Abstract

Background

Cronobacter sakazakii and C. malonaticus can cause serious diseases especially in infants where they are associated with rare but fatal neonatal infections such as meningitis and necrotising enterocolitis.

Methods

This study used 104 whole genome sequenced strains, covering all seven species in the genus, to analyse capsule associated clusters of genes involved in the biosynthesis of the O-antigen, colanic acid, bacterial cellulose, enterobacterial common antigen (ECA), and a previously uncharacterised K-antigen.

Results

Phylogeny of the gnd and galF genes flanking the O-antigen region enabled the defining of 38 subgroups which are potential serotypes. Two variants of the colanic acid synthesis gene cluster (CA1 and CA2) were found which differed with the absence of galE in CA2. Cellulose (bcs genes) were present in all species, but were absent in C. sakazakii sequence type (ST) 13 and clonal complex (CC) 100 strains. The ECA locus was found in all strains. The K-antigen capsular polysaccharide Region 1 (kpsEDCS) and Region 3 (kpsMT) genes were found in all Cronobacter strains. The highly variable Region 2 genes were assigned to 2 homology groups (K1 and K2). C. sakazakii and C. malonaticus isolates with capsular type [K2:CA2:Cell+] were associated with neonatal meningitis and necrotizing enterocolitis. Other capsular types were less associated with clinical infections.

Conclusion

This study proposes a new capsular typing scheme which identifies a possible important virulence trait associated with severe neonatal infections. The various capsular polysaccharide structures warrant further investigation as they could be relevant to macrophage survival, desiccation resistance, environmental survival, and biofilm formation in the hospital environment, including neonatal enteral feeding tubes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1960-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cronobacter, Capsule formation, Genomic analysis

Background

Capsular polysaccharides (CPS) are major bacterial virulence factors and environmental fitness traits. In Gram-negative bacteria, the CPS forms a surface layer of water-saturated, high molecular weight polysaccharides which enable the organism to evade host response mechanisms such as phagocytosis as well as facilitate biofilm formation and desiccation survival [1]. CPS vary considerably between organisms, and even between strains of the same species. Capsular diversity has been the basis for a number of bacterial differentiation methods including serotyping of Salmonella serovars and the K-antigen classification scheme of E. coli [2]. The use of whole genome data can now serve to expand and clarify these schemes. Such analysis can also reveal the extent of horizontal gene transfer leading to the lack of congruence between serotype and phylogeny due to the transference of loci (ie. rfb locus) between strains.

In Gram-negative bacteria the O-antigen and K-antigen are composed of long polysaccharide units which are covalently linked to lipid A in the outer membrane. The O-antigen is a major surface antigen. Genes involved in O-antigen synthesis are in the rfb locus between the flanking genes gnd and galF [3]. The locus varies in size for each serotype according to the sugar composition and complexity of structure, ie. phosphorylation. These genes encode for enzymes involved in the synthesis of sugars forming the O-antigen subunit, genes that encode glycosyltransferases (required for the assembly of sugar substituents in the O-antigen subunit) and genes such as wzx and wzy. The latter encode for the transporter and polymerase proteins necessary for processing and assembly of the O-antigen from the subunits.

The K-capsule of E. coli is composed of the highly conserved Regions 1 (kpsFEDUCS) and 3 (kpsMT), and a variable Region 2 [1, 2]. Regions 1 and 3 encode for enzymes and transport proteins responsible for initiation of chain elongation and translocation to the cell surface. Region 2 genes encode the glycosyltransferases and other enzymes responsible for biosynthesis of the K-antigen-specific CPS such as neu genes for the polysialic acid capsule in the neonatal meningitic E. coli K1 pathovar.

Many Gram-negative bacteria also secrete a variety of high molecular weight glycopolymers, known as exopolysaccharides (EPS), which contribute to biofilm formation [4, 5]. The enterobacterial common antigen (ECA) is a linear heteropolysaccharide which is bound to the outer membrane. It is composed of → 3)-α-DFucp4NAc-(1 → 4)-β-D-ManpNAcA-(1 → 4)-α-DGlcpNAc-(1 → (2–4), modified with O-acetyl groups as a repeating trisaccharide unit. Three variations in ECA have previously been described; ECAPG linked to phosphatidylglycerol, ECALPS covalently bound to the lipid A core structure, and ECACYC which is a periplasmic water-soluble cyclic form [6]. Most of the genes involved in the assembly of ECA are located in the wec gene cluster [7, 8]. Another exopolysaccharide, called colanic acid (CA) is loosely bound to the cell. CA may also be secreted into the environment where it contributes to bacterial biofilm structure [4]. Enterobacteriaceae also synthesize an exopolysaccharide known as bacterial cellulose, or poly-β-1,4-glucan, which forms part of the bacterial extracellular matrix [9]. Regulatory expression and secretion of these EPS can be influenced by various factors, for example the thermoregulated synthesis of polysialic acid and colanic acid in E. coli [10].

The bacterial pathogen Cronobacter has become the focus of much attention especially due to its association with neonatal meningitis [11]. A number of potential virulence traits have been proposed, most recently the production of outer membrane vesicles [12–14]. Most strains of Cronobacter are able to survive and even replicate inside macrophages for up to 2 days [15, 16]. The genus is composed of seven species, for which an open access international multilocus sequence typing database has been established; http://pubmlst.org/cronobacter/ [17–19]. This database has enabled the recognition of certain Cronobacter clonal lineages as pathovars; C. sakazakii clonal complex (CC) of ST4 are more predominantly associated with neonatal meningitis, C. sakazakii ST12 with neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis, and C. malonaticus ST7 with adult infections [13, 17–20]. However genome comparison studies have not revealed virulence traits unique to these Cronobacter pathovars [14, 20, 21].

In Cronobacter the O-antigen gene cluster contains between 6 and 19 genes, and varies between 6–20 kb in length. It is flanked by gnd and galF (encoding 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase and UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase subunit, respectively) [21, 22]. The variation in the rfb cluster has been used to develop random fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) profiling across the region and PCR assays targeting the presumed conserved serotype-specific genes wzx and wzy [23, 24]. Until recently there were only 18 defined serotypes across the whole genus, with only 7 in C. sakazakii and 2 in C. malonaticus, respectively [22–27]. There are however contradictions in the literature such as C. sakazakii O5 and O6 being proposed as mis-identified strains of C. malonaticus [26, 27]. In addition, RFLP and PCR-probes are unable to detect all sequence based variations which may be outside their target site. Consequently, Blažková et al. [27], based on their more detailed analysis, proposed the O-antigen scheme should be expanded, with additional recognition of 7 new and 2 re-assigned serotypes. Cronobacter serotyping has been supported in part by chemical analysis of the O-antigen polysaccharide (O-PS) from many strains [28–32]. However three structures have been determined for C. sakazakii O2 strains [28–30]. This observation supports the proposal that the current RFLP and PCR-probes are unable to distinguish some variants in the O-antigen.

An additional complication with current O-antigen assignment is that the targeted genes do not follow whole genome phylogeny of the genus [14]. There is evidence that horizontal gene transfer has occurred in the rfb region. For example, the same O-antigen serotype sequences in the wzx and wzy genes are used as target sites for different Cronobacter species such as C. malonaticus O1 and C. turicensis O1 [24]. Also some homologies are found in different species and genera, as occurs with C. sakazakii O3 and C. muytjensii O1 with E. coli O29 and C. sakazakii O4 with E. coli O103 [24, 25, 32]. Therefore currently O-antigen serotyping can only be determined after the Cronobacter isolates have been first accurately speciated. However this too has been problematic due to the reliance on phenotyping as well as rpoB and cgcA PCR probes which have even mis-identified infant infections as C. sakazakii instead of the correct identification of E. hormaechei [33, 34].

Given the smaller number of serotypes than MLST defined sequence types (24 compared to >350) it is not unexpected that several sequence types occur in each serotype. Based on >1000 entries in the Cronobacter PubMLST database, C. sakazakii serotype O2 contains 28 defined sequence types [17]. The relatively small number of serotypes again indicates the possibility that the current RFLP and PCR-probe methods may not be robust enough to distinguish many DNA sequence variations. Serotype polymorphisms have been determined in Shiga-toxin producing E. coli following the sequencing of a 643 bp region of the gnd loci which is one of the O-antigen flanking genes [3]. Since >100 Cronobacter spp. genomes are available in the public domain, a similar sequence (allele) based serotyping approach using either or both of the O-antigen flanking genes can be considered which may overcome the current laborious approach requiring 15 primer pairs.

Cronobacter does produce EPS and forms biofilms on inert surfaces that are more resistant to cleaning and disinfectant agents [35–38]. Reported sources of Cronobacter in the hospital environment include infant formula preparation equipment, feeding bottles, and neonatal enteral feeding tubes [11, 34–37, 39]. The latter could act as loci for neonatal infection [35, 36].

In Cronobacter optimal EPS production is under nitrogen-limited growth conditions and is influenced by milk components [40, 41]. Consequently the organism has a notable extensive mucoid appearance on milk agar plates which causes the growth to drip on to the inverted lid [42]. The unique biophysical properties of this capsular material has led to patents being filed for its exploitation as a thickening agent in foods to replace xanthan gum [43]. Such capsular material production could also be important in desiccation persistence by the bacterium in the environment, in powdered infant formula (PIF), as well as in serum resistance and macrophage evasion. However, our understanding of the capsule is limited to a few studies on a limited number of strains, some of which were before the taxonomic revision of Enterobacter sakazakii to the genus Cronobacter.

The secreted EPS colanic acid is produced by some strains of C. sakazakii (ATCC 12868 and ATCC 29004) but not the species type strain ATCC 29544T [43, 44]. It is composed of glucuronic acid (29–32), D-glucose (23–30), D-galactose (19-24), D-fucose (13–22) and D-mannose (0–0.8 %). Production of EPS from other named Cronobacter species has not been previously reported. Zogai et al. [9] used Calcofluor dye retention to demonstrate bacterial cellulose production by a commensal Cronobacter spp. strain (species not defined). Later, Lehner et al. [44] used fluorescence microscopy to demonstrate cellulose fibrils formation with a wide range of food and clinical Cronobacter spp. strains which at the time were only identified as Enterobacter sakazakii.

It is plausible that the strong association between C. sakazakii CC4 and neonatal meningitis is due to environmental fitness such as desiccation survival, resulting in their frequent isolation from both PIF and the environment of PIF manufacturing plants in Australia, China, Ireland, Switzerland and Germany [45–48]. Caubilla-Barron & Forsythe [49] reported the prolonged survival of desiccated C. sakazakii and especially capsulated strains in infant formula for over 2 years. This is considerably longer than Salmonella enterica and Citrobacter koseri, which were no longer recoverable after 14 and 8 months respectively.

Given such a wide range of environmental fitness and virulence related traits, it was deemed appropriate to characterise the clusters of capsule production related genes across the Cronobacter genus using the whole genome analysis of >100 strains. These genomes are available for analysis using the Bacterial Isolate Genome Sequence database (BIGSdb)-supported Cronobacter PubMLST open access database [17, 50].

Results

Diversity of Cronobacter O-antigen

The O-antigen polymerase and O-antigen flippase genes, wzy and wzx respectively, within the rfb locus have been the targets for molecular serotyping of Cronobacter species using PCR primers [23, 24]. Therefore they were selected for initial sequence variation and phylogenetic analysis of the O-antigen region. The extracted wzx and wzy sequences from Genbank as well as those from 104 genomes were aligned and phylogenetically analysed. The purpose of this analysis was to show the clustering of the predefined serotypes based on those presumed O-antigen specific sequences. However these genes were not found in all 104 strains of Cronobacter. Wzy was absent from the C. sakazakii O7 reference sequence (JQ674750), and wzx was absent from the genome of C. condimenti 1330T. Furthermore, genomic analysis revealed two novel O-antigen clusters for C. muytjensii which were defined as O3 and O4 (Additional file 1: Table S3). A potentially novel O-antigen region was also revealed in C. dublinensis strain 2030. However it is currently unclear if this matches the newly described C. dublinensis O3 as given by Blažková et al. [27] as the latter has been defined by RFLP restriction pattern and not DNA-sequence. Hence for the purpose of this study the O-antigen of C. dublinensis strain 2030 is referred to as ‘not assigned’ (na).

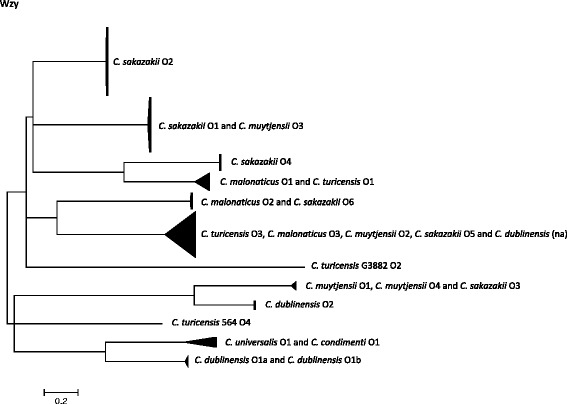

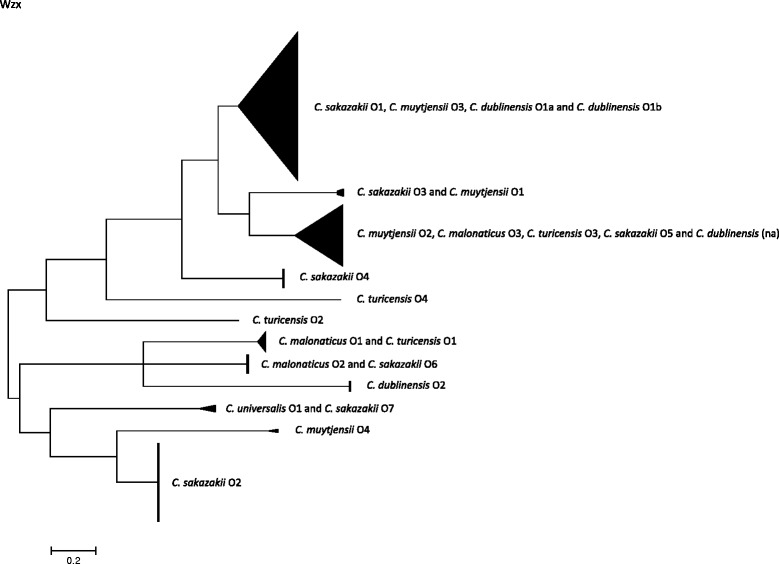

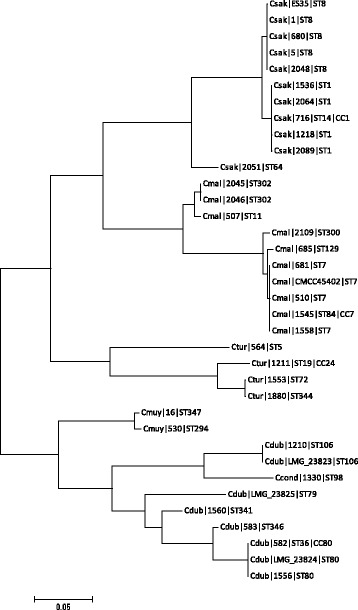

Phylogenetic trees of the whole genes wzy and wzx are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The only corresponding serogroups which formed unique clusters were C. sakazakii serotypes O2, O4 and C. dublinensis O2; Figs. 1 and 2, Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of wzy sequences from across the Cronobacter genus. DNA sequences were aligned in MEGA version 5.2 using the ClustalW algorithm. The phylogenetic trees were generated using the Maximum Likelihood method

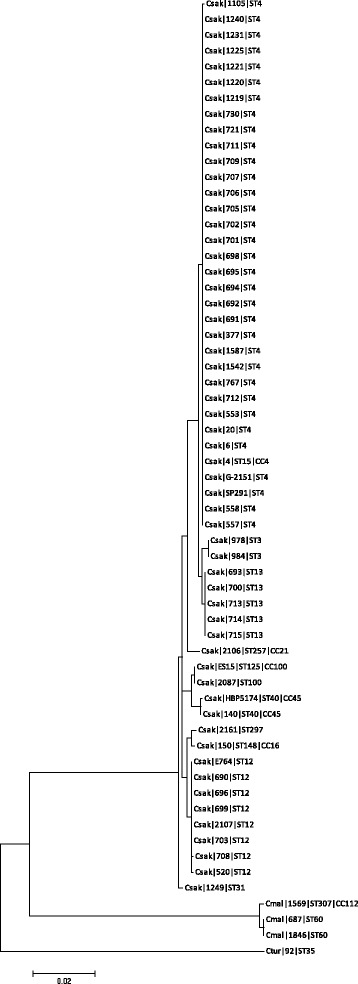

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of wzx sequences from across the Cronobacter genus. DNA sequences were aligned in MEGA version 5.2 using the ClustalW algorithm. The phylogenetic trees were generated using the Maximum Likelihood method

Table 1.

Clustering of Cronobacter O-serotypes according to wzy, wzx, gnd and galF sequence analysis

| Cronobacter species | Serotypea | gnd alleles | galF alleles | wzy cluster group | wzx cluster group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. sakazakii | O1 | 1,3,13,18,21,23 | 1,2,4,17,19,21 | C. muytjensii O3b | C. muytjensii O3, C. dublinensis O1 |

| O2 | 2,13,19,28,29, 37 | 3,18,25,26 | Unique cluster | Unique cluster | |

| O3 | 24 | 22 | C. muytjensii O1 | C. muytjensii O1 | |

| O4 | 14 | 13 | Unique cluster | Unique cluster | |

| O5 | na | na | C. turicensis O3, C. malonaticus O3, C. dublinensis nac, C. muytjensii O2 | C. turicensis O3, C. malonaticus O3, C. dublinensis na, C. muytjensii O2 | |

| O6 | na | na | C. malonaticus O2 | C. malonaticus O2 | |

| O7 | na | na | Absent | C. universalis O1 | |

| C. malonaticus | O1 | 27, 33 | 6, 24 | C. turicensis O1 | C. turicensis O1 |

| O2 | 4, 26, 36 | 5, 23, 32 | C. sakazakii O6 | C. sakazakii O6 | |

| O3 | 5, 38 | 6, 24 | C. sakazakii O5, C. turicensis O3, C. muytjensii O2, C. dublinensis na | C. turicensis O3, C. muytjensii O2, C. dublinensis na | |

| C. turicensis | O1 | 8 | 9, 28 | C. malonaticus O1 | C. malonaticus O1 |

| O2 | na | na | Unique | Unique | |

| O3 | 22, 30, 34 | 20, 27, 30 | C. sakazakii O5, C. malonaticus O3, C. muytjensii O2, C. dublinensis na | C. sakazakii O5, C. malonaticus O3, C. muytjensii O2, C. dublinensis na | |

| O4 | 6 | 7 | Unique | Unique | |

| C. muytjensii | O1 | 17 | 16 | C. sakazakii O3 | C. sakazakii O3 |

| O2 | 16 | 15 | C. sakazakii O5, C. turicensis O3, C. malonaticus O3, C. dublinensis na | C. malonaticus O3, C. turicensis O3, C. dublinensis na | |

| O3 | na | na | C. sakazakii O1 | C. sakazakii O1, C. dublinensis O1 | |

| C. dublinensis | O1 | 12,15 | 12, 14 | Unique cluster | C. sakazakii O1, C. muytjensii O3 |

| O2 | 11, 25, 32 | 11, 29 | Unique cluster | Unique cluster | |

| na | 35 | 31 | C. sakazakii O5, C. malonaticus O3, C. turicensis O3, C. muytjensii O2 | C. malonaticus O3, C. turicensis O3, C. muytjensii O2 | |

| C. universalis | O1 | 7 | 8 | C. condimenti O1 | C. sakazakii O7 |

| C. condimenti | O1 | 9 | 33 | C. universalis O1 | Absent |

The wzy C. sakazakii O2 cluster (n = 45) was composed of 7 sequence types; C. sakazakii ST3, ST4, ST13, ST15 (CC4), ST31, ST64, and ST218 (CC4). C. sakazakii O4 (n = 10) included one strain of C. sakazakii ST4, and all ST12, ST40 and ST45 strains. The wzy gene sequences of C. sakazakii serotypes O1 and O3 were indistinguishable from C. muytjensii O3 and, O1 and O4, respectively. C. sakazakii O5 clustered with C. turicensis O3, C. malonaticus O3, C. dublinensis na and C. muytjensii O2. C. sakazakii O6 was indistinguishable from C. malonaticus O2. C. malonaticus O1 and C. turicensis O1 were indistinguishable. C. sakazakii O7 could not be included in this analysis as the gene wzy is absent.

C. malonaticus O1 wzy cluster included two STs (ST60 & ST307), as well as the C. turicensis O1 (ST19). C. malonaticus O2 contained 8 strains from ST7, ST84, ST129 and ST302. The newly described C. malonaticus O3 cluster contained two C. malonaticus strains (ST11 and ST300) as well as those in C. sakazakii O5, C. turicensis O3, C. muytjensii O2 and C. dublinensis (na).

According to the wzy gene sequence, as given above, C. turicensis serotype O1 clustered with C. malonaticus O1. C. turicensis O3 clustered with C. malonaticus O3, C. muytjensii O2, C. sakazakii O5 and C. dublinensis strain 2030 (serotype not assigned). C. turicensis O2 and O4 were composed of unique strains G3882 and 564, respectively.

As stated above, C. muytjensii O1, O4 and O3 clustered with C. sakazakii O3 and O1 respectively. C. muytjensii O2 clustered with serotypes in four other Cronobacter species; C. sakazakii O5, C. malonaticus O3, C. turicensis O3, and C. dublinensis (na).

C. dublinensis serotypes were split into two distinct clusters; Fig. 1. The C. dublinensis O1 cluster (containing the C. dublinensis subsp. dublinensis type strain and C. dublinensis subsp. lartaridi) was closer to the cluster of C. universalis O1 and C. condimenti O1. Whereas the C. dublinensis O2 cluster (containing C. dublinensis subsp. lausanensis) was close to the cluster of C. sakazakii O3 and C. muytjensii O1 and O4.

The clustering of wzx gene largely reflected that of wzy; Fig. 2, Table 1. The main differences were that C. dublinensis O1 clustered with C. sakazakii O1 and C. muytjensii O3, and that the wzx sequence of C. sakazakii O7 was indistinguishable from C. universalis O1.

Due to the non-phylogenetic congruence of the wzy and wzx sequences, the flanking genes gnd and galF were chosen to further investigate the diversity of the O-antigen region. A total of 38 unique alleles were observed at the gnd locus for the 104 Cronobacter strains. The galF locus generated slightly fewer (33) unique alleles. The additional gnd loci were primarily in C. sakazakii and included single nucleotide variants. The variant genes were assigned profile numbers and are recorded in the Cronobacter PubMLST database and given in Table 1. The allele length (501 bp) was chosen such that the region could easily be targeted by PCR primers in further laboratory analysis.

The detailed phylogenetic trees of galF and gnd are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1 and S2. Nearly the same clustering as for the 38 gnd alleles was also observed with for the 33 galF alleles. Most C. sakazakii strains clustered together, with nearest neighbour C. malonaticus. The six C. turicensis strains all differed in their gnd sequences, and formed a cluster closely related to C. universalis. Similarly C. muytjensii and C. dublinensis clustered together with the C. condimenti. It was notable that the 10 C. sakazakii O4 strains formed a unique outgroup to the rest of the Cronobacter strains. This serotype is mostly composed of C. sakazakii ST12 strains.

The galF allele tree was similar to that of gnd; Additional file 1: Figure S1. C. sakazakii formed distinct clusters. Most were close relatives, whereas one was distant to most members of the genus. C. malonaticus strains formed two clusters, and branched close to the majority of C. sakazakii strains. The three strains of C. muytjensii formed a distinct cluster. These strains were C. muytjensii serotypes O1, O2 and the newly described O3 and O4. The C. turicensis strains all differed in their galF sequences, and formed a cluster closely related to C. universalis. The C. dublinensis strains were clustered into one group according to gnd, but two groups by galF; C. dublinensis subsp. dublinensis and C. dublinensis subsp. lactaridi were distant to C. dublinensis subsp. lausanensis. The latter group clustered with the C. sakazakii O4 cluster, and were distant from the rest of the Cronobacter genus; Additional file 1: Figure S1 and S2.

Cellulose and enterobacterial common antigen diversity

The cellulose gene cluster composed of 9 genes (bcsCZBAQEFG and yhjR) was found in nearly all Cronobacter strains. The exceptions were all (n = 7) C. sakazakii ST13 and CC100 strains and the single strain of C. condimenti 1330T. These were confirmed using Calcofluor agar plates (data not presented).

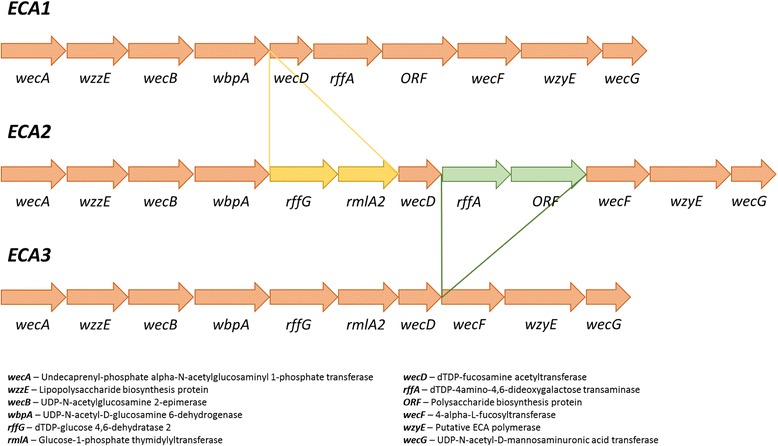

The enterobacterial common antigen (ECA) gene cluster composed of 10–12 genes was found in all Cronobacter strains; Fig. 3, Table 2. There were three variants; ECA1 in all C. sakazakii and C. malonaticus 507, made up of 10 genes, missing rffG and rmlA2, and ECA2 in nearly all other species and strains, made up of 12 genes. Other variations were the absence of rffA and ORF1 in C. muytjensii strain 530 which was defined as ECA3, and a truncated rmlA2 in C. turicensis strains 1552 and 1880, these were still assigned as ECA2.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of enterobacterial common antigen (ECA) gene clusters across the Cronobacter genus

Table 2.

Serotype and capsular profiles of Cronobacter species

| Species | Number of strains | Sequence type | Clonal complex | gnd allele | galF allele | O-type | K-antigen type | Colanic acid type | Cellulose bcs genes | Enterobacterial common antigen type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. sakazakii | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | O1 | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 2 | O1 | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 5 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 4 | O1 | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 64 | 64 | 37 | 26 | O2 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 12 | 24 | 22 | O3 | K2 | CA1 | + | ECA1 | |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 31 | 31 | 29 | 26 | O2 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 2 | 3 | 3 | 20 | 18 | O2 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 34 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | O2 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 4 | 15 | 4 | 2 | 3 | O2 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 218 | 4 | 2 | 3 | O2 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 4 | 4 | 14 | 13 | O4 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 7 | 12 | 14 | 13 | O4 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA1 | |

| C. sakazakii | 2 | 40 | 45 | 14 | 13 | O4 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 5 | 13 | 13 | 28 | 25 | O2 | K2 | CA2 | CL- | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 100 | 100 | 13 | 1 | O1 | K2 | CA1 | CL- | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 125 | 100 | 13 | 1 | O1 | K2 | CA1 | CL- | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 148 | 16 | 23 | 21 | O1 | K2 | CA1 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 257 | 21 | 21 | 19 | O1 | K2 | CA1 | + | ECA1 |

| C. sakazakii | 1 | 297 | 18 | 17 | O1 | K2 | CA1 | + | ECA1 | |

| C. malonaticus | 1 | 307 | 112 | 33 | 6 | O1 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA2 |

| C. malonaticus | 2 | 60 | 27 | 24 | O1 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. malonaticus | 4 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | O2 | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA2 |

| C. malonaticus | 1 | 84 | 7 | 4 | 5 | O2 | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA2 |

| C. malonaticus | 2 | 302 | 36 | 32 | O2 | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. malonaticus | 1 | 129 | 129 | 26 | 23 | O2 | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA2 |

| C. malonaticus | 1 | 11 | 5 | 6 | O3 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA1 | |

| C. malonaticus | 1 | 300 | 300 | 38 | 24 | O3 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 |

| C. turicensis | 1 | 19 | 24 | 8 | 9 | O1 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 |

| C. turicensis | 1 | 5 | 6 | 7 | O4 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. turicensis | 1 | 344 | 34 | 30 | O3 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. turicensis | 1 | 72 | 72 | 30 | 27 | O3 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 |

| C. turicensis | 1 | 35 | 22 | 20 | O3 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. turicensis | 1 | 342 | 31 | 28 | O1 | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. dublinensis sbsp. dublinensis | 1 | 106 | 12 | 12 | O1b | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. dublinensis subsp. lactaridi | 1 | 79 | 15 | 14 | O1a | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. dublinensis sbsp. lausanensis | 2 | 80 | 80 | 11 | 11 | O2 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 |

| C. dublinensis | 1 | 36 | 80 | 11 | 11 | O2 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 |

| C. dublinensis | 1 | 346 | 25 | 11 | O2 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. dublinensis | 1 | 341 | 32 | 29 | O2 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. dublinensis | 1 | 301 | 35 | 31 | na | K2 | CA2 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. muytjensii | 1 | 347 | 10 | 10 | O3 | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. muytjensii | 1 | 81 | 81 | 16 | 15 | O2 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 |

| C. muytjensii | 1 | 294 | 17 | 16 | O1 | K1 | CA1 | + | ECA3 | |

| C. universalis | 1 | 54 | 7 | 8 | O1 | K1 | CA2 | + | ECA2 | |

| C. condimenti | 1 | 98 | 9 | 33 | O1 | K1 | CA2 | CL- | ECA2 |

Colanic acid gene cluster diversity

The colanic acid encoding gene cluster (CA) was located adjacent to the O-antigen region and separated by galF. Only two variants were found, CA1 and CA2 composed of 21 and 20 genes respectively, which differ in the presence of galE (encoding for UDP-N-acetyl glucosamine 4-epimerase) in CA1, and absence in CA2; Table 2. The occurrence of these two capsular regions varied across the genus. CA1 was found in most C. sakazakii sequence types, and other species. Whereas, CA2 was primarily found in C. sakazakii sequence types ST4 and ST12. CA2 was also found in only a few of the 14 C. malonaticus strains; 507 (ST11) and 1569 (ST307), 1846, 687 (ST60) and 2109 (ST300). CA2 was not found in any C. malonaticus ST7 strains (n = 5).

K-antigen characterisation

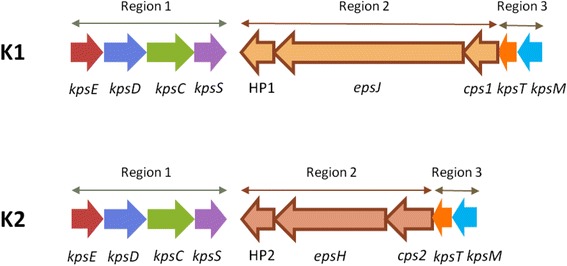

A previously uncharacterised capsular region (kps) was found in all (n = 104) Cronobacter strains and species. The region was homologous to the previously well described K-antigen gene cluster of E. coli, and which is composed of three regions. The K-antigen Region 1 (kpsEDCS) and Region 3 (kpsTM) were conserved across the genus. There were two variants of Region 2. Both variants encoded for genes for which no specific nearest matches (<50 % similarity) to specifically identified genes could be found in any BLAST search. Therefore the open reading frames are described here as either hypothetical proteins or by the general term glycosyltransferase; Table 3 and Fig. 4. The two glycosyltransferases (I and II) in Region 2 were not identical and differed in their length and GC% content; see Table 2. Region 2 GC% content of kps capsule type 1 was 42.8–46.8 %, whereas that of kps capsule type 2 was notably lower at 32.4–34.7 %. The GC content of Regions 1 and 3 was between 50–63 %. Comparison of kpsS (encoding for the capsular polysaccharide transport protein) showed there was sequence variation according to kps Region 2.

Table 3.

Cronobacter kps region 2 genes

| Kps capsule type | Kps region 2 gene | Function | Size (kb) | GC content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | hyp1 | Hypothetical protein | 1.23 | 44.9 |

| espJ | Glycosyltransferase I | 3.78 | 42.8 | |

| cps1 | Capsular polysaccharide phosphotransferase | 1.11 | 46.8 | |

| 2 | hyp2 | Hypothetical protein | 1.17 | 32.4 |

| epsH | Glycosyltransferase II | 2.28 | 34.7 | |

| cps2 | Capsular polysaccharide phosphotransferase | 1.09 | 33.8 |

Fig. 4.

Cronobacter spp. K1 and K2 Region 1–3 kps genes

Cronobacter strains with K-antigen type 1 were in all seven Cronobacter species. This included C. sakazakii sequence types ST1, ST8, ST14, ST64, C. malonaticus ST7, ST11, ST84, ST300, ST302, C. turicensis ST5, ST19, ST72, and ST344, all C. dublinensis strains except ST301, and all strains of C. condimenti, C. muytjensii and C. universalis; Table 2. Phylogenetic analysis of the glycosyltransferase I region largely reflected the whole genome phylogeny of the genus, with C. sakazakii and C. malonaticus clustering separately from C. turicensis, and C. dublinensis and C. muytjensii forming separate clusters; Fig. 5. Both C. malonaticus and C. dublinensis clusters separated into two smaller groups, reflecting the sequence types.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree of Cronobacter type 1 KPS Region 2 glycosyltransferase

The occurrence of K-antigen type 2 in the Cronobacter genus was more limited than type 1; Table 2. It was only found in C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus and C. turicensis. The main C. sakazakii sequences types with K-antigen type 2 were ST3, ST12, ST13, and those in clonal complex of ST4. The K-antigen type 2 was also found in C. malonaticus ST60 & ST307, C. turicensis ST35 & ST342 (both sialic acid utilizers), and C. dublinensis ST301. Phylogenetic analysis showed the C. sakazakii strains formed one large cluster, separate from the remaining species; Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic tree of Cronobacter type 2 KPS Region 2 glycosyltransferase

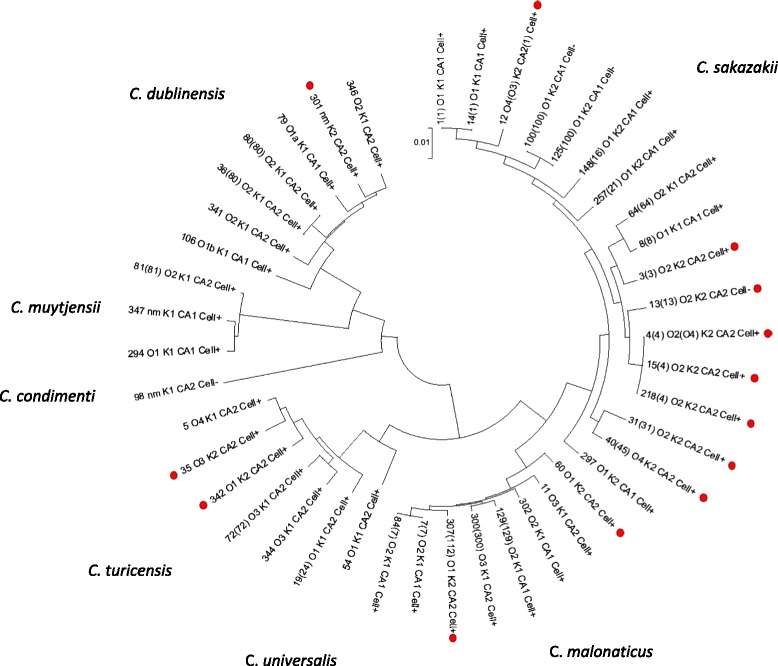

Collating the occurrence of capsular genes and isolate source detail revealed a pattern in the presence of three capsule gene clusters; K-antigen, colanic acid and cellulose biosynthesis genes. This is summarised in Table 2, and for each strain in Additional file 1: Table S4. The possession of these three genes clusters was not phylogenetically linked; Fig. 7. Strains which were K2:CA2:Cell+ were sequence types of C. sakazakii and C. malonaticus which were mostly associated with cases of neonatal meningitis and necrotising enterocolitis. These included all C. sakazakii ST3, ST12 and strains in the clonal lineage ST4, as well as C. malonaticus ST60 and ST307. C. turicensis ST35 and ST342 also had the capsular profile K2:CA2:Cell+. It should be noted that C. turicensis strains in these two STs are able to utilise sialic acid as carbon source for growth, a trait otherwise only found in C. sakazakii. Strains with the capsular profile K2:CA2 but lacking the cellulose biosynthesis genes bcs, were all in C. sakazakii ST13, and had not been isolated from serious neonatal infections. Instead they had been isolated from prepared infant formula or from stool samples of neonates with minor digestive problems or asymptomatic.

Fig. 7.

7-loci phylogenetic tree of Cronobacter genus with capsular gene profile K2:CA2 indicated (•)

Discussion

It is well recognised that bacterial cell surface structures can have a major role in pathogenicity, and can be used for typing schemes. Molecular methods for the characterisation and identification of O-antigen determinants of Gram-negative bacteria have been devised using RFLP profiling of the rfb locus as well as allele-specific PCR primers [23, 24]. The entire O-antigen encoding gene cluster can be amplified using primers that target conserved regions in the neighbouring gnd sequence and JUMPstart sequence, and enzymic digestion of this amplicon can identify RFLPs correlating to O-antigen determinants [51]. This approach was initially applied to Cronobacter by Mullane et al. [22] and expanded by other groups [23, 24]. This has led to 24 O-antigen serotypes being described across the Cronobacter genus [27]. However this approach is less discriminatory than the 7-loci MLST scheme which has >350 defined types [17]. This is probably due to several reasons. First, the targeting of genes (wzx and wzy) which are largely conserved across the genus. Second, the lack of accuracy when using gel electrophoresis of RFLP products in recognising DNA-sequence variants. This is because unique restriction profiles may not be present for all serotypes or the size of the PCR amplicons cannot be accurately resolved. These issues have previously been identified with O-serotyping of Shiga-toxigenic E. coli (STEC) [3].

Phylogenetic analysis based on wzx and wzy sequence analysis of the Cronobacter O-antigen reveals the extent to which these gene sequences are indistinguishable across different Cronobacter species; Figs. 1 and 2. The only serotypes with unique sequences within a species were C. sakazakii O2, O4 and C. dublinensis O2. In contrast some gene sequences, such as C. sakazakii O5, were indistinguishable across 5 Cronobacter species; Table 1. Some overlap of wzx and wzy genes across the Cronobacter genus has been reported before, but the extent of the issue has been more fully revealed here.

The lack of phylogeny congruence in the O-antigen has resulted in the need for prior accurate speciation of Cronobacter isolates. Although PCR probes rpoB and cgcA have been advocated to speciate presumptive Cronobacter isolates, this is no longer recommended since it is now apparent that neither method is reliable. Jackson et al. [33, 34] have reported the mis-identification of Cronobacter and non-Cronobacter strains using these methods, and also a previously reported outbreak of C. sakazakii based on rpoB PCR probe identification was re-investigated and found to be due to Enterobacter spp. and E. hormaechei instead. An alternative use of fusA allele sequencing which corresponds to whole genome phylogeny is considerably more reliable and is one of the standard 7-loci for Cronobacter MLST [14, 19]. The latter is supported by an open access database of >1000 strains and >100 whole sequenced genomes [17].

As an alternative to RFLP for serotyping STEC, Gilmour et al. [3] successfully applied gnd sequence polymorphism analysis. Consequently, the sequence polymorphisms in the O-antigen flanking genes galF and gnd were evaluated for Cronobacter strain typing. Similarly in Salmonella the O-antigen encoding rfb locus flanking gene gnd maintains high levels of polymorphism linked to the diverse rfb operon [52]. These genes follow more closely the phylogeny of the genus than wzx and wzy. The exceptions being certain sequence types of C. sakazakii and C. dublinensis, which are discussed later. This study revealed 33 and 38 distinguishable variants, respectively; Table 2, Additional file 1: Figure S1 and S2. Unfortunately not all previously published serotypes could be assigned gnd or galF alleles as the region has not been sequenced by previous researchers investigating this particular region, and no appropriate whole genomes have been released. Despite the reported lack of relationship between O-antigen and the genus phylogeny [25, 26], this study has shown the closer correlation in sequence of the O-antigen flanking genes with the phylogenetic structure of the genus as defined using whole genome sequences which correlates with sequence typing [14, 19]. It is proposed that each defined gnd or galF allele could correspond to a discrete O-PS structure, and this warrants further investigation.

C. sakazakii ST12 strains were serotype C. sakazakii O4 and formed a separate cluster outgroup with C. dublinensis ST106 from the other Cronobacter with both galF and gnd phylogenetic trees; Additional file 1: Figure S1 and S2. This group corresponds with those identified by Sun et al. [26] and Shashkov et al. [32] regarding their similarity to E. coli O103.

Strains in C. dublinensis were in two cluster groups with gnd, but not galF. Using PubMLST.org/cronobacter/ genome comparator and COG-MLST tools [17] it was noted that C. dublinensis ST106 strains in the first cluster group (nearest neighbours C. turicensis and C. muytjensii) are able to utilise malonate. In contrast, the outlier group of C. dublinensis O2 with nearest neighbour C. sakazakii ST12 do not metabolise malonate (laboratory studies data not presented). This curious distribution of genes may reflect gene loss or gain during the genus evolution and adaption.

As previously reported, C. sakazakii does not possess curli fimbriae [14]. However these are encoded in some C. malonaticus, C. turicensis and C. universalis strains. The reason for this variation is unknown, but is surprising given curli fimbriae are associated with bacterial resistance to bile salts, and C. sakazakii is an enteric pathogen. Passage through the digestive tract will expose Cronobacter cells to high concentrations of bile salts which could damage the cell membrane. The organism does grow in Enterobacteriaceae Enrichment broth and on standard Enterobacteriaceae isolation media such as VRBGA. These contain 0.3 and 0.15 % bile salts respectively, and therefore the organism possesses other resistance mechanisms to bile salts.

The ECA is important for the bacterial cell envelope integrity, flagellum expression, and resistance to bile salts [53]. It is plausible that ECA contributes to Cronobacter enteric survival by protecting the organism from bile salts, as has been proposed for Salmonella. The gene wecD is associated with bile salts resistance in Salmonella and was present in the three ECA variants. It is currently unknown what the biochemical and functional significance are for the differences in the three ECA gene clusters in Cronobacter.

The colanic acid gene cluster CA2 was primarily found in C. sakazakii sequence types ST4 and ST12. These are clinically important sequence types with respect to neonatal infections. CA2 was also found in five of the 14 C. malonaticus strains; 507 (ST11) and 1569 (ST307), 1846, 687 (ST60) and 2109 (ST300). CA2 was not in any C. malonaticus ST7 strains (n = 5), which is the sequence type predominantly associated with adult infections. The significance of this variation is discussed further with respect to the K-antigen.

Genes involved in CPS biosynthesis and transport are typically organised within a so-called capsular gene cluster. CPS transport genes are generally well conserved. The Group 2 K-antigen assembly system of E. coli has been well studied both genetically and biochemically as an ABC-transporter-dependent pathway [1, 2]. The conserved Regions 1 (kpsFEDUCS) and 3 (kpsTM) encode for the poly-KDO linker and transport proteins for initiation of chain elongation and translocation to the cell surface. Region 2 genes encode for the glycosyltransferases and other enzymes responsible for biosynthesis of the K-antigen-specific CPS. In comparison with Groups 1, 3, and 4, expression of E. coli Group 2 CPS is subject to thermoregulation (<20 °C and 37 °C) [10].

In their genomic analysis of 11 Cronobacter strains, Joseph et al. [14] were the first to note that the organism possessed a sequence type variable capsular polysaccharide encoding region (ESA_03350-59) but did not undertake any further analysis. This new study shows this uncharacterised capsular region is found in all (n = 104) Cronobacter strains and species. The region was homologous to the well described K-antigen gene cluster from E. coli and is composed of three regions. The K-antigen Region 1 (kpsEDCS) and Region 3 (kpsTM) were conserved across the genus. However, there were two variants of Region 2. Both encode for genes for which no specific nearest matches (<50 % similarity) to identifiable genes could be found in any BLAST search; Fig. 4. The glycosyltransferases genes in Region 2 differed in their length and CG % content. Presumably this reflects differences in the polysaccharide which is synthesized and exported to the cell surface, and corresponds with the differences in the kpsS sequence. The GC % content of both Region 2 gene clusters were lower than the average GC % of Cronobacter (56 %); see Table 2. The composition of the K-antigen-specific CPS is currently unknown, but could be an important virulence or environmental fitness trait. The chemical structure of the K-antigen will greatly assist in elucidating the function of the genes in Region 2.

All strains (n = 54) of C. sakazakii CC4 and ST12 strains had the capsular profile K2:CA2:Cell+. These sequence types are strongly associated with severe neonatal infections (meningitis and NEC) [13, 17–19, 54]. However strains belonging to other STs may also cause severe neonatal infection. C. sakazakii ST31 strain 1249 was a CSF isolate from a severe case of bacterial meningitis in the UK. This strain had the capsular profile K2:CA2:Cell+. It is also of particular interest that C. malonaticus ST307 strain 1569 has the capsular profile K2:CA2:Cell+. Thus it has the same capsular profile as C. sakazakii CC4, the Cronobacter pathovar for neonatal meningitis. This may be highly significant since strain 1569 it is the only recorded isolate from a fatal meningitis neonatal case due to C. malonaticus [54]. In contrast, C. malonaticus ST7 is the most frequently isolated C. malonaticus sequence type, and is associated with adult infections [17, 55, 56]. As shown in Table 2, C. malonaticus ST7 strains have the capsular profile K1:CA1:Cell+; Fig. 7. C. turicensis strains in ST35 and ST342 also had the capsular profile K2:CA2:Cell+. Although these specific strains are non-clinical in original, it is of interest that these strains are able to utilize sialic acid as a carbon source, an ability which is otherwise limited to C. sakazakii. Such metabolism could be significant virulence trait given the sugars occurrence in breast milk, infant formula, mucin and gangliosides [57].

C. sakazakii ST13 strains had the profile K2:CA2:Cell−, since they lack the cellulose biosynthesis bcs genes. These strains had been isolated from the stools of two infants and three prepared infant formula feeds during a NICU C. sakazakii ST4 outbreak, but no severe infections were reported in these particular infants other than a minor digestive problem in one of them [42]. Further research is required to elucidate the possible roll of bacterial cellulose with pathogenesis. C. sakazakii ST64 strains are K1:CA2:Cell+, varying from the neonatal associated capsular profile by the K-antigen. This sequence type is not associated with clinical cases, and yet has been often isolated from powdered infant formula and the environment of manufacturing plants in Switzerland, China, France, Czech Republic, and Germany [17, 45–48]. Therefore it is plausible that the possession of K2 and CA2 may give combined favourable phenotype for desiccation persistence and virulence such as serum resistance of macrophage survival, resulting in an increased risk of neonatal infection.

Phylogenetic analysis based on the sequence type (3036 nt concatenated length) for the occurrence of the capsule gene clusters for the K-antigen, colanic acid and cellulose biosynthesis showed the capsular profile of K2:CA2:Cell+ was not phylogenetically localised. While there was an expected high number of C. sakazakii clonal complex 4 STs with the trait, due to over-representation in whole genome sequenced strains, the capsular profile was also found in distantly related C. sakazakii sequence types (ie. ST12, ST31 & ST45), as well as C. malonaticus, C. turicensis, and C. dublinensis. These three species are frequently isolated from clinical cases of Cronobacter infection. The proposed capsular profiling of Cronobacter may direct new understanding of the environmental persistence and virulence traits in this organism, and warrants further investigation with respect to chemical analysis of capsular material and a more robust DNA sequence-based typing scheme which harmonises previous conflicting O-antigen analysis.

Methods

Bacterial strains

A total of 104 genomes were analysed for this study, which were the total number of genomes available (July 2015). Relevant information such as sequence type, source and year of isolation is given in Additional file 1: Table S1. Additional metadata can be obtain from the open access Cronobacter PubMLST database; http://pubmlst.org/cronobacter/.

DNA sequences

Whole genome DNA sequences collated at http://pubmlst.org/cronobacter/ were investigated. In silico analyses were carried out using search options, such as BLAST, on the Cronobacter PubMLST portal accessible at: http://pubmlst.org/perl/bigsdb/bigsdb.pl?db=pubmlst_cronobacter_isolates.

O-antigen gene regions

For comparative purposes, published Cronobacter O-antigen sequences were downloaded from Genbank; Additional file 1: Table S2.

Gnd and galF allele allocation

DNA sequences of gnd (501 bp, positions 114–614) and galF (501 bp, positions 376–876) were assigned novel alleles numbers using the Cronobacter PubMLST database by its curator (SJF).

DNA annotation and visualisation tools

Bacterial DNA sequences were investigated using the genome browser and annotation tool Artemis [58].

Phylogenetic analysis

DNA sequences were carefully curated prior to and after alignment and phylogenetic analyses in order to maximise the quality of the results using the satisfactory default parameters for the latter analyses. DNA sequences were aligned in MEGA version 5.2 using the ClustalW algorithm [59] set to default parameters settings.

The phylogenetic trees were generated using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method based on the Tamura-Nei model with the additional parameters set to default settings. All phylogenetic trees are drawn to scale with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site.

Ethics statement

All clinical data are taken from a previous publications associated with the sequenced bacterial strains.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank Nottingham Trent University for their financial support. This publication made use of the Cronobacter Multi Locus Sequence Typing website (http://pubmlst.org/cronobacter/) developed by Keith Jolley and sited at the University of Oxford (Jolley & Maiden [50]). The development of this site has been funded by the Wellcome Trust. The authors thank our numerous collaborators especially those involved who have submitted sequences to the Cronobacter PubMLST database.

Abbreviations

- BIGSdb

Bacterial Isolate Genome Sequence database

- CC

Clonal complex

- CPS

Capsular polysaccharides

- ECA

Enterobacterial common antigen

- EPS

Exopolysaccharides

- MLST

Multilocus sequence typing

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- NM

Non-motile

- PCR

Polymerase chain reactions

- PIF

Powdered infant formula

- RFLP

Random fragment length polymorphism

- ST

Sequence type

- STEC

Shiga-toxigenic E. coli

Additional file

Summary of strains with source details from Cronobacter PubMLST database. Table S2. Genbank accession numbers used for O-antigen loci. Table S3. Description of C. muytjensii O-antigen designations. Table S4. Serotype and capsular profiles of Cronobacter species. Figure S1. Phylogenetic tree of Cronobacter spp. galF sequences (total length 501 bp). Figure S2. Phylogenetic tree of Cronobacter spp. gnd sequences (total length 501 bp). (DOC 292 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PO: performed the genomic analysis. SF: Initiated the study, wrote the manuscript, and managed the project. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Willis LM, Whitfield C. Structure, biosynthesis, and function of bacterial capsular polysaccharides synthesized by ABC transporter-dependent pathways. Carbohydrate Res. 2013;378:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitfield C. Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:39–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmour MW, Olson AB, Andrysiak AK, Ng L-K, Chui L. Sequence-based typing of genetic targets encoded outside of the O-antigen gene cluster is indicative of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli serogrouping lineages. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:620–628. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danese PN, Pratt LA, Kolter R. Exopolysaccharide production is required for development of Escherichia coli K-12 biofilm architecture. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3593–3596. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.12.3593-3596.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehall JR, Kite CA, Saltzman DA, Wallett T, Jackson RJ, Smith SD. Prospective study of the incidence and complications of bacterial contamination of enteral feeding in neonates. J Ped Surg. 2002;37:1177–1182. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.34467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kajimura J, Rahman A, Rick PD. Assembly of cyclic enterobacterial common antigen in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6917–6927. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.6917-6927.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels DL, Plunkett G, III, Burland V, Blattner FR. Analysis of the Escherichia coli genome: DNA sequence of the region from 84.5 to 86.5 min. Science. 1992;257:771–778. doi: 10.1126/science.1379743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman A, Barr K, Rick PD. Identification of the structural gene for the TDP-Fuc4NAc:Lipid II Fuc4NAc transferase involved in synthesis of enterobacterial common antigen in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6509–6516. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6509-6516.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zogaj X, Bokranz W, Nimtz M, Römling U. Production of cellulose and curli fimbriae by members of the Family Enterobacteriaceae isolated from the human gastrointestinal tract. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4151–4158. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.4151-4158.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navasa N, Rodrıguez-Aparicio LB, Ferrero MA, Moteagudo-Mera A, Martınez-Blanco H. Growth temperature regulation of some genes that define the supercial capsular carbohydrate composition of Escherichia coli K92. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;320:135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holy O, Forsythe SJ. Cronobacter species as emerging causes of healthcare-associated infection. J Hosp Infect. 2014;86:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alzahrani H, Winter J, Boocock D, Girolamo L, Forsythe S. Characterisation of outer membrane vesicles from a neonatal meningitic strain of Cronobacter sakazakii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2015, In Press. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv085. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Joseph S, Forsythe S. Predominance of Cronobacter sakazakii sequence type 4 in neonatal infections. Emerg Inf Dis. 2011;17:1713–1715. doi: 10.3201/eid1709.110260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joseph S, Desai P, Ji Y, Cummings CA, Shih R, Degoricija L, et al. Comparative analysis of genome sequences covering the seven Cronobacter species. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Townsend SM, Hurrell E, Gonzalez-Gomez I, Lowe J, Frye JG, Forsythe S, et al. Enterobacter sakazakii invades brain capillary endothelial cells, persists in human macrophages influencing cytokine secretion and induces severe brain pathology in the neonatal rat. Microbiology. 2007;153:3538–3547. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Townsend SM, Hurrell E, Forsythe S. Virulence studies of Enterobacter sakazakii isolates associated with a neonatal intensive care unit outbreak. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forsythe SJ, Dickins B, Jolley KA. Cronobacter, the emergent bacterial pathogen Enterobacter sakazakii comes of age; MLST and whole genome sequence analysis. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph S, Forsythe SJ. Insights into the emergent bacterial pathogen Cronobacter spp., generated by multilocus sequence typing and analysis. Front Food Microbiol. 2012;3:397. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joseph S, Sonbol H, Hariri S, Desai P, McClelland M, Forsythe SJ. Diversity of the Cronobacter genus as revealed by multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3031–3039. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00905-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kucerova E, Joseph S, Forsythe S. Cronobacter: diversity and ubiquity. Qual Ass Safety Foods Crops. 2011;3:104–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-837X.2011.00104.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kucerova E, Clifton SW, Xia X-Q, Long F, Porwollik S, Fulton L, et al. Genome sequence of Cronobacter sakazakii BAA-894 and comparative genomic hybridization analysis with other Cronobacter species. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullane N, O’Gaora P, Nally JE, Iversen C, Whyte P, Wall PG, et al. Molecular analysis of the Enterobacter sakazakii O-antigen gene locus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:3783–3794. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02302-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarvis KG, Grim CJ, Franco AA, Gopinath G, Sathyamoorthy V, Hu L, et al. Molecular characterization of Cronobacter lipopolysaccharide O-antigen gene clusters and development of serotype-specific PCR assays. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:4017–4026. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00162-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, Wang M, Liu H, Wang J, He X, Zeng J, et al. Development of an O-antigen serotyping scheme for Cronobacter sakazakii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2209–2214. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02229-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarvis KG, Yan QQ, Grim CJ, Power KA, Franco AA, Hu L, et al. Identification and characterization of five new molecular serogroups of Cronobacter spp. Foodborne Path Dis. 2013;10:343–352. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Wang M, Wang Q, Cao B, He X, Li K, et al. Genetic analysis of the Cronobacter sakazakii O4 to O7 O-antigen gene clusters and development of a PCR assay for identification of all C. sakazakii O-serotypes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:3966–3974. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07825-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blažková M, Javůrková B, Vlach J, Göselová S, Ogrodzki P, Forsythe S, et al. Diversity of O-antigen designations within the genus Cronobacter: from disorder to order. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:5574–5582. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00277-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arbatsky NP, Wang M, Shashkov AS, Chizhov AO, Feng L, Knirel YA, et al. Structure of the O-polysaccharide of Cronobacter sakazakii O2 with a randomly O-acetylated l-rhamnose residue. Carbohydr Res. 2010;345:2090–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Czerwicka M, Forsythe SJ, Bychowska A, Dziadziuszko H, Kunikowska D, Stepnowski P, et al. Structure of the O-polysaccharide isolated form Cronobacter sakazakii 767. Carbohydr Res. 2010;345:908–913. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacLean LL, Pagotto F, Farber JM, Perry MB. Structure of the antigenic repeating pentasaccharide unit of the LPS O-polysaccharide of Cronobacter sakazakii implicated in the Tennessee outbreak. Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:459–465. doi: 10.1139/O09-004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacLean LL, Vinogradov E, Pagotto F, Farber JM, Perry MB. The structure of the O-antigen of Cronobacter sakazakii HPB 2855 isolate involved in a neonatal infection. Carbohydr Res. 2010;345:1932–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shashkov AS, Wang M, Turdymuratov EM, Hu S, Arbatsky NP, Guo X, et al. Structural and genetic relationships of closely related O-antigens of Cronobacter spp. and Escherichia coli: C. sakazakii G2594 (serotype O4)/E. coli O103 and C. malonaticus G3864 (serotype O1)/E. coli O29. Carbohydr Res. 2015;404:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson E, Sonbol H, Masood N, Forsythe SJ. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of Cronobacter species, with particular attention to the newly reclassified species C. helveticus, C. pulveris, and C. zurichensis. Food Microbiol. 2014;44:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson EE, Parra Flores J, Fernandez-Escartin E, Forsythe SJ. Re-evaluation of a suspected Cronobacter sakazakii outbreak in Mexico. J Food Protect. 2015;78:1191–1196. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hurrell E, Kucerova E, Loughlin M, Caubilla-Barron J, Hilton A, Armstrong R, et al. Neonatal enteral feeding tubes as loci for colonisation by members of the Enterobacteriaceae. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurrell E, Kucerova E, Loughlin M, Caubilla-Barron J, Forsythe SJ. Biofilm formation on enteral feeding tubes by Cronobacter sakazakii, Salmonella serovars and other Enterobacteriaceae. Intl J Food Microbiol. 2009;136:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iversen C, Forsythe SJ. Risk profile of Enterobacter sakazakii, an emergent pathogen associated with infant milk formula. T Food Sci Tech. 2003;11:443–454. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2244(03)00155-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iversen C, Lane M, Forsythe SJ. The growth profile, thermotolerance and biofilm formation of Enterobacter sakazakii grown in infant formula milk. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2004;38:378–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim H, Ryu J-H, Beuchat LR. Attachment and biofilm formation by Enterobacter sakazakii on stainless steel and enteral feeding tubes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;73:5846–5856. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00654-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dancer GI, Mah JH, Kang DH. Influences of milk components on biofilm formation of Cronobacter spp. (Enterobacter sakazakii) Lett Appl Microbiol. 2009;48:718–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheepe-Leberkühne M, Wagner F. Optimization and preliminary characterization of an exopolysaccharide synthezised by Enterobacter sakazakii. Biotech Lett. 1986;8:695–700. doi: 10.1007/BF01032564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caubilla-Barron J, Hurrell E, Townsend S, Cheetham P, Loc-Carrillo C, Fayet O, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of Enterobacter sakazakii strains from an outbreak resulting in fatalities in a neonatal intensive care unit in France. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3979–3985. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01075-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris LS, Oriel PJ. Heteropolysaccharide production by Enterobacter sakazakii. US Patent. 1989;4:806–836. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehner A, Riedel K, Eberl L, Breeuwer P, Diep B, Stephan R. Biofilm formation, extracellular polysaccharide production, and cell-to-cell signaling in various Enterobacter sakazakii strains: aspects promoting environmental persistence. J Food Protect. 2005;68:2287–2294. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-68.11.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fei P, Man C, Lou B, Forsythe S, Chai Y, Li R, et al. Genotyping and source tracking of the Cronobacter sakazakii and C. malonaticus isolated from powdered infant formula and an infant formula production factory in China. Appl Env Microbiol. 2015. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Muller A, Stephan R, Fricker-Feer C, Lehner A. Genetic diversity of Cronobacter sakazakii isolates collected from a Swiss infant formula production facility. J Food Protect. 2013;76:883–887. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Power KA, Yan Q, Fox EM, Cooney S, Fanning S. Genome sequence of Cronobacter sakazakii SP291, a persistent thermotolerant isolate derived from a factory producing powdered infant formula. Genome Announc. 2013;1:13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00082-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sonbol H, Joseph S, McAuley C, Craven H, Forsythe SJ. Multilocus sequence typing of Cronobacter spp. from powdered infant formula and milk powder production factories. Intl Dairy J. 2013;30:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2012.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caubilla-Barron J, Forsythe S. Dry stress and survival time of Enterobacter sakazakii and other Enterobacteriaceae. J Food Protect. 2007;70:2111–2117. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.9.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jolley KA, Maiden MC. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hobbs M, Reeves PR. The JUMPstart sequence: a 39 bp element common to several polysaccharide gene clusters. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:855–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butela K, Lawrence J. Population genetics of Salmonella: selection for antigenic diversity. In: Robinson DA, Falush D, Feil EJ, editors. Bacterial population genetics in infectious disease. UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramos-Morales F, Prieto AI, Beuzón CR, Holden DW, Casadesús J. Role for Salmonella enterica enterobacterial common antigen in bile resistance and virulence. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:5328–5332. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.17.5328-5332.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hariri S, Joseph S, Forsythe SJ. Cronobacter sakazakii ST4 strains and neonatal meningitis, US. Emerg Inf Dis. 2013;19:175–177. doi: 10.3201/eid1901.120649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holy O, Petrzelova J, Hanulik V, Chroma M, Matouskova I, Forsythe SJ. Epidemiology of Cronobacter spp. isolates from hospital patients from the University Hospital Olomouc (Czech Republic) Epidemiol Mikrobiol Immunol. 2014;63:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alsonosi A, Hariri S, Kajsík M, Oriešková M, Hanulík V, Röderová M, et al. The speciation and genotyping of Cronobacter isolates from hospitalised patients. Euro J Clin Infect Microbiol 2015. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Joseph S, Hariri S, Masood N, Forsythe S. Sialic acid utilization by Cronobacter sakazakii. Microbial Inform Exptn. 2013;3:3. doi: 10.1186/2042-5783-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carver T, Harris SR, Berriman M, Parkhill J, McQuillan JA. Artemis: an integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:464–469. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar S, Tamura K, Jakobsen IB, Nei M. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1244–1245. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]