Abstract

Background

Phenotypes of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) are not well characterized.

Objective

To describe clinical features of EoE patients with predefined phenotypes, determine predictors of these phenotypes, and make inferences about the natural history of EoE.

Design

Retrospective study.

Setting

Tertiary care center.

Patients

Incident EoE cases from 2001–2011 who met consensus diagnostic guidelines.

Interventions

n/a

Main outcome measurements

Endoscopic phenotypes, including fibrostenotic, inflammatory, or mixed. Other groups of clinical characteristics examined included atopy, level of esophageal eosinophilia, and age of symptom onset. Multinominal logistic regression assessed predictors of phenotype status.

Results

Of 379 cases of EoE identified, there were no significant phenotypic differences by atopic status or level of eosinophilia. Those with the inflammatory phenotype were more likely to be younger than those with mixed or fibrostenotic (13 vs 29 vs 39 years, respectively; p<0.001), and less likely to have dysphagia, food impaction, and esophageal dilation (p<0.001 for all). The mean symptom length prior to diagnosis was shorter for inflammatory (5 vs 8 vs 8 years; p=0.02). After multivariate analysis, age and dysphagia independently predicted phenotype. The OR for fibrostenosis for each 10-year increase in age was 2.1 (1.7–2.7). The OR for dysphagia was 7.0 (2.6–18.6).

Limitations

Retrospective, single-center study.

Conclusions

In this large EoE cohort, the likelihood of fibrostenosing disease increased markedly with age. For every ten year increase in age, the odds of having a fibrostenotic EoE phenotype more than doubled. This association suggests that the natural history of EoE is a progression from an inflammatory to a fibrostenotic disease.

Keywords: eosinophilic esophagitis, phenotype, stricture, inflammation, natural history

Introduction

Over the past decade, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has rapidly emerged as an important cause of upper GI disease.1 EoE is defined as a clinicopathologic immune/allergen-mediated disorder characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and a marked eosinophilic infiltrate on esophageal biopsy.2 EoE appears to be a chronic disease, but there are few cohorts that have been observed long-term without therapeutic interventions.3, 4 In general, patients with EoE tend to be younger, male, white, and have associated atopic disorders.5 Dysphagia is the hallmark symptom of EoE, and EoE is the cause in more than 50% of cases of food impaction presenting to the emergency department.2, 5, 6 Typical findings on endoscopy include esophageal rings, linear furrows, white plaques or exudates, decreased vascularity, strictures, and mucosal fragility.7, 8

Despite these commonalities, there can be substantial variability in EoE at the patient level. It is well recognized that clinical and endoscopic features of children and adults with EoE differ.2, 5, 7, 9–13 Children tend to present with heartburn, vomiting, abdominal pain, feeding intolerance, or failure to thrive, while adults primarily present with dysphagia. While adults often have esophageal rings and strictures requiring dilation, children tend to have more furrows, plaques, and decreased vascularity on endoscopy. Similarly, while atopy is common in EoE, it is by no means universal.9, 14–17 Recently, there has been a question of whether different EoE phenotypes are responsible for divergent clinical presentations and outcomes.2, 18, 19 However, it is unknown whether specific phenotypes accurately characterize subgroups of patients with EoE and whether these phenotypes are the result of disease progression. It is also unknown whether EoE is a disease consisting of one or more discrete subtypes, or whether it is a single condition with changes in expression over time. In the latter conception, the manifestations primarily present in children and young adults might represent an early inflammatory phase, while the manifestations in adults would represent chronic fibrostenotic manifestations which are sequelae of this inflammation.

The aim of this study was to describe the clinical features of EoE patients with predefined phenotypes, determine predictors of these phenotypes, and make inferences about the natural history of EoE. The phenotypes examined include inflammatory, fibrostenotic, and mixed phenotypes based on endoscopy, as well as defined clinical characteristics such as atopic status, severity of esophageal eosinophilia, and onset of disease.

Methods

Study design, data source, and phenotype definitions

This was a retrospective study conducted at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing. Using the UNC EoE Clinicopathologic database from 2001–2011, subjects with an incident diagnosis of EoE made at UNC who met consensus diagnostic guidelines were included. Specifically, all patients had symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, ≥15 eos/hpf (hpf area=0.24 mm2), and did not respond to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial.2, 20 Details of the development of this database and confirmation of EoE case status have previously been described.9, 21, 22 This study was approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board.

Data were extracted from electronic medical records, endoscopy reports, and pathology records. Specific data included: demographics (age at diagnosis, gender, race); symptoms; duration of symptoms prior to EoE diagnosis; co-existing atopic disease (allergic rhinitis or sinusitis, asthma, or documented food allergy demonstrated by either symptomatic evidence of allergy with reintroduction of a food or by testing directed by an Allergist); and endoscopic findings (rings, strictures, esophageal narrowing, linear furrows, white plaques or exudates, decreased vascularity, crêpe-paper mucosa, erosive esophagitis, and hiatal hernia) and maneuvers (dilation). For histologic assessment, the maximum eosinophil count (eos/hpf; hpf area = 0.24 mm2) had been determined for clinical purposes using a standard protocol which has been shown to have excellent interobserver correlation for both attending and resident pathologists.23, 24

EoE phenotypes were defined a priori as follows. Endoscopic phenotypes reflected the degree of inflammation versus remodelling noted on esophageal examination. The phenotypes were defined as fibrostenotic if there were esophageal rings, narrowing, or strictures and no evidence of linear furrows or white plaques; as inflammatory if there were furrows, plaques, or a normal esophagus and no evidence of fibrostenotic changes; and as mixed if there were a combination of findings. Furrows were considered an inflammatory change based on evidence that biopsies from these areas show a highly eosinophilic infiltrate, and that furrowing is rapidly reversible with topical steroids.25–28 We also assessed cases of EoE by other baseline disease characteristics. Atopy was defined as subjects with allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, dermatitis, asthma, or food allergy. We stratified esophageal eosinophilia by tertiles (15–50 eos/hpf, 51–99, eos/hpf and ≥100 eos/hpf). Disease onset was separated into childhood disease onset (first symptoms at <18 yrs) versus adult disease onset. Because we had data concerning symptom duration prior to diagnosis of EoE, we estimated approximate date of disease onset by subtracting the pre-diagnosis symptom duration from the date of diagnosis. For instance, an adult diagnosed at age 30 would be considered to have childhood disease onset if symptoms had been present for more than 12 years.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of the EoE population in general, and then to characterize features of each of the EoE phenotypes. Features were then compared between the different phenotype definitions. Specifically, the three phenotypes were compared, the atopic/non atopic subjects were compared, the eosinophil tertiles were compared, and the age of onset was compared. Means were compared with t-tests and proportions were compared by chi-square. Finally, multinominal logistic regression was performed to assess predictors of phenotype status amongst the three phenotypes. Odds ratios (ORs) were assessed for multiple factors based on the initial bivariate analysis including age (10 year increments), gender, race, symptoms (dysphagia, heartburn, abdominal pain, vomiting), atopy, food allergies, and eosinophil counts. The model was then reduced using a backwards elimination strategy that removed factors that were not significant at the p < 0.05 level. We analyzed a separate model that included symptom duration, as this was colinear with age.

Results

Characteristics of EoE cases

A total of 379 EoE cases were identified in the database (Table 1). The mean age was 25 years (ranging from 6 months to 82 years), 73% were male, and 81% were white. The most common symptoms were dysphagia (66%), heartburn (39%), and food impaction (28%), with a mean duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis of 7 years. More than one-third of patients had some form of atopy. On endoscopy, typical findings of EoE were common, with 40% having esophageal rings and 40% having linear furrows. The average maximum eosinophil count was 86 eos/hpf.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with EoE (n = 379)

| Characteristic | N (%) or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (mean years ± SD, range) | 25.3 ± 18.7 (0.6–82) |

| Adults ≥ 18 years | 199 (53) |

| Males (n, %) | 278 (73) |

| Whites (n, %) | 305 (81) |

| Symptoms (n, %) | |

| Dysphagia | 244 (66) |

| Food impaction | 100 (28) |

| Heartburn | 139 (39) |

| Chest pain | 33 (9) |

| Abdominal pain | 83 (23) |

| Nausea | 38 (11) |

| Vomiting | 91 (26) |

| Failure to thrive | 49 (14) |

| Symptom length prior to diagnosis (mean years ± SD) | 7.1 ± 8.8 |

| Atopic diseases (n, %)* | |

| Allergic rhinitis/sinusitis/dermatitis | 125 (38) |

| Asthma | 89 (27) |

| Food allergy | 62 (19) |

| Endoscopic findings (n, %)† | |

| Normal | 63 (17) |

| Rings | 148 (40) |

| Stricture | 66 (18) |

| Narrowing | 44 (12) |

| Linear furrows | 150 (40) |

| White plaques | 81 (22) |

| Decreased vascularity | 58 (16) |

| Crêpe-paper mucosa | 23 (6) |

| Erosive esophagitis | 89 (24) |

| Hiatal hernia | 35 (9) |

| Dilation performed | 76 (20) |

| Maximum eosinophil count (mean eos/hpf ± SD; range) | 85.7 ± 81.1 (15–609) |

Data were available on atopic status for 332 subjects

Data were available on EGD findings for 374 subjects

Fibrotic, inflammatory, and mixed phenotypes and phenotype predictors

When the 374 patients with endoscopic data were divided into phenotypes, 134 (36%) were inflammatory, 163 (43%) were mixed, and 77 (21%) were fibrostenotic (Table 2). Those with an inflammatory phenotype were on average much younger than those with mixed or fibrostenotic (13 vs 29 vs 39 years, respectively; p <0.001). Dysphagia was less likely in inflammatory compared to mixed or fibrostenotic (36% vs 77% vs 92%; p<0.001), as were food impaction (15% vs 37% vs 39%; p<0.001) and esophageal dilation (0% vs 24% vs 47%; p<0.001). Abdominal pain, vomiting, and failure-to-thrive were more common in the inflammatory phenotype (p<0.001 for all), as were atopy and food allergies (p<0.05). The mean symptom length prior to diagnosis was shorter for inflammatory compared to mixed and fibrostenotic (5 vs 8 vs 8 years; p=0.02). The maximum eosinophil counts did not significantly vary between the groups (84 vs 80 vs 102; p=0.12). These results were unchanged in a supplemental analysis comparing the inflammatory EoE cases to EoE cases with any element of fibrostenosis (ie combining the mixed and fibrostenotic groups) (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of inflammatory, mixed, and fibrostenotic phenotypes of EoE

| Inflammatory (n = 134; 36%) | Mixed (n = 163; 43%) | Fibrostenotic (n = 77; 21%) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 13.3 ± 14.4 | 29.1 ± 16.9 | 39.2 ± 16.3 | < 0.001 |

| Adults ≥ 18 years | 26 (19) | 111 (68) | 62 (81) | < 0.001 |

| Males (n, %) | 99 (74) | 120 (74) | 54 (70) | 0.82 |

| Whites (n, %) | 92 (69) | 142 (88) | 68 (88) | < 0.001 |

| Symptoms (n, %) | ||||

| Dysphagia | 47 (36) | 123 (77) | 70 (92) | < 0.001 |

| Food impaction | 15 (12) | 56 (37) | 27 (39) | <0.001 |

| Heartburn | 63 (49) | 57 (37) | 18 (27) | 0.008 |

| Chest pain | 8 (6) | 18 (12) | 7 (10) | 0.25 |

| Abdominal pain | 51 (39) | 24 (16) | 8 (12) | < 0.001 |

| Nausea | 20 (15) | 6 (4) | 10 (15) | 0.003 |

| Vomiting | 54 (41) | 22 (15) | 11 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Failure to thrive | 33 (26) | 13 (9) | 1 (1) | < 0.001 |

| Symptom length prior to dx (mean years ± SD) | 5.3 ± 7.6 | 8.3 ± 9.4 | 8.4 ± 9.2 | 0.02 |

| Atopic diseases (n, %) | ||||

| Allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, dermatitis | 50 (39) | 59 (39) | 13 (20) | 0.01 |

| Asthma | 35 (27) | 41 (27) | 13 (20) | 0.47 |

| Food allergy | 32 (27) | 20 (15) | 9 (18) | 0.05 |

| Endoscopic findings (n, %) | ||||

| Normal | 63 (47) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Rings | 0 | 87 (53) | 61 (79) | - |

| Stricture | 0 | 31 (19) | 35 (45) | - |

| Narrowing | 0 | 31 (19) | 13 (17) | - |

| Linear furrows | 56 (42) | 94 (58) | 0 | - |

| White plaques | 39 (29) | 42 (26) | 0 | - |

| Decreased vascularity | 25 (19) | 24 (15) | 9 (12) | 0.38 |

| Crêpe-paper | 7 (5) | 12 (7) | 4 (5) | 0.69 |

| Erosive esophagitis | 14 (10) | 48 (29) | 27 (35) | < 0.001 |

| Hiatal hernia | 2 (1) | 23 (14) | 10 (13) | < 0.001 |

| Dilation performed | 0 | 39 (24) | 37 (47) | - |

| Max eosinophil count (mean eos/hpf ± SD) | 84.2 ± 75.9 | 79.3 ± 78.4 | 102.3 ± 95.4 | 0.12 |

p values calculated using a one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables; p values were not compared for the endoscopic findings used to construct the phenotype groups.

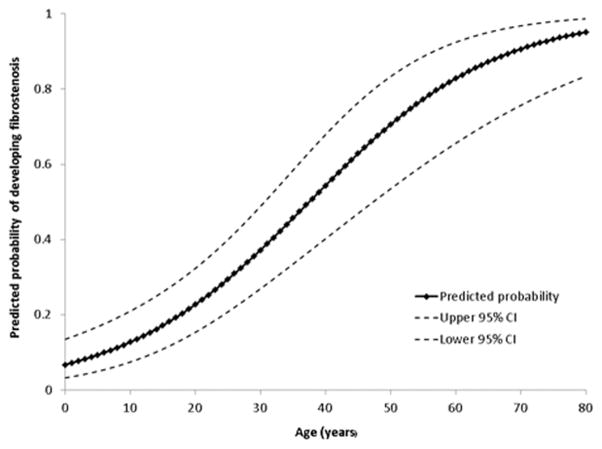

After multivariate analysis, only age at diagnosis and dysphagia were independent predictors of phenotype status. The OR for a 10 year increase in age for a mixed phenotype compared to inflammatory was 1.64 (95% CI 1.35–1.99) and for fibrostenotic was 2.14 (1.70–2.70). This indicates that for every decade of life, the odds of developing a fibrostenotic phenotype more than doubles. The predicted probability of developing a fibrosteontic EoE phenotype by age is graphed in Figure 1. The ORs for the presence of dysphagia as a predictor of mixed or fibrostenosing phenotype were 3.07 (1.71–5.49) and 7.00 (2.63–18.64), respectively. When symptom duration prior to EoE was assessed separately, the findings were similar. The OR for each 1 year of symptoms prior to EoE diagnosis for a fibrostenotic vs inflammatory phenotype was 1.05 (1.01–1.10), indicating that the odds of developing fibrostenosis increased 5% with every year of symptoms prior to diagnosis. The OR for a 10 year symptom duration prior to EoE diagnosis was 1.60 (1.05–2.44).

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of developing a fibrostenosing phenotype of EoE based on age.

Atopy, eosinophil counts and age of disease onset

There were 177 EoE cases with atopy, 128 in the highest tertile of eosinophil counts (≥100 eos/hpf), and 172 with childhood onset of disease. Those with atopy tended to be diagnosed at an earlier age than those without atopy (22 vs 26 yrs; p=0.06), but there were no other differences by atopic status for gender, race, symptoms, endoscopy findings, or eosinophil counts (Supplemental Table 2).

For the eosinophilia phenotype, there were no significant differences by age, gender, race, symptoms, atopic status, or endoscopy findings based on eosinophil counts at diagnosis (Supplemental Table 3).

Those with childhood onset of EoE were more commonly male (81% vs 67%; p<0.001) and non-white (25% vs 15%; p=0.02), had more abdominal pain, vomiting, and failure-to-thrive (p<0.01 for all), and less dysphagia (p<0.001) than those with adult onset. While those with childhood onset were more likely to have a normal endoscopic exam (28% vs 8%; p<0.001), there was no difference in eosinophil count by age of symptom onset (Table 3). These results were unchanged in a supplemental analysis where childhood onset was defined as age < 12 years (see Supplemental Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of EoE characteristics by pediatric versus adult onset of disease

| Peds. onset (n = 172; 45%) | Adult onset (n = 207; 55%) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 12.7 ± 11.3 | 35.7 ± 17.1 | -- |

| Adults ≥ 18 years | -- | -- | -- |

| Males (n, %) | 140 (81) | 138 (67) | 0.001 |

| Whites (n, %) | 129 (75) | 176 (85) | 0.02 |

| Symptoms (n, %) | |||

| Dysphagia | 75 (44) | 169 (83) | < 0.001 |

| Food impaction | 35 (21) | 65 (35) | 0.003 |

| Heartburn | 73 (43) | 66 (35) | 0.12 |

| Chest pain | 8 (5) | 25 (13) | 0.005 |

| Abdominal pain | 51 (30) | 32 (17) | 0.004 |

| Nausea | 17 (10) | 21 (11) | 0.72 |

| Vomiting | 62 (37) | 29 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Failure to thrive | 40 (24) | 9 (5) | < 0.001 |

| Symptom length prior to dx (mean years ± SD) | 6.4 ± 8.2 | 8.2 ± 9.7 | 0.10 |

| Atopic diseases (n, %) | |||

| Allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, dermatitis | 36 (39) | 61 (33) | 0.28 |

| Asthma | 51 (31) | 38 (20) | 0.03 |

| Food allergy | 36 (24) | 26 (17) | 0.11 |

| Endoscopic findings (n, %) | |||

| Normal | 47 (28) | 16 (8) | < 0.001 |

| Rings | 33 (19) | 115 (56) | < 0.001 |

| Stricture | 14 (8) | 52 (25) | < 0.001 |

| Narrowing | 13 (8) | 31 (15) | 0.02 |

| Linear furrows | 60 (35) | 90 (44) | 0.08 |

| White plaques | 42 (25) | 39 (19) | 0.19 |

| Decreased vascularity | 38 (22) | 20 (10) | 0.001 |

| Crêpe-paper | 16 (9) | 7 (3) | 0.02 |

| Erosive esophagitis | 42 (25) | 47 (23) | 0.71 |

| Hiatal hernia | 6 (4) | 29 (14) | < 0.001 |

| Dilation performed | 13 (8) | 63 (31) | < 0.001 |

| Max eosinophil count (mean eos/hpf ± SD) | 81.8 ± 69.7 | 88.9 ± 89.4 | 0.40 |

p values calculated using a t-test for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables.

Discussion

With increasing knowledge about EoE, the variability in the disease has been recognized,2 and differences in characteristics between adults and children7, 9–12 and by race or gender have been described.29–31 This has raised the question of whether underlying EoE phenotypes are responsible for different clinical presentations and outcomes, and whether such phenotypes might impact on or be the result of the natural history of the condition. The purpose of this study was to characterize clinical features of predefined EoE phenotypes, determine predictors of these phenotypes, and make inferences about the natural history of EoE.

We found that fibrostenotic, inflammatory, and mixed phenotypes were associated with significant clinical differences between groups of EoE patients. In particular, those with an inflammatory phenotype were younger, less likely to have dysphagia, food impaction, or esophageal dilation, and more likely to have abdominal pain, vomiting, failure-to-thrive, and atopy. Importantly, the mean symptom length prior to diagnosis was shorter for inflammatory compared to the mixed and fibrostenotic phenotypes. This suggests that EoE may progress from an inflammatory to fibrostenotic disease, and the multivariate analysis demonstrates this change in risk over time. For every 10 year increase in age, the odds of having a fibrostenotic phenotype more than doubles. The odds were similar for longer duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis. In contrast, baseline atopic status or eosinophil count were not associated with important differences in clinical characteristics. High eosinophil counts were also seen in EoE patients with a fibrostenotic phenotype and a long symptom duration prior to diagnosis, suggesting that the inflammation in this group is not “burning out,” or becoming less severe over time.

Our findings support a trend of new thinking about EoE. In recent years there has been much discussion about possible phenotypes of EoE, though there are few published data on this topic.2, 18, 32, 33 It has been well described that symptoms differ between adults and children and appear to progress, with failure to thrive and feeding intolerance in the youngest children, then abdominal pain, vomiting/regurgitation, and heartburn in older children, then dysphagia and food impaction in adolescents and adults.9–12 Similarly, endoscopic findings have been reported to vary by age as well, with a normal appearing esophagus, linear furrows, and white plaques more common in children, and esophageal rings, strictures, and narrowing more common in adults.7, 9, 13 In natural history studies, while there are few children who have been observed for many years without treatment,3, 14, 15, 34, 35 progression from inflammatory to fibrostenotic phenotypes has been noted anecdotally.

In our study, there was highly active eosinophilic inflammation in all patients, regardless of phenotype. One could postulate that with longer exposure to inflammation, there is a higher risk of fibrosis. Indeed, eosinophilic inflammation resulting in esophageal fibrosis has been well described in studies of the pathogenesis of EoE. Aceves and colleagues first reported sub-epithelial fibrosis in children with EoE,36 and this has been confirmed in both children and adults.37–39 Fibrosis appears to be mediated by active eosinophilic and mastocytotic inflammation in the esophageal mucosa,36, 40–42 and may involve deeper layers of the esophagus wall, as suggested by endoscopic ultrasound imaging.43–45 Kwiatek, Hirano, and colleagues have used a novel functional lumen imaging probe to characterize decreased esophageal compliance in patients with EoE, a result of ongoing esophageal remodelling and fibrosis.46 They have also shown that esophageal compliance correlates with endoscopically-defined phenotypes of EoE,26, 47 similar to the phenotypes used in this study. Our findings are also consistent with recent data presented by Schoepfer, Straumann, and colleagues showing that the duration of untreated inflammation is strongly associated with stricture development.48 Specially, they found that 17% of subjects with 0–2 years of symptom duration had a stricture, compared to 38% with 9–11 years and 67% with more than 20 years. Taken in the context of these data, our results support the hypothesis that fibrostenotic complications are likely the result of chronic inflammation leading to disease progression in EoE.

In addition to improving our understanding of the pathogenesis of EoE, recognition of phenotypes of EoE may also have implications for treatment decisions and outcome assessment. For example, if EoE is progressive, there may be an impetus to aggressively treat eosinophilic inflammation in subjects who have not yet developed fibrostenotic complications in order to prevent esophageal stricture development. Data suggest that children who are treated may not have the severe phenotypes that are seen in adults who are diagnosed after prolonged symptoms,34, 49, 50 and that long-term topical corticosteroid treatment might alter the natural history of EoE.51 EoE phenotype might also dictate specific treatments. Patients with fibrostenosis might require dilation as a primary treatment, particularly since symptoms and levels of esophageal inflammation correlate poorly or not at all.19, 33, 52, 53 Additionally, for drug development, patients with a predominantly inflammatory phenotype, as opposed to those with established fibrostenosis, may be a desirable target population for new medications with a strong anti-eosinophil/anti-inflammatory effect.

In interpreting the results from this study, there are potential limitations. First, this is a retrospective study from a single center, so the generalizability of the results is unclear. However, the characteristics of this EoE population are quite similar to EoE patients reported from other centers and practice settings. Because it relies on endoscopically-defined phenotypes, the reproducibility of these findings may be questioned (for example, the definition of “narrowing” is not standardized). However, recent work suggests there is fair to good agreement among gastroenterologists for endoscopic findings of EoE.8, 54 Additionally, the data presented here are cross-sectional in nature, but are being used to make inferences about disease progression. While the ideal study design to accomplish this would be a long-term prospective cohort study, it is neither practical nor ethical to observe a population of EoE cases for a decade or more to determine the true rate of fibrostenotic complications. Furthermore, increasing risk for fibrostenotic progression was found to be not only associated with age (a cross-sectional measure), but also with symptom duration prior to diagnosis, a factor that capitulates retrospectively what a prospective cohort study would measure. However, we acknowledge that confounding factors (for example, concomitant use by atopic patients of intranasal or inhaled corticosteroids) could impact the course of the disease, and therefore the observed EoE phenotype. Finally, this paper is limited to clinicopathologic phenotypes. Future studies might determine whether genetically-defined phenotypes of EoE exist and might be used for diagnosis, prognosis, or to guide therapy.

The strengths of this study should also be acknowledged. This is large sample of well-characterized EoE cases that provides sufficient power to subdivide the population in multiple phenotypes. We selected phenotypes a priori that match the evolving understanding of EoE. In addition, the predictive analysis using multinomial regression can provide patients with quantifiable data as to what to expect for disease progression.

In conclusion, in this large cohort of subjects with EoE, the likelihood of fibrostenosing disease increased with age. For every ten year increase in age, the odds of having a fibrostenotic EoE phenotype more than doubled. The association of fibrostenosis with age suggests that the natural history of EoE is a progression from an inflammatory to a fibrostenotic disease. Further work should confirm these findings, and assess whether these phenotypes predict response to various therapies or prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was supported, in part, by NIH Award K23 DK090073.

References

- 1.Katzka DA. Eosinophilic Esophagitis: From Rookie of the Year to Household Name. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:370–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: Updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, et al. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11. 5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1660–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Straumann A. The natural history and complications of eosinophilic esophagitis. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21:575–87. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellon ES. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1066–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, et al. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HP, Vance RB, Shaheen NJ, et al. The Prevalence and Diagnostic Utility of Endoscopic Features of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:988–996. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62:489–95. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straumann A, Aceves SS, Blanchard C, et al. Pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis: similarities and differences. Allergy. 2012;67:477–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucendo AJ, Sanchez-Cazalilla M. Adult versus pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: important differences and similarities for the clinician to understand. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:733–45. doi: 10.1586/eci.12.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:940–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408263510924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vashi RA, Kagalwalla AF, Amsden K, et al. Systematic, endoscopic assessment demonstrates increased fibrostenotic and decreased inflammatory esophageal features in adults compared with children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144 (Suppl 1):S494, Su1862. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, et al. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:30–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181788282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assa’ad AH, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: an 8-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:731–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penfield JD, Lang DM, Goldblum JR, et al. The Role of Allergy Evaluation in Adults With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:22–7. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181a1bee5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy-Ghanta S, Larosa DF, Katzka DA. Atopic Characteristics of Adult Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:531–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prieto R, Richter JE. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: an update on medical management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:324. doi: 10.1007/s11894-013-0324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirano I. Therapeutic End Points in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Is Elimination of Esophageal Eosinophils Enough? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:750–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dellon ES, Chen X, Miller CR, et al. Tryptase staining of mast cells may differentiate eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:264–71. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellon ES, Chen X, Miller CR, et al. Diagnostic utility of major basic protein, eotaxin-3, and leukotriene enzyme staining in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1503–11. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellon ES, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, et al. Inter- and intraobserver reliability and validation of a new method for determination of eosinophil counts in patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1940–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1005-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Speck O, Woodward K, Covey S, et al. A training curriculum for pathologists yields highly reproducible esophageal eosinophil counts. Gastroenterology. 2013;144 (Suppl 1):S499, Su 1881. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta SK, Fitzgerald JF, Chong SK, et al. Vertical lines in distal esophageal mucosa (VLEM): a true endoscopic manifestation of esophagitis in children? Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:485–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Z, Nicodeme F, Chen J, et al. Esophageal compliance parameters assessed with the Functional Luminal Imaging Probe (FLIP) among eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2013;144 (Suppl 1):S487. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saffari H, Peterson KA, Fang JC, et al. Patchy eosinophil distributions in an esophagectomy specimen from a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis: Implications for endoscopic biopsy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:798–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–37. 1537 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sperry SLW, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ, et al. Influence of race and gender on the presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:215–21. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bohm M, Malik Z, Sebastiano C, et al. Mucosal Eosinophilia: Prevalence and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Symptoms and Endoscopic Findings in Adults Over 10 Years in an Urban Hospital. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:567–574. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31823d3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Dias JA, et al. Race may play a role in the clinical presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1263. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Z, Kahrilas PJ, Xiao Y, et al. Functional luminal imaging probe topography: an improved method for characterizing esophageal distensibility in eosinophilic esophagitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:97–107. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12470017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohm ME, Richter JE. Review article: oesophageal dilation in adults with eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:748–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menard-Katcher P, Marks KL, Liacouras CA, et al. The natural history of eosinophilic oesophagitis in the transition from childhood to adulthood. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:114–21. doi: 10.1111/apt.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198–206. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, et al. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chehade M, Sampson HA, Morotti RA, et al. Esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:319–28. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31806ab384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucendo AJ, Arias A, De Rezende LC, et al. Subepithelial collagen deposition, profibrogenic cytokine gene expression, and changes after prolonged fluticasone propionate treatment in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1037–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aceves SS. Tissue remodeling in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: what lies beneath the surface? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1047–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aceves SS, Chen D, Newbury RO, et al. Mast cells infiltrate the esophageal smooth muscle in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, express TGF-beta1, and increase esophageal smooth muscle contraction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1198–204. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng E, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Tissue remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1175–87. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00313.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keshishian J, Vrcel V, Estores D, et al. Mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis: Trends in inflammatory and fibrostenotic phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2013;144 (Suppl 1):S495, Su1865. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevoff C, Rao S, Parsons W, et al. EUS and histopathologic correlates in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:373–7. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.116569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox VL, Nurko S, Teitelbaum JE, et al. High-resolution EUS in children with eosinophilic “allergic” esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:30–6. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:400–9. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwiatek MA, Hirano I, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Mechanical properties of the esophagus in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:82–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicodeme F, Hirano I, Chen J, et al. Esophageal Distensibility as a Measure of Disease Severity in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoepfer A, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Duration of untreated inflammation represents the main risk factor for stricture development in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144 (Suppl 1):S485, Su1832. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobs JW, Bohm M, Gupta A, et al. Most children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) have a favorable outcome as young adults. Gastroenterology. 2013;144 (Suppl 1):S487, Su1837. doi: 10.1111/dote.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeBrosse CW, Franciosi JP, King EC, et al. Long-term outcomes in pediatric-onset esophageal eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schoepfer A, Portmann S, Safroneeva E, et al. Influence of long-term treatment with topical corticosteroids on natural course of eosinophilic esophagitis and correlation between symptoms and endoscopy, histology, and blood eosinophils. Gastroenterology. 2013;144 (Suppl 1):S154, 878. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bohm M, Richter JE, Kelsen S, et al. Esophageal dilation: simple and effective treatment for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis and esophageal rings and narrowing. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23:377–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morrow JB, Vargo JJ, Goldblum JR, et al. The ringed esophagus: histological features of GERD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:984–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peery AF, Cao H, Dominik R, et al. Variable reliability of endoscopic findings with white-light and narrow-band imaging for patients with suspected eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:475–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.