Abstract

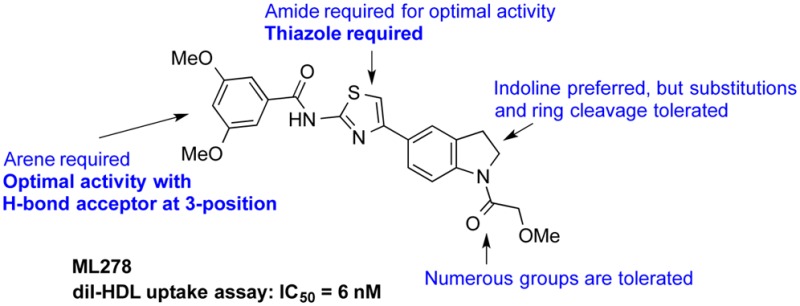

A potent class of indolinyl-thiazole based inhibitors of cellular lipid uptake mediated by scavenger receptor, class B, type I (SR-BI) was identified via a high-throughput screen of the National Institutes of Health Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (NIH MLSMR) in an assay measuring the uptake of the fluorescent lipid DiI from HDL particles. This class of compounds is represented by ML278 (17–11), a potent (average IC50 = 6 nM) and reversible inhibitor of lipid uptake via SR-BI. ML278 is a plasma-stable, noncytotoxic probe that exhibits moderate metabolic stability, thus displaying improved properties for in vitro and in vivo studies. Strikingly, ML278 and previously described inhibitors of lipid transport share the property of increasing the binding of HDL to SR-BI, rather than blocking it, suggesting there may be similarities in their mechanisms of action.

Keywords: ML278, SR-BI inhibitor, HDL receptor, reverse cholesterol transport, indoline, thiazole, HTS, MLP, HCV

The inverse correlation between human plasma HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) levels and risk for adverse events from atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD)1,2 has generated considerable interest in developing novel therapies that increase HDL-C levels by several different mechanisms,3 most prominently by cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibition.4 Despite massive investments in the clinical study of these inhibitors, the strategy of decreasing CAD risk by artificially boosting HDL-C levels has yet to be validated, and our understanding of lipid trafficking and regulation remains incomplete. New pharmacologic tools that selectively modulate HDL-C via different targets would be valuable for in vitro mechanistic studies and in vivo functional analyses. Here we attempted to identify compounds that can modulate the actions of scavenger receptor, class B type I (SR-BI),5 a mammalian high density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor that binds HDL particles on the cell surface and mediates transport of unesterified cholesterol (UC) or cholesteryl esters (CE). Unlike LDL-receptor mediated uptake of lipids, this process is independent of endocytosis.5,6 In vivo, the structure and composition of plasma HDL and the metabolic fates of its cholesterol are controlled by SR-BI.7 In fact, SR-BI has important influences on the gastrointestinal, endocrine, and reproductive systems, as well as development, inflammation/host defense, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and cardiovascular physiology.7−13

Thus, SR-BI is an interesting drug target, particularly for compounds that may modulate cholesterol levels or inhibit HCV infection. However, despite several informative, mechanistic studies14−16 the precise details of HDL recognition by SR-BI and consequent lipid uptake and efflux remain unclear; new chemical probes may help further our understanding of these processes.17

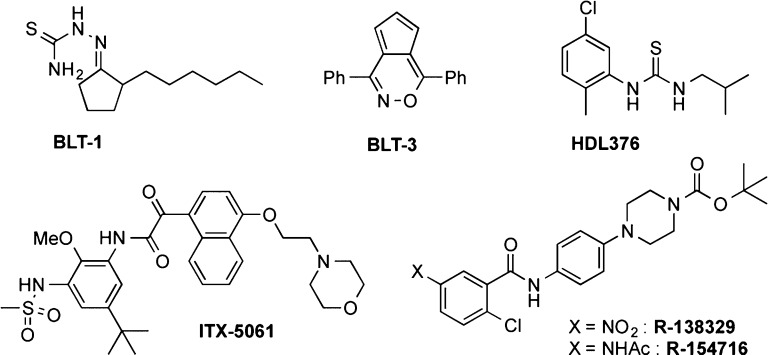

We and others have previously discovered small molecule inhibitors of SR-BI (some examples in Figure 1), which have subsequently proven to be valuable tools in the study of the activities of SR-BI in vitro and in vivo, including lipid transport and lipoprotein metabolism (BLTs,18 HDL376,19,20 R-13832921) and HCV infection (ITX-506122,23). Unfortunately, the reported disadvantages of these tool compounds limit their utility, including toxicity (BLT-1), weak potency (BLT-3, BLT-4), specificity (mitogen-activated protein kinase activity; ITX-5061), and potential safety issues for humans (HDL376). ITX-5061 also recently showed disappointing results in a Phase 1b clinical trial.24 It would be valuable to identify additional potent SR-BI chemical modulators that lack detrimental side effects25 and that might selectively modulate lipid uptake or efflux.

Figure 1.

Some reported inhibitors of SR-BI.

Under the auspices of the NIH’s Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network (MLPCN), we used a high-throughput screening approach to identify potent SR-BI modulators with low toxicities and favorable physicochemical properties that may be useful as in vitro and in vivo probes of SR-BI mechanism and function, and that might also be promising lead compounds for drug discovery. The screen involved measuring the effects of cellular uptake of the fluorescent lipid 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI) from HDL particles into CHO cells overexpressing mouse SR-BI (ldlA[mSR-BI]).26 An initial probe report is available,27 and assay data may be found in the PubChem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, AID 488952).

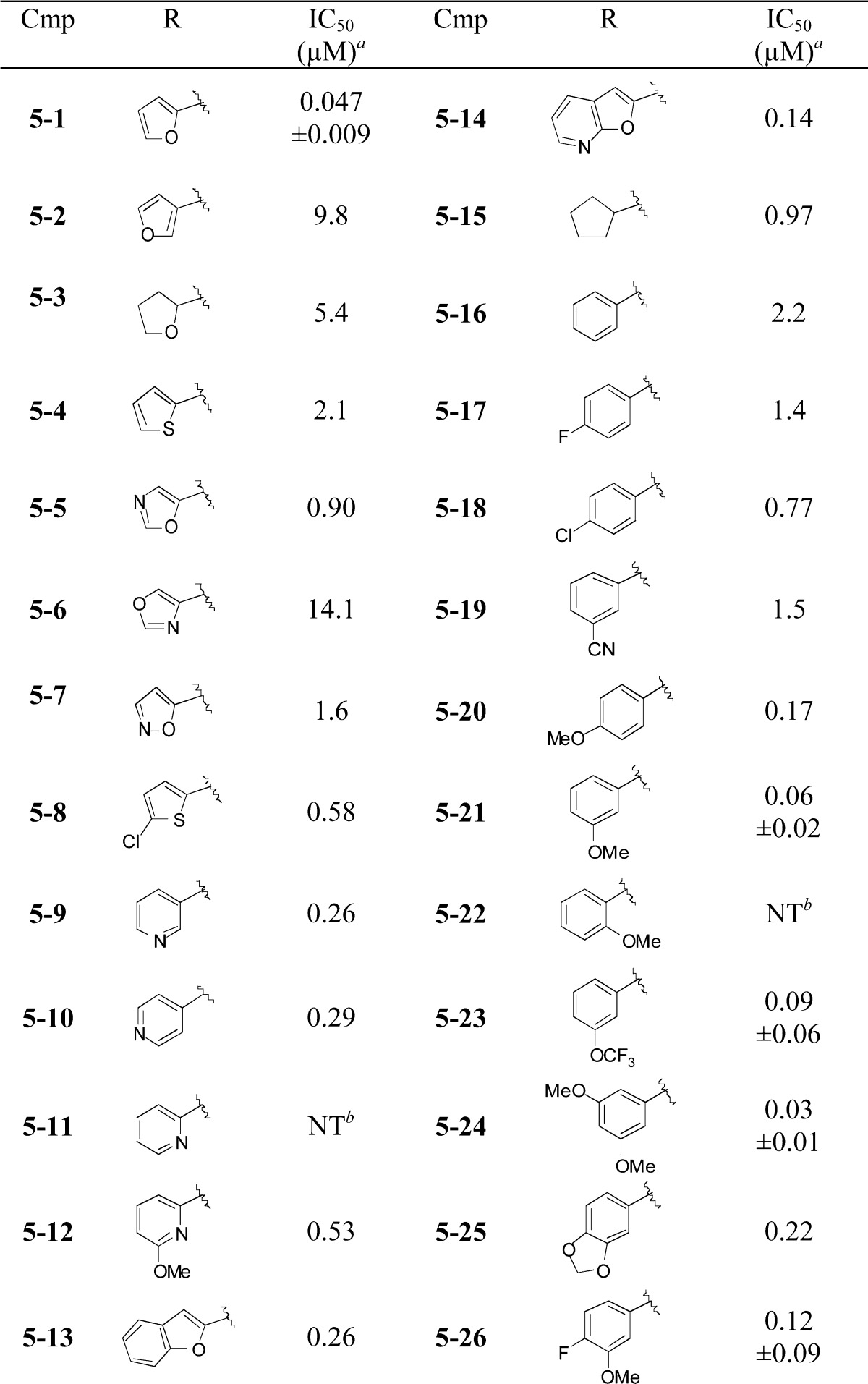

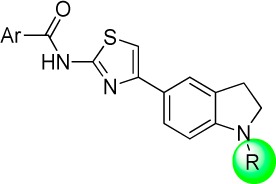

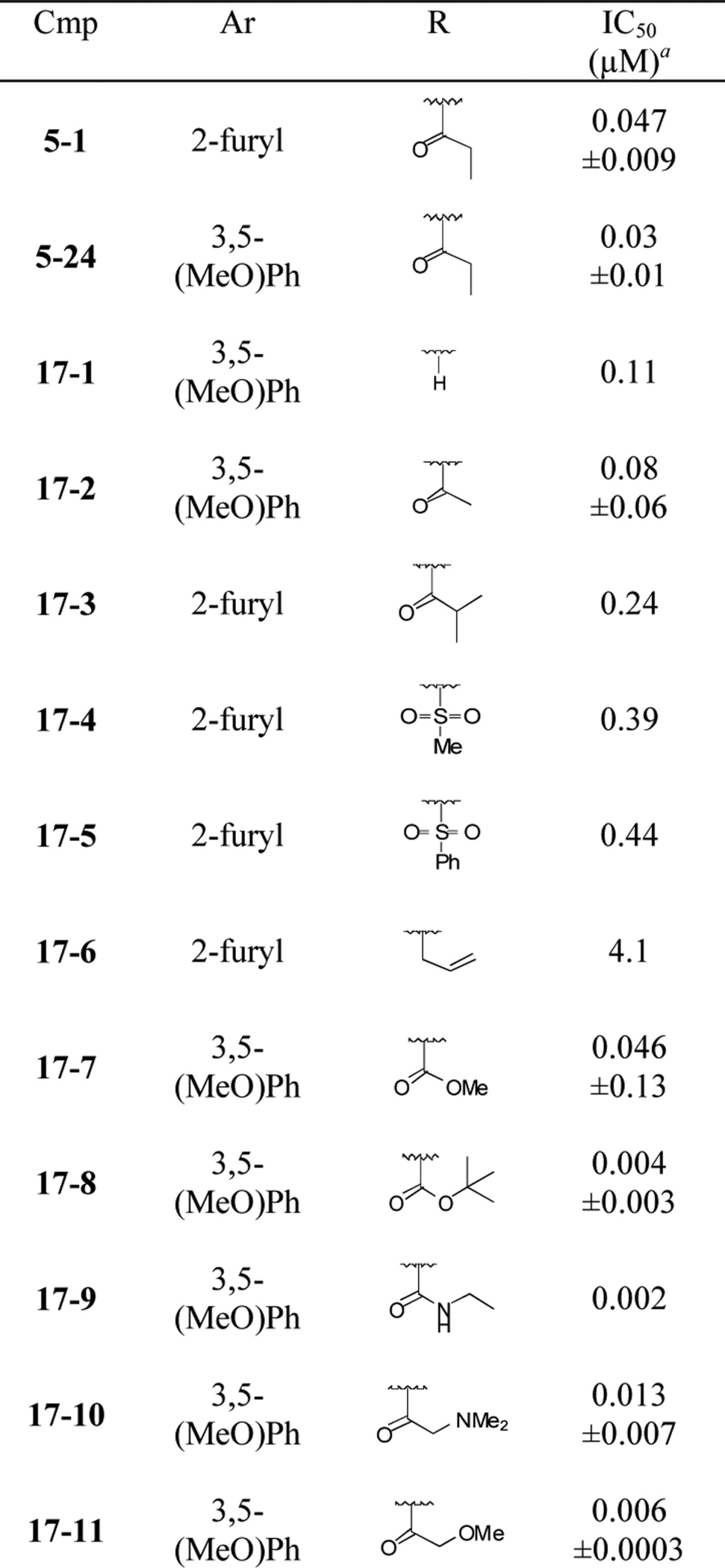

Of the 319,533 compounds tested in duplicate at 12.5 μM, 3046 compounds (0.96%) reduced cellular fluorescence with inhibition of ≥70% of that of 1 μM BLT-1, the positive control and one of the most potent inhibitors readily available. Hit compounds that were on plates with Z′ < 0.3 or that were active in 10% or more of the HTS assays listed in PubChem were eliminated as either unreliable or too nonspecific. From the primary screen, a variety of scaffolds was verified to inhibit DiI uptake with IC50s of <1 μM. Here, 127 out of 186 of the selected hits that showed dose-dependent inhibition of DiI uptake were rejected for further study because secondary screening established that they quench the intrinsic fluorescence of DiI in DiI-HDL. We describe here our structure–activity analysis of one of the most potent scaffolds, represented by the commercially available indolinyl-thiazole 5–1, with an IC50 of 0.047 μM (Table 1). This scaffold was chosen for further analysis in part for its modularity and synthetic tractability and for its lack of measurable toxicity after incubation with CHO cells for 24 h. Furthermore, 5–1 appeared to lack nonselective behavior based on data in PubChem.28

Table 1. Amide Analogues.

Average of at least two measurements in DiI uptake assay; ±standard error of mean when n > 2.

Insoluble in DMSO. NT = not tested.

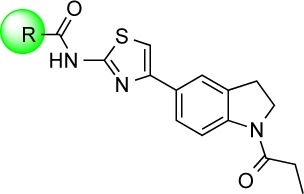

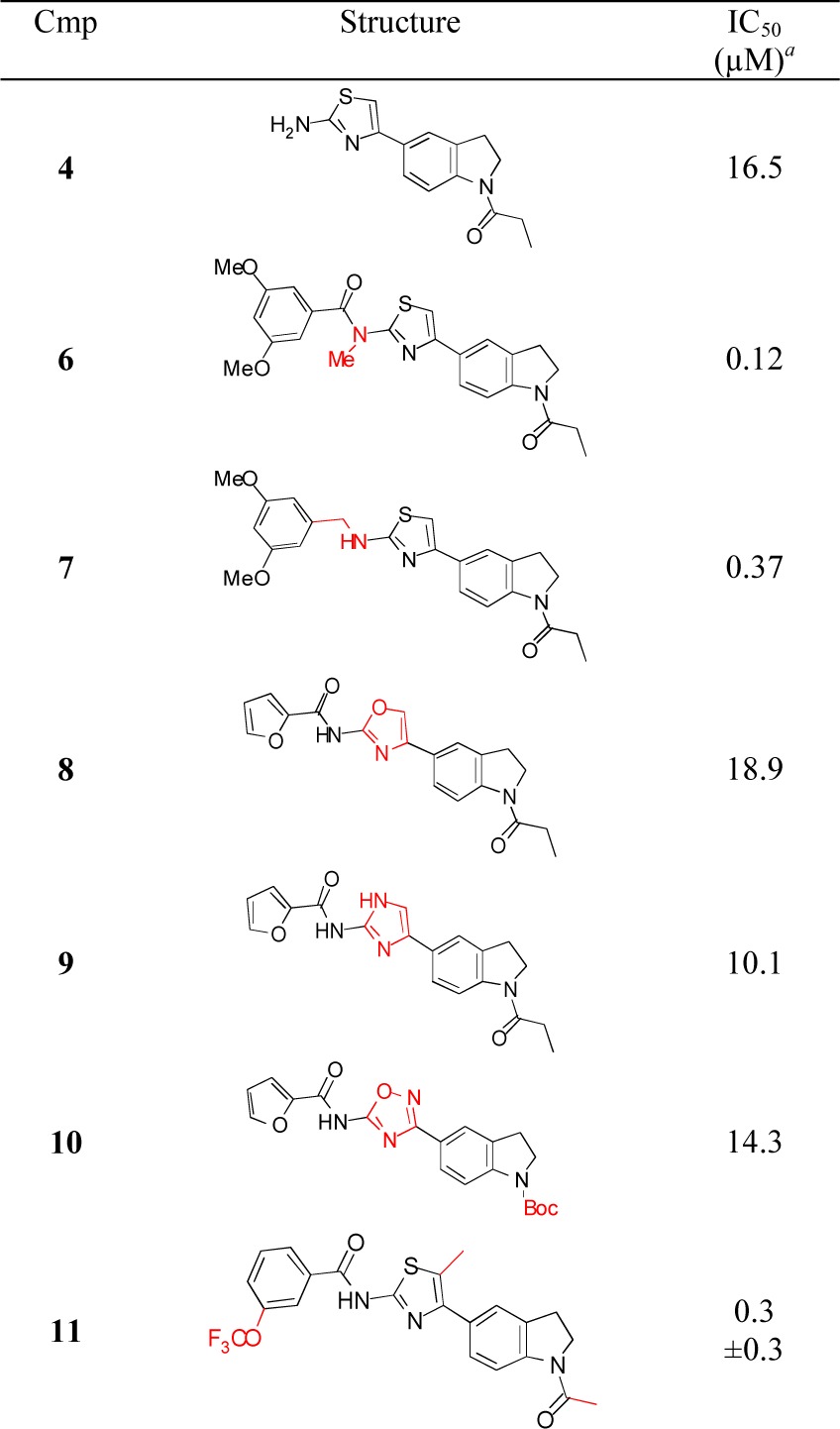

We explored structure–activity relationships (SAR) of the scaffold by first varying the N-substituent of the aminothiazole. The indolinyl-aminothiazole core of 5–1 was prepared via a simple 3-step sequence (Scheme 1). Indoline 1 was acylated with propionyl chloride, and the resulting amide 2 was subjected to Friedel–Crafts acylation with chloroacetyl chloride. The chloroketone 3 was condensed with thiourea to provide the desired aminothiazole 4. The poor solubility and nucleophilicity of 4 required heating with the acid chloride coupling partners for optimal preparation of a series of amide derivatives of 5 (Table 1). Caution should be taken with the interpretation of the SAR analysis in this series, as the compounds nearly all have measured solubility in PBS of <1 μM. Despite these issues, the top compounds in this report showed reproducible inhibition and were very potent, providing low nanomolar IC50 values.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Amide Analogues.

A number of heterocyclic analogues (Table 1, 5–2–5–14) were examined to find a replacement for the furan of 5–1, which is a potential toxicophore.29 None of these compounds provided a level of inhibition comparable to 5–1. A number of aliphatic (5–15) and aromatic (5–16–5–26) analogues were prepared, and analogues with a 3-alkoxybenzene substituent (5–21, 5–23, 5–24, 5–26) provided high levels of inhibition with IC50s in the range of 30 to 120 nM.

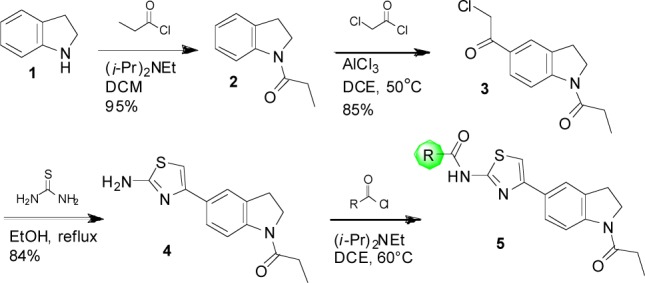

We next modified the central heterocyclic ring, as well as the adjacent amide functionality (Table 2). The parent aminothiazole 4 showed poor activity. N-Methylation of 5–24 (6) or reduction of the amide (7) gave compounds with attenuated activity. A number of heterocyclic replacements for the central thiazole were prepared, including oxazole 8, imidazole 9, and 1,2,4-oxadiazole 10. The activities sharply decreased in all cases. A 5-methyl group was tolerated on the thiazole (11), which may decrease the potential of thiazole ring oxidation by CYP enzymes to give toxic metabolites.30 Compound 11 also demonstrates that a trifluoromethoxy group could be a potential replacement of the 3-methoxy substituent.

Table 2. Functional Group Modifications and Central Ring SAR.

Average of at least two measurements in DiI uptake assay; ±standard error of mean when n > 2.

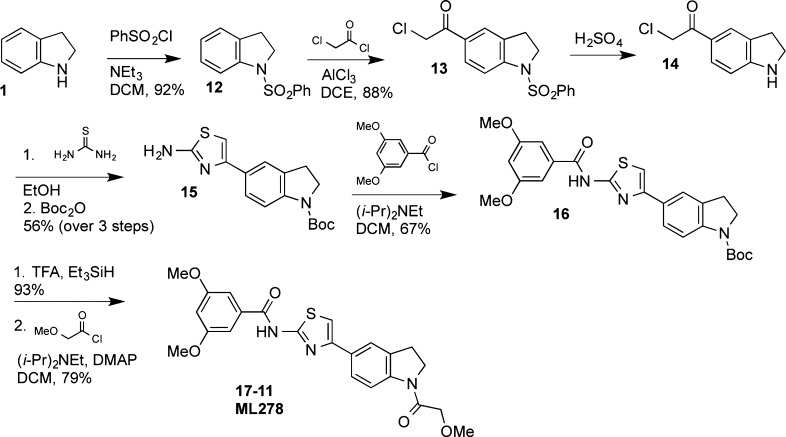

SAR studies were continued by modifying the indoline N-substituent; a representative synthesis is provided in Scheme 2. Protection of the indoline nitrogen with a phenylsulfonyl group provided an intermediate (12) that underwent Friedel–Crafts acylation with chloroacetyl chloride to yield ketone 13 in high yield. The sulfonamide could be hydrolyzed in the presence of the chloroketone by heating in sulfuric acid. The resulting indoline 14 was subsequently condensed with thiourea to generate a 2-aminothiazole, which reacted with Boc2O exclusively at the indoline nitrogen to generate carbamate 15. The free amine of 15 was acylated with the desired acid chlorides, the Boc group was removed with TFA, and the indoline nitrogen was acylated to provide compounds 17 (Table 3).

Scheme 2. Representative Synthesis of Analogues with Alternative Indoline N-Substituents.

Table 3. Modifications to Indolinyl Amide.

Average of at least two measurements in DiI uptake assay; ±standard error of mean when n > 2.

Removal of (17–1) or shortening (17–2) the indolinyl acyl group of 5–24 did not improve activity; whereas, the addition of a methyl group to the ethyl chain of compound 5–1 (17–3) decreased potency. The sulfonamides 17–4 and 17–5 showed an approximately 10-fold drop in potency relative to 5–24, and the N-allyl indoline 17–6 showed only weak inhibition. More positive results were obtained with compounds 17–7 to 17–11. Both smaller and bulkier substituents were well tolerated with compounds possessing the western 3,5-dimethoxybenzene moiety. The N-Boc compound 17–8 showed excellent potency in the DiI-uptake assay (4 nM), as did the urea 17–9 (2 nM) and the methoxyacetamide 17–11 (6 nM).

Modifications to the indoline ring itself were also examined. A selection of our results is provided in the Supporting Information (Table S1). A range of anilines and oxindoles showed good to excellent potencies, though none were superior to the top indoline compounds, and they also suffered from very low solubilities (<1 μM).

Several of our more promising compounds were profiled in secondary assays to gain insights into the mode of action and potential for further development of the indolinyl-thiazole compound class. None of the compounds showed any significant cytotoxicity after incubation with the ldlA[mSR-BI] cells for 24 h, and in fact compounds 6 (CC50 = 15 μM) and 17–10 (CC50 = 20 μM) were the only ones with measurable cytotoxicities.31 Solubility is an issue with this series of compounds, as all of the compounds tested with low nanomolar IC50s have solubilities of <1 μM. The methoxyacetamide 17–11 showed excellent potency (IC50 = 6 nM), measurable solubility (0.57 μM), and excellent stability in human plasma (>99% remaining after 5 h, with 94% plasma protein-bound). Compound 17–11 was nominated as a probe (ML278) as part of the NIH Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network (MLPCN) initiative.

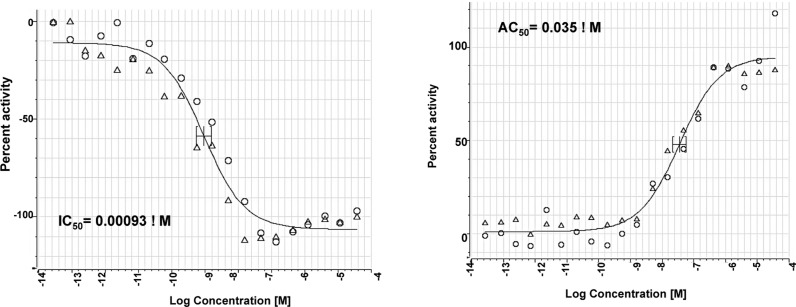

Additional mechanistic studies with ML278 were performed to obtain details on its mode of action. First, in experiments where cells were pretreated with ML278 for 2 h, washed extensively with PBS, and then incubated with DiI-HDL, sharply reduced levels of inhibition were observed. This demonstrates that the inhibitory action of ML278 is reversible. In addition to inhibiting the selective uptake of the synthetic lipid tracer DiI from HDL into ldlA[m-SR-BI] cells (Table 3 and Figure 2, left frame), ML278 inhibited uptake of the physiological relevant [3H]labeled cholesteryl oleate ester ([3H]CE) from [3H]CE-HDL (calculated IC50 = 7 nM, Supporting Information Figure S1). Its potency in these assays is far greater than the clinical compound ITX-5061 (IC50 = 0.94 μM, see comparison in Supporting Information Table S2). We also showed that, as was the case for BLT-1 and other SR-BI inhibitors, ML278 enhanced the binding of fluorescent Alexa448-HDL to SR-BI (EC50 = 0.035 μM) (Figure 2, right frame). Thus, ML278 joins a growing list of small molecules that inhibit lipid transport mediated by SR-BI yet increase the binding of HDL to SR-BI.18

Figure 2.

DiI-HDL uptake assay with ML278 (left); Alexa488-HDL binding assay with ML278 (right).

The potential utility of ML278 as a probe for in vivo studies was investigated by measuring its metabolic stability in the presence of liver microsomes (Supporting Information Table S2). The compound shows moderate stability, with 75% remaining after 1 h incubation with CD-1 mouse liver microsomes and 48% remaining with human liver microsomes. Additionally, competitive binding studies were performed with a panel of 67 different receptors and secondary targets (Eurofins Panlabs). At a concentration of 10 μM, 11 targets were inhibited by 20% or more, with the highest level of inhibition observed with the Adenosine A3 receptor (43% inhibition).

In summary, potent inhibitors of SR-BI-mediated lipid uptake were discovered as part of the NIH Molecular Libraries Program. Profiling of several top compounds led to the nomination of the indolinyl-thiazole 17–11 (ML278) as a probe compound. SAR studies demonstrated that the thiazole of ML278 was required for activity, flanked by a benzamide, optimally with a 3-methoxy substituent. ML278 shows superior potency in the uptake of the synthetic lipid tracer DiI, as well as [3H]CE, compared to the prior art compounds BLT-1 and ITX-5061. ML278 also shows no cytotoxicity, has no significant chemical liabilities, shows reversible inhibition, and appears to act selectively at SR-BI. Additionally, it has excellent plasma stability and moderate metabolic stability. ML278 is expected be a valuable tool compound for further in vitro and in vivo studies involving SR-BI.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Johnston, Carrie Mosher, Travis Anthoine, and Mike Lewandowski for analytical chemistry support.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- Boc

tert-butoxycarbonyl

- CC50

half-maximal cytotoxic concentration

- CE

cholesteryl ester

- CETP

cholesteryl ester transfer protein

- CHO

Chinese Hamster Ovary

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DCE

1,2-dichloroethane

- DMAP

4-(N,N-dimethylamino)-pyridine

- DiI

1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate

- EC50

half-maximal effective concentration

- EtOH

ethanol

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

high density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HTS

high-throughput screen

- IC50

half-maximal inhibitory concentration

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MLP

Molecular Libraries Program

- MLPCN

Molecular Libraries Probe Production Centers Network

- MLSMR

Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NO

nitric oxide

- NT

not tested

- PPR

pattern recognition receptor

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- SR-BI

scavenger receptor class B, type I

- TFA

2,2,2-trifluoroacetic acid

- Z′,Z′-factor

a measure of assay quality calculated from the variability of positive and negative controls32

Supporting Information Available

Additional SAR data; preparation and characterization of 17–11 (ML278); probe comparison table; representative dose–response curves of ML278 and ITX-5061 in [3H]CE uptake assay; compound profiling and assay protocols; off-target screening data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Funding for this work was provided in part by the NIH-MLPCN program (1 U54 HG005032-1 awarded to S.L.S.) and NIH grants HL052212 and HL066105 to M.K.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): A patent application is pending for compounds described in this manuscript.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Boden W. E. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol as an independent risk factor in cardiovascular disease: assessing the data from Framingham to the Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial. Am. J. Cardiol. 2000, 86, 19L–22L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight B. F.; et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet 2012, 380, 572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deGoma E. M.; Rader D. J. Novel HDL-directed pharmacotherapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2011, 8, 266–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See for example:Ranalletta M.; et al. Biochemical characterization of cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 2739–2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acton S.; Rigotti A.; Landschulz K. T.; Xu S.; Hobbs H. H.; Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science 1996, 271, 518–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. S.; Goldstein J. L. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science 1986, 232, 34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti A.; Miettinen H. E.; Krieger M. The role of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI in the lipid metabolism of endocrine and other tissues. Endocr. Rev. 2003, 24, 357–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti J.; Medina-Echeverz J.; Berraondo P. Scavenger receptor type B, class I: A promising immunotherapy target. Immunotherapy 2011, 3, 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L.; Song Z.; Li M.; Wu Q.; Wang D.; Feng H.; Bernard P.; Daugherty A.; Huang B.; Li X. A. Scavenger receptor BI protects against septic death through its role in modulating inflammatory response. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 19826–19834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P.; Liu X.; Treml L. S.; Cancro M. P.; Freedman B. D. Mechanism and regulatory function of CpG signaling via scavenger receptor B1 in primary B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 22878–22887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisset C.; Callens N.; Blanchard E.; Op De Beeck A.; Dubuisson J.; Vu-Dac N. High density lipoproteins facilitate hepatitis C virus entry through the scavenger receptor class B type I. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 7793–7799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanese M. T.; Graziani R.; von Hahn T.; Moreau M.; Huby T.; Paonessa G.; Santini C.; Luzzago A.; Rice C. M.; Cortese R.; Vitelli A.; Nicosia A. High-avidity monoclonal antibodies against the human scavenger class B type I receptor efficiently block hepatitis C virus infection in the presence of high-density lipoprotein. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 8063–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanese M. T.; Ansuini H.; Graziani R.; Huby T.; Moreau M.; Ball J. K.; Paonessa G.; Rice C. M.; Cortese R.; Vitelli A.; Nicosia A. Role of scavenger receptor class B type I in hepatitis C virus entry: kinetics and molecular determinants. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papale G. A.; Hanson P. J.; Sahoo D. Extracellular disulfide bonds support scavenger receptor Class B Type I-mediated cholesterol transport. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 6245–6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidukov L.; Nager A. R.; Xu S.; Penman M.; Krieger M. Glycine dimerization motif in the N-terminal transmembrane domain of the high density lipoprotein receptor SR-B1 required for normal receptor oligomerization and lipid transport. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 18452–18464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M.; Lau T. Y.; Carr S. A.; Krieger M. Contributions of a disulfide bond and a reduced cysteine side chain to the intrinsic activity of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 10044–10055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- During the preparation of this manuscript, the x-ray crystal structure of LIMP-2 was determined, a pattern-recognition recognition receptor in the same CD36 superfamily as SR-BI:Neculai D.; Schwake M.; Ravichandran M.; Zunke F.; Collins R. F.; Peters J.; Neculai M.; Plumb J.; Loppnau P.; Pizarro J.-C.; Seitova A.; Trimble W. S.; Saftig P.; Grinstein S.; Dhe-Paganon S. Structure of LIMP-2 provides functional insights with implications for SR-BI and CD36. Nature 2013, 504, 172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieland T. J.; Penman M.; Dori L.; Krieger M.; Kirchhausen T. Discovery of chemical inhibitors of the selective transfer of lipids mediated by the HDL receptor SR-BI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 15422–15427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola G. M.; Damon R. E.; Eskesen B.; France D. S.; Paterniti J. R. Biological evaluation of 1-alkyl-3-phenylthioureas as orally active HDL-elevating agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieland T. J.; Shaw J. T.; Jaipuri F. A.; Maliga Z.; Duffner J. L.; Koehler A. N.; Krieger M. J. Lipid Res. 2007, 48, 1832–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa T.; Kitayama K.; Wakabayashi K.; Yamada M.; Uchiyama M.; Abe K.; Ubukata N.; Inaba T.; Oda T.; Amemiya Y. A novel compound, R-138329, increases plasma HDL cholesterol via inhibition of scavenger receptor BI- mediated selective lipid uptake. Atherosclerosis 2007, 194, 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syder A. J.; Lee H.; Zeisel M. B.; Grove J.; Soulier E.; Macdonald J.; Chow S.; Chang J.; Baumert T. F.; McKeating J. A.; McKelvy J.; Wong-Staal F. Small molecule scavenger receptor BI antagonists are potent HCV entry inhibitors. J. Hepatol. 2011, 54, 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H.; Wong-Staal F.; Lee H.; Syder A.; McKelvy J.; Schooley R. T.; Wyles D. L. Evaluation of ITX 5061, a scavenger receptor B1 antagonist: resistance selection and activity in combination with other hepatitis C virus antivirals. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 205, 656–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski M. S.; Kang M.; Matining R.; Wyles D.; Johnson V. A.; Morse G. D.; Amorosa V.; Bhattacharya D.; Coughlin K.; Wong-Staal F.; Glesby M. J. Safety and antiviral activity of the HCV entry inhibitor ITX5061 in treatment-naive HCV infected adults: A randomized, double-blind, Phase 1b study. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, 658–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Researchers at iTherX recently reported the structure of the HCV entry inhibitor ITX 4520, which is postulated to act as an inhibitor of SR-BI:Mittapalli G. K.; Zhao F.; Jackson A.; Gao H.; Lee H.; Chow S.; Pal Kaur M.; Nguyen N.; Zamboni R.; McKelvy J.; Wong-Staal F.; Macdonald J. E. Discovery of ITX 4520: A highly potent orally bioavailable hepatitis C virus entry inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4955–4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See Supporting Information for details.

- A Small Molecule Inhibitor of Scavenger Receptor BI-mediated Lipid Uptake—Probe. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK133420/ (accessed March 1, 2014). [PubMed]

- Compound 5–1 was active in five assays not involving SR-B1 out of 315 bioassays listed on December 10, 2011.

- Kalgutkar A. S.; Gardner I.; Obach R. S.; Shaffer C. L.; Callegari E.; Henne K. R.; Mutlib A. E.; Dalvie D. K.; Lee J. S.; Nakai Y.; O’Donnell J. P.; Boer J.; Harriman S. P. A comprehensive listing of bioactivation pathways of organic functional groups. Curr. Drug Metab. 2005, 6, 161–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepan A. F.; Walker D. P.; Bauman J.; Price D. A.; Baillie T. A.; Kalgutkar A. S.; Aleo M. D. Structural alert/reactive metabolite concept as applied in medicinal chemistry to mitigate the risk of idiosyncratic drug toxicity: a perspective based on the critical examination of trends in the top 200 drugs marketed in the United States. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 1345–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measured with a CellTiter-Glo assay (Promega) to determine cellular ATP levels.

- Zhang J.-H.; Chung T. D. Y.; Oldenburg K. R. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J. Biomol. Screening 1999, 4, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.