Abstract

Mood fluctuations are problematic in bipolar disorder. Current approaches to frequent monitoring of mood in bipolar disorder are paper diaries and electronic handheld devices. These approaches are limited in several ways, notably in the reliability of the data being collected which is often retrospectively reported. The experience sampling method offers a research paradigm which could be modified for use in clinical settings, to real time frequent mood monitoring. Mobile phone technology has also recently been developed to monitor weekly mood in a bipolar sample, demonstrating successful compliance rates. We propose the use of mobile phone technology as a novel method for frequently monitoring mood in bipolar disorder.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, mood monitoring, experience sampling, mobile phones, SMS

Mood fluctuations are problematic in bipolar disorder

Emotional volatility is a characteristic feature of bipolar disorder, but our understanding of problematic mood fluctuations remains limited. Long term chronic mood instability defines a poor clinical outcome for some patients (Akiskal, 1994; Akiskal, et al., 1995; Holmes, Geddes, Colom, & Goodwin, 2008). In the short term, mood fluctuations can occur frequently when individuals with or without mood disorder react to stressors in their daily lives (Goodwin & Holmes, 2009; Havermans, Nicolson, Berkhof, & Devries, 2010; Havermans, Nicolson, & deVries, 2007; Myin-Germeys, et al., 2003; Ruggero & Johnson, 2006). Mood reactions to stressful life events can be particularly tumultuous for patients given their potential to trigger manic or depressive episodes (Alloy, et al., 2005; Johnson, et al., 2008; Malkoff-Schwartz, et al., 1998).

Thus, mood volatility has the potential to create a persistent state of mood instability regardless of whether a patient is euthymic or not (Benazzi, 2004; M’Bailara, et al., 2009). For a case study concerning one variety of fluctuation see Lam and Mansell (2008). We need to improve our understanding of such fluctuations. We argue in this paper that improving the methods by which we collect information on frequent mood fluctuations is key to encourage self-monitoring in patients and better recognise prodromal symptoms in the prevention of relapse.

Current approaches to frequent mood monitoring

Mood monitoring in the clinic during psychosocial treatment of bipolar disorder has typically utilised paper mood charts on a weekly basis (Miklowitz, Goodwin, Bauer, & Geddes, 2008), see for example Colom and Vieta (2006). Completion of these mood charts in bipolar disorder has predominantly been retrospective. This may mean recalling mood states after several days or, in the case of Life Charts, after weeks or even months. Such information is liable to recall biases as well as being time consuming for clinicians to review such information (Bopp, Miklowitz, Goodwin, Rendell, & Geddes, 2010). Whilst such mood charts continue to be used in bipolar treatment, they could be improved and their limitations render their clinical and research value questionable.

Methods of symptom monitoring in the laboratory may provide clinicians with a more refined method of frequently monitoring mood and provide a constructive adjunct to monitoring outcomes in both psychological and pharmacological treatments. Research paradigms such as ecological momentary assessment (EMA; Stone & Shiffman, 1994) and the experience sampling method (ESM; Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1983) involve repeatedly assessing variables of interest over time in the instantaneous context of participants’ daily lives. Data are collected prospectively, where participants self-report on mood, stress, thoughts, activities and so forth multiple times a day for up to six days in paper diaries (Havermans, et al., 2010; Havermans et al., 2007; Myin-Germeys, et al., 2003). Not only does this methodology allow for charting mood variation within a day and across six days, but it also allows for quantifying ‘reactivity.’ Specifically, the repeated assessment of variables allows researchers to examine how one variable may change in the relation to another. In mood disorders, the primary interest has been the change in mood in response to daily stressors (Wenze & Miller, 2010).

Examples of frequent mood monitoring in bipolar disorder

In bipolar disorder, Havermans, et al. (2007) used ESM to compare 38 patients with remitted BD to 38 healthy controls. Participants were asked to report (10 times a day for 6 days) whether they had experienced a positive or negative event and how pleasant, stressful and important the event was. A sub-sample of patients with a higher number of past depressive episodes perceived negative events to be more stressful. Myin-Germeys et al. (2003) used ESM to investigate mood reactivity in patients with major depressive disorder, non-affective psychosis, and bipolar patients in remission. Patients with bipolar disorder demonstrated reactivity to stress where as stress increased, positive affect decreased. Putting mood fluctuations in context (of stress) would be potentially very valuable in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Presently, to our knowledge, these paradigms have not yet been extended for clinical use in symptom monitoring in any mood disorder (Wenze & Miller, 2010).

As previously stated, refining methods of frequent mood monitoring in bipolar disorder is paramount if relapse signatures are to be identified during and between treatment. In fact mood monitoring may be useful for a variety of reasons, focussing on ‘wellness’ in addition to “pathology”. For example, it could also be useful to help clients to identify what their normal mood fluctuations are like, so that they are able to be aware of and accept a ‘bandwidth’ of changes in mood, as well as recognising when their mood goes outside this range. The use of paper diaries in EMA and ESM has been criticised, because it assumes the participants’ compliance with the method, when in fact paper diaries can always be completed retrospectively (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003). Participants have also been found to complete diary entries ahead of the allotted monitoring-time (Stone, Shiffman, Schwartz, Broderick, & Hufford, 2003). In a sample of patients who display low compliance to prescribed medication (Lingam & Scott, 2002), the long training sessions involved with paper and pencil mood charting as well as the increased likelihood of misplacing the charts suggest that paper mood monitoring would be a potential hindrance to clinical work in a bipolar sample.

For these reasons, the use of paper diaries has sometimes been superseded by handheld electronic data collection devices such as personal digital assistants (PDA; Barrett & Barrett, 2001; Shiffman, 2000). Crucially, the reliability of the data is increased because the time at which the participant responds to the monitoring is accurately recorded. But only a few research studies have utilised electronic data collection in bipolar samples (Bauer, et al., 2005; Scharer, et al., 2002). A significant drawback of such electronic handheld devices is the cost: not only in the tool itself but in the development of the necessary software. Consequently any electronic malfunction would also prove costly (Bolger, et al., 2003). In less developed societies or at a time when funding for both the health care system and scientific research faces cuts, such methods do not seem widely translatable to the clinic. Lengthy training sessions are also required for electronic devices, which may prove fatal to successful monitoring if participants are not computer literate. Whilst electronic handheld devices resolve the primary problems around frequent data collection using paper diaries, they remain infeasible to wider application in clinical settings.

A 21st century approach to mood monitoring: Short Message Service (SMS)

Research has provided a way in which mood monitoring can be improved. Using methods such as EMA and ESM, researchers are able to observe detailed variability of mood over time and the reactivity of an individual to a particular context. The premise of EMA and ESM paradigms are to collect multiple assessments in the context of normal daily life. Frequently completing a paper diary or a PDA, i.e. interjecting a foreign data collection instrument into participants’ daily lives, may have a major negative impact on the validity of the data. Clinically, the frequent use of socially unusual instruments could render an element of stigmatisation.

Consequently, we advocate utilising participants’ own mobile phones as a novel method for frequently monitoring mood in bipolar disorder. This SMS system was recently developed at Oxford University, where the need for an inexpensive and uncomplicated method of frequently collecting mood data in bipolar patients was recognised (Bopp, et al., 2010; Geddes, 2008). Participants are signalled by their phones to respond to a question, to which they simply have to text back their response by short message service (SMS). Similar to PDAs, the reliability of data is increased by the ability to record the time at which the participant responds. Mobile phones are very widely used and understood. Little social stigma is attached to the frequent use of mobile phones, thus this method of data collection may have good acceptability. This approach has already been utilised in collecting weekly mood stability data for an average of 36 weeks in a bipolar sample, where, given the 75% compliance rate of weekly texts, it was shown to be a feasible method for the regular assessment of mood over time (Bopp, et al., 2010; see also Bonsall, Wallace-Hadrill, Geddes, Goodwin, & Holmes, 2011).

From the lab to the clinic: SMS monitoring in practice

Presently, the use of mobile phone technology has rarely (and only recently) been employed in conjunction with EMA and ESM paradigms. Studies are beginning to appear which use mobile phone technology with ESM and EMA frameworks. For example Reid et al (2009) assert they were the first to utilise mobile phones with ESM. They monitored current activity, mood, responses to negative mood, stresses, alcohol and cannabis use in a sample of 18 adolescents showing a good level of use of the system, though detailed conclusions are precluded by the small sample size. The use of mobile phone technology under an ESM or EMA framework for bipolar disorder is limited. Depp et al (2010) used mobile phones with an experience sampling framework to facilitate case management for clients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Other mobile phone programs for mood disorder have recently been developed and are currently being evaluated in clinical trials, for which we eagerly await the results. For a commercially available system for monitoring depression and bipolar disorder, see the “optimism” application which is available on the internet and as an iPhone application (“optimism apps,” 2007).This allows users to track their mood and behaviour, observe charts of their data, identify triggers and plan wellness strategies. Future results from this promise exciting developments.

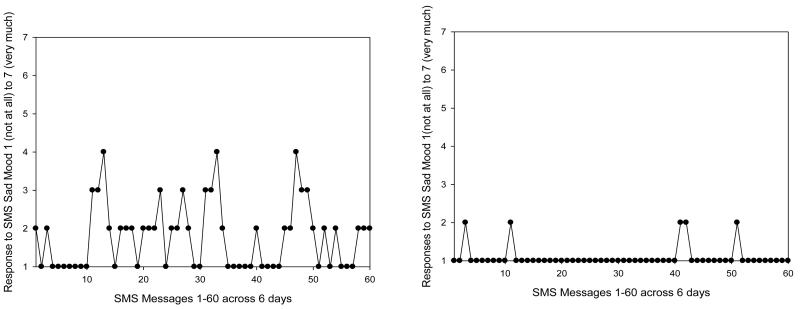

In a clinical environment the intense frequency of the data collection may not be suitable for monitoring bipolar mood over a long period of time. We have piloted the development of an SMS interface that would be more suitable for frequent mood monitoring in a bipolar sample, which allows for charting mood (and any other variable of interest, such as sleep) on a more frequent basis than just weekly. A recent paper from our clinic by Bopp et al. (2010) provides an example of the SMS interface in action for weekly data using our system, see also Holmes et al (2011). Presently, a week-long more intensive ESM study is in progress. Individuals are asked to rate their mood in reference to an adjective, for example ‘depressed’. They rate the mood word on a 1-7 Likert scale (anchored from not at all – very much) as to what extent they are experiencing the mood at the moment in time that they text back. Participants are prompted to respond 10 times a day for 6 days” For an example of depressed mood ratings over 6 days, please see Figure 1, which illustrates one participant with high mood variability and one with a more stable mood profile. Of qualitative interest, participants in the study have spontaneously reported benefits from becoming more aware of their daily mood. Compliance to the SMS interface to date is good with no individuals being unable to complete any responses at all, and 91/97 participants able to complete at least 20% of the total responses (the required amount for inclusion in ESM analysis, (Delespaul, 1992).

Figure 1.

Two mood output charts of depressed mood when sampled 10 times daily for 6 days for one participant with high mood variability (left hand side) and one participant showing a clearly stable mood profile (right hand side).

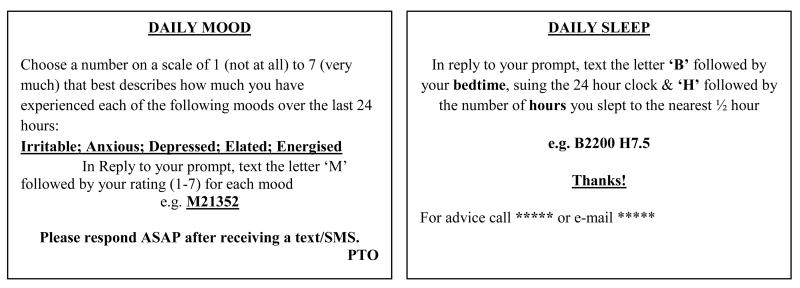

It could be used in tandem with other convergent objective measures e.g. actigraphy for sleep (Jones, Hare, & Evershed, 2005). We advocate this approach to be both usable for the participant and feasible for the clinician/researcher. For example, as individuals are familiar with their own phones, only a short 15 minute orientation to the instructions is required. In addition to this, participants are provided with credit card sized instructions to carry with them, which are designed to assist them in responding to the SMS prompts (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Credit card sized instructions used to assist users in responding to SMS prompts for daily mood and daily sleep.

Users of this approach text their response to each message they receive, and their reply is automatically captured by central computer system. The investigator can easily generate and interpret a mood chart for visual inspection by the patient and clinician. Mood data is collected ‘there and then’ so that the mood chart is an accurate as possible reflection of the user’s mood during the week. There is no risk of mood charts being lost. Such a chart would prove a useful adjunct to therapy and is akin to a one week cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) mood chart. Whilst the emphasis of this paper regards mood fluctuations in response to stress, we recognise that there are further bipolar-related variables which could provide richer information in therapy. Mobile phone technology is flexible and could be used to sample other variables of relevance to bipolar disorder in addition to mood such as daily activities (Myin-Germeys, et al., 2003), goals and planning (Johnson, 2005), memories, (Gruber, Harvey, & Johnson, 2009) and intrusive future images (Deeprose, Malik, & Holmes, 2011). Further adaptations of the SMS system could include monitoring a bespoke variety of beliefs, behaviours, thoughts and imagery (Malik, Goodwin, Holmes, 2011), which tracked over time would provide richer CBT-relevant information.

There is an exciting emergence of new technologies and applications for mood monitoring. For example, the “mappiness” application on the iPhone (“mappiness,” 2010) allows someone to monitor how their feelings of happiness change according to their environment. One can imagine how technologies such as this could be refined to help people with mood swings e.g. in identifying environmental triggers. We acknowledge that reactions to stressors, whilst an important starting point, may not be the only cause of mood instability. Long-term instabilities in self-regulatory systems could also be caused by multiple systems with conflicting standards (Mansell, Morrison, Reid, Lowens, & Tai, 2007) whereby no stable mood is reached and the individual oscillates between two mood states. The flexibility of monitoring via mobile phones would allow for clients to provide feedback about their own goals and emotion regulation attempts. Future developments could expand SMS technology, and exploit the opportunity not only for numerical responses but for more qualitative data via written verbal text messages, to test this.

Another useful future development would be to collect situational information at the time of the ESM/EMA mood ratings, in a bid to enhance the utility of the ‘just in time and just in place’ ratings and in better understanding mood fluctuations and relapse signatures. For example, knowledge about situation information from a series of text messages could be reviewed and highlight what situational triggers might lead to a change in mood. Presently we are using the SMS interface to collect information about participants’ stress-context (in conjunction with their mood) by asking them to briefly describe the most important event that has occurred to them since the previous message that was sent to them that day. Participants then rate this event for how pleasant they found it on a Likert scale of 1 (not at all pleasant) to 7 (very pleasant). An example of the former type of event might be “being diagnosed with diabetes” and for a very pleasant event “a meal in a lovely restaurant in Oxford”.

Utilising mobile phone technology may prove to be a practical method of frequently monitoring mood (and other variables) in bipolar disorder. Mobile phone monitoring improves on the limitations of paper diaries and PDAs that are currently in use, by increasing the reliability of the data being collected and potentially increasing acceptability and frequency of responding in participants. However, there are challenges of using this type of mobile phone monitoring, such as ensuring privacy and security, as personal data could be attributed to a personal contact number. Another issue is that of managing risk if a client, for example, has generated high scores. Clearly, this is a topic which requires clinical sensitivity and ethical decisions at a local level. For an overview see Proudfoot and Nicholas (2010) and Shapiro and Bauer (2010). This novel approach is intended to aid clinicians and researchers in better recognising prodromal symptoms as well. It is hoped that this system will allow patients to have control over monitoring their own mood variation. Moreover, it forms part of a more computerised vision of improving the care and treatment of people with mental health difficulties (Cavanagh, Van Beck, Muir, & Blackwood, 2002; Marks, Cavanagh, & Gega, 2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the OXTEXT team in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford and in particular Professor John Geddes.

This research was supported by a Medical Research Council Studentship awarded to Aiysha Malik and a Wellcome Trust Clinical Fellowship to Emily Holmes (WT088217). The development of the SMS mood monitoring reviewed in this paper was supported by the National Institute for Health Research and Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

References

- Akiskal HS. The temperamental borders of affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica. Scandinavica. Supplementum. 1994;89(379):32–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05815.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, Keller M, Goodwin F. Switching from ‘unipolar’ to bipolar II. An 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental predictors in 559 patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(2):114–123. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950140032004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950140032004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Urosevic S, Walshaw PD, Nusslock R, Neeren AM. The psychosocial context of bipolar disorder: Environmental, cognitive, and developmental risk factors. [Review] Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(8):1043–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Barrett DJ. An introduction to computerized experience sampling in psychology. Social Science Computer Review. 2001;19(2):175–185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/089443930101900204. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, Altshuler L, Evans DR, Beresford T, Williford WO, Hauger R. Prevalence and distinct correlates of anxiety, substance, and combined comorbidity in a multi-site public sector sample with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;85(3):301–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benazzi F. Inter-episode mood lability in mood disorders: residual symptom or natural course of illness? Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2004;58(5):480–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01289.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsall MB, Wallace-Hadrill SMA, Geddes JR, Goodwin GM, Holmes EA. Nonlinear time-series approaches in characterizing mood stability and mood instability in bipolar disorder. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2011 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.1246. 10.1098/rspb.2011.1246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp MJ, Miklowitz DJ, Goodwin GM, Rendell JM, Geddes JR. The longitudinal course of bipolar disorder as revealed through weekly text messaging: a feasibility study. Bipolar Disorders. 2010;12:327–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00807.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JTO, Van Beck M, Muir M, Blackwood DHR. Case-control study of neurocognitive function in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder: An association with mania. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:320–326. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.4.320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F, Vieta E. Psychoeducation manual for bipolar disorder. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511543685. [Google Scholar]

- Deeprose C, Malik A, Holmes EA. Measuring intrusive prospective imagery using the Impact of Future Events Scale (IFES): Psychometric properties and relation to risk for bipolar disorder. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2011;4(2):187–196. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2011.4.2.187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2011.4.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delespaul PA. Technical note: Devices and time-sampling procedures. In: de Vries MW, editor. The experience of psychopathology: Investigating mental disorders in their natural settings. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1992. pp. 363–376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511663246.033. [Google Scholar]

- Depp CA, Mausbach B, Granholm E, Cardenas V, Ben-Zeev D, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Mobile Interventions for Severe Mental Illness Design and Preliminary Data From Three Approaches. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010;198(10):715–721. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181f49ea3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181f49ea3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes J, NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement Let your thumbs do the talking: Case study: Oxford University Department of Psychiatry. 2008 Retrieved 26 September, 2008, from http://www.institute.nhs.uk/images/documents/NHS%20Live/NHS%20LIVE%20Case%20Studies%20Let%20your%20thumbs%20do%20the%20talking.pdf.

- Goodwin GM, Holmes EA. Bipolar anxiety. Revista de Psiquiatria Y Salud Mental. 2009;02(02):95–98. doi: 10.1016/S1888-9891(09)72251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Harvey AG, Johnson SL. Reflective and ruminative processing of positive emotional material memories in bipolar disorder and healthy controls. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havermans R, Nicolson N, Berkhof J, Devries MW. Mood reactivity to daily events in patients with remitted bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2010;179(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havermans R, Nicolson NA, de Vries MW. Daily hassles, uplifts, and time use in individuals with bipolar disorder in remission. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(9):745–751. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318142cbf0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e318142cbf0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, Deeprose C, Fairburn CG, Wallace-Hadrill SMA, Bonsall MB, Geddes JR, Goodwin GM. Mood stability versus mood instability in bipolar disorder: A possible role for emotional mental imagery. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49(10):707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, Geddes JR, Colom F, Goodwin GM. Mental imagery as an emotional amplifier: Application to bipolar disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(12):1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.09.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL. Mania and dysregulation in goal pursuit: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(2):241–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.11.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Cueller AK, Ruggero C, Winett-Perlman C, Goodnick P, White R. Life Events as Predictors of Mania and Depression in Bipolar I Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:268–277. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SH, Hare DJ, Evershed K. Actigraphic assessment of circadian activity and sleep patterns in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorder. 2005;7(2):176–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00187.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam DH, Mansell W. Mood dependent cognitive change in a man with bipolar disorder whose cycles every 24 hours. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2008;15:255–262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2007.09.002. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Csikszentmihalyi M, editors. The experience sampling method. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. [Review] Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;105(3):164–172. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r084.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- M’Bailara K, Chevrier F, Dutertre T, Demotes-Mainard J, Swendsen J, Henry C. Emotional reactivity in euthymic bipolar patients. Encephale-Revue De Psychiatrie Clinique Biologique Et Therapeutique. 2009;35(5):484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Goodwin GM, Holmes EA. The broad bipolar phenotype in young people confers vulnerability to flashback memories after an experimental trauma. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Malkoff-Schwartz S, Frank E, Anderson B, Sherrill JT, Siegal L, Patterson D, Kupfer DJ. Stressful life events and social rhythm disruption in the onset of manic and depressive bipolar episode. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:702–707. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.702. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W, Morrison AP, Reid G, Lowens I, Tai S. The interpretations of, and responses to, changes in internal states: An intergrative cognitive model of mood swings. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2007;35(5):515–539. [Google Scholar]

- Mappiness . London School of Economics; 2010. Version http://www.mappiness.org.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- Marks IM, Cavanagh K, Gega L. Computer-aided Psychotherapy: a revolution or a bubble about to burst? British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;191:471–473. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.041152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.041152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Goodwin GM, Bauer MS, Geddes JR. Common and specific elements of psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder: a survey of clinicians participating in randomized trials. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2008;14:77–85. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000314314.94791.c9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000314314.94791.c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Peeters F, Havermans R, Nicolson NA, deVries MW, Delespaul P, van Os J. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis and affective disorder: an experience sampling study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;107(2):124–131. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02025.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Optimism Apps . Optimism Apps Pty Ltd; 2007. Version http://www.findingoptimism.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot J, Nicholas J. Monitoring and evaluation in low intensity CBT interventions. In: Bennett-Levy J, Richards D, Farrand P, Christensen H, Griffiths K, Kavanagh D, Klein B, Lau M, Proudfoot J, Ritterband L, White J, Williams C, editors. Oxford Guide to Low Intensity CBT Interventions. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Reid SC, Kauer SD, Dudgeon P, Sanci LA, Shrier LA, Patton GC. A mobile phone program to track young people’s experiences of mood, stress and coping. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44(6):501–507. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0455-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggero CJ, Johnson SL. Reactivity to a Laboratory Stressor Among Individuals With Bipolar I Disorder in Full or Partial Remission. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:539–544. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.539. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharer LO, Hartweg V, Hoern M, Graesslin Y, Strobl N, Frey S, Walden J. Electronic diary for bipolar patients. Neuropsychobiology. 2002;46(1):10–12. doi: 10.1159/000068021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000068021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JR, Bauer S. Use of short message service (SMS) based interventions to enhance low intensity CBT. In: Bennett-Levy J, Richards D, Farrand P, Christensen H, Griffiths K, Kavanagh D, Klein B, Lau M, Proudfoot J, Ritterband L, White J, Williams C, editors. Oxford Guide to Low Intensity CBT Interventions. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Real-time self-report of momentary states in the natural environment: computerized ecological momentary assessment. In: Stone AA, Turkkan JS, Bachrach CA, Jobe JB, Kurtzman HS, Cain VS, editors. The Science of Self-reports: Implications for Research and Practice. Erlbaum; Mahwah, N.J.: 2000. pp. 277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Hufford MR. Patient compliance with paper and electronic diaries. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2003;24:182–199. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00320-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0197-2456(02)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenze SJ, Miller IW. Use of ecological momentary assessment in mood disorders research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]