Summary

Increasing evidence supports an association between obstructive sleep apnoea and metabolic syndrome in both children and adults suggesting a genetic component. However, the genetic relationship between the diseases remains unclear.

We performed a bivariate linkage scan on a single Filipino family with a high prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea and metabolic syndrome to explore the genetic pathways underlying these diseases. A large rural family (N=50, 50% adults) underwent a 10cM genome-wide scan. Fasting blood was used to measure insulin, triglycerides, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol. Attended overnight polysomnography was used to quantify the respiratory disturbance index (RDI), a measure of sleep apnea. BMI z-scores and insulin resistance scores were calculated. Bivariate multipoint linkage analyses were performed on RDI and metabolic syndrome components.

Obstructive sleep apnea prevalence was 46% (n=23; 9 adults, 14 children) in our participants. Metabolic syndrome phenotype was present in 40% of adults (n=10) and 48% of children (n=12). Linkage peaks with a LOD score > 3 were demonstrated on chromosome 19q13·4 (LOD=3·04) for the trait pair RDI and high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Candidate genes identified in this region include the killer-like immunoglobulin receptor (KIR) genes. These genes are associated with modulating inflammatory responses in reaction to cellular stress and initiation of atherosclerotic plaque formation. We have identified a novel locus for genetic links between RDI and lipid factors associated with metabolic syndrome in a chromosomal region containing genes associated with inflammatory responses.

Keywords: bivariate, metabolic syndrome, obesity, respiratory disturbance index, inflammation, gene

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is characterised by repetitive episodes of upper airway obstruction that occur during sleep, usually associated with a reduction in blood oxygen saturation (AASM, 2001). It is hypothesized that the ensuing repetitive cycles of intermittent hypercapnia and hypoxia, lead to sympathetic nervous activation, instigating metabolic dysfunction and an increased risk for developing obesity, type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in later life (Lavie, 2003, Srinivasan et al., 2006). Prevalence of OSA in Asian populations is between 2-4% and is similar to that reported for Caucasian populations (Villaneuva et al., 2005; Lam et al., 2007). However, the BMI values associated with increased risk for developing OSA and associated complications are lower in Asian than Caucasian populations (Villaneuva et al., 2005).

The metabolic dysfunction associated with OSA is identical to the clustering of metabolic factors observed in the metabolic syndrome (MeS), namely dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and obesity (de la Eva et al., 2002; Ip et al., 2002; Coughlin et al., 2004; Sasanabe et al., 2006; Kono et al., 2007; McArdle., et al., 2007; Peled et. al., 2007; Redline et al., 2007; Morales et al., 2008). It is estimated that MeS is present in 18.6% of Filipino adults (Morales et al., 2008).

Longitudinal studies, such as the Bogalusa Heart Study, have tracked components of the metabolic syndrome separately from childhood and found an increased risk of developing CVD in later life (Srinivasan et al., 2006). The link between OSA and MeS has been established in adult, paediatric and animal studies (de la Eva et al., 2002; Ip et al., 2002; Coughlin et al., 2004; Sasanabe et al., 2006; McArdle et al., 2007; Peled et. al., 2007; Waters et al., 2007; Nock et al., 2009). Although obesity is a frequent confounder, studies have also shown that non-obese individuals with OSA have a greater number of MeS components than non-obese individuals without OSA (Kono et al., 2007; Peled et al., 2007; Redline et al., 2007).

Increasing evidence supports an association between OSA and components of MeS in both children and adults (de la Eva et al., 2002; Coughlin et al., 2004; Ng et al., 2004; Sasanabe et al., 2006; Tam et al., 2006; Kono et al., 2007; Peled et al., 2007; Redline et al., 2007; Morales et al., 2008; Nock et al., 2009), suggesting a genetic component, and one that begins in childhood.

Previous genome-wide scans have examined links for sleep apnoea alone or metabolic syndrome and associated metabolic factors (Loos et al., 2003; Palmer et al., 2003; Ng et al., 2004; Palmer et al., 2004; Larkin et al., 2008). While these studies have identified candidate regions, genetic loci that are conclusively associated with OSA and MeS remain elusive. Also, despite recognition of the importance of OSA as a comorbidity with obesity, there is a paucity of genetic studies at all levels, which contrasts to the plethora of studies for obesity co-morbidities such as MeS and type II diabetes.

This study is the first bivariate genetic analysis to incorporate both sleep apnoea and related metabolic syndrome traits.

In this study we have investigated potential genetic loci that may harbour genes influencing OSA and its associated metabolic components. We undertook a 10cM genome wide scan in a large single Filipino family with a history of snoring and diabetes. Examining such an extensive family was possible in the Philippines where, compared with most other Asian countries, demographic transition has been extremely slow. To test our hypothesis, bivariate multipoint linkage analyses were performed on the respiratory disturbance index as the main metric of OSA, and components of the MeS to identify associated susceptibility loci.

Material and Methods

A large extended Filipino family with a history of snoring, diabetes mellitus and obesity was ascertained through a child index case with laboratory diagnosed OSA in Sydney, Australia. Fifty family members, spanning four generations, consented to participate in the study. Approval for this study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia.

Sleep Studies

Attended overnight polysomnography was performed on 43 members of the family in rural Philippines, using a portable sleep machine (Compumedics E series, Abbotsford Victoria), operated by trained sleep technicians at an off-site rental location. The remaining seven family members attended Westmead Hospital and The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Australia for overnight polysomnography and phenotyping. The presence and severity of obstructive sleep apnoea was quantified by the respiratory disturbance index (RDI), defined as the number of apnoeas plus hypopneas with ≥3% SaO2 desaturation or arousal per hour of sleep.

Definition of RDI and Severity of Sleep Apnea

In adults the following RDI categories were used to define OSA severity; unaffected, RDI < 5, mild OSA = RDI ≥ 5 but < 10, moderate OSA = RDI ≥ 10 but < 20 and severe OSA = RDI ≥ 20. In children, an RDI ≤ 1 was scored as unaffected, ≥1 but < 5 = mild OSA, ≥ 6 but <10 = moderate OSA and ≥10 = severe OSA.

Anthropometric measurements

Height (cm) and weight (kg), waist circumference (cm) were measured directly from consenting family members. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2) and adjusted for age and sex as BMI-z using the CDC 2000 growth references (http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/). Adult BMI-Z was calculated using the 18 year old value from the CDC 2000.

Sample Collection and Processing

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture on the morning after completion of the sleep study after overnight fasting. Whole blood was collected for DNA analysis and stored at room temperature. Total cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, glucose, and insulin were determined from frozen plasma samples. All samples were shipped to Australia every three days over the 3 week period of data collection for analysis. In cases where sufficient blood could not be drawn for DNA analysis, a buccal swab (Buccal Amp Kit, Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA) was collected, stored at 4°C and shipped to Australia for DNA extraction.

Biochemical and Endocrinological Studies

Levels of plasma insulin, cholesterol, glucose levels, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol were determined as previously described (de la Eva et al., 2002). Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the following formula: [fasting insulin (μU/ml) x fasting glucose (mM)]/22·5 and used as a measure of insulin resistance.

Genetic Studies

Whole blood was obtained from all consenting family members for DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood using methods described by Sambrook and Russell (2001), with minor modifications. When needed, DNA was extracted from buccal scrapings using the BuccalAmp kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA).

A whole genome wide scan was performed by the Australian Genome Research Facility (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) using approximately 400 microsatellite markers, spaced at an average genetic distance of 10cM.

Definition of the metabolic syndrome

Adult definition

Modified WHO criteria were used to define MeS in adults including WHO Asian BMI cut-offs of 18-23 = normal, >23 = overweight, >25 = obese, where waist circumference measurements were not available (WHO 1999; WHO Expert Consultation, 2004). Additional information is available in the online supplement.

Paediatric definition

As there is no consensus on the definition of MeS in children, different criteria were required than those used for adults. The cut-points in the definition of MeS risk as used by Lambert et al., (2004) were used to classify the paediatric subjects for this study. Additional information is available in the online supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Exclusion of participants for medication effects was not necessary in this study. Limited access to medical services precluded treatment. To achieve normal distribution of variables, HOMA, HDL cholesterol, triglyceride and cholesterol values were natural log transformed. RDI values were natural log +1 transformed to overcome distribution and skewness problems.

Relationship and marker error checking were conducted in the S.A.G.E. package (S.A.G.E., 2007). Multipoint identity by descent (IBD) allele sharing was calculated using the LOKI software for large pedigrees. LOKI uses Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation to estimate the allele sharing, based on allele frequency estimated from SOLAR which models the genetic covariances between relative pairs as a function of IBD allele sharing at a genetic marker. This approach models the phenotypic variance within pedigrees as a function of the additive genetic variance (due to a linked underlying quantitative trait locus ), a polygenic variance and environmental variance , while allowing for simultaneous adjustment of covariates including age, sex and age2. The variance covariance-matrix for a pedigree of arbitrary size using an additive only model results can be written as:

| (0.1) |

where Π is a matrix whose elements (πij) provide the proportion of alleles that individuals j and i share IBD at a QTL, I is an identity matrix incorporating random error for each individual and 2Φ represents the matrix of kinship coefficients. By assuming multivariate normality within a pedigree, a likelihood can be written out and computed. A test for linkage of the additive genetic variance due to the lth QTL is conducted by comparing the likelihood of a model in which a non-negative is estimated to a restricted model without estimated (Almasy and Blangero, 1998). A LOD score, similar to model based linkage analyses, is calculated by taking the log of the ratio of the likelihood models under the alternative hypothesis of linkage and no linkage.

Using ⊗ to denote a Kronecker product, the pedigree based variance component approach can be extended easily to analyze bivariate phenotypes by redefining the variance matrix:

| (0.2) |

In the bivariate case, the matrix M is a 2 by 2 variance covariance matrix due to the additive effect of a QTL, P is the additive polygenic variance covariance matrix and E is the environmental variance covariance matrix (Almasy et al., 1997). The covariance between 2 individuals for two traits x and y can be written in the following form:

| (0.3) |

| (0.4) |

This formulation includes parameters for the genetic and environmental correlation between the traits for pairs of relatives in pedigrees of arbitrary size. These terms are ρl, which represents the shared correlation of the two traits of interest due to the putative locus; ρg, which represents additional residual genetic correlation unrelated to the QTL; and ρe ,which represents environmental correlation. It is noted that that if trait x and trait y are identical, the genetic correlation ρg is 1 and the above equation reduces to univariate linkage analysis (Martin et al., 2004). As with the univariate case, a bivariate LOD score can be calculated and converted to a univariate LOD equivalent (Amos et al., 2001).

Because the parameter estimates and the standard errors computed by SOLAR for the genetic and environmental correlation parameters were large or on the boundary of 1, the FCOR procedure of S.A.G.E. was used to estimate the overall phenotypic correlation on the trait residuals after pre-adjusting for covariates using linear regression.

A likelihood ratio test of complete pleiotropy was conducted by comparing models in which ρg is constrained to 1 versus a model in which it is estimated, assume twice the difference of the log likelihoods is distributed as a 50:50 mixture of a χ2 distribution with 1 degree of freedom and a point mass at 0 (Almasy and Blangero, 1998). A test of co-incident linkage, compares models is which ρg is freely estimated and ρl is constrained to 0, where there are no shared genetic effects. This likelihood ratio test statistic is asymptotically distributed under the null hypothesis as chi-square with 1 degree of freedom (Almasy et al., 1997).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Family

Our family comprised 50 individuals (adult n=25; male n=26) over 4 generations, residing in the rural Philippines (n=43) and Sydney, Australia (n=7). General, clinical and metabolic characteristics of the family are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

General and Clinical Characteristics of the study family

| Adults | Children (<18yrs) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| Male/Female | 12/13 | 14/11 | 26/24 |

| Age (years) | 42·6 ± 15·29 | 11·0 ± 3·76 | 27·6 ± 19·4 |

| BMI (adults;kg/m2)/BMI-z (children) | 25·2 ± 4.9 | 0·08± 1.77 | |

| Waist circumference (cm), (n) | 85.6 (18) | 65.7 (9) | 79 (27) |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5·31 ± 1·07 | 3·88 ± 0·75 | 4·60±1·16 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1·03±0·27 | 1·12±0·26 | 1·07±0·27 |

| Triglycerides (TG) (mmol/L) | 2·09±1·37 | 1·00±0·47 | 1·55±1·16 |

| Fasting Insulin (pmol/L) | 132± 120·5 | 91·64±71·50 | 112·03±100·20 |

| Fasting Plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 5·85±1·84 | 4·50±0·42 | 5·17±1·49 |

| HOMA-IR | 5·96±5·76 | 3·13±2·59 | 4·54±4·65 |

| n (% ) low HDL-C | 11 (44) | 17 (68) | 28 (56) |

| n (%) high triglycerides | 11 (44) | 13 (52) | 24 (48) |

| % high insulin | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| n (%) hyperglycaemic/diabetic | 4 (16) | 0 | 4 (8) |

| RDI (events/hr) | 7·1±9·0 | 3·0±7·8 | 5·1±8·5 |

| OSA, n (%) | 9 (36) | 14 (56) | 23 (46) |

| -Mild OSA, n (%)* | 3 (12) | 10 (40) | 13 (26) |

| -Moderate OSA, n (%)# | 2 (8) | 3 (12) | 5 (10) |

| -Severe OSA, n (%)^ | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 5 (10) |

| MeS, n (%) | 10 (40) | 12 (48) | 22 (44) |

| OSA and MeS, n (%) | 7 (28) | 6 (24) | 13 (26) |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI-z – body mass index z score; HDL–high density lipoprotein cholesterol; RDI – respiratory disturbance index; OSA– obstructive sleep apnea; MeS–metabolic syndrome; TG–triglycerides.

Values are mean ± standard deviation (SD)

Adult: RDI ≥ 5 but < 10; Child: RDI ≥1 but < 5.

Adult: RDI ≥ 10 but < 20 ; Child RDI ≥ 6 but <10.

Adult: RDI ≥ 20; Child: RDI ≥ 10.

Obstructive Sleep Apnoea

The prevalence of OSA in our family was 46%: 9 adults and 14 children were diagnosed with OSA (Table 1). The majority of adults and children with OSA had mild or moderate disease (Table 1). Mild sleep apnoea (Adults: RDI ≥ 5 but < 10; Children: RDI ≥1 but < 5) was diagnosed in 13 family members (3 adult and 10 children), moderate OSA (Adults: RDI ≥ 10 but < 20; Children: RDI ≥ 6 but <10 ) in five members (2 adults and 3 children) and severe OSA (Adults: RDI ≥ 20; Children: RDI ≥10) in five members (4 adults and 1 child).

Metabolic characteristics

On average, adults were obese (mean BMI 25·2kg/m2), but not children (mean BMI-Z score = 0·08). MeS disease risk cluster phenotype was present in 40% of adults (n=10) and 48% of children (n=12). Four adults had type 2 diabetes. A high prevalence of dyslipidemia was also apparent in our family. Hypertriglyceridemia was present in 44% of adults and 52% of children. Low HDL-C was found in 44% of adults and 68% of children. All adults had elevated fasting plasma insulin values and 48% were insulin resistant.

A high prevalence of metabolic disturbances was seen in the children. High triglyceride levels were present in 48% of children and 68% had low HDL-C values. All children were hyperinsulinaemic. Two or more MeS risk factors were present in 12 (48%) children.

Univariate Linkage Results

No evidence of genome wide linkage was observed from the univariate analyses. Regions suggestive on linkage were identified on chromosome 7 and 2. (See Figure E1 in the online supplement). Additional results are presented in the online supplement.

Bivariate Linkage Results

Pairwise relationships are presented in Table 2. Genetic, phenotypic and environmental correlations between traits are presented in Table 3. Genetic correlations between RDI and each of BMI-z, TG and HOMA, indicated strongly shared genetic effects amongst these traits. For RDI/HOMA and RDI/ BMI-Z genetic correlations were estimated to be 1, and for RDI/HDL −0.004. However, standard errors for these trait pairs were very large.

Table 2.

Pairwise relationship of family member (n=50).

| Relationship | No. of pairs |

|---|---|

| Parent-offspring | 60 |

| Full Siblings | 79 |

| Half Siblings | 4 |

| Grandparent | 37 |

| Avuncular | 160 |

| First Cousins | 223 |

| Mother-father | 6 |

| TOTAL | 569 |

Table 3.

Genotypic, phenotypic and environmental correlations for bivariate traits analysis.

| Traits | Genetic correlation | Environmental correlation | Phenotype correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDI/BMI-z | 1 (at bound) | 0·21 (0·25) | 0·56 (0·13) |

| RDI/HDL | −0·004 (0·54) | −0·28 (0·23) | −0·10 (0·22) |

| RDI/CHOL | 0·17 (0·39) | 0·65 (0·14) | 0·40 (0·17) |

| RDI/TG | 0·78 (0·46) | 0·26 (0·20) | 0·46 (0·13) |

| RDI/HOMA | 1 (at bound) | 0·02 (0·20) | 0·37 (0·15) |

All traits were adjusted for age, age2 and sex. Value in parentheses are standard error of mean.

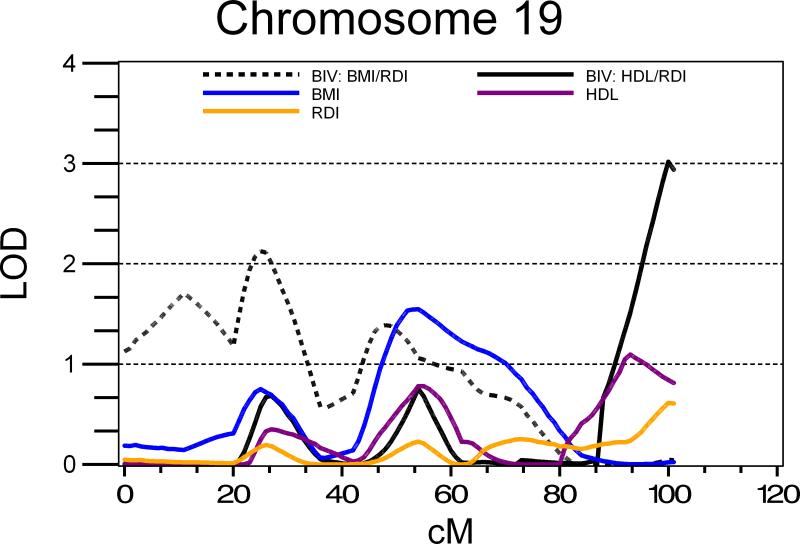

Evidence for genome-wide linkage was observed on chromosome 19, region 19q13·4 at 100cM for the trait pair RDI/HDL cholesterol (LOD=3·04; Figure 1). For traits RDI/HDL on chromosome 19, tests for coincident linkage and complete pleiotropy were inconclusive. Evidence suggestive of linkage for RDI/HDL was also observed on chromosome 7 (7q34; 157cM; LOD = 2·15; Table 4).

Figure 1.

Univariate and bivariate multipoint linkage analysis results for chromosome 19.

Definition of abbreviations: BIV-bivariate; BMI-body mass index z score; HDL-high density lipoprotein cholesterol; RDI-respiratory disturbance index.

All traits were adjusted for age, age2 and sex.

Table 4.

Multipoint LOD scores >2 and candidate genes from bivariate linkage analysis for different trait pairs.

| Trait | Chromosome Location | cM | Bivariate LOD | Candidate Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDI/HDL | 19q13·4 | 100 | 3·04 | Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, two domains, long cytoplasmic tail, 4 (KIR2DL4) Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, three domains, long cytoplasmic tail, 1 (KIR3DL1) |

| RDI/HDL | 7q34 | 157 | 2·15 | Thromboxane A synthase 1 (TBXAS1) Insulin-induced protein 1 (INSIG1) |

| RDI/BMI-z | 19p13·2 | 25 | 2·12 | Insulin receptor (INSR) Intercellular adhesion molecule 1, human rhinovirus receptor (ICAM1) Tyrosine kinase (TYK2) Calcium channel, voltage dependent P/Q type, alpha 1A subunit (CACNA1A) |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI-z – body mass index Z score; HDL–high density lipoprotein, RDI – respiratory disturbance index.

Evidence suggestive of linkage was observed on chromosome 19 at 19p13·2, (25cM; LOD=2·12) for the trait pair RDI/BMI-z (Figure 1; Table 4).

Discussion

Our study family, with a high prevalence of OSA, insulin resistance and type II diabetes, was chosen to increase the power of identifying loci associated with OSA and MeS. We are the first to report evidence of a novel quantitative trait loci (QTL) for OSA on chromosome 19q13·4, (LOD score of 3·04), for the traits RDI and HDL. This study, is to our knowledge, the only published study conducted investigating bivariate linkage analyses of RDI with traits of adiposity, obesity and insulin resistance that has included children as well as adults in the analysis. It is the first study to present multivariate linkage results for RDI and the first linkage study for these traits in Filipinos.

Univariate multipoint variance component analysis only identified nominal regions associated with RDI. Our univariate linkage results did not replicate those of Palmer's studies in African Americans (Palmer et al., 2003; Palmer et al., 2004), or Larkin's study (Larkin et al., 2008). Several regions with over lapping linkage peaks were noted for the traits we examined so we undertook to perform a bivariate multipoint linkage analysis to investigate potential pleiotropic gene effects.

Identification of loci associated with OSA has been complicated by shared genetic effects known to exist between OSA and obesity (Palmer et al., 2003; Palmer et al., 2004; Patel, 2005; Larkin et al., 2008). Genomic studies using traits associated with low or intermediate level phenotypes of OSA may aid in identifying candidate genetic loci. We were interested in examining the trait combinations of RDI with various components of the metabolic syndrome to identify genetic regions influencing both diseases’. To investigate this we undertook a bivariate genome-wide linkage analysis.

Bivariate analyses indicated genetic correlations existed between RDI and selected metabolic trait variables in our family. RDI/HDL had a very small negative genetic correlation of −0·004 in our study, but large standard errors around the zero points estimated, and although these traits were not heritable overall they may be heritable at any specific locus. Our family lived in a remote region of the Philippines with limited access to medical care. At the time of our study none of the consenting family members were taking medications. Genetic correlations between trait pairs RDI/BMI-Z and RDI/HOMA was 1, suggesting that the underlying genes for these traits were identical in our family, i.e. there were pleiotropic gene effects. Although we hoped to establish if there were pleiotropic gene effects acting in our family, our tests were inconclusive. The failure to reject tests for both pleiotropy and coincident linkage is not conclusive proof of lack pleiotropy. As described by Almasy et al., (1997), if linkage disequilibrium is present between the underlying genes associated with the traits, this will affect the power to reject the hypothesis of complete pleiotropy. Conversely, if the proposed major gene is affected by epistatic interactions or gene x environment interaction affecting one of the correlated traits more than the other, the power to reject the hypothesis of co-incident linkage may be reduced. A similar situation would occur if major gene haplotype variations between individuals affected correlated traits differentially. Even with genetic correlations close to 1 which suggest complete pleiotropy, the large variability in our SE estimates for genetic correlation enable us to observe increased evidence for linkage of two traits at a particular locus. However we are not able to tease apart complete pleiotropy and coincident linkage.

Our linkage peak at 19q13 replicates results from several previous linkage studies. Genome wide linkage studies investigating apnoea-hypopnoea index (adjusted for BMI) performed on European Americans (Palmer et al., 2003; Larkin et al., 2006) in the Cleveland Family Study reported nominal linkage on 19q13 which was 25 cM proximal to our peak. Our study replicated QTL identified for HDL in Hong Kong Chinese by Ng et al., (2004), but again the LOD score at this peak was nominal. Linkage to 19q13·4 has also been previously reported by other groups for obesity, MeS, type II diabetes, insulin and lipid traits (Elbein and Hasstedt, 2002; Saar et al., 2003; van Tilburg et al., 2003; Bell et al., 2004; An et al., 2005; Chiu et al., 2005; Malhotra et al., 2007).

At our linkage peak at 19q13·4 the candidate genes are located within the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) gene cluster for the trait pair RDI and HDL. The KIR genes are biologically plausible candidate genes for association with OSA, despite no previous identification as candidate genes in genome-wide linkage studies (Palmer et al., 2003; Palmer et al., 2004; Larkin et al., 2008), genome-wide association studies (Gottlieb et al., 2007) studies or gene expression studies (Khalyfa et al., 2008). The KIR gene cluster, comprising 17 genes and pseudo-genes, is part of the 1Mb leukocyte receptor cluster (LRC) (Kelley et al., 2005). KIRs vary both in the number of receptors expressed on a cell, as well as allelic polymorphisms, and individuals exhibit highly haplotypic diversity due to both gene content and allelic polymorphisms (Trowsdale et al., 2001; Uhrberg et al., 2001; Kelley et al., 2005). KIR genes are expressed on natural killer (NK) and some T cells. These cell receptors, ligands for MHC class 1 and related molecules, inhibit or activate the NK cell mediated cytotoxicity pathway in response to cellular stress, modulating immune responses through the release of cytokines such as TNF alpha and IL-1 (Trowsdale et al., 2001; Kelley et al., 2005). Of interest are KIR2DL4 and KIR3DL1 (NKB1).

KIR3DL1 is an inhibitory receptor expressed on both NK and T lymphocytes. T lymphocytes of OSA patients exhibit higher cell surface expression of KIR3DL1, higher intracellular levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and a concomitant decrease in cellular anti-inflammatory cytokines compared to controls (Dyugovskaya et al., 2003, 2005). Treatment with nasal CPAP reduces the cellular expression of these receptors. KIR2DL4 is both an inhibitory and stimulatory receptor. Less is known about the expression of KIR2DL4 in T-lymphocytes, but expression of this receptor has been shown to be restricted to a subset of NK cells (Jacobs et al., 2003) responsible for initiating initial interactions with vascular endothelium, establishing the linkage between OSA and atherosclerosis (Dyugovskaya et al., 2003).

Evidence is accumulating that inflammatory responses to intermittent hypoxia/hypercapnia may underlie the link between OSA and MeS, and that this process may begin in early childhood (Larkin et al, 2005; Tam et al., 2006; Gozal et al., 2008; Khalyfa et al., 2008). Several mechanistic pathways have been proposed to explain the increased risk of developing CVD in OSA patients. One of these involves the role of oxidative stress on the secretion of pro inflammatory cytokines. Production of reactive oxygen species has been reported in OSA patients and is a form of cellular stress (Dyugovskaya et al., 2003). Our linkage results support the notion suggesting of an underlying genetic susceptibility to OSA and its metabolic sequelae in at least a subgroup of individuals.

It is highly possible that the genetic association we identified is associated more with the development of obesity and type II diabetes than with loci associated with a genetic predisposition to OSA and MeS. Filipino women are genetically pre-disposed to low HDL-C value (Araneta et al., 2002; Morales et al., 2008), and normal weight normoglycemic Filipino women exhibit lower levels of adopnectin and ghrelin compared to their Caucasian counterparts (Araneta et al., 2007). However, many of the linkage peaks we observed were increased in the bivariate analysis, suggesting that regions within the genome have shared genetic effects for OSA and components of the metabolic syndrome, that are important for the development of these diseases in our Filipino family.

Limitations of our study include the use of a portable sleep machine, the absence of blood pressure and incomplete waist, neck and abdomen measurements in the adults. These missing data are a direct result of the practicalities of performing extensive studies over a three week period in the rural Philippines. Measures of fasting glucose and fasting insulin showed such skewed distribution they could not be transformed to allow us to examine these traits in our genome wide scan. Finally, factor analysis was not possible because our total subject numbers were too small. In children, small changes from normal may not been sufficiently manifest to detect genetic loci associated with the traits.

However, the strengths of the study include novel characteristics of a very large, four generation family, including a large number of children and with relatively limited prior exposure to medical attention. Those strengths are clearly illustrated by the novel genetic associations we were able to identify.

In conclusion, we have identified a novel locus for OSA in a chromosomal region containing several candidate genes associated with inflammatory responses. Genetic effects were shared between BMI and RDI, but novel genetic links were identified between RDI and lipid factors, such as HDL-C, where only independent associations had been previously identified. Further fine mapping and candidate gene studies will be necessary within our family to evaluate if the candidate genes are associated with OSA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rose White for performing the DNA extractions and Sherryn Bailey for monitoring and scoring the sleep studies. Funding source: NHLBL HL070784 (KAW) NHMRC 249403 (KAW) NIH:KL2-RR024990 (EKL)

Abbreviations

- QTL

quantitative trait loci

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- LOD

logarithm of odds

References

- Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasy L, Dyer TD, Blangero J. Bivariate quantitative trait linkage analysis: Pleiotropy versus co-incident linkages. Genet. Epidem. 1997;14:953–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1997)14:6<953::AID-GEPI65>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine . ICSD-International classification of sleep disorders, revised:Diagnostic and coding manual. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Amos C, de Andrade M, Zhu D. Comparison of multivariate tests for genetic linkage. Human Heredity. 2001;51:133–44. doi: 10.1159/000053334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araneta MR, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E. Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in Filipina-American women: a high-risk nonobese population. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:494–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An P, Freedman BI, Hanis CL, et al. Genome-wide linkage scans for fasting glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Blood Pressure Program: evidence of linkages to chromosome 7q36 and 19q13 from meta-analysis. Diabetes. 2005;54:909–14. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araneta MR, Barrett-Connor E. Adiponectin and ghrelin levels and body size in normoglycemic Filipino, African-American, and white women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2454–62. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CG, Benzinou M, Siddiq A, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis for severe obesity in French Caucasians finds significant susceptibility locus on chromosome 19q. Diabetes. 2004;53:1857–65. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu YF, Chuang LM, Hsiao CF, et al. An autosomal genome-wide scan for loci linked to pre-diabetic phenotypes in nondiabetic Chinese subjects from the Stanford Asia-Pacific Program of Hypertension and Insulin Resistance Family Study. Diabetes. 2005;54:1200–06. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SR, Mawdsley L, Mugarza JA, Calverley PM, Wilding JP. Obstructive sleep apnea is independently associated with an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Eur. Heart. J. 2004;25:735–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyugovskaya L, Lavie P, Lavie L. Phenotypic and functional characterization of blood δγ T cells in sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:242–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1226OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyugovskaya L, Lavie P, Hirsh M, Lavie L. Activated CD8+ T lymphocytes in obstructive sleep apnea. Eur. Resp. J. 2005;25:820–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00103204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbein SC, Hasstedt SJ. Quantitative trait linkage analysis of lipid-related traits in familial type 2 diabetes: evidence for linkage of triglyceride levels to chromosome 19q. Diabetes. 2002;51:528–35. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Eva RC, Baur LA, Donaghue KC, Waters KA. Metabolic correlates with obstructive sleep apnea in obese subjects. J. Pediatr. 2002;140:654–9. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.123765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb DJ, O'Connor GT, Wilk JB. Genome-wide association of sleep and circadian phenotypes. BMC Med. Genet. 2007;8(Supplement 1):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D, Serpero LD, Sans Capdevila O, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Systemic inflammation in non-obese children with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2008;9:254–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip MS, Lam B, Ng MM, Lam WK, Tsang KW, Lam KS. Obstructive sleep apnea is independently associated with insulin resistance. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;165:670–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.5.2103001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs R, Hintzen G, Kemper A, et al. CD56 bright cells differ in their KIR repertoire and cytotoxic features from CD56dim NK cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:3121–7. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<3121::aid-immu3121>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley J, Walter L, Trowsdale J. Comparative genomics of natural killer cell receptor gene clusters. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalyfa A, Capdevila OS, Buazza MO, Serpero LD, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Gozal D. Genome-wide gene expression profiling in children with non-obese obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.11.006. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono M, Tatsumi K, Saibara T, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is associated with some components of metabolic syndrome. Chest. 2007;131:1387–92. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam B, Lam DC, Ip MS. Obstructive sleep apnea in Asia. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2007;11:2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M, Paradis G, O'Loughlin J, Delvin EE, Hanley JA, Levy E. Insulin resistance syndrome in a representative sample of children and adolescents from Quebec. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2004;28:833–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin EK, Rosen CL, Kirchner HL, et al. Variation of C-reactive protein levels in adolescents: association with sleep disordered breathing and sleep duration. Circulation. 2005;111:1978–84. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161819.76138.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin EK, Patel SR, Redline S, Mignot E, Elston RC, Hallmayer J. Apolipoprotein E and obstructive sleep apnea: evaluating whether a candidate gene explains a linkage peak. Genet. Epidemiol. 2006;30:101–10. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin EK, Patel SR, Elston RC, Gary-McGuire C, Zhu X, Redline S. Using linkage analysis to identify quantitative trait loci for sleep apnea in relationship to body mass index. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2008;72:762–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00472.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie L. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome- an oxidative stress disorder. Sleep Med. Rev. 2003;7:35–51. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos RJ, Katzmarzyk PT, Rao DC, et al. HERITAGE Family Study. Genome-wide linkage scan for the metabolic syndrome in the HERITAGE family study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:5935–43. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A, Elbein SC, Ng MC, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies of quantitative lipid traits in families ascertained for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:890–6. doi: 10.2337/db06-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L, Cianflone K, Zakarian R, et al. Bivariate linkage between acylation-stimulating protein and BMI and high-density lipoproteins. Obesity Research. 2004;12:669–78. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle N, Hillman D, Beilin L, Watts G. Metabolic risk factors for vascular disease in obstructive sleep apnea: a matched control study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007;175:190–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-270OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales DD, Punzalan FE, Paz-Pacheco E, Sy RG, Duante CA, the Natioanl Nutrition and Health Survey: 2003 Group Metabolic syndrome in the Philippine general population: prevalence and risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 2008;5:36–43. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2008.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock NL, Li L, Larkin EK, Patel SR, Redline S. Empirical evidence for “syndrome Z”: a hierarchical 5-factor model of the metabolic syndrome incorporating sleep disturbance measures. Sleep. 32:615–22. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.5.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng MC, So WY, Lam VK, et al. Genome-wide scan for metabolic syndrome and related quantitative traits in Hong Kong Chinese and confirmation of a susceptibility locus on chromosome 1q21-q25. Diabetes. 2004;53:2676–83. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LJ, Buxbaum SG, Larkin EK, et al. A whole-genome wide scan for obstructive sleep apnea and obesity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:340–50. doi: 10.1086/346064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LJ, Buxbaum SG, Larkin EK, et al. Whole genome-wide scan for OSA in African-American families. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004;169:1314–21. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-493OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR. Shared genetic risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea and obesity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005;99:1600–06. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00501.2005. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled N, Kassirer M, Shitrit D, et al. The association of OSA with insulin resistance, inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Respir. Med. 2007;101:1696–701. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redline S, Storfer-Isser A, Rosen C, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing in adolescents. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007;176:401–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-375OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saar K, Geller F, Rüschendorf F, et al. Genome scan for childhood and adolescent obesity in German families. Pediatrics. 2003;111:321–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- S.A.G.E. Statistical Analysis for Genetic Epidemiology 5.4.1 Computer program package available from the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Rammelkamp Center for Education and Research, MetroHealth Campus, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell D. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. third edition Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sasanabe R, Banno K, Otake K, et al. Metabolic syndrome in Japanese patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Hypertens. Res. 2006;29:315–322. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan SR, Myers L, Berenson GS. Changes in metabolic syndrome variables since childhood in prehypertensive and hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2006;48:33–39. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000226410.11198.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam CS, Wong M, McBain R, Bailey S, Waters KA. Inflammatory measures in children with obstructive sleep apnea. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2006;42:277–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tilburg JH, Sandkuijl LA, Strongman E, et al. A genome-wide scan in type 2 diabetes mellitus provides independent replication of a susceptibility locus on 18p11 and suggests the existence of novel loci on 2q12 and 19q13. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:2223–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowsdale J, Barten R, Haude A, Stewart CA, Beck S, Wilson MJ. The genomic context of natural killer receptor extended gene families. Immunol. Rev. 2001;181:20–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1810102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhrberg M, Valiante NM, Young NT, Lanier LL, Phillips JH, Parham P. The repertoire of killer cell Ig-like receptor and CD94:NKG2A receptors in T-cells: clones sharing identical alpha beta TCR rearrangement express highly diverse killer cell Ig-like receptor patterns. J. Immunol. 2001;166:3923–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaneuva AT, Buchanan PR, Yee BJ, Grunstein RR. Ethnicity and obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:419–436. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters KA, Mast BT, Vella S, de la Eva R, O'Brien LM, Bailey S, Tam CS, Wong M, Baur LA. Structural equation modelling of sleep apnea, inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in children. J Sleep Res. 2007;16:388–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications. Part 1. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus: Report of a WHO Consultation Geneva. World Health Org., Department of Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance; 1999. WHO/NCD/NCS/99.2. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Expert Consultation Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.