Abstract

Background

The impact of the age of stored red blood cells on mortality in patients sustaining traumatic injuries requiring transfusion of blood products is unknown. The objective of this systematic review was to identify and describe the available literature on the use of older versus newer blood in trauma patient populations.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Lilac and the Cochrane Database for published studies comparing the transfusion of newer versus older red blood cells in adult patients sustaining traumatic injuries. Studies included for review reported on trauma patients receiving transfusions of packed red blood cells, identified the age of stored blood that was transfused and reported patient mortality as an end point. We extracted data using a standardized form and assessed study quality using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

Results

Seven studies were identified (6780 patients) from 3936 initial search results. Four studies reported that transfusion of older blood was independently associated with increased mortality in trauma patients, while 3 studies did not observe any increase in patient mortality with the use of older versus newer blood. Three studies associated the transfusion of older blood with adverse patient outcomes, including longer stay in the intensive care unit, complicated sepsis, pneumonia and renal dysfunction. Studies varied considerably in design, volumes of blood transfused and definitions applied for old and new blood.

Conclusion

The impact of the age of stored packed red blood cells on mortality in trauma patients is inconclusive. Future investigations are warranted.

Abstract

Contexte

On ne connaît pas l’incidence de la durée de stockage des globules rouges sur la mortalité des patients atteints de lésions traumatiques qui ont besoin de transfusions de produits sanguins. L’objectif de cette revue systématique était de trouver et d’analyser la documentation scientifique qui compare les transfusions de sang chez les patients adultes victimes de trauma en fonction de la durée de stockage du sang.

Méthodes

Nous avons effectué des recherches sur PubMed, Embase et Lilac et dans la Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Les études retenues portaient sur des transfusions de concentré de globules rouges chez les patients atteints de lésions traumatiques, tenaient compte de la durée de stockage du sang transfusé et faisaient état des décès de patients. Nous avons extrait les données à l’aide d’un formulaire normalisé et évalué la qualité des études selon l’échelle Newcastle–Ottawa.

Résultats

Nous avons sélectionné 7 études (totalisant 6780 patients) parmi les 3936 résultats de la recherche initiale. D’un côté, 4 études rapportaient que la transfusion de sang dont la durée de stockage était longue était indépendamment associée à l’augmentation de la mortalité chez les patients atteints de lésions traumatiques; de l’autre, 3 études ne faisaient état d’aucune augmentation de la mortalité en fonction de la durée de stockage du sang transfusé. Trois études associaient la transfusion de sang stocké depuis longtemps à des résultats indésirables, notamment un séjour prolongé aux soins intensifs ainsi que la septicémie compliquée, la pneumonie et l’insuffisance rénale. Le modèle d’étude, le volume des transfusions et les définitions de ce qui constitue une longue ou une courte durée de stockage du sang variaient considérablement d’une étude à l’autre.

Conclusion

Les résultats de cette revue systématique des effets de la durée de stockage des concentrés de globules rouges sur la mortalité des patients atteints de lésions traumatiques ne sont pas concluants. D’autres recherches devront être menées pour éclaircir la question.

The transfusion of packed red blood cells (pRBCs) is considered a cornerstone principle for the management of traumatically injured patients.1,2 In cases of both blunt and penetrating trauma, the loss of intravascular blood volume is a common occurrence — so much so that any degree of hemodynamic instability is assumed to reflect hemorrhage.3 Although crystalloid intravenous fluids are often used in these patients to establish hemodynamic stability, the early administration of pRBCs has also been advocated.4,5 However, the use of donor blood products is not without risk of complication. Recent investigations in cardiac surgery,6,7 interventional cardiology8 and critical care9–12 have determined that the transfusion of older pRBCs is associated with increased adverse events, including increased mortality. Although the exact mechanism responsible for this is unknown, it is thought that structural, biochemical and immunologic changes occur within RBCs during their storage (also known as “storage lesion”) and that these changes limit the benefits of pRBC transfusions.13–15

Previous studies investigating the age of transfused blood in patients with traumatic injury have yielded inconsistent results.16–18 To our knowledge, no systematic review currently exists that exclusively examines the impact of the age of transfused RBCs on mortality in the trauma patient population, although other patient populations have been investigated.19–24 The objective of this review was to assess the available evidence for the impact of the age of stored RBCs given as transfusions in the trauma population on patient mortality.

Methods

Literature search

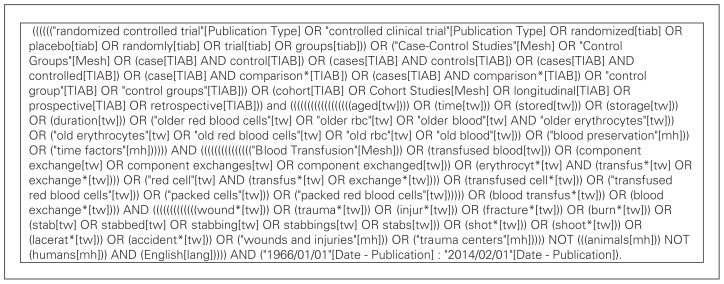

A systematic search of PubMed (1966 to February 2014), Embase (1974 to February 2014), Cochrane and Lilac databases was executed in February 2013 and updated in February 2014. We examined all articles describing the transfusion of stored pRBCs in a trauma patient population and reporting on the age of the blood transfused or the duration for which it was stored. Our a priori outcome was all-cause mortality, although this was not specified in the original search parameters in order to conduct a broad and exhaustive search that identified all relevant investigations. A university librarian assisted with the development of the search strategy. Our specific research question was the following: In patients sustaining traumatic injuries presenting to an emergency department or trauma centre and requiring transfusion of pRBCs during their initial management, does the age of the transfused blood products subsequently have an impact on patient mortality? Search terms (medical subject headings, Emtree headings and free text words) related to trauma patients, age of stored blood, transfusion of pRBCs and patient mortality were used with Boolean logic to identify all potentially relevant articles. No language restrictions were applied.

Study eligibility criteria were determined a priori and used to review citations for relevant studies. Criteria for inclusion were the following: the study was specific to blunt and/or penetrating trauma population, the study population received a transfusion of RBCs, the age of the transfused blood products was described and the study included the end point of patient mortality. All citations were reviewed in accordance with these criteria. As pRBCs are the most frequently transfused blood product in the trauma population, we limited our search to studies that examined the storage age of RBCs; studies that focused on the transfusion of other blood products, such as platelets or plasma, were excluded.

A single author (N.S.) initially reviewed the titles of all studies identified using the search strategy. Studies that were not relevant and any duplicate articles were excluded. Two of us (N.S. and P.F.) independently reviewed the abstract and/or full text of publications related to both the trauma population and the receipt of blood products. Studies that met all of the eligibility criteria were then reviewed by a third author (R.G.) for inclusion. Any discrepancies regarding the selection of articles for inclusion were resolved by consensus among the study authors.

Study selection

Our study population was trauma patients of any age who received a transfusion of RBCs at an emergency department or trauma centre. We included any randomized controlled trial, case–control series or cohort study that met the eligibility criteria. In addition, previously published review papers or meta-analyses related to RBC storage lesions including but not specific to the trauma population were reviewed to identify additional studies.

Our primary outcome of interest was patient mortality. Secondary outcomes included intensive care unit (ICU) admission and length of stay, renal failure, severe sepsis and multiorgan failure, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and any other complications that were reported. Since a standard definition for the age of stored blood does not currently exist, we also extracted the definition that was used for the age of stored blood from each included study.

Critical appraisal of included studies

The quality of all included studies was assessed independently by a single blinded author (M.E.) using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies.25 Studies were evaluated based on their selection of study groups, their comparability and their assessment of the outcome of interest. A score was calculated for each study, with a maximum score of 9 representing the highest methodological quality.

Data extraction

Data elements were evaluated for all publications independently by a single nonblinded author (N.S.) using a standardized data collection form. Extracted information included the year and country of publication, patient age and sex, inclusion and exclusion criteria, primary and secondary outcomes, definitions of old versus new blood, injury severity scores (ISS), blunt and penetrating trauma population distribution and strength of association (odds ratios [OR], relative risks [RR]) between the age of transfused blood and outcomes of interest. Our intent was to perform a meta-analysis of previous studies. Only data explicitly stated in the manuscript of included studies were extracted. Study authors were contacted when clarification of data was required.

Results

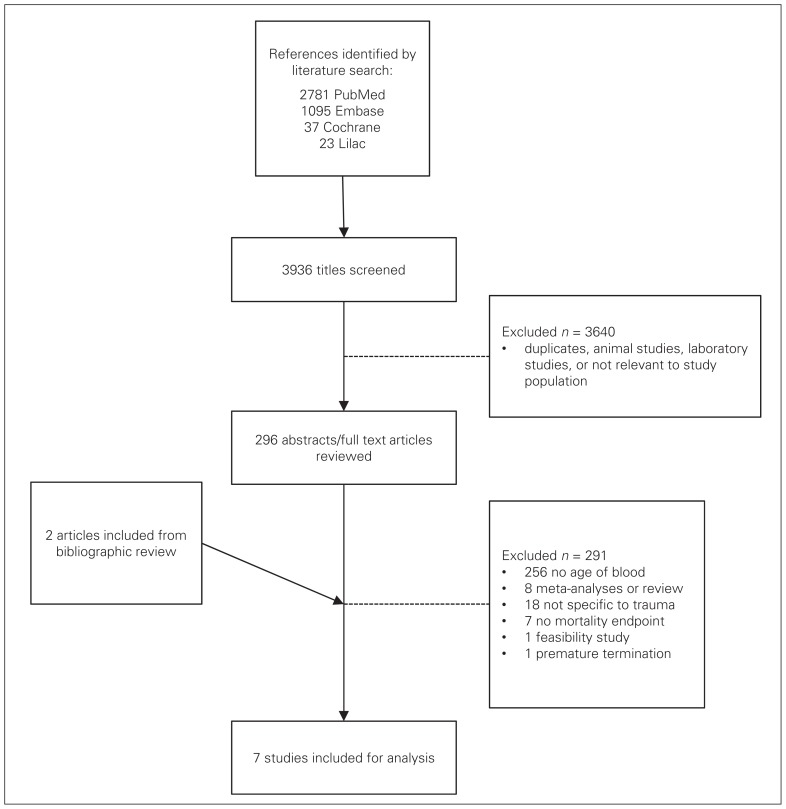

Seven studies met all of our selection criteria (Fig. 1). We excluded 289 studies because they did not report the age of transfused blood or storage lesion (n = 256), they were review articles or meta-analyses (n = 7), they were not specific to the trauma population (n = 18), they lacked reporting of mortality as an end point (n = 7), or the study was prematurely terminated owing to logistical issues at the investigation site (n = 1). Three of these studies that are relevant in the trauma literature on this subject were excluded because the primary outcome measured was not mortality.17,26,27 We identified 2 additional studies through bibliographic review of included studies;28,29 neither was included for analysis (bringing the total number of excluded studies to 291) because 1 was a review article and 1 a feasibility study. Our search strategy is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 1.

Study selection.

Fig. 2.

Search strategy for PubMed.

Study characteristics and design

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and design of the 7 included studies,30–36 representing a total of 6780 patients. All included studies were single-centre retrospective cohort studies performed at trauma centres in the United States and published between the years 2005 and 2010. Studies were limited to adult patients, a majority of whom had incurred blunt trauma (range 74.4%–100%). All studies reported all-cause in-hospital mortality as a primary outcome. The mean ISS varied between 14.4 and 26.3,30,32–34 and the median ISS varied between 18 and 29.31,35,36 Overall mortality ranged from 2.7% to 20.3%.

Table 1.

Study and patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hassan et al.31 | Murrell et al.36 | Phelan et al.35 | Spinella et al.32 | Weinberg et al.33 | Weinberg et al.30 | Weinberg et al.34 | |

| No. of patients | 820 | 275 | 399 | 202 | 1813 | 1624 | 1647 |

| Study type | R, C, SC | R, C, SC | R, C, SC | R, C, SC | R, C, SC | R, C, SC | R, C, SC |

| Age, yr, mean or median [IQR] | 40 | 37 [22–53] | 41.6 | 46.5 | 41 | 43.2 | 41.3 |

| Male sex, % | 67 | 67 | 78.2 | 74.8 | 65 | 70.6 | 66.7 |

| Blunt mechanism, % | 89 | NR | 76.4 | 92.6 | 76 | 100 | 74.4 |

| ISS, mean (range) or median [IQR] | 27 [18–34] | 18 [10–29] | 29 [22.0–39.5] | 24 (13.5–34) | 26 (NR) | 14.4 (1–24) | 26.3 (NR) |

| Overall mortality, % | 14 | 19 | 19.5 | 20.3 | 10 | 17.7 | 2.7 |

| Inclusion criteria | Transfusion in ICU within 24 hr | Transfusion of ≥ 1u pRBC | Transfusion ≥ 6u pRBC, surviving 48 hr | Transfusion ≥ 5u pRBC, ICU admission | Transfusion ≥ 1u pRBC in 24 hr | ISS < 25, no pRBC given in first 48 hr, ICU admission | Transfusion ≥ 1u pRBC in 24 hr |

| Exclusion criteria | NR | NR | NR | Patients who died in the ED | Patients who died within the first 24–48 hr | Patients who died within first 24–48 hr | Patients given new and old blood in first 24 hr |

| New blood definition, d in storage | ≤ 14 | Variable | Mean 14 | < 28 | < 14 | < 14 | < 14 |

| Old blood definition, d in storage | > 14 | Variable | Mean 21 | ≥ 28 | ≥ 14 | ≥ 14 | ≥ 14 |

| Total pRBC units transfused, mean ± SD, mean (range) or median [IQR] | 6 [4–11] | 3 [2–6] | 16.5 ± 16.3 | 9 [6–12.5] | 4.9 (NR) | 5.2 (1–104) | 3.2 ± 1.8 |

C = cohort; ED = emergency department; ICU = intensive care unit; ISS = injury severity score; IQR = interquartile range; NR = not reported; pRBC = packed red blood cells; R = retrospective; SC = single centre; SD = standard deviation; u = unit(s).

Definitions for the age of stored blood varied among the 7 studies. Blood was considered old if it was in storage 14 days or longer,30,33,34 longer than 14 days,31 or 28 days or longer.32 One study35 used the mean age of all units received within 14 days to define new blood and the mean age of all units stored 21 days or longer to define old blood, and 1 study36 developed a composite variable that was defined by the proportionate age of each blood unit averaged over all units transfused and then multiplied by the total number of units transfused. The 7 studies also differed considerably in their eligibility criteria and the volume of pRBCs transfused. Owing to the heterogeneity in study design and populations, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis. All studies were of high quality based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, scoring at least 7 out of a possible 9 points (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies

| Factor | Study* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hassan et al.31 | Murrell et al.36 | Phelan et al.35 | Spinella et al.32 | Weinberg et al.33 | Weinberg et al.30 | Weinberg et al.34 | |

| Selection | |||||||

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ |

| Selection of the nonexposed cohort | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ |

| Ascertainment of exposure | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | — | ★ |

| Demonstration the outcome of interest not present at start of study | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ |

| Comparability | |||||||

| Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | ★★ | ★★ | ★★ | ★★ | ★★ | ★★ | ★★ |

| Outcome | |||||||

| Assessment of outcome | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ |

| Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ |

| Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | — | — | — | ★ | — | — | — |

| Total score | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

Based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies, each study was awarded a maximum of 1 star for each item within the Selection and Outcome categories, and a maximum of 2 stars for the Comparability category. Total scores for each study were calculated by adding 1 point for each star awarded, with a maximum possible score of 9.

Age of transfused blood and trauma patient outcomes

The age of transfused blood and its association with trauma patient outcomes is summarized in Table 3. Evidence for an association between the age of blood and in-hospital mortality was conflicting, as 4 studies30,32–34 found transfusion of older blood to be associated with increased mortality in trauma patients, while 3 studies31,35,36 reported no increase in mortality associated with older versus newer blood. Two studies transfused RBCs that had been leukoreduced before storage; 1 study35 reported no increased risk of death associated with transfusion of prestorage leukoreduced RBCs but could not determine whether the effect on mortality was neutral or protective, and another study33 reported increased mortality associated with transfusion of older blood despite universal leukoreduction.

Table 3.

Association between the age of transfused blood and trauma patient outcomes

| Study | Age of blood transfused* (quantity) | Outcome | OR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hassan et al.31 | Old (≥ 7u) | Mortality | NS | — |

| Old (≥ 7u) | Complicated sepsis | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) | — | |

| Murrell et al.36 | Old | In-hospital mortality | NS | — |

| Old | Need for ICU care | NS | — | |

| Old | Longer ICU stay | — | 1.15 (1.11 – 1.20) | |

| Phelan et al.35 | Mean 14 d | Mortality | 0.426 (0.182 – 0.998) | — |

| Mean 21 d | Mortality | 0.439 (0.225 – 0.857) | — | |

| Spinella et al.32 | Old (≥ 5u) | In-hospital mortality | 4.0 (1.34 – 11.61) | — |

| Old (≥ 10u) | In-hospital mortality | 8.9 (2 – 40) | — | |

| Weinberg et al.33 | Old (overall) | Mortality | NS | — |

| Old (1–2u) | Mortality | NS | — | |

| Old (≥ 3u) | Mortality | 2.18 (1.00 – 4.97) | — | |

| Weinberg et al.30 | New | Mortality | NS | — |

| Old | Mortality | 1.12 (1.02 – 1.23) | — | |

| New | Renal dysfunction | NS | — | |

| Old | Renal dysfunction | 1.18 (1.07 – 1.29) | — | |

| New | Pneumonia | NS | — | |

| Old | Pneumonia | 1.10 (1.04 – 1.17) | — | |

| New | ARDS | NS | — | |

| Old | ARDS | NS | — | |

| Weinberg et al.34 | 1–2u old v. new | In-hospital mortality | — | NS |

| ≥ 3u old v. new | In-hospital mortality | — | 1.57 (1.14 – 2.15) |

ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI = confidence interval; ICU = intensive care unit; OR = odds ratio; NS = not significant; RR = relative ristk; u = unit(s).

Based on individual study definitions for old and new blood.

In addition to the outcome of mortality, some studies investigated additional patient outcomes and their association with the age of transfused blood. One study31 examined the incidence of complicated sepsis and reported that after controlling for age, sex, ISS and total pRBC units transfused, the administration of older blood was significantly associated with the development of complicated sepsis (OR 1.9, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–3.4). Another study32 looked at the incidence of DVT and found it to be higher in patients transfused with older blood than in patients receiving newer blood (17 of 39 [43.6%] v. 7 of 44 [15.9%], p = 0.006). A third study36 examined patient length of stay in the ICU and the requirement for ICU care and reported that patients receiving older blood had significantly longer ICU stays than patients receiving newer blood (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.11–1.20) but did not have significantly greater need for ICU care. One of the included studies30 focused on outcomes in less severely injured patients and reported that the transfusion of older blood was associated with renal dysfunction (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02–1.23) and pneumonia (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.04–1.17) but was not significantly associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Discussion

We have conducted, to our knowledge, the first systematic review examining the impact of the age of transfused RBCs on trauma patient mortality. Our broad search strategy identified 7 studies from the published literature involving a total of 6780 patients. Within these 7 studies, there was substantial heterogeneity in the applied definitions for old versus new blood. The storage time after which new blood was defined as old blood ranged from 14 to 28 days. Studies also varied in the volume of blood transfused, ranging from 1 to 6 units. Conclusions drawn from individual studies on the impact of the age of stored blood on patient mortality ranged from neutral to negative. Overall, the results of the 7 studies included in this review are inconclusive with regards to the effect of the age of stored RBCs on trauma patient mortality.

The early transfusion of blood products, often as part of a massive transfusion protocol, and the avoidance of large volume crystalloid resuscitations has become the standard of care in critically ill patients.37 Research into the impact of the age of stored RBCs in a variety of patient populations has evolved over the past decade. Studies from the cardiac surgery literature have generally shown mixed results; however, several large retrospective studies have demonstrated increased mortality in patients transfused with older blood.6,7 Recently, 2 large studies in cardiology patients, including 1 study of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), demonstrated increased mortality in patients receiving transfusions of older blood.38,39 Within the critical care literature, there are a number of smaller retrospective studies that have been performed, some of which included trauma patients and reported mixed results regarding the impact of older blood on patient mortality. In a multicentre observational study of 757 ICU patients, an increase in mortality was observed for patients who were transfused with older blood.40 The age of blood evaluation (ABLE) study is a double-blind, multicentre, parallel randomized controlled clinical trial of 2510 critically ill adults that is currently underway in 3 countries (Canada, France, United Kingdom) to test if transfusion with RBCs stored for 7 days or less is associated with lower 90-day mortality than transfusion with standard-issue RBCs (2–42 days of storage).41 If a difference is found, the results of the ABLE study will be applicable to critically ill adults but not to other patients.

In Canada, the supply of red blood cells is based on public donation through hospital-based or national organizations, such as Canadian Blood Services. Current practice in Canada is to transfuse older blood first to avoid waste. However, once blood donation has occurred it must be stored, and RBCs are known to undergo a series of physical and biochemical changes during storage, which are collectively known as “storage lesion.”13–15 These changes include degradation of erythrocytic 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG), which diminishes the binding affinity of RBCs for oxygen.14 Storage lesion also includes depletion of cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) stores, which reduces the ability of sodium–potassium channels, glucose transport and oxidative stress defence mechanisms to function.42,43 Additionally, the shape of the RBC degrades in a linear fashion from typical biconcave discs to spiculated echinocytes to spherocytes, increasing viscosity, reducing the ability to transverse small capillary beds, and increasing cell aggregation and potentially thrombus formation, as well as proinflammatory and prothrombotic effects of free heme from hemolysis of stored RBCs.43 These changes are thought to have adverse effects on or limit cell survival in patients who receive transfusions of older blood. Historically, donor leukocyte contamination was thought to illicit adverse responses from the recipient’s immune system; however, since pretransfusion leukoreduction is now standard practice, this risk has largely been negated.14

In the trauma patient population, we identified 4 single-centre retrospective studies examining the impact of storage lesion using a cutoff of 14 days to denote old blood. While studies have varied in their inclusion criteria, particularly the number of units transfused, there is a trend toward studies reporting an increase in adverse patient outcomes following transfusion of older blood, including multiorgan failure,26 longer ICU/hospital length of stay,27 pneumonia44 and other major infections17,45 and all-cause mortality.30,32–34 Trauma patients who receive large volumes of blood as part of massive transfusion protocols may have an increased risk of death compared with those who receive smaller total volumes of old blood, suggesting that a dose effect of older blood may exist for various outcomes.28 Three of the studies32–34 included in our review suggested that an increased overall volume of transfused blood likely reflects greater injury with an inherent increase in mortality. Within the transfusion literature, a standardized definition of old versus new blood does not exist. The most commonly used cutoff reported in published studies is 14 days, which dichotomizes all transfused pRBCs into 1 of 2 treatment arms. This cutoff is derived from several biochemical laboratory studies demonstrating that physiologic changes occur within stored blood, and that after 14 days in storage these changes may have a negative impact in transfusion recipients.43 We identified only 1 study35 that analyzed the mean age of blood as a continuous variable. Within our included studies, there was considerable variability among the definitions used for the age of blood in storage, making it difficult to compare studies since blood considered to be old in one study would be considered new in another. Examining the age of transfused blood as a continuous variable may help to identify whether or not a transition age between new and old actually exists. Consistency of a clear definition for the age of stored blood is paramount for further research within the field.

Limitations

It is important to note that 3 of the included studies30,33,34 accounted for the majority of patients (5084 of 6780) and were all performed at the same institution and using the same database. After discussion with the lead investigator of these 3 studies, it is likely that some patients were included in multiple studies. However, because the inclusion criteria were different and there was not substantial overlap of patients, we chose to include all patients from these 3 studies in our review.

As with all systematic reviews, the quality of our study is based on the quality of our initial literature search. To avoid missing any potentially appropriate studies during our search, we purposefully kept our search terms broad in order to generate wide search results, which were then reviewed. For example, we did not require any specifics regarding trauma as a search term. We were not specific in our initial search for age of blood or storage lesion, as these are not universally used terms; instead, we manually selected studies with those terms during the search. Furthermore, there was substantial heterogeneity in study design, eligibility criteria, volumes of transfused blood and definitions used for old and new blood across all 7 studies. These limitations draw into question the generalizability of these study results and reinforce the need to establish standard definitions for the age of stored blood.

Clinical relevance

Transfusion of RBCs is a key management principle in the traumatically injured patient. Previous findings suggest the transfusion of older RBCs is associated with adverse effects. If the transfusion of older blood in trauma patients is associated with poor patient outcomes, it may promote the use of newer blood in this high-risk patient population. Several studies have shown that the negative effects of transfusing older blood are more significant when larger volumes of blood are transfused, although the true effect is currently unknown. However, should a properly conducted clinical investigation demonstrate that the transfusion of older blood negatively impacts patient outcomes, transfusion strategies targeting the use of new blood in trauma patients would represent an important shift in clinical practice.

Conclusion

The literature on the impact of the age of transfused blood on the mortality of trauma patients is inconclusive at present. The few studies available differ considerably in design and in their definitions for the age of stored blood. Agreement on a consensus definition for old and new blood is a crucial step toward better understanding the association between the age of transfused blood and poor patient outcomes.

Footnotes

This research was presented in part as a poster at the Maritime Trauma and Emergency Medicine Conference in Moncton, NB, Apr. 3–5, 2014, and at the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians Annual Meeting in Ottawa, Ont., May 31–June 4, 2014.

Funding: This study was funded by a Clinician Scientist Award from the Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: N. Sowers and R. Green designed the study. N. Sowers and P. Froese acquired the data, which N. Sowers, M. Erdogan and R. Green analyzed. N. Sowers, M. Erdogan and R. Green wrote the article, which all authors reviewed and approved for publication.

References

- 1.Farion KJ, McLellan BA, Boulanger BR, et al. Changes in red cell transfusion practice among adult trauma victims. J Trauma. 1998;44:583–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraga GP, Bansal V, Coimbra R. Transfusion of blood products in trauma: an update. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:253–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dries DJ. The contemporary role of blood products and components used in trauma resuscitation. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:63. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-18-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaur P, Basu S, Kaur G, et al. Transfusion protocol in trauma. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4:103–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.76844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kautza BC, Cohen MJ, Cuschieri J, et al. Changes in massive transfusion over time: An early shift in the right direction? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:106–11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182410a3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1229–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basran S, Frumento RJ, Cohen A, et al. The association between duration of storage of transfused red blood cells and morbidity and mortality after reoperative cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:15–20. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000221167.58135.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyle BJ, Rihal CS, Gastineau DA, et al. Bleeding, blood transfusion, and increased mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: implications for contemporary practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2019–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tinmouth A, Fergusson D, Yee IC, et al. Clinical consequences of red cell storage in the critically ill. Transfusion. 2006;46:2014–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiraly LN, Underwood S, Differding JA, et al. Transfusion of aged packed red blood cells results in decreased tissue oxygenation in critically injured trauma patients. J Trauma. 2009;67:29. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181af6a8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karkouti K. From the journal archives: the red blood cell storage lesion: past, present, and future. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61:583–6. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purdy FR, Tweeddale MG, Merrick PM. Association of mortality with age of blood transfused in septic ICU patients. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:1256–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03012772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flegel WA, Natanson C, Klein HG. Does prolonged storage of red blood cells cause harm? Br J Haematol. 2014;165:3–16. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kor DJ, Van Buskirk CM, Gajic O. Red blood cell storage lesion. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2009;9(Suppl 1):21–7. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2009.2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lion N, Crettaz D, Rubin O, et al. Stored red blood cells: a changing universe waiting for its map(s) J Proteomics. 2010;73:374–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinberg JA, Barnum SR, Patel RP. Red blood cell age and potentiation of transfusion-related pathology in trauma patients. Transfusion. 2011;51:867–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Offner PJ, Moore EE, Biffl WL, et al. Increased rate of infection associated with transfusion of old blood after severe injury. Arch Surg. 2002;137:711–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vamvakas EC. Meta-analysis of clinical studies of the purported deleterious effects of “old” (versus “fresh”) red blood cells: Are we at equipoise? Transfusion. 2010;50:600–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Watering LM. Age of blood: Does older blood yield poorer outcomes? Curr Opin Hematol. 2013;20:526–32. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328365aa3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimrin AB, Hess JR. Current issues relating to the transfusion of stored red blood cells. Vox Sang. 2009;96:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lelubre C, Piagnerelli M, Vincent JL. Association between duration of storage of transfused red blood cells and morbidity and mortality in adult patients: Myth or reality? Transfusion. 2009;49:1384–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen B, Matot I. Aged erythrocytes: A fine wine or sour grapes? Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(Suppl 1):62–70. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang D, Sun J, Soloman SB, et al. Transfusion of older stored blood and risk of death: a meta-analysis. Transfusion. 2012;52:1184–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marik PE, Corwin HL. Efficacy of red blood cell transfusion in the critically ill: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2667–74. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181844677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa (ON): Ottawa Health Research Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zallen G, Offner PJ, Moore EE, et al. Age of transfused blood is an independent risk factor for postinjury multiple organ failure. Am J Surg. 1999;178:570–2. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keller ME, Jean R, LaMorte WW, et al. Effects of age of transfused blood on length of stay in trauma patients: a preliminary report. J Trauma. 2002;53:1023–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200211000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aubron C, Nichol A, Cooper DJ, et al. Age of red blood cells and transfusion in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3:2. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohn SM, DeRosa M, Kumar A, et al. Impact of the age of transfused red blood cells in the trauma population: a feasibility study. Injury. 2014;45:605–11. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinberg JA, McGwin G, Jr, Marques MB, et al. Transfusions in the less severly injured: Does age of transfused blood affect outcomes? J Trauma. 2008;65:794–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318184aa11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassan M, Pham TN, Cuschieri J, et al. The association between the transfusion of older blood and outcomes after trauma. Shock. 2011;35:3–8. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181e76274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spinella PC, Carroll CL, Staff I, et al. Duration of red blood cell storage is associated with increased incidence of deep vein thrombosis and in hospital mortality in patients with traumatic injuries. Crit Care. 2009;13:R151. doi: 10.1186/cc8050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinberg JA, McGwin G, Jr, Griffin RL, et al. Age of transfused blood: an independent predictor of mortality despite universal leukoreduction. J Trauma. 2008;65:279–82. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817c9687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinberg JA, McGwin G, Jr, Vandromme MJ, et al. Duration of red cell storage influences mortality after trauma. J Trauma. 2010;69:1427–31. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181fa0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phelan HA, Gonzalez RP, Patel HD, et al. Prestorage leukoreduction ameliorates the effects of aging on banked blood. J Trauma. 2010;69:330–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e0b253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murrell Z, Haukoos JS, Putnam B, et al. The effect of older blood on mortality, need for ICU care, and the length of ICU stay after major trauma. Am Surg. 2005;71:781–5. doi: 10.1177/000313480507100918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ball CG. Damage control resuscitation: history, theory and technique. Can J Surg. 2014;57:55–60. doi: 10.1503/cjs.020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson SD, Janssen C, Fretz EB, et al. Red blood cell storage duration and mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2010;159:876–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eikelboom JW, Cook RJ, Liu Y, et al. Duration of red cell storage before transfusion and in-hospital mortality. Am Heart J. 2010;159:737–743.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pettilä V, Westbrook AJ, Nichol AD, et al. Age of red blood cells and mortality in the critically ill. Crit Care. 2011;15:R116. doi: 10.1186/cc10142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lacroix J, Hébert P, Fergusson D, et al. The age of blood evaluation (ABLE) randomized controlled trial: study design. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hess JR, Greenwalt TG. Storage of red blood cells: new approaches. Transfus Med Rev. 2002;16:283–95. doi: 10.1053/tmrv.2002.35212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavenski K, Saidenberg E, Lavoie M, et al. Red blood cell storage lesions and related transfusion issues: a Canadian Blood Services research and development symposium. Transfus Med Rev. 2012;26:68–84. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vandromme MJ, McGwin G, Jr, Weinberg JA. Blood transfusion in the critically ill: Does storage age matter? Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:35. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Juffermans NP, Vlaar AP, Prins DJ, et al. The age of red blood cells is associated with bacterial infections in critically ill trauma patients. Blood Transfus. 2012;10:290–5. doi: 10.2450/2012.0068-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]