Abstract

Background

The REversion-inducing Cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motif (RECK) is a well-known inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cellular invasion. Although high expression levels of RECK have already been correlated with a better clinical outcome for several tumor types, its main function, as well as its potential prognostic value for breast cancer patients, remain unclear.

Methods

The RECK expression profile was investigated in a panel of human breast cell lines with distinct aggressiveness potential. RECK functional analysis was undertaken using RNA interference methodology. RECK protein levels were also analyzed in 1040 cases of breast cancer using immunohistochemistry and tissue microarrays (TMAs). The association between RECK expression and different clinico-pathological parameters, as well as the overall (OS) and disease-free (DFS) survival rates, were evaluated.

Results

Higher RECK protein expression levels were detected in more aggressive breast cancer cell lines (T4-2, MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T) than in non-invasive (MCF-7 and T47D) and non-tumorigenic (S1) cell lines. Indeed, silencing RECK in MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in elevated levels of pro-MMP-9 and increased invasion compared with scrambled (control) cells, without any effect on cell proliferation. Surprisingly, by RECK immunoreactivity analysis on TMAs, we found no association between RECK positivity and survival (OS and DFS) in breast cancer patients. Even considering the different tumor subtypes (luminal A, luminal B, Her2 type and basal-like) or lymph node status, RECK remained ineffective for predicting the disease outcome. Moreover, by multivariate Cox regression analysis, we found that RECK has no prognostic impact for OS and DFS, relative to standard clinical variables.

Conclusions

Although it continues to serve as an invasion and MMP inhibitor in breast cancer, RECK expression analysis is not useful for prognosis of these patients.

Keywords: RECK, Breast cancer, Immunohistochemistry, Tissue microarray, Biomarker

Background

Breast cancer is the first in incidence and the second in mortality among women [1]. Currently, a reduction in overall cancer death rates is due to a combination of earlier diagnosis and treatment improvement [1]. Nevertheless, breast cancer remains a worldwide health problem. The lack of more informative biomarkers to discriminate among patients according to the prognosis and clinical course complicates the choice of therapeutic strategy.

Metastasis development is the main death factor attributed to breast cancer [2]. The organized breakdown of the extracellular matrix (ECM) by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) is an essential event in the complex metastatic cascade [3]. Inhibitors of MMPs, known as tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs), and the membrane-associated MMP inhibitor RECK are also critical for controlling the maintenance of the ECM integrity due to their regulation of MMP function [4–7].

Elevated MMP expression and activity levels have been associated with poor prognosis in several cancer types [8–10]. Surprisingly, a higher expression of MMP inhibitors, such as TIMPs, correlates with a worse outcome for breast cancer patients [11–14]. This ambiguous nature of TIMPs may be due to the wide variety of TIMP functions, which are independent of their activities as MMP inhibitors [6]. However, this finding remains unclear.

RECK, another type of MMP inhibitor, has been shown to decrease cellular invasion [15], most likely by inhibiting the enzymatic activity of MMP-2, MMP-9 and MMP-14 [16, 17]. Additionally, RECK has been shown to decrease MMP-9 mRNA levels [18]. The potential prognostic power of RECK has already been reported for other tumors, such as pancreatic, liver, lung and colorectal cancers [19–23], where RECK expression is inversely correlated with MMP expression during tumor progression [23]. Thus, high expression levels of RECK correlate with a better clinical outcome [23].

However, in breast cancer, the RECK expression profile is controversial and remains unclear [24–27]. Moreover, no functional analysis in human mammary tumors has been previously reported. A retrospective study using 119 cases of breast cancer samples, suggests, similar to other cancer types, that a low expression of RECK indicates a shorter survival rate for patients with invasive breast cancer [24]. The available data indicated that lower RECK mRNA levels were expressed in tumor tissue samples than in normal breast tissue samples, and higher levels were found in invasive human breast cancer cells than in less aggressive ones [24–26].

In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the prognostic significance of RECK in breast cancer patient outcome. The RECK protein expression levels were analyzed in a large series (1040) of breast cancer cases using immunohistochemistry of tissue microarrays (TMAs). Furthermore, we investigated RECK function in mammary neoplasia using RECK-silenced human breast cancer cells, obtained by RNA interference methodology. Here, we present evidence supporting that, although RECK acts as a negative regulator of MMP-9 and invasion, its levels of expression fail to correlate with patient survival rates.

Methods

Patients and methods

All breast samples were obtained from patients diagnosed and treated at the A. C. Camargo Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil. TMAs were arranged from a series of 1040 cases of primary breast carcinoma from patients diagnosed between 1980 and 1999. Duplicate 1 mm cores from tumors were used in the TMAs. The median age of the patients was 55 years (range: 26–90 years). The tumor tissues were removed at surgery. The A. C. Camargo Hospital Ethics Committee approved this research (Process number: 1648/12) and waived the need for informed consent term.

Vimentin and pan-cytokeratin were used as tissue immunoreactivity and staining controls. RECK staining was performed using a monoclonal antibody diluted 1:200 (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA). Several patient and tumor characteristic data were available, including age, menopausal status, tumor size, lymph node stage, SBR stage (Scarff-Bloom-Richardson, histological classification method) and TNM tumor stage. The expression state of several biomarkers, such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone (PR), Her-2 and cytokeratins (CK5, CK6, CK8, CK14 and CK18), was also evaluated by two distinct pathologists.

The ScanScope XT device was used for slide scanning. The percentage of cells positively stained for RECK, and its staining pattern in the TMA core, was determined using the Spectrum Plus computational program, by a trained person. For each subject, at least three measurements were obtained, from two distinct slides, with samples represented in duplicate. The average of these three values was considered as the RECK immunoreactivity for each subject. RECK immunoreactivity values greater than the median were considered as positive (or high expression).

Cell lines and reagents

Six breast cell lines (S1, MCF-7, T47D, T4-2, MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T) with distinct tumorigenic and aggressiveness levels were used in this study [26]. The broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor (GM6001) was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA).

Viral transduction and shRNA experiments

For the inhibition of RECK expression, five different specific shRNA sequences (sequentially numbered from shRECK23 through shRECK27) were tested. These vectors and the structural ones belonged to the Mission® shRNA system (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Viral recombinant particles were generated by co-transfection of the 293FT virus packer cell line with these recombinant lentiviral vectors. Transduced cells were selected by the addition of 2 μg/mL puromycin.

Quantitative RT-PCR studies

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Its integrity and quantity were evaluated using a NanoDrop™ 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For cDNA synthesis, the SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase Kit was used (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out using QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen). The primers used to amplify RECK, MMP-9 and the endogenous control (18S ribosomal RNA) were obtained from a validated primer panel available from Qiagen (QuantiTect Primer Assays). Each experiment was carried out in duplicate. The relative expression levels were calculated according to the 2-∆∆Ct method [28].

Western blotting

Total extracts were prepared from each cell culture line. Equal protein amounts from each extract were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and then electro-transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blockade with BSA, these membranes were incubated with RECK (Cell Signaling) and Lamin A/C (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) antibodies, diluted at 1:1000 and 1:200, respectively. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with the appropriate secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) and visualized using the SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative densitometry of the electrophoretic band images was carried out using AlphaEaseFC software.

Gelatin zymography assays

Gelatin zymography of the conditioned media was used to assess the in vitro enzymatic activity levels of MMP-9 in RECK-silenced and scrambled MDA-MB-231 cells. These samples were fractionated by 10 % SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis co-polymerized with the enzyme substrate, 0.1 % denatured type I collagen (gelatin type A; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). After electrophoresis, the gels were washed at room temperature with 2.5 % Triton X-100, incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in substrate buffer containing 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.5) and 10 mM CaCl2. Gels were stained with Coomassie Blue R-250 (Sigma) and destained with 40 % methanol (Merck) and 10 % acetic acid (Merck) in water. Gelatinolytic activity was visualized as negatively staining bands. Each independent experiment was performed in duplicate. Quantitative densitometry of the electrophoretic band images was performed using the AlphaEaseFC software.

In vitro invasion assays

To assess the role of RECK in cellular invasiveness potential, RECK-deficient or scrambled control MDA-MB-231 cells were plated on top of Matrigel-coated 8-μm-pore transwells (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). These cells were maintained in the presence of GM6001 or its vehicle (DMSO) in serum-free medium. The medium present in the bottom chamber was supplemented with 10 % bovine serum, used as a chemo-attractant. Cells were allowed to invade for 36 h. Cells remaining at the top chamber were removed, and those present at the bottom of the filter were stained and fixed with Coomassie Blue 0.125 % in methanol:acetic acid:H2O (45:10:45, v/v/v) for 15 min. Using the ImageJ® program, the relative cellular invasion was quantified from the images obtained (10× objective lens) under each experimental condition. Non-tumorigenic S1 mammary cells were used as a negative control. Triplicate wells were utilized per condition in each independent experiment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data from patients was performed using R (http://www.r-project.org/) [29]. Chi-square tests were used to assess the association between RECK immunoreactivity and different clinico-pathological parameters. P-values were corrected for multiple tests by the False Discovery Rate procedure [30]. Kaplan-Meier (KM) plots were used for overall (OS) and disease-free (DFS) survival analysis, and the log-rank test was used to compare curves separated according to RECK expression. For KM analysis, 3 of 1040 subjects were identified as being outliers by Tukey’s criterion; thus, they were removed from the data analysis. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs). Subjects for whom no information on the analyzed covariates was available, were removed, with 940 of the 1040 subjects remaining for the Cox regression analysis.

Data obtained using the cell lines model were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 5.0 program. In this case, statistical significance was determined using the one way ANOVA variance analysis and the Tukey-Kramer test. The results were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

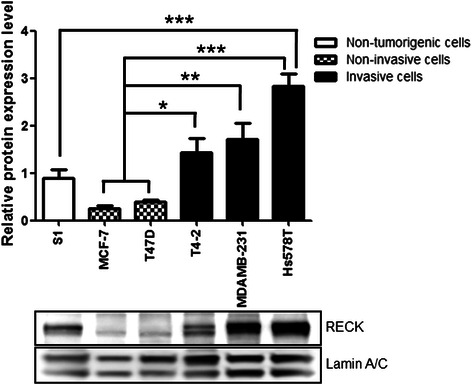

RECK protein expression levels in human breast cells correlates with invasiveness

In several tissue models, RECK expression was shown to be inversely related to oncogenesis [15, 31, 32], being expressed in normal tissues but not in many tumor cell lines and tumor samples [15, 32]. However, in breast cancer, the RECK expression profile remains uncertain and controversial [24–27]. To better understand this divergence, we quantified the RECK protein levels in a panel of breast cell lines with distinct aggressiveness levels, including non-tumorigenic (S1) cells, and non-invasive (MCF-7 and T47D) and invasive (T4-2, MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T) cancer cell lines (Fig. 1). We observed that more invasive cells (T4-2, MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T) displayed significantly higher (p < 0.05, p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) RECK protein levels than non-invasive breast cancer lineages (MCF-7 and T47D). Furthermore, RECK protein was significantly overexpressed in the highly invasive Hs578T cells (p < 0.001) compared with the non-malignant ones (Fig. 1). The doublet bands detected were possibly a result of RECK glycosylation [33]. Therefore, our results suggest that, unexpectedly, human breast cancer cells with a higher invasive potential express elevated levels of RECK (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Invasive breast cancer cells express higher levels of RECK than non-invasive and non-tumorigenic ones. Western blot assays were performed to analyze RECK protein expression levels in a panel of human breast cells. The lamin A/C protein level was used as the loading control and for normalization. The results are presented as the means ± standard error from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

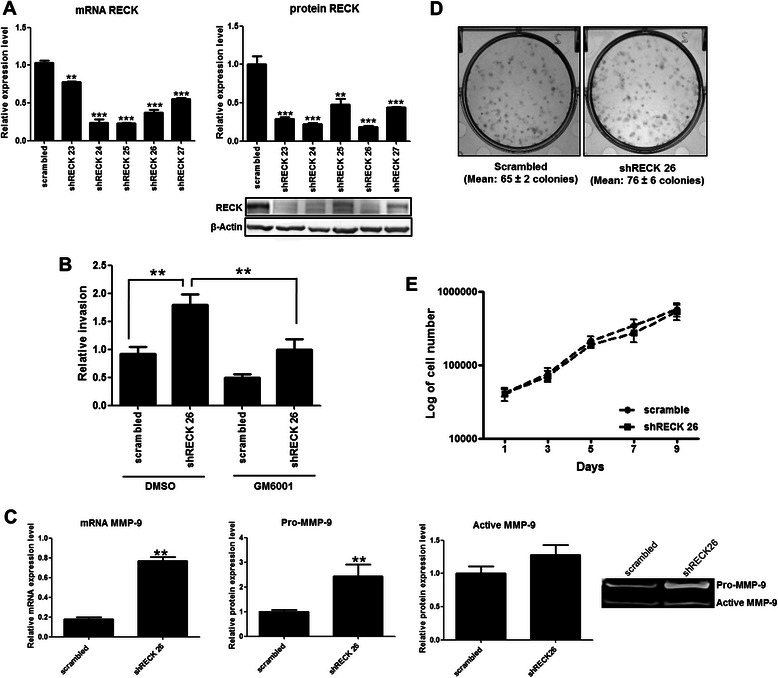

RECK down-modulates invasion and MMP-9 in highly invasive breast cancer cells

To further clarify the specific role of RECK in mammary neoplasia, we evaluated the functional activity of RECK. To this end, MDA-MB-231 cells, a highly invasive human breast cancer cell line, were used as a study model. The RECK expression level in MDA-MB-231 cells was silenced using different shRNA sequences (shRECK oligos numbered 23 through 27). Their ability to silence RECK was confirmed by qRT-PCR and Western blot assays (Fig. 2a). All of the sequences tested could decrease RECK expression at both the mRNA and protein levels. Subsequent functional assays were performed using shRECK26-transduced cells in which RECK protein expression was reduced by 80 % relative to the scrambled control (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

RECK functional analysis in the highly invasive MDA-MB-231 cells supports the role of RECK as an MMP inhibitor and negative modulator of cellular invasion. a RECK mRNA and protein expression levels in the MDA-MB-231 cells infected with lentiviral particles carrying different shRNA sequences specific for RECK inhibition (shRECK 23 through 27) or the scrambled control. The 18S ribosomal RNA expression and β-actin protein levels were used as endogenous controls in qRT-PCR and Western blot assays, respectively. b Transwell™ invasion assays were performed to assess the invasion capacity of scrambled control and RECK-deficient (shRECK26) cells that were treated with or without GM6001 (broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor). c MMP-9 mRNA and protein expression (pro-enzyme and active forms) levels in control (scrambled) and RECK-silenced cells quantified by qRT-PCR and Zymography assay, respectively. The 18S ribosomal RNA expression was used as the endogenous control in qRT-PCR assays. Proliferation analysis of scrambled and shRECK 26 cells by (d) colony formation assays and (e) growth curves. The results are presented as the means ± standard error from two independent experiments. **, p < 0.01 and ***, p < 0.001, all versus control (MDA-MB-231 scrambled cells)

First, we addressed the role of RECK in the invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells. To this end, the in vitro invasion capacities of scrambled control and RECK-downmodulated cells were compared in Transwell™ assays (Fig. 2b). Our results indicate that the reduction of RECK led to a significant increase (p < 0.01) in MDA-MB-231 invasion. Treatment with a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor (GM6001) suggests that this effect of RECK on the cell invasive capacity is largely MMP dependent because GM6001 could significantly (p < 0.01) reverse the RECK silencing effect in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2b). Additionally, we found that RECK-silenced cells express significantly higher levels of both MMP-9 (p < 0.01) mRNA and its pro-enzyme (p < 0.01) than scrambled control cells (Fig. 2c). Importantly, no influence of RECK was observed in MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation, as indicated in Fig. 2 (d and e). These results suggest that although its expression is correlated with increased breast cancer cell aggressiveness, RECK still serves as a negative regulator of cellular invasion and MMP-9 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells.

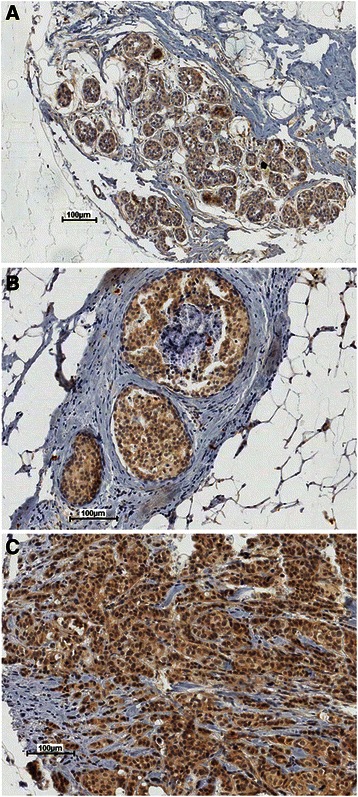

RECK expression in breast tumor tissue samples and its association with clinico-pathological parameters

Previous reports have supported the potential role of RECK as a molecular marker for the prognosis of several cancer types (23). However, the association between RECK expression and the outcome of breast cancer patients remains unclear. We evaluated RECK protein expression levels in a large series (n = 1040) of breast cancer cases by immunohistochemistry on TMAs. The staining pattern obtained for RECK in mammary tissue samples derived from benign proliferation, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive tumors is presented in Fig. 3. In all of these distinct breast tissues, RECK was predominantly expressed in epithelial cells, while the stromal cells were negative.

Fig. 3.

Representative immunohistochemistry images of the RECK staining profile detected in breast tissue samples show RECK expression in epithelial cells. a Benign proliferation, (b) ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and (c) invasive tumor samples analyzed in tissue microarray cores

All of the breast tumor samples included in this analysis were classified as positive or negative for RECK considering the intensity and percentage of stained cells (Methods). To evaluate the correlation between RECK expression and different clinico-pathological parameters, Chi-squared tests were performed (Table 1). Except for histological grade (p = 0.0008) and TNM stage (p = 0.0114), there was no correlation between RECK and most of the analyzed factors (age, menopausal status, tumor size, lymph node stage, recurrence and ER/PR status).

Table 1.

Association between RECK expression and clinicopathological parameters

| Parameter | RECK negative no. cases (%) | RECK positive no. cases (%) | χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| < 50 years | 195 (18.8 %) | 191 (18.4 %) | 0.021 | 0.8848 |

| ≥ 50 years | 324 (31.3 %) | 326 (31.5 %) | ||

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Premenopausal | 206 (20.1 %) | 197 (19.1 %) | 0.082 | 0.7752 |

| Postmenopausal | 312 (30.4 %) | 312 (30.4 %) | ||

| Tumor size | ||||

| < 5 cm | 252 (25.5 %) | 268 (27.1 %) | 1.494 | 0.2216 |

| ≥ 5 cm | 247 (24.9 %) | 223 (22.5 %) | ||

| Lymph node stage | ||||

| Negative (N0) | 169 (16.6 %) | 160 (15.7 %) | 0.243 | 0.6222 |

| Positive (N1, N2, N3) | 341 (33.5 %) | 348 (34.2 %) | ||

| Recurrence | ||||

| Negative | 257 (25.1 %) | 259 (25.3 %) | 0.063 | 0.8014 |

| Positive | 258 (25.2 %) | 250 (24.4 %) | ||

| ER/PR status | ||||

| ER+/PR+ | 208 (22.3 %) | 204 (22.0 %) | 8.001 | 0.046 |

| ER+/PR- | 125 (13.5 %) | 86 (9.3 %) | ||

| ER-/PR+ | 8 (0.9 %) | 11 (1.2 %) | ||

| ER-/PR- | 135 (14.5 %) | 151 (16.3 %) | ||

| Histological grade | ||||

| 1 | 86 (8.3 %) | 73 (7.1 %) | 14.257 | 0.0008 |

| 2 | 315 (30.5 %) | 273 (26.4 %) | ||

| 3 | 116 (11.2 %) | 170 (16.5 %) | ||

| TNM stage | ||||

| 1 | 39 (3.8 %) | 17 (1.6 %) | 11.069 | 0.0114 |

| 2A and 2B | 201 (19.5 %) | 204 (19.7 %) | ||

| 3A, 3B, and 3C | 240 (23.2 %) | 240 (23.2 %) | ||

| 4 | 39 (3.8 %) | 54 (5.2 %) | ||

χ2, Chi-square test coefficient; ER/PR, estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor

p-values considered significant after FDR correction were highlighted in bold

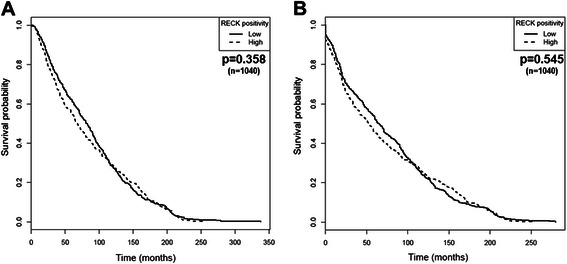

RECK is not a prognostic indicator for breast cancer patients

To determine whether RECK would be a useful marker for the survival rate or could serve as a prognostic indicator, we performed several sets of analyses. The association between RECK and the overall (OS) and disease-free (DFS) survival was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig. 4). RECK expression did not predict any significant differences in OS and DFS (Fig. 4) among all of the 1040 breast cancer cases analyzed.

Fig. 4.

RECK does not a predictive value for the survival of breast cancer patients. Differences in the overall (a) and disease-free survival (b) based on RECK immunoreactivity intensity of the diagnosed tumors were assessed using Kaplan-Meier plots

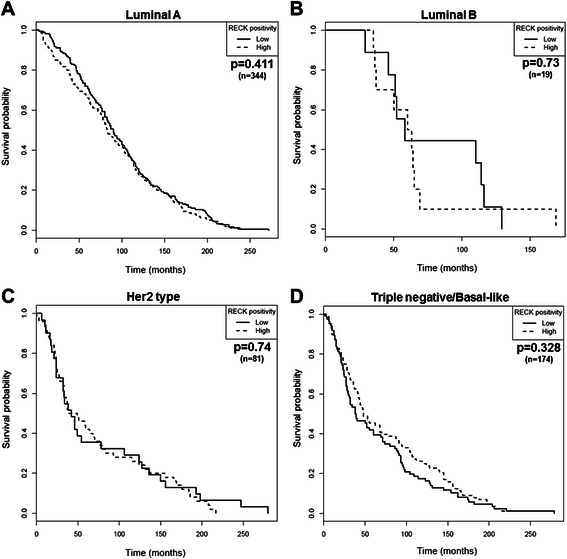

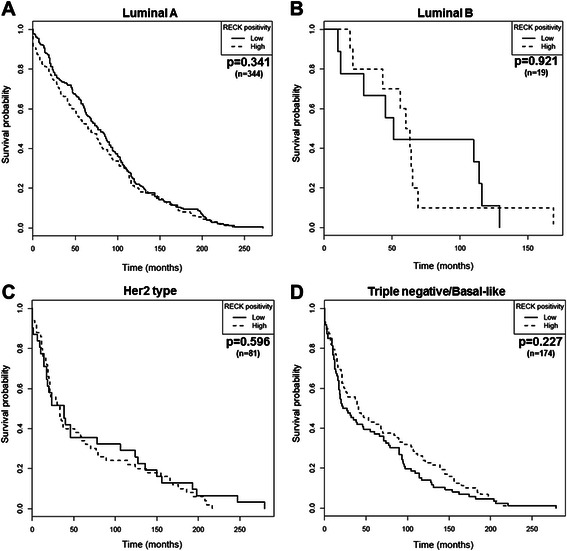

The prognostic significance of RECK for specific cohorts of patients was further evaluated. The tumor samples were classified according to molecular subtypes, namely luminal A, luminal B, Her2 type and basal-like/triple negative, which, in turn, were determined by the status of crucial breast cancer biomarkers (ER, PR and Her2). Samples were excluded from the analysis once the parameters required for subtype discrimination were not available. Thus, the predictive value of RECK was tested in 344 cases of luminal A, 19 cases of luminal B, 81 cases of Her2 type and 174 cases of Triple-negative/basal-like breast cancer. Regardless of each molecular subtype examined, differences in the RECK protein levels were not associated with significant changes in OS (Fig. 5) or DFS (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

RECK is not associated with the overall survival (OS) of breast cancer patients regardless of the molecular subtype examined. Kaplan-Meier plots were obtained for OS analysis stratified by RECK expression in patients diagnosed with (a) luminal A, (b) luminal B, (c) Her2 type and (d) basal-like breast tumors

Fig. 6.

RECK is not a prognostic marker of disease-free survival (DFS) for patients diagnosed with different breast cancer molecular subtypes. Kaplan-Meier plot estimate of DFS stratified by RECK expression in breast cancer patients diagnosed with (a) luminal A, (b) luminal B, (c) Her2 type and (d) basal-like tumors

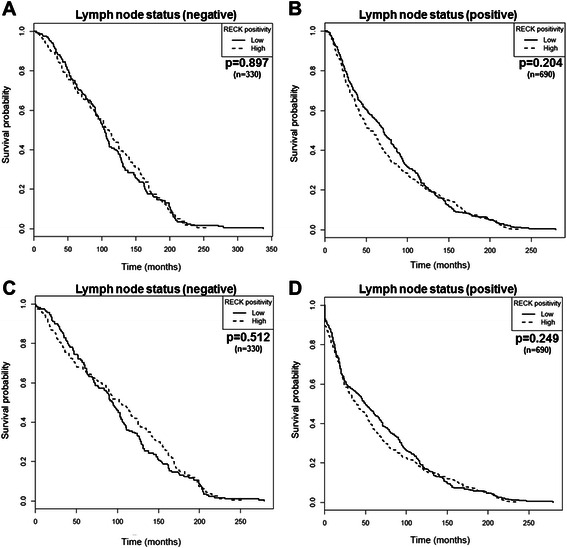

The presence of tumor cells in axillary lymph nodes is also critical for the staging and prognosis of breast cancer, in addition to providing a more assertive therapy choice. Survival analyses were also performed considering two distinct groups: lymph node-negative (n = 330) or -positive (n = 690) patients. However, independently of lymph node status, RECK remained unable to predict the OS and DFS of these patients (Fig. 7). Multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that RECK did not provide independent prognostic information for breast cancer patient survival (Tables 2 and 3), strengthening the already reported evidence that this MMP inhibitor is not a relevant biomarker for breast cancer.

Fig. 7.

RECK is not related to survival of breast cancer patients regardless of the lymph node status. Kaplan-Meier curves of overall (a and b) and disease-free (c and d) survival stratified by RECK expression in breast cancer patients classified as lymph node negative (a and c) or positive (b and d) at diagnosis

Table 2.

Cox regression for overall survival analysis in the entire patient cohort

| Entire cohort (n = 940) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariatea | |||||

| Prognostic factor | HR | 95 % CI | p-value | HR | 95 % CI | p-value |

| RECK (low vs. high) | 0.95 | 0.67–1.37 | 0.8 | 0.91 | 0.63–1.31 | 0.63 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | <0.01 | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | <0.01 |

| Tumor size (continuous) | 1.05 | 1.02–1.07 | <0.01 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.02 |

| Histological grading (3 vs. 1–2) | 1.27 | 1.14–1.40 | <0.01 | 1.24 | 1.11–1.38 | <0.01 |

| TNM stage (IV vs. I–III) | 1.05 | 0.98–1.13 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.93–1.07 | 0.96 |

| Nodal status (positive vs. negative) | 1.53 | 1.34–1.76 | <0.01 | 1.51 | 1.32–1.74 | <0.01 |

| ER (positive vs. negative) | 0.88 | 0.77–1.01 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 0.81–1.13 | 0.6 |

| PR (positive vs. negative) | 0.88 | 0.77–1.00 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.82–1.12 | 0.59 |

| Her2 (positive vs. negative) | 1.22 | 1.01–1.48 | 0.04 | 1.01 | 0.82–1.25 | 0.91 |

RECK. REversion-inducing Cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs; ER. estrogen receptor; PR. progesterone receptor; Her2. human epidermal growth factor 2

aAdjusted for all other variables in the table

Table 3.

Cox regression for disease-free survival analysis in the entire patient cohort

| Entire cohort (n = 940) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariatea | |||||

| Prognostic factor | HR | 95 % CI | p-value | HR | 95 % CI | p-value |

| RECK (low vs. high) | 0.98 | 0.69-1.38 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.64–1.31 | 0.63 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | <0.01 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | <0.01 |

| Tumor size (continuous) | 1.08 | 1.06–1.11 | <0.01 | 1.06 | 1.03–1.09 | <0.01 |

| Histological grading (3 vs. 1–2) | 1.28 | 1.16–1.42 | <0.01 | 1.26 | 1.13–1.41 | <0.01 |

| TNM stage (IV vs. I–III) | 1.13 | 1.05–1.22 | <0.01 | 1.07 | 0.99–1.14 | 0.08 |

| Nodal status (positive vs. negative) | 1.57 | 1.37–1.80 | <0.01 | 1.51 | 1.31–1.74 | <0.01 |

| ER (positive vs. negative) | 0.89 | 0.78–1.02 | 0.11 | 1.04 | 0.87–1.23 | 0.68 |

| PR (positive vs. negative) | 0.85 | 0.75–0.97 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.79–1.08 | 0.3 |

| Her2 (positive vs. negative) | 1.16 | 0.96–1.40 | 0.13 | 0.96 | 0.78–1.18 | 0.71 |

RECK. REversion-inducing Cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs; ER. estrogen receptor; PR. progesterone receptor; Her2. human epidermal growth factor 2

aAdjusted for all other variables in the table

Discussion

Since its first report, RECK down-regulation has been linked to tumor progression [15, 32], and it is considered to be an adequate biomarker for a better clinical course for patients diagnosed with various tumors [23]. Nevertheless, in this study, we obtained surprising evidence that RECK is not associated with breast cancer patient survival. Initially, our results may seem contradictory to previously published data. However, despite the extensive amount of work addressing the RECK prognostic value for prostate, lung and pancreatic tumors, RECK function and expression profile in breast cancer remain an open question. The few preceding papers on human mammary gland assessed RECK in a reduced number of samples and, in most cases, only at the transcriptional level [24–27]. Moreover, these prior studies are controversial. Some of them corroborate the typical RECK down-modulation as a hallmark of tumor aggressiveness [24, 25]. Conversely, another report demonstrated not only higher RECK levels in invasive breast cancer cell lines than in the non-invasive one but also a positive correlation between RECK and MMP expression in tumor tissue samples [26]. In the present work, we measured RECK protein levels both in a panel of human breast cell lines and in a large series (1040) of breast cancer cases, allowing a more significant conclusion.

Additionally, we performed a functional analysis of RECK in a breast cancer cell model. Despite the differential expression profile displayed by RECK in breast cancer samples, we confirmed that it performs similar functions in MDA-MB-231 cells to those previously described in other models. In this cell culture model, RECK continues to act as an invasion inhibitor via MMP down-modulation even in highly invasive human breast cancer cells. Although, at first, it may seem conflicting, we hypothesize that, to restore the balance between proteases and their inhibitors, cells respond by inducing RECK. In fact, an increase in both MMPs and TIMPs has been described as a central and crucial hallmark of tumor progression. Although this may be a mechanism to maintain the protease/inhibitor ratio in balance, this cellular response mechanism cannot block disease progression.

Conclusions

In contrast to other tumor types, RECK expression cannot predict breast cancer patient survival, although its inhibitory function in invasion has been confirmed. Despite the well-known cancer heterogeneity, several studies are still aiming to identify a universal tumor marker and draw an overall conclusion. However, in agreement with the emerging concept of personalized cancer therapy, general conclusions should be avoided, and more tumor-specific biomarkers should be sought.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Mina J. Bissell (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Life Science Division, Berkeley, CA, USA) for the supervision of all cell culture data presented in this work. We are also grateful to Dr. Bissell for important suggestions and helpful comments. We are deeply grateful for the excellent technical assistance provided by Zizi de Mendonça, Sandra Regina de Souza, Débora Cristina da Costa, Ricardo Krett de Oliveira and Marluce Mantovani. This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq), Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (FINEP), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Social e Econômico (BNDES – FUNTEC), Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia em Saúde - Ministério da Saúde (DECIT-MS) and Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação (MCTI).

Abbreviations

- CK

Cytokeratin

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- KM

Kaplan-Meier

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- OS

Overall survival

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- RECK

Reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs

- TIMP

Tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases

- TMA

Tissue microarray

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LRG was responsible for most of the experimental work, results interpretation and manuscript preparation. AF performed the statistical analysis and assisted in data interpretation. JDM and LL participated in the study design and data discussion. FAS executed the immunohistochemistry staining on TMA blocks. MCS was involved in the study design, results interpretation and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Luciana R. Gomes, Email: luciana.gomes@usp.br

André Fujita, Email: fujita@ime.usp.br.

Joni D. Mott, Email: jdmott@lbl.gov

Fernando A. Soares, Email: fasoares@me.com

Leticia Labriola, Email: labriola@iq.usp.br.

Mari C. Sogayar, Email: mcsoga@iq.usp.br

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacac M, Stamenkovic I. Metastatic cancer cell. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:221–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson N, Ahonen M, Kahari VM. Matrix metalloproteinases in tumor invasion. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57(1):5–15. doi: 10.1007/s000180050495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25(1):9–34. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-7886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radisky ES, Radisky DC. Matrix metalloproteinase-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15(2):201–212. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9177-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert E, Dasse E, Haye B, Petitfrere E. TIMPs as multifacial proteins. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;49(3):187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark JC, Thomas DM, Choong PF, Dass CR. RECK--a newly discovered inhibitor of metastasis with prognostic significance in multiple forms of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(3–4):675–683. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGowan PM, Duffy MJ. Matrix metalloproteinase expression and outcome in patients with breast cancer: analysis of a published database. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(9):1566–1572. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu D, Zhang Z, Li Y, Zheng J, Dong G, Wang W, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is associated with disease-free survival and overall survival in patients with gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(4):887–895. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dragutinovic VV, Radonjic NV, Petronijevic ND, Tatic SB, Dimitrijevic IB, Radovanovic NS, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and −9 (MMP-9) in preoperative serum as independent prognostic markers in patients with colorectal cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;355(1–2):173–178. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu ZS, Wu Q, Yang JH, Wang HQ, Ding XD, Yang F, et al. Prognostic significance of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 serum and tissue expression in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(9):2050–2056. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liss M, Sreedhar N, Keshgegian A, Sauter G, Chernick MR, Prendergast GC, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-4 is elevated in early-stage breast cancers with accelerated progression and poor clinical course. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(3):940–946. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schrohl AS, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Holten-Andersen MN, Christensen IJ, Look MP, Mouridsen HT, et al. Primary tumor levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 are predictive of resistance to chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(23):7054–7058. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy K, Maguire T, McGreal G, McDermott E, O’Higgins N, Duffy MJ. High levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 predict poor outcome in patients with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;84(1):44–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990219)84:1<44::AID-IJC9>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi C, Sheng Z, Horan TP, Kitayama H, Maki M, Hitomi K, et al. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and inhibition of tumor invasion by the membrane-anchored glycoprotein RECK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(22):13221–13226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noda M, Oh J, Takahashi R, Kondo S, Kitayama H, Takahashi C. RECK: a novel suppressor of malignancy linking oncogenic signaling to extracellular matrix remodeling. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22(2–3):167–175. doi: 10.1023/A:1023043315031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh J, Takahashi R, Kondo S, Mizoguchi A, Adachi E, Sasahara RM, et al. The membrane-anchored MMP inhibitor RECK is a key regulator of extracellular matrix integrity and angiogenesis. Cell. 2001;107(6):789–800. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takagi S, Simizu S, Osada H. RECK negatively regulates matrix metalloproteinase-9 transcription. Cancer Res. 2009;69(4):1502–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masui T, Doi R, Koshiba T, Fujimoto K, Tsuji S, Nakajima S, et al. RECK expression in pancreatic cancer: its correlation with lower invasiveness and better prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(5):1779–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furumoto K, Arii S, Mori A, Furuyama H, Gorrin Rivas MJ, Nakao T, et al. RECK gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation with invasion-related clinicopathological factors and its clinical significance. Reverse-inducing--cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs. Hepatology. 2001;33(1):189–195. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takemoto N, Tada M, Hida Y, Asano T, Cheng S, Kuramae T, et al. Low expression of reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs (RECK) indicates a shorter survival after resection in patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2007;58(3):376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeuchi T, Hisanaga M, Nagao M, Ikeda N, Fujii H, Koyama F, et al. The membrane-anchored matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) regulator RECK in combination with MMP-9 serves as an informative prognostic indicator for colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(16):5572–5579. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noda M, Takahashi C. Recklessness as a hallmark of aggressive cancer. Cancer Sci. 2007;98(11):1659–1665. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Cheng S, Zhang G, Ma W, Liu Y, Zhao R, et al. Low expression of RECK indicates a shorter survival for patients with invasive breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(6):1084–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Span PN, Sweep CG, Manders P, Beex LV, Leppert D, Lindberg RL. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs: a prognostic marker for good clinical outcome in human breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2710–2715. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Figueira RC, Gomes LR, Neto JS, Silva FC, Silva ID, Sogayar MC. Correlation between MMPs and their inhibitors in breast cancer tumor tissue specimens and in cell lines with different metastatic potential. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong KJ, Hsu MC, Hou MF, Hung WC. The tumor suppressor RECK interferes with HER-2/Neu dimerization and attenuates its oncogenic signaling. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(4):591–595. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Australia: the R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2012, ISBN 3-900051-07-0

- 30.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc. Series B (Methodological). 1995;57(1):289–300.

- 31.Nagini S. RECKing MMP: relevance of reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs as a prognostic marker and therapeutic target for cancer (a review) Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12(7):718–725. doi: 10.2174/187152012802650237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasahara RM, Takahashi C, Sogayar MC, Noda M. Oncogene-mediated downregulation of RECK, a novel transformation suppressor gene. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1999;32(7):891–895. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X1999000700014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simizu S, Takagi S, Tamura Y, Osada H. RECK-mediated suppression of tumor cell invasion is regulated by glycosylation in human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 2005;65(16):7455–7461. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]