To the Editor:

Asthma exacerbations secondary to viral illnesses are an important cause of morbidity among children with asthma, and allergy is a risk factor for virus-induced exacerbations. Although less frequent, some exacerbations of asthma occur independently of viral illnesses. The patterns and cause of asthma exacerbations have been investigated in cross-sectional studies,1 but longitudinal data are lacking.

We sought to determine whether there are separate groups of children who have asthma exacerbations with viruses and children who have asthma exacerbations without viruses. In addition, we tested the hypothesis that there are distinct risk factors for virus-induced exacerbations and exacerbations not associated with viral infection.

The Childhood Origins of Asthma (COAST) study followed 259 children prospectively from birth to age 6 years, and 217 were followed until age 11 years. Of those, 102 children met the criteria for asthma at 6, 8, and/or 11 years of age (Table I ). This subset of COAST children was predominantly male (63%). Forty-nine percent had a family history of maternal asthma, and 34% had a history of paternal asthma. Forty-seven percent had aeroallergen sensitization at the age of 6 years and 52% at the age of 11 years. The majority (94%) lived in a home without smoke exposure. At year 6, 15% of children were taking a daily controller either seasonally or perennially compared with 35% of children by year 12.

Table I.

Factors associated with asthma exacerbations between ages 6 and 11 years in the COAST cohort (n = 102)

| No. | All exacerbations |

Viral exacerbations |

Nonviral exacerbations |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P value | Mean ± SD | P value | Mean ± SD | P value | ||

| Overall no. of exacerbations | 2.1 ± 3.3 | 1.3 ± 2.4 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 39 | 2.3 ± 3.9 | .61 | 1.4 ± 2.9 | .64 | 0.6 ± 1.4 | .91 |

| Male | 63 | 2.0 ± 2.9 | 1.2 ± 2.0 | 0.6 ± 1.0 | |||

| Year 6 aeroallergen sensitization | |||||||

| No | 35 | 1.7 ± 2.3 | .10 | 1.1 ± 1.8 | .27 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | .14 |

| Yes | 47 | 2.9 ± 4.1 | 1.8 ± 3.1 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | |||

| Year 11 aeroallergen sensitization | |||||||

| No | 23 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | .008 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | .03 | 0.4 ± 0.6 | .11 |

| Yes | 52 | 3.2 ± 4.1 | 1.9 ± 3.0 | 0.9 ± 1.5 | |||

| Maternal asthma | |||||||

| No | 53 | 1.7 ± 2.4 | .17 | 1.0 ± 1.8 | .21 | 0.5 ± 0.9 | .37 |

| Yes | 49 | 2.7 ± 4.0 | 1.6 ± 2.9 | 0.7 ± 1.4 | |||

| Paternal asthma | |||||||

| No | 66 | 2.0 ± 2.9 | .41 | 1.2 ± 2.1 | .65 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | .17 |

| Yes | 34 | 2.5 ± 4.0 | 1.5 ± 3.0 | 0.8 ± 1.5 | |||

| Smoke in home (year 6) | |||||||

| No | 94 | 2.2 ± 3.4 | .49 | 1.4 ± 2.5 | .16 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | .62 |

| Yes | 6 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | |||

| Dog in home (year 6) | |||||||

| No | 64 | 2.1 ± 3.2 | .79 | 1.3 ± 2.2 | .80 | 0.6 ± 1.3 | .69 |

| Yes | 36 | 2.3 ± 3.5 | 1.4 ± 2.9 | 0.7 ± 1.0 | |||

| Cat in home (year 6) | |||||||

| No | 75 | 2.5 ± 3.6 | .03 | 1.5 ± 2.7 | .11 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | .10 |

| Yes | 25 | 1.2 ± 1.9 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | |||

An asthma exacerbation was defined as an illness in which a child required a step-up plan of care, use of oral corticosteroids, or both. A severe asthma exacerbation was defined by the use of oral corticosteroids.

Nasal samples were collected during asthma exacerbations and analyzed for respiratory tract viruses. Respiratory tract viruses were identified by using multiplex PCR.2 Allergen-specific IgE levels were measured by using ImmunoCAP (Phadia, Portage, Mich) performed at age 6 and 11 years, and positive results were defined as 0.35 kU/L or greater.3

Of the 102 COAST children with asthma, 60% had at least 1 exacerbation between ages 6 and 11 years, and 38% had more than 1 exacerbation. When grouped by exacerbation cause, 40 (40%) children had no exacerbations, 23 (22%) had only viral exacerbations, 13 (13%) had only nonviral exacerbations, and 19 (19%) had a mixture of both viral and nonviral exacerbations. There were 7 (6%) children who each had 1 exacerbation but no nasal sample. Children who had only viral or only nonviral exacerbations had fewer exacerbations on average (mean, 2.4 [95% CI, 1.3-4.4] and 1.5 [95% CI, 0.6-3.4], respectively) than children who experienced both viral and nonviral exacerbations (mean, 6.9 [95% CI, 4.7-10.1]). Children with at least 2 exacerbations had the highest prevalence of allergic sensitization and total IgE levels at age 11 years (see Table E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

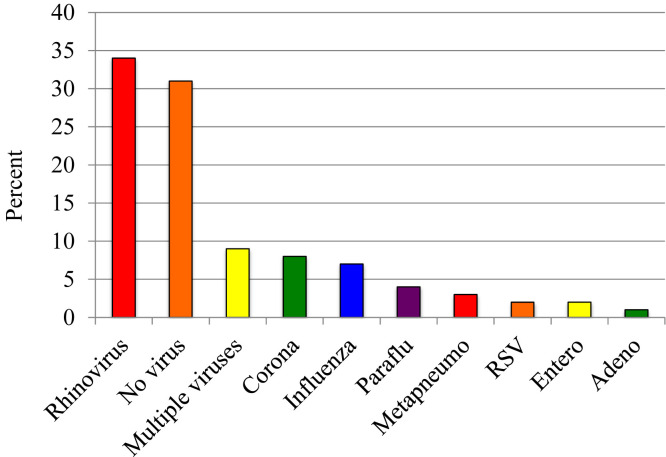

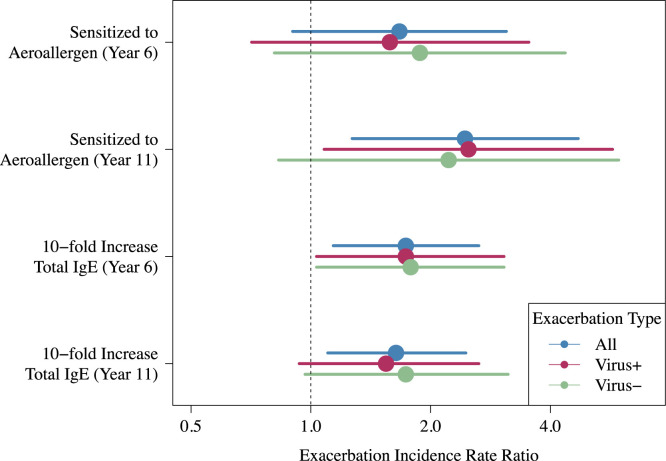

There were a total of 217 exacerbations, of which 192 included nasal samples obtained for viral analysis. Viruses were identified in 69% of exacerbations, and rhinovirus was most commonly identified (34% of exacerbations, see Fig E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). The total number of exacerbations was positively associated with total IgE levels at age 6 years (P = .009; incidence rate ratio (IRR) with respect to a 1-unit increase in log10 IgE, 1.74 [95% CI, 1.15-2.64]) and 11 years (P = .02; IRR, 1.64 [95% CI, 1.10-2.46]), and with aeroallergen sensitization at age 11 years (P = .008; IRR, 2.44 [95% CI, 1.27-4.70]; Fig 1 ). Having a cat in the home at year 6 was associated with a reduced number of exacerbations (IRR, 0.47 [95% CI, 0.24-0.91]; P = .03).

Fig E1.

Virology of exacerbations. RSV, Respiratory syncytial virus.

Fig 1.

Aeroallergen sensitization and higher total IgE levels were associated with greater numbers of exacerbations. Aeroallergen sensitization and total IgE levels are also associated with the number of both viral and nonviral exacerbations.

Risk factors for viral and nonviral exacerbations were similar. For example, viral exacerbations were positively associated with total IgE levels at age 6 years (P = .04; IRR, 1.76 [95% CI, 1.02-3.02]) and aeroallergen sensitization at age 11 years (P = .03; IRR, 2.49 [95% CI, 1.08 5.73]), and nonviral exacerbations were positively associated with total IgE levels at age 6 years (P = .04; IRR, 1.77 [95% CI, 1.02-3.08]) and aeroallergen sensitization at age 11 years (trend: P = .11; IRR, 2.22 [95% CI, 0.83-5.94]; Fig 1).

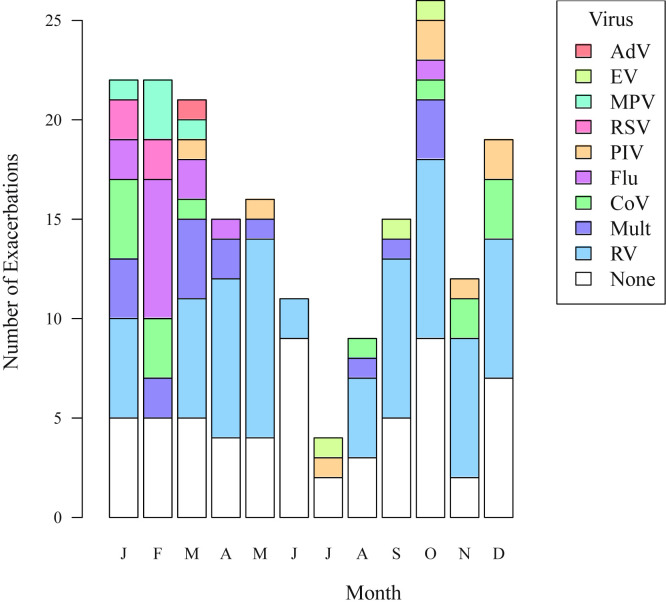

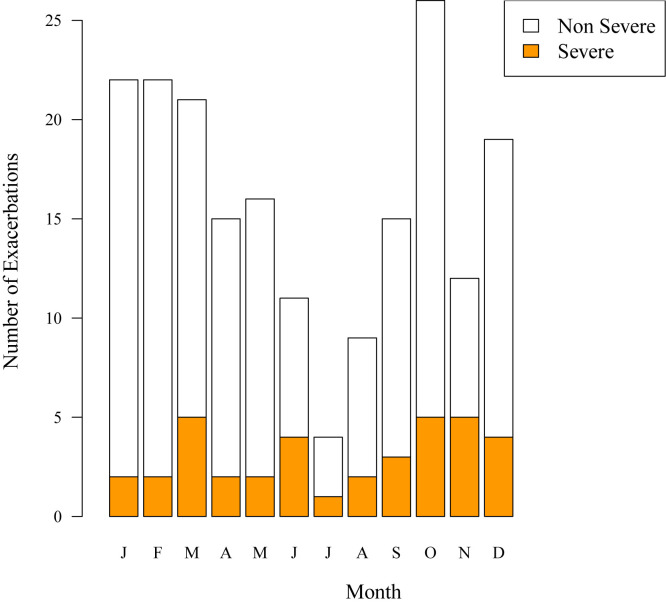

Finally, we compared the severity of viral versus nonviral exacerbations. Twenty-three percent (14/60) of nonviral exacerbations and 17% (23/132) of viral exacerbations were severe (P = .34). Of the 37 severe exacerbations, 14 (38%) were nonviral, 14 (38%) were associated with rhinovirus infection, and 9 (24%) were associated with other viruses. The greatest number of severe exacerbations, regardless of cause, occurred during the fall (October and November) and spring (March, see Figs E2 and E3 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

Fig E2.

Virology of exacerbations by month. AdV, Adenovirus; CoV, coronavirus; EV, enterovirus; MPV, metapneumovirus; Mult, multiple viruses; PIV, parainfluenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus.

Fig E3.

Severity of exacerbations by month.

This study provides new data about patterns of asthma exacerbation over a 6-year span in a cohort of suburban children. Notably, children who experienced multiple episodes had at least 1 viral exacerbation. Risk factors for having viral or nonviral asthma exacerbations were similar and consisted of indicators of atopy (ie, total IgE and aeroallergen sensitivity).

Previous studies have established that atopy is a risk factor for virus-induced wheezing and exacerbations of asthma. For example, wheezing illnesses in children older than 2 years are most common in children who have rhinovirus infections together with allergic sensitization, nasal eosinophilia, or increased nasal eosinophil cationic protein levels.4 Additional studies have identified increased expression of the FcεRI receptor on monocytes and dendritic cells during acute asthma exacerbations.5 One potential mechanism by which IgE could affect viral exacerbations relates to effects of the FcεRI on interferon responses. In vitro experiments demonstrated that increased FcεRI expression on plasmacytoid dendritic cells and IgE cross-linking strongly inhibited rhinovirus-induced interferon production in cells from children with allergic asthma.6

Strengths of the current study include the longitudinal analysis of exacerbations over a 6-year period. Much of the current literature evaluates the cause of asthma exacerbations from a cross-sectional perspective and not prospectively over multiple years. The study is limited by the relatively small numbers of children in each group, particularly the groups with only viral and only nonviral exacerbations, and the fact that most of the children with asthma in this cohort study have relatively mild disease.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that atopy is an important risk factor for both viral and nonviral exacerbations. These data are consistent with a clinical study of omalizumab, in which blocking IgE-mediated inflammation prevented both viral and nonviral exacerbations in children with moderate-to-severe asthma.7 One implication of these findings is that treatment aimed at reducing levels of IgE or perhaps other effectors of allergic inflammation could represent a common strategy to reduce morbidity caused by viral and nonviral asthma exacerbations.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant nos. P01 HL70831 and UL1TR000427).

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: D. J. Jackson has received research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and has received consultancy fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Genentech. R. E. Gangnon has received research support from the NHLBI. M. D. Evans has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). R. F. Lemanske, Jr, reports grants from the University of Wisconsin during the conduct of the study; other from board membership and personal fees from the University of Wisconsin; grants from the NHBLI; personal fees from Merck, Sepracor, SA Boney and Associates, GlaxoSmithKline, the American Institute of Research, Genentech, Double Helix Development, and Boehringer Ingelheim, Michigan Public Health, Allegheny General Hospital, the AAP, West Allegheny Health, California Chapter 4, the Colorado Allergy Society, the Pennsylvania Allergy Society, Howard Pilgrim Health, the California Society of Allergy, the NYC Allergy Society, the World Allergy Organization, APAPARI, Elsevier, UpToDate, the Kuwait Allergy Society, Lurie Children's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Health Star Communications, LA Children's Hospital, and Northwestern University, and the Western Society of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology outside the submitted work; and grants from Pharmaxis outside the submitted work. J. E. Gern has received research support from the NIH, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck and has received consultancy fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, and Genentech. A. T. Coleman declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Table E1.

Characteristics of children with 0, 1, or 2 or more exacerbations

| No. of exacerbations |

P value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | ≥2 | 0 vs ≥2 | 1 vs ≥2 | |

| No. of children | 40 | 23 | 39 | ||

| Sex | 17 F, 23 M | 7 F, 16 M | 15 F, 24 M | .71 | .52 |

| Maternal asthma | 50% | 39% | 51% | .91 | .35 |

| Paternal asthma | 33% | 36% | 33% | 1.00 | .81 |

| Maternal allergy | 90% | 83% | 84% | .44 | .87 |

| Paternal allergy | 84% | 75% | 86% | .78 | .30 |

| Aeroallergen sensitization (sIgE), year 6 (kU/L) | 60% | 41% | 63% | .81 | .14 |

| Aeroallergen sensitization (sIgE), year 11 (kU/L) | 74% | 44% | 78% | .73 | .02 |

| Total IgE, year 6 (kU/L) | 51 (25-126) | 46 (9-129) | 96 (25-280) | .62 | .09 |

| Total IgE, year 11 (kU/L) | 49 (26-460) | 59 (18-228) | 119 (44-472) | .53 | .04 |

| Positive skin test response, year 9 | 56% | 47% | 62% | .60 | .29 |

| Feno, year 6 (ppb) | 9.1 (7.2-11.1) | 5.9 (4.7-11.0) | 7.9 (6.1-18.3) | .74 | .14 |

| Feno, year 8 (ppb) | 8.1 (7.0-10.1) | 8.9 (5.2-20.0) | 10.6 (7.6-28.7) | .14 | .28 |

| Feno, year 11 (ppb) | 15.0 (9.4-24.5) | 10.6 (8.8-24.6) | 15.7 (8.7-32.4) | .76 | .61 |

| Blood eosinophils (%), year 6 | 3.0 (1.0-5.0) | 2.5 (1.0-4.0) | 3.0 (1.0-5.2) | .71 | .96 |

| Blood eosinophils (%), year 8 | 4.0 (2.0-5.0) | 2.5 (1.0-5.0) | 4.0 (2.5-5.5) | .45 | .04 |

| Blood eosinophils (%), year 11 | 5.0 (2.0-6.0) | 4.0 (1.0-5.2) | 4.0 (2.0-6.0) | .69 | .18 |

F, Female; Feno, fraction of exhaled nitric oxide; M, male; ppb, parts per billion.

References

- 1.Johnston S.L., Pattemore P.K., Sanderson G., Smith S., Lampe F., Josephs L., et al. Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9-11 year old children. BMJ. 1995;310:1225–1229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6989.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee W.M., Grindle K., Pappas T., Marshall D.J., Moser M.J., Beaty E.L., et al. High-throughput, sensitive, and accurate multiplex PCR-microsphere flow cytometry system for large-scale comprehensive detection of respiratory viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2626–2634. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02501-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson D.J., Gangnon R.E., Evans M.D., Roberg K.A., Anderson E.L., Pappas T.E., et al. Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:667–672. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rakes G.P., Arruda E., Ingram J.M., Hoover G.E., Zambrano J.C., Hayden F.G., et al. Rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus in wheezing children requiring emergency care. IgE and eosinophil analyses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:785–790. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9801052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt P.G., Strickland D.H., Sly P.D. Virus infection and allergy in the development of asthma: what is the connection? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:151–157. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283520166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durrani S.R., Montville D.J., Pratt A.S., Sahu S., DeVries M.K., Rajamanickam V., et al. Innate immune responses to rhinovirus are reduced by the high-affinity IgE receptor in allergic asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busse W.W., Morgan W.J., Gergen P.J., Mitchell H.E., Gern J.E., Liu A.H., et al. Randomized trial of omalizumab (anti-IgE) for asthma in inner-city children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]