Background: Skeletal muscle-specific Fyn transgenic mice show severe muscle wasting phenotype concomitant with increased mTORC1 activity.

Results: Overexpression of Fyn stimulates mTORC1 and IRE1α phosphorylation, and rapamycin treatment represses Fyn- and ER stress-induced cell death.

Conclusion: Fyn plays a role in ER stress-induced cell death at least partially through regulation of mTORC1.

Significance: Our findings indicate that Fyn drives pro-apoptotic signaling by activating the unfolded protein response.

Keywords: c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), cell death, endoplasmic reticulum stress (ER stress), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), skeletal muscle, Fyn, IRE1α

Abstract

We previously reported that the skeletal muscle-specific overexpression of Fyn in mice resulted in a severe muscle wasting phenotype despite the activation of mTORC1 signaling. To investigate the bases for the loss of muscle fiber mass, we examined the relationship between Fyn activation of mTORC1, JNK, and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Overexpression of Fyn in skeletal muscle in vivo and in HEK293T cells in culture resulted in the activation of IRE1α and JNK, leading to increased cell death. Fyn synergized with the general endoplasmic reticulum stress inducer thapsigargin, resulting in the activation of IRE1α and further accelerated cell death. Moreover, inhibition of mTORC1 with rapamycin suppressed IRE1α activation and JNK phosphorylation, resulting in protecting cells against Fyn- and thapsigargin-induced cell death. Moreover, rapamycin treatment in vivo reduced the skeletal muscle IRE1α activation in the Fyn-overexpressing transgenic mice. Together, these data demonstrate the presence of a Fyn-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress that occurred, at least in part, through the activation of mTORC1, as well as subsequent activation of the IRE1α-JNK pathway driving cell death.

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 is responsible for the folding, maturation, and trafficking of most secretory and membrane proteins, as well as for autophagosome biogenesis, gluconeogenesis, and lipid synthesis (1). ER stress happens when the nascent protein loading exceeds the ER folding capacity under circumstances such as virus infection, gene mutation, calcium flux perturbation, or glucose deprivation, and it has been linked with diseases such as cancer, neurodegeneration, inflammation, metabolism, aging, and muscle dysfunction (2, 3). ER stress activates the unfolded protein response (UPR) to suppress general protein synthesis and increase the ER folding capacity and misfolded protein degradation, thereby restoring the cell back to homeostasis. However, if the stress response is prolonged or beyond the adaptive range, UPR may also lead to cell death (1).

The UPR is mediated by three pathways, RNA-dependent protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) (4, 5). PERK is an ER-resident type I transmembrane protein kinase. PERK phosphorylation at Ser-51 of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) in general inhibits cap-dependent protein translation with the notable exception of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). As a transcription factor, ATF4 expression is activated by phosphorylation of eIF2α, which in turn promotes the transcription of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP), which is important in ER stress-induced apoptosis by regulating calcium signaling and cytochrome c release from mitochondria (6). Initially located at the ER as a type II transmembrane protein, ATF6 is transferred to the Golgi, where it goes through cleavage by site-1 protease and site-2 protease. The cleaved N-terminal ATF6 fragment enters the nucleus and increases the transcription of adaptive chaperons, such as Bip. IRE1 is a type I transmembrane protein with both endoribonuclease and kinase activity. IRE1α is ubiquitously expressed, whereas the other isoform, IRE1β, is found only in the epithelial cells of gastrointestinal track (7) and airway (8). The endoribonuclease activity of IRE1α cleaves a 26-nucleotide intron from X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) to generate spliced XBP1 (XBP1s), a potent transcription factor that participates in pro-survival response but that declines during prolonged progression of ER stress (9). IRE1α also forms a complex with the adaptor protein TNFR-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) to activate apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) and JNK (10). The activation of JNK is considered to be pro-apoptotic as it phosphorylates different members of the Bcl-2 family and shifts the balance toward cell death (6).

Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) (previously termed mammalian target of rapamycin) is a master manipulator of cell growth and metabolism. This atypical serine/threonine protein kinase is the core of two distinct multi-protein complexes, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2), which share common core subunits that include mTOR, mammalian lethal with sec-13 (mLST8), DEP domain containing mTOR-interacting protein (DEPTOR), and the Tti1-Tel2 complex (11). In addition, the mTORC1 complex also contains the regulatory-associated protein of mammalian target of rapamycin (Raptor) and proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa (PRAS40), whereas the mTORC2 complex contains the rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (Rictor), mammalian stress-activated map kinase-interacting protein 1 (mSin1), and protein observed with Rictor 1 and 2 (protor1/2) (11). mTORC1 enhances protein synthesis through direct phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1) and p70 S6 kinase (S6K), and ribosomal protein S6 is a downstream target of S6K (12).

Fyn is a ubiquitously expressed non-receptor tyrosine kinase of the Src family (13). Two intramolecular interactions, SH3-linker and SH2-phosphorylated tyrosine (SH2-pY) tail, maintain Fyn in a closed inactive conformation (14). Although Fyn functions in B cell expansion and maturation (15, 16) and tumor progression and metastasis (17), it also regulates fatty acid oxidation through direct phosphorylation of liver kinase B 1 (LKB1) and inactivation of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (18–20). In turn, inhibited AMPK dampens its function in phosphorylating Raptor and tuberous sclerosis proteins 1 and 2 complex (TSC1/2 complex, the upstream Rheb GTPase-activating protein) to suppress mTORC1 activation (21).

Thapsigargin (TG) induces ER stress through ER calcium depletion by ER calcium ATPase blockage (22). It was reported that mTORC1 was activated under ER stress conditions and that its activation led to cell death via IRE1α-JNK pathway (23). Consistently, TSC1- or TSC2-deficient cells showed increased phosphorylation of S6, IRE1α, and JNK and were sensitive to ER stress-induced apoptosis, which was inhibited by rapamycin treatment (24).

We previously reported that Fyn deficiency activates fatty acid oxidation with improved glucose homeostasis in whole body Fyn knock-out mice (25) and that Fyn overexpression activates mTORC1 through inhibition of the LKB1-AMPK pathway (18, 26). Moreover, skeletal muscle-specific Fyn transgenic mice (SKM-Fyn) displayed a marked phenotype of muscle wasting (26). Based upon these findings, we speculated that Fyn functions as an inducer of ER stress through the indirect activation of mTORC1, and the consequent activation of IRE1α pathway and cell death can at least partially explain the muscle wasting in SKM-Fyn mice. In the present study, we demonstrate that both in transfected cells in culture and in transgenic mice, Fyn overexpression activates mTORC1 with the concomitant activation of IRE1α-JNK pathway, which potentiates the ER stress-induced cell death.

Experimental Procedures

Antibodies and Reagents

The phospho-IRE1α antibody was purchased from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Antibodies for detecting GAPDH and V5 were purchased from Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, MA), and all the other antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA). Hoechst was purchased from Life Technologies. Propidium iodide, thapsigargin, and tunicamycin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Rapamycin for in vitro experiments was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and rapamycin for in vivo injection was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). JNK inhibitor was purchased from Calbiochem.

Fyn Transgenic Mice

The skeletal muscle-specific FynB transgenic and littermate control mice were generated as described previously and maintained on a C57BL6/129svj background (26). The mice were fed ad libitum with chow diet containing 20% protein and 9% fat (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20, catalog number 5058). All animal studies were approved by and performed following the guidelines from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Cell Culture

HEK293T cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a moisturized incubator with 5% CO2. Cell transfection was performed using the FuGENE HD transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Fitchburg, WI). Plasmids of pcDNA, pcDNA-Fyn-WT-V5, and pcDNA-Fyn-KD-V5 were constructed before (26).

Hoechst, Propidium Iodide, and TUNEL Analysis

Hoechst reagent and propidium iodide at 4 and 1 μg/ml were applied to the cells grown in 6-well plates followed by incubation at 37 °C for 5–10 min. The incorporation of label was determined by fluorescent light microscopy. TUNEL assay was applied to the cells grown on coverslips after 4% paraformaldehyde fixation, followed by using the ApopTag® fluorescein in situ apoptosis detection kit as described by the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Microscopic Analysis

The live cells were directly observed in 6-well plates under transmitted light microscopy using a Zeiss Axiovert 40c microscope with a 10× A plan 0.25 objective, equipped with a Canon PowerShot A640 digital camera. Fluorescent images for Hoechst and propidium iodide and corresponding translight images were obtained from live cells using an Olympus 1X71 inverted microscope with a LUCPlanFLN 10× 0.30 or 20× 0.45 objective and exported by Olympus DP2-BSW application software. Fluorescent images of TUNEL staining were obtained using a Leica SP5 AOBS confocal microscope with a 63× 1.4 oil objective and exported by the Leica LAS-AF software. All images were captured at room temperature.

Immunoblotting

Cell and tissue extracts were prepared in lysis buffer as described by Cao et al. (27) containing protease inhibitor cocktail set V (Calbiochem) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Total lysates were separated in 8 or 15% SDS-PAGE overnight or semidry transferred to PVDF membranes at 4 °C and soaked in blocking buffer (GenDEPOT, Barker, TX) for 2 h at room temperature. The incubation of primary antibodies proceeded at 4 °C overnight, and the incubation of secondary antibodies (Thermo Scientific and LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) proceeded at room temperature for 30 min before development using ECL or the Odyssey infrared imaging system (9140-01 Odyssey® CLx infrared imaging system, LI-COR Biosciences).

Semi-quantitative and Real-time Quantitative PCR

The RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used to isolate total RNA from cells or tissues. cDNA was generated by reverse transcription using a SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) and served as a template for semi-quantitative and quantitative PCR. Semi-quantitative PCR for detecting XBP1 splicing was performed by using the GoTaq Green master mix (Promega) on a T1000TM thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences for XBP1 and PCR condition were described previously (9), and GAPDH was amplified as internal control together with the following primers: forward, 5′-ACC ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC AC-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCC ACC ACC CTG TTG CTG TA-3′. PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on a 2.5% agarose (Bio-Rad)/Tris-acetate-EDTA gel. Real-time quantitative PCR reactions were run on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system with a 384-well block module (Life Technologies). Gene expression of Bip, Chop, Fyn, and GAPDH was amplified by using TaqMan gene expression assays with the ΔΔCt method for quantification (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ). Spliced XBP1 was amplified by the Integrated DNA Technologies PrimeTime quantitative PCR assay (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) as described previously (28, 29). GAPDH was amplified in each experiment and served as the endogenous internal control.

Generation of Stable Knockdown Cell Lines

The stable cell line with endogenous IRE1α knockdown was achieved by lentivirus infection using a pLKO.1 vector containing IRE1α-targeting shRNA (TRCN0000000530). Control cells were infected by lentivirus containing the empty vector (pLKO.1). Virus generation and cell infection were performed following the protocol from Addgene. Puromycin (2.5 μg/ml) was applied after 24 h of infection for cell selection of positive infection.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

The numbers of the fluorescent puncta from microscopy analysis were counted by using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). All the results present were representatives from at least three repeats, and quantified data were present as mean ± S.E. Significant data were defined as p < 0.05 using analysis of variance followed by the Tukey's multiple comparison or Student's t test.

Results

Fyn Overexpression in Skeletal Muscle Increases ER Stress

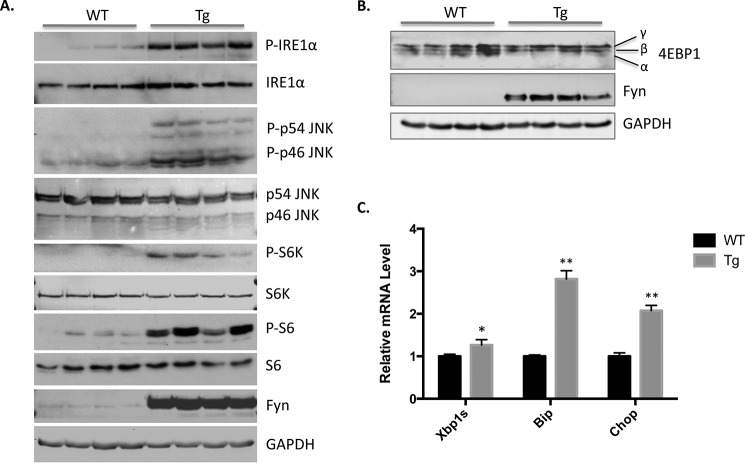

Previously, we observed that transgenic mice overexpressing Fyn in skeletal muscle resulted in a marked increase of mTORC1 activation (26), which is important in regulation of ER stress-induced cell death (23, 24). To investigate the correlation between Fyn- and ER stress-induced cell death, in which the latter could be responsible for the muscle wasting phenotype of SKM-Fyn mice, we examined the effect of Fyn on the indicative markers of three UPR pathways. The Western blot analyses of SKM-Fyn mice demonstrated a marked increase in IRE1α phosphorylation (Fig. 1A). The increased IRE1α phosphorylation was associated with the increase in XBP1 splicing and JNK phosphorylation (Fig. 1, A and C). In parallel, the downstream targets of ATF6 and PERK stimulation (Bip and Chop mRNA, respectively) were also elevated, indicating that all three arms of the UPR were activated (Fig. 1C). Thr-389 is the mTORC1-specific site of S6K phosphorylation, which is the major event promoting S6K activation (30). Consistent with our previous results, Fyn overexpression also led to the mTORC1 activation (26), shown by the increased phosphorylation of S6K at Thr-389 and its downstream S6 phosphorylation (Fig. 1A). 4EBP1 is another direct mTORC1 substrate that is phosphorylated on multiple sites, represented by three bands (α, β, γ) in SDS-polyacrylamide gels (31, 32). In accordance with increased S6K phosphorylation, SKM-Fyn transgenic mice also demonstrated increased β and γ bands with decreased α band indicative of mTORC1 activation (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Skeletal muscle-specific Fyn overexpression induces mTORC1 and IRE1α activation. Wild type (WT) and SKM-Fyn mice (Tg) at 3 weeks of age were sacrificed after an overnight fast. A and B, gastrocnemius muscles were isolated, and cell extracts were prepared for Western blotting against the proteins indicated. These are representative immunoblots independently performed three times. p indicates phosphorylated form. C, the total RNA was extracted from isolated gastrocnemius muscles. The mRNA levels of XBP1s, Bip, and Chop were determined by quantitative PCR. The data are presented as mean ± S.E. from four independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Fyn Overexpression Activates mTORC1 and IRE1α in HEK293T Cells in Culture

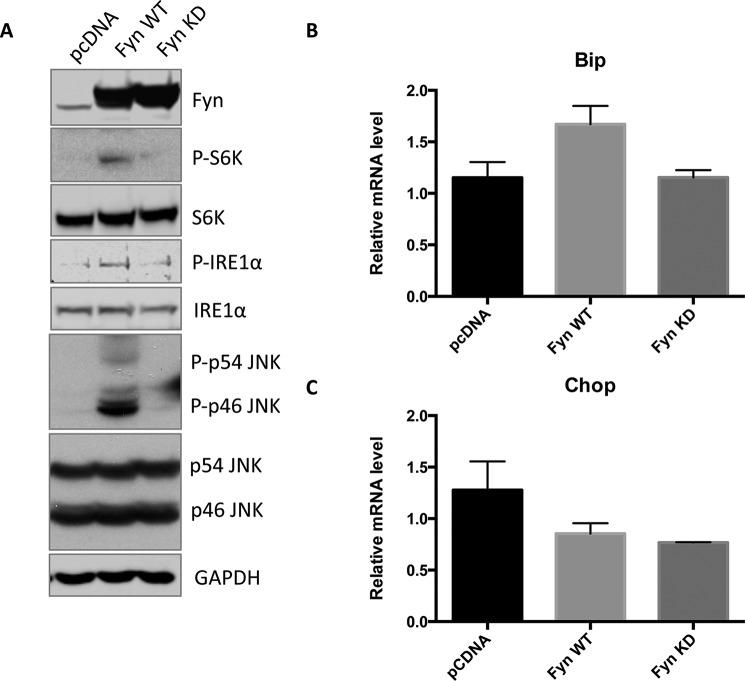

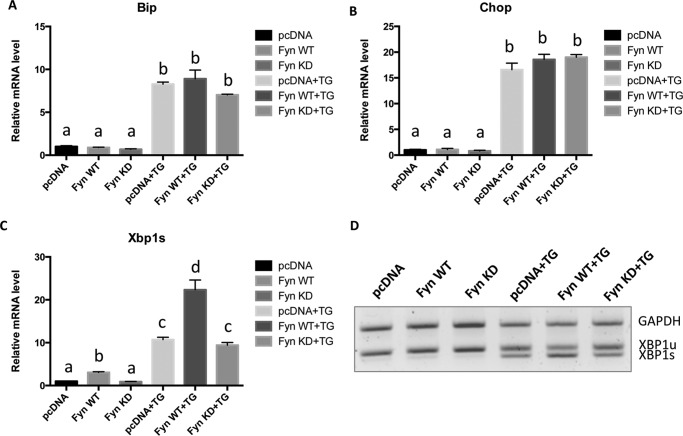

To examine the role of Fyn in mediating ER stress in a more experimentally tractable system, we transfected wild type Fyn (Fyn WT) and a kinase-defective Fyn mutant (Fyn KD) in HEK293T cells. Expression of Fyn WT increased IRE1α and JNK phosphorylation as well as that of the mTORC1 substrate S6K (Fig. 2A). In contrast, expression of Fyn KD had no significant effect (Fig. 2A). Neither expression of Fyn WT nor expression of Fyn KD had any statistically significant effect on Bip or Chop mRNA levels (Fig. 2, B and C). These data indicate that the effect of Fyn overexpression on IRE1α phosphorylation in mice is recapitulated in acute Fyn-transfected HEK293T cells. However, the lack of effect on Bip or Chop probably reflects the additional presence of ER stress inducers in vivo that are not present in tissue culture. To address this possibility, HEK293T cells were transfected with and without the Fyn and subsequently treated with TG, a well established ER stress inducer (33). As expected, TG induced both Bip and Chop mRNA that were not further increased by the expression of Fyn WT or Fyn KD (Fig. 3, A and B). Although TG treatment also increased XBP1 splicing, this response was further enhanced by the expression of Fyn WT (Fig. 3, C and D). These data indicate that Fyn regulates the IRE1α signaling pathway of UPR.

FIGURE 2.

Fyn activates mTORC1, IRE1α, and JNK in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with the empty vector (pcDNA), Fyn wild type (Fyn WT), or Fyn kinase-defective (Fyn KD). A, forty-eight hours after transfection, cell extracts were prepared and subjected to Western blot for the indicated proteins. These are representative immunoblots independently performed three times. p indicates phosphorylated form. B, RNA was prepared, and the levels of Bip and Chop mRNA were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. These data are presented as mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments.

FIGURE 3.

TG increases Fyn induction of XBP1s but not Bip or Chop mRNA expression in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with the empty vector (pcDNA), Fyn wild type (Fyn WT), or Fyn kinase-defective (Fyn KD). Forty-eight hours later, the cells were treated with 1 μm TG for 4 h. A–C, the levels of Bip (A), Chop (B), and spliced XBP1 (XBP1s) (C) mRNA were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. D, the mRNA levels of unspliced XBP1 (XBP1u) and spliced XBP1 (XBP1s) were analyzed by semi-quantitative PCR. These data are presented as mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. Non-identical letters (a, b, c, and d) indicate results that are statistically different from each other at p < 0.05.

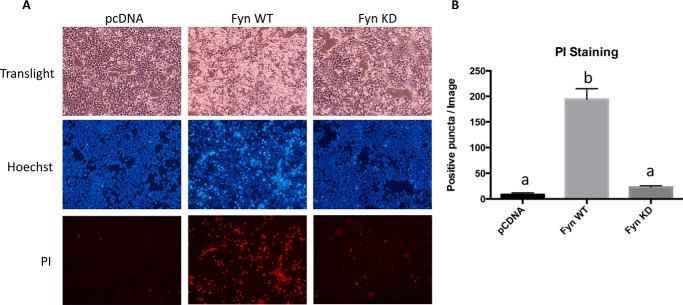

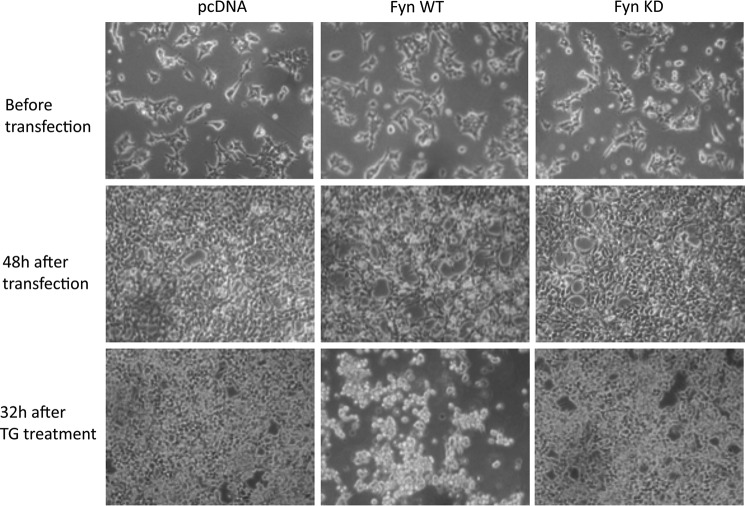

Fyn Overexpression Induces Cell Death in HEK293T Cells in Culture through IRE1α-JNK Pathway

As visually apparent, acute expression of Fyn resulted in significant morphological changes that include cell shrinkage, increased rounding, and reduced adherence to the substratum (Fig. 4A). In contrast, expression of Fyn KD had no significant morphological features when compared with empty vector control-transfected cells. To assess whether the Fyn WT-induced morphology was associated with cell death, the cells were treated with Hoechst to visualize condensed nuclei and propidium iodide (PI) to assess cell permeability. Hoechst staining demonstrated a large increase in condensed nuclei cells, and PI demonstrated a large increase in permeable cells following acute Fyn WT transfection. Quantification of the PI staining is shown in Fig. 4B. The Fyn WT- but not Fyn KD-induced cell death was further confirmed by TUNEL staining (Fig. 5, A and B).

FIGURE 4.

Overexpression of active Fyn kinase in HEK293T cells increases Hoechst and propidium iodide staining. HEK293T cells were transfected with the empty vector (pcDNA), Fyn wild type (Fyn WT), or Fyn kinase-defective (Fyn KD). A, forty-eight hours later, the cells were subjected to Hoechst and PI staining. These are representative images from experiments independently performed three times. B, the numbers of positive PI-stained cells were quantified from 10 images. These data are presented as mean ± S.E. Non-identical letters (a and b) indicate results that are statistically different from each other at p < 0.01.

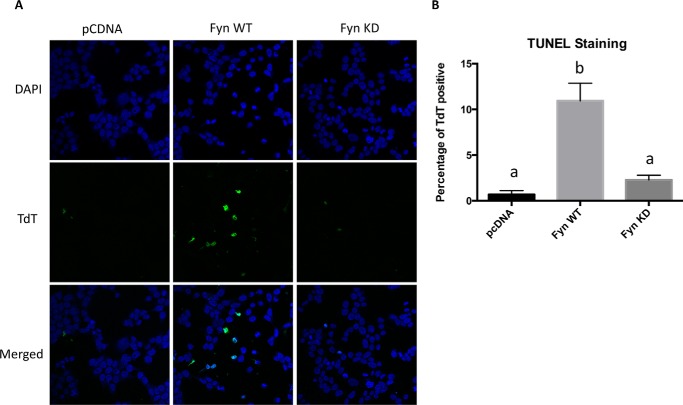

FIGURE 5.

Overexpression of active Fyn kinase in HEK293T cells increases TUNEL staining. HEK293T cells were transfected with the empty vector (pcDNA), Fyn wild type (Fyn WT), or Fyn kinase-defective (Fyn KD). A, forty-eight hours later, the cells were subjected to TUNEL staining. These are representative images from experiments independently performed three times. DAPI was pseudocolored as blue, whereas terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (TdT) was pseudocolored as green. B, the percentage of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (TdT)-positive cells was quantified from 10 images. These data are presented as mean ± S.E. Non-identical letters (a and b) indicate results that are statistically different from each other at p < 0.01.

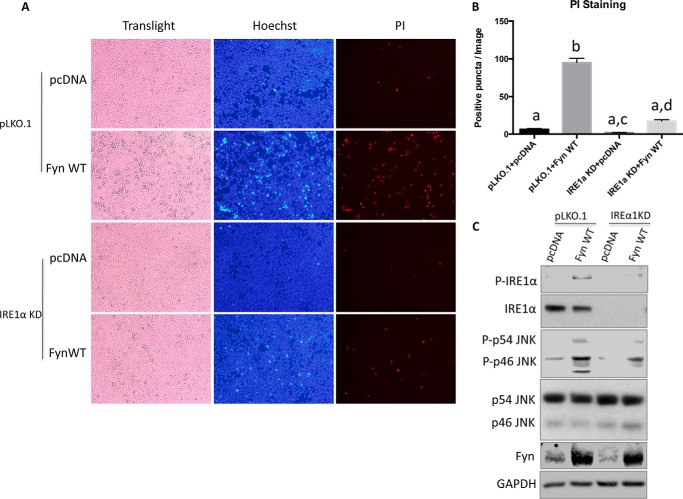

To assess the IRE1α dependence of Fyn-induced cell death, we generated a stable cell line with IRE1α deficiency by infection with a lentivirus shRNA and a control cell line infected with the empty lentiviral vector (pLKO.1). PI staining demonstrated a lower degree of Fyn-induced cell death in the IRE1α knockdown cells (Fig. 6, A and B).

FIGURE 6.

Knockdown of endogenous IRE1α in HEK293T cells suppresses the Fyn overexpression-induced cell death. Cells of IRE1α knockdown (IRE1α KD) and control cells (pLKO.1) were transfected by empty vector (pcDNA) or Fyn wild type (Fyn WT). A, forty-eight hours later, the cells were subjected to Hoechst and PI staining. These are representative images from experiments independently performed three times. B, the numbers of positive PI-stained cells were quantified from 10 images. These data are presented as mean ± S.E. Non-identical letters (a, b, and c) indicate results that are statistically different from each other at p < 0.05. C, cell extracts were prepared and subjected to Western blot for detection of the indicated proteins. p indicates phosphorylated form. These data are representatives of three independent experiments.

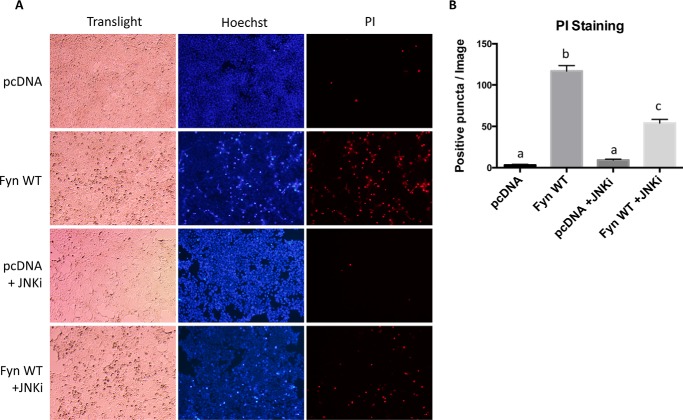

JNK phosphorylation is a downstream consequence of IRE1α activation leading to cell death through phosphorylation of Bcl-2 family members (6). Consistent with the IRE1α dependence of JNK phosphorylation, knockdown of IREα1 reduced the extent of JNK phosphorylation that occurs in Fyn-overexpressing cells (Fig. 6C). Treatment of Fyn-transfected cells with a JNK inhibitor resulted in fewer condensed nuclei and PI-positive stained cells (Fig. 7, A and B). Together these data indicate that the Fyn-induced cell death occurs at least partially through activation of the IRE1α-JNK pathway.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of JNK represses the Fyn overexpression-induced cell death in HEK293T cells. Cells were transfected by empty vector (pcDNA) and Fyn wild type (Fyn WT). A, thirty-two hours after transfection, the cells were treated with or without JNK inhibitor (JNKi, 25 μm) for 16 h before being subjected to Hoechst and PI staining. These are representative images from experiments independently performed three times. B, the numbers of positive PI-stained cells were quantified from 10 images. The data are presented as mean ± S.E. Non-identical letters (a, b, and c) indicate results that are statistically different from each other at p < 0.05.

Thapsigargin Potentiates Cell Death Induced by Fyn Overexpression

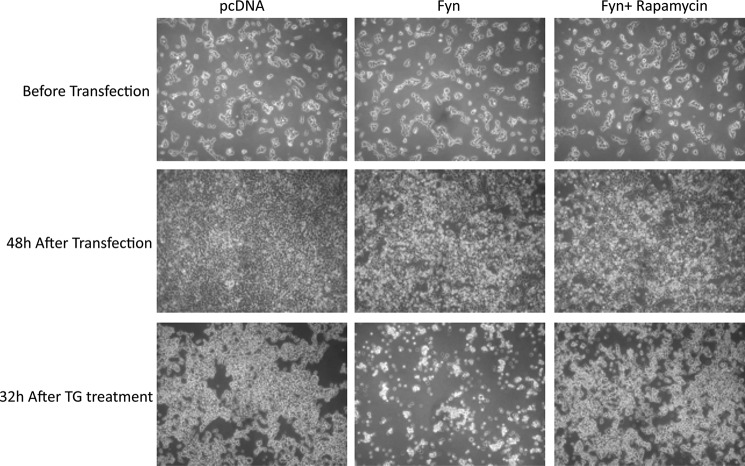

To examine the effects of general ER stress with Fyn, we next examined cell death by TG in cells overexpressing Fyn. As observed previously, following transfection with Fyn WT but not Fyn KD, there were obvious visual morphological changes indicative of cell death initiation (Fig. 8). Treatment of control cells with TG also induced some morphological changes that were not as visually apparent when compared with that observed in the Fyn WT-transfected cells. In any case, the combination of TG treatment in cells overexpressing Fyn WT displayed a large increase in cell detachment with the remaining cells highly rounded, indicative of cell death.

FIGURE 8.

Fyn potentiates TG-induced cell death in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with the empty vector (pcDNA), Fyn wild type (Fyn WT), or Fyn kinase-defective (Fyn KD). Forty-eight hours later, the cells were treated with 1 μm TG for 32 h. Representative transmitted light microscopy images from three independent experiments are presented.

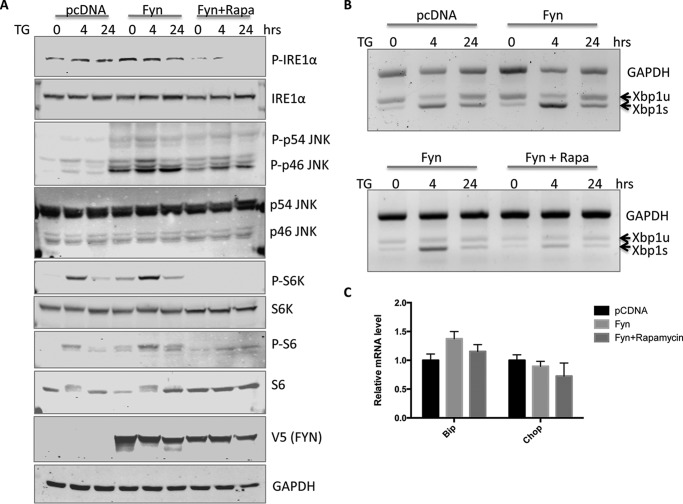

As observed previously, expression of Fyn WT increased IRE1α and JNK phosphorylation along with increased phosphorylation of the mTORC1 downstream targets, S6K and S6 (Fig. 9A). Although TG treatment also activated these pathways, it was not as strong as Fyn WT and was further potentiated in the cells overexpressing Fyn WT treated with TG. Similarly, TG induced XBP1 splicing that was enhanced in cells overexpressing Fyn WT (Fig. 9B). Previous studies have reported that inhibition of mTORC1 with rapamycin can suppress the ER stress response (23, 24). Consistent with these studies, we also observed that rapamycin suppressed the phosphorylation of IRE1α and JNK as well as the expected mTORC1 target substrates (Fig. 9A). The inhibition of IRE1α activation was also observed by the inhibition of XBP1 splicing (Fig. 9B). However, rapamycin did not significantly inhibit the induction of Bip and Chop mRNA, further supporting a specific effect of Fyn on the IRE1α pathway through the activation of mTORC1 (Fig. 9C).

FIGURE 9.

Fyn potentiates TG-induced mTORC1-IRE1α activation in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with either the empty vector (pcDNA) or Fyn wild type (Fyn). Forty-eight hours later, the cells were treated with 1 μm TG with or without 100 nm rapamycin (Rapa) for the indicated times. A, cell extracts were prepared and subjected to Western blotting against the proteins indicated. These are representative immunoblots independently performed three times. p indicates phosphorylated form. B, RNA was isolated, and mRNA levels of unspliced XBP1 (XBP1u) and spliced XBP1 (XBP1s) were analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. These are representative PCR reactions independently performed three times. C, the levels of Bip and Chop mRNA in cells treated with TG with or without rapamycin for 4 h were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. The data are presented as mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments.

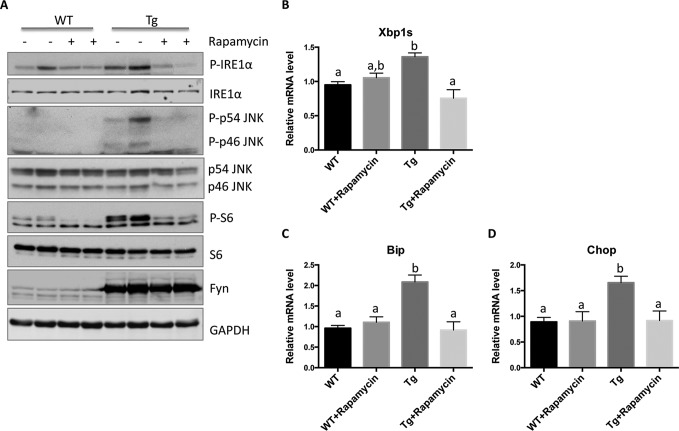

As shown in Fig. 8, thapsigargin treatment of Fyn WT-transfected cells resulted in a substantial detachment of cells characteristic of cell death. However, rapamycin treatment completely protected against the Fyn WT-induced loss of cells (Fig. 10). Moreover, rapamycin treatment of the SKM-Fyn transgenic mice in vivo not only inhibited the Fyn-induced activation of mTORC1 (S6 phosphorylation) but also suppressed IRE1α and JNK phosphorylation (Fig. 11A) and resulted in a concomitant decrease of XBP1s, Bip, and Chop mRNA levels (Fig. 11, B–D). These data are consistent with a Fyn-induced activation of mTORC1 that drives ER stress-induced cell death, at least partially through IRE1α.

FIGURE 10.

Rapamycin protects against Fyn and thapsigargin-induced cell death in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with either the empty vector (pcDNA) or Fyn wild type (Fyn). Forty-eight hours later, the cells were treated with 1 μm TG with or without 100 nm rapamycin for 32 h. Representative transmitted light microscopy images are presented from three independent experiments.

FIGURE 11.

Rapamycin suppresses mTORC1, IRE1α, and JNK activation in SKM-Fyn mice. Three-week-old wild type (WT) and SKM-Fyn transgenic (Tg) mice were intraperitoneally injected with vehicle or rapamycin (2 mg/kg) once a day for 4 days. The mice were then fasted overnight, and gastrocnemius muscles were isolated. A, extracts were prepared and subjected to Western blotting against the proteins indicated. These are representative immunoblots independently performed four times. p indicates phosphorylated form. B–D, extracts were prepared, and the levels of spliced XBP1 (XBP1s), Bip, and Chop mRNA were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. The data are presented as mean ± S.E. from four independent experiments. Non-identical letters (a and b) indicate results that are statistically different from each other at p < 0.05.

Discussion

Skeletal muscle is the largest organ of mammals. It undertakes indispensable functions in locomotion, posture, breathing, and whole body metabolism (34). Calcium signaling profoundly participates in skeletal muscle physiology of contraction and pathology of muscle dystrophy (35, 36), which puts ER, the reservoir of calcium, in a more vital position in skeletal muscle than in other tissues. For example, loss of skeletal muscle mass with decreased strength is a major contributor to frailty that occurs during aging (37), which is correlated with increased ER stress (38). In addition, other muscle wasting pathologies also occur during states of denervation and immobilization (disuse-related atrophy) and in states of cancer cachexia, sepsis, and diabetes (nutrient-related atrophy). Several pathways have been identified as stimulating skeletal muscle wasting in different pathophysiologic conditions including activation of the atrogin E3 ligase responsible for proteasome-mediated degradation, STAT3 activation during cancer cachexia, and inhibition of macroautophagy (26, 39–41). Previously, we observed that skeletal muscle-specific overexpression of Fyn also resulted in severe muscle wasting associated with mTORC1 activation and inhibition of AMPK activation (26). Although Fyn expression also suppressed macroautophagy, the causality relationship between mTORC1 activation and skeletal muscle wasting was not determined.

In this regard, it was shown that the loss of the tuberous sclerosis complex, an upstream inhibitor of mTORC1, induced the ER unfolded response to activate apoptosis (24). As mTORC1 integrates macroautophagy (42) and ER stress signals, we speculated that Fyn activation of mTORC1 would contribute to ER stress induction mediating UPR and skeletal muscle wasting. To test this hypothesis, we examined the ER stress responses in skeletal muscle overexpressing Fyn and observed activation of mTORC1 along with all three branches of the UPR. Moreover, treatment of the SKM-Fyn mice with the specific mTORC1 inhibitor, rapamycin, suppressed UPR. Although Fyn expression in HEK293T cells also induced UPR, in this case, the IRE1α branch was the only one activated. Several groups have observed a role for mTORC1 in activating UPR, and whether this occurs for all three branches or selectively for the IRE1α-JNK pathway is still under debate (23, 43). Nevertheless, mTORC1 activation of UPR has been shown to induce cellular apoptosis (23). In this regard, we also observed a Fyn-dependent induction of cellular apoptosis that was suppressed by rapamycin treatment. Moreover, TG treatment increased UPR and potentiated the Fyn induction of apoptosis that was prevented by rapamycin.

It is well accepted that the IRE1α plays an important role in cell fate determination under ER stress, and IRE1α phosphorylation is required for its activity (44), including XBP1 splicing and JNK phosphorylation (23, 45). Currently, we do not know the basis for the differential effect of Fyn expression on the three UPR branches in skeletal muscle versus cultured HEK293T cells. One difference between these two systems is the timeframe of Fyn expression. In vivo, Fyn was expressed at the beginning of skeletogenesis and remained expressed during embryonic development and into adulthood. In contrast, the HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with Fyn that was expressed for only a few days. Thus, compensational crosstalk between UPR branches may be activated only under chronic or prolonged stress conditions. It is also possible that the effect of Fyn activation of mTORC1, as well as the subsequent UPR activation, occurs in a cell context-dependent manner.

In addition, rapamycin as an effective inhibitor of mTORC1 was only partially effective in inhibiting JNK activation in HEK293T cells. This suggests the presence of an mTORC1-independent pathway responsible for JNK activation. In this regard, the small GTP-binding protein RhoA has also been reported to promote apoptosis via JNK signaling (46).

In any case, JNK is a stress-activated kinase and a downstream target of mTORC1 activation that is associated with insulin resistance (47) and aging (34). JNK activation is also a potent activator of cellular apoptosis (48), and our data demonstrate that Fyn stimulates JNK activation site phosphorylation in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, treatment with a JNK inhibitor partially repressed Fyn-induced cell death in vitro. These findings provide strong evidence that Fyn activates the IRE1α-JNK signaling pathway and that it is the JNK activation that is the proximal event responsible for inducing cell death. Additionally, we have also observed that during aging, the skeletal muscle levels of Fyn protein are increased with increased mTORC1 activation,3 consistent with disrupted ER homeostasis in aged animals (38, 49), suggesting the involvement of a Fyn-mTORC1-IRE1α pathway-induced cell death in sarcopenia (age-related muscle atrophy).

Taken together, these data indicate a novel role for Fyn as an activator of ER stress mediated through IRE1α and JNK activation. As unresolved ER stress and JNK activation are established activators of cellular apoptosis, this can account for the skeletal muscle wasting induced by Fyn expression. Future studies are now needed to molecularly determine the basis for the loss of muscle fiber protein.

Author Contributions

Y. W. and J. E. P. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. Y. W. performed and analyzed the experiments. E. Y. and H. Z. provided technical assistance for the preparation of Figures 1, 3, and 11. E. Y. and H. Z. revised the manuscript critically.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK033823, DK098439, and DK020541 (to J. E. P.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Y. Wang, E. Yamada, H. Zong, and J. E. Pessin, unpublished results.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- PERK

- RNA-dependent protein kinase-like ER kinase

- ATF

- activating transcription factor

- CHOP

- CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein

- IRE1

- inositol-requiring enzyme 1

- XBP1

- X-box-binding protein 1

- mTOR

- mechanistic target of rapamycin

- mTORC1

- mTOR complex 1

- mTORC2

- mTOR complex 2

- S6K

- S6 ribosomal protein kinase

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- TG

- thapsigargin

- TNFR

- TNF receptor

- KD

- kinase-defective

- SH

- Src homology

- PI

- propidium iodide.

References

- 1. Hetz C. (2012) The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sano R., Reed J. C. (2013) ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 3460–3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rayavarapu S., Coley W., Nagaraju K. (2012) Endoplasmic reticulum stress in skeletal muscle homeostasis and disease. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 14, 238–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernales S., Papa F. R., Walter P. (2006) Intracellular signaling by the unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 487–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ron D., Walter P. (2007) Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sovolyova N., Healy S., Samali A., Logue S. E. (2014) Stressed to death: mechanisms of ER stress-induced cell death. Biol. Chem. 395, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bertolotti A., Wang X., Novoa I., Jungreis R., Schlessinger K., Cho J. H., West A. B., Ron D. (2001) Increased sensitivity to dextran sodium sulfate colitis in IRE1β-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 585–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martino M. B., Jones L., Brighton B., Ehre C., Abdulah L., Davis C. W., Ron D., O'Neal W. K., Ribeiro C. M. (2013) The ER stress transducer IRE1β is required for airway epithelial mucin production. Mucosal Immunol. 6, 639–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin J. H., Li H., Yasumura D., Cohen H. R., Zhang C., Panning B., Shokat K. M., Lavail M. M., Walter P. (2007) IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science 318, 944–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nishitoh H., Matsuzawa A., Tobiume K., Saegusa K., Takeda K., Inoue K., Hori S., Kakizuka A., Ichijo H. (2002) ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 16, 1345–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laplante M., Sabatini D. M. (2012) mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149, 274–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCormick M. A., Tsai S. Y., Kennedy B. K. (2011) TOR and ageing: a complex pathway for a complex process. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 366, 17–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Resh M. D. (1998) Fyn, a Src family tyrosine kinase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 30, 1159–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engen J. R., Wales T. E., Hochrein J. M., Meyn M. A., 3rd, Banu Ozkan S., Bahar I., Smithgall T. E. (2008) Structure and dynamic regulation of Src-family kinases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3058–3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rodríguez-Alba J. C., Moreno-García M. E., Sandoval-Montes C., Rosales-Garcia V. H., Santos-Argumedo L. (2008) CD38 induces differentiation of immature transitional 2 B lymphocytes in the spleen. Blood 111, 3644–3652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yasue T., Nishizumi H., Aizawa S., Yamamoto T., Miyake K., Mizoguchi C., Uehara S., Kikuchi Y., Takatsu K. (1997) A critical role of Lyn and Fyn for B cell responses to CD38 ligation and interleukin 5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10307–10312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saito Y. D., Jensen A. R., Salgia R., Posadas E. M. (2010) Fyn: a novel molecular target in cancer. Cancer 116, 1629–1637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamada E., Pessin J. E., Kurland I. J., Schwartz G. J., Bastie C. C. (2010) Fyn-dependent regulation of energy expenditure and body weight is mediated by tyrosine phosphorylation of LKB1. Cell Metab. 11, 113–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Posadas E. M., Al-Ahmadie H., Robinson V. L., Jagadeeswaran R., Otto K., Kasza K. E., Tretiakov M., Siddiqui J., Pienta K. J., Stadler W. M., Rinker-Schaeffer C., Salgia R. (2009) FYN is overexpressed in human prostate cancer. BJU Int. 103, 171–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sakamoto K., McCarthy A., Smith D., Green K. A., Grahame Hardie D., Ashworth A., Alessi D. R. (2005) Deficiency of LKB1 in skeletal muscle prevents AMPK activation and glucose uptake during contraction. EMBO J. 24, 1810–1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sanchez A. M., Candau R. B., Csibi A., Pagano A. F., Raibon A., Bernardi H. (2012) The role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the coordination of skeletal muscle turnover and energy homeostasis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 303, C475–C485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rogers T. B., Inesi G., Wade R., Lederer W. J. (1995) Use of thapsigargin to study Ca2+ homeostasis in cardiac cells. Biosci. Rep. 15, 341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kato H., Nakajima S., Saito Y., Takahashi S., Katoh R., Kitamura M. (2012) mTORC1 serves ER stress-triggered apoptosis via selective activation of the IRE1-JNK pathway. Cell Death Differ. 19, 310–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ozcan U., Ozcan L., Yilmaz E., Düvel K., Sahin M., Manning B. D., Hotamisligil G. S. (2008) Loss of the tuberous sclerosis complex tumor suppressors triggers the unfolded protein response to regulate insulin signaling and apoptosis. Mol. Cell 29, 541–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bastie C. C., Zong H., Xu J., Busa B., Judex S., Kurland I. J., Pessin J. E. (2007) Integrative metabolic regulation of peripheral tissue fatty acid oxidation by the SRC kinase family member Fyn. Cell Metab. 5, 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamada E., Bastie C. C., Koga H., Wang Y., Cuervo A. M., Pessin J. E. (2012) Mouse skeletal muscle fiber-type-specific macroautophagy and muscle wasting are regulated by a Fyn/STAT3/Vps34 signaling pathway. Cell Rep. 1, 557–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cao Y., Wang Y., Abi Saab W. F., Yang F., Pessin J. E., Backer J. M. (2014) NRBF2 regulates macroautophagy as a component of Vps34 Complex I. Biochem. J. 461, 315–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hayashi A., Kasahara T., Iwamoto K., Ishiwata M., Kametani M., Kakiuchi C., Furuichi T., Kato T. (2007) The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-induced XBP1 splicing during brain development. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34525–34534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maiuolo J., Bulotta S., Verderio C., Benfante R., Borgese N. (2011) Selective activation of the transcription factor ATF6 mediates endoplasmic reticulum proliferation triggered by a membrane protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7832–7837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dufner A., Thomas G. (1999) Ribosomal S6 kinase signaling and the control of translation. Exp. Cell Res. 253, 100–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fadden P., Haystead T. A., Lawrence J. C., Jr. (1997) Identification of phosphorylation sites in the translational regulator, PHAS-I, that are controlled by insulin and rapamycin in rat adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 10240–10247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jiang Y. P., Ballou L. M., Lin R. Z. (2001) Rapamycin-insensitive regulation of 4e-BP1 in regenerating rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 10943–10951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Samali A., Fitzgerald U., Deegan S., Gupta S. (2010) Methods for monitoring endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 830307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Deldicque L. (2013) Endoplasmic reticulum stress in human skeletal muscle: any contribution to sarcopenia? Front. Physiol. 4, 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schiaffino S., Reggiani C. (2011) Fiber types in mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol. Rev. 91, 1447–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shin J., Tajrishi M. M., Ogura Y., Kumar A. (2013) Wasting mechanisms in muscular dystrophy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45, 2266–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thomas D. R. (2007) Loss of skeletal muscle mass in aging: examining the relationship of starvation, sarcopenia and cachexia. Clin. Nutr. 26, 389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Russ D. W., Wills A. M., Boyd I. M., Krause J. (2014) Weakness, SR function and stress in gastrocnemius muscles of aged male rats. Exp. Gerontol. 50, 40–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bonetto A., Aydogdu T., Kunzevitzky N., Guttridge D. C., Khuri S., Koniaris L. G., Zimmers T. A. (2011) STAT3 activation in skeletal muscle links muscle wasting and the acute phase response in cancer cachexia. PLoS One 6, e22538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Egerman M. A., Glass D. J. (2014) Signaling pathways controlling skeletal muscle mass. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 49, 59–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang Y., Pessin J. E. (2013) Mechanisms for fiber-type specificity of skeletal muscle atrophy. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 16, 243–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Russell R. C., Yuan H. X., Guan K. L. (2014) Autophagy regulation by nutrient signaling. Cell Res. 24, 42–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ozcan U., Cao Q., Yilmaz E., Lee A. H., Iwakoshi N. N., Ozdelen E., Tuncman G., Görgün C., Glimcher L. H., Hotamisligil G. S. (2004) Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science 306, 457–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Woehlbier U., Hetz C. (2011) Modulating stress responses by the UPRosome: a matter of life and death. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36, 329–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fung T. S., Liao Y., Liu D. X. (2014) The endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor IRE1α protects cells from apoptosis induced by the coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. J. Virol. 88, 12752–12764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Neisch A. L., Speck O., Stronach B., Fehon R. G. (2010) Rho1 regulates apoptosis via activation of the JNK signaling pathway at the plasma membrane. J. Cell. Biol. 189, 311–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vallerie S. N., Hotamisligil G. S. (2010) The role of JNK proteins in metabolism. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 60rv5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Verma G., Datta M. (2012) The critical role of JNK in the ER-mitochondrial crosstalk during apoptotic cell death. J. Cell. Physiol. 227, 1791–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Salminen A., Kaarniranta K. (2010) ER stress and hormetic regulation of the aging process. Ageing Res. Rev. 9, 211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]