Abstract

Our previous studies demonstrated that transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUCB-MSCs) into the hippocampus of a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (AD) reduced amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and enhanced cognitive function through paracrine action. Due to the limited life span of hUCB-MSCs after their transplantation, the extension of hUCB-MSC efficacy was essential for AD treatment. In this study, we show that repeated cisterna magna injections of hUCB-MSCs activated endogenous hippocampal neurogenesis and significantly reduced Aβ42 levels. To identify the paracrine factors released from the hUCB-MSCs that stimulated endogenous hippocampal neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, we cocultured adult mouse neural stem cells (NSCs) with hUCB-MSCs and analyzed the cocultured media with cytokine arrays. Growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15) levels were significantly increased in the media. GDF-15 suppression in hUCB-MSCs with GDF-15 small interfering RNA reduced the proliferation of NSCs in cocultures. Conversely, recombinant GDF-15 treatment in both in vitro and in vivo enhanced hippocampal NSC proliferation and neuronal differentiation. Repeated administration of hUBC-MSCs markedly promoted the expression of synaptic vesicle markers, including synaptophysin, which are downregulated in patients with AD. In addition, in vitro synaptic activity through GDF-15 was promoted. Taken together, these results indicated that repeated cisterna magna administration of hUCB-MSCs enhanced endogenous adult hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptic activity through a paracrine factor of GDF-15, suggesting a possible role of hUCB-MSCs in future treatment strategies for AD.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is an incurable neurodegenerative disease, and to date, the search for effective treatments has been unsuccessful [1,2]. A number of hypotheses, including the amyloid-β (Aβ), tau, and cholinergic hypotheses [3], have been proposed to explain the underlying mechanisms of AD. Due to the diffuse cortical involvement of the brain in AD, in contrast to the relatively focal pathology of Parkinson's disease, regenerative medicine approaches involving stem cells have long appeared to be implausible for the treatment of AD. However, a promising alternative approach is emerging, which involves paracrine-acting factors produced by stem cells and that could possibly facilitate endogenous tissue regeneration and neuroprotection [4–8].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) secrete proteins that inhibit apoptosis and inflammation, modulate the immune response in damaged tissues [9], and promote endogenous neurogenesis and neuroprotection [10]. These findings are consistent with our recent findings in a transgenic mouse model of AD that soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and galectin-3/decorin/progranulin, which are released from human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells (hUCB-MSCs), act in amyloid removal and as antiapoptotic effectors, respectively [11–13]. In addition, we found that transplantation of hUCB-MSCs improved memory deficits in an AD mouse model [14,15], although the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

Despite being allogeneic stem cells, hUCB-MSCs are the most primitive and immunologically appropriate stem cells for human therapy [16]. To explore possible clinical applications of hUCB-MSCs, they were transplanted into the brain parenchyma of patients with AD in a Phase-I clinical trial (ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT01297218). The results of that study suggested that parenchymal injections of hUCB-MSCs caused no serious adverse effects during the 12-week follow-up period [17]. To examine therapeutically effective outcomes, we sought possible approaches for the periodic and repeated administration of hUCB-MSCs.

In the present study, we periodically administered hUCB-MSCs into the cisterna magna up to three times in AD model mice. Compared with single administration of hUCB-MSCs, repeated administration resulted in significant increases in toxic Aβ clearance, the population of hippocampal neural stem cells (NSCs), number of differentiated mature neurons, and synaptic activity of mature neurons. These phenomena occurred because of growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15), which is an hUCB-MSC-secreted paracrine factor. Our results suggested that GDF-15, which was secreted from hUCB-MSCs delivered through the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), was a key paracrine factor that promoted the increase in endogenous adult hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptic activity.

Materials and Methods

Cell preparation

The isolation and culturing of hUCB-MSCs have been described in previous reports, and written informed consent was obtained from all pregnant mothers [11,12,18]. All hUCB-MSCs were kindly provided by Dr. Y.S. Yang (MEDIPOST Co., Ltd., Gyeonggi-Do, Republic of Korea). The established hUCB-MSC lines were maintained in a cell factory in accordance with good manufacturing practice guidelines at MEDIPOST Co., Ltd., and were tested according to the criteria of the International Society of Cell Therapy for surface antigen expression, mesodermal differentiation, and proliferation rate. The mouse NSCs were cultured according to previously described methods [19]. Briefly, 6-month-old C57BL/6 mice were sacrificed, and the subventricular zone (SVZ) and hippocampi were collected. The dissected brain tissues were incubated in 0.25% trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Gibco, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) at 37°C for 10 min, and then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cell pellets obtained after centrifugation were disassociated by gentle pipetting with neurobasal medium containing B-27 (2%; Life Technologies), N-2 supplement (1%; Life Technologies), l-glutamine (2 mM; Life Technologies), penicillin/streptomycin (1×; Life Technologies), 20 ng/mL of epidermal growth factor, and 20 ng/mL of basic fibroblast growth factor (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC, St. Louis, MO). The adult NSCs (2 × 104 cells/cm2) were cultivated on an untreated cell culture plate (Eppendorf; Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) in a sphere form to allow for expansion. For the coculture experiments, the neurospheres were dissociated with Accutase® (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC) and single NSCs (1 × 104 cells/cm2) were cultivated on a plate coated with 20 μg/mL of poly-d-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC) and 4 μg/mL of laminin (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC). The hUCB-MSCs (1 × 104 cells/cm2) were cocultured in the upper chamber (pore size, 1 μm), and mouse NSCs were cocultured in the lower chamber of a Transwell chamber (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). We used trypan blue exclusion tests to measure cell viability. For the generation of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled hUCB-MSCs, hUCB-MSCs were transduced with a lentivirus (KeraFAST FCT003; Kerafast, Inc., Boston, MA) containing the GFP reporter gene. The lentiviral transduction procedure was conducted as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, the multiplicity of infection of three of the lentiviral particles was used to transduce hUCB-MSCs in complete growth medium containing 10 μg/mL of Polybrene® (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC). After an 8-h incubation, the medium was replaced with fresh complete growth medium and cultivated for 48 h. For the selection of transduced hUCB-MSCs, 1 μg/mL of puromycin was added to the complete growth medium, and the hUCB-MSCs were cultured for 7 days to obtain hUCB-MSCs that were more than 90% GFP positive.

Animal studies

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MEDIPOST Co., Ltd. All the animal procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved protocols. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Samsung Biomedical Research Institute (SBRI). The SBRI is an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International)-accredited facility and abides by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (ILAR) guide. Double transgenic mice (Mo/Hu APPswe PS1dE9: APP/PS1; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were maintained, and 10-month-old APP/PS1 mice or C57BL/6 littermates were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of Zoletil™ (VIRBAC Coporation, Fort Worth, TX)/Rompun™ (Bayer Korea, Seoul, Korea). They were then fixed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL) for hUCB-MSC transplantation. First, for the parenchymal injection, 3 μL of the cell suspension (5 × 104 cells/hippocampus) or recombinant GDF-15 was injected into the bilateral dentate gyri. The hUCB-MSCs were stereotactically inoculated into the hippocampal area (AP: −1.82, L: ± 0.5, DV: −2.1, with reference to the bregma) of the mice in the stereotaxic apparatus with a sterile Hamilton syringe fitted with a 26-gauge needle (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV) and a microinfusion pump (KD Scientific, Inc., Holliston, MA). The cell suspension was delivered at 0.5 μL/min. Mice received intraperitoneal injections of BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC) (50 mg/kg in PBS containing 0.007 M NaOH) twice daily for 24 h with the intraparenchymal administration of GDF-15. For the second part of the experiment, which involved administration of hUCB-MSCs into the CSF system through the cisterna magna, the mice were anesthetized and positioned in a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting Co.) such that the cisterna magna was at its highest point. An operating microscope was used to visualize the atlanto-occipital membrane, and 15 μL of hUCB-MSCs (1 × 105 cells) was injected with a Hamilton syringe (25 μL, 26-gauge) and a microinfusion pump (1 μL/min) [20]. For quantification of the hUCB-MSCs remaining in the brain tissues after the intraparenchymal and cisterna magna injections, homozygous athymic rats (Orient Bio, Inc., Seoul, South Korea) were used regardless of their gender.

Cytokine antibody array

Growth medium was collected from the NSCs, hUCB-MSCs, and cocultures of NSCs and hUCB-MSCs. To detect the secreted proteins, a Human Cytokine Antibody Array 9 (RayBiotech, Inc., Norcross, GA) was conducted according to the manufacturer's protocol. Membranes were incubated in blocking buffer at room temperature (RT) and in each conditioned medium overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with diluted biotin-conjugated anticytokine antibodies (1:20) for 2 h at RT. After another washing step, the membranes were incubated in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (1:1,000) for 2 h at RT. The signals were detected with a ChemiDoc system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) and quantified with ImageJ software (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Treatment with siRNA

GDF-15 siRNA and scrambled control siRNA were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., (Waltham, MA). The hUCB-MSCs were treated with GDF-15 siRNA for 6 h in the presence of Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Life Technologies). These cells were cultured in complete media overnight and cocultured with mouse NSCs. Control siRNA with at least four mismatches to any human, mouse, or rat gene was used.

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA from the cells was obtained with TRIzol (Life Technologies) according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. cDNA was synthesized from the total RNA with superscript II polymerase (Life Technologies) and oligo(dT) primers (Life Technologies). The polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for β-actin (ACTB gene) and GDF-15 were run with 10 pmol of the following gene-specific primers in a total volume of 20 μL: ACTB forward primer (5′-TCCTCCCTGGAGAAGAGCTA-3′) and ACTB reverse primer (5′-AGGAGGAGCAATGATCTTGATC-3′); human-specific GDF-15 forward primer (5′-TCCTCCCTGGAGAAGAGCTA-3′) and human-specific GDF-15 reverse primer (5′-AGGAGGAGCAATGATCTTGATC-3′). The PCR products were run on 2% agarose gels for semiquantitative gene expression analyses.

Real-time PCR for the quantitative analysis of hUCB-MSCs in brain tissue

The standard curve for the quantitative analyses of real-time PCR was generated with a mixture of athymic rat CSF and the following quantities of hUCB-MSCs: 5 × 10 (0.005%), 1 × 102 (0.01%), 5 × 102 (0.05%), 1 × 103 (0.1%), 1 × 104 (1.0%), and 1 × 105 (10%). Rat brain tissue was lysed with TissueLyser (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). DNA extraction from these mixtures was performed with a DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Inc.). We used a LightCycler® 480 system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) to examine the human-specific polymerase (RNA) II (DNA-directed) polypeptide A (POLR2) with a forward primer (5′-CCTCCAGGTGGTTCAGAGG-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-AGTTCCAACAATGGCTACCG-3′) that were designed by the Roche Universal ProbeLibrary Assay Design Center (Roche Diagnostics). The PCR cycle consisted of initial denaturation (10 min at 95°C), amplification for 45 cycles (denaturation for 10 s at 95°C, annealing for 30 s at 60°C, and extension for 1 s at 72°C), and final elongation (30 s at 40°C).

Immunoblot analysis and immunohistochemistry

Cell extracts and tissues were prepared by ultrasonication (Branson Ultrasonics, Slough, United Kingdom) in buffer containing 9.8 M urea, 4% 3-((3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 130 mM dithiothreitol, 40 mM Tris-Cl, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. The protein levels were measured with Bradford assays (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The protein extract (20 μg) was loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels for electrophoresis. The gels were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. For the immunoblot analysis, NuPAGE 12% and 4%–12% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies) were used. Each membrane was incubated with anti-SRY-box2 (SOX2; 1:1,000), anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; 1:500), anti-nestin (1:1,000), anti-doublecortin (DCX; 1:500), anti-synaptophysin (SYP; 1:500), anti-vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP; 1:1,500), anti-syntaxin (STX; 1:1,000), anti-synaptotagmin (SYT; 1:500) (Abcam plc, Cambridge, United Kingdom), anti-β-actin (1:5,000; Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC), anti-neprilysin (NEP, 1:500; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN), or anti-Aβ42 (1:500; Novus Biologicals, LLC, Littleton, CO) antibodies. A GDF-15 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Inc.) and a kit for detecting Aβ42 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) were used according to the manufacturers' instructions. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), euthanized mice were immediately fixed by cardiac perfusion with PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. After perfusion, postfixation was conducted overnight at 4°C, and the brains were incubated in 20% sucrose at 4°C until they were equilibrated. Sequential 30-μm coronal cryosections were prepared with a cryostat microtome (CM1850UV; Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) and stored at −20°C. The following antibodies were used: anti-SOX2 (1:200), anti-Ab (1:200), anti-DCX (1:1,000), anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; 1:200), anti-SYP (1:100), and anti-GDF-15 (1:250; Abcam plc), anti-neuronal nuclei (NeuN; 1:100), and anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2, 1:200; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Alexa Fluor 488, Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Europe Ltd., Newmarket, United Kingdom), biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA), and a Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) were used to visualize the immune complexes, and nucleus staining was performed by using 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were acquired with an LSM 700 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) and a light microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Aβ plaques were analyzed with the Metamorph 7.1.2 software (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA). For the negative controls, we stained the brain tissues with only the secondary antibodies as a control for no primary antibody. The cells in the selected images were manually counted with ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Optical setup for cellular imaging and data analysis

The hippocampal CA3–CA1 regions were dissected from 1-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats, dissociated, and plated onto polyornithine-coated coverslips for 14–21 days, as described previously [21]. The constructs were transfected 8 days after plating, and imaging was performed 14–21 days after plating. The coverslips were mounted in a laminar flow perfusion and stimulation chamber on the stage of a custom-built laser-illuminated epifluorescence microscope. Epifluorescent images of live cells were acquired with an Andor iXon Ultra (model: DU-897U-CS0-#BV) back-illuminated electron multiplying charge-coupled device camera. A diode-pumped solid-state 488-nm laser (OBIS 488 nm; Coherent, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) in the transistor–transistor logic modulation was utilized for excitation of pHluorin during acquisition. Fluorescence excitation and collection were done through a 40 × 1.3 NA Fluar Zeiss objective with 515- to 560-nm emission and 510-nm dichroic filters for pHluorin. Action potentials were evoked by passing 1-ms current pulses, which yielded fields of 10 V/cm through platinum–iridium electrodes. The cells were continuously perfused (0.5–1.0 mL/min, 30°C) in Tyrode's solution containing (in mM) 119 NaCl; 2.5 KCl; 2 CaCl2; 2 MgCl2; 25 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), buffered to pH 7.4; 30 glucose; 10 μM of 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC); and 50 μM of d,l-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV; Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC). Applications of NH4Cl were made with 50 mM of NH4Cl instead of 50 mM of NaCl, and this was buffered to pH 7.4. GDF-15 was applied in a bath over the course of the experiment. The obtained images were analyzed with ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) with a plug-in (Time Series Analyzer). All of the functionally visible varicosities were selected for analysis by testing their responsiveness to the test stimuli of 100 action potential (100AP) trains at 10 Hz. Fluorescence time course traces were analyzed with Origin Pro (version 8.0) traces. The peak amplitude of the 100AP was selected at the end of the stimulation at 10 Hz for 10 s, and the peak of NH4Cl was the mean value of the plateau area, as previously described [22].

Results

Extended hUCB-MSC efficacy in Aβ clearance through repeated injections in the cisterna magna

Previous studies have indicated that engrafted MSCs lack long-term survival in brain parenchyma [23–25]. Before the comparison of the effects of single versus repeated cisterna magna injections on Aβ clearance, we initially examined the survival and biodistribution of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-administered hUCB-MSCs according to the guidelines of the Korean Food and Drug Administration. First, we quantitatively analyzed the hUCB-MSCs that remained in brain tissues after parenchymal or cisterna magna injections with quantitative PCR. The results showed that the number of hUCB-MSCs was consistently decreased after administration through both injection routes (Supplementary Fig. S1Aa, b; Supplementary Data are available online at www.libertpub.com/scd). For the single administration into the brain parenchyma of the hippocampus, hUCB-MSCs lived for no longer than 8 weeks (Supplementary Fig. S1Aa), whereas the cells were not completely vanished on the 8 weeks after the third administration through cisterna magna (Supplementary Fig. S1Ab). In addition, the number of hUCB-MSCs that remained in brain tissues after three injections in the cisterna magna every 4 weeks was 3.55-fold higher [20] than that after a single administration (Supplementary Fig. S1Ac). These suggested that periodical and repeated administration was optimal for the purpose of our study (Fig. 1A). Second, an IHC analysis of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled hUCB-MSCs was performed to detect the biodistribution of hUCB-MSCs within the brain parenchyma. After single and repeated administrations of GFP-labeled hUCB-MSCs through the cisterna magna, the distribution of cells was determined by detecting the GFP fluorescent signal (Fig. 1B). GFP-positive hUCB-MSCs were observed in the brain parenchyma, including the thalamus, SVZ, dentate gyrus (DG), and cortex. The comparison of hUCB-MSCs at 4 and 10 weeks after a single injection indicated that the living hUCB-MSCs would most likely disappear after 10 weeks of the single injection. However, the repeatedly injected hUCB-MSCs were alive 10 weeks after the first injection and their amounts in the brain parenchyma were similar to those observed 4 weeks after a single injection. These data suggested that repeated injections with a 4-week interval were more beneficial than a single injection (Fig. 1B).

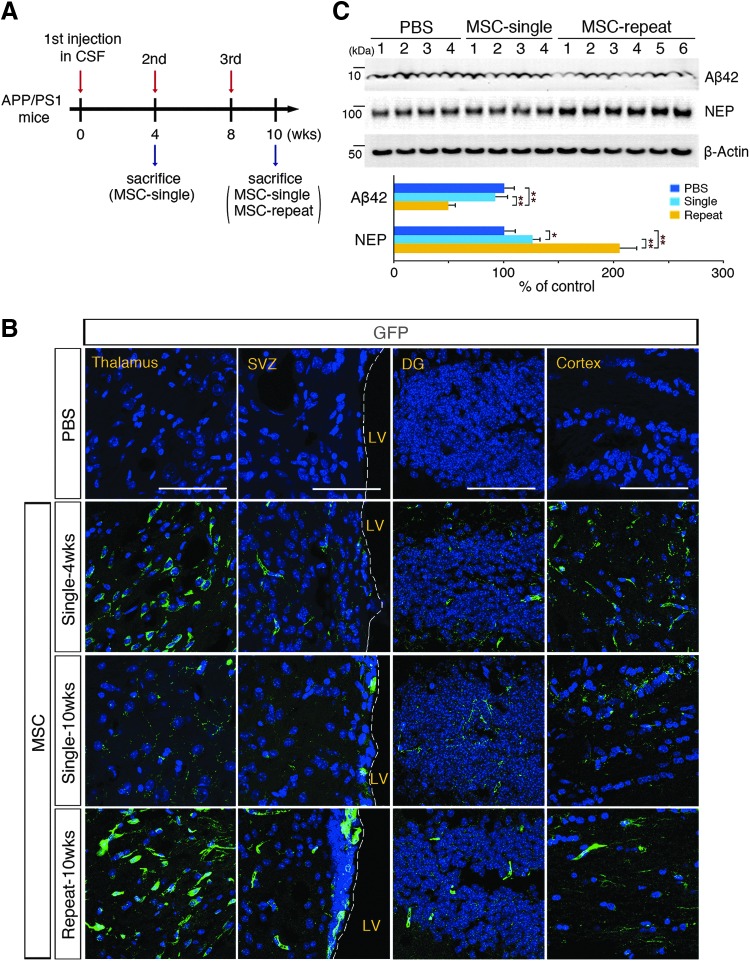

FIG. 1.

Administration of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUCB-MSCs through the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) reduces the appearance of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques after localizing to the brain parenchyma. (A) Schematics of single and repeated injections of hUCB-MSCs (1 × 105 cells) into the cisterna magna of APP/PS1 mice and the schedule of animal sacrifice. (B) Brains injected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled hUCB-MSCs were sectioned and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The images were analyzed with a confocal microscope. At each point of sacrifice, GFP signals were observed in the thalamus, subventricular zone (SVZ), dentate gyrus (DG), and cortex [n = 4 for phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-administered controls, n = 4 for single injections, n = 6 for repeated injections, scale bar = 100 μm]. (C) hUCB-MSCs (1 × 105 cells) were injected into the cisterna magna of six APP/PS1 mice by single or repeated injections. Two weeks after the third injection, the brains were extracted and analyzed for the level of Aβ42 and neprilysin (NEP) with immunoblotting (*P < 0.05, **P <0.005 vs. PBS controls or a single injection).

Third, we investigated the effects of single versus repeated injections on the expression of neprilysin (NEP) and Aβ clearance. We recently demonstrated that a single injection of hUCB-MSCs into the brain parenchyma of AD mice reduces the levels of soluble and insoluble Aβ through the overexpression of NEP, which is an Aβ-degrading enzyme [11]. To determine whether this effect could be replicated by hUCB-MSC delivery through the CSF, we measured the endogenous levels of NEP and Aβ in whole brains with immunoblots after single and repeated cisterna magna injections of hUCB-MSCs. As expected, the NEP expression levels were increased by 1.26- and 2.05-fold after single and repeated injections, respectively, whereas the Aβ42 levels were reduced, 8.3% and 50.8%, respectively (Fig. 1C). These results were validated with ELISA and IHC (Supplementary Fig. S1B, C, respectively). In summary, these data showed that hUCB-MSCs repeatedly administered through the CSF penetrated into the brain parenchyma and survived up to 8 weeks. In addition, the hUCB-MSCs substantially reduced Aβ levels in the brains of AD mice; these effects were enhanced after repeated injections compared with a single injection.

Effects of hUCB-MSCs in endogenous adult hippocampal neurogenesis

In AD pathogenesis, the hippocampus, which contributes to learning and memory, is one of the first brain regions to be affected [26]. Our previous studies showed that spatial working memory was improved when hUCB-MSCs were directly administered into the hippocampi of AD mice [14,15]. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms of these effects are not clearly understood. Because CSF-administered hUCB-MSCs were found in the two adult neurogenic regions (the SVZ and DG) (Fig. 1B), we speculated that there might be a possible role of hUCB-MSCs in the regulation of endogenous adult neurogenesis and this could restore the cognitive functions of AD mice.

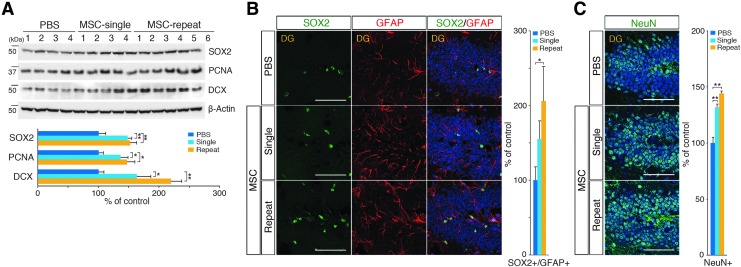

The levels of adult NSC proliferation and differentiation were measured in hUCB-MSC-injected whole brain protein extracts. Both single and repeated injections of hUCB-MSCs significantly increased the levels of adult NSC proliferation [SRY-box2 (SOX2) [27], proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) [28]] and differentiation [doublecortin (DCX) [29]] markers compared with the control levels (Fig. 2A). To investigate whether these immunoblot assay results were due to either the increased expression of the marker or increased NSC populations in the brains, we stained for markers of NSCs [SOX2 and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)] and mature neurons [neuronal nuclei (NeuN)] in the DG [30,31] (Fig. 2B, C, respectively). A quantitative IHC analysis indicated that the single and repeated administrations of hUCB-MSCs enhanced adult hippocampal NSC populations by 1.55- and 2.06-fold, respectively. In addition, the mature neuron populations in the DG increased by 1.32- and 1.44-fold after single and repeated administrations of hUCB-MSCs, respectively. We also measured the population changes in NSCs and neuroblasts in the SVZ, which is another adult neurogenic compartment that has anatomical contact with CSF. After single and repeated administrations of hUCB-MSCs, the numbers of NSCs (SOX2/GFAP) were increased by 1.59- and 2.18-fold, respectively, and the numbers of neuroblasts (DCX) were increased by 1.58- and 2.00-fold, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2A, B, respectively). To validate whether these results were specifically due to the in vivo administration of hUCB-MSCs, we administered HS68 cells (human fibroblast cells) into the CSF and showed that there was no significant change in either the SVZ or hippocampal neurogenesis compared with the PBS-administered control group (Supplementary Fig. S2C–E). Altogether, these results suggested that CSF-administered hUCB-MSCs promoted adult NSC proliferation and differentiation in both DG and SVZ and repeated administration of hUCB-MSCs enhanced these effects.

FIG. 2.

Administration of hUCB-MSCs through the CSF stimulates endogenous hippocampal neurogenesis. (A) hUCB-MSCs (1 × 105 cells) were injected into the cisterna magna of six APP/PS1 mice by single or repeated injections. Two weeks after the third injection, the brains were extracted and analyzed to detect SRY-box2 (SOX2), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, and doublecortin (DCX) with immunoblotting (n = 4 for PBS controls, n = 4 for single injections, n = 6 for repeated injections, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 vs. PBS controls or a single injection). (B, C) Sections of the DG were stained with specific antibodies for neural stem cells (NSCs) (SOX2 and GFAP) and mature neurons [neuronal nuclei (NeuN)]. The graphs show the numbers of Sox2/GFAP double-positive cells [1.0:1.6:2.1 cells (PBS:Single:Repeat) per 100 DAPI-positive cells] and NeuN-positive cells [65.5:86.3:94.4 cells (PBS:Single:Repeat) per 100 DAPI-positive cells] (n = 12 sections per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 vs. PBS controls, scale bar = 100 μm).

Identification of GDF-15 as an hUCB-MSC-secreted paracrine factor for the stimulation of adult NSC proliferation in vitro

The effects of hUCB-MSCs on adult NSC proliferation were evaluated in vitro by coculturing hUCB-MSCs and mouse adult NSCs in the upper and lower sections, respectively, of a Transwell chamber as described in the Materials and Methods section. The quantification of live and dead NSCs was conducted with trypan blue exclusion tests. Direct cell–cell contact was prevented by using 1-μm pore size Transwell membranes. The number of live NSCs significantly increased in a time-dependent manner when they were cocultured with hUCB-MSCs (Fig. 3A) when cell viability was also significantly increased (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Furthermore, the levels of adult NSC proliferation markers (nestin [32], SOX2, and PCNA) were significantly upregulated in the NSCs in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3B), which suggested that hUCB-MSCs stimulate adult NSC proliferation through the secretion of soluble factors.

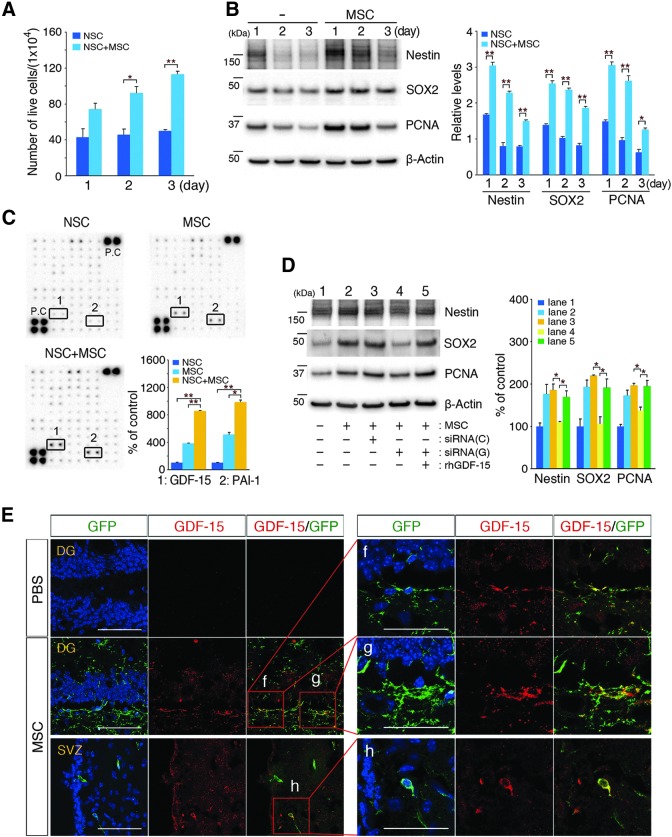

FIG. 3.

Adult hippocampal NSC proliferation is stimulated by growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15), which is secreted from hUCB-MSCs in vitro and in vivo. (A) hUCB-MSCs were cocultured with mouse adult NSCs in a Transwell chamber for 1–3 days. After coculturing, the proliferation of the NSCs in the lower chamber was measured with a trypan blue exclusion test. The graphs show the number of live NSCs (n = 4 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 vs. NSCs alone). (B) After coculturing, NSC lysates were analyzed with immunoblotting for anti-nestin, anti-SOX2, and anti-PCNA antibodies (densitometric analysis: n = 4 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 vs. NSC alone). (C) Media were collected after 1 day from NSCs (alone), hUCB-MSCs (alone), and NSCs that were cocultured with hUCB-MSCs. Cytokine arrays were conducted as described in the Materials and Methods section. The boxes that are numbered 1 and 2 indicate the localization of GDF-15 and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) for each condition. A densitometric analysis of GDF-15 and PAI-1 was conducted (n = 3 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 vs. NSCs or MSCs alone). (D) hUCB-MSCs were transfected with GDF-15 siRNA for 6 h, and then cocultured with NSCs for 24 h. Scrambled siRNA was used as a control. Lysates that were prepared from NSCs were analyzed with antibodies that were specific for nestin, SOX2, and PCNA. The densitometric analysis shows a decrease in the levels of nestin, SOX2, and PCNA because of siRNA-GDF-15 transfection. Conversely, recombinant GDF-15 was added to the siRNA-GDF-15-treated hUCB-MSCs during the NSC coculture. The densitometric analysis shows an upregulation of Nestin, SOX2, and PCNA expression due to the presence of recombinant GDF-15 (n = 3 per group, *P < 0.05 vs. siRNA-GDF-15-treated hUCB-MSCs). siRNA (C or G) indicates the siRNA control and GDF-15, respectively. (E) Each tissue section was stained with DAPI and anti-GDF-15 antibodies. The images show merged green (GFP-labeled hUCB-MSCs) and red (GDF-15) confocal images in the DG. The boxed areas were magnified and merged to analyze the colocalization of GFP-labeled hUCB-MSCs and GDF-15-secreting cells [scale bars = 100 μm in (E) and 50 μm in (f–h)].

To identify the soluble factors secreted from hUCB-MSCs, the cocultured cell media were collected and analyzed by using a cytokine antibody array. The levels of GDF-15 and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) were considerably upregulated in the cocultured media compared with controls (Fig. 3C). In addition, we attempted to identify the proteins secreted by individual cultures of hUCB-MSCs, adult NSCs, and cocultures using another cytokine antibody array (Raybiotech) that can detect 507 different proteins. Secreted GDF-15 and PAI-1 were also detected in the cocultured media at high levels (data not shown). Unlike GDF-15, there was no significant change in adult NSC proliferation after treatment with recombinant PAI-1 in vitro (data not shown). An analysis of GDF-15 mRNA using reverse transcriptase-PCR revealed that GDF-15 transcription was only upregulated in hUCB-MSCs when they were cocultured with adult NSCs in the Transwell chambers (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

To determine whether GDF-15 mediated the proliferative effects of hUCB-MSCs on adult NSCs, synthesis of the protein was inhibited in hUCB-MSCs by using GDF-15-specific siRNA. The presence of GDF-15 siRNA dramatically reduced the expression of mRNA encoding GDF-15 and the secretion of GDF-15 proteins (Supplementary Fig. S3C, D, respectively). The suppression of GDF-15 expression in hUCB-MSCs as a result of GDF-15 siRNA reduced the levels of expression of SOX2 and nestin in NSCs in cocultures (Fig. 3D). Conversely, this effect was reversed by the addition of recombinant GDF-15 to the cocultures of adult NSCs and hUCB-MSCs that had been transfected with GDF-15 siRNA (Fig. 3D). In addition, when we analyzed the expression of GDF-15 secreted from hUCB-MSCs that were delivered by CSF, hUCB-MSCs present in the brain parenchyma (green-colored: GFP-labeled hUCB-MSCs) colocalized with GDF-15 (red-colored). GDF-15-positive hUCB-MSCs were also observed in the DG and SVZ in the brains of AD mice (Fig. 3E), which suggested that hUCB-MSCs that were localized in neurogenic regions, including the DG, promoted endogenous NSC proliferation through secretion of the paracrine factor, GDF-15.

Role of GDF-15 in the stimulation of adult NSC proliferation in vitro and enhancement of the mature neuron population in the DG

Previous studies have demonstrated that GDF-15 acts as a neurotrophic factor for adult motor and dorsal root ganglion sensory neurons that promotes the survival of dopaminergic neurons [33–35]. To better understand the importance of the GDF-15 functions involved in hippocampal neurogenesis and neural development [36], we examined whether adult hippocampal neurogenesis was regulated by human recombinant GDF-15 in a concentration- or time-dependent manner. We first analyzed NSC markers from adult NSCs after treatment with 1, 20, or 100 ng/mL of human recombinant GDF-15 for 24 h. Nestin, SOX2, and PCNA were the markers most significantly upregulated after treatment with 20 ng/mL of GDF-15 (Fig. 4A). With the optimal concentration (20 ng/mL) of GDF-15 treatment for adult NSC proliferation, we analyzed NSC markers as a function of treatment duration (6, 12, or 24 h). The levels of NSC markers gradually increased in response to the duration of treatment (Fig. 4B).

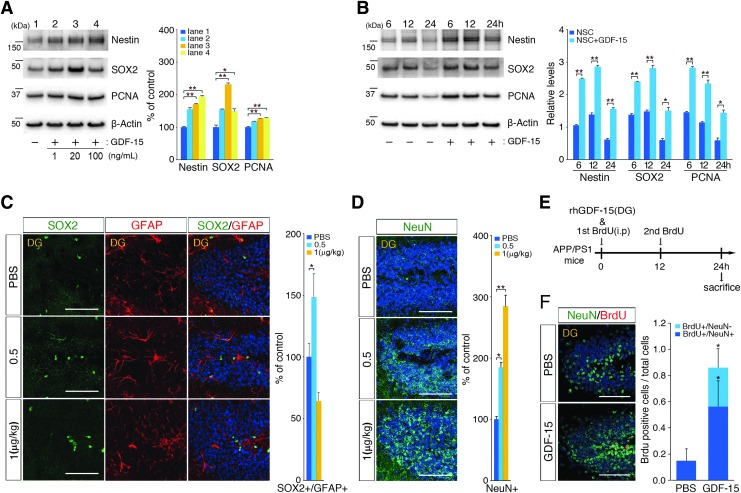

FIG. 4.

hUCB-MSCs promote GDF-15-dependent adult NSC proliferation and differentiation. (A) Recombinant GDF-15 (1, 20, or 100 ng/mL) was administered to mouse adult NSCs for 24 h, and (B) 20 ng/mL of recombinant GDF-15 was administered to mouse adult NSCs for 6, 12, and 24 h. The NSC lysates were analyzed with antibodies that were specific for nestin, SOX2, and PCNA (n = 3 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 vs. control group). (C, D) Varying concentrations of recombinant GDF-15 were injected into each hippocampus. After 24 h, sections of the DG were stained with specific antibodies for NSC (SOX2 and GFAP) and mature neuron (NeuN) markers. The graphs show the numbers of SOX2/GFAP double-positive cells [2.0:2.2:1.5 cells (PBS:Single:Repeat) per 100 DAPI-positive cells] and NeuN-positive cells [15.3:28.1:43.4 cells (PBS:Single:Repeat) per 100 DAPI-positive cells] (n = 3 for PBS, n = 4 for 0.5 μg/kg, n = 4 for 1 μg/kg, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 vs. the PBS group, scale bar = 100 μm). (E) Schematics of the recombinant GDF-15 and BrdU injections into the cisterna magna of APP/PS1 mice and the schedule for animal sacrifice. (F) After 24 h, DG sections were stained with specific antibodies for BrdU and a mature neuron marker (NeuN). The graphs show the number of BrdU-positive and NeuN-negative cells [0.2:0.6 cells (PBS:GDF-15) per 100 DAPI-positive cells], BrdU-positive and NeuN-positive cells [0.0:0.3 cells (PBS:GDF-15) per 100 DAPI-positive cells], and NeuN-positive cells (n = 3 for PBS, n = 3 for GDF-15 and BrdU injection, scale bar = 100 μm).

To understand the effects of GDF-15 in adult hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo, recombinant GDF-15 (0.5 and 1 μg/kg) was administered directly to both hippocampi of APP/PS1 mice. After 24 h of administration, the number of adult hippocampal NSCs was significantly (1.5-fold) increased in response to 0.5 μg/kg of GDF-15, whereas the 1 μg/kg of GDF-15 resulted in a 36% decrease in the NSC population (Fig. 4C). The numbers of mature neurons in the DG were significantly enhanced by GDF-15 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4D); the administration of 0.5 and 1.0 μg/kg of GDF-15 resulted in 1.84- and 2.84-fold increase in the numbers of NeuN-positive cells, respectively. Based on these results, we further examined whether GDF-15 would lead to the proliferation of adult hippocampal NSCs and their differentiation into mature neurons within 24 h. When GDF-15 was administered into the adult hippocampi, BrdU was also intraperitoneally injected every 12 h into the AD mice (Fig. 4E). The animals were then sacrificed 24 h after GDF-15 administration, and the BrdU- and NeuN-positive cells in the hippocampi were quantified. The number of double-positive cells in GDF-15-administered brains increased 3.82-fold compared with the number in the PBS-injected group (Fig. 4F), which suggested that GDF-15 stimulated adult NSC proliferation and differentiation into neurons in the hippocampus within 24 h. Together, these data indicated that GDF-15 was a causative factor that enhanced the expression of NSC markers (Nestin and SOX2) and cell proliferation markers (PCNA) in vitro and both proliferation and differentiation of NSCs in the adult DG in vivo.

Efficacy of hUCB-MSCs in the enhancement of synaptic activity in vivo and the potentiation of adult hippocampal neurotransmission through action potential stimulation by GDF-15 in vitro

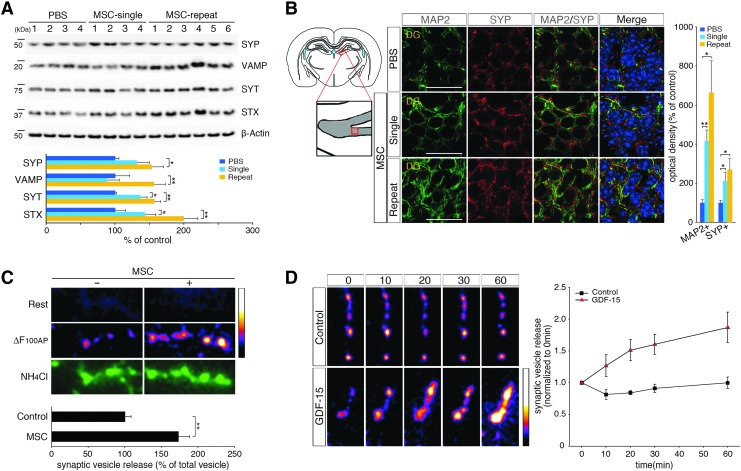

Synaptic loss is one of the main causes of neuronal death and cognitive decline in AD [3]. Synaptophysin (SYP), which is a marker of synaptic density [37], is downregulated during cognitive decline in patients with AD [38]. To determine whether improved synaptic activity could be induced by hUCB-MSCs, we analyzed the expression of the following synaptic vesicle markers: SYP [39], vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP) [40], syntaxin (STX) [41], and synaptotagmin (SYT) [41]. After injecting hUCB-MSCs into the CSF of adult AD mice, the levels of SYP, VAMP, STX, and SYT were significantly upregulated in the whole brain (SYP: 1.31-fold/1.53-fold increases, VAMP: 0.88-fold/1.56-fold increases, SYT: 1.37-fold/1.57-fold increases, and STX: 1.43-fold/2.00-fold increases after single/repeated administrations, respectively, of hUCB-MSCs) (Fig. 5A). The IHC and histological analyses revealed that SYP levels in mature DG neurons were increased by 2.70- and 1.83-fold, respectively, after repeated injections of hUCB-MSCs, which confirmed that hUCB-MSCs enhanced the expression of SYP (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. S4A).

FIG. 5.

hUCB-MSC administration through the CSF induces synaptic activity markers in vivo and potentiates hippocampal neurotransmission by action potential stimulation with GDF-15 in vitro. (A) The single and repeated administrations of hUCB-MSCs were extracted and analyzed by immunoblotting with synaptophysin (SYP), vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP), syntaxin (STX), and synaptotagmin (SYT) antibodies. (B) The brains were sectioned and immunostained with anti-microtubule (anti-MAP2) (green) for mature neurons and anti-SYP (red) and DAPI. Scale bar = 20 μm (n = 4 for PBS controls, n = 4 for single injections, n = 6 for repeated injections, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 vs. PBS controls). (C) Primary hippocampal neurons that were transfected with pHluorin-conjugated vesicular glutamate transporter1 [vGlut1-pHluorin (vG-pH)] were stimulated at 10 Hz for 10 s with or without hUCB-MSCs coculturing for 24 h. Representative vG-pH images at rest and the difference in the images for 100 action potential (100AP) stimuli (ΔF100AP) and during NH4Cl application in control and hUCB-MSCs cocultured neurons were measured (n = 21 cells for control, 33 cells for hUCB-MSCs100AP). (D) Treatment with GDF-15 potentiates the activity-driven synaptic transmission of primary hippocampal neurons. The neurons were stimulated at 10 Hz for 10 s with or without GDF-15 (20 ng/mL) for 10, 20, 30, or 60 min. Pseudocolor images show the time course of the ΔF image of the boutons that responded to stimuli of 100AP. The values of the amplitudes of 100AP responses were normalized to that of the initial response (n = 4 cells for control and 5 cells for GDF-15).

After obtaining evidence of the increased expression of synaptic vesicle markers, the neurotransmission of hippocampal neurons with action potential stimulation was measured after coculturing hUCB-MSCs and hippocampal primary neurons that were transfected with pHluorin-conjugated vesicular glutamate transporter1 (vGlut1-pHluorin; vG-pH) for 24 h. vG-pH is a highly sensitive marker of synaptic vesicle exocytosis [42]. Action potential-driven synaptic transmission was detected in the primary neurons when vG-pH responses were monitored after 100AP (10 Hz) stimuli. In contrast to vesicle release from control neurons (Control100AP = 0.091 ± 0.008, n = 21 cells), the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles in the neurons that were cocultured with hUCB-MSCs (hUCB-MSCs100AP = 0.159 ± 0.015, n = 33 cells) was significantly (1.7-fold) increased (Fig. 5C). To validate the variations in the total levels of labeled vesicle pools in control and hUCB-MSC cocultured neurons, NH4Cl was applied to the neurons. The signals between the two groups did not differ significantly (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. S4B).

As paracrine factors that are secreted from hUCB-MSCs potentiate synaptic transmission, we examined the possible role of GDF-15 in the direct potentiation of activity-driven synaptic transmission. vG-pH-transfected hippocampal primary neurons were stimulated with 100AP at 10 Hz for 10, 20, 30, or 60 min after the addition or absence of GDF-15 (20 ng/mL) (Supplementary Fig. S4C). After normalization of the values to the initial response (0 min), control neurons without GDF-15 showed the following number of responses: 0.82 ± 0.08 (10 min), 0.84 ± 0.03 (20 min), 0.91 ±0.07 (30 min), and 0.99 ± 0.09 (60 min) (Fig. 5D). In the presence of GDF-15, the responses grew to 1.27 ± 0.17 (10 min), 1.51 ± 0.16 (20 min), 1.60 ± 0.16 (30 min), and 1.87 ± 0.24 (60 min) (Fig. 5D). The application of GDF-15 resulted in the time-dependent potentiation of synaptic transmission, whereas control neurons that were treated with vehicle did not show altered synaptic transmission. In summation, the paracrine actions of hUCB-MSCs promoted not only endogenous neurogenesis but also synaptic activity in hippocampal neurons through GDF-15.

Discussion

Our previous studies have primarily focused on the hypothesis that hUCB-MSCs exert therapeutic effects in AD mice by inhibiting apoptosis [12,13] and removing toxic amyloids through secreted factors [11]. These neuroprotective effects at the cellular level restore memory loss in AD mice, and this was demonstrated in a water maze experiment [14,15]. The functional effects of MSCs in the treatment of various diseases are most likely due to secreted paracrine factors [4–8]. However, the molecular mechanisms beyond the functional effects are not yet fully understood. In the present study, we demonstrated that the repeated intrathecal delivery of hUCB-MSCs could have accumulative therapeutic effects on AD pathology and promote endogenous hippocampal NSC proliferation, neuronal population maturation, and synaptic activity in AD mice through the paracrine factor, GDF-15.

The results of the present study had two major implications regarding the development of hUCB-MSC-based therapies for AD. The first major implication was that intrathecal administration of hUCB-MSCs promoted adult neurogenesis and synaptogenesis. Our study demonstrated that endogenous adult hippocampal neurogenesis was promoted through an hUCB-MSC paracrine mechanism, which is the basis for the effects of hUCB-MSCs in AD. Unlike previous studies that demonstrated that MSCs promote neurogenesis [30,43,44], we utilized the Transwell coculture system to identify increased levels of GDF-15 secreted from hUCB-MSCs by analyzing cytokine antibody arrays. GDF-15, which is a member of the transforming growth factor superfamily [45,46], is a neurotrophic factor that affects adult motor and dorsal root ganglion sensory neurons [33,34]. It is also widely expressed in the liver, lungs, kidneys, and exocrine glands. Previous in vitro and in vivo experiments have revealed that GDF-15 is ubiquitous in the CNS and promotes the survival of dopaminergic neurons [35]. Of particular note, GDF-15 knockout mice exhibit the progressive postnatal loss of motor neurons [47] and a decrease in the proliferation and migration of adult hippocampal progenitors due to the lack of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling stimulation [36]. Similarly, our study showed that the suppression of GDF-15 synthesis in hUCB-MSCs with a GDF-15-specific siRNA resulted in an absence of stimulation of NSC proliferation, whereas addition of exogenous GDF-15 promoted the in vitro and in vivo proliferation of NSCs and the in vivo maturation of neuron populations. Taken together, these data suggest that GDF-15 from hUCB-MSCs mediates hippocampal neurogenesis in AD mice.

Besides the enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis after the repeated administration of hUCB-MSCs through the CSF, the synaptic activity of hippocampal neurons was also stimulated in AD mice due to the secretion of GDF-15. The protein levels of synaptic vesicle markers (SYP, VAMP, STX, and SYT) were increased in the hippocampus of hUCB-MSC-administered AD mice. After the coculture of primary hippocampal neurons with hUCB-MSCs, synaptic transmission in response to action potential stimuli (100AP at 10 Hz) in the neurons was significantly potentiated and this effect was specifically mediated by GDF-15. GDF-15 is thought to be a member of the growth factor superfamily. In the nervous system, growth factors might be able to activate many aspects of neural signaling pathways like neurotrophic factors do (eg, brain-derived neurotrophic factor). In the present study, we were not able to determine the exact mechanism underlying how GDF-15 potentiates synaptic activity in a short period, but there are several possibilities. First, GDF-15 might be able to activate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, which increase Ca2+ influx at the presynaptic terminal. Second, GDF-15 might be able to redistribute and enrich voltage-gated Ca2+ channels at the release site (active zone), which can increase Ca2+ influx. Third, GDF-15 might be able to affect the assembly of the synaptic vesicle fusion machinery (SNARE complex) that increases synaptic vesicle release. Overall, these findings may be related to our previous research findings that hUCB-MSCs mitigate memory loss in AD mice, which was demonstrated by water maze experiments [14,15].

The second major implication for future clinical trials is that intrathecal administration could potentially be a more advantageous route for the repeated delivery of hUCB-MSCs into the brain than direct transplantation into the brain parenchyma. The direct transplantation of hUCB-MSCs into the brain parenchyma in our Phase-I clinical trial (ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT01297218) was hampered, possibly due to the limited life span of the administered MSCs [11] and the technical limitations of repeated injections because of its high invasiveness. Therefore, a less invasive and more feasible route for the repeated administration of hUCB-MSCs into the brain was needed. CSF administration may be preferable over other routes of administration because the hUCB-MSCs were more likely to disperse and dock to the lateral ventricle walls [48] and begin migrating into the brain parenchyma. Other than this route of MSC delivery, the intravenous (IV) delivery of MSCs has been reported [49–54]. The IV delivery of stem cells is less invasive. However, it is inherently systemic, and a higher cell dosage would be required. In addition, this method can result in MSC delivery to unintended target organs, such as the lungs and liver. We demonstrated that hUCB-MSCs administered into the CSF appeared to migrate toward the brain parenchyma, including the SVZ, DG, hypothalamus, and cortex. We previously postulated that hUCB-MSCs have a strong capacity to migrate toward inflammatory sites, such as brain regions where amyloid is deposited [11,55,56]. Therefore, hUCB-MSCs could migrate from the CSF into the brain parenchyma regions that harbor inflammation that is associated with Aβ. Furthermore, areas of neurogenesis, such as the SVZ and DG, are in close proximity to the CSF, which makes intrathecal injections more plausible. Other potential benefits of intrathecal injections that were demonstrated by the present study were that intrathecally administered hUCB-MSCs reduced the amyloid burden and repeated administration of hUCB-MSCs through the CSF was more efficient than a single injection for the desired therapeutic effects in AD. Therefore, we carefully speculated that CSF administration could become a more standard procedure for delivering hUCB-MSCs to the human brain.

In conclusion, we found that the accumulative efficacy of repeatedly administered hUCB-MSCs through the CSF rather than through brain parenchymal single injections significantly influenced the removal of toxic amyloid plaques and promoted hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptic activity in mature neurons through GDF-15 in AD mice. These findings could be used as the basis for future clinical trials of hUCB-MSC therapies that involve repeated CSF administration in AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI12C1821 and HI14C3484), and Basic Research Program through the National Research Foundation of South Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2014R1A2A1A11050576). The optical imaging study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the NRF, which is funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (S.H.K. 20132100). The resource of hUCB-MSCs and the rights of all the outcomes from this article belong to MEDIPOST Co., Ltd.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Miller G. (2010). Pharmacology. The puzzling rise and fall of a dark-horse Alzheimer's drug. Science 327:1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn-Hardy K, Mohamed M, Chaudhuri AR. and Zalutsky R. (2007). How common are the “common” neurologic disorders? Neurology 68:326–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Querfurth HW. and LaFerla FM. (2010). Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 362:329–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, Kota DJ, Ylostalo J, Larson BL, Semprun-Prieto L, Delafontaine P. and Prockop DJ. (2009). Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell 5:54–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block GJ, Ohkouchi S, Fung F, Frenkel J, Gregory C, Pochampally R, DiMattia G, Sullivan DE. and Prockop DJ. (2009). Multipotent stromal cells are activated to reduce apoptosis in part by upregulation and secretion of stanniocalcin-1. Stem Cells 27:670–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karaoz E, Genc ZS, Demircan PC, Aksoy A. and Duruksu G. (2010). Protection of rat pancreatic islet function and viability by coculture with rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis 1:e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplan AI. and Correa D. (2011). The MSC: an injury drugstore. Cell Stem Cell 9:11–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohkouchi S, Block GJ, Katsha AM, Kanehira M, Ebina M, Kikuchi T, Saijo Y, Nukiwa T. and Prockop DJ. (2012). Mesenchymal stromal cells protect cancer cells from ROS-induced apoptosis and enhance the Warburg effect by secreting STC1. Mol Ther 20:417–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JY, Jeon HB, Yang YS, Oh W. and Chang JW. (2010). Application of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in disease models. World J Stem Cells 2:34–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh JY, Wang HW, Chang SJ, Liao KH, Lee IH, Lin WS, Wu CH, Lin WY. and Cheng SM. (2013). Mesenchymal stem cells from human umbilical cord express preferentially secreted factors related to neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis. PLoS One 8:e72604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JY, Kim DH, Kim JH, Lee D, Jeon HB, Kwon SJ, Kim SM, Yoo YJ, Lee EH, et al. (2012). Soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 secreted by human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell reduces amyloid-beta plaques. Cell Death Differ 19:680–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JY, Kim DH, Kim DS, Kim JH, Jeong SY, Jeon HB, Lee EH, Yang YS, Oh W. and Chang JW. (2010). Galectin-3 secreted by human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduces amyloid-beta42 neurotoxicity in vitro. FEBS Lett 584:3601–3608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JY, Kim DH, Kim JH, Yang YS, Oh W, Lee EH. and Chang JW. (2012). Umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells protect amyloid-beta42 neurotoxicity via paracrine. World J Stem Cells 4:110–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HJ, Lee JK, Lee H, Shin JW, Carter JE, Sakamoto T, Jin HK. and Bae JS. (2010). The therapeutic potential of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett 481:30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HJ, Lee JK, Lee H, Carter JE, Chang JW, Oh W, Yang YS, Suh JG, Lee BH, Jin HK. and Bae JS. (2012). Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve neuropathology and cognitive impairment in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model through modulation of neuroinflammation. Neurobiol Aging 33:588–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh W, Kim DS, Yang YS. and Lee JK. (2008). Immunological properties of umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Cell Immunol 251:116–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seo SW, Lee J, II, Kim CH, Chang JW, Roh JH, Oh W, Yang YS, Lee K, Kim ST. and Na DL. (2013). A phase I trial of parenchymal injection of umbilical cord stem cells in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimer's Assoc 9:291 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang SE, Ha CW, Jung M, Jin HJ, Lee M, Song H, Choi S, Oh W. and Yang YS. (2004). Mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells developed in cultures from UC blood. Cytotherapy 6:476–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker TL. and Kempermann G. (2014). One mouse, two cultures: isolation and culture of adult neural stem cells from the two neurogenic zones of individual mice. J Vis Exp e51225 DOI: 10.3791/51225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim H, Kim HY, Choi MR, Hwang S, Nam KH, Kim HC, Han JS, Kim KS, Yoon HS. and Kim SH. (2010). Dose-dependent efficacy of ALS-human mesenchymal stem cells transplantation into cisterna magna in SOD1-G93A ALS mice. Neurosci Lett 468:190–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SH. and Ryan TA. (2009). Synaptic vesicle recycling at CNS snapses without AP-2. J Neurosci 29:3865–3874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HS, Shin TH, Lee BC, Yu KR, Seo Y, Lee S, Seo MS, Hong IS, Choi SW, et al. (2013). Human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells reduce colitis in mice by activating NOD2 signaling to COX2. Gastroenterology 145:1392–1403.e1–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eliopoulos N, Stagg J, Lejeune L, Pommey S. and Galipeau J. (2005). Allogeneic marrow stromal cells are immune rejected by MHC class I- and class II-mismatched recipient mice. Blood 106:4057–4065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin MD, Ryan AE, Alagesan S, Lohan P, Treacy O. and Ritter T. (2013). Anti-donor immune responses elicited by allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells: what have we learned so far? Immunol Cell Biol 91:40–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camp DM, Loeffler DA, Farrah DM, Borneman JN. and LeWitt PA. (2009). Cellular immune response to intrastriatally implanted allogeneic bone marrow stromal cells in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J Neuroinflammation 6:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braak H, Braak E. and Bohl J. (1993). Staging of Alzheimer-related cortical destruction. Eur Neurol 33:403–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferri AL, Cavallaro M, Braida D, Di Cristofano A, Canta A, Vezzani A, Ottolenghi S, Pandolfi PP, Sala M, DeBiasi S. and Nicolis SK. (2004). Sox2 deficiency causes neurodegeneration and impaired neurogenesis in the adult mouse brain. Development 131:3805–3819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurki P, Vanderlaan M, Dolbeare F, Gray J. and Tan EM. (1986). Expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)/cyclin during the cell cycle. Exp Cell Res 166:209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francis F, Koulakoff A, Boucher D, Chafey P, Schaar B, Vinet MC, Friocourt G, McDonnell N, Reiner O, et al. (1999). Doublecortin is a developmentally regulated, microtubule-associated protein expressed in migrating and differentiating neurons. Neuron 23:247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munoz JR, Stoutenger BR, Robinson AP, Spees JL. and Prockop DJ. (2005). Human stem/progenitor cells from bone marrow promote neurogenesis of endogenous neural stem cells in the hippocampus of mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:18171–18176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomez-Gaviro MV, Scott CE, Sesay AK, Matheu A, Booth S, Galichet C. and Lovell-Badge R. (2012). Betacellulin promotes cell proliferation in the neural stem cell niche and stimulates neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:1317–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mignone JL, Kukekov V, Chiang AS, Steindler D. and Enikolopov G. (2004). Neural stem and progenitor cells in nestin-GFP transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol 469:311–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramaniam S, Strelau J. and Unsicker K. (2003). Growth differentiation factor-15 prevents low potassium-induced cell death of cerebellar granule neurons by differential regulation of Akt and ERK pathways. J Biol Chem 278:8904–8912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strelau J, Bottner M, Lingor P, Suter-Crazzolara C, Galter D, Jaszai J, Sullivan A, Schober A, Krieglstein K. and Unsicker K. (2000). GDF-15/MIC-1 a novel member of the TGF-beta superfamily. J Neural Transm Suppl 273–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strelau J, Sullivan A, Bottner M, Lingor P, Falkenstein E, Suter-Crazzolara C, Galter D, Jaszai J, Krieglstein K. and Unsicker K. (2000). Growth/differentiation factor-15/macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 is a novel trophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vivo. J Neurosci 20:8597–8603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrillo-Garcia C, Prochnow S, Simeonova IK, Strelau J, Holzl-Wenig G, Mandl C, Unsicker K, von Bohlen Und Halbach O. and Ciccolini F. (2014). Growth/differentiation factor 15 promotes EGFR signalling, and regulates proliferation and migration in the hippocampus of neonatal and young adult mice. Development 141:773–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lassmann H, Weiler R, Fischer P, Bancher C, Jellinger K, Floor E, Danielczyk W, Seitelberger F. and Winkler H. (1992). Synaptic pathology in Alzheimer's disease: immunological data for markers of synaptic and large dense-core vesicles. Neuroscience 46:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sze CI, Troncoso JC, Kawas C, Mouton P, Price DL. and Martin LJ. (1997). Loss of the presynaptic vesicle protein synaptophysin in hippocampus correlates with cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 56:933–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin TF. (2000). Racing lipid rafts for synaptic-vesicle formation. Nat Cell Biol 2:E9–E11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otto H, Hanson PI. and Jahn R. (1997). Assembly and disassembly of a ternary complex of synaptobrevin, syntaxin, and SNAP-25 in the membrane of synaptic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:6197–6201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett MK, Calakos N. and Scheller RH. (1992). Syntaxin: a synaptic protein implicated in docking of synaptic vesicles at presynaptic active zones. Science 257:255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balaji J. and Ryan TA. (2007). Single-vesicle imaging reveals that synaptic vesicle exocytosis and endocytosis are coupled by a single stochastic mode. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:20576–20581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donega V, van Velthoven CT, Nijboer CH, Kavelaars A. and Heijnen CJ. (2013). The endogenous regenerative capacity of the damaged newborn brain: boosting neurogenesis with mesenchymal stem cell treatment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33:625–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coquery N, Blesch A, Stroh A, Fernandez-Klett F, Klein J, Winter C. and Priller J. (2012). Intrahippocampal transplantation of mesenchymal stromal cells promotes neuroplasticity. Cytotherapy 14:1041–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bottner M, Laaff M, Schechinger B, Rappold G, Unsicker K. and Suter-Crazzolara C. (1999). Characterization of the rat, mouse, and human genes of growth/differentiation factor-15/macrophage inhibiting cytokine-1 (GDF-15/MIC-1). Gene 237:105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bottner M, Suter-Crazzolara C, Schober A. and Unsicker K. (1999). Expression of a novel member of the TGF-beta superfamily, growth/differentiation factor-15/macrophage-inhibiting cytokine-1 (GDF-15/MIC-1) in adult rat tissues. Cell Tissue Res 297:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strelau J, Strzelczyk A, Rusu P, Bendner G, Wiese S, Diella F, Altick AL, von Bartheld CS, Klein R, Sendtner M. and Unsicker K. (2009). Progressive postnatal motoneuron loss in mice lacking GDF-15. J Neurosci 29:13640–13648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emsley JG, Mitchell BD, Kempermann G. and Macklis JD. (2005). Adult neurogenesis and repair of the adult CNS with neural progenitors, precursors, and stem cells. Prog Neurobiol 75:321–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim S, Chang KA, Kim J, Park HG, Ra JC, Kim HS. and Suh YH. (2012). The preventive and therapeutic effects of intravenous human adipose-derived stem cells in Alzheimer's disease mice. PLoS One 7:e45757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim JY, Jeong CH, Jun JA, Kim SM, Ryu CH, Hou Y, Oh W, Chang JW. and Jeun SS. (2011). Therapeutic effects of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells after intrathecal administration by lumbar puncture in a rat model of cerebral ischemia. Stem Cell Res Ther 2:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiao H, Guan F, Yang B, Li J, Shan H, Song L, Hu X. and Du Y. (2011). Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit C6 glioma via downregulation of cyclin D1. Neurol India 59:241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guan YM, Zhu Y, Liu XC, Huang HL, Wang ZW, Liu B, Zhu YZ. and Wang QS. (2014). Effect of human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on neuronal metabolites in ischemic rabbits. BMC Neurosci 15:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee M, Jeong SY, Ha J, Kim M, Jin HJ, Kwon SJ, Chang JW, Choi SJ, Oh W, et al. (2014). Low immunogenicity of allogeneic human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 446:983–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jang YK, Kim M, Lee YH, Oh W, Yang YS. and Choi SJ. (2014). Optimization of the therapeutic efficacy of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stromal cells in an NSG mouse xenograft model of graft-versus-host disease. Cytotherapy 16:298–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim DS, Kim JH, Lee JK, Choi SJ, Kim JS, Jeun SS, Oh W, Yang YS. and Chang JW. (2009). Overexpression of CXC chemokine receptors is required for the superior glioma-tracking property of umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 18:511–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim SM, Oh JH, Park SA, Ryu CH, Lim JY, Kim DS, Chang JW, Oh W. and Jeun SS. (2010). Irradiation enhances the tumor tropism and therapeutic potential of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-secreting human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in glioma therapy. Stem Cells 28:2217–2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.