Abstract

CTnDOT is a 65kbp integrative and conjugative element (ICE) that carries genes encoding both tetracycline and erythromycin resistances. The Excision operon of this element encodes Xis2c, Xis2d, and Exc proteins involved in the excision of CTnDOT from host chromosomes. These proteins are also required in the complex transcriptional regulation of the divergently transcribed transfer (tra) and mobilization (mob) operons of CTnDOT. Transcription of the tra operon is positively regulated by Xis2c and Xis2d, whereas, transcription of the mob operon is positively regulated by Xis2d and Exc. Xis2d is the only protein that is involved in the excision reaction, as well as the transcriptional regulation of both the mob and tra operons. This paper helps establish how Xis2d binds the DNA in the mob and tra region. Unlike other excisionase proteins, Xis2d binds a region of dyad symmetry. The binding site is located in the intergenic region between the mob and tra promoters, and once bound Xis2d induces a bend in the DNA. Xis2d binding to this region could be the preliminary step for the activation of both operons. Then the other proteins, like Exc, can interact with Xis2d and form higher order complexes.

Keywords: Conjugative transposon, Integrative and Conjugative Element, Recombination directionality factor

1.1 Introduction

Bacteroides spp. are prevalent members of the human gut microbiome (1). The predominance of these organisms in the gastrointestinal tract makes them an ideal reservoir for horizontal gene transfer, as many harbor integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) that carry antibiotic resistance genes. Bacteroides spp. may initiate genetic transfer of these elements to other members of the gut microbiome, or to bacteria that pass through the gastrointestinal tract (2). This leads to the potential for significant dissemination of antibiotic resistances to a variety of bacteria. One well characterized ICE is the 65kb CTnDOT, which carries both erythromycin and tetracycline resistance genes. CTnDOT and related elements are prevalent within the population. In the 1990s the tetQ gene carried by CTnDOT and related elements, was detected in about 80% of Bacteroides isolates collected from both individuals with a Bacteroides infection and healthy volunteers(3).

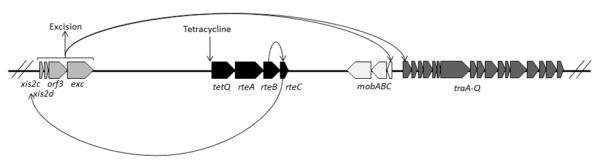

Normally, CTnDOT is found integrated within the host chromosome and is passively replicated when cellular chromosomal replication occurs. Under favorable conditions CTnDOT excises from the chromosome and forms a non-replicating double-stranded circular intermediate. Once this circle is nicked at the oriT site, a single stranded copy is transferred to the recipient cell via conjugation. Once inside the recipient cell, the single stranded copy is re-circularized and replicated before integration into the recipient chromosome (4-6). This transfer of CTnDOT DNA into a recipient cell is controlled by a highly complex regulatory cascade that is stimulated by tetracycline (Figure 1)(7).

Figure 1. Summary of CTnDOT regulatory cascade.

Upon exposure to tetracycline translation of the tetQ-rteA-rteB operon is stimulated. The RteB protein increases the transcription of rteC. RteC then acts upstream of the excision operon and increases transcription of that operon. The proteins in the excision operon are involved in excision of the CTnDOT element from the chromosome, as well as transcriptionally activating the divergently transcribed mob and tra operons. (1 column figure)

Transfer is initiated by tetracycline-induced expression of three regulatory proteins: TetQ, RteA, and RteB (8-10). TetQ is a tetracycline ribosomal protection protein, while RteA and RteB form a two component regulatory system. RteA functions as a sensor protein and RteB is a transcriptional activator of rteC expression (8). RteC in turn activates the expression of the excision operon containing the xis2c-xis2d-orf3-exc genes (11, 12). The first two genes in this operon, Xis2c and Xis2d, encode small, basic proteins with helix-turn-helix motifs that bind DNA. They have been shown to function as excisionases by binding attR DNA to promote CTnDOT excision (13). The function of orf3 is unknown, as no phenotype is observed when orf3 is deleted. Exc is a topoisomerase III, but the topoisomerase activity is not required for excision (14).

It is interesting to note that proteins expressed from the excision operon are not only involved in the excision reaction, they are also responsible for regulating transcription of the two divergently transcribed mobilization (mob) and transfer (tra) operons. Previous studies showed that Xis2c and Xis2d are involved in the transcriptional regulation of the tra operon, which consists of 17 genes (traA-traQ) encoding the mating apparatus of CTnDOT (15-17). Deletion of either orf3 or exc had no effect on the transcriptional regulation of the tra genes (16). Recent studies showed that Xis2d and Exc are responsible for positively regulating the transcription of the mob operon (18). The mob operon consists of three genes (mobA-mobB-mobC) that encode proteins in the relaxosome complex, which is responsible for transferring the CTnDOT DNA to the mating apparatus (18, 19). Deletions of either xis2c or orf3 have no effect on the transcriptional regulation of the mob genes (18).

The focus of this study is centered on Xis2d since it is involved in transcriptional activation of both the mob and tra operons. Prior to this study it was unclear where Xis2d interacts with DNA in the promoter region of these two operons to activate transcription. In this paper we show that Xis2d binds an area of dyad symmetry between the promoters of these two operons. Xis2d binding to this region is thought to be the initial step in the dual regulation of divergently transcribed operons, since Xis2d is required for the positive regulation of both operons. Then additional proteins, like Exc, may be recruited to form higher order complexes.

1.2 Materials and Methods

1.2.1 Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were grown aerobically in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C, and supplemented with ampicillin (100μg/ml) when appropriate.

Table 1.

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids

| Strain or Plasmid | Relevant Phenotype | Description and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5αMCR | RecA− | Strain for plasmid maintenance and purification. (GibcoBRL) |

|

BL21(DE3)

pLysS ihfA− |

Cmr | Novagen strain for overexpression of proteins with an ihfA gene deletion (J. Gardner, unpublished results) |

|

Rosetta(DE3)

pLysS ihfA− |

Cmr | Novagen strain for overexpression of proteins containing rare codons with an ihfA gene deletion (M.Wood, unpublished results). |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLYL72 | Ampr | Subclone of CTnDOT containing 18-kb transfer region, mobilization region, and oriT (34) |

| pGW40.5 | Ampr Cmr | Translation fusion of tra promoter to uidA reporter gene(15) |

| pPY190 | Ampr | Contains the immI region of phage P22 (35) |

| pBend2 | Ampr | Contains two unique coding sites flanked by direct repeats of polylinkers containing multiple restriction enzyme sites (36) |

| pBend138 | Ampr | Contains the 138bp tra fragment cloned into pBend1 (This study) |

| pET-27b(+) | Kanr | Plasmid for protein overexpression (Novagen) |

1.2.2 Gel Filtration

The low molecular weight calibration kit (GE) was used as described by the manufacturer with a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75pg column. The working concentration of Xis2d was 285uM.

1.2.3 Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

DNA substrates were amplified using primers listed in Table 2 and the resulting DNA products were purified by gel extraction as described by the manufacturer (Qiagen). Reactions were performed in 10μL volumes containing 2μL GSBA buffer [50mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1mM EDTA, 50mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.01 mg/ml heparin] and the substrate DNA. Reactions were then incubated with indicated concentrations of protein for 20 minutes before samples are loaded onto a 6% DNA retardation gel (Invitrogen) running at 100V/20mA.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| Tra and mob region: | |

| Out-tra-shift-F | CCGTCAGGGGACGGATTGGG |

| Tra-promoter-F | GGTATCGGACAGATGCTTGACCC |

| In-tra-shift-F | CGTGCTGCCACTTGCTTGGG |

| In-tra-shift-R | GGTGTGCTTTCAGTCCTTCATCC |

| Out-tra-shift-R | CCGGTCACGGCAGCGTATTG |

| Up-tra-R | GCTTTAAGGGCGTAACTTTGCC |

| Leader-region-F | GGATGAAGGACTGAAAGCACACC |

| Bend138-F | GCAATGTCTAGAGGTATCGGACAGATGCTTGACCC |

| Bend138-R | GCAATGGTCGACGGTGTGCTTTCAGTCCTTCATCC |

| Non-specific DNA: | |

| Anti-Omnt | GATCATCTCTAGCCATGC |

| Intra-arc | CCGCTACCTTGCGTACCAAATCC |

Gels were stained by shaking in 1X TBE-Sybergreen solution for 45 min and the DNA fragments were visualized using a transilluminator (Bio-Rad).

1.2.4 DNaseI fluorescent footprinting

A DNA substrate containing 235bp of the transfer operon promoter region was amplified with a set of primers, with one primer containing a 5′ 6-FAM label (Table 2). The reactions were conducted in 18μl volumes consisting of 1pmole DNA, 3mM CaCl2, 7mM MgCl2, 9.5% glycerol, 50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 250μg/ml BSA, and 2μL protein dilution buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 800mM KCl, 2mg/ml BSA). Reactions were incubated with indicated concentrations of protein for 30 minutes at room temperature. Then 2μL of DNaseI (0.125μg/ml) was added to each reaction and samples were allowed to digest for 1 minute. The reactions were stopped by adding 1 volume of 0.5 M EDTA and were cleaned up using a PCR cleanup kit (Qiagen) and eluted with 30μl EB buffer. Capillary electrophoresis was performed by the University of Illinois sequencing center and results were analyzed using GeneMapper software. Identities of the protected bases were determined by matching the GeneMapper results with a chromatogram produced using Thermo Sequenase Dye Primer manual cycle sequencing kit (USB corporation).

1.2.5 Protein Purification

The detailed procedures used in this study to purify Xis2d and Exc have been described previously (16, 20, 21). To summarize the Xis2d and Exc proteins were overexpressed on pET-27b(+) in BL21 (DE3) pLysS ihfA− and purified over a heparin-agarose column. The identity of the proteins was confirmed by mass spectrometry (Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center).

1.2.6 pBend Assay

The 138bp tra fragment was cloned between direct repeats of polylinkers containing multiple restriction enzyme sites on pBend2 using primers Bend138-F and Bend138-R. Insertion of the 138bp fragment in between the multiple restriction enzyme sites was confirmed by sequencing. DNA fragments made by single digestions of pBend138 with MluI, Nhe I, Spe I, EcoRV, SmaI, NruI, RsaI, and BamHI were the same size, but had different ends. DNA fragments were then used for EMSA analysis as described above.

1.3 Results

1.3.1 Xis2d is a Dimer

The amino acid sequence of Xis2d predicts that a monomer of Xis2d is 14052.2 Daltons. In order to determine whether Xis2d is a monomer or multimer we employed size exclusion chromatography. The results show that Xis2d has a non-denatured molecular weight of approximately 28kDa (Suppl. Figure S1), indicating that it is a dimer in solution.

1.3.2 Binding of Xis2d to DNA

A 681bp fragment of DNA, containing the region between the mobilization operon and the divergently transcribed transfer operon, was divided into six different segments (A-F) to determine what regions are bound by Xis2d (Figure 2a). Fragment A contains the leader region of the tra operon, the tra promoter, and part of the mob promoter. When Xis2d was mixed with fragment A, a slower migrating complex was observed indicating that Xis2d binds to this region (Figure 2b). Because transcriptional activators often bind upstream of the transcription initiation start site (TIS), fragment A was divided into two different fragments to separate the regions upstream and downstream of the tra TIS (fragments B and C, respectively). As expected, Xis2d was capable of binding the smaller upstream fragment C, but was unable to bind the downstream fragment B (Figure 2b). Additional DNA fragments containing more of the upstream tra TIS region were created to determine if Xis2d binds upstream DNA. Fragment D contains the tra promoter and the mob promoter, fragment E contains part of the mob promoter and the area immediately downstream from the mob promoter, and fragment F contains the mob leader region and an oriT of CTnDOT. Xis2d bound to fragment D, but not to fragments E and F (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Xis2d Binding.

(a) The upstream tra region was divided into six different fragments (A-F) to test for Xis2d binding capabilities. The transcription initiation start site for the tra operon is designated as +1 in this paper, with all mentioned positions in reference to this point. Arrows indicate the location of the promoters and the direction of transcription. A * indicates that binding was detected with the indicated fragment. (b) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) containing each DNA fragment being tested with (+) and without (−) the presence of Xis2d. The concentration of Xis2d was 400nM. (C) EMSA containing each DNA fragment being tested with (+) and without (−) the presence of the Empty vector control. (2 column figure)

Xis2d binding is only detectible when the area within fragment C is present, suggesting that Xis2d binds specifically to a region within this fragment. To further validate that Xis2d specifically binds the region between the tra and mob promoters within CTnDOT, a DNA fragment from the immI region of phage P22 was used to determine if Xis2d was capable of binding non-specific DNA under the conditions used. As seen in Figure 2b, no binding was detected. Thus we conclude that Xis2d binds DNA specifically to a site within fragment C.

Because partially purified protein preparations were used in this study, empty vector controls were tested for each DNA fragment. The empty vector substrate is the extract collected after cells containing the expression vector pET27b were subjected to the purification protocol used to purify Xis2d. This ensures that any of the E. coli proteins that elute from the column with Xis2d are not responsible for the observed results. As can be seen in Figure 2c, the addition of the empty vector preparations did not alter the migration of the different DNA substrates. This indicates that none of the E. coli proteins present in the preparation are binding the tested DNA fragments.

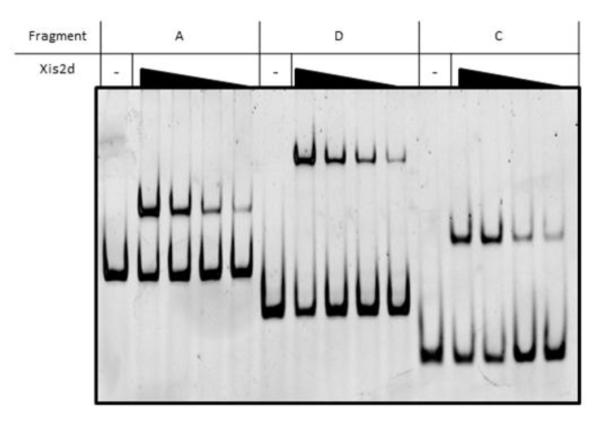

Of the DNA fragments tested, three (fragments A, C, D) were capable of binding Xis2d. The results in Figure 2 show experiments where Xis2d is present at only one concentration. Other excisionase proteins bind to multiple sites during the excision reaction. For example, when Lambda Xis and P22 Xis bind DNA several bands appear as the protein is diluted, representing different numbers of excisionase proteins bound to the DNA (22, 23). To determine whether Xis2d also binds to multiple sites we performed experiments using dilutions of Xis2d to determine if decreasing concentrations of the protein would reveal complexes of higher mobility. As seen in Figure 3, Xis2d shows a single shift when incubated with DNA, and that shift is observed as the protein is diluted. Since Xis2d shows a single band it suggests that either there is only a single Xis2d binding site in the mob and tra region, or multiple sites that bind Xis2d cooperatively.

Figure 3. Xis2d Binding Dilutions.

The three DNA fragments that interacted with Xis2d (Fragments A, C, and D) were tested with a range of Xis2d concentrations. The concentrations of Xis2d tested in this figure were 400nM, 150nM, 75nM, and 40nM. (1 column figure)

1.3.3 Footprinting of Xis2d

In order to identify the location of the base pairs bound by Xis2d between the mob and tra promoters, footprint analyses were performed. Fragment D was used for footprinting since it contains 97bp that Xis2d does not bind. This provides an internal control for analysis of the results, since the area within this region should not show a footprint. All DNA positions mentioned below are given relative to the tra TIS.

Protection in the presence of Xis2d was detected over a region of 45bp on the top strand from positions −87 to −42 (Figure 4). The bottom strand showed a similar footprint of 47bp with protection ranging from positions −94 to −47 (Suppl. Figure S2). This corresponds to the area between the mob and tra promoters. When Xis2d was diluted from 470nM to 80nM of protein, full protection was maintained until a dilution was reached (80nM) where the protein no longer protected any of the DNA (Figure 4). This 45bp area of protection may be bound by a single Xis2d dimer, which would explain why the entire protected region has the same affinity for Xis2d.

Figure 4. Xis2d Footprint.

DnaseI footprint of Xis2d on the top strand of the 235bp DNA fragment from position −96 to −30 relative to the tra TIS. The x-axis represents the length of the DNA fragment. The y-axis represents the florescent intensity, with the top of the scale set at 1000. The NP chromatogram is the no Xis2d control and the subsequent chromatograms show experiments performed with 470nM, 300nM, 150nM, and 80nM Xis2d. The dashed boxes highlight where footprints were observed, and the * symbol refers to peaks of enhanced cleavage. (2 column figure)

Peaks of enhancement are present on the footprint of both the bottom strand and the top strand. On the top strand there is a large peak of enhancement seen at −61 and two smaller peaks of enhancement seen at −51 and −71. On the bottom strand there are enhancement peaks at −55/56, −75, and −86. These peaks are located approximately 10bp apart, with the exception of the bottom strand where peaks −75 and −55/56 are separated by double that distance. When the lambda repressor binds to the operator sites the DNA forms loops that result in a similar enhanced cleavage pattern as seen in the footprint of Xis2d (24). It was proposed that DNA is wrapped around Tn916Xis when it showed a similar enhanced cleavage pattern, which suggests that the DNA between the transfer and mobilization operons may be wrapped around the Xis2d protein (25).

1.3.4 Scanning Mutagenesis

Some of the base pairs that are protected in the footprint assay may not interact specifically with Xis2d to mediate the binding. Some base pairs may be blocked from access by DNaseI, by interacting non-specifically with Xis2d, or by being wrapped around Xis2d. To identify base pairs that are required for Xis2d binding, systematic 9bp substitution mutations were made along the entire length of the area protected in the footprint assay. Nucleotides targeted for mutation were changed to the complementary base and the mutations made are shown in Figure 5a. Three different concentrations of Xis2d were used to determine the binding capabilities of each mutated fragment (Figure 5b, Suppl. Figure S3).

Figure 5. Scanning Mutagenesis.

(a) The 54bp region shown to be protected in the Xis2d footprint was sequentially mutated to the complement sequence to determine what regions of the fragment were important for binding. Underlined bases highlight the area that was mutated in each fragment. The percentage of DNA shifted for different concentrations of Xis2d (400nM and 100nM) is reported to the right of each fragment. (b) EMSAs of the DNA fragments being tested with 400nM and 100nM of Xis2d. The first lane of each EMSA is a DNA control and subsequent lanes correspond to each of the tested fragments. (2 column figure)

There was no effect on Xis2d binding when the regions from positions −95 to −72 (fragments 1-4) and −50 to −42 (fragment 11) were mutated. This suggests that the region between positions −72 and −50 interact with Xis2d. When the bases from positions −77 to −69 (fragment 5), −68 to −60 (fragment 7), and −55 to −47 (fragment 10) were mutated, Xis2d showed reduced binding affinity for the DNA substrate. When bases −59 to −51 (fragment 9) were mutated a minimal amount of binding was detectible, and no binding was detectible when bases from positions −73 to −65 (fragment 6), and −64 to −56 (fragment 8) were mutated.

The region where Xis2d binding was affected by mutation (−72 to −50) has a region of dyad symmetry from −51 to −66, which could be a Xis2d binding site. The regions shown to have no impact on binding when substitutions where made (positions −95 to −72, and −50 to −42) may be involved in non-specific interactions with Xis2d because they were protected from cleavage by DNaseI in the footprint experiments.

1.3.5 DNA Bending by Xis2d

The size of the footprint for Xis2d is large for a single dimer. However, if Xis2d binds DNA like IHF then bending of the DNA could increase the size of the footprint (26). The excisionase proteins of other systems, such as lambda Xis and P22 Xis, are known to bend the DNA they bind (22, 23).

Fragment C containing the tra promoter and half the mob promoter was cloned into pBend2 between direct repeats containing multiple restriction sites, as described in the Materials and Methods. The tandem multiple restriction sites move the position of the cloned DNA in relation to the ends of the DNA fragment, depending on which restriction enzyme is used. If Xis2d does not bend the DNA the migration of the fragments generated by the different restriction enzymes would be equivalent.

As seen in Figure 6 Xis2d bends the DNA which it binds. The slowest migrating complex was generated by SpeI, indicating that this complex contains Xis2d bound to the middle of the fragment (Figure 6). This places the center of the bend around positions −62 to −57. As summarized in Figure 7, this corresponds to the region in the Xis2d footprint where binding is lost when the DNA is mutated.

Figure 6. Xis2d Bending Assay.

EMSA of Xis2d binding bending substrates. Fragment D was cloned between direct repeats containing multiple restriction enzyme sites: MluI (1), NheI (2), SpeI (3), EcoRV (4), SmaI (5), NruI (6), RsaI (7), BamHI (8). Cutting with each of the restriction enzymes results in the Xis2d binding location shifting within the total fragment while retaining the fragment length. Lane “D” is unbound DNA. Xis2d concentration was 400nM. (1 column figure)

Figure 7. Summary of Xis2d Results.

The sequence from positions −204 to +31 relative to the tra transcription initiation site (+1) is shown. The transcription initiation start site (+1) is bold/italicized and all noted positions are in reference to this point. The double underline bases span the −7 and −33 boxes of the tra and mob promoters. The bases in bold type from positions −94 to −42 correspond to the bases that were protected in the footprinting assays when Xis2d was present. Of the protected bases those that are underlined correspond to areas where enhanced cutting was observed in the footprinting assays. The dashed box encircles areas where Xis2d binding was lost when the sequence was mutated and the solid line box indicates bases at the center of the bend induced by Xis2d binding. (2 column figure)

1.3.6 Xis2d and Exc Interaction

Both Xis2d and Exc are needed for the activation of the mob operon. Exc does not bind specifically to the DNA in the intergenic region of the mob and tra operons (Suppl. Figure S4). To determine if Exc interacts with Xis2d in this region an EMSA with both proteins was performed. Fragment D was incubated with 90nM Xis2d and increasing concentrations of Exc were added. As seen in Figure 8, a supershift was observed at higher concentrations of Exc (1.5 to 6.0uM). This indicates that Exc interacts with Xis2d. Since the topoisomerase function of Exc is not needed for the excision reaction it is possible that Exc serves more of a structural role, and that it interacts with Xis2d through protein-protein interactions(14).

Figure 8. Xis2d and Exc Binding.

Fragment D was incubated with Xis2d (0.09uM) and increasing concentrations of Exc. Lane “D” is DNA control. Lane “E” is the empty vector control. Lane 1 is Exc alone (6uM). Lane 2 is Xis2d alone (0.09uM). Lanes 3-8 have the same concentration of Xis2d (0.09uM), but have increasing concentrations of Exc added. Concentrations of Exc listed in the table above the EMSA. (1 column figure)

1.4 Discussion

Once the CTnDOT element excises from the chromosome, it is mobilized and transferred to a recipient cell. All three of these functions are needed for successful propagation of the element. Thus, it is understandable that the same protein (Xis2d) is involved in performing and regulating all of these processes. While previous studies examined the role of Xis2d in the excision reaction, less was known about the role of Xis2d in the expression of the tra and mob operons.

This paper establishes that the Xis2d protein binds specifically to the region upstream of the tra and mob promoters in CTnDOT. Because Xis2d is a dimer, the simplest model would be that it recognizes a sequence with dyad symmetry. By scanning the region that this study shows to be important for Xis2d binding, an area of dyad symmetry was revealed that resembled Xis2d binding sites in the attR region of CTnDOT (Figure 9). In addition to the similarity to attR binding sites, the center of the bend induced by Xis2d binding is in the middle of this dyad symmetry. Therefore, the dyad symmetry in the tra and mob intergenic region was designated XD. Upon closer inspection the attR D1 and D2 sites also exhibit partial dyad symmetry, but the right sides of the dyads show weak conservation. Alignment of XD to the D1 and D2 sites of attR shows a consensus of GGCRNN(A/W)C (Figure 10).

Figure 9. Xis2d Binds Dyad Symmetry.

The dyad symmetry (XD) found in the intergenic region between the tra and mob operons compared to the Xis2d sites in the attR region (D1 and D2). The sequence shown for XD is from position −78 to −46. The underlined bases in the XD sequence comprise the dyad symmetry and the arrows designate the direction of the symmetry. (1 column figure)

Figure 10. Xis2d Consensus Sequence.

Alignment of the left (XD-L) and right (XD-R) halves of the XD dyad symmetry and the D1 (D1-L and D1-R) and D2 (D2-L and D2-R) sites of attR. A summary of the number of times of each nucleotide appears at a given position is shown below the sites. A consensus sequence is shown at the bottom. (1 column figure)

In earlier work it was shown that mutations in the DNA upstream of the tra promoter affected transcription of the transfer genes. Mutating the DNA to the complement from positions −72 to −66 or −64 to −58 abolished detectible transcription of a traA::uidA fusion when CTnERL, a closely related element to CTnDOT, was provided in trans (16). That previous work did not determine which of the excision proteins bound to the regions containing these mutations. From work done in this study, it is clear that both of these mutations eliminate the left half of the XD dyad symmetry (Figure 9). In the previous study Xis2d was still able to bind mutations made from −72 to −66 and −64 to −58, so Xis2d was able to bind by recognizing the right half of the XD symmetry. However, without the intact XD site Xis2d is unable to make the appropriate contacts to activate tra transcription.

The binding pattern of Xis2d is different from other members of the excisionase family. Tn916Xis binds to three different sites, each one containing a 5′ AT rich region and a 3′ conserved binding sequence (25). Two of these sites are located on attL and are involved in promoting excision, while the other is located on attR and prevents excision at high Tn916Xis concentrations (27, 28). It has been proposed that Tn916Xis binds the sites cooperatively at high concentrations of protein (25). The P22, L5, and Pukovnik Xis proteins bind a series of four direct repeats in what appears to be a head to tail arrangement (23, 29, 30). Of these three Xis proteins, the Pukovnik Xis has been shown to form a filament (29). Since L5 and P22 Xis are similar to Pukovnik Xis it is possible that they also form a similar filament. The P2 cox protein has several binding sites in a variety of arrangements depending on the target DNA and it has also been shown to form filaments (31). In the Lambda attR site, a filament is formed by two Xis proteins binding specifically to a set of direct repeats, with another Xis binding non-specifically between the others (22). There are no crystal structures for any of the proteins involved in CTnDOT integration or excision. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that Xis2d is forming filaments that bind to DNA.

Xis2d is unusual because it participates in the excision reaction and is also involved in transcriptional activation of the mob and tra operons. No other ICE excisionases have been shown to have a similar dual functionality. However, the phage P2 cox protein is functionally similar to Xis2d. The cox protein is an excisionase that serves as a repressor of the Pc promoter on the P2 element, and also as an activator of the PLL promoter on the phage P4 (31-33). It has not been determined whether Xis2d is also able to regulate the promoters of unrelated elements.

Other known ICEs use a single excisionase protein. CTnDOT is unique since it contains an entire excision operon that encodes proteins that serve multiple functions. Xis2d is involved in multiple aspects of CTnDOT regulation and the other proteins of the excision operon appear to work with Xis2d to form elaborate multifunctional complexes. For example, while Exc does not appear to bind DNA in a sequence specific manner, it does appear to interact with Xis2d to form a complex that stimulates the transcription of the mob operon. To activate tra operon transcription both Xis2c and Xis2d are needed. Unfortunately Xis2c is unstable in our hands, but the strong structural similarity to Xis2d suggests that it binds DNA in a similar manner. Xis2c and Xis2d may form a complex that activates tra operon transcription.

Gaining an understanding of how Xis2d contributes to the regulation of these CTnDOT promoters is a preliminary step in unlocking the complexity of this system. Since the promoters of the mob and tra operons are separated by only 66bp and Xis2d is needed for the transcriptional regulation of both operons, it is possible that the initial step in the activation of Ptra and Pmob is the binding of Xis2d to the XD site. Then other required proteins can be recruited to drive transcription in either direction for the activation of the mob and tra operons.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Xis2d is the first excisionase from an ICE that has been characterized as a transcriptional regulator

Xis2d specifically binds a region of dyad symmetry

Xis2d induces bends in the DNA

Xis2d and Exc interact to form higher order complexes

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Margaret Wood for technical instruction and assistance. We would also like to thank Carolyn Keeton for helpful comments and discussion. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, grants AI 22383 and GM 28717.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

1.6 References

- 1.Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2009;326:1694–1697. doi: 10.1126/science.1177486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salyers AA, Gupta A, Wang Y. Human intestinal bacteria as reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes. Trends in microbiology. 2004;12:412–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoemaker NB, Vlamakis H, Hayes K, Salyers AA. Evidence for extensive resistance gene transfer among Bacteroides spp. and among Bacteroides and other genera in the human colon. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2001;67:561–568. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.561-568.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salyers AA, Shoemaker NB, Li LY. In the driver’s seat: the Bacteroides conjugative transposons and the elements they mobilize. Journal of bacteriology. 1995;177:5727–5731. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5727-5731.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salyers AA, Shoemaker NB, Stevens AM, Li LY. Conjugative transposons: an unusual and diverse set of integrated gene transfer elements. Microbiological reviews. 1995;59:579–590. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.579-590.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whittle G, Salyers AA. Modern Microbial Genetics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2002. Bacterial Transposons—An Increasingly Diverse Group of Elements; pp. 385–427. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters JL, Salyers AA. Regulation of CTnDOT conjugative transfer is a complex and highly coordinated series of events. mBio. 2013;4:e00569–00513. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00569-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens AM, Shoemaker NB, Li LY, Salyers AA. Tetracycline regulation of genes on Bacteroides conjugative transposons. Journal of bacteriology. 1993;175:6134–6141. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6134-6141.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Rotman ER, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA. Translational control of tetracycline resistance and conjugation in the Bacteroides conjugative transposon CTnDOT. Journal of bacteriology. 2005;187:2673–2680. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.8.2673-2680.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA. Regulation of a Bacteroides operon that controls excision and transfer of the conjugative transposon CTnDOT. Journal of bacteriology. 2004;186:2548–2557. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2548-2557.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moon K, Shoemaker NB, Gardner JF, Salyers AA. Regulation of excision genes of the Bacteroides conjugative transposon CTnDOT. Journal of bacteriology. 2005;187:5732–5741. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5732-5741.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park J, Salyers AA. Characterization of the Bacteroides CTnDOT regulatory protein RteC. Journal of bacteriology. 2011;193:91–97. doi: 10.1128/JB.01015-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keeton CM, Hopp CM, Yoneji S, Gardner JF. Interactions of the excision proteins of CTnDOT in the attR intasome. Plasmid. 2013;70:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutanto Y, Shoemaker NB, Gardner JF, Salyers AA. Characterization of Exc, a novel protein required for the excision of Bacteroides conjugative transposon. Molecular microbiology. 2002;46:1239–1246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeters RT, Wang GR, Moon K, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA. Tetracycline-associated transcriptional regulation of transfer genes of the Bacteroides conjugative transposon CTnDOT. Journal of bacteriology. 2009;191:6374–6382. doi: 10.1128/JB.00739-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeton CM, Park J, Wang G-R, Hopp CM, Shoemaker NB, Gardner JF, Salyers AA. The excision proteins of CTnDOT positively regulate the transfer operon. Plasmid. 2013;69:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittle G, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA. Characterization of genes involved in modulation of conjugal transfer of the Bacteroides conjugative transposon CTnDOT. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:3839–3847. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.14.3839-3847.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waters JL, Wang GR, Salyers AA. Tetracycline-related transcriptional regulation of the CTnDOT mobilization region. Journal of bacteriology. 2013;195:5431–5438. doi: 10.1128/JB.00691-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peed L, Parker AC, Smith CJ. Genetic and functional analyses of the mob operon on conjugative transposon CTn341 from Bacteroides spp. Journal of bacteriology. 2010;192:4643–4650. doi: 10.1128/JB.00317-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keeton CM, Gardner JF. Roles of Exc protein and DNA homology in the CTnDOT excision reaction. Journal of bacteriology. 2012;194:3368–3376. doi: 10.1128/JB.00359-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dichiara J. Dissertation. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign; Urbana, Illinois: 2006. DNA-Protein Interactions in the CTnDOT Excisive Intasome. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbani MA, Papagiannis CV, Sam MD, Cascio D, Johnson RC, Clubb RT. Structure of the cooperative Xis-DNA complex reveals a micronucleoprotein filament that regulates phage lambda intasome assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:2109–2114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607820104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattis AN, Gumport RI, Gardner JF. Purification and characterization of bacteriophage P22 Xis protein. Journal of bacteriology. 2008;190:5781–5796. doi: 10.1128/JB.00170-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hochschild A, Ptashne M. Cooperative binding of λ repressors to sites separated by integral turns of the DNA helix. Cell. 1986;44:681–687. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbani M, Iwahara M, Clubb RT. The structure of the excisionase (Xis) protein from conjugative transposon Tn916 provides insights into the regulation of heterobivalent tyrosine recombinases. Journal of molecular biology. 2005;347:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rice PA, Yang S, Mizuuchi K, Nash HA. Crystal structure of an IHF-DNA complex: a protein-induced DNA U-turn. Cell. 1996;87:1295–1306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connolly KM, Iwahara M, Clubb RT. Xis protein binding to the left arm stimulates excision of conjugative transposon Tn916. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:2088–2099. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.8.2088-2099.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinerfeld D, Churchward G. Xis protein of the conjugative transposon Tn916 plays dual opposing roles in transposon excision. Molecular microbiology. 2001;41:1459–1467. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh S, Plaks JG, Homa NJ, Amrich CG, Heroux A, Hatfull GF, VanDemark AP. The structure of Xis reveals the basis for filament formation and insight into DNA bending within a mycobacteriophage intasome. Journal of molecular biology. 2014;426:412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis JA, Hatfull GF. Control of directionality in L5 integrase-mediated site-specific recombination. Journal of molecular biology. 2003;326:805–821. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01475-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berntsson RP, Odegrip R, Sehlen W, Skaar K, Svensson LM, Massad T, Hogbom M, Haggard-Ljungquist E, Stenmark P. Structural insight into DNA binding and oligomerization of the multifunctional Cox protein of bacteriophage P2. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:2725–2735. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berntsson RP, Odegrip R, Sehlen W, Skaar K, Svensson LM, Massad T, Hogbom M, Haggard-Ljungquist E, Stenmark P. Structural insight into DNA binding and oligomerization of the multifunctional Cox protein of bacteriophage P2. Nucleic acids research. 2013 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis JA, Hatfull GF. Control of directionality in integrase-mediated recombination: examination of recombination directionality factors (RDFs) including Xis and Cox proteins. Nucleic acids research. 2001;29:2205–2216. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.11.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li LY, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA. Location and characteristics of the transfer region of a Bacteroides conjugative transposon and regulation of transfer genes. Journal of bacteriology. 1995;177:4992–4999. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4992-4999.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maloy SR, Gardner J. Dissecting nucleic acid-protein interactions using challenge phage. Methods in enzymology. 2007;421:227–249. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)21018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J, Zwieb C, Wu C, Adhya S. Bending of DNA by gene-regulatory proteins: construction and use of a DNA bending vector. Gene. 1989;85:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.