Abstract

Background

Older adults (≥ 65 yr) are the fastest growing population and are presenting in increasing numbers for acute surgical care. Emergency surgery is frequently life threatening for older patients. Our objective was to identify predictors of mortality and poor outcome among elderly patients undergoing emergency general surgery.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients aged 65–80 years undergoing emergency general surgery between 2009 and 2010 at a tertiary care centre. Demographics, comorbidities, in-hospital complications, mortality and disposition characteristics of patients were collected. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify covariate-adjusted predictors of in-hospital mortality and discharge of patients home.

Results

Our analysis included 257 patients with a mean age of 72 years; 52% were men. In-hospital mortality was 12%. Mortality was associated with patients who had higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class (odds ratio [OR] 3.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.43–10.33, p = 0.008) and in-hospital complications (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.32–2.83, p = 0.001). Nearly two-thirds of patients discharged home were younger (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–0.99, p = 0.036), had lower ASA class (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.27–0.74, p = 0.002) and fewer in-hospital complications (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53–0.90, p = 0.007).

Conclusion

American Society of Anesthesiologists class and in-hospital complications are perioperative predictors of mortality and disposition in the older surgical population. Understanding the predictors of poor outcome and the importance of preventing in-hospital complications in older patients will have important clinical utility in terms of preoperative counselling, improving health care and discharging patients home.

Abstract

Contexte

La population qui connaît la croissance la plus rapide est celle des adultes âgés (≥ 65 ans). Ces personnes nécessitent un nombre croissant d’interventions chirurgicales urgentes. Or, la chirurgie d’urgence comporte souvent un risque de décès pour les patients âgés. Notre objectif était d’identifier les prédicteurs de la mortalité et d’une issue négative chez les patients âgés soumis à une chirurgie générale d’urgence.

Méthodes

Nous avons procédé à une étude de cohorte rétrospective chez des patients de 65 à 80 ans soumis à une chirurgie générale d’urgence entre 2009 et 2010 dans un centre de soins tertiaires. Nous avons recueilli les données démographiques, les comorbidités, les complications perhospitalières, la mortalité et les détails sur l’état général de santé des patients. Nous avons utilisé l’analyse de régression logistique afin de dégager les prédicteurs ajustés en fonction des covariables pour la mortalité perhospitalière et les congés hospitaliers des patients vers leur domicile.

Résultats

Notre analyse a regroupé 257 patients âgés en moyenne de 72 ans; 52 % étaient des hommes. La mortalité perhospitalière a été de 12 %. La mortalité a été associée à des patients qui se classaient dans une catégorie ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) plus élevée (rapport des cotes [RC] 3,85, intervalle de confiance [IC] de 95 % 1,43–10,33, p = 0,008) et présentaient plus de complications perhospitalières (RC 1,93, IC de 95 % 1,32–2,83, p = 0,001). Près des deux tiers des patients qui ont reçu leur congé pour retourner à la maison étaient plus jeunes (RC 0,92, IC de 95 % 0,85–0,99, p = 0,036), se classaient dans une catégorie ASA moins élevée (RC 0,45, IC de 95 % 0,27–0,74, p = 0,002) et avaient connu moins de complications perhospitalières (RC 0,69, IC de 95 % 0,53–0,90, p = 0,007).

Conclusion

La catégorie ASA et les complications perhospitalières sont des prédicteurs périopératoires de mortalité et d’état général de santé dans la population âgée soumise à la chirurgie. Comprendre les prédicteurs d’une issue négative et l’importance de prévenir les complications perhospitalières chez les patients âgés aura une importante utilité clinique pour les consultations préopératoires, l’amélioration des soins de santé et le retour des patients à la maison.

With the expected increase of the elderly population to more than 20% in 2030, a better understanding of their special needs and outcomes while undergoing emergency surgery is required.1 Correspondingly, in 2010 approximately 33% of hospital stays and 41% of hospital costs were attributed to patients older than 65 years.2 With these statistics in mind, the demand for acute surgical care of elderly patients has also been increasing.

There have been a very limited number of studies investigating the perioperative risk factors associated with emergent general surgery in patients between 65 and 80 years old.3,4 Seniors are a unique subset of patients with their own problems and vulnerabilities including the cumulative loss of physiologic reserve in almost every organ system,5 otherwise known as frailty. Recent studies involving patients older than 80 years demonstrated that age and number of comorbidities did not accurately predict poor surgical outcomes,6 and further studies have suggested that frailty measures are better overall predictors.7,8

The purpose of the present study was to characterize the subset of patients aged 65–80 years who underwent emergency general surgery and to examine their surgical outcomes, including in-hospital mortality and morbidity. We also examined factors associated with the ability to discharge patients back home without the need for in-patient rehabilitation or transfer to long-term care.

Methods

Study design and setting

The University of Alberta Human Research Ethics Board approved this research. We conducted a retrospective cohort study involving patients aged 65–80 years undergoing emergency general surgery at the University of Alberta Hospital, a tertiary care academic hospital in Edmonton, Alta., between 2009 and 2010. Data were collected from an extensive retrospective chart review. This study followed the STROBE guideline for reported retrospective cohort studies.9

Patients, variables and outcome measures

We included patients who had at least 1 emergency general surgical procedure during admission. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, sex, weight, height, prehospitalization medication use and comorbidities, were collected. Additionally, operative data, including anesthesiologist-assigned American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, operative procedure performed and surgical diagnoses, were collected. Clinical outcomes measured included in-hospital complications, length of hospital stay (LOS), in-hospital mortality and discharge disposition.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected using a Microsoft Access database, and we performed the statistical analysis using SPSS version 17.0. Frequencies and percentages were tabulated for categorical and ordinal variables; means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables. We used logistic regression analysis to identify covariate-adjusted factors associated with in-hospital mortality, complications and discharge of patients home. Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), number of prehospitalization medications, comorbidities, ASA class and number of in-hospital complications were chosen as covariates. We considered a p value < 0.05 to be evidence of an association not attributable to chance, therefore indicating statistical significance.

Results

Patient demographics, diagnoses and operative procedures

From 2009 to 2010 there were 257 patients between the ages of 65 and 80 years who underwent emergency general surgery at the University of Alberta Hospital. Mean age was 71.5 years, 52% were men, and the average BMI was 27.7 (Table 1). Comorbid illness was present in almost 95% of the included patients, with hypertension, coronary artery disease and diabetes being the most common (Table 2). In total, 93% of patients were on at least 1 medication before admission. Bowel obstruction (12.1%), cholecystitis (10.5%) and intestinal ischemia (8.6%) were the most common diagnoses (Table 3).

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics (n = 257)*

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | |

| 65–69 | 102 (39.7) |

| 70–75 | 96 (37.3) |

| 76–80 | 59 (22.9) |

| Male sex | 134 (52.1) |

| BMI (n = 246) | |

| Underweight | 9 (3.5) |

| Healthy | 74 (28.8) |

| Overweight | 91 (35.4) |

| Class I obesity | 44 (17.1) |

| Class II obesity | 16 (6.2) |

| Class III obesity | 12 (4.7) |

BMI = body mass index.

Unless otherwise indicated.

Table 2.

Patient clinical characteristics — comorbidities and medication use

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| No. of comorbidities | |

| None | 14 (5.4) |

| 1–2 | 75 (29.2) |

| 3–5 | 127 (49.4) |

| > 5 | 41 (15.9) |

| Type of comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 153 (59.5) |

| Coronary artery disease | 75 (29.2) |

| Diabetes | 58 (22.6) |

| Thyroid disease | 53 (20.6) |

| Respiratory disease (including COPD) | 53 (20.6) |

| GERD | 49 (19.1) |

| Smoking history | 36 (14.0) |

| No. of home medications | |

| None | 18 (7.0) |

| 1–2 | 43 (16.7) |

| 3–5 | 103 (40.1) |

| > 5 | 93 (36.1) |

| Home medication use | |

| Statin | 100 (38.9) |

| Diuretic | 95 (37.0) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 90 (35.0) |

| Anti-platelet | 82 (31.9) |

| ACE inhibitors | 82 (31.9) |

| β-blockers | 79 (30.7) |

| ASA class | |

| 1 | 4 (1.5) |

| 2 | 50 (19.3) |

| 3 | 96 (37.1) |

| 4 | 86 (33.2) |

| 5 | 10 (3.9) |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Table 3.

Patient clinical characteristics — most common diagnoses and procedures performed

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Bowel obstruction | 31 (12.1) |

| Cholecystitis | 27 (10.5) |

| Soft tissue infection | 22 (8.6) |

| Colorectal cancer | 22 (8.6) |

| Intestinal ischemia | 22 (8.6) |

| Other | 27 (10.5) |

| Operative procedure | |

| Cholecystectomy | 31 (12.1) |

| Colon resection with primary anastomosis | 26 (10.1) |

| Colon resection with ostomy | 23 (8.9) |

| Gastric resection/gastrostomy | 18 (7.0) |

| Herniorraphy | 17 (6.6) |

| Exporatory laparotomy | 15 (5.8) |

| Other | 35 (13.6) |

Complications

More than half of our patients (53%) experienced 1 or more complications during hospital admission. Surgical site infections (20.6%), cardiac events (20.2%), sepsis (12.1%) and postoperative bleeding (9.7%) were the most frequent complications (Table 4). Cardiac events included cardiac arrest (6.6%), myocardial infarction (5.8%) and arrhythmias (7.8%). Postoperative bleeding included the need for transfusion or operative intervention. Repeat visits to the operating room were required for 9 of the 25 patients with postoperative bleeding (3.5%). Other frequent complications identified were delirium (7.0%); pneumonia, including hospital-acquired pneumonia and aspiration (7.0%); and acute kidney injury, including any creatinine change resulting in concern by the attending physician or the need for renal replacement therapy (6.2%). Other complications, such as urinary tract infections, wound dehiscence, thromboembolic events and strokes, were less frequent.

Table 4.

Patient outcomes — complications following surgery

| Outcome | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| No. of complications | |

| None | 121 (47.1) |

| 1–2 | 78 (30.4) |

| 3–5 | 52 (20.2) |

| > 5 | 6 (2.3) |

| Type of complication | |

| Surgical site infections | 53 (20.6) |

| Superficial incisional | 16 (6.2) |

| Deep incisional | 9 (3.5) |

| Organ/space | 18 (7.0) |

| Anastomic leak | 10 (3.9) |

| Cardiac | 52 (20.2) |

| Cardiac arrest | 17 (6.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | 15 (5.8) |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 20 (7.8) |

| Sepsis | 31 (12.1) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 25 (9.7) |

| Observation | 2 (0.8) |

| Transfusion | 14 (5.4) |

| Repeat operation | 9 (3.5) |

| Delirium | 18 (7.0) |

| Pneumonia (including aspiration) | 18 (7.0) |

| Acute kidney injury | 16 (6.2) |

| UTI | 15 (5.8) |

| Wound dehiscence | 13 (5.0) |

| DVT/PE | 6 (2.3) |

| Stroke | 3 (1.2) |

DVT = deep vein thrombosis; PE = pulmonary embolus; UTI = urinary tract infection.

In-hospital mortality

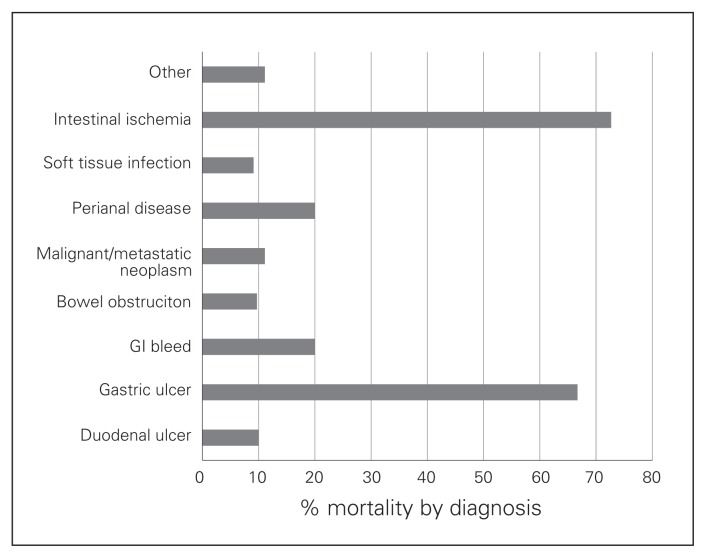

The overall in-hospital mortality was 12%. Patients with intestinal ischemia or gastric ulceration had the highest mortality (Fig. 1). We used logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with in-hospital mortality (Table 5). The ASA class (odds ratio [OR] 3.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.43–10.33, p = 0.008) and the number of complications (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.32–2.83, p = 0.001) were significantly associated with mortality. The operative diagnoses of intestinal ischemia and peptic ulcer disease were highly associated with mortality, but were not statistically significant on regression analysis (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.99–1.31, p = 0.06). Importantly, chronologic age alone or the number of comorbidities did not correspond with mortality.

Fig. 1.

Mortality based on operative diagnosis. GI = gastrointestinal.

Table 5.

Mortality outcomes — logistic regression analysis

| Covariates | β | SE | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | −0.021 | 0.623 | 0.979 (0.289–3.321) | 0.97 |

| Total no. of operations | 0.067 | 0.204 | 1.070 (0.718–1.595) | 0.74 |

| ASA | 1.347 | 0.504 | 3.845 (1.431–10.330) | 0.008 |

| Age | 0.048 | 0.065 | 1.049 (0.925–1.191) | 0.46 |

| BMI | −0.003 | 0.041 | 0.997 (0.921–1.079) | 0.94 |

| No. of medications | 0.130 | 0.143 | 1.138 (0.861–1.505) | 0.36 |

| No. of comorbidities | 0.057 | 0.178 | 1.059 (0.747–1.500) | 0.75 |

| No. of complications | 0.659 | 0.195 | 1.932 (1.318–2.833) | 0.001 |

| Operative diagnosis | 0.131 | 0.070 | 1.140 (0.994–1.308) | 0.06 |

| Operative procedure | −0.118 | 0.072 | 0.888 (0.772–1.023) | 0.10 |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; SE = standard error.

Length of stay and disposition

The median LOS was 13 days, with almost one-quarter of patients spending more than 30 days in hospital (Table 6). Nearly two-thirds of patients required additional support upon discharge, including home care services (24.4%), transfer to subacute hospitals or rehabilitation centres (23.3%) and advancement of care to assisted living or nursing home placement (2.7%; Table 6). To determine which patients were at risk of not returning home after admission, we performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 7). After controlling for confounding factors, ASA (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.27–0.74, p = 0.002), advanced age (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–0.99, p = 0.036) and the development of in-hospital complications (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53–0.90, p = 0.007) were associated with the inability to return home.

Table 6.

Patient outcomes — length of stay and disposition following surgery

| Outcome | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Length of stay, d | |

| 0–7 | 83 (32.2) |

| 8–29 | 116 (45.1) |

| > 30 | 58 (22.5) |

| Disposition | |

| Home | 159 (60.8) |

| Without additional services | 94 (36.4) |

| With homecare services | 65 (24.4) |

| Rehabilitation/home hospital | 60 (23.3) |

| Deceased | 31 (12.0) |

| Assisted living/long-term care | 7 (2.7) |

Table 7.

Discharge disposition — logistic regression analysis

| Characteristic | β | SE | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | −0.258 | 0.490 | 0.773 (0.296–2.019) | 0.60 |

| Height | 0.110 | 0.072 | 1.116 (0.969–1.286) | 0.13 |

| Weight | −0.089 | 0.068 | 0.915 (0.800–1.046) | 0.19 |

| Length of Stay | −0.009 | 0.007 | 0.991 (0.979–1.004) | 0.18 |

| Total no. of operations | −0.198 | 0.238 | 0.821 (0.515–1.308) | 0.41 |

| ASA | −0.803 | 0.259 | 0.448 (0.269–0.744) | 0.002 |

| Age | −0.085 | 0.041 | 0.918 (0.848–0.994) | 0.036 |

| BMI | 0.214 | 0.181 | 1.238 (0.869–1.765) | 0.24 |

| No. of medications | −0.121 | 0.090 | 0.886 (0.743–1.058) | 0.18 |

| No. of comorbidities | −0.102 | 0.115 | 0.903 (0.721–1.131) | 0.37 |

| No. of complications | −0.366 | 0.135 | 0.694 (0.532–0.904) | 0.007 |

| Operative diagnosis | −0.047 | 0.036 | 0.950 (0.889–1.024) | 0.19 |

| Operative procedure | 0.037 | 0.040 | 1.036 (0.960–1.122) | 0.36 |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; SE = standard error.

Discussion

Acute care surgery is being performed more frequently in frail elderly patients and can result in clinical, cognitive and functional deterioration. Our study shows that 95% of older patients present to hospital with 1 or more pre-existing comorbid illnesses. Mortality was 12%, and more than 50% of patients experienced an in-hospital complication — a very important finding since the number of in-hospital complications was significantly associated with mortality. Interestingly, chronologic age or the number of comorbidities did not correspond with mortality. More than two-thirds of the patients required additional resources on discharge from hospital. Some of the predictors associated with the inability to return home were advanced age, ASA class and the development of in-hospital complications. This knowledge can enhance perioperative counselling of patients and families about expected outcomes and assist with appropriate resource planning for patients.

Similar to other studies, we found that complications resulting from emergent surgeries can lead to worsened clinical status, additional hospital costs and, perhaps more importantly, decline in functional status requiring additional support or alternate level of care when leaving hospital.10 A recent study by Sheetz and colleagues11 reported a poor correlation between complications and mortality, but failure to rescue patients from in-hospital complications was significantly associated with mortality, and this association was greater in patients older than 75 years. In our study the most common complications were cardiac events, surgical infection/sepsis and postoperative bleeding. Cardiac events occurred in 1 of every 5 patients, which is a susbtantial number and suggests further studies are required to examine the use of postoperative telemetry in high-risk elderly patients. Delirium was documented in only 7% of patients in this study. However, we feel this event is significantly under-reported owing to lack of recognition of delirium, particularly identification of hypoactive delirium states, and poor understanding of the importance of the diagnosis. Delirium has been found in other studies to be a common postoperative complication in older patients and is associated with important adverse outcomes, such as increased LOS, higher postoperative complication rates, falls, discharge to long-term care and death.12,13 These and other complications are potentially preventable, and attention to these is paramount. Our study supports that a focus on preventing complications postoperatively can significantly impact outcomes in elderly patients.

A large proportion of the older patients in our study stayed more than 30 days in hospital and required additional support on discharge. Unfortunately, acute care models rarely take into account the special needs of this population; for example, proactive planning of services, such as rehabilitation, is seldom done.14 Acute hospitals continue to be geared to provide care for those with single acute illnesses rather than those with multiple acute and chronic conditions. This can result in poor postsurgical outcomes, an increased requirement for care, reduced quality of life, increased dependency and increased health care resource utilization. Our centre will be exploring how to improve outcomes by examining new care models, such as acute care for the elderly (ACE) units applied to a surgical setting where there is a focus on screening for early identification of geriatric syndromes, family and caregiver involvement at all stages of care, interdisciplinary assessments and an environment supportive of discharge planning and community services.15–17

Our study reinforces that higher ASA class is associated with mortality following emergency general surgery in elderly patients. It should be mentioned that despite being a statistically significant variable, the ASA class had a wide CI, likely associated with our relatively small data set, and therefore we cannot accurately describe the direct magnitude of its effect on mortality. Three of the more common scoring systems to predict outcome are the Reported Edmonton Frail Scale (REFS), the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) and the Physiologic and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Morbidity and mortality (POSSUM). There are several reasons these are often not used in the acute surgical setting; the APACHE II score requires an extensive workup often not conducive to acute surgical situations,18 the POSSUM scoring system may overestimate mortality in low-risk patients while underestimating the risk in elderly patients or those undergoing emergency surgery,19–21 and the REFS scale uses more comprehensive subjective geriatric measures (v. physiologic),22 which are not always possible to obtain quickly preoperatively. By contrast, ASA class can be quickly determined on admission.23 While anesthesiologists often use this score, our study demonstrates the value of surgeons using ASA class for preoperative risk stratification and discussions.

Limitations

Our study is limited by its retrospective single-centre design and small sample size. Our statistical analysis did not take into account the severity of certain comorbidities, therefore it might be worthwhile to incorporate the Charlson Comorbidity Index24 instead of the total number of comorbidities in future studies. In addition, this study focused on the elderly patients who underwent an operation but did not examine outcomes of the patients who had nonoperative management. For example, some patients may have been treated nonoperatively (i.e., medical management for acute cholecystitis) or as per end-of-life care goals or personal wishes to avoid surgery. This is an important cohort of patients who would benefit from studies in the future.

Conclusion

Older patients undergoing emergency surgery are at very high risk for in-hospital complications. The ASA class and the development of an in-hospital complication are independent predictors of mortality; these factors were associated with the inability to return home. Understanding the perioperative factors associated with adverse outcomes can allow for identification of at-risk patients to allow for development of tailored preventative strategies and resource planning to improve the outcome in elderly emergency surgical patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the University of Alberta’s ACES group for their support. The ACES group includes Drs. R. Brisebois, K. Buttenschoen, K. Fathimani, S.M. Hamilton, R.G. Khadaroo, G.M. Lees, T.P.W. McMullen, W. Patton, M. van Wijngaarden-Stephens, J.D. Sutherland, H. Wang, S.L. Widder and D.C. Williams.

Footnotes

This research was presented at the Academic Surgical Congress on February 4–6, 2014 in San Diego, California. This conference is composed of the Association for Academic Surgery (AAS) and Society of University Surgeons (SUS).

Funding: Funding for this study was from the M.S.I. Foundation (R. Khadaroo).

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: R. Khadaroo designed the study. M. Lees, S. Merani and K. Tauh acquired the data, which all authors analyzed. All authors wrote and reviewed the article and approved the final version for publication.

References

- 1.Vincent G, Velkoff V. The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050 population estimates and projections. U.S. Census Bureau; May, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Steiner C. HCUP Statistical Brief #146. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jan, 2013. Costs for hospital stays in the United States, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speicher PJ, Lagoo-Deenadayalan SA, Galanos AN, et al. Expectations and outcomes in geriatric patients with do-not-resuscitate orders undergoing emergency surgical management of bowel obstruction. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:23–8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rix TE, Bates T. Pre-operative risk scores for the prediction of outcome in elderly people who require emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2007;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dardik A, Berger D, Rosenthal R. Surgery in the geriatric patient. In: Townsend C, Beauchamp R, Evers B, et al., editors. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. 19th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012. pp. 328–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merani S, Payne J, Padwal RS, et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality and complications in very elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2014;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Partridge JS, Harari D, Dhesi JK. Frailty in the older surgical patient: a review. Age Ageing. 2012;41:142–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du Y, Karvellas CJ, Baracos V, et al. Sarcopenia is a predictor of outcomes in very elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery. Surgery. 2014;156:521–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akinbami F, Askari R, Steinberg J, et al. Factors affecting morbidity in emergency general surgery. Am J Surg. 2011;201:456–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheetz KH, Waits SA, Krell RW, et al. Improving mortality following emergent surgery in older patients requires focus on complication rescue. Ann Surg. 2013;258:614–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a5021d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271:134–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Abelseth GA, Khandwala F, et al. A pragmatic study exploring the prevention of delirium among hospitalized older hip fracture patients: applying evidence to routine clinical practice using clinical decision support. Implement Sci. 2010;5:81. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Morton NA, Keating JL, Jeffs K. Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD005955. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005955.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1338–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steele JS. Current evidence regarding models of acute care for hospitalized geriatric patients. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31:331–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed NN, Pearce SE. Acute care for the elderly: a literature review. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13:219–25. doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiteley MS, Prytherch DR, Higgins B, et al. An evaluation of the POSSUM surgical scoring system. Br J Surg. 1996;83:812–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vather R, Zargar-Shoshtari K, Adegbola S, et al. Comparison of the possum, P-POSSUM and CR-POSSUM scoring systems as predictors of postoperative mortality in patients undergoing major colorectal surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:812–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Racz J, Dubois L, Katchky A, et al. Elective and emergency abdominal surgery in patients 90 years of age or older. Can J Surg. 2012;55:322–8. doi: 10.1503/cjs.007611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilmer SN, Perera V, Mitchell S. The assessment of frailty in older people in acute care. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28:182–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keats AS. The ASA classification of physical status — a recapitulation. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:233–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197810000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]