Abstract

Background

The antifibrinolytic drug tranexamic acid is currently being rediscovered for both trauma and major surgery. Intravenous administration reduces the need for blood transfusion and blood loss by about one-third, but routine administration in surgery is not yet advocated owing to concerns regarding thromboembolic events. The aim of this study was to investigate whether topical application of tranexamic acid to a wound surface reduces postoperative bleeding.

Methods

This was a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial on 30 consecutive women undergoing bilateral reduction mammoplasty. On one side the wound surfaces were moistened with 25 mg/ml tranexamic acid before closure, and placebo (saline) was used on the other side. Drain fluid production was measured for 24 h after surgery, and pain was measured after 3 and 24 h. Postoperative complications including infection, seroma, rebleeding and suture reactions were recorded.

Results

Topical application of tranexamic acid to the wound surface after reduction mammoplasty reduced drain fluid production by 39 per cent (median 12·5 (range 0–44) versus 20·5 (0–100) ml; P = 0·038). Adverse effects were not observed. There were no significant differences in postoperative pain scores or complications.

Conclusion

Topical application of dilute tranexamic acid reduced bleeding in this model. The study adds to the evidence that this simple procedure may reduce wound bleeding after surgery. Registration number: NCT01964781 (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Introduction

When fibrinolysis exceeds coagulation, unwanted surgical bleeding may occur despite adequate haemostasis. Tranexamic acid is the most commonly used medication to prevent fibrinolysis. It acts by blocking the lysine-binding sites on plasminogen, thereby preventing the activation of plasminogen to plasmin1. Tranexamic acid can be administered orally or intravenously, but topical use is being reported increasingly.

Intravenous administration of tranexamic acid during major surgery has been shown to reduce the need for blood transfusion by 32–37 per cent, as well as measurable postoperative bleeding by 34 per cent2,3. The dose has varied considerably4, from 1 to 20 g administered intravenously over 20 min to 12 h. Suggested single intravenous doses are 1–2 g2,5,6. The minimal effective plasma concentration is unknown5,7–9. Safety concerns have included thrombosis, renal impairment, and increased risk of seizures associated with high doses (above 2 g)4,10. Definitive causal relationships have not been established4,11,12 but, as adverse effects may be dose-related, and doses above 1–2 g seem to provide no added benefit, high-dose intravenous administration is discouraged. Because of uncertainty about the effect of tranexamic acid, particularly on vascular occlusive events, it is still not recommended for routine use during most surgical procedures13.

Topical application of tranexamic acid provides a high drug concentration at the site of the wound and a low systemic concentration14,15. Studies from cardiac and orthopaedic surgery have shown an equal or superior effect of topical compared with intravenous tranexamic acid on both bleeding and transfusion requirement16–20. Topical treatment is cost-effective21, and adverse effects or drug interactions have not been reported.

In previous studies, topical tranexamic acid was instilled mainly as a bolus into confined spaces such as a joint, the mediastinum or the pericardium20,22, or applied to accessible wounds using soaked gauze23–25. A few studies26–28 have described simple moistening of a wound surface. Whereas most topical haemostatic agents can cover only a small surface area29, tranexamic acid diluted in saline can moisten large areas, such as after massive weight loss surgery, or in patients with burns30,31.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether moistening a wound surface with tranexamic acid reduces bleeding. This hypothesis was tested in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study of women undergoing bilateral reduction mammoplasty, where effects of intervention on one breast can be evaluated by comparison with the other.

Methods

Consecutive women above 18 years of age undergoing bilateral reduction mammoplasty at the Department of Plastic Surgery, St Olav's University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway, were eligible for inclusion in the study. Exclusion criteria were: a history of any thromboembolic disease, pregnancy or severe co-morbidity (American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) fitness grade III or IV). Women using platelet-inhibiting drugs or anticoagulants were not excluded automatically. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion.

Randomization and masking

The women were randomized to receive topical tranexamic acid to one breast and placebo to the other after reduction mammoplasty. Randomization was performed electronically by the Unit of Applied Clinical Research at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU-Trondheim) (http://www.ntnu.edu/dmf/akf/randomisering). Sealed envelopes were prepared stating whether the right or left side was to receive tranexamic acid according to the randomization. All personnel involved in surgery and postoperative follow-up were blinded to the randomization. The randomization code was kept at the Unit of Applied Clinical Research and was not broken until 4 weeks after the last patient had been enrolled.

Intervention

As the specific mode of topical application of tranexamic acid has not been published previously, the concentration of tranexamic acid needed to achieve an antifibrinolytic effect was unknown. To ensure a sufficiently high concentration, the tranexamic acid was diluted only to a volume sufficient to moisten a fairly large wound surface32: 20 ml moistens at least 1500 cm2. On the morning of surgery, a nurse not involved in the procedure prepared two identical plastic bottles of 20 ml saline (0·9 per cent sodium chloride), marking them right and left. She then opened the sealed envelope with the patient's project identification number. On the side stated in the envelope, 5 ml saline was extracted from the bottle and replaced with 5 ml of 100 mg/ml tranexamic acid. The prepared solution thus contained 20 ml of 25 mg/ml tranexamic acid. The other bottle (placebo) received only an identical needle puncture. The solutions were colourless, so the two bottles looked identical apart from their right and left markings. The bottles were then brought to the operating theatre.

Two surgeons performed the operation, operating on one breast each. Equal amounts of local anaesthetic were injected into the breasts at the end of surgery in accordance with the hospital's prevailing routine for reduction mammoplasty (20 ml of 1 mg/ml lidocaine with 5 µg/ml adrenaline and 20 ml of 2·5 mg/ml bupivacaine (AstraZeneca, London, UK) diluted in 120 ml saline for each breast). After resecting the breast tissue, the surgeons switched sides to evaluate/improve haemostasis, thus securing homogeneous wounds and equivalent operating times. The weight of resected tissue was recorded. The contents of the appropriate bottles containing tranexamic acid or placebo were smeared on to the wound surfaces before closure, taking care not to use moist swabs or gloves on the opposite side. Vacuum drains (Exudrain™ FG 14; AstraZeneca) were placed symmetrically, the wounds were closed with standard subcutaneous and intracutaneous suturing, and standard compression garments were fitted. The patients received oral analgesics after surgery, but no routine thromboprophylaxis; this is standard practice after reduction mammoplasty at this hospital.

Follow-up

All women were interviewed by a nurse 3 and 24 h after surgery. Drain fluid volume was recorded 24 h after surgery, and drains were removed when production was below 40 ml per 24 h, according to hospital routine. Haematoma needing reoperation within 24 h was registered. All women also had an outpatient appointment with one of the surgeons 3 months later. The women were encouraged to contact the hospital if any complications occurred.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was drain fluid production in the first 24 h after surgery. The drain fluid was not analysed further. A secondary outcome was postoperative pain, which was registered for each breast both 3 and 24 h after surgery, using a visual analogue scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (unbearable). Medical and surgical serious adverse events were recorded at the scheduled follow-ups.

Statistical analysis

A 25 per cent difference in drain volume between treated and untreated wounds was considered clinically important. As each woman was her own control, using a paired-samples t test to detect a difference of 0·25, and a standard deviation of 0·4, α of 0·05 and power 0·80, a sample size of 23 was needed33. To ensure additional power when using non-parametric statistical tests34 and to counter unforeseen events, 30 women were included.

Descriptive data are presented as mean(s.d.) or median (range), as appropriate. Differences in drain fluid volume and pain between breasts were analysed using a paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Differences in categorical variables between groups were evaluated with Fisher's exact test. P < 0·050 was considered significant. All analyses were done using SPSS® version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

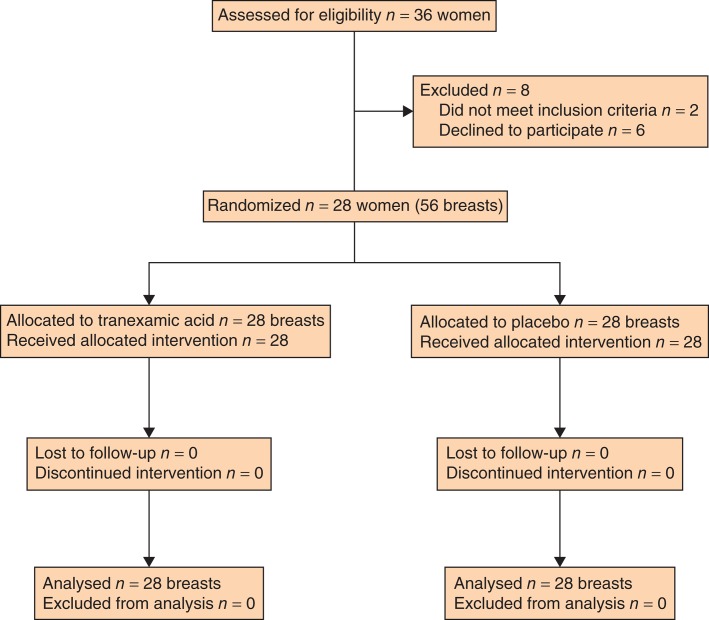

Of 36 women eligible for inclusion, six declined participation and 30 women were therefore enrolled. No patient withdrew after enrolment. Two were, however, excluded just before surgery (1 had a complete mastectomy instead of reduction mammoplasty; the other was recognized to have had a previous myocardial infarction and was considered ASA grade III). Tranexamic acid and placebo were not administered to these patients. Twenty-eight women remained eligible for final analyses (Fig. 1); their median age was 45 (18–67) years. None of the women used platelet inhibitors or anticoagulants. Mean resected tissue weight per breast was 415(162) g.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram for the study

Drain production was 39 per cent lower in breasts treated with tranexamic acid compared with breasts treated with placebo: median 12·5 (0–44) versus 20·5 (0–100) ml respectively (P = 0·038) (Table S1 and Fig. S1a, supporting information). To adjust for possible differences in wound surface areas owing to unequal size of the two breasts, a separate analysis was done with drain volume adjusted for resected weight. This analysis showed 42 per cent lower drain fluid production in breasts treated with tranexamic acid: median 12·9 (0–47) versus 22·0 (0–100) ml respectively (P = 0·017) (Table S1 and Fig. S1b, supporting information). Only one of 28 breasts treated with tranexamic acid produced 40 ml or more of fluid (44 ml), compared with nine of 28 placebo-treated breasts (P = 0·016). Two of these in the placebo group required reoperation and evacuation of haematoma.

Pain scores were similar in breasts treated with tranexamic acid or placebo on the day of surgery (median 2·5 (0–6) versus 2·0 (0–6); P = 0·179) and after 24 h (2·0 (0–6) versus 2·0 (0–5·5) respectively; P = 0·428).

No adverse effects were recorded after topical tranexamic acid. Five patients had a wound infection treated with antibiotics or outpatient wound drainage within 6 weeks of surgery. Another six women had a superficial inflammatory reaction related to the sutures. These had no relation to treatment with tranexamic acid or placebo. One woman had bilateral wound seromas which were evacuated.

Discussion

The present study showed that topical application of tranexamic acid significantly reduced wound drainage after reduction mammoplasty.

The main strength of the study is the model. Surface wounds can be diverse (burns, massive weight loss surgery), and it is challenging to design a study with equivalent wounds. Women undergoing bilateral reduction mammoplasty provide two almost identical wounds in an ordinary clinical setting. A small study can thus provide adequate statistical power.

The study, however, has several weaknesses. It was conducted using a surgical procedure that is not usually associated with major bleeding. Drain volumes, not blood loss, were measured; drain fluids consist of both blood and transudates, with a transition over time to more serous drain fluid. The breasts had also been injected with local anaesthetic containing adrenaline (epinephrine), but with equal volumes in each breast. The constituents of the drain fluids were not analysed, but registration took place during the first 24 h when the drainage is mostly blood. Whether topical tranexamic acid can influence transudate production or even seroma formation through its inhibition of fibrinolysis remains unknown.

The wounds after reduction mammoplasty are not completely identical, particularly when two surgeons operate, one side each. To correct for this, the surgeons undertook haemostasis on the contralateral side, and a separate analysis of drain volumes was done with adjustment for resected tissue weight.

Serum concentrations of tranexamic acid were not measured. Systemic absorption of topical tranexamic acid could in theory affect bleeding from the contralateral placebo wound. In vitro, a minimum concentration of 5–10 µg/ml is needed to inhibit fibrinolysis1,7. Studies in orthopaedic and cardiac surgery have found a negligible systemic concentration from application of boluses of tranexamic acid in confined spaces14,15. The tranexamic acid dose in the present study was 20 ml of 25 mg/ml, a total of 500 mg; this method should give a very low systemic concentration14,15.

The overall reduction in drain fluid production of about 40 per cent after topical administration of tranexamic acid here accords with previously published studies3,16–20, which consistently reported a reduction in transfusion need and measurable bleeding of between 30 and 40 per cent after both intravenous and topical tranexamic acid administration. There is little information on the concentration of tranexamic acid needed for topical effect. Instillation of a bolus of 1–3 g tranexamic acid diluted in 100 ml saline (concentration 10–30 mg/ml) has been studied in patients undergoing cardiac15,16 and orthopaedic17 surgery, whereas epistaxis has been treated with sponges moistened with undiluted tranexamic acid for intravenous use (100 mg/ml)23. This present study opted for a high concentration of 25 mg/ml, but still dilute enough to provide a volume sufficient to moisten large surface areas. There are few published studies where the mode of application was comparable to the moistening used in this study. A mouthwash containing 4·8 mg/ml tranexamic acid was effective after dental extraction28, whereas Hinder and Tschopp26 found no significant effect of gargling 1·7 mg/ml tranexamic acid solution after tonsillectomy. Athanasiadis and colleagues27 reported a significant effect after spraying the wound surfaces with tranexamic acid in endoscopic sinus surgery. The optimal concentration remains unknown.

The use of drains after reduction mammoplasty has little scientific evidence35 but is nevertheless common. At the time of study, the departmental routine was to use drains until fluid production was below 40 ml per 24 h. The present study suggests that topical tranexamic acid reduces drain fluid production after reduction mammoplasty to below this cut-off value in almost all patients, and may obviate the need for a drain.

There were two postoperative bleeds in the study, both in untreated breasts. The study was not powered to evaluate whether topical tranexamic acid could prevent postoperative haematoma. Ngaage and Bland4 reported that intravenous tranexamic acid reduced the risk of reoperation by 48 per cent after coronary surgery, and a significant reduction in rebleeding after tonsillectomy was described for the lysine analogue aminocaproic acid36. Few studies on tranexamic acid have reported rebleeding as an outcome measure3,37.

Tranexamic acid is inexpensive. Its cost-effectiveness has been thoroughly documented in orthopaedic surgery21. Even after operations where bleeding is less common, topical application of tranexamic acid may reduce the need for drains and outpatient visits. This simple method has potential for widespread application after surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank K. Fonstad for including all the patients in this study, I. Spets for randomization and preparation of drugs, and E. Saetnan, K. Sneve, C. Gonzales, H. Nordgaard and K. Gullestad for their contribution to the study. This research was conducted using funding from the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at St Olav's University Hospital.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Editor's comments

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1 Drain fluid production measured 24 h after surgery in patients undergoing bilateral reduction mammoplasty (Word document)

Fig. S1 a Drain fluid production measured 24 h after surgery and b drain fluid volume adjusted for resected tissue weight (Word document)

References

- 1.Dunn CJ, Goa KL. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in surgery and other indications. Drugs. 1999;57:1005–1032. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957060-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ker K, Prieto-Merino D, Roberts I. Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of tranexamic acid on surgical blood loss. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1271–1279. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ker K, Edwards P, Perel P, Shakur H, Roberts I. Effect of tranexamic acid on surgical bleeding: systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3054. e3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ngaage DL, Bland JM. Lessons from aprotinin: is the routine use and inconsistent dosing of tranexamic acid prudent? Meta-analysis of randomised and large matched observational studies. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:1375–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horrow JC, Van Riper DF, Strong MD, Grunewald KE, Parmet JL. The dose–response relationship of tranexamic acid. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:383–392. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199502000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, Danninger T, Mazumdar M, Opperer M, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349:g4829. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yee BE, Wissler RN, Zanghi CN, Feng C, Eaton MP. The effective concentration of tranexamic acid for inhibition of fibrinolysis in neonatal plasma in vitro. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:767–772. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a22258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson L, Eriksson O, Hedlund PO, Kjellman H, Lindqvist B. Special considerations with regard to the dosage of tranexamic acid in patients with chronic renal diseases. Urol Res. 1978;6:83–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00255578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowd NP, Karski JM, Cheng DC, Carroll JA, Lin Y, James RL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of tranexamic acid during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:390–399. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murkin JM, Falter F, Granton J, Young B, Burt C, Chu M. High-dose tranexamic acid is associated with nonischemic clinical seizures in cardiac surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:350–353. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c92b23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry DA, Carless PA, Moxey AJ, O'Connell D, Stokes BJ, Fergusson DA, et al. Anti-fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001886.pub4. CD001886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koster A, Schirmer U. Re-evaluation of the role of antifibrinolytic therapy with lysine analogs during cardiac surgery in the post aprotinin era. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24:92–97. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32833ff3eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ker K, Roberts I. Tranexamic acid for surgical bleeding. BMJ. 2014;349:g4934. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong J, Abrishami A, El Beheiry H, Mahomed NN, Roderick Davey J, Gandhi R, et al. Topical application of tranexamic acid reduces postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2503–2513. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Bonis M, Cavaliere F, Alessandrini F, Lapenna E, Santarelli F, Moscato U, et al. Topical use of tranexamic acid in coronary artery bypass operations: a double-blind, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:575–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(00)70139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ipema HJ, Tanzi MG. Use of topical tranexamic acid or aminocaproic acid to prevent bleeding after major surgical procedures. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:97–107. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:1937–1944. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wind TC, Barfield WR, Moskal JT. The effect of tranexamic acid on blood loss and transfusion rate in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1080–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Shen B, Zeng Y. Comparison of topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and prospective cohort trials. Knee. 2014;21:987–993. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alshryda S, Sukeik M, Sarda P, Blenkinsopp J, Haddad FS, Mason JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the topical administration of tranexamic acid in total hip and knee replacement. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-b:1005–1015. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B8.33745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuttle JR, Ritterman SA, Cassidy DB, Anazonwu WA, Froehlich JA, Rubin LE. Cost benefit analysis of topical tranexamic acid in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1512–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrishami A, Chung F, Wong J. Topical application of antifibrinolytic drugs for on-pump cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56:202–212. doi: 10.1007/s12630-008-9038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zahed R, Moharamzadeh P, Alizadeharasi S, Ghasemi A, Saeedi M. A new and rapid method for epistaxis treatment using injectable form of tranexamic acid topically: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1389–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarris I, Arafa A, Konaris L, Kadir RA. Topical use of tranexamic acid to control perioperative local bleeding in gynaecology patients with clotting disorders: two cases. Haemophilia. 2007;13:115–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang YM, Chapman TW, Brooks P. Use of tranexamic acid to reduce bleeding in burns surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:684–686. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinder D, Tschopp K. 2015;94:86–90. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1375656. [Topical application of tranexamic acid to prevent post-tonsillectomy haemorrhage.] Laryngorhinootologie. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Athanasiadis T, Beule AG, Wormald PJ. Effects of topical antifibrinolytics in endoscopic sinus surgery: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21:737–742. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patatanian E, Fugate SE. Hemostatic mouthwashes in anticoagulated patients undergoing dental extraction. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:2205–2210. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnard J, Millner R. A review of topical hemostatic agents for use in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterling JP, Heimbach DM. Hemostasis in burn surgery – a review. Burns. 2011;37:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh K, Nikkhah D, Dheansa B. What is the evidence for tranexamic acid in burns? Burns. 2014;40:1055–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kjersti A. 2015. 20 ml Fluid on AquaDoodle Canvas. https://youtu.be/10AkwMQSE1s [accessed 1 March ]

- 33.2012. Paired t-test. http://www.biomath.info/power/prt.htm [accessed 2 January]

- 34.Lehmann EL. Comparing two treatments of attributes in a population model. In: Lehmann EL, editor. Nonparametrics: Statistical Methods Based on Ranks. New York: Springer; 1998. pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stojkovic CA, Smeulders MJ, der Horst CM Van, Khan SM. Wound drainage after plastic and reconstructive surgery of the breast. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007258.pub2. CD007258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Overbosch HC, Hart HC. Local application of epsilon-aminocaproic acid (E.A.C.A.) in the prevention of haemorrhage after tonsillectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1970;84:905–908. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100072674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ker K, Beecher D, Roberts I. Topical application of tranexamic acid for the reduction of bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010562.pub2. CD010562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Drain fluid production measured 24 h after surgery in patients undergoing bilateral reduction mammoplasty (Word document)

Fig. S1 a Drain fluid production measured 24 h after surgery and b drain fluid volume adjusted for resected tissue weight (Word document)