Abstract

The aim of the present study was to determine the impact of α5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunit deletion in the mouse on the development and intensity of nociceptive behavior in various chronic pain models.

The role of α5-containing nAChRs was explored in mouse models of chronic pain, including peripheral neuropathy (chronic constriction nerve injury, CCI), tonic inflammatory pain (the formalin test) and short and long-term inflammatory pain (complete Freund’s adjuvant, CFA and carrageenan tests) in α5 knock-out (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice.

The results showed that paw-licking time was decreased in the formalin test, and the hyperalgesic and allodynic responses to carrageenan and CFA injections were also reduced. In addition, paw edema in formalin-, carrageenan- or CFA-treated mice were attenuated in α5-KO mice significantly. Furthermore, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) levels of carrageenan-treated paws were lower in α5-KO mice. The antinociceptive effects of nicotine and sazetidine-A but not varenicline were α5-dependent in the formalin test. Both hyperalgesia and allodynia observed in the CCI test were reduced in α5-KO mice. Nicotine reversal of mechanical allodynia in the CCI test was mediated through α5-nAChRs at spinal and peripheral sites.

In summary, our results highlight the involvement of the α5 nAChR subunit in the development of hyperalgesia, allodynia and inflammation associated with chronic neuropathic and inflammatory pain models. They also suggest the importance of α5-nAChRs as a target for the treatment of chronic pain.

Keywords: alpha 5, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, neuropathic pain, inflammatory pain

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels that exist as homomeric or heteromeric complexes of α and β subunits. To date, 12 neuronal subunits (α2-α10 and β2-β4) have been identified in mammals [1]. The α5 nAChR subunits are widely expressed in the mammalian central nervous system [2], including the spinal cord [3], rat dorsal root ganglia [4], as well as peripherally in sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia [5].

The α5 subunit cannot form a functional homomeric receptor, or assemble in nAChRs as the sole α subunit expressed with either β2 or β4. Therefore, the α5 subunit is incorporated into α4β2*, α3β2*, and α3β4* nAChRs (where * denotes the possible inclusion of additional nAChR subunits) where it greatly influences nicotine’s modulation of receptor function and pharmacological properties of these receptor subtypes in response to the drug in heterologous expression systems [6–8]. Furthermore, recent data support an important role for α5 in nicotine’s behavioral effects. Mice null for the α5 nAChR subunit have reduced sensitivity to nicotine-induced seizures and hypolocomotion [9,10]. Additionally, these α5 KO mice are less sensitive to nicotine-induced antinociception and hypothermia compared to WT littermates after acute administration of the drug in mice [11,12]. Interestingly, α5 KO mice showed an enhancement of nicotine reward and intake [11,13].

Data is also emerging on the possible role of α5-containing nAChRs in the regulation of important functions in the central nervous system as well as the peripheral nervous system. For example, these receptors were reported to influence the autonomic control of several organ systems [14]. Furthermore, Vincler and Eisenach (2004) observed an increased expression of the α5 nAChR subunit in the outer laminae of the dorsal horn following spinal nerve ligation in rats [3]. More recently, the same group reported that intrathecal injection of α5 antisense oligonucleotides to rats with spinal nerve ligation alleviated the mechanical allodynia in the animals [15]. In addition, treatment of these rats with α5-antisense was accompanied with a significant reduction in pCREB immunoreactivity in the outer laminae of the dorsal horn of the ligated rats. We therefore hypothesized that disruption of α5 nAChR subunit will modulate pain behaviors in chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain.

The present study seeks to determine the impact of α5 nAChR subunit deletion in the mouse on the development and intensity of nociceptive behavior in various chronic pain models. Using α5 knock-out (KO) mice, the role of α5-containing nAChRs was explored in well-established rodent models of chronic pain, such as peripheral neuropathy (chronic constriction nerve injury, CCI), tonic inflammatory pain (the formalin test) and short- and long-term inflammatory pain (carrageenan and complete Freund’s adjuvant- CFA tests). We also determined to what extent is the antinociceptive effects of nicotine, in some of these models, are mediated by α5-containing nAChRs. Data obtained from these studies will further the understanding of the α5 nAChR subunit in pain regulation and may lead to the development of α5-containing nAChR agonists for the treatment of chronic pain.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and were used only for backcrossing. Mice null for the α5 subunit and their wild-type littermates were bred in an animal care facility at Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond, VA) and are maintained on a C57Bl/6J background. They have been backcrossed to at least N12. For all experiments, mutants and wild type controls are obtained from crossing heterozygote mice. This breeding scheme allows us to rigorously control for any anomalies that may occur with crossing solely mutant animals. α5 KO mice were originally described by Salas et al. [10]. Male animals were 8–10 weeks of age at the start of the experiments and were group-housed in a 21°C humidity-controlled Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved animal care facility with ad libitum access to food and water. Experiments were performed during the light cycle and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University and conducted according to the guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the United States National Institutes of Health.

2.2. Drugs

(−)-Nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All drugs were dissolved in physiological saline (0.9% sodium chloride) and injected subcutaneously (s.c.) at a total volume of 1ml/100g body weight unless noted otherwise. Varenicline (7,8,9,10-tetrahydro- 6,10-methano- 6H-pyrazino (2,3-h)(3) benzazepine) and sazetidine-A (6-[5-[(2S)-2-Azetidinylmethoxy]-3-pyridinyl]-5-hexyn-1-ol) were supplied by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA Drug Supply Program, Bethesda, MD). All doses are expressed as the free base of the drug.

2.3. Behavioral Pain Tests

2.3.1. Formalin Test

The formalin test was carried out in an open Plexiglas cage, with a mirror placed at a 45 degree angle behind the cage to allow an unobstructed view of the paws. Mice were allowed to acclimate for 15 min in the test cage prior to injection. Each animal received an intraplantar injection of 20 μl of (2.5%) formalin to the right hindpaw. Each mouse was then immediately placed in a Plexiglas box. Up to two mice at one time were observed from 0 to 5 min (phase 1) and 20 to 45 min (phase 2) post-Formalin injection. The period between the two phases of nociceptive responding is generally considered to be a phase of weak activity. The amount of time spent licking the injected paw was recorded with a digital stopwatch. Paw diameter (see measurement of paw edema) was also measured before and 1 hr after formalin injection.

In a separate experiment, nicotinic analogs [nicotine (1.5 mg/kg), varenicline (3 mg/kg) and sazetidine-A (1.5 mg/kg)] or the control solution was injected s.c. 15 min before the formalin injection in α5 WT and KO mice. These active doses were selected based on our recent report in the same test [16]. All behavioral testing on WT and KO animals in this study was performed in a blinded manner.

2.3.2. Carrageenan-Induced Inflammatory Pain Model

α5 WT and KO mice were injected with 20 μl of (0.5%) of lambda-carrageenan in the intraplantar region of the right hindpaw. Paw diameter (see measurement of paw edema), thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia (see paw withdrawal test and von Frey test) were measured before and at several hourly time-points after lambda-carrageenan injection (3, 6 and 24 h).

2.3.3. Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA)-Induced Inflammatory Pain Model

α5 WT and KO mice were injected with 20 μl of CFA (50% for allodynia measures and 75% for hyperalgesia) in the intraplantar region of the right hindpaw. Paw diameter (see measurement of paw edema), thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia (see paw withdrawal test and von Frey test) were measured before and after CFA injection (day 3 and 14).

2.3.4. Measurement of Paw Edema

The thickness of the formalin, carrageenan, CFA treated and control paws were measured both before and after injections at the time points indicated above, using a digital caliper (Traceable Calipers, Friendswood, TX). Data were recorded to the nearest ±0.01 mm and expressed as change in paw thickness (ΔPD=difference in the ipsilateral paw diameter before and after injection paw thickness).

2.3.5. Chronic Constrictive Nerve Injury (CCI)-Induced Neuropathic Pain Model

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (45 mg/kg, i.p.). An incision was made just below the hip bone, parallel to the sciatic nerve. The right common sciatic nerve was exposed at the level proximal to the sciatic trifurcation and a nerve segment 3–5 mm long was separated from surrounding connective tissue. Two loose ligatures with 5-0 silk suture were made around the nerve with a 1.0–1.5 mm interval between each of them. Muscles were closed with suture thread and the wound with wound clips. This procedure resulted in chronic constrictive injury (CCI) of the ligated nerve. Thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia (see paw withdrawal test and von Frey test) were measured at several weekly time-points after operation (1, 3, and 7 weeks).

In a separate experimental group, nicotine (0.9 mg/kg) or vehicle were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) to α5 WT and KO mice 7 weeks after CCI surgery and tested for mechanical allodynia. Mechanical stimuli thresholds were determined for each animal 5, 10, 15, 30, and 60 min after injection of nicotine.

We also tested anti-allodynic effects of nicotine using different administration routes to understand its sites of action. Hence, we administered nicotine intracerebroventricularly (25 μg/5μl, i.c.v.) for central; intrathecally (20 μg/5μl, i.t.) for spinal/supraspinal and intraplantarly (45 μg/5μl, i.pl.) for peripheral sites of action in α5 WT and KO mice 2 weeks after CCI surgery. We chose the doses according to our previous results and dose-response curves determinations (data not shown).

2.3.6. Paw Withdrawal Test (Evaluation of Thermal Hyperalgesia)

Thermal hyperalgesia was measured via the Hargreaves test. Mice were placed in clear plastic chambers (7×9×10 cm) on an elevated surface and allowed to acclimate to their environment before testing. The radiant heat source was directed to the plantar surface of each hind paw in the area immediately proximal to the toes. The paw withdrawal latency (PWL) was defined as the time from the onset of radiant heat to withdrawal of the animal’s hind paw. A 20-sec cut-off time was used. Three measures of PWL were taken and averaged for each hind-paw using the Hargreaves test. Withdrawal latencies were measured in each hind paw. Results were expressed either as withdrawal latency for each paw or as ΔPWL (sec) = contralateral latency -ipsilateral latency.

2.3.7. Von Frey Test (Evaluation of Mechanical Allodynia)

Mechanical allodynia thresholds were determined according to the method of Chaplan et al. [17]. Mice were placed in a Plexiglas cage with mesh metal flooring and allowed to acclimate for 30 min before testing. A series of calibrated von Frey filaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) with logarithmically incremental stiffness ranging from 2.83 to 5.88 expressed as dsLog 10 of [10 £ force in (mg)] were applied to the paw with a modified up-down method [18]. In the absence of a paw withdrawal response to the initially selected filament, a thicker filament corresponding to a stronger stimulus was presented. In the event of paw withdrawal, the next weaker stimulus was chosen. Each hair was presented perpendicularly against the paw, with sufficient force to cause slight bending, and held 2–3 s. The stimulation of the same intensity was applied 5 times to the hind paw at intervals of a few seconds. The mechanical threshold was expressed as Log10 of [10 £ force in (mg)], indicating the force of the Von Frey hair to which the animal reacted (paw withdrawn, licking or shaking).

2.3.8. Acetic Acid-Induced Conditioned Place Aversion (CPA)

To evaluate the negative affective component of pain, the CPA test was performed. In brief, groups of α5 WT and KO mice (n= 6–8 per group) were handled for three days prior to initiation of CPA testing. The CPA apparatus consisted of a three-chambered box with a white compartment, a black compartment, and a center grey compartment. The black and white compartments had different floor textures to help the mice further differentiate between the two environments. On day 1, mice were placed in the grey center compartment for a 5 min habituation period, followed by a 15 min testing period where mice were free to explore all compartments to determine their baseline responses. A baseline score was recorded and used to randomly pair each mouse with either the black or white compartment. Drug-paired sides were randomized so that an even number of mice received drug on the black and white side. On day 2 (conditioning session), conditioning was performed as follows: the mice were given an i.p. injection of saline (10 ml/kg) as a control non-noxious stimulus or 1.2 % acetic acid (AA) (10 ml/kg) as a noxious stimulus and then immediately confined in the drug-paired compartment for 40 min. On test day (day 3), mice were allowed to freely explore all the compartments, and day 1 procedure was repeated. Data were expressed as time spent on the drug-paired side postconditioning minus time spent on the drug-paired side pre-conditioning. A positive number indicated a preference for the drug-paired side, whereas a negative number indicated an aversion to the drug-paired side. A number at or near zero indicated no preference for either side.

2.3.9. Locomotor Activity Test

Mice were placed into individual Omnitech (Columbus, OH) photocell activity cages (28 × 16.5 cm). Interruptions of the photocell beams (two banks of eight cells each), which assess walking and rearing, were then recorded for the next 30 min. Data were expressed as the number of photocell interruptions.

2.3.10. Motor Coordination

In order to measure motor coordination, we used the rotarod test (IITC Inc. Life Science). The animals were placed on textured drums (1¼ inch diameter) to avoid slipping. When an animal falls onto the individual sensing platforms, test results were recorded. Five mice were tested at a time using a rate of 4 rpm. Naive mice were trained until they remained on the rotarod for 5 min. If a mouse fell from the rotarod during this time period, it was scored as motor impaired. Percent impairment was calculated as follows: % impairment = [(180 − test time/180 * 100].

2.4. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha (TNF-α) Levels

The injected hind paw samples treated with either saline or carrageenan (0.5%) in α5 KO and WT mice were collected 6 hours after carrageenan injection and homogenized in 1 mL of Tris-HCl buffer containing protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA; P8340). Samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm at a temperature of 4°C for 30 minutes, and the supernatant was frozen at −80°C until the assay. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay [19]. TNF-α level (pg/mg protein) was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay commercial kit (Quantikine M murine; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

2.5. Intracerebroventricular and intrathecal injections

I.c.v. injections were performed according to the method of Pedigo et al. [20]. Mice were lightly anesthetized with ether and an incision was made in the scalp such that the bregma was exposed. Injections were performed using a 26 gauge needle with a sleeve of PE 20 tubing to control the depth of the injection. An injection volume of 5 μl was administered at a site 2 mm rostral and 2 mm caudal to the bregma at a depth of 2 mm. All experiments were conducted with the investigator blind to genotype and treatment. At the end of the study, animals were injected i.c.v. with 5 μl of cresyl violet dye, and were perfused to confirm drug diffusion into both the lateral ventricles.

I.t. injections were performed free-hand between the fifth and sixth lumbar vertebra in unanesthetized male mice according to the method of Hylden and Wilcox [21].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Pain behavioral data are presented as mean ± SEM. Allodynia over multiple minutes after nicotine injection in CCI mice were calculated as area under the curve (AUC) using the trapezoidal rule. For simple comparisons of two groups, a two-tailed student t test was used. Otherwise, statistical analysis was performed with mixed-factor ANOVA. Two-way ANOVAs were used to evaluate pain sensitivity at the different time points in different genotypes. Significant overall ANOVA are followed by Bonferroni’s or Student Newman Keuls post hoc test when appropriate. All differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. The GraphPad Prism program was used for data calculations, graphical representations, and statistical analysis (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

3. Results

3.1. Pain Behavior and Paw Edema in α5 Knockout Mice in The Formalin Test

First, we evaluated the paw licking response of α5 KO and WT mice (n=8/each group) in the formalin test at 2.5% concentration. No significant difference was found in phase I behaviors between WT and KO animals (Fig 1A). However, in the phase II response, there were significant reductions of pain behavior in α5 KO mice compared to WT mice [F(1,14)=32.278 p<0.001] (Fig 1A). Additionally, the changes of paw edema were measured in α5 WT and KO mice 1 hour after intraplantar injection of 2.5 % formalin. The degree of paw edema in α5 KO mice was significantly lower than WT littermate controls [t=5.842, df=14; p<0.001] (Fig 1B).

Fig. 1. Pain behavior and paw edema in α5 KO and WT mice in the formalin test.

The paw licking response after intraplantar injection of (A) 2.5% formalin concentration into the right paw of both α5 KO and their WT littermate mice. Changes in paw edema (B), as measured by the difference in the ipsilateral paw diameter before and after injection (ΔPD), in α5 WT and KO mice 1 hour after intraplantar injection of formalin. Data were given as the mean ± S.E.M. of 8 animals for each group. *p<0.05 significantly different from WT group.

3.2. Effect of Nicotine, Varenicline and Sazetidine-A in α5 Knockout Mice in The Formalin Test

We tested the effects of nicotine, varenicline and sazetidine-A in formalin test (2.5%) in α5 KO and WT mice (n=8/each group). All three drugs reduced significantly the paw licking time of phase I response [F(1,14)=18.92, F(1,14)=18.181 and F(1,14)=24.81; p<0.001 respectively] (Fig 2A) and phase II responses [F(1,14)=320.69, F(1,14)=61.792 and F(1,14)=335.338; p<0.001, respectively] (Fig 2B) in α5 WT mice. However, nicotine and sazetidine-A failed to show antinociception in phase I [F(1,14)=0.169 and F(1,14)=1.303, p>0.05 respectively] and phase II [F(1,14)=0.00618, p>0.05] responses in α5 KO mice (Fig 2A and B). In contrast to nicotine and sazetidine-A, varenicline showed antinociceptive effect in both phases in KO mice [F(1,14)=37.399 (phase I) and F(1,14)=48.351 (phase II) p<0.001].

Fig. 2. Effect of nicotine, varenicline and sazetidine-A in α5 KO and WT mice in the formalin test.

The effects of subcutaneous administration of nicotine (1.5 mg/kg), varenicline (3 mg/kg) and sazetidine-A (1.5 mg/kg) before intraplantar formalin (2.5 %) injection on paw licking time at phase I (A) and phase II (B) in the formalin test. Data were given as the mean ± S.E.M. of 8 animals for each group. *p<0.05 significantly different from corresponding vehicle and #p< 0.05 significantly different from corresponding WT group.

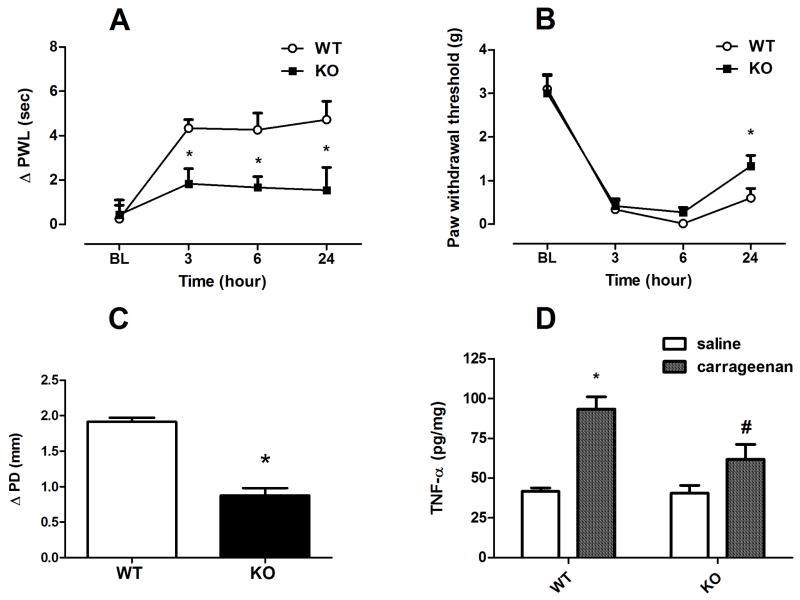

3.3. Hyperalgesia, Allodynia and Inflammation in α5 Knockout Mice in The Carrageenan Test

Mice (n=6/each group) were given an intraplantar injection of carrageenan (0.5%) and then tested for hyperalgesia and allodynia at 3, 6 and 24 h later. In addition, paw edema was measured 6 hours after injection of carrageenan. Prior to carrageenan injection, α5 KO and WT mice did not differ in heat and mechanical baselines (Fig. 3A & 3B). However, our results indicated that there is significant difference between WT and KO animals in development of carrageenan-induced inflammation as seen in the degree of paw edema [t=8.685, df=10; p<0.001] and hyperalgesic responses [F(1,10)=10.088; p<0.01 after 3 hr, F(1,10)=8.282; p<0.05 after 6 hr and F(1,10)=5.478; p<0.05 after 24 hr] (Fig. 3A, 3C). On the other hand, a significant reduction in mechanical allodynia response in the KO mice compared to WT animals was only observed at the time point of 24 hr post carrageenan injection [F(1,10)=4.878; p=0.05] (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia, allodynia, edema and increase in TNF-α paw levels in α5 KO and WT mice.

Differences in paw withdrawal latencies (Δ PWL=contralateral–ipsilateral hindpaw latencies) (A) and mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds (PWT) (B) in α5 KO and their WT littermate mice different times after intraplantar injection of carrageenan (0.5 % solution/20 μl). Degree of edema (C), as measured by the difference in the ipsilateral paw diameter before and after injection (ΔPD), in α5 KO and WT mice 6 hrs after intraplantar injection of carrageenan. Effect of carrageenan on TNF-α paw levels (D) at 6 hours after intraplantar injection of carrageenan in α5 KO and WT mice. Data were expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of 6 animals for each group. *p<0.05 significantly different from the value of saline treated WT group, #p<0.05, significantly different from the value of carrageenan treated WT group. BL: baseline.

We then measured paw TNF-α concentrations after intraplantar injection of 0.5% carrageenan. As shown in Fig 3D, TNF-α levels in the paw were significantly increased in α5-WT mice after carrageenan injection compared with vehicle treated WT mice [F(1,10)=22.58; p<0.001]. On the other hand, α5 KO mice showed significantly lower levels of TNF-α 6 hours after carrageenan injection compared with carrageenan-treated WT mice [F(1,10)=6.793; p<0.05] (Fig 3D).

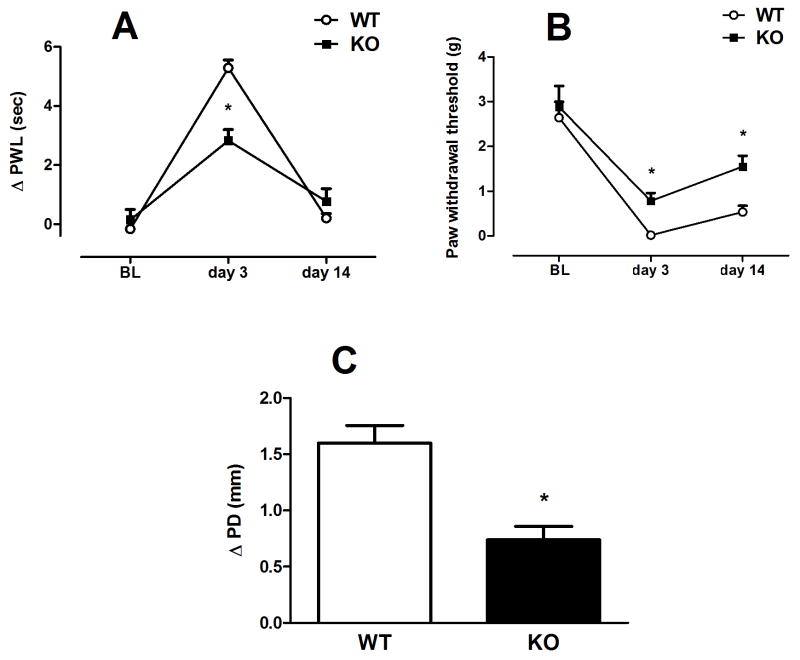

3.4. Hyperalgesia, Allodynia and Inflammation in α5 Knockout Mice in The CFA Test

Mice were given an intraplantar injection of CFA and then tested for hyperalgesia, allodynia and edema 3 and 14 days later. Prior to CFA injection, α5 KO and WT mice did not differ in heat and mechanical baselines (Fig. 4A & 4B). However our results indicated that there is significant difference between WT (n=6) and KO (n=8) animals in development of CFA-induced inflammation as observed by changes in heat latencies and paw edema [F(1,12)=19.876; p<0.001 on day 3 and t=4.458, df=12; p<0.001 respectively] (Fig 4A and C). α5-KO mice showed reduction in heat hypersensitivity response on day 3 only. Additionally, there is significant attenuation of mechanical allodynia formation in KO (n=5) CFA-treated mice [F(1,11)=18.672; p<0.01 at day 3 and F(1,11)=18.97; p<0.01 at day 14] when compared with WT mice (n=7) (Fig 4B) on both day 3 and 14.

Fig. 4. CFA-induced hyperalgesia, allodynia and edema in α5 KO and WT mice.

Differences in paw withdrawal latencies (Δ PWL=contralateral–ipsilateral hindpaw latencies) (A) and mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds (PWT) (B) in α5 KO and their WT littermate mice different times after intraplantar injection of CFA (75 and 50% solution/20 μl, respectively). Degree of edema (C), as measured by the difference in the ipsilateral paw diameter before and after injection of 75% CFA (ΔPD), in α5 KO and WT mice days after intraplantar injection of CFA. Data were expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of 5–8 animals for each group. *p<0.05 significantly different from WT group. BL: baseline

3.5. Hyperalgesia and Allodynia in α5 Knockout Mice in the CCI-Induced Neuropathic Pain Model

Prior to any surgical procedure, α5 KO and WT mice did not differ in heat and mechanical baselines (Fig. 5A & B). The development of neuropathic pain was compared in α5 WT and KO mice in the CCI model. Our results show that α5 KO mice displayed a significant attenuation of heat hypersensitivity compared with WT mice [F(1,18)=14.457; p<0.01 at 3 weeks post-surgery (Fig. 5A; n=10/each group). However, a significant decrease in mechanical allodynia was observed at the 1-week time point post-surgery [F(1,10)=46.116; p<0.01] (Fig. 5B; n=6/each group).

Fig. 5. Chrna5 (α5 nAChR) deficiency impairs thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia responses in the injured sciatic nerve CCI model of neuropathic pain.

Differences in paw withdrawal latencies (Δ PWL=contralateral–ipsilateral hindpaw latencies) (A) and paw withdrawal thresholds (PWT) (B) were determined in WT and α5 KO mice at weekly different time points after chronic constrictive nerve injury (CCI) operation. Data were given as the mean ± S.E.M. of 6–10 animals for each group. *p<0.05 significantly different from the value of WT group. BL: baseline

3.6. Relevance of α5 to anti-allodynic effects of nicotine in the CCI test

Nicotine itself exerts anti-allodynic effects after both inflammatory and neuropathic injuries [22]. We tested the ability of i.p., i.c.v., i.t. and i.pl. (−)-nicotine to reverse mechanical allodynia produced by CCI and CFA in WT and KO mice. Although potency and efficacy varied by route of administration, nicotine was significantly effective against allodynia in WT mice by all injection routes (Fig. 6 & 7). The anti-allodynic effect of systemic nicotine administration (0.9 mg/kg, i.p.) in α5 WT and KO mice was tested 7 weeks after CCI surgery. Nicotine induced significant anti-allodynic effect in WT mice in a time dependent manner [F(5,30)=32.921; p<0.001]. On the other hand, KO mice failed to show any significant anti-allodynic effect at any of the time points tested [F(5,30)=1.36; p=0.267] (Fig 6A; n=6/each group). There were significant differences between WT and KO groups interaction [t=8.055, df=10; p<0.001] (Fig 6B).

Fig. 6. Altered anti-allodynic efficacy of nicotine in Chrna5 (α5 nAChR) mutant mice.

Nicotine (0.9 mg/kg, i.p.) reversed already-developed mechanical allodynia produced by CCI (week 7 post surgery) in the α5 WT but not in KO mice. The mechanical paw withdrawal threshold of ipsilateral paw (A) and AUC of threshold values (B) are shown. Data were expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of 6 animals for each group. *p<0.05 significantly different from test 0. #p<0.05 significantly different from corresponding value of WT group. BL: baseline.

Fig. 7. Anti-allodynic effects of supraspinal, spinal and/or peripheral nicotine in α5 mutant mice.

A head-to head comparison of supraspinal (25 μg/5μl, i.c.v.) (A), spinal (20 μg/5μl, i.t) (B) and peripheral (45 μg/20 μl, intraplantar) (C) nicotine anti-allodynia against CCI-induced neuropathic pain in α5 WT and KO mice were tested using identical parameters at the peak of allodynia (14 days post-CCI). Data were expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of 6 animals for each group. *p<0.05 significantly different from test 0. #p<0.05 significantly different from corresponding value of WT group. BL: baseline.

We then performed a head to-head comparison of supraspinal, spinal and peripheral nicotine-induced anti-allodynia (25 μg, i.c.v.; 20 μg, i.t.; 45 μg, i.pl.) in α5 null mutant mice after neuropathic (CCI) injury (2 weeks after surgery). All routes of administration produced robust reversal of mechanical allodynia in WT mice at these doses (Fig. 7; n=6/each group). Supraspinal nicotine anti-allodynia was preserved in α5 KO mice [F(4,40)=13.16; p<0.001] (Fig. 7A). In contrast, spinal nicotine anti-allodynia was abolished in α5 KO mice [F(4,40)=0.5268; p=0.8609] (Fig. 7B). Similarly, anti-allodynia resulting from injection of nicotine directly into the hind paw was abolished in α5 KO mice [F(4,40)=2.313; p=0.0741] (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that nicotine blocks mechanical allodynia in the periphery and/or spinal cord in a α5-dependent manner, except supraspinally, where it appears to have minimal contribution.

3.7. Impact of α5 gene deletion on acetic acid-induced conditioned place aversion

Mice were given an i.p. injection of acetic acid (AA) (1.2%, n=8/WT and n=7/KO) or saline (n=6/each group) and then tested for place preference. In the CPA test, WT mice showed significant AA-induced aversion [t = 3.79, p < 0.05]. On the other hand, KO mice failed to show a significant aversive effect [t = 0.75, p = 0.469]. The α5-lacking mice showed reduction in aversive response [t = 3.404, p < 0.05] (Fig 8).

Fig. 8. Conditioned place aversion test in α5 KO and WT mice.

Intraperitoneal injection of 1.2% acetic acid induced conditioned place aversion as a negative affective component of pain. Data were given as the mean ± S.E.M. of 6–8 animals for each group. *p<0.05, compared to the vehicle-injected mice. #p<0.05, compared to the acetic acid-injected WT mice.

3.8. Impact of α5 gene deletion on motor activity and coordination of mice

To determine whether the effects of α5 gene deletion of mice in behavioral pain tests are not due to disruption of locomotor activity and coordination during testing, we evaluated motor activity and coordination of mice. As seen in Table 1, WT (n=10) and KO (n=8) mice in this study did not significantly differ in motor activity (t=0.03628, df=16; P = 0.9715) or motor coordination (t=1.398, df=10; P = 0.1923, n=6/each group) in any time-point after testing.

Table 1. Impact of alpha5 gene deletion on motor activity and coordination of mice.

Mice were placed into photocell activity cages for 30 min or placed on the rotarod for 5 min. Data were presented as mean ± SEM as the number of photocell interruptions and time to fall in sec for each group respectively (n=6–10).

| Group | Spontaneous Activity (# Interrupts/10 min) | Rotarod Activity (Time to fall in sec) |

|---|---|---|

| WT mice | 509 ± 30 | 179.6 ±0.4 |

| KO mice | 492 ± 25 | 181 ± 1.4 |

4. Discussion

Nicotine and nicotinic receptors have been explored for the past three decades as a strategy for pain control. These receptors are widely expressed throughout the central and peripheral nervous system as well as immune cells. Despite encouraging results with many α4β2* agonists in animal models of pain, human studies showed a narrow therapeutic window of these drugs. However, the lack of understanding of the composition of nicotinic receptor subtypes mediating analgesia has hampered the clinical use of nicotinic agonists. The present study investigates the role of α5 subunits in the development and modulation of pain behaviors in mice. The α5 subunit is an accessory subunit as it can only form functional receptors when co-expressed with a principal subunit (such as α3, or α4) and one complementary subunit (β2 or β4, e.g. as α4β2α5 or α3β4α5 receptors) [23]. Our results showed that genetic deletion of α5 nicotinic subunits reduced pain-like behaviors, thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia in tonic, inflammatory and neuropathic pain mouse models. The reduction of inflammation as measured by the degree of paw edema in the carrageenan inflammatory test was accompanied by a reduction of carrageenan-induced increase in TNF-α paw levels. Furthermore, we also show that the antinociceptive effects of nicotinic agonists vary in their dependency on α5 nicotinic subunits in these chronic pain models. Moreover, our results with α5 KO mice showed that nicotine induces anti-allodynic effects through spinal and peripheral mechanisms. Finally, mice with the α5-deletion showed reduction in aversive response to acetic acid i.p. injection in the CPA test. Taken together, our results suggest a direct link of nicotinic mechanisms in the development of inflammatory and pain mechanisms, which are at least partly dependent on the α5 nAChRs.

The α5 subunit is expressed in different pain pathways in peripheral and central nervous systems such as primary afferents in the spinal cord, postsynaptic autonomic and somatic motor neurons, in glial cells [24] and in locus coeruleus small cells [25,26]. Moreover, individual neurons can express multiple subtypes of nAChRs. nAChRs subtypes containing α5 (such as α4α5β2*) are expressed on both inhibitory and excitatory interneurons in the spinal dorsal horn [27], thalamus [11,28] and hindbrain [11]. In vitro studies have shown that the expression of the α5 subunit may act to modulate the amount of α3β4 nAChR function in the habenulopeduncular tract and in other tissues, which express α3β4α5 nAChR [29]. This distribution suggests the possible involvement of α5* nAChRs in peripheral and/or central pain behavior responses.

We first explored the involvement of α5* nAChRs in the mouse formalin test, which has been used as a model for inflammatory tonic pain. Thermal nociception and early phase response (phase I) in the formalin test are caused predominantly by direct activation of peripheral C-fibers, whereas the late response (phase II) in the formalin test involves functional changes in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (i.e., central sensitization) [30,31]. In this study, α5 KO and WT mice were tested in the formalin test at 2.5 % concentrations. Our results suggest that α5* nAChRs are minimally involved in the acute (nociceptive) pain of the first phase but contribute to a large extent to the inflammatory pain, spinal cord neuronal sensitization, or both, which occur during the second phase. Furthermore, we investigated the possible role of α5 subunits in the antinociceptive effects of nicotine and two nicotinic partial agonists (varenicline and sazetidine-A) in the formalin test. Our results showed that the nicotine and sazetidine anti-nociceptive effects were fully dependent on α5 subunits in both phases I and II of the formalin test. These results along with our recent report [16], suggest that the antinociceptive effects of nicotine and sazetidine-A in the formalin test appears to be mediated largely by α4α5β2*-nAChRs subtypes. In contrast, α5*-nAChRs subtypes do not mediate the effects of varenicline in the same test.

Carrageenan produces a short-term local inflammation involving both neurogenic and non-neurogenic mechanisms, in which several mediators are involved including cytokines and cyclooxygenase products [32,33]. Based on the present results, participation of α5*-nAChRs in carrageenan-evoked mechanical allodynia is limited. In contrast, carrageenan-evoked thermal hyperalgesia was greatly prevented in α5-KO animals. In addition, inflammation-induced paw edema and increase in paw TNF-α levels were also reduced. It is plausible that the attenuation of the increase of TNF-α may contribute to the mechanism by which α5*-nAChRs reduces carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Indeed, a α5-dependent mechanism regulating the synthesis or release of pro-inflammatory chemokines such as TNF-α through a NF-kB pathway could mediate the inflammatory response to carrageenan. In line with this suggestive mechanism, it is well reported that activation of α7 nAChRs engages this anti-inflammatory signaling [34]. The results from the present study suggest that α5*-nAChRs are tonically involved in the modulation of subacute inflammatory pain. Similarly, disruption of α5 nicotinic gene in the mouse resulted in the reduction of chronic inflammation as seen in CFA-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia. Taken together, our results showed that α5-null mice exhibited impaired development of hyperalgesia and allodynia after inflammatory injury, namely that elicited by carrageenan or CFA, suggesting the importance of α5*-nAChRs as a target for the treatment of both acute and chronic inflammatory pain. Interestingly, intraplantar injection of CFA in the mouse was recently reported to increase the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) levels of α3 and β4 mRNAs [35]. While changes in the levels of α5 mRNAs were not reported in this study, it is possible that peripheral α5-containing nAChRs in DRGs contribute to nicotine anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive actions, and that α5-containing nAChRs (possibly α3α5β4*) in the DRGs undergo plasticity during inflammation. Finally, our results with CFA and carrageenan seem to be in contrast with a study showing that α5 KO mice have significantly more severe experimental colitis than WT controls when treated with dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) [36]. One possible explanation for this discrepancy could be that α5-dependent mechanisms play a differential role in the nociceptive circuitry associated with the chronic inflammatory and visceral pain signals. It is also possible that changes in the genetic background of the α5 KO mice over generations may have played a role in this discrepancy (the number of backcrossing generations was not reported in that study).

We then used CCI of the right sciatic nerve as a model of neuropathic pain to characterize pain behaviors of α5 KO mice. Not surprisingly, α5 deficiency led to a decrease in thermal hyperalgesia and to a lesser degree tactile allodynia. The reduction in sensory pain responses in α5 KO mice are in line with a recent study that has shown a role for the α5 nAChR subunit on pain mechanisms in spinal nerve-ligated rats [15]. In this study, the ligation of spinal nerves L5 and L6 induced an up-regulation of the α5 nAChR subunit levels in the outer lamina of the spinal cord dorsal horn ipsilateral to ligation. In addition, knock down of the α5 subunit in spinal nerve-ligated rats moderately alleviated mechanical allodynia. Furthermore, α5 antisense treatment in these rats resulted in a decrease in pCREB immuno-reactive nuclei in the outer laminae and enhancement ACh-evoked excitatory amino acid release. Interestingly, peripheral nerve injury greatly upregulated transcripts for the α5 and β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits within the spinal cord dorsal horn [37]. In another study, spinal nerve ligation resulted in an increase of the expression of several nAChR subunits ipsilaterally, including α5 subunit [38]. Taken together, these results suggest that α5*-nAChRs play an important role in changes in spinal connectivity (i.e., central sensitization) induced by nerve injury in rodents.

The discrepancies observed between α5 KO and WT mice in the heat hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia changes of the CFA and CCI tests (Figures 4 and 5) were unexpected. Several explanations could account for these discrepancies, with one possibility being the fact that heat and pain are transmitted through the anterior spinothalamic tract of the spinal cord, while tactile sensation is transmitted through the dorsal column of the spinal cord. These two different pathways could account for different α5-nAChRs receptor expression based on the pain stimulus used. However, the expression of these nicotinic subunits in these different pathways is not known.

Since nicotine itself has been shown to exert anti-allodynic effects after neuropathic injuries [39], we tested the ability of systemic nicotine to reverse mechanical allodynia produced by CCI in α5 WT and KO mice. Intraperitoneal nicotine was significantly effective against allodynia in WT mice, but Chrna5 (nAChR α5 gene) KO mice displayed no significant nicotine-induced anti-allodynia in the CCI test. The anti-allodynic activity of nicotine in CCI-induced neuropathic pain seems to be mediated by α5 nicotinic receptors expressed in spinal and/or peripheral sites.

The changes in pain behaviors tests after α5 gene deletion of mice are not due to disruption in locomotor activity and coordination of the animals during testing since α5 KO mice did not show any significant changes in these measures when compared to WT mice.

Since the experience of pain has both sensory and emotional-affective dimensions, we evaluated the role of α5*-nAChR in aversion, an important affective component of pain, using a conditioned place aversion (CPA) test [40,41]. In the present study, acetic acid i.p. injection was paired to a compartment and induced an avoidance response in comparison to a saline-paired compartment, indicating that the acetic acid-produced aversion. Our results indicated also that there is a significant decrease in acetic acid -induced CPA in α5 KO compared to α5 WT animals. This result suggests that α5 nAChRs may play an important role in negative affective components of pain.

The mediation of nicotine’s anti-nociceptive effects in inflammatory and neuropathic pain by α5*-nAChRs extends previous results from our lab and others on the role of this modulatory subunit in nicotine pharmacological and behavioral effects. Indeed, an important role for α5 nicotinic subunit in the initial pharmacological effects of nicotine (antinociception in acute pain models) and nicotine reward and withdrawal was reported [10–13, 42,43].

To summarize, we have provided strong evidence that α5*-nAChRs seems to play an important role in the genesis of inflammatory and neuropathic pain sensitization and hypersensitivity. However, this conclusion does not exclude the possibility that our results may be impacted by compensatory mechanisms resulting from the genetic deletion of the α5 subunit. While α5 KO mice were reported with no visible abnormality or neurological deficits [9], normal brain anatomy, normal mRNA expression of other nAChR subunits, and normal nicotinic binding in the brain [10], it is possible that mutation of α5*-nAChRs in a complex circuitry involved in chronic pain may be compensated by changes in other elements in the circuitry.

Finally, our results may have an impact on the development of nicotinic ligands as possible therapeutic targets for chronic pain. Several high affinity α4β2* nAChR agonists were reported to have potent analgesic activity in rodent models of acute and chronic pain. However, much less is known about the exact composition of the native α4β2* receptor mediating the analgesic effect and their sites of action. Indeed, various additional nAChR subunits can associate with the α4 and β2 nicotinic subunits, including α5, α6, α7 and β3 subunits, to form multiple functional subtypes (for example α4α5β2* subtypes), which have been identified in the spinal cord and DRG tissues. Our current data demonstrate that, in both chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain models, nicotine blocks mechanical allodynia in a α5*-dependent manner. It is therefore possible that the modest efficacy of some α4β2* agonists reported in animal models of chronic inflammatory pain [31] and initial clinical studies [44–46]; may be related to their insufficient binding and/or functional activity at α5* subtypes. We believe that the refocusing of nicotinic analgesic development on α5*-containing receptors will lead to more efficacious compounds.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIDA DA-12610. Deniz Bagdas would like to thank The Scientific and Technical Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) for her postdoctoral research scholarship (2219-2013). The authors wish to thank Tie Han, Lisa Merritt and Cindy Evans for their technical assistance and maintenance of the breeding colony. The authors wish to thank Asti Jackson for her editing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- nAChRs

nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

- CCI

chronic constriction nerve injury

- PWL

paw withdrawal latency

- CFA

complete freund’s adjuvant

- KO

knock-out

- WT

wild-type

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- AUC

area under the curve

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest associated with this study to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gotti C, Clementi F, Fornari A, Gaimarri A, Guiducci S, Manfredi I, et al. Structural and functional diversity of native brain neuronal nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinemann S, Boulter J, Deneris E, Conolly J, Duvoisin R, Papke R, et al. The brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene family. Prog Brain Res. 1990;86:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincler MA, Eisenach JC. Immunocytochemical localization of the alpha3, alpha4, alpha5, alpha7, beta2, beta3 and beta4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in the locus coeruleus of the rat. Brain Res. 2003;974:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genzen JR, Van Cleve W, McGehee DS. Dorsal root ganglion neurons express multiple nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1773–1782. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Biasi M. Nicotinic receptor mutant mice in the study of autonomic function. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2002;1:331–336. doi: 10.2174/1568007023339148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerzanich V, Wang F, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom J. alpha 5 Subunit alters desensitization, pharmacology, Ca++ permeability and Ca++ modulation of human neuronal alpha 3 nicotinic receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:311–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramirez-Latorre J1, Yu CR, Qu X, Perin F, Karlin A, Role L. Functional contributions of alpha5 subunit to neuronal acetylcholine receptor channels. Nature. 1996;380:347–351. doi: 10.1038/380347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tapia L, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom J. Ca2+ permeability of the (alpha4)3(beta2)2 stoichiometry greatly exceeds that of (alpha4)2(beta2)3 human acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:769–776. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kedmi M, Beaudet AL, Orr-Urtreger A. Mice lacking neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor beta4-subunit and mice lacking both alpha5- and beta4-subunits are highly resistant to nicotine-induced seizures. Physiol Genomics. 2004;17:221–229. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00202.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salas R, Orr-Urtreger A, Broide RS, Beaudet A, Paylor R, De Biasi M. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha 5 mediates short-term effects of nicotine in vivo. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1059–1066. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson KJ, Marks MJ, Vann RE, Chen X, Gamage TF, Warner JA, et al. Role of alpha5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in pharmacological and behavioral effects of nicotine in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:137–146. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.165738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salas R, Sturm R, Boulter J, De Biasi M. Nicotinic receptors in the habenulo-interpeduncular system are necessary for nicotine withdrawal in mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3014–3018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4934-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler CD, Lu Q, Johnson PM, Marks MJ, Kenny PJ. Habenular α5 nicotinic receptor subunit signalling controls nicotine intake. Nature. 2011;471:591–601. doi: 10.1038/nature09797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang N, Orr-Urtreger A, Chapman J, Rabinowitz R, Nachman R, Korczyn AD. Autonomic function in mice lacking alpha5 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. J Physiol. 2002;542:347–354. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincler MA, Eisenach JC. Knock down of the alpha 5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in spinal nerve-ligated rats alleviates mechanical allodynia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;80:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AlSharari SD, Carroll FI, McIntosh JM, Damaj MI. The antinociceptive effects of nicotinic partial agonists varenicline and sazetidine-A in murine acute and tonic pain models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342:742–749. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.194506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon W. The up-and-down method for small samples. J Am Stat Assoc. 1965;60:967–78. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive for the quantitation of microgram quantitites of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedigo NW, Dewey WL, Harris LS. Determination and characterization of the antinociceptive activity of intraventricularly administered acetylcholine in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;193:845–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hylden JL, Wilcox GL. Intrathecal morphine in mice: a new technique. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;67:313–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vincler M. Neuronal nicotinic receptors as targets for novel analgesics. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2005;14:1191–1198. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.10.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown RW, Collins AC, Lindstrom JM, Whiteaker P. Nicotinic alpha5 subunit deletion locally reduces high-affinity agonist activation without altering nicotinic receptor numbers. J Neurochem. 2007;103:204–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan I, Osaka H, Stanislaus S, Calvo RM, Deerinck T, Yaksh TL, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor distribution in relation to spinal neurotransmission pathways. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:44–59. doi: 10.1002/cne.10913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Léna C, de Kerchove D’Exaerde A, Cordero-Erausquin M, Le Novère N, del Mar Arroyo-Jimenez M, Changeux JP. Diversity and distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the locus ceruleus neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12126–12131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincler M, Eisenach JC. Plasticity of spinal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors following spinal nerve ligation. Neurosci Res. 2004;48:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cordero-Erausquin M, Changeux JP. Tonic nicotinic modulation of serotoninergic transmission in the spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2803–2807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041600698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao D, Perry DC, Yasuda RP, Wolfe BB, Kellar KJ. The alpha4beta2alpha5 nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat brain is resistant to up-regulation by nicotine in vivo. J Neurochem. 2008;104:446–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.George AA, Lucero LM, Damaj MI, Lukas RJ, Chen X, Whiteaker P. Function of human α3β4α5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors is reduced by the α5(D398N) variant. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:25151–25162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.379339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coderre TJ, Melzack R. The contribution of excitatory amino acids to central sensitization and persistent nociception after formalin-induced tissue injury. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3665–3670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03665.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vissers K, Hoffmann V, Geenen F, Biermans R, Meert T. Is the second phase of the formalin test useful to predict activity in chronic constriction injury models? A pharmacological comparison in different species. Pain Pract. 2003;3:298–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-7085.2003.03033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doi Y, Minami T, Nishizawa M, Mabuchi T, Mori H, Ito S. Central nociceptive role of prostacyclin (IP) receptor induced by peripheral inflammation. Neuroreport. 2002;13:93–96. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200201210-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poole S, Cunha FQ, Selkirk S, Lorenzetti BB, Ferreira SH. Cytokine-mediated inflammatory hyperalgesia limited by interleukin-10. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:684–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14987.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pavlov VA, Wang H, Czura CJ, Friedman SG, Tracey KJ. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: a missing link in neuroimmunomodulation. Mol Med. 2003;9:125–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albers KM, Zhang XL, Diges CM, Schwartz ES, Yang CI, Davis BM, et al. Artemin growth factor increases nicotinic cholinergic receptor subunit expression and activity in nociceptive sensory neurons. Mol Pain. 2014;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orr-Urtreger A, Kedmi M, Rosner S, Karmeli F, Rachmilewitz D. Increased severity of experimental colitis in alpha 5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit-deficient mice. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1123–1127. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200507130-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang L, Zhang FX, Huang F, Lu YJ, Li GD, Bao L, Xiao HS, Zhang X. Peripheral nerve injury induces trans-synaptic modification of channels, receptors and signal pathways in rat dorsal spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:871–883. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2004.03121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young T, Wittenauer S, Parker R, Vincler M. Peripheral nerve injury alters spinal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor pharmacology. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;590:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vincler M. Neuronal nicotinic receptors as targets for novel analgesics. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2005;14:1191–1198. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.10.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LaBuda CJ, Fuchs PN. A behavioral test paradigm to measure the aversive quality of inflammatory and neuropathic pain in rats. Exp Neurol. 2000;163:490–494. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johansen JP, Fields HL, Manning BH. The affective component of pain in rodents: direct evidence for a contribution of the anterior cingulate cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8077–8082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141218998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson KJ, Martin BR, Changeux JP, Damaj MI. Differential role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in physical and affective nicotine withdrawal signs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:302–312. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jackson KJ, Sanjakdar SS, Muldoon PP, McIntosh JM, Damaj MI. The α3β4* nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtype mediates nicotine reward and physical nicotine withdrawal signs independently of the α5 subunit in the mouse. Neuropharmacology. 2013;70:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dutta S, Awni W. Population pharmacokinetics of ABT-594 in subjects with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37:475–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowbotham MC, Arslanian A, Nothaft W, Duan WR, Best AE, Pritchett Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of the α4β2 neuronal nicotinic receptor agonist ABT-894 in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2012;153:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowbotham MC, Duan WR, Thomas J, Nothaft W, Backonja MM. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of ABT-594 in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2009;146:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]