Abstract

Background

The genus Herbidospora comprises actinomycetes belonging to the family Streptosporangiaceae and currently contains five recognized species. Although other genera of this family often produce bioactive secondary metabolites, Herbidospora strains have not yet been reported to produce secondary metabolites. In the present study, to assess their potential as secondary metabolite producers, we sequenced the whole genomes of the five type strains and searched for the presence of their non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) and type-I polyketide synthase (PKS) gene clusters. These clusters are involved in the major secondary metabolite–synthetic pathways in actinomycetes.

Results

The genome sizes of Herbidospora cretacea NBRC 15474T, Herbidospora mongoliensis NBRC 105882T, Herbidospora yilanensis NBRC 106371T, Herbidospora daliensis NBRC 106372T and Herbidospora sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T were 8.3, 9.0, 7.9, 8.5 and 8.6 Mb, respectively. They contained 15–18 modular NRPS and PKS gene clusters. Thirty-two NRPS and PKS pathways were identified, among which 9 pathways were conserved in all 5 strains, 8 were shared in 2–4 strains, and the remaining 15 were strain-specific. We predicted the chemical backbone structures of non-ribosomal peptides and polyketides synthesized by these gene clusters, based on module number and domain organization of NRPSs and PKSs. The relationship between 16S rRNA gene sequence-based phylogeny of the five strains and the distribution of their NRPS and PKS gene clusters were also discussed.

Conclusions

The genomes of Herbidospora strains carry as many NRPS and PKS gene clusters, whose products are yet to be isolated, as those of Streptomyces. Herbidospora members should synthesize large and diverse metabolites, many of whose chemical structures are yet to be reported. In addition to those conserved within this genus, each strain possesses many strain-specific gene clusters, suggesting the diversity of these pathways. This diversity could be accounted for by genus-level vertical inheritance and recent acquisition of these gene clusters during evolution. This genome analysis suggested that Herbidospora strains are an untapped and attractive source of novel secondary metabolites.

Keywords: Herbidospora cretacea, Herbidospora mongoliensis, Herbidospora yilanensis, Herbidospora daliensis, Herbidospora sakaeratensis, Genome sequence, Type-I polyketide synthase, Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase

Background

Actinomycetes are rich sources for bioactive secondary metabolites. In particular, members of the genus Streptomyces have attracted attention as the most useful screening sources for new drug leads. Since the discovery of streptomycin from Streptomyces griseus, a large number of antibiotics have been identified from cultures of this genus [1, 2]. Consequently, the chance of finding novel secondary metabolites from Streptomyces members has recently dwindled. Thus, the focus of screening has moved to less exploited genera of rare actinomycetes. For example, members of the family Streptosporangiaceae are reported to be a promising source, and many novel compounds have been isolated from genera such as Streptosporangium in this family [3].

The genus Herbidospora was established as a new genus of the family Streptosporangiaceae in 1993 and currently contains five species: Herbidospora cretacea, Herbidospora yilanensis, Herbidospora daliensis,Herbidospora sakaeratensis and Herbidospora mongoliensis [4–7]. Although this genus belongs to the family Streptosporangiaceae, no secondary metabolites have been reported from Herbidospora strains in over 20 years, which motivated us to assess the potential of Herbidospora members as secondary metabolite producers.

Recent genome projects of actinomycetes revealed that each actinomycete genome encodes various biosynthetic pathways, and half to three quarters are associated with non-ribosomal peptide synthase (NRPS) and polyketide synthase (PKS) pathways [8]. This suggested that non-ribosomal peptide and polyketide compounds are the major secondary metabolites of actinomycetes [8]. Non-ribosomal peptides, polyketides and their hybrid compounds often show pharmaceutically useful bioactivities, many of which have been developed into various drugs, such as antibiotics, anticancer agents and immunosuppressants. Therefore, NRPS and PKS genes in actinomycete strains are often assessed to screen potential secondary metabolite producers [9, 10].

Genes for each non-ribosomal peptide and/or polyketide synthesis are generally organized into a gene cluster, in which NRPS and PKS genes play main roles to synthesize non-ribosomal peptides and polyketide chains, respectively. NRPSs and type-I PKSs are mega-synthases, containing multiple catalytic domains organized into modules, where each module carries out a cycle of chain elongation. Typically, each module contains at least three domains: a condensation (C) domain, an adenylation (A) domain and a thiolation (T) domain in NRPS modules; and a ketosynthase (KS) domain, an acyltransferase (AT) domain and an acyl carrier protein (ACP) in type-I PKS modules. Optional domains may also be present in each module to chemically modify elongating chains. The products are synthesized from simple building blocks such as acyl-CoA and amino-acid units based on an accepted theory called the assembly line rule [11]; therefore, the chemical structures of synthesized peptides and/or polyketide backbones can be predicted from domain organizations of the NRPS and/or PKS gene clusters, respectively.

In this study, we sequenced the whole genomes of all type strains of the genus Herbidospora because no Herbidospora genome sequence was registered in public databases when we began this study. We then examined the NRPS and type-I PKS gene clusters in the genome sequences and predicted the chemical backbone structures of these metabolites to assess the potential of the genus as secondary metabolite producers, and to provide information on the novelty and diversity of NRPS and PKS pathways. We also discussed how diversity was acquired during the evolution of Herbidospora species, based on the relationship between the distribution of these pathways and the taxonomic position of each strain.

Methods

Whole-genome sequencing

Genomic DNAs of H. cretacea NBRC 15474T, H. mongoliensis NBRC 105882T, H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T, H. daliensis NBRC 106372T and H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T were prepared from liquid-dried cells in ampoules provided from the NBRC culture collection, using a Qiagen EZ1 tissue kit and an EZ1 advanced instrument (Qiagen), and sequenced using paired-end sequencing with MiSeq (Illumina). The sequence redundancy for the five draft genomes ranged from 61.7 to 70.6. The sequence reads were assembled using Newbler version 2.6 software and subsequently assessed using GenoFinisher software [12].

Analysis of NRPS and type-I PKS gene clusters

Coding sequences in the draft genome sequences were predicted using Prodigal version 2.6 [13]. NRPS and type-I PKS gene clusters were determined as previously reported [9, 10]. PKS and NRPS genes having only a single domain were excluded from the present analysis, because we considered them atypical; we focused on multi-domain genes.

Searches for orthologous gene clusters among strains

A BLASTP search was performed using the NCBI Protein BLAST program against the non-redundant protein sequence database. We considered genes of distinct strains to be orthologous when their closest homologs in the BLASTP search were the same, and also when their domain organizations were identical or almost the same.

Prediction of metabolites derived from NRPS and/or type-I PKS gene clusters

We used antiSMASH [14], a website for antibiotics and secondary metabolite analysis, to predict substrates for A domains and AT domains. Based on the substrates and the assembly line rule [11], we predicted the amino acid combinations of peptide chains and chemical structures of polyketide chains synthesized by NRPS and type-I PKS gene clusters, respectively.

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences

16S rRNA gene sequences were downloaded from ‘Sequence Information’ of the NBRC Culture Catalogue [15], and aligned using ClustalX2 [16]. A phylogenetic tree was reconstructed by the neighbor-joining method [17]. The resultant tree topologies were evaluated by bootstrap analysis [18]. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of Acrocarpospora corrugata NBRC 13972T was used as the outgroup.

Results and discussion

We sequenced the whole genomes of all the type strains in the genus Herbidospora. The genome sizes ranged from 7.9 to 9.0 Mb, showing medium size compared with those of Streptomyces strains (5.0–11.9 Mb) and of strains in the family Streptosporangiaceae (5.5–13 Mb). The five strains each possessed 15–18 gene clusters for NRPS, PKS/NRPS hybrid and type-I PKS pathways, which were similar to the numbers found in Streptomyces [8, 10, 19–22]. The numbers of the three types of gene clusters in each strain are listed in Table 1. Table 2 shows details of all the clusters found in each genome. Orthologous genes and gene clusters are aligned in the same row of the table. These orthologous genes showed the same domain organization; therefore, their gene clusters should synthesize the same products, as shown in the ‘Presumable product’ column of Table 2. Among the 32 gene clusters (nrps-1 to -16, pks/nrps-1 to -4, pks-1 to -12) identified from the 5 strains, 9 were conserved in all strains, 8 were shared in 2–4 strains, and 15 were strain-specific. During this study, the draft genome sequence of H. cretacea NRRL B-16917 was published in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases (accession no., JODQ00000000.1). However, it is questionable whether strain NRRL B-16917 is H. cretacea, because its 16S rRNA gene showed higher sequence similarity to those of type strains of H. yilanensis (99.1 %), H. sakaeratensis (98.8 %), H. daliensis (98.3 %) than to the type strain of H. cretacea (98.0 %), and its phylogenetic position was not close to the type strain of H. cretacea in the phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences (data not shown). The scientific name of strain NRRL B-16917 is unclear; therefore, we did not analyze its NRPS and PKS gene clusters and focused on those of the five type strains in the present study.

Table 1.

Genome sequencing and numbers of modular non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) and type-I polyketide synthase (PKS) gene clusters in Herbidospora strains

| Strain | Reads (Mb) | No. of scaffolds | Genome size (bp) | G + C content (%) | Accession no. | Number of gene clusters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRPS | PKS/NRPS hybrid | PKS | Total | ||||||

| H. cretacea NBRC 15474T | 582.1 | 36 | 82,82,092 | 70.7 | BBXG01000000 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 15 |

| H. mongoliensis NBRC 105882T | 556.2 | 47 | 90,71,776 | 69.4 | BBXD01000000 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 17 |

| H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T | 546.7 | 67 | 78,57,004 | 70.7 | BBXE01000000 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 15 |

| H. daliensis NBRC 106372T | 586.2 | 18 | 85,23,669 | 70.8 | BBXF01000000 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 15 |

| H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T | 590.3 | 35 | 83,49,170 | 70.9 | BBXC01000000 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 18 |

Table 2.

Open reading frames encoding multidomain NRPSs and PKSs in modular NRPS and PKS gene clusters of Herbidospora strains

| Gene cluster | Scaffold-orf no. (size, % identity/similarity to closest homolog) | Domain organization | Presumed product | Closest homolog | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. cretacea NBRC 15474T | H. mongoliensis NBRC 105882T | H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T | H. daliensis NBRC 106372T | H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T | Accession no. | Origin | |||

| nrps-1 | s01-orf204 (6699aa, 88/92) | s02-orf3 (6749aa, 85/90) | s34-orf56 (6711aa, 92/94) | s03-orf732 (6697aa, 89/93) | s01-orf733 (6657aa, 91/94) | A/MT/T-C/Aser/T-C/Aorn/MT/T-C/A/T-C/Aser/T-C/A/T/E | x-Ser-mOrn-x-Ser-x (albachelin-like siderophore) | WP_034384656 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| nrps-2 | s17-orf53* (1026aa, 91/93) | s03-orf338* (988aa, 89/92) | s13-orf130* (1010aa, 93/94) | s05-orf276* (1051aa, 91/94) | s15-orf51* (974aa, 91/94) | A/T-C | x-Gly-Lys-x | WP_030456013 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| s17-orf54 (973aa, 88/92) | s03-orf339 (990aa, 86/91) | s13-orf129 (1015aa, 90/92) | s05-orf275 (974aa, 90/93) | s15-orf52 (975aa, 91/94) | C/Agly/T | WP_030456012 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| s17-orf55 (979aa, 88/90) | s03-orf340 (991aa, 85/89) | s13-orf128 (972aa, 90/92) | s05-orf274 (961aa, 91/93) | s15-orf53 (961aa, 91/93) | C/A(lys)/T | WP_034385955 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| s17-orf58 (1351aa, 88/92) | s03-orf343 (1341aa, 89/93) | s13-orf125 (1348aa, 94/96) | s05-orf271 (1343aa, 92/95) | s15-orf56 (1350aa, 92/95) | C/A/T-TE | WP_030456008 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| nrps-3 | s08-orf344 (2105aa, 86/90) | s17-orf93 (2104aa, 85/90) | s12-orf143 (2199aa, 90/91) | s01-orf374 (2125aa, 89/92) | s17-orf87 (2150aa, 90/92) | Agly/T-C/T-C/Agly/T | Gly-?-Gly-Asp | WP_034384991 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| s08-orf343 (1775aa, 91/95) | s17-orf92 (1766aa, 86/92) | s12-orf144 (1766aa, 95/97) | s01-orf373 (1776aa, 92/96) | s17-orf86 (1777aa, 92/95) | C/Aasp/T-TE | WP_030453964 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| nrps-4 | s01-orf4* (1934aa, 88/91) | s02-orf218* (1932aa, 88/93) | s08-orf109* (1933aa, 95/97) | s03-orf522* (1932aa, 93/95) | s01-orf545* (1932aa, 94/95) | C/A/T-C/Alys/T | x-Lys-Asp | WP_030453192 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| s01-orf5 (1721aa, 93/96) | s02-orf217 (1722aa, 90/94) | s08-orf108 (1721aa, 96/98) | s03-orf523 (1721aa, 94/96) | s01-orf546 (1721aa, 95/96) | C/Aasp/T-TE | WP_030453193 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| nrps-5 | s03-orf142 (1742aa, 87/91) | s04-orf515 (1751aa, 86/91) | s21-orf82 (1738aa, 95/97) | s01-orf929 (1731aa, 91/93) | s02-orf479 (1729aa, 91/94) | C/Aasp/T-TE | Gly-Asp | WP_030454483 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| s03-orf139 (1011aa, 93/95) | s04-orf518 (1011aa, 93/95) | s21-orf85 (1011aa, 96/97) | s01-orf932 (1011aa, 93/96) | s02-orf482 (1011aa, 94/96) | C/Agly/T | WP_034384898 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| nrps-6 | s06-orf42* (474aa, 87/91) | s05-orf174* (470aa, 86/90) | s06-orf123* (471aa, 92/94) | s14-orf189* (471aa, 92/93) | s12-orf45* (471aa, 92/94) | C/T | ?-Asn | WP_030450820 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| s06-orf40 (1678aa, 57/68) | s05-orf172 (1716aa, 55/66) | s06-orf125 (1684aa, 57/68) | s14-orf187 (1677aa, 57/67) | s12-orf47 (1677aa, 57/67) | C/Aasn/T-TE | WP_031172905 | Streptosporangium roseum NRRL B-2638 | ||

| nrps-7 | s05-orf29 (1709aa, 91/94) | s02-orf251 (1777aa, 90/94) | s08-orf140 (1776aa, 96/97) | s03-orf492 (1789aa, 94/96) | s01-orf513 (1812aa, 94/95) | C/Aasn/T-TE | (Asn) | WP_030453154 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| nrps-8 | – | – | s05-orf295 (1018aa, 92/94) | s03-orf778 (1021aa, 89/92) | s01-orf772 (1019aa, 89/91) | A/T-TE | x–x | WP_030453437 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| s05-orf293 (1097aa, 95/97) | s03-orf780 (1097aa, 93/96) | s01-orf774 (1097aa, 94/96) | C/A/T | WP_030453439 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||||

| nrps-9 | – | – | s02-orf346 (3681aa, 56/63) | – | s02-orf28 (3673aa, 53/63) | Agly/T-C/Aasn/T-C/A/T-C/A(lys)/T | Gly-Asn-x-Lys-Thr-x | WP_026126874 | Nocardiopsis xinjiangensis YIM 90004 |

| s02-orf347 (2407aa, 59/70) | s02-orf27 (2385aa, 59/70) | C/Athr/T-C/A/T-TE | WP_040918882 | Saccharomonospora glauca K62 | |||||

| nrps-10 | s05-orf197* (1110aa, 58/67) | s02-orf401* (1110aa, 58/68) | – | – | – | T-C/Aser/T | x-Ser-?-x–x-Ser | WP_037800301 | Streptomyces sp. Mg1 |

| s05-orf195* (1679aa, 37/48) | s02-orf399* (1679aa, 37/48) | C/T-C/A/T | AGC43421 | Myxococcus stipitatus DSM 14675 | |||||

| s05-orf184 (540aa, 39/52) | s02-orf388 (527aa, 38/50) | A/T | WP_017558240 | Nocardiopsis baichengensis YIM 90130 | |||||

| s05-orf182 (1693aa, 48/57) | s02-orf386 (1700aa, 46/57) | C/T-C/Aser/T-TE | ACU38342 | Actinosynnema mirum DSM 43827 | |||||

| nrps-11 | s08-orf166 (1237aa, 63/71) | s13-orf80 (1230aa, 65/73) | – | – | – | C/A/T-TE | x | ACU75141 | Catenulispora acidiphila DSM 44928 |

| nrps - 12 | – | – | – | s01-orf155 (3126aa, 96/97) | – | C/Aphe/T-C/Aasp/T-C/Aasp/T | Phe-Asp-Asp-x-Asp-Ser-x–x-Phe-x-Val-x-Tyr-Asp-Asn-Tyr-x-Tyr-Asp–Asp-x-Asp | WP_034385663 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| s01-orf140 (11331aa, 55/65) | – | C/A/T-C/Aasp/T-C/Aser/T-C/A/T-C/A/T-C/Aphe/T-C/A/T-C/Aval/T-C/A/T-C/Atyr/T-C/Aasp/T | EIF87998 | Streptomyces tsukubensis NRRL 18488 | |||||

| s01-orf139 (8503aa, 54/64) | – | C/Aasn/T-C/Atyr/T-C/A/T-C/Atyr/T-C/Aasp/T-C/Aasp/T-C/A/T-C/Aasp/T-TE | EIF87998 | Streptomyces tsukubensis NRRL 18488 | |||||

| nrps - 13 | – | – | – | s02-orf353 (1637aa, 51/59) | – | C/Agly-C/Aala/T | Gly-Ala | WP_026213748 | Nonomuraea coxensis DSM 45129 |

| nrps - 14 | – | – | – | – | s01-orf286 (2965aa, 39/50) | C/A/T-C/A/T-C/Aser/T | Val-x-x-Ser-Asn–Asn | ERK92233 | Myxococcus sp. (contaminant ex DSM 436) |

| s01-orf285 (2462aa, 56/67) | C/Aasn/T-C/Aasn/T-C | WP_039739900 | Saccharomonospora halophila 8 | ||||||

| s01-orf277* (620aa, 52/63) | Aval/T | WP_033666206 | Salinispora pacifica CNS055 | ||||||

| nrps - 15 | – | – | – | – | s13-orf204 (1086aa, 58/66) | Agly/C/T | ?-Gly | ETK35217 | Microbispora sp. ATCC PTA-5024 |

| nrps - 16 | – | – | – | – | s14-orf131 (1233aa, 66/75) | C/A/T | x | ELS56639 | Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tue57 |

| pks/nrps-1 | s04-orf226 (3534aa, 82/87) | s07-orf8 (3458aa, 82/87) | s05-orf58 (3534aa, 90/92) | s06-orf132 (3570aa, 84/88) | s01-orf1038 (3515aa, 86/89) | CoL/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-C/A/T-C | ?-pk-x | WP_034384725 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| pks/nrps - 2 | – | s11-orf48 (1776aa, 52/66) | – | – | – | KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | pk-x-x–x-Val-x-x-Ser-Thr-Asn-Asn–Asn-Thr-Asn | EPH45771 | Streptomyces aurantiacus JA 4570 |

| s11-orf45 (1637aa, 50/59) | A/T-C/A/T | EPH45774 | Streptomyces aurantiacus JA 4570 | ||||||

| s11-orf44 (1073aa, 71/76) | C/A/T | CAC01623 | Planobispora rosea ATCC 53733 | ||||||

| s11-orf43 (2007aa, 50/60) | C/Aval/T-C/A/T | EPH43046 | Streptomyces aurantiacus JA 4570 | ||||||

| s11-orf41 (2145aa, 47/57) | C/A/T-C/Aser/T | EPH43048 | Streptomyces aurantiacus JA 4570 | ||||||

| s11-orf40 (3193aa, 41/54) | C/Athr/T-C/Aasn/T-C/Aasn/T | WP_018350842 | Longispora albida DSM 44784 | ||||||

| s11-orf39 (1064aa, 45/58) | C/Aasn/T | WP_030327232 | Streptomyces sp. NRRL B-3229 | ||||||

| s11-orf38 (2516aa, 44/55) | C/Athr/T-C/Aasn/T-TE | EPH43049 | Streptomyces aurantiacus JA 4570 | ||||||

| pks/nrps - 3 | – | – | s05-orf134 (1316aa, 44/56) | – | – | KS/AT/ACP-TE | Leu-Val-Leu-Ser-pk | EWC62839 | Actinokineospora sp. EG49 |

| s05-orf130 (1006aa, 42/59) | Aleu/T/E | BAH43926 | Brevibacillus brevis NBRC 100599 | ||||||

| s05-orf129 (3118aa, 46/60) | C/Aval/T-C/Aleu/T-C/Aser/T | AGC43421 | Myxococcus stipitatus DSM 14675 | ||||||

| pks/nrps - 4 | – | – | – | – | s08-orf1 (> 346aa, 55/61) | …ACP | See Fig. 1h | WP_037075741 | Pseudonocardia spinosispora DSM 44797 |

| s08-orf2 (6590aa, 72/79) | KS/ATm/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH | WP_042407435 | Streptacidiphilus carbonis NBRC 100919 | ||||||

| s08-orf2_1 (379aa, 83/88) | KR/ACP | WP_042407435 | Streptacidiphilus carbonis NBRC 100919 | ||||||

| s08-orf3 (4716aa, 57/67) | KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-TE | WP_037075679 | Pseudonocardia spinosispora DSM 44797 | ||||||

| s08-orf8 (7045aa, 69/77) | KS/ATm/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP | WP_037075740 | Pseudonocardia spinosispora DSM 44797 | ||||||

| s08-orf9 (5636aa, 51/62) | KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | ADL46003 | Micromonospora aurantiaca ATCC 27029 | ||||||

| s08-orf10* (997aa, 65/76) | A/T | WP_042397191 | Streptacidiphilus carbonis NBRC 100919 | ||||||

| pks-1 | s14-orf123 (2788aa, 90/92) | s10-orf265 (2815aa, 89/92) | s18-orf5 (2796aa, 90/92) | s03-orf254 (2800aa, 89/91) | s01-orf250 (2782aa, 91/94) | KS/ATm/ACP-KS/ATm/DH/KR/ACP | See Fig. 1a | WP_034382778 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| s14-orf124 (1807aa, 93/95) | s10-orf264 (1806aa, 93/96) | s18-orf6 (1800aa, 94/96) | s03-orf255 (1794aa, 94/96) | s01-orf251 (1793aa, 94/95) | KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | WP_030450097 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| s14-orf125 (1800aa, 91/93) | s10-orf263 (1801aa, 92/93) | s18-orf7 (1795aa, 92/94) | s03-orf256 (1795aa, 90/93) | s01-orf252 (1798aa, 92/93) | KS/ATm/DH/KR/ACP | WP_030450096 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| s14-orf126 (1567aa, 91/94) | s10-orf262 (1578aa, 92/94) | s18-orf8 (1573aa, 91/94) | s03-orf257 (1567aa, 91/94) | s01-orf253 (1595aa, 90/92) | KS/AT/KR/ACP | WP_030450095 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| s14-orf127 (3057aa, 92/)94 | s10-orf261 (3070aa, 91/94) | s18-orf9 (3062aa, 92/94) | s03-orf258 (3031aa, 92/94) | s01-orf254 (3033aa, 92/94) | KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | WP_030450094 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| s14-orf135* (1265aa, 94/95) | s10-orf253* (1264aa, 95/96) | s18-orf17* (1261aa, 94/96) | s03-orf266* (1264aa, 94/96) | s01-orf262* (1261aa, 95/96) | KS/KR/ACP | WP_034382545 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| s14-orf136* (1573aa, 95/97) | s10-orf252* (1575aa, 95/97) | s18-orf18* (1573aa, 95/97) | s03-orf267* (1573aa, 94/96) | s01-orf263* (1567aa, 96/97) | KS/AT/KR/ACP | WP_034382775 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | ||

| pks-2 | – | s04-orf63 (6103aa, 52/62) | s12-orf1 (> 2049aa, 54/63) | s01-orf485 (6202aa, 50/60) | s26-orf2 (5982aa, 56/65) | (KS)/AT/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | See Fig. 1b | AEB44393 | Verrucosispora maris AB-18-032 |

| s47-orf2 (> 3456aa, 53/62) | |||||||||

| s04-orf64 (3854aa, 58/66) | s47-orf1 (> 566aa, 71/78) | s01-orf486 (3774aa, 57/64) | s26-orf1 (> 1579aa, 53/60) | KS/AT(m,e)/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT(m)/DH/ER/KR/ACP | ABW12874 | Frankia sp. EAN1pec | |||

| s02-orf383 (> 1384aa, 66/72) | s02-orf1 (> 2192aa, 63/70) | ||||||||

| s04-orf65 (1070aa, 81/86) | s02-orf382 (997aa, 91/93) | s01-orf487 (1019aa, 87/90) | s02-orf2 (996aa, 89/91) | KS/AT/ACP | WP_030454081 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 | |||

| pks-3 | s12-orf80 (1259aa, 88/92) | – | s09-orf200 (1258aa, 95/96) | s01-orf1205 (1258aa, 94/96) | – | KS/AT?/DH/ACP | ? | WP_030454772 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| pks-4 | – | – | s27-orf91 | s06-orf349 (1795aa, 53/64) | – | KS/AT/ACP/KR/DH | Enediyne | AAP92148 | Actinomadura verrucosospora ATCC 39334 |

| pks-5 | s04-orf1 (> 901aa, 70/79) | s28-orf45 (> 660aa, 64/73) | – | – | – | KS/AT… | See Fig. 1c | WP_018514184 | Streptomyces sp. ScaeMP-e10 |

| s36-orf55 (> 3542aa, 58/67) | s11-orf1 (> 405aa, 54/66) | …ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | WP_032771883 | Streptomyces cyaneofuscatus NRRL B-2570 | |||||

| s11-orf2 (3315aa, 50/61) | |||||||||

| s36-orf54 (2142aa, 66/75) | s11-orf3 (2345aa, 50/62) | KS/AT(m)/DH/KR/ACP | WP_032771870 | Streptomyces cyaneofuscatus NRRL B-2570 | |||||

| pks - 6 | s01-orf132 (1020aa, 52/63) | – | – | – | – | KS/ATm/ACP | See Fig. 1d | EJJ02887 | Streptomyces auratus AGR0001 |

| s01-orf133 (7608aa, 50/61) | KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | WP_035304435 | Actinokineospora inagensis DSM 44258 | ||||||

| s01-orf134 (4820aa, 54/64) | KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | EHY88974 | Saccharomonospora azurea NA-128 | ||||||

| s01-orf135 (6313aa, 52/63) | KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | ACU36619 | Actinosynnema mirum DSM 43827 | ||||||

| s01-orf136 (4533aa, 55/65) | KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | AAX98184 | Streptomyces aizunensis NRRL B-11277 | ||||||

| s01-orf137 (4803aa, 55/65) | KS/ATe(m)/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATe(m)/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | WP_033261216 | Amycolatopsis vancoresmycina NRRL B-24208 | ||||||

| s01-orf138 (5850aa, 54/65) | KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | ABC87511 | Streptomyces sp. NRRL 30748 | ||||||

| s01-orf139 (4995aa, 52/64) | KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | AHH99925 | Kutzneria albida DSM 43870 | ||||||

| s01-orf140 (5337aa, 54/64) | KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP | AEP40936 | Nocardiopsis sp. FU40 | ||||||

| s01-orf141 (3460aa, 57/68) | KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | WP_035796302 | Kitasatospora mediocidica KCTC 9733 | ||||||

| s01-orf142 (4383aa, 54/65) | KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | AAX98186 | Streptomyces aizunensis NRRL B-11277 | ||||||

| s01-orf143 (1247aa, 53/64) | KS/AT/ACP-TE | KIR65900 | Micromonospora carbonacea JXNU-1 | ||||||

| pks - 7 | s20-orf48 (2065aa, 59/68) | – | – | – | – | KS/ATe(m)/ACP-KS/AT/DH/ACP | See Fig. 1e | WP_042439448 | Streptacidiphilus albus NBRC 100918 |

| s20-orf49 (1530aa, 53/63) | KS/AT/KR/ACP | WP_042494385 | Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 = NBRC 14893 | ||||||

| s20-orf50 (2820aa, 62/70) | KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/ACP | CCH32016 | Saccharothrix espanaensis DSM 44229 | ||||||

| s20-orf51 (2064aa, 57/66) | KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-TE | WP_041313683 | Saccharothrix espanaensis DSM 44229 | ||||||

| pks - 8 | – | s08-orf244 (5375aa, 59/69) | – | – | – | KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/ATe(m)/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/DH/KR/ACP | See Fig. 1f | WP_033660827 | Salinispora pacifica CNS237 |

| s08-orf245 (1559aa, 55/66) | KS/AT/KR/ACP | EXU62139 | Streptomyces sp. PRh5 | ||||||

| s08-orf246 (3222aa, 53/65) | KS/ATe(m)/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | EGX61520 | Streptomyces zinciresistens K42 | ||||||

| s08-orf251 (10965aa, 51/63) | KS/AT/ACP-KS/ATe(m)/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATe(m)/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATe(m)/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | ADI03772 | Streptomyces bingchenggensis BCW-1 | ||||||

| s08-orf252 (1565aa, 64/73) | KS/ATm/KR/ACP | WP_033775512 | Salinispora pacifica DSM 45546 | ||||||

| s08-orf253 (3638aa, 59/69) | KS/AT/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP | CAJ88176 | Streptomyces ambofaciens ATCC 23877 | ||||||

| s08-orf254 (7933aa, 67/76) | KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | CAJ88175 | Streptomyces ambofaciens ATCC 23877 | ||||||

| pks - 9 | – | s11-orf206 (7923aa, 54/66) | – | – | – | KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP | See Fig. 1g | BAC68129 | Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 = NBRC 14893 |

| s11-orf207 (1582aa, 54/65) | KS/AT/KR/ACP | WP_032769932 | Streptomyces sp. CNS654 | ||||||

| s11-orf208 (4703aa, 59/69) | KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-TE | CAJ88175 | Streptomyces ambofaciens ATCC 23877 | ||||||

| pks - 10 | – | s26-orf59 (1260aa, 87/92) | – | – | – | KS/AT/ACP | ? | WP_030454772 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

| pks - 11 | – | – | – | – | s22-orf6 (4492aa, 74/80) | KS/AT/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | See Fig. 1i | WP_042397188 | Streptacidiphilus carbonis NBRC 100919 |

| s22-orf5 (6067aa, 75/82) | KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP | WP_042397185 | Streptacidiphilus carbonis NBRC 100919 | ||||||

| s22-orf4 (3381aa, 56/65) | KS/ATm/DH/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP | WP_037075673 | Pseudonocardia spinosispora DSM 44797 | ||||||

| s22-orf3 (6184aa, 71/78) | KA/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP | WP_037075676 | Pseudonocardia spinosispora DSM 44797 | ||||||

| s22-orf2 (6426aa, 76/83) | KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/AT/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/DH/KR/ACP | WP_042408959 | Streptacidiphilus carbonis NBRC 100919 | ||||||

| s22-orf1 (> 4929aa, 77/83) | KS/ATm/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/DH/ER/KR/ACP-KS/ATm/DH… | WP_042408956 | Streptacidiphilus carbonis NBRC 100919 | ||||||

| pks - 12 | – | – | – | – | s02-orf765 (1258aa, 94/95) | KS/AT?/DH/ACP | ? | WP_030454772 | Herbidospora cretacea NRRL B-16917 |

Strain-specific gene clusters are in boldface. NRPS and PKS genes not completely sequenced are shown in italics. C, condensation; A, adenylation; T, thiolation; E, epimerization; MT, methyltransferase; CoL, CoA ligase; KS, ketosynthase; AT, acyltransferase incorporating malonyl-CoA, ATm, acyltransferase incorporating methylmalonyl-CoA; ATe, acyltransferase incorporating ethylmalonyl-CoA; AT?, acyltransferase whose substrate has not been determined by antiSMASH; DH, dehydratase; ER, enoylreductase; KR, ketoreductase; ACP, acyl carrier protein; TE, thioesterase; x, unpredicted amino-acid; mOrn, methyl ornithine; ?, lack of A domain. A domain amino-acid substrate predicted by antiSMASH is shown in subscripted letters

Gene clusters conserved in all the five strains

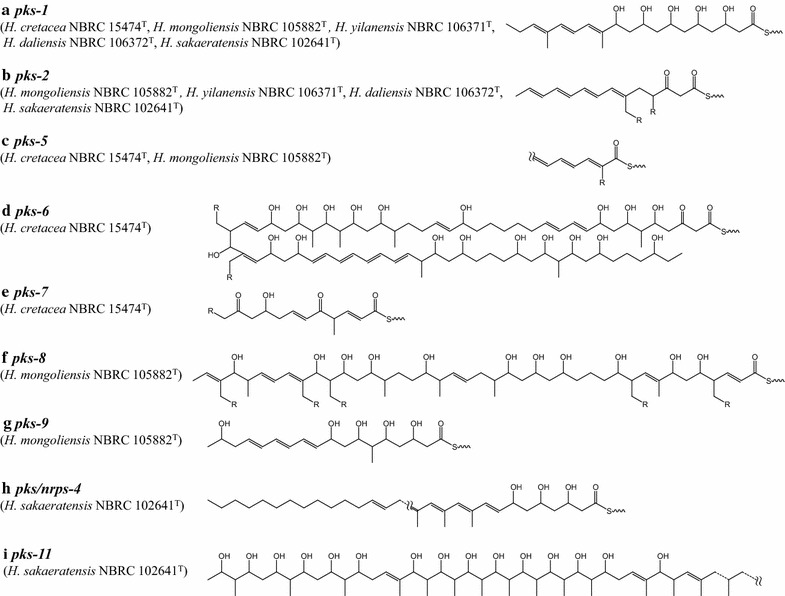

Table 2 suggested that nine presumable products (nrps-1 to -7, pks/nrps-1, pks-1) are common among all five type strains belonging to the genus Herbidospora. Nrps-1 is assumed to be involved in the synthesis of a siderophore similar to albachelin [23], because the module numbers of albachelin NRPS and nrps-1 are the same, and their domain organizations and amino-acid substrates of their A domains are quite similar (albachelin, C/A/T-C/ASer/T/E-C/AOrn/MT/T-C/ASer/T-C/ASer/T-C/A/T/E; NRPS-1, A/MT/T-C/ASer/T-C/AOrn/MT/T-C/A/T-C/ASer/T-C/A/T/E. Distinct domains between them are underlined). Nrps-2 to -6 are predicted to synthesize non-ribosomal peptides comprising 4, 4, 3, 2 and 2 amino acids, respectively, based on their module numbers. Nrps-7 had only a single NRPS module; therefore, we were not able to predict the chemical structure of the product as a peptide. Pks/nrps-1 is a PKS/NRPS hybrid gene encoding a protein comprising three modules for the synthesis of a starter unit, a polyketide unit and an amino-acid unit, respectively. Pks-1 gene clusters contained seven PKS genes, whose assembly line was composed of nine modules. According to the assembly line rule and the substrates of their AT domains, the gene clusters were assumed to synthesize the polyketide chain shown in Fig. 1a. The structure has similar characteristics to those of antifungal polyene compounds, containing multiple carbon–carbon conjugated double bonds and multiple hydroxyl groups.

Fig. 1.

Presumed chemical structures of polyketide backbones synthesized by Herbidospora type-I polyketide synthase (PKS) gene clusters. R=H or methyl. The chemical structures are shown attached to the ACP of the last module by thioester bonds

Gene clusters shared between/among two to four strains

Nrps-8 gene clusters were present in three strains (H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T, H. daliensis NBRC 106372T and H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T). The nrps-8 gene clusters had two modules; therefore, the products were predicted to be dipeptides. Nrps-9 gene clusters present in H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T and H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T possessed five modules. According to the predicted substrates of the A domains in each module, the products would be hexapeptides including glycine (Gly), asparagine acid (Asp), lysine and threonine (Thr) as the building blocks. Nrps-10 and nrps-11 gene clusters were present in H. cretacea NBRC 15474T and H. mongoliensis NBRC 105882T. The nrps-10 gene clusters contained six modules and two A domains were predicted to incorporate serine (Ser) as the substrates; therefore, the products were predicted to be hexapeptides including two Ser molecules. In contrast, nrps-11 had only a single module, and we were not able to predict the peptide product.

Pks-2 gene clusters were present in four strains, with the exception of H. cretacea NBRC 15474T, although those of H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T and H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T were not completely sequenced. The gene clusters contained seven modules, suggesting the products would be molecules derived from C14 polyketide chains. Substrates of AT domains in modules 5 and 6 were predicted to be methylmalonyl-CoA or ethylmalonyl-CoA, and those of all the remaining modules were malonyl-CoA. Four pairs of dehydratase (DH)-ketoreductase (KR) and one trio of DH-enoylreductase (ER)-KR were present as the optional domains in the gene clusters; therefore, four keto groups would be reduced to four conjugated double bonds and one keto group would be completely reduced, respectively. Hence, we predicted the chemical structure of the polyketide backbones shown in Fig. 1b. Pks-3 genes were present in H. cretacea NBRC 15474T, H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T and H. daliensis NBRC 106372T. They contained only a single module and showed low sequence similarities to characterized PKS genes (data not shown); therefore, we were not able to predict the metabolites. Pks-4 genes were present in H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T and H. daliensis NBRC 106372T. They were predicted to be iterative type-I PKSs for enediyne synthesis, called PksE, because they showed higher sequence similarities to PksEs than to normal modular type-I PKSs (data not shown) and included a pair of KR-DH domains, specific for PksE, after the ACP. Their products would be polyketide compounds with an enediyne core [24]. Pks-5 gene clusters were present in H. cretacea NBRC 15474T and H. mongoliensis NBRC 105882T; however, they were not completely sequenced. Hence, we were not able to predict whole chemical structure of the polyketide chain.

Strain-specific clusters

We found 2, 4, 1, 2 and 6 strain-specific NRPS and/or PKS gene clusters in H. cretacea NBRC 15474T, H. mongoliensis NBRC 105882T, H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T, H. daliensis NBRC 106372T and H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T, respectively.

H. cretacea NBRC 15474T possessed 2 specific PKS gene clusters, named pks-6 and pks-7. The pks-6 gene cluster contained 35 modules encoded by 12 PKS genes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest type-I PKS gene cluster ever reported. We predicted the chemical structure of the polyketide backbone synthesized by pks-6, as shown in Fig. 1d, which is most likely a novel compound because no similar compounds were found in our database searches. The pks-7 gene cluster contained 6 modules encoded by 4 PKS genes and we predicted the metabolites to be hexaketide compounds with 2 C–C double bonds and one hydroxyl group.

H. mongoliensis NBRC 105882T possessed a specific PKS/NRPS gene cluster and 3 specific PKS gene clusters, named pks/nrps-2, pks-8, pks-9 and pks10. Pks/nrps-2 contained 1 PKS module and 13 NRPS modules, encoded by a PKS gene and seven NRPS genes, respectively. According to the module numbers and the A domain substrates, the product was predicted to be large polyketide-non-ribosomal peptide hybrid compound including Ser, Thr and asparagine (Asn). The pks-8 gene cluster contained seven PKS genes encoding 21 modules. As shown in Fig. 1f, its products would be large polyketide compounds with 6 C–C double bonds and 11 hydroxyl groups. The pks-9 contained 3 PKS genes encoding 9 modules. Its products were predicted to be nonaketide compounds with 3 conjugated double bonds and 5 hydroxyl groups (Fig. 1g). The pks-10 gene encoded only a single module; therefore, we were not able to predict the chemical structure of its metabolite.

H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T possessed a specific PKS/NRPS hybrid gene cluster named pks/nrps-3. The products were predicted to be polyketide-non-ribosomal peptide hybrid compounds whose backbone is leucine (Leu)-valine (Val)-Leu-Ser-a polyketide unit.

H. daliensis NBRC 106372T possessed 2 specific NRPS gene clusters, named nrps-12 and nrps-13. The nrps-12 gene cluster encoded 22 modules, the products of which were predicted to be peptide compounds comprising 22 amino-acids, including 2 phenylalanine (Phe), 7 Asp, 1 Ser, 1 Val, 3 tyrosine (Tyr), and 1 Asn molecules. In contrast, nrps-13 contained only two modules, whose A domains were predicted to incorporate Gly and Ala, respectively. Hence, the products will be dipeptides including Gly and Ala molecules.

H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T possessed 3 specific NRPS gene clusters, one specific PKS/NRPS hybrid gene cluster and two specific PKS gene clusters named nrps-14 to -16, pks/nrps-4, pks-11 and pks-12. In the nrps-14 gene cluster, three NRPS genes were present encoding six modules. The A domains of four modules were predicted to incorporate Val, Ser, Asn and Asn, suggesting that nrps-14 would produce hexapeptides including Val, Ser and two Asn molecules. Nrps-15 had only one module, but the domain organization (A-C-T) was different from that of normal NRPS (C-A-T). Because a CoA-ligase, an ACP, and an NRPS comprising only one C domain were also encoded adjacent to nrps-15 gene (data not shown), this gene cluster might synthesize compounds composed of a starter molecule and a Gly molecule loaded by the unusual NRPS. Nrps-16 also had only a single module; therefore, we were not able to predict its peptide products. The pks/nrps-4 gene cluster encoded at least 15 PKS modules and one NRPS module, but it was not completely sequenced because the sequence of a PKS gene named s08-orf1 was partial and the adjacent genes remain unclear. Although we were not able to predict the whole chemical structure synthesized by this gene cluster, the product will include a C28 or longer polyketide chain. The pks-11 gene cluster encoded at least twenty modules, although s22-orf1 was not completely sequenced and the adjacent genes were unclear. This product was predicted to be a large compound including a polyhydroxyl polyketide chain, as shown in Fig. 1i. The pks-12 gene cluster encoded only a single module; therefore, we were not able to predict chemical structures of its products.

Distribution and evolutionary history of NRPS and PKS gene clusters

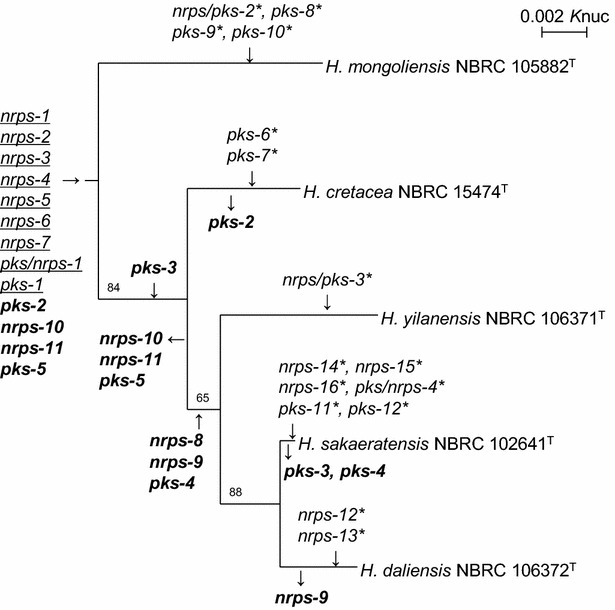

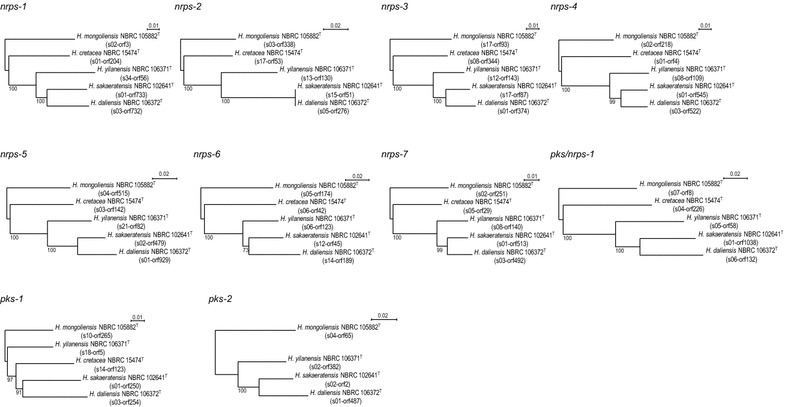

We constructed a phylogenetic tree of the type strains of the genus Herbidospora based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. By mapping the inferred ancestral nodes of the individual gene clusters onto the tree, we traced the evolutionary histories of these pathways (Fig. 2). Nine gene clusters, underlined in Fig. 2, appeared to have been acquired early in the evolution of the genus Herbidospora, because they are conserved in all the type strains. By contrast, 15 gene clusters, indicated by asterisks in Fig. 2, would have been acquired relatively recently, appearing toward the branch terminals in the tree. Gene clusters shared between/among 2–4 strains are in boldface in Fig. 2. Pks-2 gene clusters are present in 4 strains, except for H. cretacea NBRC 15474T, suggesting they were acquired early, and inherited vertically; however, they were lost just before evolution to H. cretacea. The nrps-10, nrps-11 and pks-5 clusters are present in H. mongoliensis NBRC 105882T and H. cretacea NBRC 15474T, but not in the other 3 strains, we speculated that these 3 gene clusters were acquired early, but lost just before evolution to H. yilanensis, H. sakaeratensis and H. daliensis. The pks-3 gene clusters are present in three strains except for H. mongoliensis NBRC 105882T and H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T, suggesting that they were acquired just branching off from H. mongoliensis and lost just before evolution to H. sakaeratensis. Nrps-8 gene clusters are present in H. yilanensis NBRC 106371T, H. sakaeratensis NBRC 102641T and H. daliensis NBRC 106372T, suggesting acquisition just before evolution to these three species. Similarly, the nrps-9 and pks-4 gene clusters would also have been acquired at the same point; however, these clusters seemed to have been lost during evolution to H. daliensis and H. sakaeratensis, respectively. To confirm the hypothesis, we conducted phylogenetic analysis of NRPSs and PKSs in gene clusters conserved among more than 4 strains. Except for pks-1, all the phylogenetic trees showed the same topology (Fig. 3) as that based on 16S rDNA sequences (Fig. 2). This supports that nrps-1 to -7, pks/nrps-1 and pks-2 were actually acquired early in the evolution and inherited vertically. In contrast, pks-1 may not be inherited in the same manner as these gene clusters, because the topology of pks-1 phylogenetic tree differed from those of other gene clusters and 16S rDNA sequence.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the type strains of the genus Herbidospora, based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, depicting the inferred ancestry of NRPS and PKS gene clusters. Bootstrap values (>50 %) from 1000 replicates are shown at branch nodes. Arrows indicate acquisitions and losses of NRPS and PKS gene clusters. Gene clusters conserved all the five strains, shared between/among two to four strains, and specific to each strain are underlined, boldfaced, and asterisked, respectively

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the type strains of the genus Herbidospora, based on NRPS and PKS sequences. Bootstrap values (>50 %) from 1000 replicates are shown at branch nodes. The proteins used in this analysis are shown in parentheses by open reading frame numbers listed in Table 2

Conclusions

We concluded the following: (1) The genomes of Herbidospora strains carry as many NRPS and PKS gene clusters as those of other actinomycetes such as Streptomyces; however, their products are yet to be isolated; (2) members of the genus Herbidospora can synthesize large and diverse metabolites, many of whose chemical structures are yet to be reported; (3) each strain possesses 1–6 strain-specific NRPS and/or PKS gene clusters, in addition to those conserved within this genus, suggesting diversity of these pathways; and (4) the diversity of NRPS and PKS pathways in each strain has increased by genus-level vertical inheritance and relatively recent acquisitions of these gene clusters during evolution of this genus.

To summarize, in this study, we sequenced whole genomes of all the five type strains belonging to the genus Herbidospora and examined their NRPS and PKS gene clusters. Each strain harbored 15–18 modular NRPS and PKS gene clusters. Through the comparison of these gene clusters, 32 NRPS and PKS pathways were identified from the 5 strains. Among them, 9 pathways were conserved in all 5 strains, 8 were shared in 2–4 strains, and the remaining 15 were strain-specific suggesting the strain diversity of these pathways. We revealed that these strains harbor a wealth of NRPS and PKS pathways, many of whose products are large and have yet to be discovered. This study also provided useful information about the inferred numbers and molecular structures of secondary metabolites, such as non-ribosomal peptides and polyketides, potentially produced by these strains, suggesting that Herbidospora strains are an untapped and attractive source of novel secondary metabolites.

Authors’ contributions

HK analyzed the NRPS and PKS gene clusters and wrote the manuscript. NI annotated the NRPS and PKS genes. AO performed the genome sequencing. MH and TT designed the genome sequencing of Herbidospora strains. NF organized the sequencing project and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ms. Yuko Kitahashi for finishing the genome sequences and annotating the NRPS and PKS genes. We also thank Ms. Tomoko Hanamaki for assistance with whole-genome sequencing.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- NBRC

Biological Resource Center, National Institute of Technology and Evaluation

- NRPS

non-ribosomal peptide synthetase

- PKS

polyketide synthase

- C

condensation

- A

adenylation

- T

thiolation

- KS

ketosynthase

- AT

acyltransferase

- ACP

acyl carrier protein

- CoA

coenzyme A

- Ser

serine

- E

epimeration

- Orn

ornithine

- MT

methylation

- Gly

glycine

- Asp

asparagine acid

- Thr

threonine

- DH

dehydratase

- KR

ketoreductase

- ER

enoylreductase

- Asn

asparagine

- Leu

leucine

- Val

valine

- Phe

phenylalanine

- Tyr

tyrosine

Contributor Information

Hisayuki Komaki, Phone: +81-438-20-5764, Email: komaki-hisayuki@nite.go.jp.

Natsuko Ichikawa, Email: ichikawa-natsuko@nite.go.jp.

Akio Oguchi, Email: oguchi-akio@nite.go.jp.

Moriyuki Hamada, Email: hamada-moriyuki@nite.go.jp.

Tomohiko Tamura, Email: tamura-tomohiko@nite.go.jp.

Nobuyuki Fujita, Email: fujita-nobuyuki@nite.go.jp.

References

- 1.Berdy J. Bioactive microbial metabolites. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2005;58(1):1–26. doi: 10.1038/ja.2005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watve MG, Tickoo R, Jog MM, Bhole BD. How many antibiotics are produced by the genus Streptomyces? Arch Microbiol. 2001;176(5):386–390. doi: 10.1007/s002030100345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazzarini A, Cavaletti L, Toppo G, Marinelli F. Rare genera of actinomycetes as potential producers of new antibiotics. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2000;78(3–4):399–405. doi: 10.1023/A:1010287600557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ara I, Tsetseg B, Daram D, Suto M, Ando K. Herbidosporamongoliensis sp. nov., isolated from soil, and reclassification of Herbidosporaosyris and Streptosporangiumclaviforme as synonyms of Herbidosporacretacea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62(Pt 10):2322–2329. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.037861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boondaeng A, Suriyachadkun C, Ishida Y, Tamura T, Tokuyama S, Kitpreechavanich V. Herbidosporasakaeratensis sp. nov., isolated from soil, and reclassification of Streptosporangiumclaviforme as a later synonym of Herbidosporacretacea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;61(Pt 4):777–780. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.024315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kudo T, Itoh T, Miyadoh S, Shomura T, Seino A. Herbidospora gen. nov., a new genus of the family Streptosporangiaceae Goodfellow et al. 1990. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43(2):319–328. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-2-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseng M, Yang SF, Yuan GF. Herbidosporayilanensis sp. nov. and Herbidosporadaliensis sp. nov., from sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60(Pt 5):1168–1172. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.014803-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nett M, Ikeda H, Moore BS. Genomic basis for natural product biosynthetic diversity in the actinomycetes. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26(11):1362–1384. doi: 10.1039/b817069j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komaki H, Ichikawa N, Hosoyama A, Takahashi-Nakaguchi A, Matsuzawa T, Suzuki K, Fujita N, Gonoi T. Genome based analysis of type-I polyketide synthase and nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene clusters in seven strains of five representative Nocardia species. BMC Genom. 2014;15:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komaki H, Ichikawa N, Oguchi A, Hanamaki T, Fujita N. Genome-wide survey of polyketide synthase and nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene clusters in Streptomycesturgidiscabies NBRC 16081. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2012;58(5):363–372. doi: 10.2323/jgam.58.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106(8):3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohtsubo Y, Maruyama F, Mitsui H, Nagata Y, Tsuda M. Complete genome sequence of Acidovorax sp. strain KKS102, a polychlorinated-biphenyl degrader. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(24):6970–6971. doi: 10.1128/JB.01848-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blin K, Medema MH, Kazempour D, Fischbach MA, Breitling R, Takano E, Weber T. antiSMASH 2.0–a versatile platform for genome mining of secondary metabolite producers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Web Server issue):W204–W212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NBRC Culture Catalogue: http://www.nbrc.nite.go.jp/NBRC2/NBRCDispSearchServlet?lang=en.

- 16.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felsenstein J. Limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39(4):783–791. doi: 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, Harris DE, Quail MA, Kieser H, Harper D, et al. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomycescoelicolor A3(2) Nature. 2002;417(6885):141–147. doi: 10.1038/417141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bignell DR, Seipke RF, Huguet-Tapia JC, Chambers AH, Parry RJ, Loria R. Streptomycesscabies 87-22 contains a coronafacic acid-like biosynthetic cluster that contributes to plant-microbe interactions. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2010;23(2):161–175. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-2-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, Hanamoto A, Shinose M, Kikuchi H, Shiba T, Sakaki Y, Hattori M, Omura S. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the industrial microorganism Streptomycesavermitilis. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(5):526–531. doi: 10.1038/nbt820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohnishi Y, Ishikawa J, Hara H, Suzuki H, Ikenoya M, Ikeda H, Yamashita A, Hattori M, Horinouchi S. Genome sequence of the streptomycin-producing microorganism Streptomycesgriseus IFO 13350. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(11):4050–4060. doi: 10.1128/JB.00204-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kodani S, Komaki H, Suzuki M, Hemmi H, Ohnishi-Kameyama M. Isolation and structure determination of new siderophore albachelin from Amycolatopsis alba. Biometals. 2015;28(2):381–389. doi: 10.1007/s10534-015-9842-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Ji R, Jiang X, Yang R, Liu F, Xin Y. Iterative type I polyketide synthases involved in enediyne natural product biosynthesis. IUBMB Life. 2014;66(9):587–595. doi: 10.1002/iub.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]