Abstract

Objective

To determine whether (a) quality in schizophrenia care varies by race/ethnicity and over time and (b) these patterns differ across counties within states.

Data Sources

Medicaid claims data from California, Florida, New York, and North Carolina during 2002–2008.

Study Design

We studied black, Latino, and white Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Hierarchical regression models, by state, quantified person and county effects of race/ethnicity and year on a composite quality measure, adjusting for person-level characteristics.

Principal Findings

Overall, our cohort included 164,014 person-years (41–61 percent non-whites), corresponding to 98,400 beneficiaries. Relative to whites, quality was lower for blacks in every state and also lower for Latinos except in North Carolina. Temporal improvements were observed in California and North Carolina only. Within each state, counties differed in quality and disparities. Between-county variation in the black disparity was larger than between-county variation in the Latino disparity in California, and smaller in North Carolina; Latino disparities did not vary by county in Florida. In every state, counties differed in annual changes in quality; by 2008, no county had narrowed the initial disparities.

Conclusions

For Medicaid beneficiaries living in the same state, quality and disparities in schizophrenia care are influenced by county of residence for reasons beyond patients’ characteristics.

Keywords: Medicaid, schizophrenia, quality of care, racial/ethnic disparities, geographic variation

Medicaid is one of the largest components of state spending, accounting for nearly a quarter of total spending (National Association of State Budget Officers 2013). In response to recession-driven growth in Medicaid enrollment (Garfield and Young 2013) and steep reduction in state revenues, many states have recently made significant changes to their programs (Rowland 2009). Furthermore, under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), many states are pursuing Medicaid coverage expansions or taking up new options for Medicaid service delivery (Rudowitz et al. 2014). In this context of expansion and budget constraint, policy makers are exploring approaches to improving the value of Medicaid care, particularly for individuals with costly needs, and are focusing efforts on delivering quality services to enrollees (Mann 2013; Smith et al. 2014). Because these changes might be particularly beneficial to underserved populations, recent Medicaid reforms also provide an opportunity to address racial/ethnic disparities in care (Clemans-Cope et al. 2012). As states pursue these reforms, it is important to understand whether quality of care delivered to the most vulnerable Medicaid beneficiaries varies by race/ethnicity and place of residence.

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness associated with high levels of disability (Weinberger and Harrison 2011), and Medicaid is the primary source of health care coverage for individuals with the illness (Frank and Glied 2006). Despite extraordinary advances in schizophrenia therapeutics, too few in the United States have benefitted from this progress (Wang et al. 2008). Using a composite quality measure derived from 14 indicators, we assessed quality of mental health care received by Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia in California, Florida, New York, and North Carolina between 2002 and 2008, and found that quality of schizophrenia care was modest at best (Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2014). For example, the average North Carolina patient met about half of the individual indicators. Furthermore, we found substantial racial/ethnic disparities in quality of care: with the exception of Florida-based Latinos, quality was lower for blacks and Latinos than whites, with the size of these disparities varying across states (Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2014). However, it was not immediately clear whether these differences were uniform within states.

Extant evidence suggests that geography—including both state of residence and local factors—plays an important role in patterns of care, but most of this work has focused on the Medicare population (Institute of Medicine 2013). Although previous research indicates that state does play a role in the care received by Medicaid beneficiaries (Rubin et al. 2012; Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2014), much less is known about within-state variations in Medicaid care. Limited evidence suggests that care for fee-for-service Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia varies within states (Rascati et al. 2003; Kuno and Rothbard 2005; Liu et al. 2005; Horvitz-Lennon, Alegría, and Normand 2012). The drivers of such variation are poorly understood. While state policy explains some of the observed differences in patterns of care among states, state policy has a more limited effect on within-state variation because beneficiaries are covered by a single payment system with near identical policies and benefit structure. However, differences across counties in factors associated with quality and disparities in care may explain some of the observed within-state variations (Kuno and Rothbard 2005; Cummings et al. 2013).

The main goals of this study were to determine whether quality of care received by Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia between 2002 and 2008 varied among racial/ethnic groups and over time, and whether quality, racial/ethnic disparities, and annual changes in quality and disparities differed across counties within states. A secondary goal involved assessment of the associations between county characteristics and observed variations in quality of care. We focused on beneficiaries residing in California, Florida, New York, and North Carolina, four large and diverse states that account for about one-third of Medicaid beneficiaries nationwide.

Methods

Our primary outcome was a composite quality measure derived from 14 evidence-based indicators quantifying key processes of schizophrenia care. We examined variation in quality accounting for factors beyond the control of the health care system. Person-level and county-level differences in quality between minority and white patients reflected quality disparities while changes over time characterized temporal trends. Because our main interest was to assess variations in patterns of care between counties, the primary unit of analysis was the county. Data were assembled using person-year observations, the units of observations. Our explanatory analyses included county-level health care infrastructure and socioeconomic characteristics plausibly associated with quality of publicly funded care (Franzini and Spears 2003; Zuvekas and Taliaferro 2003; Kuno and Rothbard 2005; Subramanian et al. 2005; Smedley et al. 2008). We analyzed data separately for each state. The study was approved by the RAND IRB.

Data Sources and Study Population

We assembled Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) datasets from California, Florida, New York, and North Carolina for the period January 1, 2002, through December 31, 2009. MAX files contain information on Medicaid eligibility, demographic characteristics, diagnoses, and service utilization extracted from the states’ Medicaid Statistical Information System. For each continuously enrolled fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiary with schizophrenia of non-Latino white, non-Latino black, and Latino race/ethnicity, we assessed care over a 12-month period, creating person-year measures of quality. Person-year observations started on the date of the first claim (the index claim) having a schizophrenia diagnosis within each 12-month period; beneficiaries could contribute observations in each year between 2002 and 2008 (i.e., 1–7 years). MAX data for 2009 were used to ensure 12-month follow-up for person-years starting in 2008. We included all person-years for beneficiaries having at least 6 months of data preceding the index claim and valid county information. We focused on FFS beneficiaries because encounter data associated with services provided through managed care arrangements lack the completeness of FFS claims data. Beneficiaries with dual Medicaid–Medicare coverage were excluded because Medicare service use is not captured in the MAX data. Full details on the data and sample construction can be found elsewhere (Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2014).

Outcome Variable

Our primary outcome variable was a quality composite measure constructed from 14 evidence-based pharmacological, psychosocial, and appropriateness indicators of quality of schizophrenia care (West et al. 2005; Gilmer et al. 2007; Essock et al. 2009; Buchanan et al. 2010; Olfson, Marcus, and Doshi 2010). Pharmacological indicators included antipsychotic drug utilization, adherence, and polypharmacy avoidance; psychosocial indicators included utilization of psychosocial and psychotherapy services; and appropriateness indicators included continuity of care, routine utilization of outpatient psychiatric services, and avoidance of emergency department and inpatient services for schizophrenia (see Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2014 and Table A1 in Appendix SA2, for details on individual indicators). The composite measure was transformed to have a mean of 0, a standard deviation of 1, and scored such that higher values correspond to better quality of care. A composite score of 0 translates into having about half of the 14 evidence-based indicators met.

Independent Variables

Our primary independent variables included race/ethnicity and time; county characteristics were of secondary interest. All analyses adjusted for several person-level variables. We focused on non-Latino whites, non-Latino blacks, and Latinos, excluding beneficiaries of other race/ethnicity due to small numbers. For beneficiaries contributing observations in 2 or more years, we systematically reclassified race/ethnicity for those classified as Multiple Race or Unknown in some but not all years, and for those whose classification changed over time (see Appendix SA2 for details).

We operationalized time as the calendar year associated with the index claim of the person-year observation. We coded year as a count ranging from 0 to 6, where 0 indicated person-year observations with index claims in 2002. Time was treated as a continuous variable.

We identified counties based on five-digit Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) codes and assigned beneficiaries to the county associated with their index claim. We used the 2007, 2008, and 2010 Area Resource File data to construct the following county-level variables: number per 1,000 population of federally qualified health centers, hospital beds, psychiatrists, and psychiatric state hospitals; an indicator of partial or full shortage of mental health professionals; mean poverty rate; and percentage of whites, an indicator of the county's racial/ethnic composition. Although population density has been found to be related to access to community-based mental health services for Medicaid beneficiaries (Cummings et al. 2013), we dropped the variable from our analyses due to its high correlation with other county variables (e.g., the number of psychiatrists). Because there is evidence that quality of physical health care for blacks drops when the proportion of minorities increases (Baicker, Chandra, and Skinner 2005), we also computed the fraction of person-years associated with black and with Latino observations within each county.

We created adjustor variables measuring factors beyond the control of the health care system that might unduly influence the composite measure. We focused on person-level characteristics that may affect measured quality through their association with patients’ adherence to recommended treatment. These included sex, age, and eight health status variables constructed with data from the 6-month period preceding the index claim. The health status variables were an indicator of disability (whether the beneficiary ever had Supplemental Security Income [SSI] as a basis for Medicaid eligibility); several comorbidity indicators (vascular-metabolic, other chronic medical, dementia and other neurological, psychiatric, and substance use disorder); and two indicators of acute-care utilization (mean inpatient days for schizophrenia and two or more emergency department visits for schizophrenia).

Statistical Analyses

We estimated hierarchical linear regression models that linked the person-year composite score to race/ethnicity, year, and the interaction of race/ethnicity and year. The models were estimated separately for each state. The hierarchical model permitted separate estimates of average race/ethnicity and year effects from county-specific effects and made it possible to include all counties with at least one person-year observation through the inclusion of random regression coefficients. We rescaled the race/ethnicity variables to be centered about their county-specific means. In a first set of models, only person-level covariates were included. The intercepts (representing average county quality for white persons in 2002), race/ethnicity coefficients (representing county disparities), and year coefficients (representing county annual changes in quality) were assumed to vary across counties (see Statistical Note in Appendix SA2). The variance components associated with the random intercepts, race/ethnicity effects, and year effects provide an estimate of between-county variation. In a second set of hierarchical regression models, we added county health care infrastructure and socioeconomic characteristics as well as terms reflecting the county-specific fractions of black and Latino person-year observations. The county-specific race/ethnicity terms were centered about their state-level averages.

Person-level adjustors were included in all models. The best-fitting models were selected as those with the smallest Akaike Information Criterion values.

We examined the magnitudes and statistical significances of the race/ethnicity, year, and county characteristic regression coefficients. Race/ethnicity coefficients associated with person-level race/ethnicity variables different from 0 indicate a disparity in quality relative to whites. A year coefficient different from 0 indicates an annual change in quality. Race/ethnicity coefficients associated with the county-level race/ethnicity variables different from 0 represent county contextual effects. For example, a positive coefficient for the fraction of black person-years in the county implies that counties with more black person-years than the state average have a larger disparity relative to counties with fewer black person-years. We used a significance level of .05.

To determine whether quality, racial/ethnic disparities, or temporal changes differed across counties, we examined the statistical significance of the associated variance components. For example, a statistically significant black variance component implies the black disparity, defined as the average quality for blacks minus the average quality for whites, differs significantly across counties. Because of reliance on large sample approximations used in tests of variance components and their skewed distributions, we used a significance level of .10.

To quantify the impact of county on average quality, disparity, and temporal effects, we determined the expected difference in quality, disparity, and change in quality and disparity for a person residing in a moderately high-performing county compared to a similar person residing in a moderately low-performing county (Spiegelhalter, Abrams, and Myles 2004). We defined moderately high-performing counties for each effect as counties one standard deviation above the state mean and moderately low-performing counties as counties one standard deviation below the state mean (see Statistical Note in Appendix SA2).

All models were estimated using SAS 9.4 (SAS Corp., Cary, NC, USA). Due to the large number of person-years in all states except North Carolina, we randomly sampled person-year observations in the largest county to reduce the computational burden.

Results

Characteristics of Subjects and Counties Where They Live

Our cohort comprised 98,400 persons with schizophrenia across the four states, totaling 164,014 person-years of Medicaid care during the period 2002–2008 (Table1). The high rates of documented comorbidities in our study population are consistent with the high burden of disease typical of this population. All state cohorts were racially/ethnically diverse, with North Carolina having the largest minority representation that was majority black.

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics, by State (2002–2008)

| State | California | Florida | New York | North Carolina |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number person-years | 75,827 | 12,506 | 43,579 | 32,102 |

| Number of counties | 58 | 67 | 58 | 100 |

| Black, Latino, white, % | 25, 16, 59 | 36, 17, 47 | 33, 14, 53 | 60,1, 39 |

| Female, % | 44 | 49 | 47 | 54 |

| Mean age ± SD | 43.3 ± 11.4 | 41.9 ± 12.1 | 43.7 ± 11.2 | 42.0 ± 12.1 |

| Comorbidity in prior 6 months*, % | ||||

| Ever SSI | 99 | 98 | 95 | 96 |

| Vascular-metabolic comorbidities | 41 | 34 | 46 | 50 |

| Other chronic medical comorbidities | 31 | 27 | 28 | 26 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | 31 | 30 | 36 | 40 |

| Neurological comorbidities | 5.9 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 12 |

| Substance use disorders | 12 | 7.2 | 17 | 15 |

| Mean inpatient days ± SD | 1.1 ± 6.11 | 1.4 ± 8.88 | 2.4 ± 11.8 | 0.83 ± 4.27 |

| ≥2 Emergency department visits | 1.47 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.78 |

Defined as the 6-month period of uninterrupted FFS enrollment preceding the first schizophrenia claim.

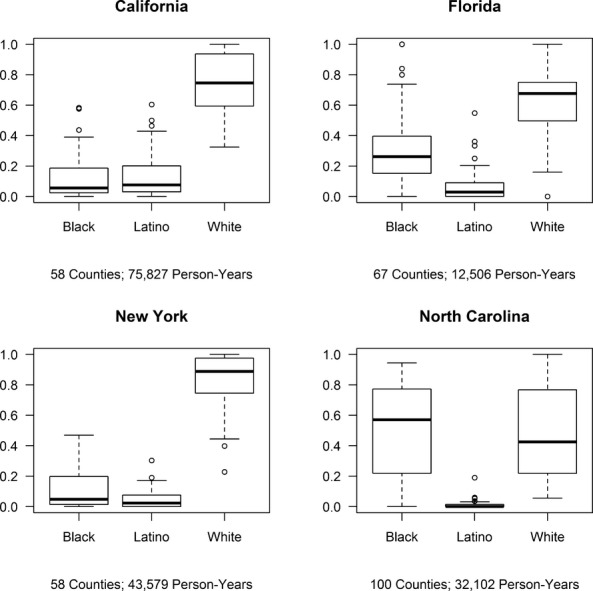

In all, there were 283 counties across the four study states: 58 in California, 67 in Florida, 58 in New York, and 100 in North Carolina. Counties differed in the racial/ethnic composition of person-years of schizophrenia care (Figure1). While 50 percent of North Carolina counties included no Latino observations, only 14 percent of California counties included no Latino observations. Six percent of Florida counties and 7 percent of North Carolina counties included no black observations. The proportions of California and New York counties with no black observations were at least twice as large, 16 percent and 14 percent, respectively. Nearly one-half (48 percent) of New York counties had more than 90 percent of white observations.

Figure 1.

County Distributions of Fraction of Black, Latino, and White Person-Years, by State (2002–2008)

The mean number of person-years of schizophrenia care per county varied across states, and counties also differed in characteristics potentially associated with patterns of Medicaid care (see Table A2 in Appendix SA2).

Quality and Variations in Schizophrenia Care

Principal Findings

The best-fitting model for each state included person-year race/ethnicity and year, with county-random intercepts, race/ethnicity effects, and year effects. Regardless of state, quality of care was lower for blacks than whites, with the mean black–white [95 percent CI] quality difference ranging from −0.53 [−0.68, −0.38] in California to −0.39 [−0.47, −0.31] in New York (Table2). Quality for Latinos was lower than whites in California, Florida, and New York, with mean differences ranging from −0.31 [−0.39, −0.23] in California to −0.20 [−0.30, −0.10] in New York, but in those states, the Latino disparity was smaller than the black disparity. Statistically significant but small annual improvements in quality were observed in California (0.038 per year [0.025, .0051]) and in North Carolina (0.010 per year [0, 0.021]). Between 2002 and 2008 in California, this corresponded to an improvement of 0.23 points in quality or an average increase of 3.9 percent of the indicators met. The sizes of the disparities did not change over time in any of the states.

Table 2.

Estimated Effects of Person-Level Race/Ethnicity and Time

| State | California | Florida | New York | North Carolina |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of counties | 58 | 67 | 58 | 100 |

| Number of person-years | 75,827 | 12,506 | 43,579 | 32,102 |

| Effect | Estimate (standard error) | |||

| Intercept | 0.32 (0.0540) | −0.44 (0.0575) | −0.38 (0.0369) | −0.81 (0.0424) |

| Black* | −0.53 (0.0744) | −0.41 (0.0522) | −0.39 (0.0422) | −0.47 (0.0332) |

| Latino* | −0.31 (0.0427) | −0.23 (0.0789) | −0.20 (0.0491) | 0.029 (0.125)† |

| Year | 0.038 (0.00670) | −0.0020 (0.0115)† | 0.0083 (0.00538)† | 0.010 (0.00523) |

| Variance | ||||

| Person-year (error) | 2.61 | 1.71 | 1.60 | 1.99 |

| County | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.85 | 0.39 |

Notes:Estimates are adjusted for person-level demographic and health status characteristics, and include county-random intercept, black, Latino, and year effects.

The black and Latino effects have been centered to county averages.

Effects are not significant at the .05 level.

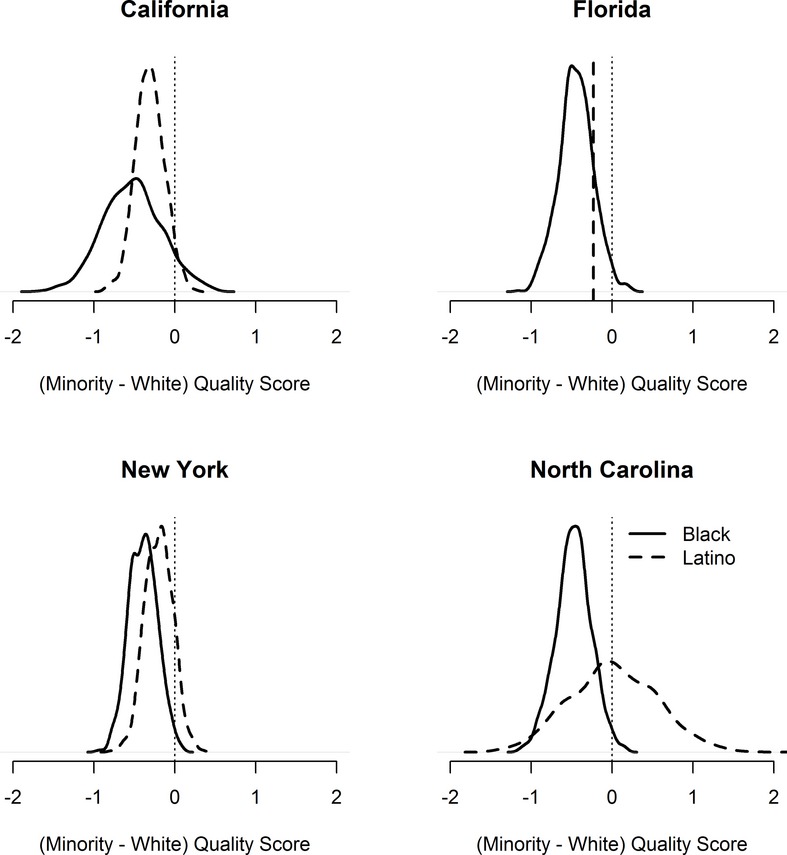

The between-county variation in quality ranged between 20 percent of the person-year variation in North Carolina and 5 percent for both New York and Florida. Within each state, counties differed in quality and disparities. In California, county differences in the black disparity were four times that for the Latino disparity (Figure2). The disparity for an average black patient residing in a moderately high-performing California county was 0.75 points smaller than for a similar patient residing in a moderately low-performing California county; for the average California Latino, the disparity was 0.37 points smaller in the moderately high-performing county compared to the lower performing county. In Florida, while Latino-white disparities in quality were uniform across counties, black–white disparities varied depending on overall quality. For example, for an average black patient residing in a high-performing Florida county, the black disparity was 0.44 points smaller compared to a similar patient residing in a moderately low-performing Florida county. In North Carolina, between-county variation in the black disparity was about one-tenth (0.15) the variation in the Latino disparity. The quality disparity for an average black or Latino patient residing in a high-performing New York county was 0.35 points smaller than a similar patient residing in a lower performing New York county. The fraction of minorities in each county was not related to quality, the size of the disparities, or temporal changes in quality in any state.

Figure 2.

- Note. Dashed vertical line at zero indicates no disparity in average quality.

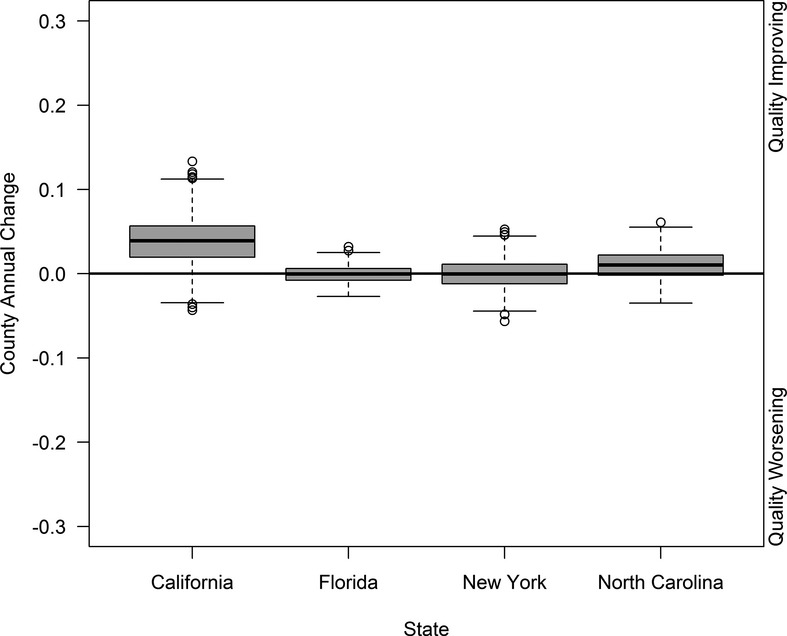

Temporal changes in quality also differed across counties in every state. While no statistically significant annual changes in quality at the person-year level were observed in Florida and New York, some counties in those states did exhibit some improvements (Figure3). In California, the difference in annual changes in quality between moderately high- and low-performing counties was 0.040 per year. By 2008, no county had narrowed the initial disparities.

Figure 3.

Distribution of County Annual Changes in Quality, by State (2002–2008)

Secondary Findings

The inclusion of Area Resource File-constructed county variables explained virtually none of the observed differences in quality among counties.

Discussion

We examined whether quality of mental health care received by Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia between 2002 and 2008 varied by race/ethnicity and over time, and whether these patterns differed across counties within states. We confirmed previous findings of racial/ethnic disparities in quality and variation among states in the size of the disparities and the likelihood of improvements in quality over time (Weissman, Vogeli, and Levy 2013; Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2014). In addition, we found substantial variation in quality and disparities across counties within states, and in the extent to which quality improved over the study period. We did not find within-state variation in temporal trends in disparities as no county narrowed the initial disparities. Hence, for Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia living in the same state, county of residence matters in terms of quality of care received, whether racial/ethnic disparities in quality exist, and whether quality improves over time.

While geographic variation in health care utilization, quality, disparities, and spending has been well-documented in Medicare for more than four decades (Institute of Medicine 2013), far less is known about geographic variations in the care of Medicaid beneficiaries, particularly as it pertains to within-state variation in patterns of serious mental illness care. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to document between-county differences in the care of a seriously mentally ill Medicaid population, thus providing further evidence of the importance of factors other than payer source in system performance (Lipson et al. 2010; Weissman, Vogeli, and Levy 2013).

We did not find evidence that within-state differences in quality were driven by differences in county characteristics plausibly associated with quality of publicly funded care. This finding is counter to that of a smaller study of Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia residing in a large urban center, which reported that quality of care was associated with the income characteristics of the catchment area where care was delivered (Kuno and Rothbard 2005). Although our different results may stem from methodological differences, it is possible that our socioeconomic variables failed to capture some important characteristics of the areas where Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia live and receive care. In addition and counter to other evidence pertaining to physical health care (Baicker, Chandra, and Skinner 2005), we did not find that the proportion of black or Latino beneficiaries with schizophrenia in the county influenced the size of the county black or Latino disparities.

Given that our measurable county characteristics did not explain our findings, what could be driving within-state variation in patterns of schizophrenia care? Policy differences may exist across counties within state Medicaid programs where counties have significant autonomy to design and implement policy. Although autonomy varied among our study states (e.g., low in New York and high in California), we were unable to measure county policies on observed variations. Variation in other dimensions may also explain the observed within-state differences (Landon, Wilson, and Cleary 1998; Cabana et al. 1999; Zuvekas and Taliaferro 2003; Drake, Skinner, and Goldman 2008; Horvitz-Lennon et al. 2009; Cummings et al. 2013). Beyond clinician availability, clinician knowledge and attitudes may vary among localities. The structure of the local health care system—such as the availability and organization of safety net or other Medicaid-accepting health care providers—could also be a factor, as could the availability of community-based services (e.g., through Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services [HCBS] waivers). Last, localities vary in their general policy environment (e.g., some counties may provide direct county funding of community-based services of relevance to people with serious mental illnesses and minorities) and in the strength of private sector initiatives such as patient advocacy and intensity of pharmaceutical promotion.

While we were unable to identify drivers of the observed within-state variation, our findings have important policy implications for state Medicaid programs and future research in this area. States are undertaking a host of initiatives to improve quality and value of care for high-need and costly populations. While most Medicaid policy decisions are, by federal law, statewide, there are ways that states can target efforts within Medicaid to address county variation. After identifying which localities have the largest quality or disparity problems, states could undertake a targeted evaluation of the factors driving their lower performance relative to other areas in the state. Because relevant county-level characteristics may not be captured by existing data, qualitative work may be a promising approach to this effort.

Once target localities and drivers are identified, state policy makers have several options to target counties with the greatest need for improvement in quality or disparities with the goal of bringing these localities to the level of the higher performing counties in the state. For example, when implementing statewide performance-improvement initiatives, states may provide more resources and monitor outcomes more closely in low-performing counties. Those counties may be targeted for demonstrations or HCBS programs aimed at improving serious mental illness care. States might also consider providing additional resources to safety net facilities serving high numbers of Medicaid patients in the targeted counties, whether in the form of technical assistance or additional funds for expanding and improving the quality of the mental health workforce in those facilities. In addition, states might set up statewide learning collaboratives through which high-performing counties could share their experience. Lastly, states could target efforts through pathways other than Medicaid—such as state mental health agency budgets or public health functions—that are not bound by federal rules regarding statewideness.

Our study has some limitations. Although the study states represent one-third of all Medicaid beneficiaries in the United States, findings may not be generalized beyond these states or beyond FFS beneficiaries living in those states. Second, like any observational study, unmeasured variables may confound the association between race/ethnicity and quality of care. Third, because race/ethnicity coded in claims data may be inaccurate (Parekh, Kronick, and Tavenner 2014), we have some minor misclassification in our racial/ethnic groups. We attempted to minimize this error by utilizing longitudinal information from all claims for an individual. Fourth, county-level variables constructed with the Area Resource File represent a county average; hence, they may not fully describe the particular geographic area where Medicaid beneficiaries resided and received care during the study period. Fifth, we ignored the correlation induced by multiple observations for an individual. Ideally, an additional random person effect would be included in the model but the computational burden of three levels of nesting was prohibitive. Last, the policy context has changed as the data were collected as a result of the implementation of the ACA. However, most of the recent changes in Medicaid occurred in populations not included in these analyses and, in addition, we are not aware of any major policy changes related to quality of schizophrenia care in the study states that have occurred since these data were collected.

Conclusion

At a time of unprecedented expansion of the Medicaid program and rekindled interest in understanding its health impacts (Garfield and Damico 2012; Sommers, Baicker, and Epstein 2012; Baicker et al. 2013), efforts are underway to improve quality and narrow racial/ethnic disparities in Medicaid care. Our study quantified and sought to explain local variation in Medicaid care delivered to disabled beneficiaries, an extremely relevant exercise at a time when program expansions have focused attention on the need for states to monitor variation in beneficiaries’ health care experience.

Quality and disparities in the care received by Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia vary within states, confirming for this population what has been known for others: place of residence matters in terms of quality and racial/ethnic disparities in care. Although quality improved in many counties between 2002 and 2008, no county narrowed the initial disparities in quality, underscoring the enormity of the challenge of eradicating racial/ethnic disparities in serious mental illness care.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This research was supported by R01 MH087488 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Additional Information.

References

- Baicker K, Chandra A. Skinner JS. Geographic Variation in Health Care and the Problem of Measuring Racial Disparities. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2005;48(1 Suppl):S42–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, Bernstein M, Gruber JH, Newhouse JP, Schneider EC, Wright BJ, Zaslavsky AM, Finkelstein AN, Carlson M, Edlund T, Gallia C. Smith J. The Oregon Experiment-Effects of Medicaid on Clinical Outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(18):1713–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, Himelhoch S, Fang B, Peterson E, Aquino PR. Keller W. The 2009 Schizophrenia Port Psychopharmacological Treatment Recommendations and Summary Statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36(1):71–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud P-AC. Rubin HR. Why Don't Physicians Follow Clinical Practice Guidelines? A Framework for Improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(15):1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemans-Cope L, Kenney GM, Buettgens M, Carroll C. Blavin F. The Affordable Care Act's Coverage Expansions Will Reduce Differences in Uninsurance Rates by Race and Ethnicity. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2012;31(5):920–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JR, Wen H, Ko M. Druss BG. Geography and the Medicaid Mental Health Care Infrastructure: Implications for Health Care Reform. Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry. 2013;70(10):1084–90. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake R, Skinner J. Goldman HH. What Explains the Diffusion of Treatments for Mental Illness? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1385–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essock SM, Covell NH, Leckman-Westin E, Lieberman JA, Sederer LI, Kealey E. Finnerty MT. Identifying Clinically Questionable Psychotropic Prescribing Practices for Medicaid Recipients in New York State. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(12):1595–602. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank RG. Glied SA. Better But Not Well: Mental Health Policy in the U.S. since 1950. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Franzini L. Spears W. Contributions of Social Context to Inequalities in Years of Life Lost to Heart Disease in Texas, U.S.A. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57(10):1847–61. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield RL. Damico A. Medicaid Expansion under Health Reform May Increase Service Use and Improve Access for Low-Income Adults with Diabetes. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2012;31(1):159–67. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield R. Young K. Enrollment-Driven Expenditure Growth: Medicaid Spending During the Economic Downturn, FY 2007–2011. Washington, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Folsom DP, Mastin W. Jeste DV. Antipsychotic Polypharmacy Trends among Medi-Cal Beneficiaries with Schizophrenia in San Diego County, 1999-2004. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(7):1007–10. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz-Lennon M, Alegría M. Normand S-LT. The Effect of Race-Ethnicity and Geography on Adoption of Innovations in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(12):1171–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz-Lennon M, Donohue JM, Domino ME. Normand SLT. Improving Quality and Diffusing Best Practices: The Case of Schizophrenia. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2009;28(3):701–12. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz-Lennon M, Volya R, Donohue JM, Lave JR, Stein BD. Normand S-LT. Disparities in Quality of Care among Publicly Insured Adults with Schizophrenia in Four Large U.S. States, 2002-2008. Health Services Research. 2014;49(4):1121–44. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Variation in Health Care Spending: Target Decision Making, Not Geography. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno E. Rothbard AB. The Effect of Income and Race on Quality of Psychiatric Care in Community Mental Health Centers. Community Mental Health Journal. 2005;41(5):613–22. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-6365-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon BE, Wilson IB. Cleary PD. A Conceptual Model of the Effects of Health Care Organizations on the Quality of Medical Care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(17):1377–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipson D, Colby M, Lake T, Liu S. Turchin S. Value for the Money Spent? Exploring the Relationship between Medicaid Costs and Quality. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu GG, Sun SX, Christensen DB. Zhao Z. Choice of Atypical Antipsychotic Therapy for Patients with Schizophrenia: An Analysis of a Medicaid Population. Current Therapeutic Research. 2005;66(5):463–74. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann C. CMCS Informational Bulletin: Targeting Medicaid Super-Utilizers to Decrease Costs and Improve Quality. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of State Budget Officers. State Expenditure Report (Fiscal 2011–2013 Data) Washington, DC: National Association of State Budget Officers; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC. Doshi JA. Continuity of Care after Inpatient Discharge of Patients with Schizophrenia in the Medicaid Program: A Retrospective Longitudinal Cohort Analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(7):831–8. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m05969yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AK, Kronick R. Tavenner M. Optimizing Health for Persons with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312(12):1199–200. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascati KL, Johnsrud MT, Crismon ML, Lage MJ. Barber BL. Olanzapine versus Risperidone in the Treatment of Schizophrenia : A Comparison of Costs among Texas Medicaid Recipients. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21(10):683–97. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200321100-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland D. Health Care and Medicaid—Weathering the Recession. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(13):1273–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0901072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin D, Matone M, Huang Y-S, dosReis S, Feudtner C. Localio R. Interstate Variation in Trends of Psychotropic Medication Use among Medicaid-Enrolled Children in Foster Care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(8):1492–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rudowitz R, Snyder L, Smith VK, Gifford K. Ellis E. Implementing the Aca: Medicaid Spending & Enrollment Growth for FY 2014 and FY 2015. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley B, Alvarez B, Panares R, Fish-Parcham C. Adland S. Identifying and Evaluating Equity Provisions in State Health Care Reform. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith VK, Gifford K, Ellis E, Rudowitz R. Snyder L. Medicaid in an Era of Health & Delivery System Reform: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2014 and 2015. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sommers BD, Baicker K. Epstein AM. Mortality and Access to Care among Adults after State Medicaid Expansions. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(11):1025–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter DJ, Abrams KR. Myles JP. Bayesian Approaches to Clinical Trials and Health-Care Evaluation. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Chen JT, Rehkopf DH, Waterman PD. Krieger N. Racial Disparities in Context: A Multilevel Analysis of Neighborhood Variations in Poverty and Excess Mortality among Black Populations in Massachusetts. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(2):260–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.034132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Heinssen R, Oliveri M, Wagner A. Goodman W. Bridging Bench and Practice: Translational Research for Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;34(1):204–12. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger DR. Harrison PJ. Schizophrenia. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman JS, Vogeli C. Levy DE. The Quality of Hospital Care for Medicaid and Private Pay Patients. Medical Care. 2013;51(5):389–95. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827fef95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JC, Wilk JE, Olfson M, Rae DS, Marcus S, Narrow WE, Pincus HA. Regier DA. Patterns and Quality of Treatment for Patients with Schizophrenia in Routine Psychiatric Practice. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(3):283–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH. Taliaferro GS. Pathways to Access: Health Insurance, the Health Care Delivery System, and Racial/Ethnic Disparities, 1996-1999. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2003;22(2):139–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Additional Information.