Abstract

Diet can impact sensitivity of rats to some of the behavioral effects of drugs acting on dopamine systems. The current study tested whether continuous access to sucrose is necessary to increase yawning induced by the dopamine receptor agonist quinpirole, or if intermittent access is sufficient. These studies also tested whether sensitivity to quinpirole-induced yawning increases in rats drinking the non-caloric sweetener saccharin. Dose-response curves (0.0032–0.32 mg/kg) for quinpirole-induced yawning were determined once weekly in rats with free access to standard chow and either continuous access to water, 10% sucrose solution, or 0.1% saccharin solution, or intermittent access to sucrose or saccharin (i.e., 2 days per week with access to water on other days). Cumulative doses of quinpirole increased then decreased yawning, resulting in an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve. Continuous or intermittent access to sucrose enhanced sensitivity to quinpirole-induced yawning. Continuous, but not intermittent, access to saccharin also enhanced sensitivity to quinpirole-induced yawning. In all groups, pretreatment with the selective D3 receptor antagonist PG 01037 shifted the ascending limb of the quinpirole dose-response curve to the right, while pretreatment with the selective D2 receptor antagonist L-741626 shifted the descending limb to the right. These results suggest that even intermittent consumption of diets containing highly palatable substances (e.g. sucrose) alters sensitivity to drugs acting on dopamine systems in a manner that could be important in vulnerability to abuse drugs.

Keywords: rat, yawning, dopamine receptor, fat, sucrose, saccharin, intermittent access, quinpirole

1. Introduction

Diet (e.g., type and amount of food consumed) can impact sensitivity to drugs acting on dopamine systems (Avena and Hoebel, 2003; Collins et al., 2008; Gosnell, 2005; Baladi et al., 2012a; Baladi et al., 2011a; Puhl et al., 2011). For example, rats eating a high fat chow or drinking a 10% sucrose solution are more sensitive than rats eating standard chow and drinking water to the behavioral effects of direct- (i.e., quinpirole; Baladi et al., 2011a,b) and indirect-acting (i.e., cocaine; Baladi et al., 2012b) dopamine receptor agonists. Although consumption of foods high in fat or sugar contributes to the development of obesity, sensitivity changes to the behavioral effects of drugs acting on dopamine systems even in the absence of weight gain (Baladi et al., 2011a,b); specifically, consuming a high fat or high sugar diet can markedly affect drug sensitivity in the absence of accelerated body weight gain.

Rats drinking sucrose are more sensitive than rats drinking water to the behavioral effects of quinpirole (Baladi et al., 2011b). Like many other direct-acting dopamine receptor agonists, quinpirole dose-dependently increases then decreases yawning in rats (Collins et al., 2008; Baladi and France, 2010) resulting in an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve. Experiments using selective dopamine receptor antagonists have revealed that the ascending limb (initiation of yawning) is mediated by dopamine D3 receptors, while the descending limb (inhibition of yawning) is mediated by dopamine D2 receptors (Collins et al., 2008; Baladi et al., 2011a; though see Depoortere et al., 2009; Sanna et al., 2011, 2012). The D3 receptor-mediated ascending limb of the quinpirole dose-response curve is shifted to the left in rats drinking sucrose (Baladi et al., 2011b). When consumption of highly preferred substances (fat or sugar) is restricted or access is intermittent, animals often increase consumption which is accompanied by an enhanced sensitivity to drugs acting indirectly on dopamine systems (Avena and Hoebel, 2003; Gosnell, 2005; Puhl et al., 2011). However, intermittency of access varied markedly across these studies and it is not known whether intermittent access to sucrose enhances sensitivity of rats to the behavioral effects of the direct-acting dopamine receptor agonist quinpirole.

While the mechanism(s) underlying these changes in sensitivity is not known, consumption of a diet high in sucrose or fat also causes metabolic changes (e.g., insulin resistance) that could impact drug sensitivity. Changes in insulin signaling can impact dopamine neurotransmission (Daws et al., 2011); however, non-caloric sweeteners such as saccharin are also highly preferred (compared with water) by rats (Carroll et al., 2007, 2008) but do not cause insulin resistance. Animals that show the greatest preference for sweeteners often are also more sensitive to drugs acting on dopamine systems (Carroll et al., 2008). The current study examined the effects of continuous or intermittent access to sucrose or saccharin solutions on sensitivity of rats to quinpirole-induced yawning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Male Sprague Dawley rats (N = 52; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA), weighing 250–300 g upon arrival, were housed individually in an environmentally controlled room (24±1°C, 50±10% relative humidity) under a 12:12 hr light/dark cycle (light period 0700–1900 hr). All rats had free access to food and water in the home cage except as indicated below. Animals were maintained and experiments were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and with the 2011 Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Sciences, the National Research Council, and the National Academy of Sciences).

2.2. Drinking Conditions

All 52 rats had free access to water in the home cage during the first week of the study when they were habituated to the facility and experimental procedures. The experiment was conducted at two different times in two separate cohorts. For cohort 1, beginning in week 2 and continuing for 16 weeks, 5 rats continued to have free access to water in the home cage, 5 had free access to a 10% sucrose in water solution, 5 had free access to a 0.1% saccharin solution, and two other groups of 5 rats each had free access to water 5 days per week and free access to sucrose or saccharin, respectively, for 2 days per week (intermittent access). Cohort 1 was tested with quinpirole once per week through week 12, and again in week 16. For cohort 2, beginning in week 2 and continuing for 16 weeks, 6 rats continued to have free access to water in the home cage, 6 had free access to 10% sucrose in water solution, 5 had access to a 0.1% saccharin solution, and two other groups of 5 rats each had free access to water 5 days per week and access to sucrose or saccharin, respectively, for 2 days per week. Cohort 2 was tested with quinpirole once per week through week 4, from weeks 8–12, and in week 16. Body weight, food and fluid intake were measured and recorded daily.

2.3. Yawning

Yawning was defined as an opening and closing of the mouth (~1 s) such that the lower incisors were completely visible (Baladi and France, 2010). On the day of testing, rats were transferred to test cages and allowed to habituate for 15 min. Yawning experiments were conducted at the same time each day (1400 hr). Yawning was assessed after injection of vehicle followed by injection of increasing doses of quinpirole (0.0032–0.32 mg/kg, i.p.) administered every 30 min using a cumulative dosing procedure. Beginning 20 min after each injection, the total number of yawns observed for 10 min was recorded (resulting in 6 observation periods per test). The dopamine D2 receptor selective antagonist L-741,626 (1.0 mg/kg) and the dopamine D3 receptor selective antagonist PG 01037 (56.0 mg/kg) were assessed for their ability to alter quinpirole-induced yawning. Antagonists were administered immediately after saline.

2.4. Body Temperature

Body temperature was measured in a temperature controlled room (24±1°C and 50±10% relative humidity) by inserting a lubricated thermal probe attached to a thermometer 3 cm into the rectum. Animals were adapted to the procedure by measuring body temperature on multiple occasions before assignment to an experimental condition. During yawning experiments, body temperature was measured upon completion of each 10-min yawning observation period and prior to the next injection. The dopamine D2 receptor selective antagonist L-741,626 (1.0 mg/kg) and the dopamine D3 receptor selective antagonist PG 01037 (56.0 mg/kg) were assessed for their ability to alter quinpirole-induced hypothermia.

2.5. Data Analyses

Quinpirole-induced yawning results are expressed as the average (± S.E.M.) number of yawns during each 10-min observation period plotted as a function of dose. With increasing cumulative doses, quinpirole increased then decreased yawning resulting in an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve (see results). The ascending and descending limbs of the dose-response curve were analyzed separately as follows: 1) by expressing each dose-response curve in an individual rat as a percentage of the maximal effect observed in that individual; 2) by determining the linear portion of the ascending and descending limbs of the curve, which included doses that spanned the 50% level of effect and included not more than one dose producing greater than 75% effect and not more than one dose producing less than 25% effect; and 3) by using linear regression to estimate the log ED50 for the ascending and the descending limb of each individual dose-response curve. Differences in log ED50 values and in maximal effects were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVAs with Geisser Greenhouse adjustment and Dunnett’s post hoc analyses with corrections for multiple comparisons by means of Graph Pad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, California, USA) and NCSS Statistical Software (NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, Utah, USA). Similar ANOVAs and post hoc analyses were used to examine differences in body temperature, body weight, and in food and fluid consumption. Results are shown and analyzed for both cohorts of rats (combined) except during weeks 5–7 in which only one cohort was tested with quinpirole.

2.6. Drugs

Quinpirole dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline and administered i.p. in a volume of 1 ml/kg body weight. L-741,626 (Tocris, Ellisville, Missouri, USA) was dissolved in 5% ethanol with 1 M HCl, added by drops until the solution was clear, and injected s.c., typically in a volume of 1 ml/kg body weight (see Baladi et al., 2011a; Collins et al., 2005, 2007). PG 01037 hydrochloride, generously provided by Dr. Amy Newman, was synthesized by J Cao in the Medicinal Chemistry Section, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse (Baltimore, Maryland, USA) using previously published methods (Grundt et al., 2005); PG 01037 was dissolved in 0.9% saline and administered s.c., typically in a volume of 1 ml/kg body weight.

3. Results

3.1. Body Weight

At the beginning of the experiment, when all rats were drinking water, the average (mean ± S.E.M.) body weight was 362.3 ± 2.9 g. Tests with quinpirole were conducted once per week for 2 weeks when all rats continued to drink water. During this time, all rats gained weight with the average body weight increasing to 372.1 ± 2.8 g. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA (feeding condition × day in study) revealed a significant main effect of feeding condition and a main effect of day (P < 0.05) but no significant interaction. By the end of the experiment, rats drinking water weighed 459.8 ± 8.7 g (n = 11), while those with continuous access to sucrose weighed 465.6 ± 15.3 g (n = 11), and those with intermittent access to sucrose weighed 466.9 ± 9.3 g (n = 10). Rats with continuous access to saccharin weighed 485.2 ± 14.7 g (n = 10) while those with intermittent access weighed 490.6 ± 8.2 g (n = 10).

3.2. Food/Fluid Consumption

Rats that drank only water ate an average of 22.1 g of chow per day throughout the experiment (Table 1). Food consumption decreased on days immediately following quinpirole tests, regardless of feeding condition, whereas fluid consumption was less affected by quinpirole tests (data not shown). Rats with continuous access to sucrose drank more than rats with continuous access to water (Table 1). Similarly, rats drinking sucrose ate less than rats drinking water. On days when sucrose was available, rats with intermittent access to sucrose consumed similar amounts of fluid and food compared with rats that had continuous access to sucrose. On days when water was available, those rats consumed similar amount of fluid and food as rats drinking water continuously (Table 1).

Table 1.

Food and water consumption in rats with continuous access to water, sucrose, or saccharin, or intermittent access to sucrose or saccharin.

| Group | Average (± S.E.M.) Food consumption (g) |

Average (± S.E.M.) Fluid consumption (g) |

|---|---|---|

| Water | 22.1 (1.2) | 81.1 (15.3) |

| Continuous Sucrose | 10.6 (1.3) | 165.9 (18.3) |

| Continuous Saccharin | 23.3 (1.4) | 84.4 (12.0) |

| Intermittent Sucrose | ||

| During Sucrose Access | 13.0 (1.1) | 182.7 (13.8) |

| During Water Access | 20.5 (1.3) | 72.7 (11.4) |

| Intermittent Saccharin | ||

| During Saccharin Access | 25.6 (1.4) | 122.6 (17.8) |

| During Water Access | 23.4 (1.5) | 87.7 (14.4) |

Bolded values are significantly different from rats drinking water (one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons)

Rats with continuous access to saccharin drank and ate similar amounts as rats with continuous access to water (Table 1). Rats with intermittent access to saccharin drank more fluid on the first of each set of two days of having access to saccharin (resulting in greater average fluid consumption than rats with continuous access to saccharin on days when saccharin was available), although food consumption did not decrease on those days (Table 1).

3.3. Yawning

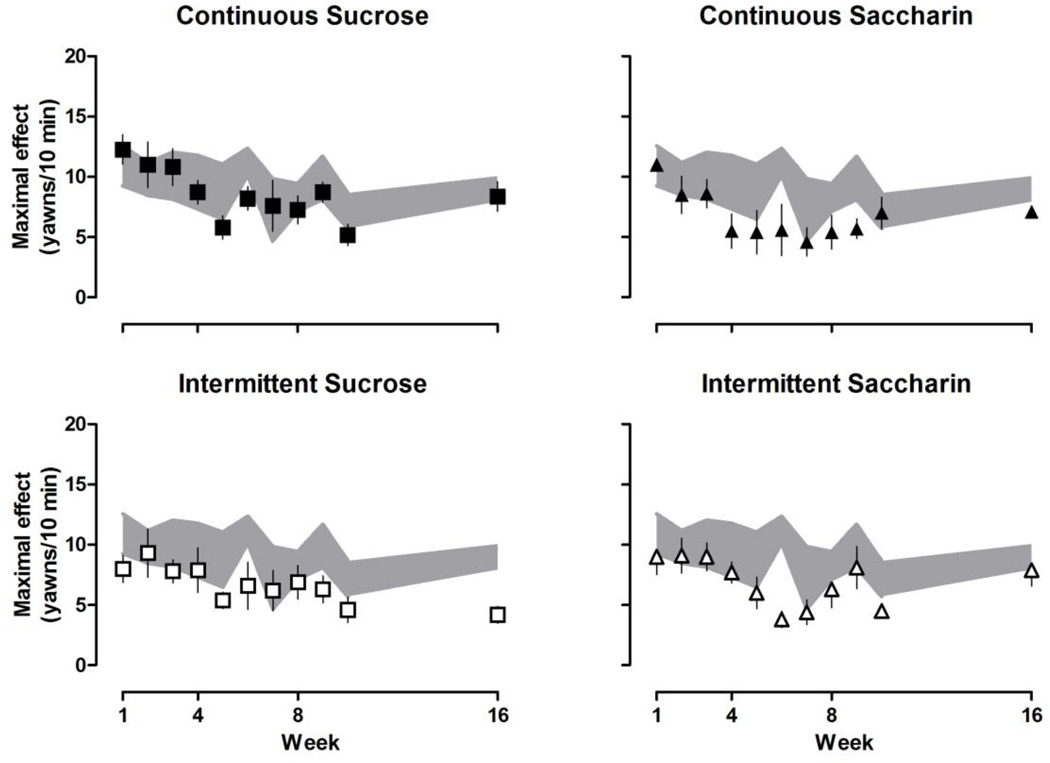

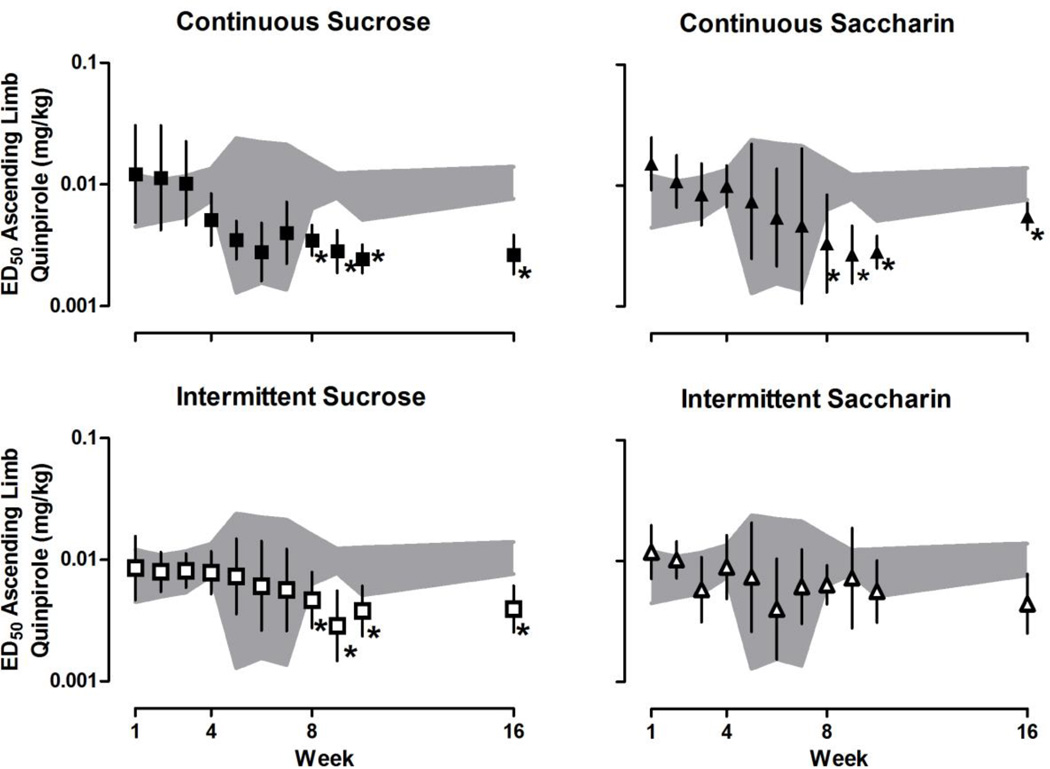

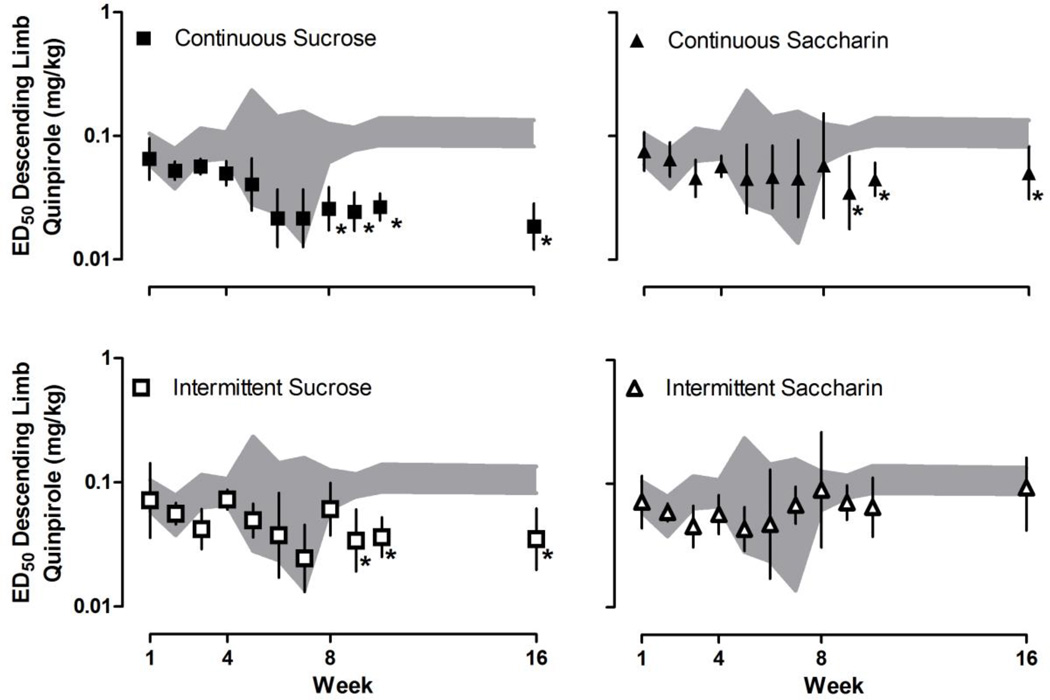

With increasing cumulative doses, quinpirole increased then decreased yawning (Fig. 1) resulting in an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve. The maximum number of yawns varied for individual rats across weeks [F (10, 487) = 8.02, P < 0.001], although the maximum average number of yawns did not differ significantly among groups. Maximal effect and ED50 values for both the ascending and descending limbs of the quinpirole dose-response curve were determined for individual rats (data not shown). The maximum average number of yawns for each group is shown in Fig. 2. Until week 8, quinpirole yawning dose-response curves were not different among groups (i.e., after 8 weeks of continuous access to water, sucrose or saccharin, or 8 weeks of intermittent access to sucrose or saccharin). A repeated measures ANOVA analyzing the ascending limbs of the quinpirole dose-response curve (Fig. 3) revealed a significant main effect of week [F (10, 487) = 11.90, P < 0.001] and a significant group by week interaction [F (40, 487) = 1.76, P = 0.0204]. A repeated measures ANOVA analyzing the descending limbs of the quinpirole dose-response curve (Fig. 4) revealed a significant main effect of week [F (10, 487) = 5.39, P < 0.001], group [F (4, 487) = 9.57, P < 0.001] and a significant group by week interaction [F (40, 487) = 2.48, P < 0.001]. Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons revealed that by week 8, both the ascending and descending limbs of the quinpirole dose-response curve were shifted significantly to the left in rats drinking sucrose (Figs. 3 and 4, upper left panels), compared with rats drinking water (P < 0.05). That is, ED50 values for both the ascending and descending limbs of the quinpirole dose-response curve were significantly smaller for rats with continuous access to sucrose, indicating that drinking sucrose shifted the dose-response curve leftward. This effect was consistent through week 16. By week 8, the ascending and not the descending limb of the quinpirole dose-response curve was also shifted to the left in rats with continuous access to saccharin (Figs. 3 and 4, upper right panels); however, by week 9 the descending limb also shifted to the left compared with rats drinking water (Fig. 4, upper right panel). Similarly, in week 8 the ascending limb was shifted to the left for rats with intermittent access to sucrose (Fig. 3, lower left panel), and by week 9 the descending limb also was shifted to the left, compared with rats drinking water (Fig. 4, lower left panel). Results from rats with intermittent access to saccharin were not significantly different from rats drinking water through week 16 (Figures 3 and 4, lower right panels).

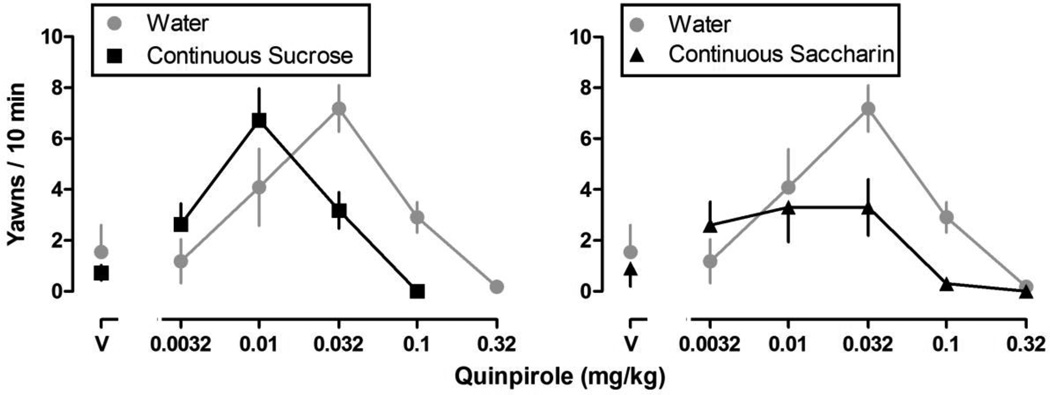

Fig. 1.

Average (± S.E.M.) yawns observed in a 10-min observation period in rats with continuous access to sucrose (left panel), saccharin (right panel), or water (both panels) for 8 weeks. Data are the average number of yawns (ordinate) plotted as a function of dose, in mg/kg body weight, of quinpirole (abscissae; V = vehicle; n = 10–11/ group). Both the ascending and descending limbs of the quinpirole dose-response curve were shifted to the left in rats drinking sucrose or saccharin, compared with rats drinking water. Data for rats with continuous access to water (± S.E.M.; gray shared area) are repeated in each panel.

Fig. 2.

Average (± S.E.M.) maximal effect (yawns observed in a 10-min observation period) in rats with continuous access to sucrose (upper left) or saccharin (upper right) or intermittent access to sucrose (lower left) or saccharin (lower right) plotted as a function of week on that fluid access condition. Data for rats with continuous access to water (± S.E.M.; gray shared area) are repeated in each panel. Only one cohort of rats was tested in weeks 5–7 (n = 5/group); for all other tests n = 10–11/group.

Fig. 3.

Average (95% confidence limits) ED50 for the ascending limb of the quinpirole dose-response curve in rats with continuous access to sucrose (upper left) or saccharin (upper right) or intermittent access to sucrose (lower left) or saccharin (lower right) plotted as a function of week. Data for rats with continuous access to water (upper and lower 95% confidence limits; gray shaded areas) are repeated in each panel. Only one cohort of rats was tested in weeks 5–7 (n = 5/group); for all other tests n = 10–11/group). *=statistically different from rats drinking water (P <0.05).

Fig. 4.

Average (95% confidence limits) ED50 for the descending limb of the quinpirole dose-response curve in rats with continuous access to sucrose (upper left) or saccharin (upper right) or intermittent access to sucrose (lower left) or saccharin (lower right) plotted as a function of week. Data for rats with continuous access to water (upper and lower 95% confidence limits; gray shaded areas) are repeated in each panel. Only one cohort of rats was tested in weeks 5–7 (n = 5/group); for all other tests n = 10–11/group). *=statistically different from rats drinking water (P <0.05).

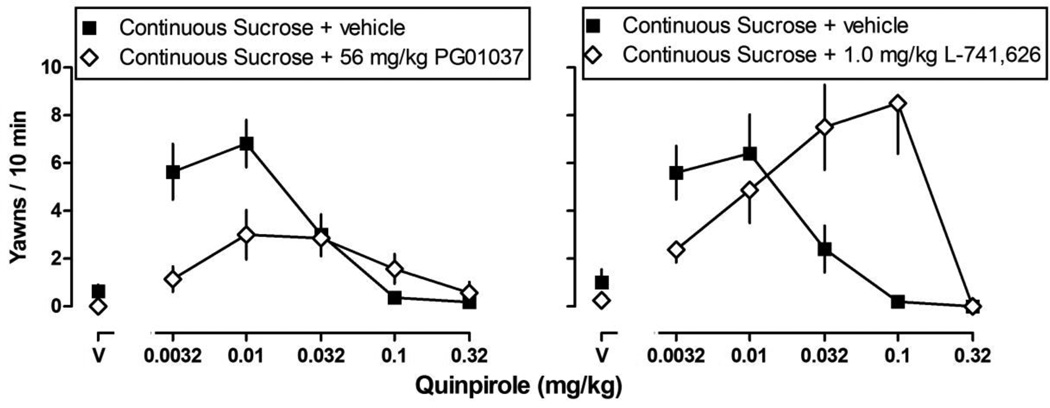

Each of the dopamine receptor antagonists shifted the quinpirole dose-response curves similarly across groups; thus, representative data are plotted only for the group of rats with continuous access to sucrose (Fig. 5). The dopamine D3 receptor selective antagonist PG 01037 (56.0 mg/kg) shifted the ascending limb of the quinpirole dose-response curve significantly downward (P < 0.05; Fig. 5; left panel); the descending limb of the quinpirole dose-response curve was not significantly impacted by PG 01037. The dopamine D2 receptor selective antagonist L-741,626 (1.0 mg/kg) shifted the descending limb of the quinpirole dose-response curve significantly to the right (P < 0.05; Fig. 5; right panel); the ascending limb was not significantly affected by L-741,626.

Fig. 5.

Average (± S.E.M.) yawns observed in a 10-min observation period in rats with continuous access to sucrose after pretreatment with vehicle (closed squares), the selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonist PG 01037 (left panel), or the selective dopamine D2 receptor antagonist L-741,626 (right panel). Data are presented as a percentage of the maximum number of yawns (ordinate) calculated for individual animals and plotted as a function of dose of quinpirole (abscissae; V = vehicle). Plotted are the combined data for both cohorts of rats (n = 10–11/group).

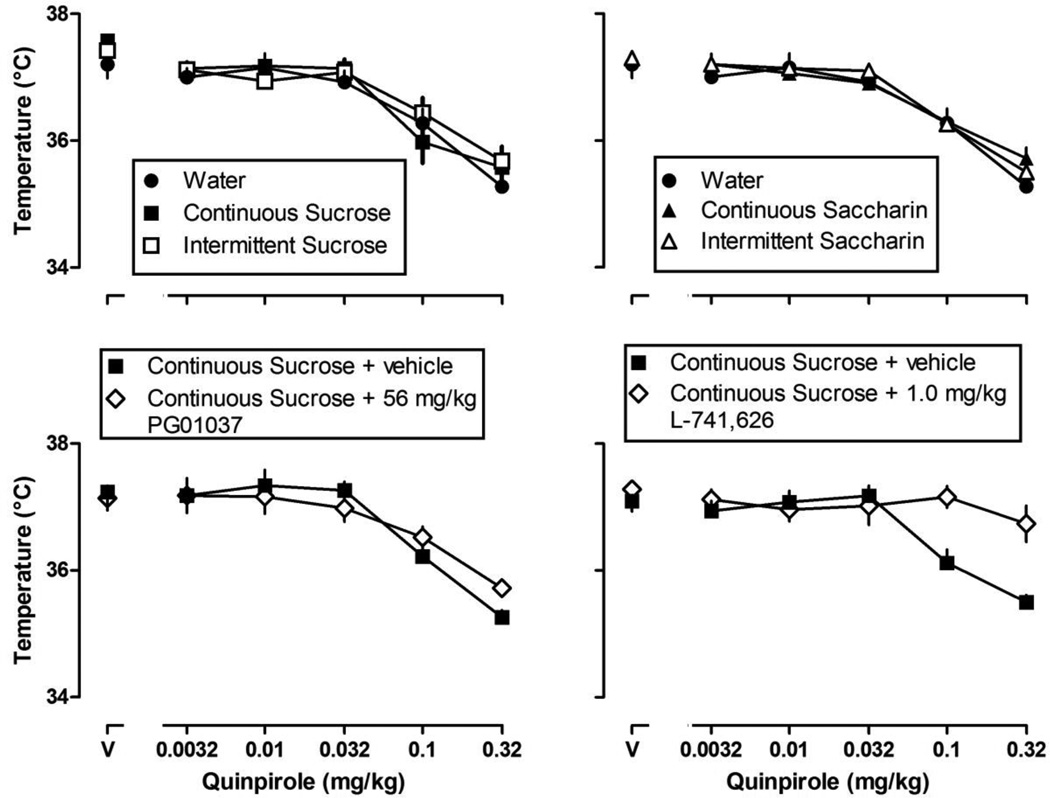

3.4 Body Temperature

Dose-response curves for quinpirole were determined once per week throughout the experiment. Under control conditions (i.e., while drinking water) and after the administration of saline, body temperature was not different among groups. Increasing doses of quinpirole decreased body temperature in all rats (P < 0.05; Figure 6; upper panels). Because quinpirole decreased body temperature similarly in all groups, representative data are plotted only for rats with continuous access to sucrose (Fig. 6; lower panels). The dopamine D2 receptor selective antagonist L-741,626 significantly attenuated quinpirole-induced hypothermia (Fig. 6; lower right panel) while the dopamine D3 receptor selective antagonist PG 01037 did not (Fig. 6; lower left panel).

Fig. 6.

Upper panels: average (± S.E.M.) body temperature of rats with continuous or intermittent access to sucrose (upper left) or with continuous or intermittent access to saccharin (upper right) after 8 weeks in the study. For comparison, data from rats with continuous access to water (closed circles) are repeated in both upper panels. Lower panels: average body temperature for rats with continuous access to sucrose after pretreatment with vehicle (closed squares), the selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonist PG 01037 (lower left), or the selective dopamine D2 receptor antagonist L-741,626 (lower right). Data in all four panels are presented as average body temperature (ordinate) plotted as a function of dose of quinpirole (abscissae; V = vehicle; n = 10–11/group).

4. Discussion

It is well established that sensitivity to the behavioral effects of quinpirole is enhanced in rats drinking sucrose (Baladi et al., 2011b); however, it was not known whether continuous access is necessary, or if intermittent access to sucrose is sufficient to cause such changes. Moreover, sucrose is high in calories and it is not known whether consumption of non-caloric sweet solutions might also change the sensitivity of rats to the behavioral effects of quinpirole. This study examined the effects of continuous and intermittent access to sucrose or saccharin on sensitivity of rats to quinpirole-induced yawning. Rats with continuous access to a 10% sucrose solution were more sensitive than rats drinking water to quinpirole-induced yawning. Moreover, rats drinking a 10% sucrose solution only two days per week (i.e., intermittent access) also were more sensitive than rats drinking water to quinpirole-induced yawning, although to a lesser extent than those with continuous access to sucrose (i.e., significant leftward shift of the ascending limb only on week 8). Rats with continuous access to saccharin, but not rats with intermittent access to saccharin, were more sensitive than rats drinking water to quinpirole-induced yawning (similar shifts in ascending and descend limbs to those seen with intermittent sucrose group). These results are consistent with a previous report showing that consuming sucrose enhances sensitivity of rats to quinpirole-induced yawning (Baladi et al., 2011b) and they extend those results by revealing that intermittent access to sucrose is sufficient to significantly enhance sensitivity to quinpirole-induced yawning. These results further demonstrate that the non-caloric sweetener saccharin enhances sensitivity of rats to quinpirole, suggesting that highly palatable taste in the absence of calories is sufficient to change sensitivity to direct-acting dopamine receptor agonists such as quinpirole.

There were significant differences among some groups with regard to the enhanced sensitivity to quinpirole-induced yawning. For example, only in rats with continuous access to sucrose were both the ascending (D3 receptor mediated) and the descending (D2 receptor mediated; see Depoortere et al., 2009; Sanna et al.,2011, 2012) limbs of the quinpirole dose-response curve shifted leftward (Figures 3 and 4) in week 8. In contrast, only the ascending limb of the quinpirole yawning dose-response curve was shifted leftward in rats with intermittent access to sucrose (week 8). This difference regarding shifting one limb but not the other might be related to previous studies showing that the duration of access to a highly palatable diet determines the magnitude of effect on dopamine neurotransmission and on sensitivity to drugs acting on dopamine systems (Avena and Hoebel, 2003; Avena et al., 2008; Puhl et al., 2011; Spangler et al., 2004). By week 9, both the ascending and descending limbs of the quinpirole dose-response curve were significantly shifted to the left both in rats with intermittent access to sucrose and in rats with continuous access to saccharin. Previous studies have shown that feeding conditions can differentially impact the two limbs of the quinpirole yawning dose-response curve (similarly to what has been demonstrated with food restriction; Collins et al., 2008). However, by week 9, a leftward shift in both limbs of the dose-response curve was revealed in rats with intermittent access to sucrose, suggesting that a longer duration of access causes a greater shift in the dose-response curve. Although differences in sensitivity have been reported using a shorter duration of access to sucrose (Baladi et al., 2011b), in that study only the ascending limb of the quinpirole dose-response curve was shifted to the left. A final quinpirole dose-response curve generated in week 16 did not reveal any further change in sensitivity to quinpirole in any group, suggesting a potential ceiling effect with regard to the impact of sucrose or saccharin on sensitivity to the behavioral effects of quinpirole. It is not known if other concentrations of sucrose or saccharin might have resulted in different consumption or further impacted sensitivity to quinpirole.

Insulin resistance can develop in rats drinking sucrose or eating a high fat chow (Baladi et al., 2011a) and insulin signaling has been shown to regulate dopamine neurotransmission (Daws et al., 2011). However, it is not clear whether insulin resistance is necessary to change sensitivity to the behavioral effects of drugs acting on dopamine systems, since rats with restricted access to high fat chow (such that their body weights are not increased relative to control rats eating standard chow) are more sensitive to quinpirole (Baladi et al. unpublished observation), but do not develop insulin resistance (see Serafine et al., 2014 for an example in female rats). Similarly, in the present experiment rats drinking saccharin were more sensitive than rats drinking water to quinpirole-induced yawning, further suggesting that diet-induced enhancement in sensitivity to drugs acting on dopamine systems can occur in the absence of insulin resistance. That the hypothermic effects of quinpirole were not significantly altered by the feeding conditions used in this study is consistent with previous reports using highly palatable diets (e.g., high fat chow or sucrose; Baladi et al., 2011a, b). These results are also consistent with other reports demonstrating that D2 receptor antagonists attenuate dopamine agonist-induced hypothermia in rats (Chaperon et al., 2003; Collins et al., 2007; see Millan et al., 2000, 2008 for examples of D3 receptor antagonists modulating agonist-induced hypothermia in a different outbred rat strain) as well as in mice (Boulay et al., 1999a, b).

Intake of highly palatable foods often escalates when access is limited (Avena and Hoebel, 2003; Puhl et al., 2011). In the present study, food and fluid intake changed systematically between days when rats in the intermittent access groups drank water and days when they drank either sucrose or saccharin (Table 1); however, body weight gain was similar between rats with intermittent access and those with continuous access. Moreover, there was no evidence of escalated intake; in fact, rats with intermittent access to sucrose drank similar amounts across days throughout the duration of the experiment (data not shown). It is possible that a different schedule of intermittent access, similar to what was used by others (e.g., Avena and Hoebel, 2003; Puhl et al., 2011), might have escalated intake, changed patterns of consumption, or changed in sensitivity to quinpirole differently or to a greater extent.

The results of the present study add to the growing body of literature showing that changing feeding conditions, content or access conditions, can dramatically impact dopamine systems and sensitivity to drugs acting on those systems. Non-caloric sweeteners are often used in place of caloric sweeteners to reduce the risk of negative health consequences (i.e., diabetes, obesity) associated with sweeteners like sucrose. The results of the present study demonstrate that consuming non-caloric sweeteners might significantly impact dopamine systems. Many drugs, including those used clinically and those used recreationally, target dopamine systems; although consuming non-caloric sweeteners might reduce the risk of some adverse health consequences (e.g., obesity and diabetes), consuming saccharin or other non-caloric sweeteners could also change sensitivity to drugs in a manner that alters therapeutic effectiveness of drugs or vulnerability to abuse drugs. Given a continuing escalation in the consumption of foods high in fat and sugar across much of the world (e.g., USDA, 2010), it is becoming increasingly important to understand the impact of these dietary conditions on sensitivity to drugs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants K05DA017918 and T32DA031115]. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure/conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Avena NM, Hoebel BG. A diet promoting sugar dependency causes behavioral cross-sensitization to a low dose of amphetamine. Neuroscience. 2003;122:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Underweight rats have enhanced dopamine release and blunted acetylcholine response in the nucleus accumbens while binging on sucrose. Neuroscience. 2008;156:865–871. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, Daws LC, France CP. You are what you eat: influence of type and amount of food consumed on central dopamine systems and the behavioral effects of direct- and indirect-acting dopamine receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 2012a;63:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, France CP. Eating high-fat chow increases the sensitivity of rats to quinpirole-induced discriminative stimulus effects and yawning. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21:615–620. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833e7e5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, Koek W, Aumann M, Velasco F, France CP. Eating high fat chow enhances the locomotor-stimulating effects of cocaine in adolescent and adult female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2012b;222:447–457. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, Newman AH, France CP. Influence of body weight and type of chow on the sensitivity of rats to the behavioral effects of the direct-acting dopamine-receptor agonist quinpirole. Psychopharmacology. 2011a;217:573–585. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, Newman AH, Thomas YM, France CP. Drinking sucrose enhances quinpirole-induced yawning in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2011b;22:773–778. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32834d0f3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay D, Depoortere R, Perrault G, Borrelli E, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D2 receptor knock-out mice are insensitive to the hypolocomotor and hypothermic effects of dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1999a;38:1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay D, Depoortere R, Rostene W, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D3 receptor agonists produce similar decreases in body temperature and locomotor activity in D3 knock-out and wild-type mice. Neuropharmacology. 1999b;28:555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaperon F, Tricklebank MD, Unger L, Neijt HC. Evidence for regulation of body temperature in rats by dopamine D2 receptor and possible influence of D1 but not D3 and D4 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:1047–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Calinski DM, Newman AH, Grundt P, Woods JH. Food restriction alters N’-propyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzothiazole-2,6-diamine dihydrochloride (pramipexole)-induced yawning, hypothermia, and locomotor activity in rats: evidence for sensitization of dopamine D2 receptor-mediated effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:691–697. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Newman AH, Grundt P, Rice KC, Husbands SM, Chauvignac C, Chen J, Wang S, Woods JH. Yawning and hypothermia in rats: effects of dopamine D3 and D2 agonists and antagonists. Psychopharmacology. 2007;193:159–170. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Witkin JM, Newman AH, Svensson KA, Grundt P, Cao J, Woods JH. Dopamine agonist-induced yawning in rats: a dopamine D3 receptor-mediated behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:310–319. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Anderson MM, Morgan AD. Higher locomotor response to cocaine in female (vs. male) rats selectively bred for high (HiS) and low (LoS) saccharin intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;88:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Morgan AD, Anker JJ, Perry JL, Dess NK. Selective breeding for differential saccharin intake as an animal model of drug abuse. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:435–460. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830c3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daws LC, Avison MJ, Robertson SD, Niswender KD, Galli A, Saunders C. Insulin signaling and addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:1123–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depoortere R, Bardin L, Rodrigues M, Abrial E, Aliaga M, Newman-Tancredi A. Penile erection and yawning induced by dopamine D2-like receptor agonists in rats: influence of strain and contribution of dopamine D2, but not D3 and D4 receptors. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20:303–311. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32832ec5aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosnell BA. Sucrose intake enhances behavioral sensitization produced by cocaine. Brain Res. 2005;1031:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundt P, Carlson EE, Cao J, Bennett CJ, McElveen E, Taylor M, Luedtke RR, Newman AH. Novel heterocyclic trans olefin analogues of N-{4-[4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]butyl}arylcarboxamides as selective probes with high affinity for the dopamine D3 receptor. J Med Chem. 2005;10:839–848. doi: 10.1021/jm049465g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Dekeyne A, Rivet JM, Dubuffet T, Lavielle G, Brocco M. S33084, a novel, potent, selective, and competitive antagonist at dopamine D(3)-receptors: II. Functional and behavioral profile compared with GR218,231 and L741,626. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:1063–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Svenningsson P, Ashby CR, Hill M, Egeland M, Dekeyne A, Brocco M, Di Cara B, Lejeune F, Thomasson N, Munoz C, Mocaer E, Crossman A, Cistarelli L, Giradon S, Iob L, Veiga S, Gobert A. S33138 [N-[4-[2-[(3aS,9bR)-8-cyano-1,3a,4,9b-tetrahydro[1]-benzopyrano[3,4-c]pyrrol-2(3H)-yl)-ethyl]phenylacetamide], a preferential dopamine D3 versus D2 receptor antagonist and potential antipsychotic agent. II. A neurochemical, electrophysiological and behavioral characterization in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:600–611. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl MD, Cason AM, Wojnicki FH, Corwin RL, Grigson PS. A history of bingeing on fat enhances cocaine seeking and taking. Behav Neurosci. 2011;125:930–942. doi: 10.1037/a0025759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna F, Succu S, Hubner H, Gmeiner P, Argiolas A, Melis MR. Dopamine D2-like receptor agonists induce penile erection in male rats: differential role of D2, D3 and D4 receptors in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Behav Brain Res. 2011;225:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna F, Succu S, Melis MR, Argiolas A. Dopamine agonist-induced penile erection and yawning: differential role of D2-like receptor subtypes and correlation with nitric oxide production in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus of male rats. Behav Brain Res. 2012;230:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafine KM, Bentley TA, Koek W, France CP. Eating high fat chow, but not drinking sucrose or saccharin, enhances the development of sensitization to the locomotor effects of cocaine in adolescent female rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000114. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler R, Wittkowski KM, Goddard NL, Avena NM, Hoebel BG, Leibowitz SF. Opiate-like effects of sugar on gene expression in reward areas of the rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;124:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. [Retrieved December 05, 2013];2010 http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/sites/default/files/dietary_guidelines_for_americans/PolicyDoc.pdf.