Abstract

Recently, multifunctional magnetic nanostructures have been found to have potential applications in biomedical and tissue engineering. Iron oxide nanoparticles are biocompatible and have distinctive magnetic properties that allow their use in vivo for drug delivery and hyperthermia, and as T2 contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Hydroxyapatite is used frequently due to its well-known biocompatibility, bioactivity, and lack of toxicity, so a combination of iron oxide and hydroxyapatite materials could be useful because hydroxyapatite has better bone-bonding ability. In this study, we prepared nanocomposites of iron oxide and hydroxyapatite and analyzed their physicochemical properties. The results suggest that these composites have superparamagnetic as well as biocompatible properties. This type of material architecture would be well suited for bone cancer therapy and other biomedical applications.

Keywords: iron oxide, hydroxyapatite, nanocomposite, superparamagnetic, bone cancer

Video abstract

Introduction

Cancer is the most dreaded disease, along with heart disease. Hyperthermia has attracted much interest in the treatment of cancer due to its advantages over chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Using hyperthermia, cancer cells are killed directly within a short period of time, whereas normal cells are unaffected.1 Magnetic hyperthermia is practiced by applying an external alternating magnetic field which in turn oscillates the magnetic moment of each particle, converting magnetic energy into heat. Superparamagnetic materials for magnetic hyperthermia are promising candidates for antitumor therapy because they have the capacity to destroy deep tumors and are controlled by an external magnetic field.2 Magnetic nanoparticles have attractive features that could be used effectively in nanomedicine. First, they have a controllable particle size (from a few nanometers to tens of nanometers). Second, they are magnetic, so can be manipulated by an external magnetic field. Third, they can be made to heat up, so can be used as hyperthermia agents, delivering large amounts of thermal energy to tumor cells and destroying them.3 If an iron oxide nanoparticle is below 45 nm in size, it is classified as superparamagnetic due to its line-type hysteresis loop iron oxide nanoparticles. The magnetite (Fe3O4) phase of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles has numerous in vivo applications, since it can respond to an external stimulus and heat up, and does not retain any magnetism after removal of the external magnetic field.4,5 Materials that are compatible with bone tissue are preferred for bone repair and hard tissue engineering.6 Hydroxyapatite (HAp) is widely used in this setting because of its exceptional biocompatibility, bioactivity, and osteoconductivity.7 A number of researchers have developed a variety of HAp-based magnetic materials for hyperthermia-based treatment of cancer.8–11

Murakami et al prepared a porous Fe3O4-HAp composite using a hydrothermal method. The composite holds 30% Fe3O4 in cages of rod-shaped HAp particles.8 Fe3O4 nanoparticles are prepared by a coprecipitation method, and a horizontal tumbling ball mill is used to mechanochemically synthesize submicron-sized HAp particles. According to Iwasaki et al9 this process promotes the dispersion of Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the HAp matrix. The magnetic Fe3O4 particles are coated with HAp by spray-drying. Donadel et al found that the spray-drying technique is an efficient and inexpensive method for creating spherical particles with a core/shell structure.10 Tampieri et al prepared iron-doped HAp endowed with superparamagnetic properties for hyperthermic application.11

These composites can be synthesized conventionally by mixing HAp nanopowder with Fe3O4 nanoparticles that are prepared separately. In this work, Fe3O4 nanoparticles were prepared by alkaline coprecipitation of ferric and ferrous chloride in aqueous solution. Nanocrystalline HAp was prepared using an optimized sol-gel method. Dry (zirconia ball) milling was used to blend the Fe3O4-HAp (0.70 w/w) nanoparticles. The Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles and their composite were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, thermogravimetric analysis, differential scanning calorimetry, vibrating sample magnetometry, and cytotoxicity tests. The method proposed in this paper is easy and cost-effective for preparing these nanocomposites. The synthesis and characterization of this biocompatible magnetic biomaterial is explained in detail, and the nanostructured Fe3O4-HAp composite is ideal for bone cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles

Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles were synthesized by the alkaline coprecipitation method. The molar ratio of Fe3+:Fe2+ chloride was maintained at 2:1. The prepared magnetite was black in color and the pH was maintained between 9 and 14.12 The overall reaction is written as:

| (1) |

Synthesis of HAp nanoparticles

The HAp nanoparticles were prepared by the wet chemical route method. First, 0.25 M phosphoric acid was prepared in distilled water. Ammonia (NH3) was added to this solution, with stirring to maintain the pH at 10. Next, a 1 M calcium nitrate tetrahydrate solution was prepared by dissolving in double-distilled water, which was then added slowly to the above phosphoric acid-ammonia solution. The solution was stirred vigorously for 1 hour and allowed to age at room temperature for 24 hours. The gel obtained after aging was dried at 80°C for 48 hours in a dry oven. The resulting mixture were washed repeatedly using distilled water. After washing, the powder was sintered for 2 hours at a temperature of 900°C.

Synthesis of Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposites

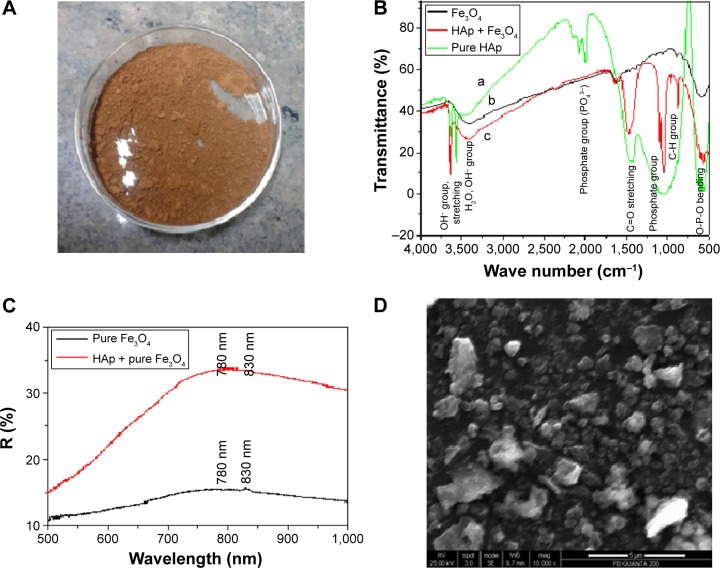

The Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposites were prepared using a wet-type ball mill (Figure 1A). The ratio of HAp to Fe3O4 nanoparticles was 1.5:1 (w/w). Ball milling was carried out for 5 hours using a zirconia bowl and ball at 300 rpm, with a ball to sample powder ratio of 10:1 (w/w).

Figure 1.

(A) Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles in powder form. (B) Fourier transform infrared spectra of HAp, Fe3O4, and Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles. (C) Diffuse reflectance spectra of magnetite and the composite. (D) Scanning electron micrograph of Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4, iron oxide; HAp, hydroxyapatite.

Characterization

Fourier transform infrared spectra were taken using an 8400S spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). KBr pellets were used, and the spectra were recorded in aqueous medium.

The morphology of the Fe3O4-HAp nanostructures was observed using a scanning electron microscope (ICON, Quanta 200 Mark II Environmental scanning electron microscope) with an acceleration voltage of 0.2–30 kV.

The thermal properties of the prepared nanocomposites were investigated using a thermal analyzer (STA 449 F3 Jupiter, Netzsch Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany) along with thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry in the temperature range of 28°C–1,100°C at a heating rate of 20°C per minute in a dry air atmosphere. Al2O3 was used as the reference material.

Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy was performed using a Specord 210 Plus (Analytik Jena, The Woodlands, TX, USA) between 190 and 1,100 nm at room temperature.

The superparamagnetic properties of the Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposites were studied using a 7410 vibrating sample magnetometer (Lake Shore, Westerville, OH, USA), in atmospheric air at room temperature.

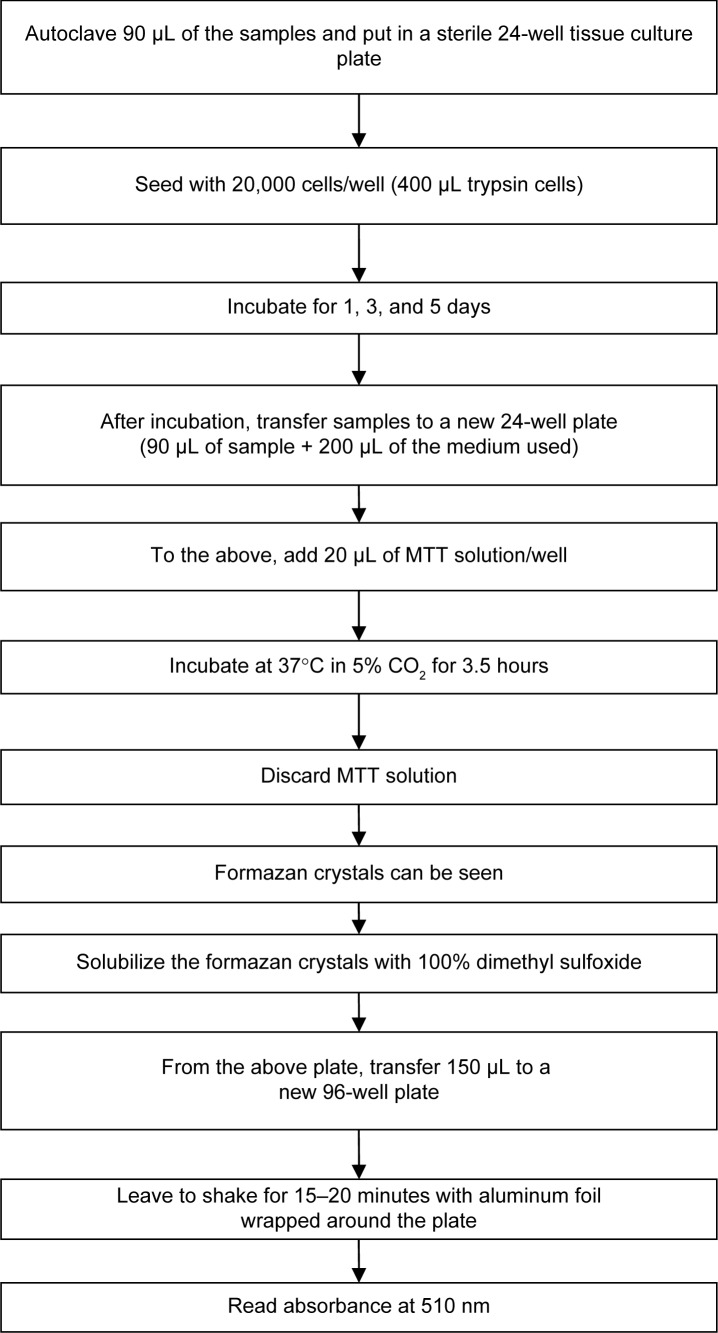

The cytotoxic effects of the Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposites were evaluated using MG63 cells. The MTT assay was performed according to the procedure shown in Figure 2. The formazan was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and the absorbance of the solution was quantified at 510 nm.

Figure 2.

Flow chart showing the MTT assay procedure.

Results and discussion

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

The Fourier transform infrared spectral assignments for pure Fe3O4, HAp, and the Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles are shown in Figure 1B and tabulated in Table 1. From these data, the functional groups of prepared samples confirms the presence of pure Fe3O4 and pure HAp. IN Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles, a slight variation in spectral assignments confirms the close interaction between Fe3O4 and HAp.

Table 1.

Fourier transform infrared spectral assignments of pure Fe3O4, HAp, and Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles

| S No | Wave number (cm−1)

|

Spectral assignments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | HAp | Fe3O4-HAp | ||

| 1 | – | 3,639 | 3,639 | OH− group, CaO |

| 2 | – | 3,561 | 3,570 | Stretching mode of OH− group |

| 3 | 3,420 | – | 3,420 | H2O, OH− group |

| 4 | – | 2,080 | – | Phosphate group (PO43−)/absorbed CO32− |

| 5 | – | 2,003 | – | Phosphate group (PO43−)/absorbed CO32− |

| 6 | – | – | 1,638 | O-H in-plane bending |

| 7 | 1,625 | – | – | (H-O-H) adsorbed water |

| 8 | – | 1,473 | 1,473 | CO32− |

| 9 | 1,383 | – | – | N-O nitro compounds |

| 10 | 1,151 | – | – | C-O |

| 11 | – | – | 1,091 | Phosphate group (PO43−) |

| 12 | 1,062 | – | – | C-O |

| 13 | – | 1,046 | 1,046 | Phosphate group (PO43−) |

| 14 | – | – | 960 | Phosphate group (PO43−) |

| 15 | 891 | – | – | C-H |

| 16 | – | – | 875 | C-H |

| 17 | 797 | – | – | C-H |

| 18 | – | – | 629 | C-Cl |

| 19 | – | – | 601 | O-P-O bending |

| 20 | 588 | – | – | Fe-O-Fe bond (Fe ions in tetrahedral and octahedral site) |

| 21 | – | 566 | 566 | O-P-O bending |

Abbreviations: Fe3O4, iron oxide; HAp, hydroxyapatite.

Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy

Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy provides the electron transition of pure and mixed samples. Figure 1C represents the diffuse reflectance spectra for pure Fe3O4 and Fe3O4-HAp. Pure Fe3O4 shows a wavelength (4Tl) transition in the range of 780–830 nm and an electron pair transition of 510 nm. This shows a higher position of the ligand-to-metal charge transfer transition and pair transition band of red Fe3O4.

Scanning electron microscopy

The micromorphology and texture of the Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposites are shown in Figure 1D. This scanning electron microscopic image shows that pure Fe3O4 has an irregular approximately spherical-like morphology with an average particle size in the range of 50–70 nm and that HAp has a particle size in the range of 30 – 40 nm. The aggregated Fe3O4-HAp clusters have a size range of 100–350 nm and both phases distributed uniformly, as shown in Figure 1D. The characteristic dark and light gray represents the Fe3O4 and HAp, respectively.

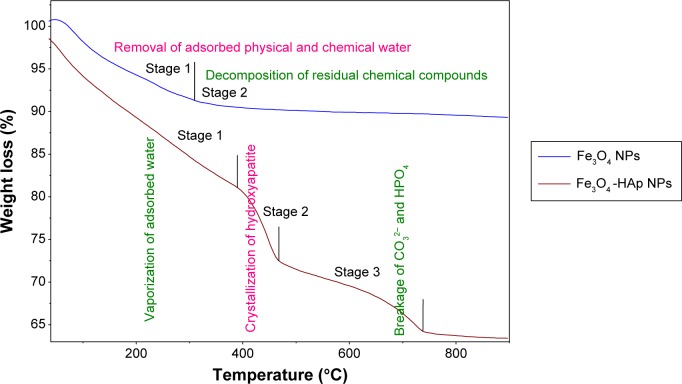

Thermogravimetric analysis

The Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles were studied by thermogravimetric analysis in a nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 20°C per minute. Figure 3 shows the thermogravimetric analysis curves, depicting the variations in residual mass of the samples with increasing temperature. The absolute weight loss from the uncoated Fe3O4 is nearly 17% for the whole temperature range due to removal of adsorbed physical and chemical water. Another 5% weight loss was seen from 160°C to 300°C, and this was associated with decomposition of residual chemical compounds. No significant weight loss was observed at higher temperatures. Thermogravimetric analysis of the Fe3O4-HAp powder showed weight loss up to a temperature of 800°C and thereafter weight remained constant.

Figure 3.

Weight loss from the Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4, iron oxide; HAp, hydroxyapatite; NPs, nanoparticles.

The first stage of weight loss is between 90°C and 390°C, which corresponds to dehydration of the precipitating complex and loss of physically adsorbed water molecules from the HAp powder. The weight loss in this region is 10%. Stage 1 corresponds to vaporization of adsorbed water on the surface of HAp, stage 2 is due to vaporization of the water and crystallization of HAp, and stage 3 is probably due to breakage of CO32− and HPO4 in HAp.

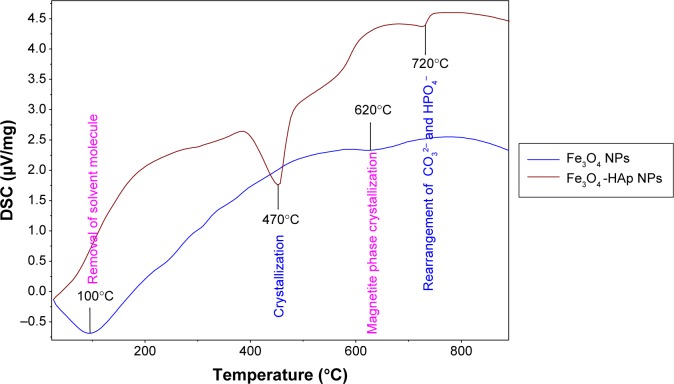

Differential scanning calorimetry

The differential scanning calorimetry analysis of Fe3O4 and the nanocomposite is shown in Figure 4. The pure Fe3O4 shows a strong endothermic peak approximately 100°C. This is due to removal of the solvent molecule (H2O). A slight endothermic transition approximately 620°C indicates crystallization of the magnetite phase. The differential scanning calorimetry results for the Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposite show a strong endothermic peak located in the range of 90°C–110°C. Two exothermic peaks were identified at 470°C and 720°C. The first one could be due to crystallization of the powder, given that this temperature range allows strong interaction between Fe3O4 and HAp molecules. The second one corresponds to the rearrangement of the CO32− and HPO4− groups present in HAp. This is in good agreement with the thermogravimetric analysis.

Figure 4.

DSC analysis of Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles.

Abbreviations: DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; Fe3O4, iron oxide; HAp, hydroxyapatite; NPs, nanoparticles.

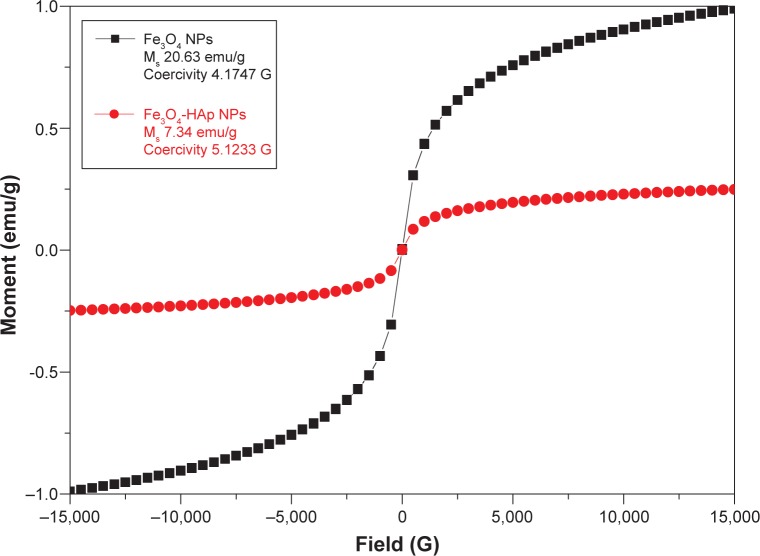

Vibrating sample magnetometry

The magnetic hysteresis loops for the Fe3O4 nanoparticles and the Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposites is shown in Figure 5. These materials exhibited strong magnetic behavior, with saturation magnetization of 20.639 and 7.34 emu/g and coercivity of 4.1747 and 5.1233 G, respectively, at 300 K. The magnetic properties are tabulated in Table 2. The saturation magnetization of pure Fe3O4 is lower than the value reported in the literature (92 emu/g).13 The samples show typical superparamagnetic behavior, with near zero coercivity and remanent magnetization, whereas pure HAp does not have any hysteresis loop. It is also clear from vibrating sample magnetometry that the magnetite particle in the composite structure is well within the single domain particle range and exhibits superparamagnetism. The magnetization value of the composites was lower than that of the pure Fe3O4 nanoparticles. The decreased saturation magnetization could be due to interaction between the iron core and the HAp shell, which decreases the magnetic moment.14,15

Figure 5.

Magnetic hysteresis loops of pure Fe3O4 and Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4, iron oxide; HAp, hydroxyapatite; NPs, nanoparticles; Ms, saturation magnetization.

Table 2.

Magnetic properties of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles

| Sample | Coercivity (G) | Saturation magnetization (emu/g) | Remanent magnetization (G) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 nanoparticle | 4.1747 | 20.639 | 0 |

| Fe3O4 -HAp nanocomposite | 5.1233 | 7.34 | 0 |

Abbreviations: Fe3O4, iron oxide; HAp, hydroxyapatite.

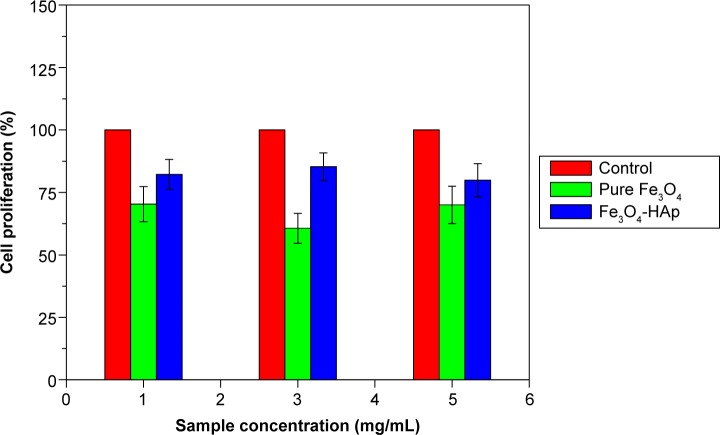

Cytotoxicity testing

In vitro cytotoxicity assays are the primary biocompatibility screening tests for a wide variety of materials used in the medical field. The MTT assay was done for the Fe3O4 and Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles using MG63 (osteosarcoma) cells. Three concentrations (1, 3, and 5 mg/mL) of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles and the Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposites were tested. The experiments were performed in triplicate. The mean values obtained are shown in Figure 6. The MTT assay procedure is explained in the flow chart given in Figure 2. The results show that the Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles enabled better cell proliferation than the pure Fe3O4 at the concentrations tested.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity test for pure Fe3O4 and Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles.

Abbreviations: Fe3O4, iron oxide; HAp, hydroxyapatite.

Magnetic induction hyperthermia is a technique that can be used to destroy cancer cells via their hysteresis loss when placed in an alternating magnetic field. The prepared nanocomposites have the capacity to generate heat in the presence of an alternating magnetic field. The temperature of the cancer cells is raised between 42°C and 46°C via the heat produced by our prepared composite materials. Although the heating efficiency of the prepared superparamagnetic Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposite is not demonstrated here, Hou et al16 showed that a similar Fe3O4-HAp nanocomposite was capable of magnetically inducing effective thermal destruction of cancer cells in vivo.

Conclusion

In this work, pure Fe3O4 was prepared by alkaline coprecipitation and HAp nanoparticles were prepared using an optimized sol-gel method. Fe3O4-HAp (0.7 w/w) nanocomposites were developed by wet milling. The prepared Fe3O4-HAp nanoparticles and its composite were characterized and confirmed by scanning electron microscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Their superparamagnetic nature was confirmed by vibrating sample magnetometry, and their thermal stability was confirmed by thermogravimetric analysis and differential scanning calorimetry. This nanostructured Fe3O4-HAp composite would be ideal for use in bone cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to their head of department, dean, principal, and management for providing the facilities to carry out this research. MS is grateful to TEQIP-II for providing a PhD research assistantship. This work was financially supported by DST (SB/S2/CMP-106/2013), New Delhi, and UGC (major, 42-907/2013SR), New Delhi.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jiang QL, Zheng SW, Hong RY, et al. Folic acid conjugated Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia and MRI in vitro and in vivo. Appl Surf Sci. 2014;307:224–233. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Corato R, Espinosa A, Lartigue L, et al. Magnetic hyperthermia efficiency in the cellular environment for different nanoparticle designs. Biomaterials. 2014;35:6400–6411. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pankhurst QA, Connolly J, Jones SK, Dobson J. Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2003;36:R167–R181. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bear JC, Yu B, Blanco-Andujar C, et al. A low cost synthesis method for functionalised iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia from readily available materials. Faraday Discuss. 2014;175:83–95. doi: 10.1039/c4fd00062e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnemain B. Superparamagnetic agents in magnetic resonance imaging: physicochemical characteristics and clinical applications – a review. J Drug Target. 1998;6:167–174. doi: 10.3109/10611869808997890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh RK, El-Fiqi AM, Patel KD, Kim HW. A novel preparation of magnetic hydroxyapatite nanotubes. Mater Lett. 2012;75:130–133. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karunamoorthi R, Kumar GS, Prasad AI, Vatsa RK, Thamizhavel A, Girija EK. Fabrication of a novel biocompatible magnetic biomaterial with hyperthermia potential. J Am Ceram Soc. 2014;97:1115–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami S, Hosono T, Jeyadevan B, Kamitakahara M, Ioku K. Hydrothermal synthesis of magnetite/hydroxyapatite composite material for hyperthermia therapy for bone cancer. J Am Ceram Soc. 2008;116:950–954. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki T, Nakatsuka R, Murase K, Takata H, Nakamura H, Watano S. Simple and rapid synthesis of magnetite/hydroxyapatite composites for hyperthermia treatments via a mechanochemical route. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:9365–9378. doi: 10.3390/ijms14059365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donadel K, Felisberto MD, Laranjeira MC. Preparation and characterization of hydroxyapatite-coated iron oxide particles by spray-drying technique. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2009;81:179–186. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652009000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tampieri A, D’Alessandro T, Sandri M, et al. Intrinsic magnetism and hyperthermia in bioactive Fe-doped hydroxyapatite. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta AK, Gupta M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3995–4021. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bretcanu O, Spriano S, Brovarone C, Verne E. Synthesis and characterization of coprecipitation-derived ferromagnetic glass-ceramic. J Mater Sci. 2006;41:1029–1037. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng J, Ni X, Zheng H, Li B, Zhang X, Zhan D. Preparation of Fe (core)/SiO2 (shell) composite particles with improved oxidation resistance. Mater Res Bull. 2006;41:1424–1429. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramanujan RV, Yeow YY. Synthesis and characterization of polymer-coated metallic magnetic materials. Mater Sci Eng C. 2005;25:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou CH, Hou SM, Hsueh YS, Lin J, Wu HC, Lin FH. The in vivo performance of biomagnetic hydroxyapatite nanoparticles in cancer hyperthermia therapy. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3956–3960. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]