Abstract

Background

A founder variant of RNF213, p.R4810K (c.14429G>A, rs112735431), was recently identified as a major genetic risk factor for moyamoya disease (MMD) in Japan. Although the association of p.R4810K was reported to be highly significant and reproducible, the disease susceptibility of other RNF213 variants remains largely unknown. In the present study, we systematically evaluated the coding variants detected in Japanese patients and controls for associations with MMD.

Methods and Results

To detect variants of RNF213, all coding exons were sequenced in 27 Japanese MMD patients without p.R4810K. We also validated all previously reported variants in our case–control samples and tested for associations in combination with previous Japanese study cohorts, including the 1000 Genomes Project data set, as population-based controls. Forty-six missense variants other than p.R4810K were identified among 370 combined patients and 279 combined controls in Japan. Sixteen of 46 variants were polymorphisms with minor allele frequency >1%, and, after conditioning on the p.R4810K genotype, were not associated with MMD. We conducted a variable threshold test using Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion on the remaining 30 rare variants (minor allele frequency <1%), and the results showed that the frequency of potentially functional variants was significantly higher in patients than in controls (permutation, minimum P=0.045).

Conclusions

Not only p.4810K but also other functional missense variants of RNF213 conferred susceptibility to MMD. Our analysis also revealed that ≈20% of Japanese MMD patients did not harbor susceptibility variants of RNF213, indicating the presence of other susceptibility genes for MMD.

Keywords: cerebrovascular disorders, epidemiology, genetics, risk factors

Moyamoya disease (MMD) was named after its characteristic cerebral angiograms of abnormal net-like vessels that develop at the base of the brain to compensate for progressive stenosis around the carotid fork.1 This steno-occlusive condition often results in ischemic stroke, whereas a rupture of the fragile moyamoya vessels can also cause hemorrhagic stroke. Surgical revascularization is the only cure for the symptoms of MMD, such as repeated transient ischemic attack, and prevents not only subsequent ischemic attacks but also intracranial hemorrhage.2,3

The prevalence of MMD was reported to be 6 per 100 000 in the Japanese population, with 11.9% of patients being children aged <10 years.4 A family history of MMD was identified in 12.1% of patients, indicating a genetic influence in the disease etiology. Recurrence rates in siblings and offspring were also reported to be 42- and 34-fold higher, respectively, than those in the general population. The recurrence rates in relatives, however, were markedly lower than those expected from simple Mendelian inheritance, suggesting that the mode of inheritance may be multifactorial.5 Furthermore, because the prevalence of MMD is 10-fold higher in Japan than in Western countries,6 a founder mutation may exist in the Japanese population.

Based on this unique background, 2 Japanese groups successfully pinpointed RNF213 on chromosome 17q25.3 as the susceptibility gene for MMD. In these studies, most Japanese patients carried p.R4810K (c.14429G>A, rs112735431) with a significantly large effect size (190.8 to 338.9, dominant mode).7,8 The subsequent resequencing of RNF213 also identified several rare coding variants other than p.R4810K. The disease susceptibility of such rare variants remains ambiguous because very few informative pedigrees that harbor them have been reported to date.7–9 Furthermore, their biological consequences in relation to gene functions have not yet been determined, suggesting they must still be regarded as variants of unknown significance.10

Current advances in computational tools such as PolyPhen-2 (Polymorphism Phenotyping v2),11 fathmm (Functional Analysis Through Hidden Markov Models),12 and CADD (Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion)13 allow rational functional predictions of variants detected by resequencing. Furthermore, various methods for case–control association tests, especially concerning rare variants, have been proposed in combination with in silico predictions.14,15

In the present study, we extensively resequenced coding regions of RNF213 in Japanese MMD patients and controls to establish a comprehensive variant catalog of this gene in the Japanese population. Detected variants of unknown significance were classified according to their frequencies in the general population and in computed functional variables and then were systematically tested for associations with MMD.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The ethics committees of Tokyo Women’s Medical University (TWMU) and Tokyo Medical and Dental University approved the present study protocols. All participants gave written informed consent; for those considered too young to consent, informed consent was given by the parent or guardian. The DNA samples used in the present study were from 103 MMD patients (Table 1) and 190 non-MMD controls (aged 60.0±19.7 years; 76 female, 114 male). MMD was diagnosed based on the criteria of the Japanese Research Committee on Moyamoya Disease of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare16; these criteria were also detailed in the previous linkage study 17 and used in the subsequent genetic studies of MMD in Japan.7–9 The 190 unrelated controls composed 2 sample panels: 95 controls (aged 47.7±17.5 years; 44 female, 51 male) from the TWMU Hospital and 95 controls (aged 70.9±14.4 years; 32 female, 63 male) from Kofu Neurosurgical Hospital. All subjects were Japanese.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Participants With MMD in the Present Study

| Clinical Features | Participants, n (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total MMD (n=103) | p.R4810K-Positive (n=76) | p.R4810K-Negative (n=27) | ||

| Female sex | 73 (70.9) | 54 (71.1) | 19 (70.4) | 1.000 |

| Median age at onset Interquartile range | 27 years [9 to 42] | 22 years [8 to 43] | 28 years [13 to 42] | 0.332 |

| Childhood onset (<15 years) | 34 (33.0) | 27 (35.5) | 7 (25.9) | 0.476 |

| With a familial history | 27 (26.2) | 22 (28.9) | 5 (18.5) | 0.323 |

| Bilateral MMD | 78 (75.7) | 63 (82.9) | 15 (51.7) | 0.0080 |

| Clinical manifestation at onset | ||||

| Headache | 12 (11.7) | 4 (5.3) | 8 (29.6) | 0.0021 |

| Infarction/TIA | 67 (65.0) | 53 (69.7) | 14 (51.9) | 0.106 |

| ICH/IVH | 12 (11.7) | 10 (13.2) | 2 (7.4) | 0.728 |

| Others | 12 (11.7) | 9 (12.5) | 3 (11.1) | 1.000 |

| Surgical treatment | 86 (83.5) | 62 (81.6) | 24 (88.9) | 0.549 |

| Unilateral | 46 (44.6) | 33 (44.4) | 13 (48.1) | 0.822 |

| Bilateral | 40 (38.8) | 29 (38.2) | 11 (40.7) | 0.822 |

Differences in clinical characteristics were assessed by Fisher’s exact test, except for age at onset, which was assessed by Wilcoxon rank sum test. ICH indicates intracerebral hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; MMD, moyamoya disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Variant Detection of RNF213

In the present study, we referred to NM_001256071.1 as the reference transcriptional sequence of RNF213 in the GRCh37 (hg19) coordinate. Prior to the resequencing analysis, we genotyped p.R4810K in our 103 MMD patients and identified 27 patients without this variant. We then performed polymerase chain reaction amplification of all coding exons and exon–intron boundaries in these 27 patients, followed by direct sequencing. The primer sequences are provided in the supplemental Data S1 (Table S1). We also mined all previously reported nonsynonymous variants of this gene from previous Japanese studies on MMD.7–9 To eliminate an observation bias caused by searching only diseased subjects, the phase III genotypic data of 89 Japanese subjects (referred to as the JPT panel) from the 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org/)18 were also added as population-based controls. The enrolled cohorts with the study flowchart are shown in Figure S1. All exons harboring any of those variants were sequenced in our residual 76 MMD patients with p.R4810K and 190 controls (TWMU and Kofu Neurosurgical Hospital panels) to estimate their genotypic frequencies or to find novel variants. Direct sequencing was performed using BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing on a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies).

Statistical Analysis

At the p.R4810K locus, a meta-analysis was performed to combine the present and previous Japanese studies, assuming a fixed-effects model.7–9 Heterogeneity across the studies was evaluated using the I2 heterogeneity index.

Among the detected single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with minor allele frequency (MAF) >1% in the controls, we performed exact tests of the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.19 Linkage disequilibrium between pairs of SNPs was calculated using the standard definition of D′20 and was visualized using GOLD (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/GOLD/).21 Phased haplotypes were inferred using BEAGLE version 3.3.2.22 Associations with MMD were evaluated by fitting a logistic regression model with an additive effect of the allele dosage. A condition analysis was also performed for each SNP, adding the allele dosage for p.R4810K as a covariate.

To test the associations of rare nonsynonymous variants (MAF <1% in the controls), we pooled all Japanese subjects used for coding variant detection.7,9,18 We conducted the variable threshold (VT) test14,15 with slight modifications on pooled Japanese subjects, composed of 370 MMD patients and 279 controls (Figure S1). The original VT test proposed by Price et al assumes that there exists a yet-unknown MAF threshold on a given genetic region that corresponds to the cutoff for disease causality.14 This assumption is based on a tentative theory that rarer variants are more likely to be functional as a consequence of purifying selection. When optimizing the MAF threshold, the incorporation of computational predictions of mutational effects was also proposed to improve the statistical power.14,15 In contrast, we set variables for our VT test as computed functional scores of variants instead of MAFs because the original VT test proposed to analyze thousands of samples of complex traits to obtain varied allele frequencies; however, MMD is too rare to expect a large sample size, resulting in the majority of variants detected being singletons. To functionally score the variants detected, we used scaled C-scores of CADD.13 Annotations were obtained from dbNSFP v2.4.23,24 The proposed VT test using CADD was performed as follows: Mutation carriers with C-scores above a given threshold were counted in the patient and control groups, respectively. The difference in such carrier frequencies was then compared using Fisher’s exact test. After these comparisons had been repeated across all possible C-score thresholds, the empirical threshold was obtained in which the minimum P value (Pmin) was observed. The significance of the empirical threshold was accessed by permutations on phenotypes to correct multiple comparisons. We defined a permutation Pmin value as (k0+1)/(k+1), in which k is the total number of permutations and k0 is the number of permutations with Pmin lower than the original Pmin. In the present study, 1000 permutations were used. The proposed computational algorithm was similar to that of the extended VT test provided in Variant Association Tools developed by Wang et al15 (http://varianttools.sourceforge.net/Association/VariableThresholds). We also performed the functional assessments of candidate rare variants detected by the proposed VT test. The detailed methods are described in Data S1.

Differences in clinical characteristics according to RNF213 genotypes were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the post hoc Steel-Dwass test and Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively, for non-normally distributed continuous characteristics, such as age at onset and the number of steno-occlusive posterior cerebral arteries.

In the present study, P<0.05 was considered significant, except for the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, for which the significance level was generally accepted as P<0.001.19

Results

Clinical and Genetic Backgrounds of Participants

Prior to exon sequencing, we genotyped p.R4810K in our 103 MMD patients and 95 TWMU controls and confirmed an association with MMD (P=1.38×10−10, odds ratio [OR] 122.4). A meta-analysis demonstrated that the association of p.R4810K was highly significant (P=2.71×10−104, OR 217) and identical across the 4 Japanese study cohorts (I2=0.00)7–9 (Figure 1). We identified 27 MMD patients without this variant from our 103 MMD patients (Table 1). Significant differences were observed in the rates of bilateral affection (P=0.0080) and onset with headache (P=0.0021) between the mutants and wild types for the p.R4810K locus; however, no significant differences were noted for other clinical characteristics, such as the rates of positive familial history and childhood onset. These results strongly suggested the existence of allelic heterogeneity in RNF213 and/or genetic heterogeneity.

Figure 1.

Association of the p.R4810K variant (c.14429G>A, rs112735431) with moyamoya disease (MMD) across 4 Japanese studies. A meta-analysis was performed assuming a fixed-effects model. Squares and horizontal lines represent odds ratios and 95% CIs for individual studies. A diamond represents the summary odds ratio estimate and 95% CIs for the meta-analyses of 4 cohorts.

Analysis of Polymorphisms in RNF213

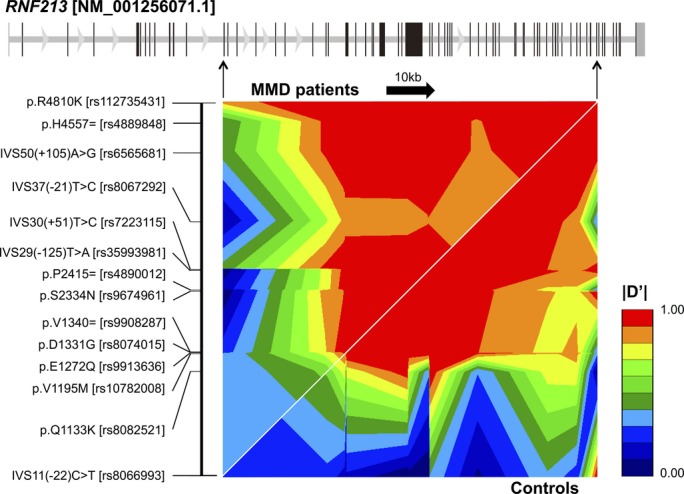

A total of 16 missense SNPs with MAF >1% were confirmed in 103 MMD patients, 95 TWMU controls, and 89 JPT subjects from the 1000 Genomes Project database18 (Table 2). No significant difference was observed in genotypic or allelic frequencies between the 95 TWMU controls and the 89 JPT subjects (P>0.05); therefore, they were combined as general population controls for the subsequent association analysis. The genotypic frequencies of all SNPs were considered to meet the Hardy-Weinberg expectations in both the patients and the combined controls (P>0.001).19 Nine SNPs were associated with MMD (P<0.05) (Table 2); however, after adjusting for the p.R4810K genotype, their association signals were completely diminished (conditional P>0.05) because of the disease-specific strong linkage disequilibrium originating from the p.R4810K alleles (Figure 2). A haplotype inference revealed 96.3% of the patients’ p.R4810K alleles carried all of the at-risk alleles of these 9 SNPs on the same haplotypes. Furthermore, these 9 at-risk alleles were identical to their ancestral alleles; conversely, their mutated alleles showed a significant protective effect. Consequently, they were all regarded as tag markers for p.R4810K susceptibility and could be excluded from further investigations.

Table 2.

Association Analysis of RNF213 SNPs Other Than the p.R4810K Variant

| Variant | dbSNP138 rs-ID | At-Risk Allele | MMD 11/12/22 (RAF) | Control 11/12/22 (RAF) | P Value | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | Conditional P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.Pro61Leu | rs9913317 | Pro | 95/8/0 (0.961) | 171/10/3 (0.956) | 0.81 | 1.10 [0.50 to 2.42] | 0.61 |

| p.Met270Thr | rs17857135 | Met | 98/5/0 (0.975) | 147/36/1 (0.896) | 0.0013 | 4.86 [1.85 to 12.7] | 0.059 |

| p.Met321Thr | rs17853989 | Met | 98/5/0 (0.975) | 148/36/0 (0.902) | 0.0016 | 4.76 [1.80 to 12.5] | 0.065 |

| p.Pro729Leu | rs72849841 | Pro | 103/0/0 (1.00) | 179/5/0 (0.986) | 1.0 | NA | 1.0 |

| p.Ala1041Thr | rs61359568 | Ala | 103/0/0 (1.00) | 169/14/1 (0.956) | 1.0 | NA | 1.0 |

| p.Gln1133Lys | rs8082521 | Gln | 80/21/2 (0.878) | 111/60/13 (0.766) | 0.0023 | 2.09 [1.30 to 3.37] | 0.98 |

| p.Val1195Met | rs10782008 | Val | 71/29/3 (0.830) | 89/74/21 (0.684) | 0.00035 | 2.16 [1.41 to 3.31] | 0.31 |

| p.Glu1272Gln | rs9913636 | Glu | 70/30/3 (0.825) | 100/71/13 (0.736) | 0.017 | 1.68 [1.09 to 2.6] | 0.77 |

| p.Asp1331Gly | rs8074015 | Asp | 69/29/5 (0.810) | 78/83/23 (0.649) | 0.00011 | 2.26 [1.49 to 3.41] | 0.34 |

| p.Ser2334Asn | rs9674961 | Ser | 71/30/2 (0.835) | 79/79/26 (0.644) | 0.0000062 | 2.71 [1.76 to 4.18] | 0.12 |

| p.Asp2554Glu | rs138516230 | Asp | 103/0/0 (1.00) | 174/9/1 (0.970) | 1.0 | NA | 1.0 |

| p.Cys3008Arg | rs61600413 | Cys | 101/2/0 (0.990) | 171/13/0 (0.964) | 0.081 | 3.83 [0.84 to 17.3] | 0.54 |

| p.Ala3468Val | rs142798005 | Ala | 101/2/0 (0.990) | 180/4/0 (0.989) | 0.90 | 1.12 [0.20 to 6.23] | 0.61 |

| p.Val3838Leu | rs35332090 | Val | 101/2/0 (0.990) | 153/29/2 (0.910) | 0.0020 | 9.71 [2.29 to 41.1] | 0.10 |

| p.Gly3915Glu | rs61740658 | Gly | 101/2/0 (0.990) | 157/25/2 (0.921) | 0.0043 | 8.21 [1.93 to 34.8] | 0.14 |

| p.Ala4399Thr | rs148731719 | Thr | 0/14/89 (0.067) | 1/20/159 (0.061) | 0.75 | 1.12 [0.55 to 2.25] | 0.063 |

Allele 1 and 2 represent at-risk allele and other allele, respectively; 11, homozygous genotype for allele 1; 12, heterozygous genotype; 22, homozygous genotype for allele 2. MMD indicates Moyamoya disease; NA, not applicable; RAF, risk allele frequency; SNPs, single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

Figure 2.

Disease-specific LD pattern within the RNF213 locus. Thirteen common SNPs (MAF >10%) and p.R4810K were selected from the present resequencing data. The pairwise LD of |D′| is displayed by the GOLD heat map.21 The gene structure was shown as an equal interval scale of SNPs in the LD map. LD indicates linkage disequilibrium; MAF, minor allele frequency; MMD, moyamoya disease; SNPs, single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

Analysis of Rare Variants in RNF213

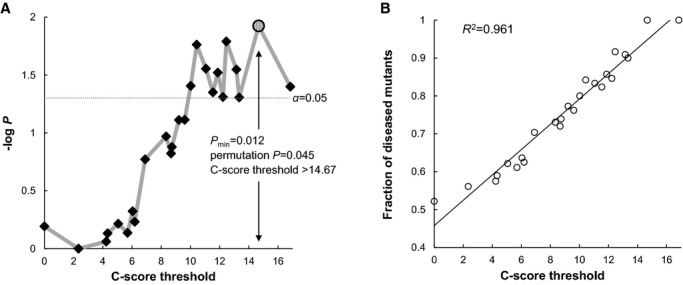

Among the previous Japanese studies shown in Figure 1, 2 MMD cohorts from Kamada et al7 and Miyatake et al9 were reported to be resequenced and contained rare coding variants in RNF213. They were included in subsequent analyses together with our 103 MMD patients, 190 TWMU and Kofu Neurosurgical Hospital controls, and 89 JPT subjects from the 1000 Genomes Project18 (Figure S1). As a result, a total of 30 rare missense variants with MAF <1% were identified in 370 combined Japanese MMD patients and 279 combined Japanese controls7,9,18 (Table 3). Nonsense, splice site, and frameshift variants were not identified. A simple burden test revealed no significant difference in mutant frequencies between the MMD patients and controls (P=0.76) because the observed rare variants may have included apparently nonassociated variants, which greatly reduced the statistical power (eg, p.T1866I appearing dominantly in the controls with low C-scores). To eliminate the influences of these potentially benign variants, we conducted a modified VT test using C-scores. The association signals increased along with C-score thresholds and reached significance (P=0.039) at the threshold >10.02 (Figure 3A). The empirical threshold for pathogenicity was 14.67, at which the most significant association was observed (Pmin=0.012). The evidence of the association was still significant after adjustments for multiple comparisons (permutation Pmin=0.045). In addition, fractions of diseased mutants were linearly correlated against the C-score thresholds (R2=0.961) and reached 100% at the proposed empirical threshold (Figure 3B). These results demonstrated that C-scores precisely prioritized the disease-associated variants on the RNF213 locus. Considering zygosity with p.R4810K, as described in the following section, ≈20% of the combined patients were estimated not to harbor the evidently associated rare variants (C-score >14.67) or p.R4810K.

Table 3.

Rare Missense Variants of RNF213 Among Japanese MMD Patients and Controls

| Nucleotide Change (AA Change) | dbSNP138 rs-ID | No. of Mutants | C-Score | Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMD (370) | Control (279) | ||||

| c.757C>T (p.Pro253Ser) | rs140369116 | 1 | 4 | 6.899 | 1, 2 |

| c.1052C>T (p.Ala351Val) | rs148593553 | 0 | 1 | 9.214 | 2 |

| c.2399C>T (p.Pro800Leu) | rs141005604 | 1 | 0 | 8.669 | 4 |

| c.3067C>T (p.Arg1023Trp) | — | 0 | 1 | 10.02 | 1 |

| c.5114C>A (p.Thr1705Lys) | rs147868237 | 1 | 0 | 13.15 | 4 |

| c.5597C>T (p.Thr1866Ile) | — | 1 | 4 | 2.339 | 1, 4 |

| c.5731C>A (p.Leu1911Ile) | — | 1 | 0 | 6.188 | 4 |

| c.6265C>T (p.Arg2089Trp) | — | 1 | 1 | 8.729 | 1, 4 |

| c.6979A>G (p.Asn2327Asp) | rs138044665 | 0 | 1 | 4.233 | 1 |

| c.7066C>T (p.Leu2356Phe) | rs200724769 | 1 | 0 | 5.694 | 4 |

| c.7250T>G (p.Ile2417Ser) | rs181965032 | 1 | 1 | 14.67 | 1, 4 |

| c.7319G>A (p.Gly2440Asp) | — | 0 | 1 | 4.33 | 1 |

| c.8111G>A (p.Arg2704Gln) | rs146486225 | 0 | 1 | 12.46 | 2 |

| c.9013G>A (p.Glu3005Lys) | rs147076172 | 0 | 2 | 5.056 | 1, 2 |

| c.9059A>T (p.Gln3020Leu) | — | 1 | 0 | 11.54 | 1 |

| c.9245A>G (p.Gln3082Arg) | — | 1 | 0 | 13.34 | 4 |

| c.9767C>T (p.Ser3256Leu) | — | 2 | 1* | 11.87 | 1, 4 |

| c.9923A>G (p.Asp3308Gly) | rs138979388 | 0 | 1 | 8.336 | 2 |

| c.9947C>T (p.Thr3316Ile) | — | 1 | 0 | 9.607 | 1 |

| c.11671A>G (p.Met3891Val) | — | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| c.12070T>A (p.Trp4024Arg) | — | 1 | 0 | 11.06 | 4 |

| c.12185G>A (p.Arg4062Gln) | — | 1 | 0 | 19.05 | 1 |

| c.12577G>C (p.Asp4193His) | rs143335048 | 0 | 1 | 10.43 | 2 |

| c.12748C>A (p.Pro4250Thr) | rs138029774 | 1 | 2 | 6.043 | 2, 4 |

| c.13699G>A (p.Val4567Met) | rs145282452 | 1 | 0 | 12.23 | 3 |

| c.13906G>A (p.Asp4636Asn) | — | 1 | 0 | 18.88 | 4 |

| c.14248G>A (p.Glu4750Lys) | — | 2 | 0 | 20.7 | 1, 4 |

| c.14293G>A (p.Val4765Met) | — | 1 | 0 | 18.43 | 3 |

| c.14749G>A (p.Glu4917Lys) | — | 1 | 0 | 17.35 | 4 |

| c.14780G>A (p.Arg4927Gln) | rs371045041 | 2 | 0 | 16.84 | 1, 4 |

| Total no. of mutants | 25 | 22 | |||

Figure 3.

Variable threshold test using combined annotation dependent depletion for rare missense variants in RNF213. A, −log10 P values for burden tests were plotted against C-score thresholds (diamonds). The empirical threshold was given if the P value was minimized (Pmin; shaded circle). Corrections for multiple comparisons were achieved by 1000 permutations on phenotypes. B, Fractions of diseased mutants per total mutants were plotted against C-score thresholds (open circles). The black line represents the least-squares regression line.

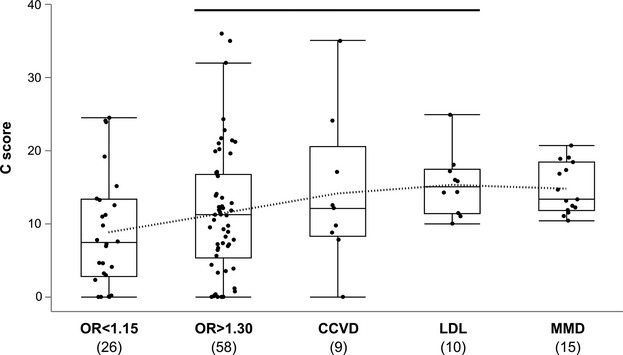

We next evaluated how these candidate variants may be associated with MMD in the context of mutational functions. Fifteen candidate variants were selected according to the VT test (P<0.05, C-score >10.02) (Table 3) and compared with various functional groups of missense variants (Figure S2). Although the candidate variants were clearly distinguished from the benign missense changes (P=1.4×10−7), their C-scores were significantly lower than those of the distinct pathogenic missense variants curated in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database (P<0.005). Their functional consequences were similar to those of the missense SNPs listed in the genomewide association study (GWAS) catalog.25 A total of 125 of these 327 missense GWAS hits were associated with complex binary traits (median OR 1.30, range 1.05 to 9.62). Reflecting phenotypic severity of MMD relative to common complex traits such as type 2 diabetes, the MMD variants had higher C-scores than missense GWAS hits with effect sizes in the bottom quartile (OR <1.15, P<0.05). There were no significant differences, however, in C-scores between the MMD variants and the other missense GWAS hits of common complex traits such as cardiocerebrovascular diseases and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (Figure 4). These lines of evidence support the previous epidemiological finding indicating a multifactorial etiology for MMD.5

Figure 4.

Boxplots of C-scores for missense SNPs in the GWAS catalog25 and 15 candidate variants for MMD. OR <1.15 represents binary trait loci with ORs in the bottom quartile; OR>1.3 indicates binary trait loci with ORs above median. The dotted line connects each average value. The black line over bars indicates no significant differences from the MMD candidate variants (Steel’s test). CCVD indicates cardiocerebrovascular disease loci; GWAS, genomewide association study; LDL, quantitative trait loci associated with serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level; MMD, moyamoya disease; OR, odds ratio; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

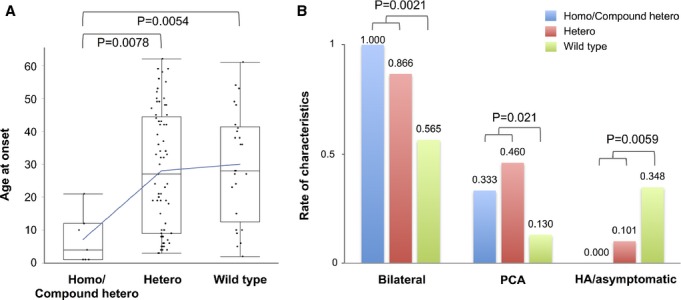

We identified 5 rare missense variants among our 103 MMD patients that were absent in the controls: p.T3316I and p.R4062Q as heterozygous, p.Q3020L and p.E4750K as compound heterozygous with p.R4810K, and p.R4927Q on the same haplotype with p.R4810K. These zygosities were confirmed by parental genotypes or haplotype phasing (Figures S3 and S4). Three of these variants—p.R4062Q, p.E4750K, and p.R4927Q—had higher C-scores than the proposed empirical threshold (>14.67) and were not present in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) browser version 0.3 (http://exac.broadinstitute.org). One variant, p.R4062Q, was shared between the proband and his paternal aunt with MMD and was also previously reported in a European patient,8 suggesting it could be a distinct susceptibility variant (Table S2). In contrast, 25 patients harbored no candidate variant in the coding region, which still included 4 familial cases. One of the 4 pedigrees harbored 3 affected members and is a good candidate for a future study searching for a novel susceptibility gene for MMD. Clinical characteristics according to the genotypes for the rare missense variants including p.R4810K demonstrated that age at onset was significantly lower in homozygous and compound heterozygous patients than in heterozygous or wild-type patients (P=7.8×10−3 or 5.4×10−3) (Figure 5A). In addition, the degrees of severity, such as the number of steno-occlusive posterior cerebral arteries, were significantly higher in mutant patients than in wild-type patients (P<0.05) (Figure 5B). These results further supported RNF213 variants increasing susceptibility to MMD.

Figure 5.

Clinical characteristics according to RNF213 genotypes. A, Box plots of age at onset. The blue line connects each average value. B, Differences in clinical characteristics reflecting the disease severity. Compound hetero indicates compound heterozygotes for p.R4810K and the other rare missense variants; HA, presenting headaches only; Homo, homozygotes for p.R4810K; PCA, posterior cerebral artery involvement.

Discussion

We provided evidence for the positive association of rare missense variants other than p.R4810K using the proposed VT test (permutation Pmin=0.045) (Figure 3). Further analyses indicated these variants may contribute to the development of MMD through a multifactorial etiology rather than as definite trait determinants (Figures S2 and 4). The C-score of the founder p.R4810K variant (6.746), for example, was markedly lower than that of pathogenic missense mutations in OMIM despite its extremely high OR (Figures1 and S2) because the arginine-to-lysine substitution remained unchanged as the same basic residues. The penetrance of this variant was also low: The prevalence of MMD (0.006%)2 was markedly lower than that of p.R4810K carriers (1.93%) (Figure 1) in the Japanese population. The newly identified pedigree harboring p.R4062Q (Table S2) and the recently reported European–American pedigree harboring p.D4013N (c.12037G>A, rs397514563)26 also showed incomplete penetrance. These lines of evidence suggest that the susceptibility variants of RNF213 require additional environmental or other genetic factors for the development of MMD. Mineharu et al postulated that the 5′ portion of RNF213 may have a modifier effect on the onset of MMD.27 They reported an MMD pedigree harboring 2 haplotypes, with both carrying p.R4810K. A difference in the 5′ end of the haplotypes caused by historical recombination was shown to affect penetrance in the pedigree. The haplotype structures including nearby regulatory regions need to be clarified for better understanding of the susceptibility of RNF213.

RNF213 encodes a 591-kDa protein harboring a RING (really interesting new gene) finger motif and AAA (ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities) domain, exhibiting E3 ubiquitin ligase activity and energy-dependent unfoldase activity, respectively. Although the physiological and biochemical functions of RNF213 remain largely unknown, its knockdown in zebrafish led to abnormal sprouting and intracranial vessels with an irregular diameter, suggesting a possible contribution to vascular formation8; however, in subsequent studies in mice, the knockout of Rnf213 did not lead to any visible cerebrovascular phenotypes.28,29 Although the reason for this discrepancy is not yet understood, these findings in knockout mice are consistent with our results showing that the deleterious effects of associated variants had significantly different profiles from those of loss-of-function missense mutations in OMIM (P=4.2×10−4) (Figure S2). Hitomi et al recently established induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from MMD patients and the controls of each genotype for p.R4810K.30 The findings demonstrated that angiogenic activity was significantly lower in vascular endothelial cells that differentiated from mutant iPS cells than in wild-type iPS cell–derived vascular endothelial cells. The gene expression profiles of iPS cell–derived vascular endothelial cells further revealed the downregulation of cell cycle–related genes in the mutants, which induced mitotic abnormalities associated with this endothelial dysfunction.30,31 Further studies are warranted to elucidate how p.R4810K downregulates these cell cycle–related genes and whether the other associated variants replicate the same condition.

Genetic testing of RNF213 is now drawing attention in Japan. Miyawaki et al reported that 23.8% of Japanese patients with intracranial major artery stenosis/occlusion who did not meet the diagnostic criteria of MMD also carried p.R4810K; a particular subgroup of patients with intracranial major artery stenosis/occlusion, conventionally regarded as another complex trait, shared the same genetic risk factor common to MMD in the Japanese population.32,33 Taking into consideration the present results, resequencing of RNF213 may become increasingly important for assessing genetic risks in patients with steno-occlusive lesions around the circle of Willis; however, RNF213 is a large gene that encodes 5207 amino acids and thus harbors a number of missense variants in the general population to the same degree as in patients (Table 3). The false assignment of pathogenicity may lead to incorrect prognostic, therapeutic, or reproductive assessments of patients.10 The present VT analysis may provide a tentative criterion for the reasonable pathogenic assignment of RNF213 variants; however, caution should be exercised in their interpretation.

In conclusion, we confirmed that not only p.R4810K but also other putatively functional variants of RNF213 conferred susceptibility to MMD in Japanese patients. Our analysis also revealed the multifactorial etiology of this disease, and ≈20% of Japanese MMD patients did not harbor significant susceptibility variants of RNF213, among which still included familial cases. This result indicates that other susceptibility genes exist, providing further insight into the pathogenesis and future therapeutic targets of MMD.

Source of Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (No. 23592109) to Onda, and by a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (No. 26670649) to Akagawa from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting Information

Data S1.Supplemental methods.

Figure S1. Flowchart describing the present study. A, The samples used for variant detection of RNF213. B, Depending on the genotypic frequencies in the patients, analytical samples were increased in stages. Red letters indicate the present DNA samples in hand. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; SNV, single-nucleotide variant.

Figure S2. Violin plots of C-scores across various functional categories of missense changes. Benign represents ancestral chimpanzee alleles altered in the human lineage; GWAS, listed in the GWAS catalogue [6]; Loss-of-function and Gain-of-function, curated in the OMIM database. Steel-Dwass test *P<0.05, **P<0.005 and ***P<0.0005, significantly different from the MMD candidate variants. GWAS indicates genomewide association study; MMD, moyamoya disease; OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man.

Figure S3. Chromatograms of 5 rare missense variants among our 103 MMD patients that ware absent in the controls. MMD indicates moyamoya disease.

Figure S4. Haplotype phasing for patients harboring multiple rare variants. A, Direct haplotype phasing for patients harboring p.R4810K and p.R4927Q. B, In patients harboring p.Q3020L and p.R4810K, interval phase inference using tight LD was combined with direct phasing. LD indicates linkage disequilibrium.

Table S1. Primer sequences for exon resequencing of RNF213.

Table S2. Clinical features of subjects harboring rare missense variants other than p.R4810K.

References

- Suzuki J, Takaku A. Cerebrovascular, “moyamoya” disease. Disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:288–299. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480090076012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houkin K, Kuroda S, Nakayama N. Cerebral revascularization for moyamoya disease in children. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2001;12:575–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Yoshimoto T, Hashimoto N, Okada Y, Tsuji I, Tominaga T, Nakagawara J, Takahashi JC JAM Trial Investigators. Effects of extracranial-intracranial bypass for patients with hemorrhagic moyamoya disease: results of the Japan Adult Moyamoya Trial. Stroke. 2014;45:1415–1421. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama S, Kusaka Y, Fujimura M, Wakai K, Tamakoshi A, Hashimoto S, Tsuji I, Inaba Y, Yoshimoto T. Prevalence and clinicoepidemiological features of moyamoya disease in Japan: findings from a nationwide epidemiological survey. Stroke. 2008;39:42–47. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama Y, Kanai N, Osawa M. Clinical genetic analysis on the moyamoya disease. In: Yonekawa Y, editor. The Research Committee on Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis (Moyamoya Disease) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare Japan: Annual Report 1992. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health and Welfare Japan; 1992. pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Yonekawa Y, Ogata N, Kaku Y, Taub E, Imhof HG. Moyamoya disease in Europe, past and present status. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99:S58–S60. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(97)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada F, Aoki Y, Narisawa A, Abe Y, Komatsuzaki S, Kikuchi A, Kanno J, Niihori T, Ono M, Ishii N, Owada Y, Fujimura M, Mashimo Y, Suzuki Y, Hata A, Tsuchiya S, Tominaga T, Matsubara Y, Kure S. A genome-wide association study identifies RNF213 as the first Moyamoya disease gene. J Hum Genet. 2010;56:34–40. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Morito D, Takashima S, Mineharu Y, Kobayashi H, Hitomi T, Hashikata H, Matsuura N, Yamazaki S, Toyoda A, Kikuta K, Takagi Y, Harada KH, Fujiyama A, Herzig R, Krischek B, Zou L, Kim JE, Kitakaze M, Miyamoto S, Nagata K, Hashimoto N, Koizumi A. Identification of RNF213 as a susceptibility gene for moyamoya disease and its possible role in vascular development. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyatake S, Miyake N, Touho H, Nishimura-Tadaki A, Kondo Y, Okada I, Tsurusaki Y, Doi H, Sakai H, Saitsu H, Shimojima K, Yamamoto T, Higurashi M, Kawahara N, Kawauchi H, Nagasaka K, Okamoto N, Mori T, Koyano S, Kuroiwa Y, Taguri M, Morita S, Matsubara Y, Kure S, Matsumoto N. Homozygous c.14576G>A variant of RNF213 predicts early-onset and severe form of moyamoya disease. Neurology. 2012;78:803–810. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318249f71f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur DG, Manolio TA, Dimmock DP, Rehm HL, Shendure J, Abecasis GR, Adams DR, Altman RB, Antonarakis SE, Ashley EA, Barrett JC, Biesecker LG, Conrad DF, Cooper GM, Cox NJ, Daly MJ, Gerstein MB, Goldstein DB, Hirschhorn JN, Leal SM, Pennacchio LA, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Sunyaev SR, Valle D, Voight BF, Winckler W, Gunter C. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature. 2014;508:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature13127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihab HA, Gough J, Cooper DN, Stenson PD, Barker GL, Edwards KJ, Day IN, Gaunt TR. Predicting the functional, molecular, and phenotypic consequences of amino acid substitutions using hidden Markov models. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:57–65. doi: 10.1002/humu.22225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet. 2014;46:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Kryukov GV, de Bakker PI, Purcell SM, Staples J, Wei LJ, Sunyaev SR. Pooled association tests for rare variants in exon-resequencing studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:832–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GT, Peng B, Leal SM. Variant association tools for quality control and analysis of large-scale sequence and genotyping array data. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:770–783. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui M. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis (‘moyamoya’ disease). Research Committee on Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis (Moyamoya Disease) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99:S238–S240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineharu Y, Liu W, Inoue K, Matsuura N, Inoue S, Takenaka K, Ikeda H, Houkin K, Takagi Y, Kikuta K, Nozaki K, Hashimoto N, Koizumi A. Autosomal dominant moyamoya disease maps to chromosome 17q25.3. Neurology. 2008;70:2357–2363. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000291012.49986.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigginton JE, Cutler DJ, Abecasis GR. A note on exact tests of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:887–893. doi: 10.1086/429864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill WG, Robertson A. Linkage disequilibrium in finite populations. Theor Appl Genet. 1968;38:226–231. doi: 10.1007/BF01245622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abecasis GR, Cookson WO. GOLD—graphical overview of linkage disequilibrium. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:182–183. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning SR, Browning BL. Rapid and accurate haplotype phasing and missing data inference for whole genome association studies using localized haplotype clustering. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1084–1097. doi: 10.1086/521987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Jian X, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP: a lightweight database of human non-synonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:894–899. doi: 10.1002/humu.21517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Jian X, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP v2.0: a database of human non-synonymous SNVs and their functional predictions and annotations. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:E2393–E2402. doi: 10.1002/humu.22376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welter D, MacArthur J, Morales J, Burdett T, Hall P, Junkins H, Klemm A, Flicek P, Manolio T, Hindorff L, Parkinson H. The NHGRI GWAS catalog, a curated resource of SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D1001–D1006. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi AC, Guo D, Ren Z, Flynn K, Santos-Cortez RL, Leal SM, Wang GT, Regalado ES, Steinberg GK, Shendure J, Bamshad MJ University of Washington Center for Mendelian Genomics. Grotta JC, Nickerson DA, Pannu H, Milewicz DM. RNF213 rare variants in an ethnically diverse population with Moyamoya disease. Stroke. 2014;45:3200–3207. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineharu Y, Takagi Y, Takahashi JC, Hashikata H, Liu W, Hitomi T, Kobayashi H, Koizumi A, Miyamoto S. Rapid progression of unilateral moyamoya disease in a patient with a family history and an RNF213 risk variant. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36:155–157. doi: 10.1159/000352065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Yamazaki S, Takashima S, Liu W, Okuda H, Yan J, Fujii Y, Hitomi T, Harada KH, Habu T, Koizumi A. Ablation of Rnf213 retards progression of diabetes in the Akita mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;432:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonobe S, Fujimura M, Niizuma K, Nishijima Y, Ito A, Shimizu H, Kikuchi A, Arai-Ichinoi N, Kure S, Tominaga T. Temporal profile of the vascular anatomy evaluated by 9.4-T magnetic resonance angiography and histopathological analysis in mice lacking RNF213: a susceptibility gene for moyamoya disease. Brain Res. 2014;1552:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi T, Habu T, Kobayashi H, Okuda H, Harada KH, Osafune K, Taura D, Sone M, Asaka I, Ameku T, Watanabe A, Kasahara T, Sudo T, Shiota F, Hashikata H, Takagi Y, Morito D, Miyamoto S, Nakao K, Koizumi A. Downregulation of Securin by the variant RNF213 R4810K (rs112735431, G>A) reduces angiogenic activity of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived vascular endothelial cells from moyamoya patients. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;438:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi T, Habu T, Kobayashi H, Okuda H, Harada KH, Osafune K, Taura D, Sone M, Asaka I, Ameku T, Watanabe A, Kasahara T, Sudo T, Shiota F, Hashikata H, Takagi Y, Morito D, Miyamoto S, Nakao K, Koizumi A. The moyamoya disease susceptibility variant RNF213 R4810K (rs112735431) induces genomic instability by mitotic abnormality. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;439:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki S, Imai H, Takayanagi S, Mukasa A, Nakatomi H, Saito N. Identification of a genetic variant common to moyamoya disease and intracranial major artery stenosis/occlusion. Stroke. 2012;43:3371–3374. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.663864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki S, Imai H, Shimizu M, Yagi S, Ono H, Mukasa A, Nakatomi H, Shimizu T, Saito N. Genetic variant RNF213 c.14576G>A in various phenotypes of intracranial major artery stenosis/occlusion. Stroke. 2013;44:2894–2897. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.Supplemental methods.

Figure S1. Flowchart describing the present study. A, The samples used for variant detection of RNF213. B, Depending on the genotypic frequencies in the patients, analytical samples were increased in stages. Red letters indicate the present DNA samples in hand. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; SNV, single-nucleotide variant.

Figure S2. Violin plots of C-scores across various functional categories of missense changes. Benign represents ancestral chimpanzee alleles altered in the human lineage; GWAS, listed in the GWAS catalogue [6]; Loss-of-function and Gain-of-function, curated in the OMIM database. Steel-Dwass test *P<0.05, **P<0.005 and ***P<0.0005, significantly different from the MMD candidate variants. GWAS indicates genomewide association study; MMD, moyamoya disease; OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man.

Figure S3. Chromatograms of 5 rare missense variants among our 103 MMD patients that ware absent in the controls. MMD indicates moyamoya disease.

Figure S4. Haplotype phasing for patients harboring multiple rare variants. A, Direct haplotype phasing for patients harboring p.R4810K and p.R4927Q. B, In patients harboring p.Q3020L and p.R4810K, interval phase inference using tight LD was combined with direct phasing. LD indicates linkage disequilibrium.

Table S1. Primer sequences for exon resequencing of RNF213.

Table S2. Clinical features of subjects harboring rare missense variants other than p.R4810K.