Abstract

Background

The prognostic significance of premature atrial complex (PAC) burden is not fully elucidated. We aimed to investigate the relationship between the burden of PACs and long-term outcome.

Methods and Results

We investigated the clinical characteristics of 5371 consecutive patients without atrial fibrillation (AF) or a permanent pacemaker (PPM) at baseline who underwent 24-hour electrocardiography monitoring between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2004. Clinical event data were retrieved from the Bureau of National Health Insurance of Taiwan. During a mean follow-up duration of 10±1 years, there were 1209 deaths, 1166 cardiovascular-related hospitalizations, 3104 hospitalizations for any reason, 418 cases of new-onset AF, and 132 PPM implantations. The optimal cut-off of PAC burden for predicting mortality was 76 beats per day, with a sensitivity of 63.1% and a specificity of 63.5%. In multivariate analysis, a PAC burden >76 beats per day was an independent predictor of mortality (hazard ratio: 1.384, 95% CI: 1.230 to 1.558), cardiovascular hospitalization (hazard ratio: 1.284, 95% CI: 1.137 to 1.451), new-onset AF (hazard ratio: 1.757, 95% CI: 1.427 to 2.163), and PPM implantation (hazard ratio: 2.821, 95% CI: 1.898 to 4.192). Patients with frequent PAC had increased risk of mortality attributable to myocardial infarction, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death. Frequent PACs increased risk of PPM implantation owing to sick sinus syndrome, high-degree atrioventricular block, and/or AF.

Conclusions

The burden of PACs is independently associated with mortality, cardiovascular hospitalization, new-onset AF, and PPM implantation in the long term.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, permanent pacemaker, premature atrial complex, sick sinus syndrome

Premature atrial complex (PAC) is a highly prevalent arrhythmia that is associated with a high incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) and subsequent complications.1–4 The burden of PACs in the general population can be independently associated with many predisposing factors, such as increased age, abnormal body height, cardiovascular (CV) disease, abnormal levels of natriuretic peptide, and abnormal levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.3 Several studies have demonstrated an increased incidence of ischemic stroke and composite CV events in patients with a high PAC burden.2,5 Normal functioning of the sinus and atrioventricular nodes can be disturbed by atrial extrastimuli.6,7 Adverse sinus node remodeling can be reversed after frequent atrial extrastimuli are eliminated in patients with sinus node dysfunction.8 These findings suggest that the burden of PACs may adversely affect sinus and atrioventricular node function as a result of abnormal electrical stimulation, leading to subsequent substrate remodeling. However, the clinical significance of PAC burden on the risks of mortality, morbidity, and dysfunctions of the cardiac conduction system has not been fully elucidated. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the clinical impact of PAC burden, based on 24-hour electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring, on mortality, CV hospitalization, occurrence of new-onset AF, and the need for permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation during a long-term clinical follow-up.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The Institutional Review Board at Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan approved this study without requiring patients’ informed consent (VGH-IRB Number: 2013-08-002AC#1). The patient records/information was anonymous and de-identified prior to analysis.

Study Population

This retrospective, observational study was based on information obtained from the “Registry of 24-hour ECG monitoring at Taipei Veterans General Hospital” database. Taipei Veterans General Hospital is a large integrated healthcare delivery system providing comprehensive medical services to a population of more than 3 million in Taiwan. The study group included 5903 consecutive patients who were more than 18 years of age and who underwent clinically indicated 24-hour ECG monitoring between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2004 at the Taipei Veterans General Hospital. Patients were referred for Holter monitoring for indications including palpitations, syncope, suspected arrhythmia, and clinical follow-up according to the physician’s discretion. Collected variables, including past medical history, risk factors, comorbidities, and medications, were obtained from 1 or more primary or secondary hospital discharge diagnoses, outpatient visits, emergency visits, and the Collaboration Center of Health Information Application, Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes were used as surrogates for other underlying diseases before 24-hour ECG monitoring. The diagnoses must have been recorded twice in outpatient department records, or at least once in inpatient records. Participants with AF and/or atrial flutter (baseline 12-lead ECG or on baseline Holter monitoring), a PPM (confirmed as a reported history of the presence of a PPM at their first study encounter on baseline 12-lead ECG or apparent on baseline Holter monitoring), or a history of ablation were excluded. The final sample included 5371 patients. A medical history including details of baseline CV comorbid conditions and physical examination were retrospectively reviewed based on existing records. In our previous studies, we have validated this methodology.9,10

Follow-Up and Outcomes

Follow-up visits of all participants were scheduled depending on their clinical course or after each new event in this study. Patients with regular medication were scheduled for regular follow-up with an interval of 1 to 3 months. After the documentation of each new event, patient follow-up was conducted every 2 weeks for 1 month and then at intervals of 1 to 3 months. Patients without regular medication were scheduled for follow-up after 1 year or after any new events at the discretion of their physician. Follow-up data were retrieved from the Taipei Veterans General Hospital or from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. The Taiwan National Health Insurance program has 23 million people enrolled, and this accounts for 99% of the country’s population. The insurance claim database can be used for studies of the natural history of diseases and for clinical research involving actual clinical situations. In this cohort dataset, the original identification number of each patient is encrypted to ensure their privacy. The encryption procedure is such that a linkage of the claims belonging to a given patient is feasible within the National Health Insurance database and allows for continuous tracking. The main outcomes determined were death, hospitalization for any reason (all-cause hospitalization), hospitalization for CV-related conditions (CV hospitalization), occurrence of new-onset AF, and PPM implantation. Potential new incident events, any inpatient admissions, and all deaths were investigated in detail based on initial identification through the International Classification of Diseases diagnostic codes or mention of an end point on the hospital face sheet, previous discharge summary, outpatient clinic report, and/or the Collaboration Center of Health Information Application database. This methodology has been previously validated.11–13 Hospitalization was defined as an overnight stay in a hospital ward, excluding evaluation in the emergency department. New-onset heart failure and new-onset AF were confirmed by physician reports, documented echocardiography reports, ECG reports, by medical record review during regular clinical visits, or as a result of mention of such an end point on either the hospital face sheet or the discharge summary. The follow-up period was from the date of patient registration through February 28, 2013.

Risk Factors

Data were collected based on demographic characteristics (age and sex) from the medical records of patients. Targeted comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, history of myocardial infarction, and valvular heart disease, were determined by using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes from the medical record at the time of examination. Left ventricular ejection fraction data were collected from the echocardiography reports. The New York Heart Association functional classification and medication data were determined from the medical and nursing records.

Statistical Methods

All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software, version 20.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). Baseline patient characteristics are reported as the mean±SD for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. Receiver operator characteristic curves and areas under the receiver operator characteristic curves were analyzed to determine the optimal cut-off point for all-cause death (Youden index). The final results indicated an optimal cut-off point of 76 beats of PACs on 24-hour ECG monitoring (76 beats per day) as a predictor for an adverse outcome. Baseline characteristics of the patients with a PAC burden >76 beats per day and those with a PAC burden ≤76 beats per day were compared using Student t test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. An α error of <5% was considered statistically significant. Crude event rates from the 10-year Kaplan–Meier survival curves were compared between the 2 groups using the log-rank test for a given end point.

The relative risk for a given end point associated with PAC burden was estimated by calculating the hazard ratio (HR) using a Cox regression hazards model. This model was run with all parameters that had an α error of <0.05 in their baseline data (age, sex, hypertension, coronary artery disease, previous myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, and use of antihypertension medication). Different end-point comparisons between the 2 groups for death and indication for PPM implantation were performed using the χ2 test for categorical variables. The HRs of PACs in different subgroups of patients with individual risk factors are shown in a Forest plot (Figure 3). Propensity-score matching was also used to control for all confounders.14 The propensity score was obtained by using logistic regression. A Cox proportional hazards model was applied to examine the risk of frequent PACs (PAC burden >76 beats per day) in the propensity-matched samples. To determine whether inclusion of PACs in the model improved the predictive power, discrimination tests were performed with the integrated discrimination.14 For the old model, clinical outcome markers (age, sex, hypertension, coronary artery disease, previous myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, and use of antihypertension medication) were used.

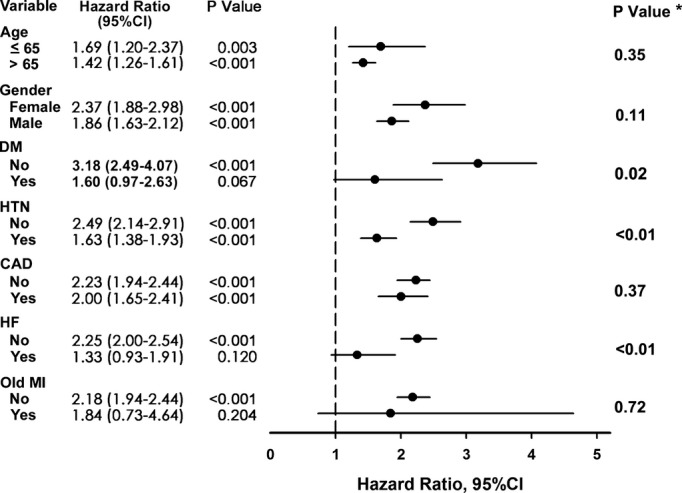

Figure 3.

Forest plot for subgroup analysis for all-cause mortality. Hazard ratio of PAC >76 beats per day group compared with PAC ≤76 beats per day group in different subgroups of patients with individual risk factors. *P value for the PACs burden by each stratification variables interaction. CAD indicates coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; PAC, premature atrial complex.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

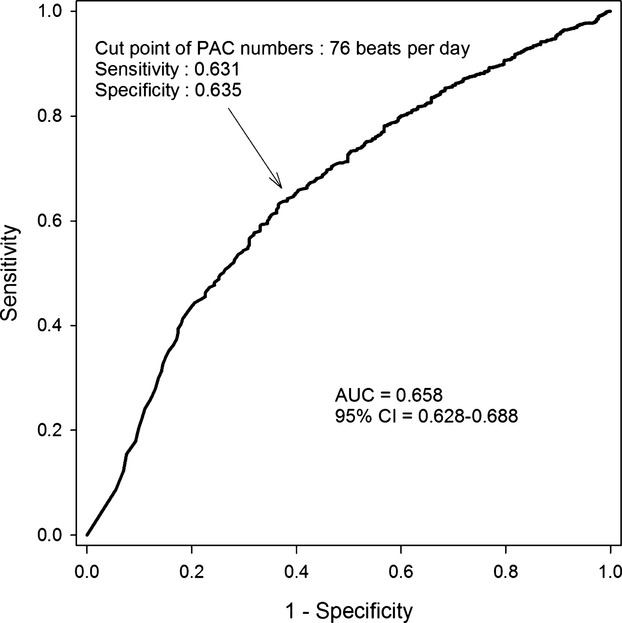

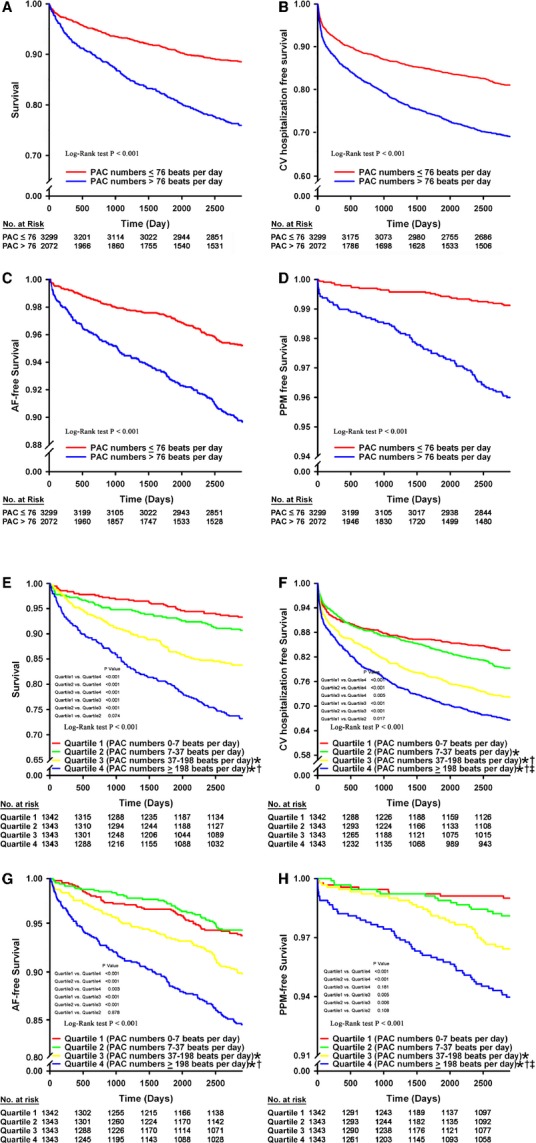

The 5371 patients in this study were followed up for 10±1 years through clinical evaluation and investigation of medical records, nursing records, and Bureau of National Health Insurance of Taiwan data. During the follow-up period, there were 1209 (22.5%) deaths, 3104 (57.8%) all-cause hospitalizations, 1166 (21.7%) CV hospitalizations, 418 (7.8%) cases of new-onset AF, and 132 (0.25%) PPM implantations. The optimal cut-off for PAC beats per 24 hours for predicting mortality was 76 beats per day, with a sensitivity of 63.1% and specificity of 63.5% (area under the receiver operator characteristic curve: 65.6%, Figure 1). On the basis of the optimal cut-off for predicting mortality, a PAC burden >76 beats per day was defined as “frequent PACs.” Figure 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier survival curve and CV hospitalization-free, AF-free, and PPM-free survival in patients with or without frequent PACs. The baseline characteristics of patients with and without frequent PACs are presented in Table 1. Patients with frequent PACs were generally older and male, with a higher incidence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, history of myocardial infarction, and more medications for hypertension compared to the group without frequent PACs.

Figure 1.

ROC curve survival analysis by PAC numbers. The optimal cut-off of PAC burden for predicting mortality was 76 beats per day (Youden index), with a sensitivity of 63.1% and specificity of 63.5%. AUC indicates area under the curve; PAC, premature atrial complex; ROC, receiver operator characteristic.

Figure 2.

Impact of PAC burden on survival, CV hospitalization, new-onset AF, and PPM implantation. A, Patient survival of PAC ≤76 beats per day group compared with PAC >76 beats per day group (P<0.001 by log-rank test). B, Patient CV hospitalization-free survival of PAC ≤76 beats per day group compared with PAC >76 beats per day group (P<0.001 by log-rank test). C, Patient AF-free survival of PAC ≤76 beats per day group compared with PAC >76 beats per day group (P<0.001 by log-rank test). D, Patient PPM-free survival of PAC ≤76 beats per day group compared with PAC >76 beats per day group (P<0.001 by log-rank test). E, Patient survival of PAC burden in quartile comparison (P<0.001 by log-rank test). F, Patient CV hospitalization-free survival of PAC burden in quartile comparison (P<0.001 by log-rank test). G, Patient AF-free survival of PAC burden in quartile comparison (P<0.001 by log-rank test). H, Patient PPM-free survival of PAC burden in quartile comparison (P<0.001 by log-rank test). *P<0.05 in comparison with Quartile 1; †P<0.05 in comparison with Quartile 2; ‡P<0.05 in comparison with Quartile 3. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CV, cardiovascular; PAC, premature atrial complex; PPM, permanent pacemaker.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of All Patients

| All | PAC ≤76/day | PAC >76/day | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=5371 | n=3299 | n=2072 | P Value | |

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean±SD | 61.76±18.57 | 56.55±18.29 | 70.06±15.79 | <0.001 |

| Men | 3222 (60.0) | 1765 (53.5) | 1457 (70.3) | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 28 (0.5) | 18 (0.5) | 10 (0.5) | 0.755 |

| Prior MI | 31 (0.6) | 13 (0.4) | 18 (0.9) | 0.025 |

| Valvular heart disease | 103 (1.9) | 68 (2.1) | 35 (1.7) | 0.359 |

| Cardiovascular risk factor | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 530 (20.2) | 299 (9.1) | 231 (11.1) | 0.013 |

| Hypertension | 1911 (35.6) | 989 (30.0) | 922 (44.5) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 687 (12.8) | 467 (9.4) | 220 (10.5) | 0.298 |

| Heart failure | 253 (4.7) | 127 (3.8) | 126 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| LVEF | 44.59±13.06 | 43.71±13.40 | 45.49±12.70 | 0.118 |

| NYHA I | 135 (53.4) | 67 (52.8) | 68 (54.0) | 0.847 |

| NYHA II | 59 (23.3) | 28 (22.0) | 31 (24.6) | 0.631 |

| NYHA III | 57 (22.5) | 30 (23.6) | 27 (21.4) | 0.676 |

| NYHA IV | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.157 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1580 (29.4) | 875 (26.5) | 705 (34.0) | <0.001 |

| CKD | 57 (1.1) | 30 (0.9) | 27 (1.3) | 0.174 |

| Congenital heart disease | 6 (1.1) | 5 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | 0.270 |

| Medication | 621 (11.6) | 348 (10.5) | 273 (13.2) | 0.003 |

| Anti-arrhythmia* | 28 (0.5) | 13 (0.4) | 15 (0.7) | 0.102 |

| Anti-hypertension† | 1050 (19.5) | 526 (16.0) | 524 (25.2) | <0.001 |

| PAC, mean±SD | 252±565 | 19±20 | 643±780 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up, days | 3334±221 | 3332±221 | 3338±221 | 0.377 |

Values are number of events (%) unless otherwise indicated. CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAC, premature atrial complex.

Class I or class III antiarrhythmic drugs.

Dihydropyrimidine calcium channel blocker, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blocker, diuretics, β-blocker, and α-blocker.

PACs and Long-Term Outcomes

Patients with frequent PACs had higher rates of all-cause mortality, all-cause hospitalization, CV hospitalization, new-onset AF, and PPM implantation compared to patients without frequent PACs (Table 2). After multivariate adjustment for baseline risk factors, the clinical event rates remained higher in patients with frequent PACs, with an estimated HR (95% CI) of 1.384 (1.230 to 1.558) for all-cause mortality, 1.284 (1.137 to 1.451) for CV hospitalization, 1.757 (1.427 to 2.163) for new-onset AF, and 2.821 (1.898 to 4.192) for PPM implantation.

Table 2.

Ten-Year Event Rates in Patients With and Without PAC >76 Beats Per Day

| PAC ≤76/day | PAC >76/day | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | n=3299 | n=2072 | Crude HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted P Value | HR (95% CI) of Each Quartile | P Value |

| All-cause death | 538 (16.3) | 671 (32.4) | 2.188 (1.953 to 2.451) | <0.001 | 1.384 (1.230 to 1.588)* | <0.001 | 1.660 (1.487 to 1.853) | <0.001 |

| All-cause admission | 1740 (52.7) | 1364 (65.8) | 1.436 (1.338 to 1.542) | <0.001 | 1.060 (0.983 to 1.143)* | 0.127 | 1.217 (1.177 to 1.258) | <0.001 |

| CV-cause admission | 575 (17.4) | 591 (28.5) | 1.744 (1.555 to 1.957) | <0.001 | 1.284 (1.137 to 1.451)* | <0.001 | 1.311 (1.240 to 1.386) | <0.001 |

| New-onset AF | 176 (5.3) | 242 (11.7) | 2.305 (1.898 to 2.799) | <0.001 | 1.757 (1.427 to 2.163)* | <0.001 | 1.452 (1.319 to 1.598) | <0.001 |

| PPM implantation | 37 (1.1) | 95 (4.6) | 4.139 (2.831 to 6.052) | <0.001 | 2.821 (1.898 to 4.192)* | <0.001 | 1.760 (1.466 to 2.113) | <0.001 |

Values are number of events (%) unless otherwise indicated. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CV, cardiovascular; HR, hazard ratio; PAC, premature atrial complex; PPM, permanent pacemaker.

HRs were adjusted for patient age, sex, hypertension, coronary heart disease, previous myocardial infarction, heart failure, and use of antihypertension medication.

We performed a propensity-matched multivariable logistic regression analysis to control for all confounders. A propensity-matched score was assigned to each patient in our study, which reflected the propensity for experiencing the exposure of interest. A Cox proportional hazards model was applied to examine the risk of frequent PACs in propensity-matched samples. The HR (95% CI) of frequent PACs for mortality was still significantly elevated (Tables S1 and Tables S2).

We further divided the 5371 patients into quartiles, according to their PAC burdens. Cut-off points for the first, second, and third quartiles were 7, 37, and 198 beats per day, respectively. Subgroup comparisons for incidence of mortality, CV hospitalization, new-onset AF, and PPM implantation are shown in Figure 2. The incidence rates for mortality, new-onset AF, and need for PPM implantation were significantly higher in quartiles 3 and 4, but not in quartile 2. The CV hospitalization rate was significantly higher in quartiles 2, 3, and 4. The risk increased significantly in each quartile. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with the log-rank test for subgroup analysis revealed significant differences between survival curves. All pairwise multiple-comparison procedures (Holm–Sidak method) revealed that quartile 4 was significantly different compared to the other quartiles. Quartile 3 was significantly different when compared to quartiles 1 or 2.

Predictors of Risk

The outcome markers (age, sex, hypertension, coronary artery disease, previous myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, and use of antihypertension medication) for our study were used for the old model. When PAC burden was added to other variables for estimates of risk, the integrated discrimination was 0.0108 (P<0.001) for mortality, 0.0065 (P<0.001) for CV hospitalization, 0.0103 (P<0.001) for PPM implantation, and 0.0095 (P<0.001) for new-onset AF.

Subgroup Analysis

Figure 3 shows the Forest plot estimates of HRs for mortality in each subgroup with or without frequent PACs. Patients with frequent PACs were at higher risk of mortality in subgroup analyses of age, gender, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. However, the higher risk of mortality in frequent PACs was observed in patients without history of heart failure or old myocardial infarction. Patients with history of heart failure or old myocardial infarction may have higher mortality caused by the disease itself, which may diminish the influence of PAC. In the different end-point analyses of all-cause mortality, frequent PACs were associated with death due to infection and CV events (Table 3). When CV events were further divided into myocardial infarction, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death, frequent PAC was associated with all 3 events. In the different end-point analyses for the indication of PPM implantation, frequent PAC was associated with sick sinus syndrome, high-degree atrioventricular block, and AF (Table 3). Frequent PACs were not associated with ventricular tachycardia or any other indication. In terms of sick sinus syndrome as an indication for PPM, the etiology of sick sinus syndrome included long pause, tachy-brady syndrome, and sinus bradycardia. Frequent PACs were significantly associated with long pause and tachy-brady syndrome as an indication for PPM, but were not associated with sinus bradycardia.

Table 3.

Cause of Death and Indication of PPM

| PAC ≤76/day | PAC >76/day | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n=3299 | n=2072 | P Value | |

| Cause of death | |||

| Infection | 40 (1.2) | 96 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 63 (1.9) | 52 (2.5) | 0.348 |

| CV | 129 (3.9) | 162 (7.8) | <0.001 |

| HF | 7 (0.2) | 19 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| MI | 30 (0.9) | 36 (1.7) | 0.015 |

| SCD | 3 (0.1) | 13 (0.6) | 0.001 |

| Neurologic | 7 (0.2) | 11 (0.5) | 0.086 |

| Indication of PPM | |||

| SSS | 20 (0.6) | 58 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Long pause | 16 (0.5) | 48 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Tachy-brady | 3 (0.1) | 8 (0.4) | 0.003 |

| Bradycardia | 1 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0.563 |

| AVB | 13 (0.4) | 23 (1.1) | 0.001 |

| VT | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 0.852 |

| AF or PAF | 3 (0.1) | 6 (0.3) | 0.041 |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; AVB, atrioventricular block; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; PAC, premature atrial complex; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; PPM, permanent pacemaker; SCD, sudden cardiac death; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; Tachy-brady, tachy-brady syndrome; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that patients with a PAC burden >76 beats per day were at increased risk for mortality, CV hospitalization, AF, and PPM implantation. In the subgroup analysis of all-cause mortality, frequent PACs were associated with death due to infection and CV events. Frequent PACs correlated closely with PPM implantation caused by sick sinus syndrome, high-degree atrioventricular block, and AF.

PAC and Mortality

After adjusting for various potential confounding factors, we found that a PAC burden >76 beats per day was associated with increments in the incidence of all-cause mortality (HR [95% CI]: 1.384 [1.230 to 1.558]), CV hospitalization (1.284 [1.137 to 1.451]), new-onset AF (1.757 [1.427 to 2.163]), and PPM implantation (2.821 [1.898 to 4.192]). In a previous study, risks of death, stroke, and AF were significantly increased in healthy subjects with a PAC burden >720 beats per day during a 6.3-year follow-up study.1 Another 16.4-year follow-up study of subjects from the general population without a history of stroke or coronary heart disease found that the presence of PACs in a 2-minute rhythm strip was correlated with (fatal or nonfatal) coronary heart disease, but not with sudden cardiac death.15 One 14-year follow-up study reveals that presence of PACs in 12-lead ECG was a strong predictor of AF development, and was associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease in the general population.16 Another prospective cohort study found that the addition of PAC count (>32 beats/hour) to a validated AF risk algorithm by the Framingham model provides superior AF risk discrimination and significantly improves risk reclassification in 15-year follow-up.17 Recently, the presence of frequent PACs (>100 beats per day) in symptomatic patients without AF or structural heart disease was shown to increase the risks of developing AF, ischemic stroke, heart failure, and death during a 6.1-year follow-up study.3 Frequent PACs could predispose an individual to new-onset AF, ischemic stroke, and heart failure, which, in turn, increase the risks of CV hospitalization and mortality.18–21 Increments in such pathological conditions may contribute, at least in part, to the observed increases in hospital admissions and mortality rate. Results of comparison of 4 quartiles based on PAC burdens, the risk of mortality, CV hospitalization, AF incidence, and PPM implantation were directly proportional to PAC burdens. However, there was no significant difference in the all-cause mortality, AF-free survival, and PPM-free survival between PAC numbers 0 to 7 beats/day (Quartile 1) and PAC numbers 7 to 37 beats/day (Quartile 2). The impact of PAC numbers <37 in the incidence of mortality, occurrence of new-onset AF, and need for PPM implantation might be low or limited due to the period of follow-up. In our study, the cut-off value was relatively lower than in previous studies. One reason is that most previous studies used 12-lead ECG or 2-minute strip, which could not clearly identify PAC burdens. The other reason is that the follow-up period of our study was longer than that of most previous studies using 24-hour ECG monitoring, so that the impact of low PAC burdens could emerge.

PACs and the Need for Cardiac Pacing

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated the relationship between PACs and risk of PPM implantation. This study is the first to report that an elevated PAC burden is associated with an increment in the incidence of PPM implantation after adjusting for potential confounding factors. In the subgroup analysis, the presence of frequent PACs was significantly associated with PPM implantation for sick sinus syndrome involving long pause and tachy-brady syndrome, as well as high-degree atrioventricular block. However, the mechanism for the association between PACs and cardiac conduction system dysfunction was unclear. Frequent atrial stimulation might cause atrial substrate remodeling near the sinus nodal area, causing dysfunction of the sinus node.22–24 AF could cause profound electrophysiological and structural remodeling of the atrioventricular node.7 These findings suggest that frequent PACs might mimic, at least in part, the pathophysiology of AF in the human heart and contribute to sinus and, possibly, atrioventricular node dysfunction.7,22–24

Patients with symptomatic PACs were more likely to receive β-blockers for symptom control. β-blockade could slow the heart rate and disturb cardiac conduction, thereby increasing the risk of sick sinus syndrome and heart block. A complex and cyclic relationship could exist between frequent PACs and cardiac conduction disturbance. For example, isolated atrioventricular block has been associated with the development of ectopic beats and tachyarrhythmia,25,26 whereas symptomatic sinus node dysfunction has been associated with abnormal atrioventricular node conduction.27 This crosstalk could potentially explain the deterioration of cardiac conduction in patients with frequent PACs.

PACS: A Marker of the General Conduction?

In our study, patients with frequent PACs were generally older. Cardiac arrhythmia and cardiac rhythm disturbances are frequently found in elderly people as a result of degenerative changes and/or comorbidities. Although we tried to show significant differences in prevalence for most comorbidities, our study could be underpowered to disclose all possible comorbidities. Frequent PACs might be a marker of an underdiagnosed physical condition that can lead to adverse outcomes, including mortality, hospitalization, and PPM implantation. Furthermore, in the elderly, arrhythmias are a significant cause of falls, physical disability, and frequent hospital visits, which would make subsequent hospitalization, sinus and atrioventricular node dysfunction, and AF episodes easier to detect than in younger (healthier) subjects.

Clinical Perspective

The clinical significances of this study are the following: (1) excessive numbers of PACs may increase the risk of atrial fibrillation, hospitalization, and mortality; (2) frequent PACs might contribute to subclinical heart disease, and could lead to the progression of remodeling. Our study can help increase clinicians’ awareness that a more intense follow-up may allow early detection of AF or subclinical heart disease. Advanced treatment of underlying disease could interrupt the progress of cardiac remodeling.

Study Limitations

This study had some limitations. Regarding the baseline characteristics, the patient group with a PAC burden >76 beats per day was older, predominantly male, and had higher incidence rates of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and previous myocardial infarction compared to the group with a PAC burden ≤76 beats per day. This selection bias might still exist even after the Cox regression hazard model and propensity-matched score adjustment for extensive risk factors were applied. For example, there was a significant difference in age between patients on either side of the PAC cut-off; therefore, propensity-matched multivariable logistic regression was used to control for confounders. The resulting HR still indicated a significantly higher mortality risk in the frequent PAC group. However, it is not clear whether multivariate analysis or propensity-matching methods could reasonably correct for selection bias from the start. Further prospective study conducted in the general population without clinical symptoms might give us more information.

Second, it is possible that we overestimated the impact of PACs on dysfunction of the sinus and atrioventricular nodes. The association between AF and sinus node dysfunction is well known.24 Our observation might be an upstream manifestation, with symptoms of palpitation or syncope/presyncope, one of the indications for Holter monitoring in our study group. These symptoms might be present during the early stage of PACs.

Third, our study population was not representative of the general population. The study population had a higher CV risk and was referred for cardiac symptoms in the initial setting. Holter indication may stratify PAC frequency or study outcomes. Further prospective study might be necessary before applying these results in a clinical setting.

Fourth, the PAC burden may be higher in the setting of organic diseases of the sinus or atrioventricular node. Frequent PACs might be a marker of an underdiagnosed physical condition that can lead to sinus and atrioventricular node dysfunction.

Furthermore, the follow-up was not balanced between all the patients, and it was far more likely for an event to be observed in a higher risk patient than a lower risk one. Although the results of the Cox regression hazards model were compatible with the propensity-matching methods, we could not eliminate the possibility of follow-up bias in the study population.

Conclusions

The results of this 10-year follow-up study demonstrated that the burden of PACs might be associated with higher risks of mortality, CV hospitalization, new-onset AF, and PPM implantation. These associations were independent of other known clinical risk factors.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants NSC 100-2314-B-075-046-MY3, 101-2314-B-010-057-MY3, 101-2314-B-075-056-MY3, Taipei Veterans General Hospital grant V102C-054, V102E7-002, VGHUST102-G1-1-1, Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation CI-102-18, and International Center of Excellence in Advanced Bio-engineering sponsored by the Taiwan National Science CouncilI-RiCE Program under Grant Number NSC 99-2911-I-009-101; NSC 99-2314-B-075-032, NSC 99-2314-B-016-034-MY3.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting Information

Table S1.Baseline characteristics of propensity-matched patient.

Table S2. Ten-year event rates in propensity-matched patients with and without premature atrial complex more than 76 beats per day.

References

- Binici Z, Intzilakis T, Nielsen OW, Kober L, Sajadieh A. Excessive supraventricular ectopic activity and increased risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke. Circulation. 2010;121:1904–1911. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.874982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conen D, Adam M, Roche F, Barthelemy JC, Felber Dietrich D, Imboden M, Kunzli N, von Eckardstein A, Regenass S, Hornemann T, Rochat T, Gaspoz JM, Probst-Hensch N, Carballo D. Premature atrial contractions in the general population: frequency and risk factors. Circulation. 2012;126:2302–2308. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.112300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong BH, Pong V, Lam KF, Liu S, Zuo ML, Lau YF, Lau CP, Tse HF, Siu CW. Frequent premature atrial complexes predict new occurrence of atrial fibrillation and adverse cardiovascular events. Europace. 2012;14:942–947. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, Israel CW, Van Gelder IC, Capucci A, Lau CP, Fain E, Yang S, Bailleul C, Morillo CA, Carlson M, Themeles E, Kaufman ES, Hohnloser SH Investigators A. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:120–129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofoma U, He F, Shaffer ML, Naccarelli GV, Liao D. Premature cardiac contractions and risk of incident ischemic stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e002519. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.002519. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.002519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra RC, Wyndham C, Amat YL, Denes P, Wu D, Rosen KM. Sinus nodal responses to atrial extrastimuli in patients without apparent sinus node disease. Am J Cardiol. 1975;36:445–452. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(75)90892-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Mazgalev TN. Atrioventricular node functional remodeling induced by atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1419–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocini M, Sanders P, Deisenhofer I, Jais P, Hsu LF, Scavee C, Weerasoriya R, Raybaud F, Macle L, Shah DC, Garrigue S, Le Metayer P, Clementy J, Haissaguerre M. Reverse remodeling of sinus node function after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with prolonged sinus pauses. Circulation. 2003;108:1172–1175. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000090685.13169.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KL, Liu CJ, Chao TF, Huang CM, Wu CH, Chen SJ, Chen TJ, Lin SJ, Chiang CE. Statins, risk of diabetes, and implications on outcomes in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao TF, Liu CJ, Chen SJ, Wang KL, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Lo LW, Hu YF, Tuan TC, Chen TJ, Tsao HM, Chen SA. Hyperuricemia and the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation—could it refine clinical risk stratification in AF? Int J Cardiol. 2014;170:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao TF, Hung CL, Chen SJ, Wang KL, Chen TJ, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Lo LW, Hu YF, Tuan TC, Chen SA. The association between hyperuricemia, left atrial size and new-onset atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:4027–4032. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CY, Chen CH, Li CY, Lai ML. Validating the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke in a national health insurance claims database. J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;114:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu TH, Lee MC, Chou MC. Accuracy of cause-of-death coding in Taiwan: types of miscoding and effects on mortality statistics. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:336–343. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Causal effects in clinical and epidemiological studies via potential outcomes: concepts and analytical approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheriyath P, He F, Peters I, Li X, Alagona P, Jr, Wu C, Pu M, Cascio WE, Liao D. Relation of atrial and/or ventricular premature complexes on a two-minute rhythm strip to the risk of sudden cardiac death (the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities [ARIC] study) Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakoshi N, Xu D, Sairenchi T, Igarashi M, Irie F, Tomizawa T, Tada H, Sekiguchi Y, Yamagishi K, Iso H, Yamaguchi I, Ota H, Aonuma K. Prognostic impact of supraventricular premature complexes in community-based health checkups: the Ibaraki Prefectural Health Study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:170–178. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewland TA, Vittinghoff E, Mandyam MC, Heckbert SR, Siscovick DS, Stein PK, Psaty BM, Sotoodehnia N, Gottdiener JS, Marcus GM. Atrial ectopy as a predictor of incident atrial fibrillation: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:721–728. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-11-201312030-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegel KM, Shipley MJ, Rose G. Risk of stroke in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation. Lancet. 1987;1:526–529. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, McNamara PM. Coronary heart disease and atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1983;106:389–396. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacchia CF, Akoum NW, Wasmund S, Hamdan MH. Atrial bigeminy results in decreased left ventricular function: an insight into the mechanism of PVC-induced cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:1232–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. Am J Med. 1995;98:476–484. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvan A, Wylie K, Zipes DP. Pacing-induced chronic atrial fibrillation impairs sinus node function in dogs. Electrophysiological remodeling. Circulation. 1996;94:2953–2960. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fareh S, Villemaire C, Nattel S. Importance of refractoriness heterogeneity in the enhanced vulnerability to atrial fibrillation induction caused by tachycardia-induced atrial electrical remodeling. Circulation. 1998;98:2202–2209. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.20.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HY, Lin YJ, Lo LW, Chang SL, Hu YF, Li CH, Chao TF, Yin WH, Chen SA. Sinus node dysfunction in atrial fibrillation patients: the evidence of regional atrial substrate remodelling. Europace. 2013;15:205–211. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Murakawa Y, Ajiki K, Omata M. Incidence of induced atrial fibrillation/flutter in complete atrioventricular block. A concept of ‘atrial-malfunctioning’ atrio-hisian block. Circulation. 1997;95:650–654. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.3.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BA, Arce CM, Hlatky MA, Turakhia M, Setoguchi S, Winkelmayer WC. Trends in the incidence of atrial fibrillation in older patients initiating dialysis in the United States. Circulation. 2012;126:2293–2301. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.099606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen KM, Loeb HS, Sinno MZ, Rahimtoola SH, Gunnar RM. Cardiac conduction in patients with symptomatic sinus node disease. Circulation. 1971;43:836–844. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.6.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.Baseline characteristics of propensity-matched patient.

Table S2. Ten-year event rates in propensity-matched patients with and without premature atrial complex more than 76 beats per day.