbirth. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2782–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fok WY, Chan, SY, Yuen P. Sexual behavior and activity in Chinese pregnant women. J Acta Obstetricia ET Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2005;84:934–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Liu H, Hsu P, Chen K. Sexual activity during pregnancy in Taiwan: A Qualitative Study. Sex Med. 2001;1:54–61. doi: 10.1002/sm2.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones C, Chan C, Farine D. Sex in pregnancy. CMAJ. 2011;183:815–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prado DS, Lima RV, de Lima LM. Impact of pregnancy on female sexual function. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2013;35:5–9. doi: 10.1590/s0100-72032013000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tosun G, Gördeles B. Evaluation of Sexual Functions of the Pregnant Women. J Sex Med. 2001;11:46–53. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbacioglu Esmer A, Akca A, Akbayir O, Goksedef BP, Bakir VL. Female sexual function and associated factors during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013;39:1165–72. doi: 10.1111/jog.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erenel AS, Eroglu K, Vural G, Dilbaz B. In What Ways Do Women in Turkey Experience a Change in Their Sexuality During Pregnancy? J Sex Med. 2011;29:207–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdo CH, Oliveira WM, Jr, Moreira ED, Jr, Fittipaldi JA. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and correlated conditions in a sample of Brazilian women: Results of the Brazilian study on sexual behavior (BSSB) Int J Impotence Res. 2004;16:160–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fok WY, Chan LY, Yuen PM. Sexual behavior and activity in Chinese pregnant women. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2005;84:934–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sayle AE, Savitz DA, Thorp JM, Jr, Hertz-Picciotto I, Wilcox AJ. Sexual activity during late pregnancy and risk of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:283–9. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto AC, Baracat F, Montellato ND, Mitre AI, Lucon AM, Srougi M. The short-term effect of surgical treatment for stress urinar incontinence using sub urethral support techniques on sexual function. Int Braz J Urol. 2007;33:822–8. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382007000600011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naldoni LM, Pazmiño MA, Pezzan PA, Pereira SB, Duarte G, Ferreira CH. Evaluation of Sexual Function in Brazilian Pregnant Women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2011;37:116–29. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2011.560537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bayrami R, Satarzade N, Ranjbar F, Zachariah M. Sexual dysfunction and some related factors in pregnancy. Fertil Infertil J. 2008;9:271–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahmudi GH, Hassan Zade R, Niyaz AK. The effect of sex education on family health in the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences students, Magazine services medical sciences health and treatment knowledge horizon Gonabad. Q Ofoghe Dan. 2007;13:64–70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fentahun N, Assefa T, Alemseged F, Ambaw F. Parents’ perception, students’ and teachers’ attitude towards school sex education. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012;22:99–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jalali K, Nahidi F, Amirali F, Akbari S, Alavi H. Methods when appropriate reproductive health of girls, parents and teachers view Gorgan. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2010;12:84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murtagh J. Female sexual function, dysfunction, and pregnancy: Implications for practice. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55:438–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michael L, McDaniel Counseling on Sexuality in Pregnancy the Female pation. J Female Patient. 2010;5:42–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jahanfar SH, Molaeenezhad M. 1st ed. Esfahan: Salemi; 2003. Textbook of Sexual Disorders; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsa M. 6th ed. Tehran: Maharat; 2011. Teory of learning psychology; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aibposh S. Impact on the Trans-theoretical Model-based learning model to get vitamins female students in secondary schools. J Hayat. 2009;16:15–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamalifard M. Depending on the effect of education on knowledge, attitudes and dietary behavior of pregnant women. Iran J Med Educ. 2011;12:686–97. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blorchi FF, Neshapori M, Abed SJ. Comparison of Individual and Group training, knowledge, attitudes and skills to care for patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Iran J Nurs. 2009;22:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shabani H. 8th ed. Vol. 2. Qom: Mehr; 2012. Skills training-teaching methods, techniques; pp. 194–227-8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boer A, Melchers D, Vink S. Real patient learning integrated in a preclinical block musculoskeletal disorder. Does it make a difference? Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1029–37. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1708-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shahsiya M. The impact of education on improving marital satisfaction city. J Health Sys Res. 2010;6:690–97. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez ZM, Nappo SA, Cruz JI, Carlini EA, Carlini CM, Martins SS. Sexual behavior among high school students in Brazil: Alcohol consumption and legal and illegal drug use associated with unprotected sex. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013;68:489–94. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(04)09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norani PR, Besharat M, Yosofi S. Examine the relationship between knowledge and sexual attitudes and marital satisfaction in couples living in the complex for young researchers at Shahid Beheshti University. J Reprod Infertil. 2007;6:27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moradi Z, Shafiabadi A, Sodani M. Effective communication training on marital satisfaction in mothers of elementary school students in the city of Khorramabad. Educ Res. 2008;5:114–97. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khamsee A. Examine the relationship between sexual behavior and gender role stereotypes in the two groups of married students: A comparison of the sexual behavior of women and men in the family. Q Fam Res. 2006;2:326–39. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sumer Z. Effects of Gender and Sex-Role Orientation on Sexual Attitudes among Turkish University Students. Soc Behav Pers An Int J. 2013;41:995–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huston TL, Caughlin JP, Houts RM, Smith SE, George LJ. The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80:237–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kilmann PR, Vendemia JM. Partner discrepancies in distressed marriages. J Soc Psychol. 2013;153:196–211. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2012.719941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.AlQuaiz A, Kazi A, Muneef M. Determinants of sexual health knowledge in adolescent girls in schools of Riyadh-Saudi Arabia: A cross sectional study. BMC Women's Health. 2013;13:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abozari G, Najafi F, Kazemnejad A, Rahimikiyan F, Shariyat M, Rahnama P. Comparison of sexual functioning in primiparous women Vchndza. J Nurs Midwifery Tehran Univ Med Sci. 2011;18:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gashtasbi A. Sexual dysfunction and its relationship with fertility variables in Khglylvyh Kohkiluyeh. Q Payesh. 2007;7:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohammadi N, Tizhosh M, Seyedshohadae M, Haghani H. Comparison of two methods of group training and individual training on knowledge and anxiety in patients hospitalized for coronary angiography. J Nurs Midwifery Tehran Univ Med Sci. 2012;18:44–53. [Google Scholar]