Abstract

Background: In the phase 3 DEFINE and CONFIRM trials, flushing and gastrointestinal (GI) events were associated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF; also known as gastroresistant DMF) treatment in people with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). To investigate these events, a post hoc analysis of integrated data from these trials was conducted, focusing on the initial treatment period (months 0−3) with the recommended DMF dosage (240 mg twice daily).

Methods: Eligibility criteria included age 18 to 55 years, relapsing-remitting MS diagnosis, and Expanded Disability Status Scale score 0 to 5.0. Patients were randomized and received treatment with placebo (n = 771) or DMF (n = 769) for up to 2 years. Adverse events were recorded at scheduled clinic visits every 4 weeks.

Results: The incidence of GI and flushing events was highest in the first month of treatment. In months 0 to 3, the incidence of GI events was 17% in the placebo group and 27% in the DMF group and the incidence of flushing and related symptoms was 5% in the placebo group and 37% in the DMF group. Most GI and flushing events were of mild or moderate severity and resolved during the study. The events were temporally associated with the use of diverse symptomatic therapies (efficacy not assessed) and infrequently led to DMF discontinuation.

Conclusions: This integrated analysis indicates that in a clinical trial setting, GI and flushing events associated with DMF treatment are generally transient and mild or moderate in severity and uncommonly lead to treatment discontinuation.

When choosing among treatments for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), health-care providers and patients must weigh factors such as efficacy, safety, tolerability, and convenience. Newer therapeutics are attractive owing to their convenience, but the current lack of long-term experience with these agents may limit their use compared with traditional agents with well-established safety and tolerability profiles.

Delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF; also known as gastroresistant DMF) is one of the newest oral therapeutics. In the phase 3 DEFINE (Determination of the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Fumarate in Relapsing-Remitting MS)1 and CONFIRM (Comparator and an Oral Fumarate in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis)2 trials, DMF 240 mg twice daily and three times daily demonstrated efficacy on clinical and neuroradiologic measures across diverse subgroups of patients.3,4 The most common adverse events associated with DMF treatment were flushing and gastrointestinal (GI) events, including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Other safety signals of note included decreases in mean white blood cell and lymphocyte counts and transient elevations in mean liver enzyme levels. There was no overall increased risk of infections, serious infections, opportunistic infections, or malignancies in DMF-treated patients.

Flushing and GI events are likely to be of concern when considering treatment with DMF. To further investigate the incidence, severity, duration, management, and outcome of these events as recorded by investigators at monthly clinic visits, a post hoc analysis of integrated data from DEFINE and CONFIRM was conducted. The analysis focused on the initial treatment period (months 0−3) with the recommended dosing regimen of DMF (240 mg twice daily).

Materials and Methods

Patients and Study Design

Methodological details of the phase 3 DEFINE (NCT00420212) and CONFIRM (NCT00451451) studies have been described previously.1,2 Briefly, eligible patients were aged 18 to 55 years, had a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS per the McDonald criteria5 and an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score6 of 0 to 5.0, and had either 1 or more clinically documented relapses within 1 year before randomization and a previous cranial magnetic resonance image showing lesions consistent with MS or a brain magnetic resonance image obtained within 6 weeks before randomization showing at least one gadolinium-enhancing lesion.

DEFINE and CONFIRM were 2-year, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. In DEFINE, patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive placebo, DMF 240 mg twice daily, or DMF 240 mg three times daily (408, 410, and 416 patients, respectively, in the safety population, defined as patients who received at least one dose of study treatment) for up to 96 weeks. In CONFIRM, patients were randomized 1:1:1:1 to receive treatment with placebo, DMF 240 mg twice or three times daily, or glatiramer acetate (a reference comparator; safety population = 363, 359, 344, and 351 patients, respectively) for up to 96 weeks.

All patients provided written informed consent. The studies were approved by central and local ethics committees and were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice7 and the Declaration of Helsinki.8

Safety and Tolerability Assessments

Adverse events and concomitant medications were recorded by investigators at scheduled clinic visits occurring every 4 weeks. All adverse events were noted regardless of severity or possible relation to study treatment. Use of symptomatic therapy and dose reduction for 1 month were permitted to manage tolerability issues. No specific symptomatic therapy was recommended in the protocol.

Statistical Analyses

Tolerability parameters were summarized using descriptive statistics. Because the focus was on DMF 240 mg twice daily, data from patients treated with DMF 240 mg three times daily or glatiramer acetate were not included in the analysis.

Gastrointestinal events were defined by preferred terms in the level 2 subordinate Standardised Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Queries “gastrointestinal nonspecific inflammations” and “gastrointestinal nonspecific symptoms and therapeutic procedures.” An expanded definition of flushing was used to capture events related to flushing and included the preferred terms flushing, hot flush, erythema, generalized erythema, burning sensation, skin burning sensation, feeling hot, and hyperemia.

Management of common GI events (abdominal pain, upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) and flushing events (flushing and hot flush) with symptomatic therapy was evaluated by manual review of concomitant medications that were temporally associated with and noted by the investigator to be treatments for those events. The efficacy of the symptomatic medications was not assessed. Although the incidence of GI and flushing events is highest in the first month after DMF initiation,1,2 the integrated analysis focused on months 0 to 3 to enrich the data set on symptomatic therapy use.

The duration of common GI and flushing events was determined from the start and end dates reported by the study investigators and was calculated only for resolved events with recorded start and end dates.

Results

Study Population

The integrated data set for the analysis of GI and flushing events included 1540 patients (safety population) who were randomized and received treatment with placebo (n = 771) or DMF 240 mg twice daily (n = 769). The mean duration of exposure to study treatment (76.7 and 76.6 weeks) and mean time on study (85.7 and 84.0 weeks) were similar in the placebo and DMF groups, respectively. A comparable percentage of patients in the placebo (65%) and DMF (70%) groups completed 2 years of study treatment. Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were generally well balanced across treatment groups and were consistent with the general MS patient population, as reported elsewhere.1,2

GI Events

2-Year Study Period

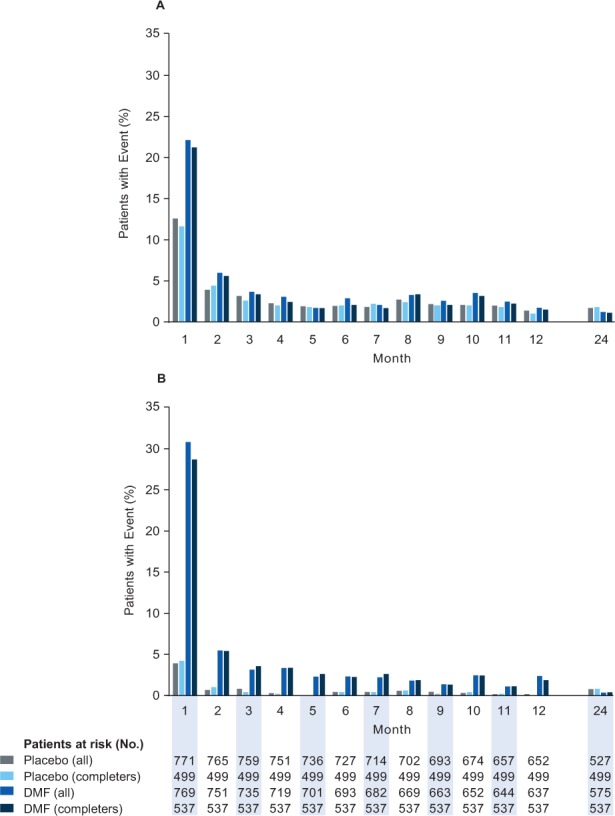

Across the 2-year study period, the incidence of GI events was 31% in the placebo group and 40% in the DMF group. The incidence was highest in the first month of treatment and declined substantially thereafter, remaining low for the duration of the study (Figure 1A). The incidence of common GI events in the placebo group versus the DMF group was as follows: abdominal pain, 5% versus 9%; upper abdominal pain, 6% versus 10%; nausea, 9% versus 12%; vomiting, 5% versus 8%; and diarrhea, 11% versus 14%. The incidence of serious GI events was less than 1% in the placebo and DMF groups.

Figure 1.

Gastrointestinal (GI) events and flushing and related symptoms: incidence by 1-month intervals

For GI (A) and flushing (B) events, the subset of patients who completed the study (completers) was comparable with the overall safety population (all) at all time points. DMF, delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (also known as gastroresistant DMF).

Patients infrequently discontinued study treatment owing to GI events (<1% in the placebo group and 3% in the DMF group). The incidence of discontinuation due to common GI events in the placebo group versus the DMF group was as follows: abdominal pain, 0% versus less than 1%; upper abdominal pain, less than 1% versus less than 1%; nausea, 0% versus less than 1%; vomiting, 0% versus 1%; and diarrhea, less than 1% versus less than 1%. Symptomatic treatments for GI events were used by 14% of patients in the placebo group and 19% of patients in the DMF group. Patients who completed the study were comparable with the overall safety population in terms of the incidence of GI events and symptomatic treatment use for GI events.

Initial Treatment Period (Months 0–3)

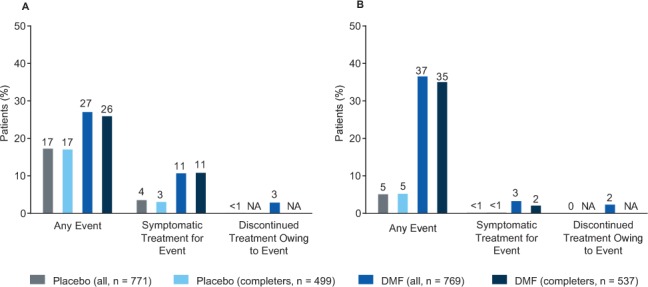

In months 0 to 3, the incidence of GI events was 17% in the placebo group and 27% in the DMF group (Figure 2A). The incidence of common GI events in the placebo group versus the DMF group was as follows: abdominal pain, 3% versus 7%; upper abdominal pain, 3% versus 7%; nausea, 5% versus 9%; vomiting, 2% versus 5%; and diarrhea, 5% versus 9%. No serious GI events were reported in either treatment group during the initial treatment period.

Figure 2.

Gastrointestinal (GI) events and flushing and related symptoms in the initial treatment period: incidence, symptomatic treatment, and discontinuation of study drug

A, Percentages of patients who experienced any GI event during the initial treatment period (months 0−3) and used symptomatic treatment for GI events or discontinued study treatment due to GI events at any time during the 2-year study. B, Percentages of patients who experienced flushing or related symptoms during the initial treatment period (months 0−3) and used symptomatic treatment for flushing or related symptoms or discontinued study treatment due to flushing or related symptoms at any time during the 2-year study. For all measures, the subset of patients who completed the study (completers) was comparable with the overall safety population (all). DMF, delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (also known as gastroresistant DMF); NA, not applicable.

A small percentage of patients experienced GI events during months 0 to 3 and discontinued study treatment owing to GI events during the 2-year study (<1% in the placebo group and 3% in the DMF group) (Figure 2A). The percentages of patients who experienced GI events during months 0 to 3 and used symptomatic treatment were 4% in the placebo group and 11% in the DMF group (Figure 2A). Patients who completed the study were comparable with the overall study population in terms of the incidence of and symptomatic treatment use for GI events (Figure 2A).

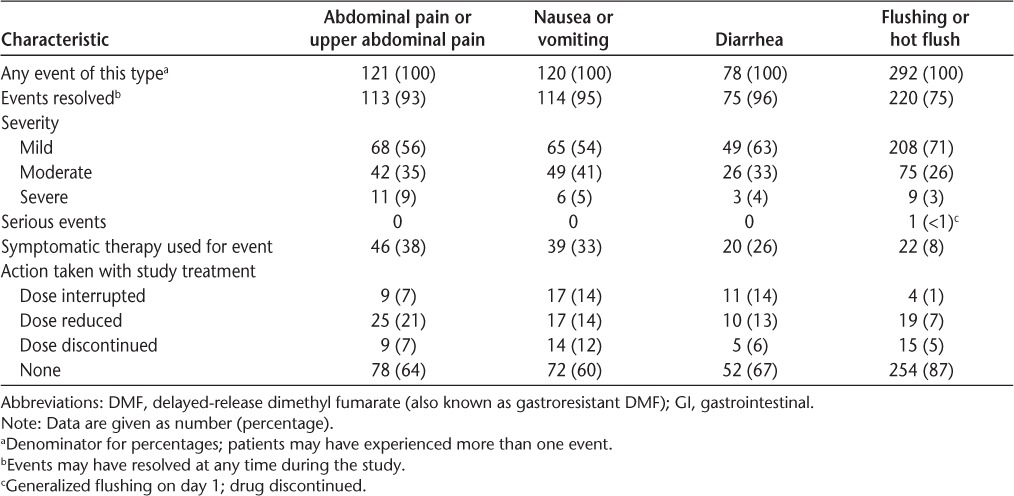

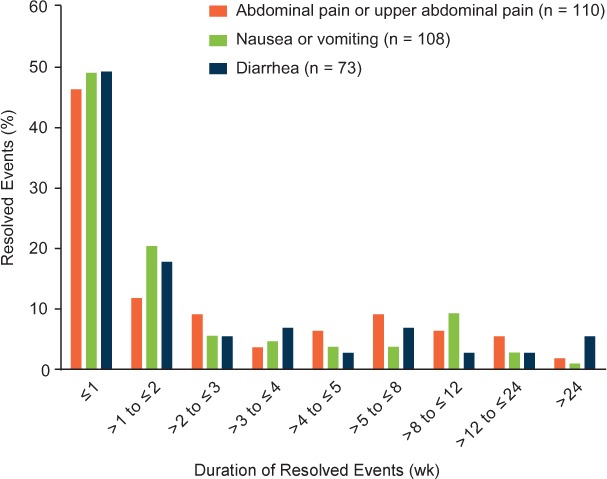

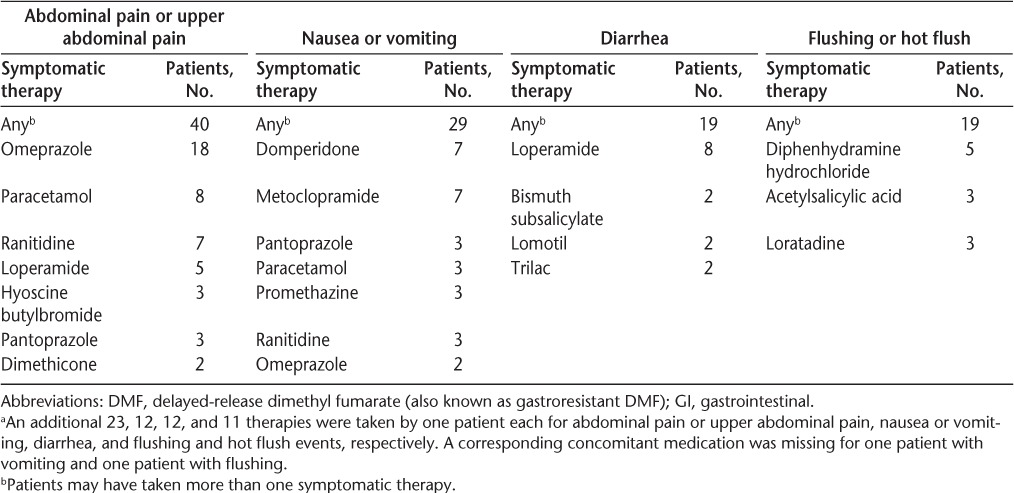

A detailed analysis of common GI events during months 0 to 3 in DMF-treated patients was conducted. A total of 121 abdominal pain or upper abdominal pain events, 120 nausea or vomiting events, and 78 diarrhea events were recorded during this period. Most of these events were of mild or moderate severity (91%−96%) and resolved during the study (93%−96%) (Table 1). The median duration of resolved events with start and end dates reported was 9.5 days for abdominal pain or upper abdominal pain, 8 days for nausea or vomiting, and 8 days for diarrhea (Figure 3). Not included in the analysis of duration were eight abdominal pain or upper abdominal pain, six nausea or vomiting, and three diarrhea events that did not resolve and three abdominal pain or upper abdominal pain, six nausea or vomiting, and two diarrhea resolved events for which end dates were missing. Common GI events were temporally associated with the use of diverse symptomatic therapies, most of which fell into the following therapeutic categories: proton pump inhibitors (abdominal pain or upper abdominal pain), gastroprokinetics (nausea or vomiting), and antidiarrheals (diarrhea) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Common GI and flushing events in the initial period of DMF treatment (months 0–3)

Figure 3.

Common gastrointestinal events (abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, and diarrhea) during the initial treatment period: duration of resolved events

Duration is reported only for resolved events with recorded start and end dates. Not included in the analysis of duration were eight abdominal pain, six nausea/vomiting, and three diarrhea events that did not resolve and three abdominal pain, six nausea/vomiting, and two diarrhea resolved events for which end dates were missing.

Table 2.

Symptomatic treatments taken by at least two patientsa for common GI and flushing events in the initial period of DMF treatment (months 0−3)

Flushing and Related Symptoms

2-Year Study Period

Across the 2-year study, the incidence of flushing and related symptoms was 8% in the placebo group and 45% in the DMF group. The incidence was highest in the first month of treatment and declined substantially thereafter, remaining low for the remainder of the 2-year study (Figure 1B). The incidence of common flushing events in the placebo group versus the DMF group was as follows: flushing, 4% versus 34%; and hot flush, 2% versus 7%. The incidence of serious flushing and related symptom adverse events was 0% in the placebo group and less than 1% in the DMF group.

Patients infrequently discontinued study treatment due to flushing and related symptoms (<1% in the placebo group and 4% in the DMF group). The incidences of discontinuation due to common flushing events in the placebo group versus the DMF group were as follows: flushing, less than 1% versus 3%; and hot flush, 0% versus less than 1%. Symptomatic treatments for flushing and related symptoms were used by less than 1% of patients in the placebo group and 5% of patients in the DMF group. Patients who completed the study were comparable with the overall study population in terms of the incidence of and symptomatic treatment use due to flushing and related symptoms.

Initial Treatment Period (Months 0−3)

In months 0 to 3, the incidence of flushing and related symptoms was 5% in the placebo group and 37% in the DMF group (Figure 2B). The incidence of common flushing events in the placebo group versus the DMF group was as follows: flushing, 3% versus 28%; and hot flush, 1% versus 5%. The incidence of serious flushing and related symptom adverse events was 0% in the placebo group and less than 1% in the DMF group.

A small percentage of patients experienced flushing and related symptoms during months 0 to 3 and discontinued study treatment due to flushing and related symptoms during the 2-year study period (0% in the placebo group and 2% in the DMF group) (Figure 2B). The percentages of patients who experienced flushing and related symptoms during months 0 to 3 and used symptomatic treatments were less than 1% in the placebo group and 3% in the DMF group (Figure 2B). Patients who completed the study were comparable with the overall study population in terms of the incidence of flushing and related symptoms and symptomatic treatment use for flushing and related symptoms (Figure 2B).

A detailed analysis of common flushing events during months 0 to 3 in DMF-treated patients was conducted. A total of 292 flushing or hot flush events were recorded during this period. Most of these events were of mild or moderate severity (97%) and resolved during the study (75%) (Table 1). The median duration of resolved flushing or hot flush events with start and end dates reported was 17.0 days for flushing and 29.0 days for hot flush. Not included in the analysis of duration were 59 flushing and 13 hot flush events that did not resolve and 18 flushing and six hot flush resolved events for which end dates were missing. Common flushing events were temporally associated with the use of symptomatic therapies, including diphenhydramine hydrochloride, loratadine, and acetylsalicylic acid (Table 2).

Discussion

In the phase 3 DEFINE and CONFIRM trials, DMF treatment was commonly associated with GI and flushing adverse events. The analysis presented herein, based on an integrated data set with more than 750 patients per group, provides a more detailed examination of these events than was possible in either study individually. Major findings concerned the incidence, severity, duration, management, and outcome of the events as recorded by investigators at monthly clinic visits. The incidence of GI events and flushing and related symptoms was highest in the first month of DMF treatment, declining thereafter. In the initial treatment period (months 0−3), common GI and flushing events were mild or moderate in severity for most patients with events. The events were temporally associated with the use of diverse symptomatic therapies, but patients infrequently discontinued treatment owing to the events.

The median duration of resolved events with recorded start and end dates was less than 2 weeks for GI events and less than 1 month for flushing and hot flush. However, it is important to note that the duration analysis has some important limitations. DEFINE and CONFIRM were not designed to examine adverse event duration as an end point, and the manner in which GI events were reported in these studies does not lend itself well to analyses of the duration of individual events. Events were reported by investigators, not by patients, and there is a lack of temporal precision in the reporting because physicians were asked only to record start and end dates. The duration analysis excluded events for which end dates were missing and events that did not resolve during the study. Unresolved events were likely not individual events but rather patients who continued to have intermittent symptoms. With these caveats in mind, the duration analyses presented herein should be considered preliminary and interpreted with caution. Additional studies designed to examine the duration of flushing and GI events, with daily self-report by individuals of event characteristics, will provide more accurate and detailed information.

In a recent survey of DEFINE and CONFIRM investigators with experience in managing GI and flushing events in DMF-treated patients, most investigators felt that it was important to manage these events, and most recommended counseling and setting expectations, taking DMF with food, and using symptomatic therapies as management strategies.9 Prospective studies examining the efficacy of putative management strategies are planned or in progress.

This integrated analysis provides valuable information for health-care providers and patients considering or initiating DMF treatment. Overall, the analysis indicates that in a clinical trial setting, GI and flushing events associated with DMF treatment were transient, mild or moderate in severity, manageable, and infrequently led to treatment discontinuation. In clinical practice, appropriate patient counseling regarding these events and use of symptomatic therapies may be effective management strategies. Further evaluation is warranted before specific management strategies can be recommended.

PracticePoints.

The incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) and flushing events is highest in the first month of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate (DMF; also known as gastroresistant DMF) treatment, declining thereafter.

The GI and flushing events associated with DMF are generally transient and mild or moderate in severity.

The GI and flushing events associated with DMF uncommonly lead to discontinuation of DMF treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the patients and investigators who were involved in the DEFINE and CONFIRM studies. Karyn M. Myers, PhD, of Biogen provided writing support based on input from authors. Biogen reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript to the authors. The authors had full editorial control of the manuscript and provided their final approval of all content. Syeda Raji, medical graphic designer at Biogen, assisted with the preparation of the figures.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Phillips has received consulting fees from Acorda, Biogen Idec, Genzyme, Merck Serono, and Sanofi; and research support from Roche. Dr. Selmaj has received compensation for consulting services from Genzyme, Novartis, Ono, Roche, Synthon, and Teva; and compensation for speaking from Biogen Idec. Dr. Gold has received honoraria from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Teva Neuroscience; and research support from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Teva Neuroscience. Dr. Fox has received consultant fees from Actelion, Biogen Idec, MedDay, Novartis, Questcor, Teva, and Xenoport; served on advisory committees for Actelion, Biogen Idec, and Novartis; and received research grant funding from Novartis. Dr. Havrdova has received honoraria from Bayer, Biogen Idec, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva. Dr. Giovannoni has received honoraria from AbbVie, Bayer HealthCare, Biogen Idec, Canbex, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, GW Pharma, Merck Serono, Novartis, Protein Discovery Laboratories, Roche, Synthon, Teva Neuroscience, UCB, and Vertex; research grant support from Biogen Idec, Ironwood, Merck Serono, Merz, and Novartis; and compensation from Elsevier as co−chief editor of MS and Related Disorders. Drs. Abourjaily, Pace, Novas, Hotermans, Viglietta, and Meltzer are employees of Biogen.

Funding/Support: This study was sponsored by Biogen.

References

- 1.Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1098–1107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1673] N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1087–1097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-Or A, Gold R, Kappos L et al. Clinical efficacy of BG-12 (dimethyl fumarate) in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: subgroup analyses of the DEFINE study. J Neurol. 2013;260:2297–2305. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6954-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutchinson M, Fox RJ, Miller DH et al. Clinical efficacy of BG-12 (dimethyl fumarate) in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: subgroup analyses of the CONFIRM study. J Neurol. 2013;260:2286–2296. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6968-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria.”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840–846. doi: 10.1002/ana.20703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Conference on Harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. ICH harmonized tripartite guideline: Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Ferney-Voltaire, France: World Medical Association; June 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips JT, Hutchinson M, Fox R, Gold R, Havrdova E. Managing flushing and gastrointestinal events associated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate: experiences of an international panel. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]