Abstract

Increasing evidence involves sustained pro-inflammatory microglia activation in the pathogenesis of different neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Parkinson's disease (PD). We recently uncovered a completely novel and unexpected role for caspase-8 and its downstream substrates caspase-3/7 in the control of microglia activation and associated neurotoxicity to dopaminergic cells. To demonstrate the genetic evidence, mice bearing a floxed allele of CASP8 were crossed onto a transgenic line expressing Cre under the control of Lysozyme 2 gene. Analysis of caspase-8 gene deletion in brain microglia demonstrated a high efficiency in activated but not in resident microglia. Mice were challenged with lipopolysaccharide, a potent inducer of microglia activation, or with MPTP, which promotes specific dopaminergic cell damage and consequent reactive microgliosis. In neither of these models, CASP8 deletion appeared to affect the overall number of microglia expressing the pan specific microglia marker, Iba1. In contrast, CD16/CD32 expression, a microglial pro-inflammatory marker, was found to be negatively affected upon CASP8 deletion. Expression of additional proinflammatory markers were also found to be reduced in response to lipopolysaccharide. Of importance, reduced pro-inflammatory microglia activation was accompanied by a significant protection of the nigro-striatal dopaminergic system in the MPTP mouse model of PD.

Keywords: microglia, Caspace-8, Parkinson's disease, lipopolysaccharide, MPTP

INTRODUCTION

Activated microglia play key roles in neuro-inflammation and depending on the nature of the initial stimulus their actions may be either beneficial or detrimental to neuronal function. In the latter case, activated microglia undergo phenotypic polarization toward a so called M1 pro-inflammatory phenotype and produce neurotoxic factors, such as inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), and glutamate [1, 2]. In contrast, activated microglia can be polarized into an anti-inflammatory phenotype defined as M2 phenotype expressing anti-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and unique membrane receptors [3, 4].

Chronic neuroinflammation involves the sustained activation of microglia, and consequent release of proinflammatory mediators, which are detrimental for the neuronal cell population. In chronic neuro-degenerative diseases, microglia remain activated for an extended period during which the production of mediators is sustained longer than usual, thus contributing to neuronal death. Compelling evidence suggests that inflammation plays an important role in the cell loss observed in Parkinson's disease (PD) [5–7]. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that incidence of idiopathic PD is about 50% lower in chronic users of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors than in age-matched non-users [8, 9]. Inflammation has been shown in different animal models of PD. Among them, the acute 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) model has been demonstrated to encompass a significant inflammatory response in the SN pars compacta (SNPC) along with degeneration of the nigro-striatal dopaminergic system [10–12]. LPS is the active immunostimulant in the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria that is responsible for triggering the cascade of events following bacterial infection [13, 14]. Interestingly, the SN is especially susceptible to the LPS-induced neurotoxicity as compared with other brain areas [15]. In this structure, the strong microglial response to LPS preceded the death of dopaminergic neurons [16, 17].

Caspases, a family of cysteinyl aspartate-specific proteases, are best known as executioners of apoptotic cell death and their activation are considered as a commitment to cell death ( [18]. However, certain caspases also function as regulatory molecules for immunity, cell differentiation and cell-fate determination [19].

We have described an unexpected novel function for caspases in the control of microglia proinflammatory activation and thereby neurotoxicity [20]. We showed that the orderly activation of caspase-8 and caspase-3/7, known executioners of apoptotic cell death, regulates microglia activation. We found that stimulation of microglia with various inflammogens activates caspase-8 and caspase-3/7 in absence of cell death in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, we also observed that these caspases are activated in microglia in the substantia nigra in PD subjects [20].

We aim at providing the genetic evidence that targeting CASP8 gene selectively in the microglia cell population in the brain can provide neuronal beneficial effect in animal models of PD. We have taken advantage of conditional knock-out genetic approaches in the myeloid system, including microglia in the brain, to examine cell-specific effects of caspase-8 signaling in the intranigral LPS model and the acute MPTP model of Parkinson's disease, well-established paradigms of dopaminergic neurodegeneration that induces a robust inflammatory response in the substantia nigra. In these models, we confirmed in vivo the importance of caspase-8 in regulating the proinflammatory response of activated microglia.

RESULTS

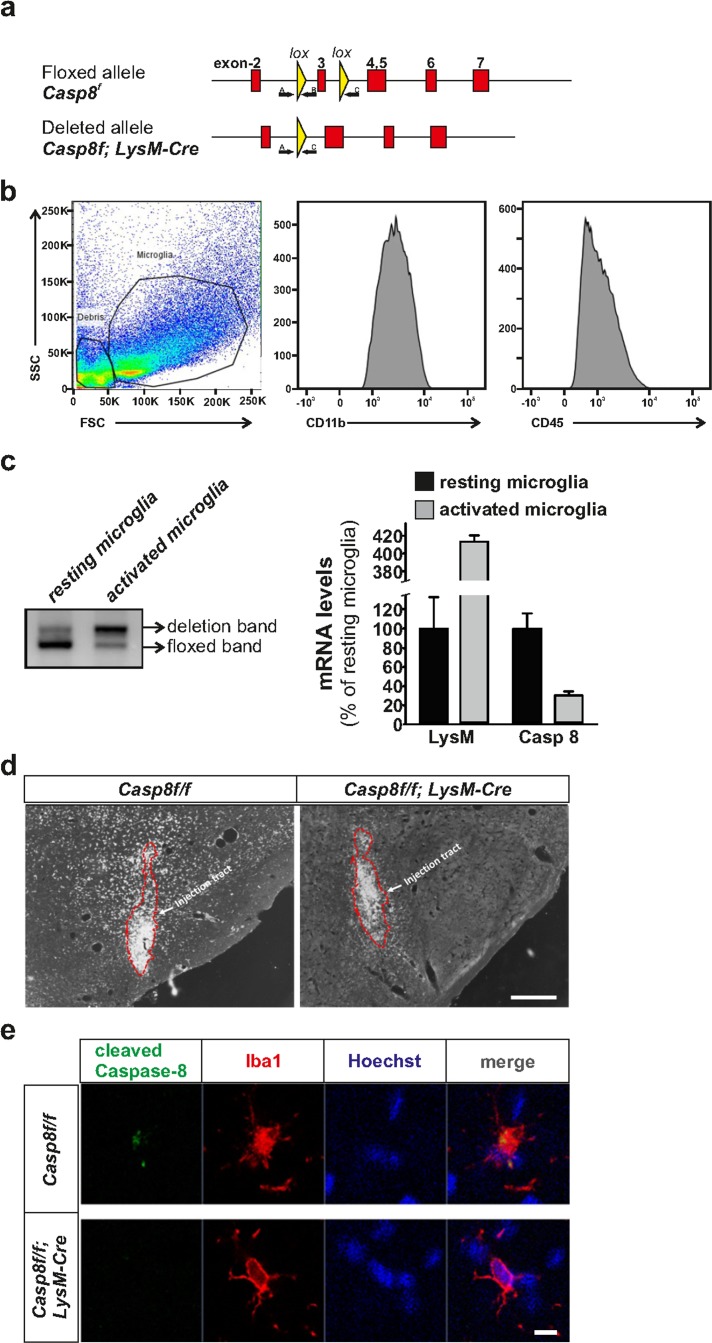

Generation of conditional caspase-8 knockout mice in myeloid cells and evaluation of caspase-8 gene deletion in resident and activated microglia

Caspase-8 floxed animals (Casp8fl/fl) expressing Lysoxyme 2 (LysM) Cre will be referred to as CreLysMCasp8fl/fl. Analysis of caspase-8 staining in the substantia nigra after LPS intranigral injection revealed a significant decrease in cleaved caspase-8 in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (Fig. 1d,e). We performed dual caspase-8 and Iba1 immunofluorescence after either intranigral LPS injection or MPTP administration. Cleaved caspase-8 immuofluorescence was detected in Iba1-positive cells of Casp8fl/fl mice after stimulation with either LPS or MPTP. Reduced cleaved caspase-8 staining was observed in Iba1-positive cells of CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice, confirming the depletion of caspase-8 in brain myeloid cells (Fig. 1e). Some concerns have been recently raised concerning the use of CreLysM mice to specifically target adult microglia [21]. Previous studies reported a high rate of recombination in brain microglia when using these mice [22, 23]. In contrast, an average recombination rate of about 45% was obtained in Iba1-labelled resident microglia from CreLysM mice. However, our immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated an almost absence of cleaved caspase-8 immunoreactivity in reactive microglia, suggesting an effective deletion of Caspase-8 gene in those cells in the CreLysM mice. Ascertaining the rate of Caspase-8 gene deletion in our experimental conditions is of critical importance considering the modest degree of recombination reported by Goldmann et al [21]using CreLysM mice. We wondered whether resting and activated microglia could exhibit different rates of gene deletion in the CreLysM mice. To achieve that, we isolated microglia from the ventral mesencephalon from intact and LPS-injected mice. Microglia were immunopurified using CD-11b-labelled microbeads after myelin removal by Percoll treatment. The purity of the microglia preparation was evaluated by flow cytometry analysis using CD-11b and CD-45 antibodies (Fig. 1b). Genomic DNA was isolated from resting and activated microglia and deletion of the Caspase-8 floxed sequence was evaluated following an ABC primer strategy. While primers A and B detect the floxed sequence, primers A and C do not amplify unless the floxed sequence is deleted (Fig. 1a). We have recently developed mice in which one of the caspase-8 alleles was knocked out (50% deletion). Microglia isolated from these mice was used to normalize the QPCR analysis. By using this approach, resident microglia from CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice rendered an extremely low level of Caspase-8 gene deletion (7.1 ± 3.2%), a level even lower than that reported by Goldmann et al [21]. In contrast, activated microglia obtained from the ventral mesencephalon from LPS-injected animals showed a very high rate of Caspase-8 gene deletion (75.4 ± 10.2) (Figure 1). A similar approach has been previously employed by Cho and coworker [24]. Indeed, the authors stimulated CreLysMIKKβf/f mice in vivo by i.c.v LPS injection and kainic acid injection, and demonstrated that the deletion rate is notably increased upon microglia activation. Furthermore, the authors demonstrated significantly less proinflammatory microglia activation in the mice subjected to kainic acid treatment [24]. To further validate the efficiency of Caspase-8 gene deletion, we analyzed the mRNA levels of Lysozyme M and caspase-8 from microglia isolated from the ventral mesencephalon 24 h after intranigral LPS injections. As seen in Fig. 1c, Lysozyme M mRNA levels were robustly up-regulated in activated microglia. Under these conditions, caspase-8 mRNA levels dropped to 30% of levels of resident microglia obtained from C CreLysMCasp8fl/fl reLysMCasp8fl/fl CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Due to tissue dissecting limitations, it is reasonable to assume that not all microglia isolated from the ventral mesencephalon from LPS-injected animals are activated. Consequently, we may conclude that CreLysMmice are valid to target adult microglia under experimental conditions leading to proinflammatory activation.

Figure 1. Generation of CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice and validation of Caspase-8 deletion.

Panel (a) contains a schematic illustration of the mouse genomic locus showing the insertion of the targeted allele flanked with LoxP sites (upper), and the deleted allele after Cre recombination (lower). Locations of primers A, B and C used for the PCR deletion study are also shown. Flow cytometry demonstrating the purity of the microglial fraction (b) used to assess the degree of caspase-8 gene deletion (c) based on an ABC primer strategy. The degree of gene caspase-8 gene deletion was evaluated in mesencephalic resident and activated microglia. QPCR demonstrated a low caspase-8 gene deletion in resident microglia and a dramatic increase in activated microglia. mRNA analysis of Lysozyme 2 and caspase-8 in microglia isolated from the ventral mesencephalon from CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice corroborated the striking differences between resident and activated microglia (c). Panel (d) shows immunohistochemistry of cleaved caspase-8 in the ventral mesencephalon of Casp8fl/fl and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice after intranigral LPS injection. Panel (e) shows immunofluorescence of cleaved caspase-8 and Iba1 showing co-staining in MPTP-injected Casp8fl/fl mice, and absence of cleaved caspase-8 staining in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (f). Scale bar: e: 300 μm; f: 20 μm.

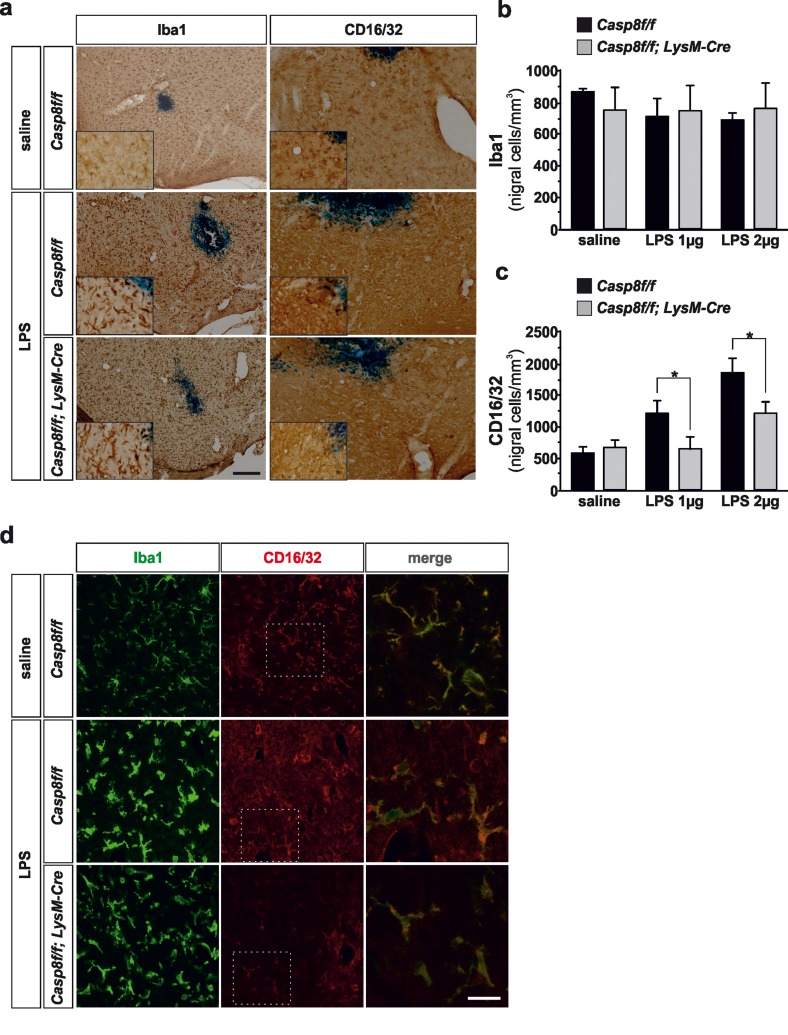

Caspase-8 deletion in myeloid cells blocks microglia activation in LPS neuroinflammatory model

As a first approach, we used intranigral injections of LPS, a major endotoxin acting as a ligand of TLR4 and known to induce a classically proinflammatory activation of microglia. Intranigral injection of LPS has been shown to induce an extensive activation of microglia along with degeneration of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons [16, 25].

Immunohistochemistry analysis of microglia/macro-phage population

Tissues were immunostained with Iba1, a pan specific marker of microglia/macrophages and CD16/32, a specific marker for the proinflammatory phenotype. We analyzed the effect of two in vivo doses of LPS, 2 and 4 μgs. Caspase-8 inhibition in LPS-induced activated microglia has been shown to induce necroptosis [26, 27], a RIPK1/RIPK3-dependent process [28, 29]. Analysis of microglia using Iba1 did not show differences in Cre CreLysMCasp8fl/fl LysMCasp8fl/fl mice as compared with Casp8fl/fl mice in response to LPS (Fig. 2a, b), an indication that necroptosis was not occurring in our experimental conditions. Upon LPS treatment, there was a marked microglia morphological change as characterized by Iba1 reactivity; further thickening of processes, retraction of finer ones, increased cell body size and Iba1 reactivity (Fig. 2a, d). In addition, numerous amoeboid-shaped cells could be observed in LPS-injected animals in both Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Since Iba1 does not clearly discern between resident and activated microglia, we used a specific marker for the proinflammatory phenotype of microglia, CD16/32 [30–32]. CD16/32 was significantly up-regulated in Iba-1-labeled microglia from Casp8fl/fl mice (Fig. 2d). However, this LPS-induced up-regulation of microglial CD16/32 was significantly attenuated in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (Figs. 2a, b, d and 3a). Dual immunofluorescence of Iba1 and CD16/32 demonstrated that upon saline injection there was some degree of microglia activation characterized by increased ramification of cytoplasmic process and cell size and enhanced Iba1 labeling (Fig. 2d). Under these conditions, most if not all CD16/32 positive cells were also positive for Iba1 (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. Microglial caspase-8 deficiency ameliorates proinflammatory microglia activation in the substantia nigra in response to intranigral LPS injection.

Panel (a) shows an illustration of Iba1 and CD16/32-labeled microglia in the ventral mesencephalon in response to either saline or intranigral LPS in Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. The effect of LPS and caspase-8 deficiency on the number of total microglia (Iba1) or proinflammatory microglia (CD16/32) in the substantia nigra is shown in panels (b) and (c). Results are the mean ± SD of a minimum of four independent experiments and are expressed as number of cells per mm2. Statistical significance was calculated by analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test for multiple range comparisons (p <0.05). Panel (d) shows an illustration of dual immunofluorescence of Iba1 and CD16/32-labeled microglia in the ventral mesencephalon in response to saline or intranigral LPS in Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Merge photographs shown in (d) are higher magnification photographs of dot boxes depicted in the left column. Note the completely different morphological features of microglia in response to saline or LPS (d). No apparent differences in terms of Iba1 were detected between Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (a, b, d). Also note the specific labeling of CD16/32, a proinflammatory marker of microglia activation, which is located in the membrane of microglia (d). Also note how the expression of CD16/32 is clearly down-regulated in response to caspase-8 deficiency (a, c, d). Scale bar: a, 100 μm; d: Iba1 and CD16/32 staining: 50 μm; merge: 20 μm.

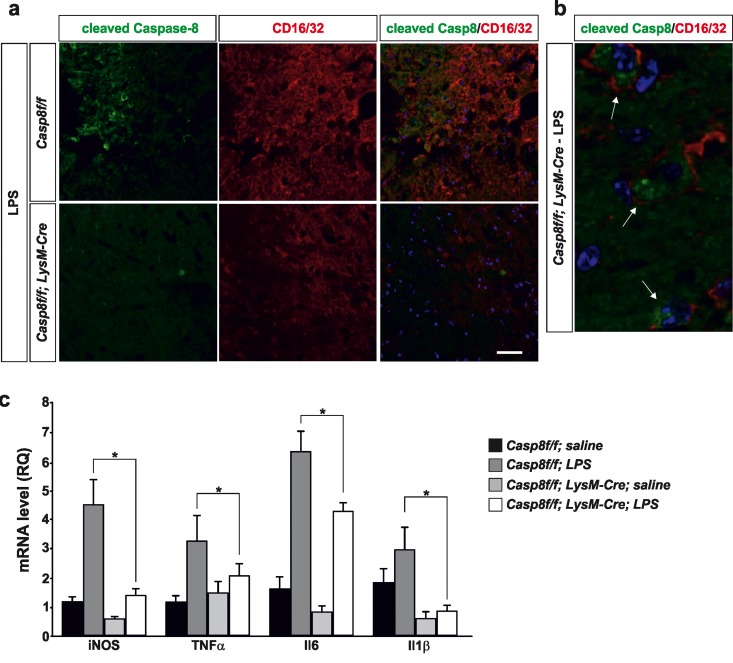

Figure 3. Caspase-8 is activated in viable CD16/32-immunolabeled microglia in substantia nigra in response to intranigral LPS injection, which is associated to higher key proinflammatory microglial markers.

Panel (a) shows an illustration of dual immunofluorescence of cleaved caspase-8 and CD16/32 in substantia nigra in response to intranigral LPS in Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Note how cleaved caspase-8 labeling is mostly associated to CD16/32-labeled microglia, which is dramatically decreased in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Panel (b) shows higher magnification photograph of that shown in panel (a) demonstrating active caspase-8 within viable CD16/32-immunolabeled microglia in Casp8fl/fl mice after LPS. Panel (c) shows the effect of LPS on mRNA expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), tumour necrosis factor α (TNF- α), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1β in substantia nigra of Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. mRNA levels were measured by quantitative PCR. Results are mean ± SD of at least four independent experiments and are expressed as relative quantification (RQ), calculated using the delta Ct method. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test for multiple range (p <0.05). As expected, LPS injection increased the expression levels of mRNA in Casp8fl/fl mice (WT). This induction was highly prevented in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (KO). Note the extremely low levels of IL-1β in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Scale bar: a: 30 μm; b: 10 μm.

Analysis of cleaved caspase-8 in proinflammatory microglia after LPS

We then analyzed the extent of active cleaved caspase-8 in activated microglia in the ventral mesencephalon in response to LPS injection. We found a widespread distribution of cleaved caspase-8 cells in LPS-injected Casp8fl/fl mice (Fig. 3a, b). In CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice, the labeling of cleaved caspase-8 was extremely low (Fig. 3a). Considering that we used conditional CASP8 knock out mice, our data suggest that under conditions of proinflammatory microglia activation, there is a selective activation of caspase-8 within microglia/macrophages. This observation is in line with our previous data demonstrating selective activation of caspase-8 in reactive microglia in the ventral mesencephalon from PD patients [20]. To demonstrate this, we performed double cleaved caspase-8 and CD16/32 immunofluorescence. The analysis demonstrated that most cleaved caspase-8 labeling in LPS-injected Casp8fl/fl mice was restricted to CD16/32-labeled microglia (Fig. 3a, b).

QPCR analysis of proinflammatory mediators

Previous short-term temporal analysis revealed that the highest induction of cytokines occurred 6 h after the LPS-injection, with a decrease at 48 h [25]. Consequently, we analysed key proinflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL) IL-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) along with iNOS in the ventral mesencephalon from either Casp8fl/fl mice or CreLys CreLysMCasp8fl/fl MCasp8fl/fl mice 6 h after injection of 2 μg LPS. As expected, LPS injection induced significant up-regulation of all proinflammatory markers in Casp8fl/fl mice animals in response to LPS (Fig. 3c). Strikingly, CreLysM Casp8fl/fl mice significantly prevented LPS-induced up-regulation of all pro-inflammatory markers analysed (Fig. 3c). Of note, iNOS levels in response to LPS, a prototypic M1 marker, ranged from 4.5-fold in Casp8fl/fl mice to 1.25-fold in Cr CreLysMCasp8fl/fl eLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (as compared with saline levels from Casp8fl/fl mice) (Fig. 3c). IL-1β levels in response to LPS ranged from near 3-fold in Casp8fl/fl mice to 0.8-fold in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (as compared with saline levels of Casp8fl/fl mice) (Fig. 3c).

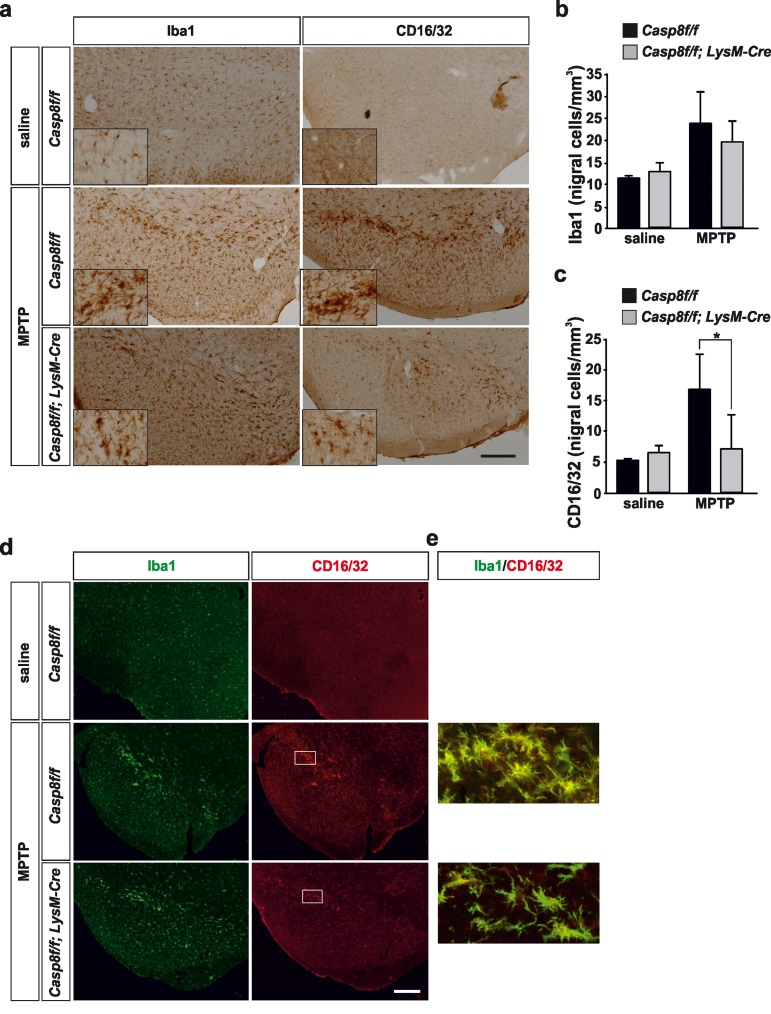

Caspase-8 deletion in myeloid cells blocks microglia activation in MPTP Parkinson's disease model

We have previously demonstrated i) a significant disruption of the blood brain barrier in response to intranigral LPS injections, ii) a significant peripheral infiltration in nigral tissue [33], a view supported in double transgenic mouse expressing GFP-tagged microglia and RFP-tagged monocytes (unpublished observations). Consequently, we decided to use the MPTP model, which is associated to a minimal blood brain barrier disruption, thus mimicking vascular conditions in PD [34, 35]. The MPTP acute mouse model trigger degeneration of nigro-striatral dopaminergic neurons along with significant brain inflammatory response [36, 37]. Besides, it has been demonstrated that resident microglia predominate over infiltrating myeloid cells in the MPTP mouse model of PD [38] thus making this model very suitable when studying the role of caspase-8 in microglia activation.

Immunohistochemistry analysis of microglia/macro-phage population in the nigro-striatal system

Under control conditions, typical resting microglia were distributed over the ventral mesencephalon in both Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (Fig. 4a, d). Stereological analysis demonstrated no differences between the two groups (Fig. 4b). Following acute MPTP administration, a significant increase in microglia density was detected in the ventral mesencephalon. No significant differences were found in terms of microglia density in the two experimental groups (Fig. 4a, b). Of note, microglia underwent drastic morphological changes especially in the SN pars compacta, these changes being more evident in Casp8fl/fl mice than in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (Fig. 4a, d). Further, most of these microglia located in the SNPC were morphologically round (Fig. 4a), thus suggesting a phagocytic status, most likely of degenerating dopaminergic nigral neurons.

Figure 4. Microglial caspase-8 deficiency ameliorates proinflammatory microglia activation in the substantia nigra in response to MPTP.

Panel (a) shows an illustration of Iba1 and CD16/32-labeled microglia in the substantia nigra in response to either saline or MPTP in Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Injection of saline in Casp8fl/fl mice was not different from CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice and hence only Casp8fl/fl mice saline is shown. Inserts are high-magnification photographs to show more precisely the morphological features of microglia. Panels (b) and (c) show the stereological analysis of total microglia (Iba1) (b) or proinflammatory microglia (CD16/32) (c) in the substantia nigra of Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice after MPTP. Results are the mean ± SD of a minimum of four independent experiments and are expressed as number of cells per mm3. Statistical significance was calculated by analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test for multiple range comparisons (p <0.05). Panel (d) shows illustration of dual immunofluorescence of Iba1 and CD16/32-labeled microglia in the substantia nigra in response to saline or MPTP in Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Panel (e) are higher magnification photographs of dot boxes depicted in Note the drastic changes in the microglia morphology in terms of Iba1-labeling in response to MPTP in both Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (a, d). Also note how CD16/32-immunolabeled proinflammatory microglia is strongly up-regulated in response to MPTP in Casp8fl/fl mice, particularly in the pars compacta of SN (a,d), this effect being notably hindered in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Scale bar: a: 350 μm; d: Iba1 and CD16/32 staining: 300 μm; merge: 35 μm.

As a further step, we analysed the phenotype of proinflammatory microglia in response to MPTP by means of CD16/32 immunohistochemistry. In Casp8fl/fl mice there was a remarkable similarity in terms of number and morphology between Iba1- and CD16/32-labelled cells in the ventral mesencephalon from MPTP-injected animals (Fig. 4a). Again, cells expressing high levels of CD16/32 were precisely located in the SNPC (Fig. 4a, d). In CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice, however, analysis demonstrated significantly less density of CD16/32-labeled cells in the ventral mesencephalon in response to MPTP, a clear indication of significant less proinflammatory microglia activation (Fig. 4c). Double Iba1 and CD16/32 immunofluorescence demonstrated that all these CD16/32-labelled cells were microglia (Fig. 4 d, e).

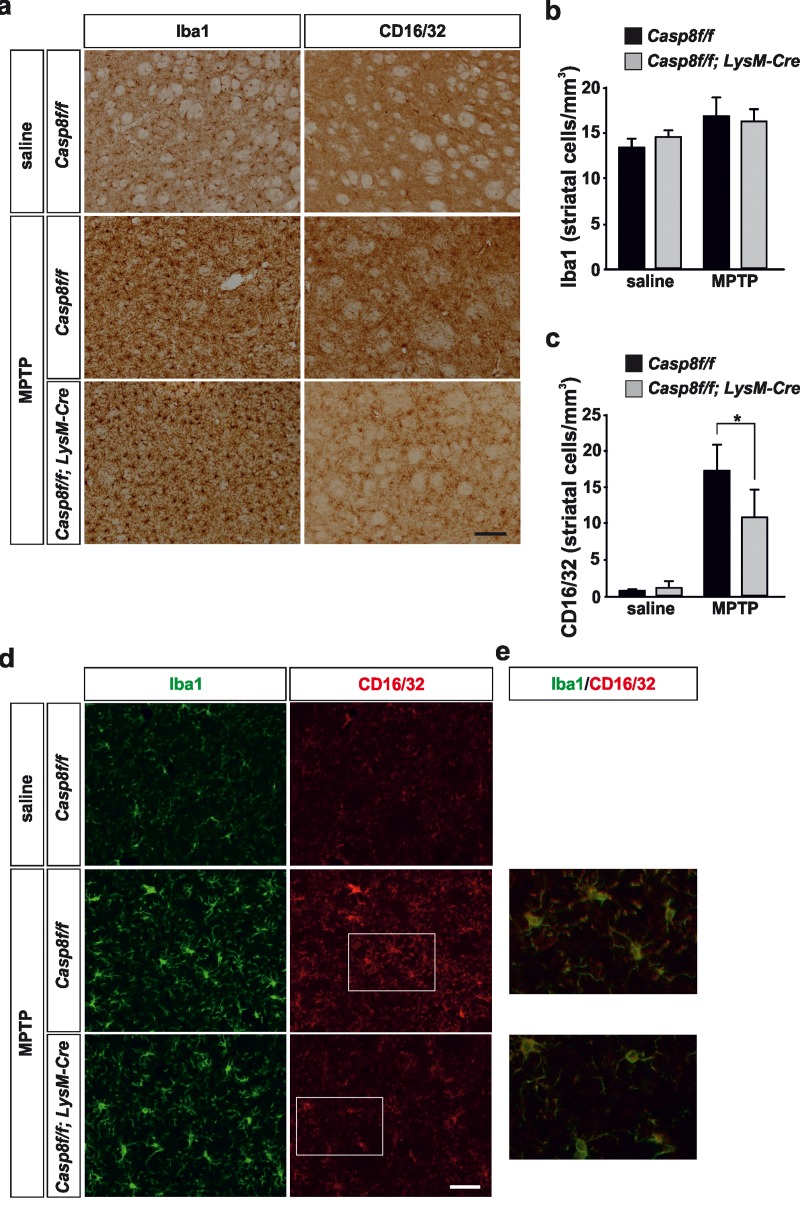

In the striatum, no significant differences were found in terms of density of Iba1-labeled microglia in saline-injected animals between Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (Fig. 5a, b, d). Similarly, the labelling of CD16/32 in striatum of saline-injected animals was very low in both experimental groups in accordance with a resting microglial phenotype (Fig. 5a, c, d). In response to MPTP, there were drastic changes in the striatal microglia population in both Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (Fig. 5a, b, d). However, when proinflammatory microglia activation was analysed in both groups, Casp8fl/fl mice showed significant higher density of CD16/32-labeled microglia as compared with CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (Fig. 5 a, c, d).

Figure 5. Microglial caspase-8 deficiency ameliorates MPTP-induced proinflammatory microglia activation in the striatum.

Panel (a) shows illustration of Iba1 and CD16/32-labeled microglia in the striatum in response to either saline or MPTP in Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Injection of saline in Casp8fl/fl mice was not different from CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice and hence only Casp8fl/fl mice saline is shown. Panels (b) and (c) show the stereological analysis of Iba1 (b) and CD16/32 (c) in the striatum in response to MPTP. Results are the mean ± SD of a minimum of four independent experiments and are expressed as number of cells per mm3. Statistical significance was calculated by analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference post hoc test for multiple range comparisons (p <0.05). Panel (d) shows illustration of dual immunofluorescence of Iba1 and CD16/32-labeled microglia in the striatum in response to either saline or MPTP in Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Panel (e) show higher magnification photographs of dot boxes depicted in panel (d). Note the drastic changes in the microglia population in terms of Iba1-labeling in response to MPTP in both Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (a,d). Note the low levels of CD16/32 labeling in the unlesioned striatum (a, c, d) and how this marker is robustly up-regulated in response to MPTP in Casp8fl/fl mice (a, c, d). Also note how the MPTP-induced up-regulation of proinflammatory microglia in tems of CD16/32 is hindered in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Scale bar: a: 125 μm; d: Iba1 and CD16/32 staining: 50 μm; merge: 20 μm.

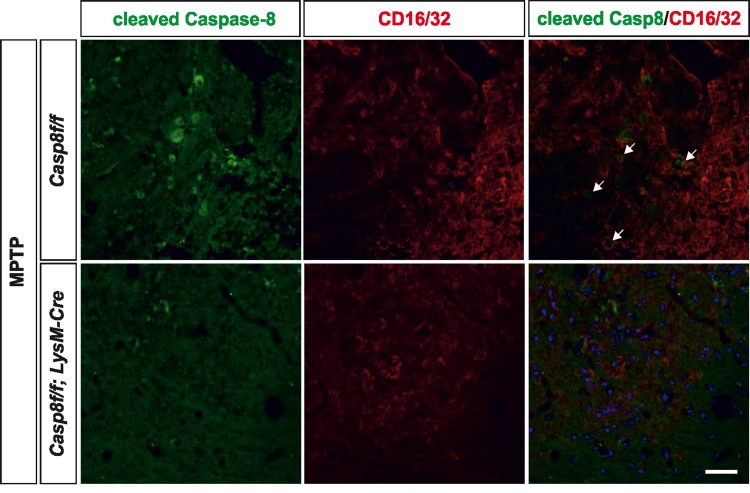

Analysis of cleaved caspase-8 in proinflammatory microglia after MPTP

We also analysed the extent of activated caspase-8 in the ventral mesencephalon 72 h after MPTP in both Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. In Casp8fl/fl mice, and found a widespread activation of caspase-8 in the ventral mesencephalon, which was highly but not totally abrogated in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice (Fig. 5d). Nevertheless, this observation also points out a precise association between caspase-8 activation and proinflammatory microglia. Phenotypic characterization of cleaved caspase-8 labelled cells demonstrated that most of them were also positive for CD16/32 in Casp8fl/fl mice. Most cleaved caspase-8 labelling in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice was localized in non-CD16/32-labeled cells (Fig. 6). However, a few cells were positive for both cleaved caspase-8 and CD16/32, which suggests that the rate of CASP8 gene deletion in microglia is high but not complete.

Figure 6. Caspase-8 is activated in viable CD16/32-immunolabeled microglia in substantia nigra in response to intranigral LPS injection, which is associated to higher key proinflammatory microglial markers.

Panel (a) shows illustration of dual immunofluorescence of cleaved caspase-8 and CD16/32 in substantia nigra in response to intranigral LPS in Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Note how cleaved caspase-8 labeling is mostly but not completely associated to CD16/32-labeled microglia, which is decreased in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. In both, Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice, some non-CD16/32-labeled cells express cleaved caspase-8. Arrows indicate viable proinflammatory CD16/32-labeled microglia expressing active caspase-8 in Casp8fl/fl mice after MPTP. Scale bar: 30 μm.

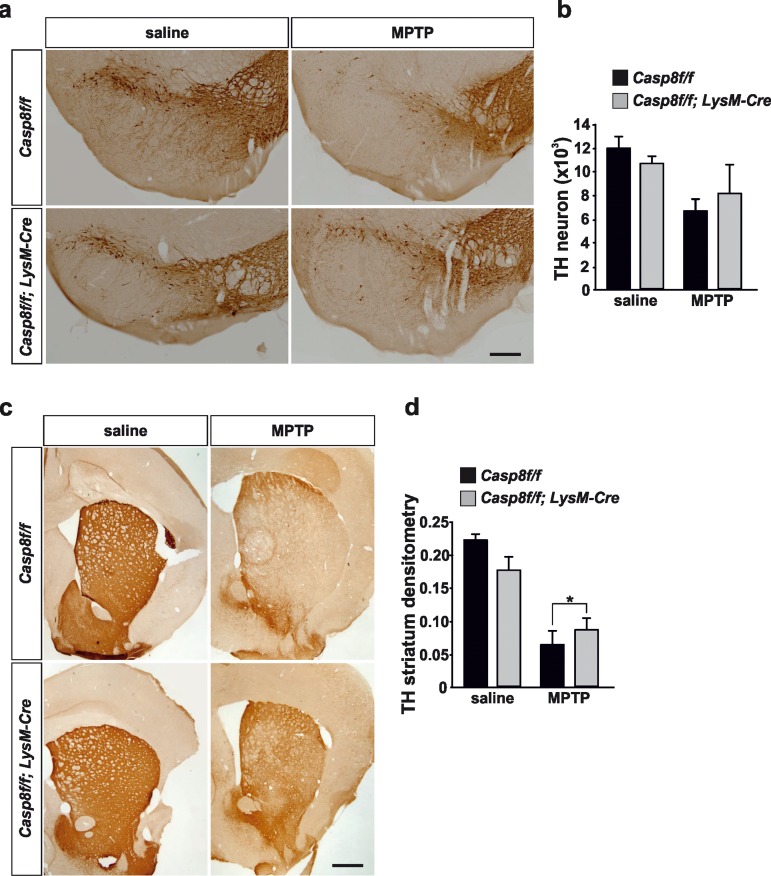

Analysis of the nigro-striatal dopaminergic system

We performed a stereological quantification of dopaminergic nigral neurons and a densitometric analysis of striatal dopaminergic nerve terminals. Acute MPTP administration reduced by 45% the total number of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-immunopositive neurons in the SN of Casp8fl/fl mice. In CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice, the reduction in TH-immunopositivity was 24%, with this effect being close to statistical significance (Fig. 7a, b).

Figure 7. Caspase-8 deficiency protects the nigro-striatal dopaminergic system against the MPTP-induced neurodegenerative changes.

Illustration of tyrosine-hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactivity in substantia nigra (a) and striatum (c) in response to either saline or MPTP in Casp8fl/fl and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Stereological quantification of TH-labeled neurons of each condition is shown in (b). There was less loss of nigra dopaminergic neurons in response to MPTP in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice, this effect being close to statistical significance. Analysis of integrity of striatal dopaminergic nerve endings (d) demonstrated significantly less MPTP-induced loss of TH immunoreactivity in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice as compared with Casp8fl/fl mice (p <0.05). Scale bar: a: 400 μm; c: 500 μm.

Analysis of striatal dopaminergic nerve terminal density demonstrated a 72% decrease in MPTP-injected Casp8fl/fl mice in comparison with saline-injected animals (Fig. 7c, d). However, in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice, the loss was significantly lower (47% as compared with saline-injected animals; p < 0.05) (Fig. 7c, d).

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated a significant role of caspase-8 and caspase-3/7 in the proinflammatory activation of microglia [20]. In this study, we have taken advantage of conditional caspase-8 KO mice specifically in the myeloid system to test the in vivo involvement of caspase-8 in microglia activation in animal models of Parkinson's disease. A recent study by Prinz and colleagues [21] analyzed the rate of recombination in resident microglia from CreLysMTAK1fl/fl mice reaching values (about 45%) far away from being optimal to undertake conditional gene deletions studies. However, a study by Cho et al [24] demonstrated that under conditions of microglia activation, the degree of gene deletion dramatically increases when using CreLysMl mice. We explored the possibility whether similar degree of gene deletion could be observed in activated microglia in our animal model. To achieve this, we isolated microglia from the ventral mesencephalon of CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Resident microglia were isolated from unlesioned animals and proinflamamatory activated microglia from intranigrally LPS-injected animals. The degree of Caspase-8 gene deletion in resident microglia was very low (about 7%), which is significantly less than that obtained in other studies using CreLysM mice [21, 24]. This observation may suggest a survival role of caspase-8 in resident microglia. Strikingly, a dramatic increase in the rate of Caspase-8 gene deletion was detected in proinflammatory activated microglia from the mesencephalon (about 75%), in accordance to an up-regulation of LysM in activated microglia. The QPCR analysis of caspase-8 fully supported the gene deletion study. Besides, upon intranigral LPS injection, a strong microglial up-regulation of cleavage caspase-8 was detected in the ventral mesencephalon of Casp8fl/fl mice, which was mostly abolished in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. Taken together, we conclude that CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice are valid to investigate the in vivo role of caspase-8 in proinflammatory microglia activation.

CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice did not show significant differences in terms of density of Iba1-labelled microglia in response to either intranigral LPS injection or acute MPTP injections. However, analysis of specific proinflammatory microglia demonstrated a negative correlation between levels of active caspase-8 and proinflammatory microglia activation, thus supporting the view that caspase-8 plays a significant role in inflamed microglia. In addition, the reduction of proinflammatory microglia activation seen in the MPTP mouse model of PD was accompanied by a significant protection of the nigro-striatal dopaminergic system in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice.

The main goal of this study was to demonstrate the gene involvement of caspase-8 in microglia-derived brain inflammation under in vivo conditions. CASP8 null animals are not viable due to embryonic lethality around embryonic day E10.5 [39] indicating a vital role for caspase-8 in embryonic development. Ablation of RIPK3 completely rescues the lethality of CASP8 deficient mice [29, 40]. These findings highlighted non-apoptotic survival roles of caspase-8 [41, 42]. Subsequent works demonstrated that caspase-8 suppresses a RIPK1-RIPK3-dependent programmed necrosis, also known as necroptosis [28, 43]. Recently, two independent groups demonstrated that inhibition of caspase-8 induces necroptosis in inflammatory activated primary microglia but not in neurons, astrocytes, or unactivated microglia [26, 27]. The question that arises from these observations is related to the existence or not of in vivo necroptosis of activated microglia under conditions of caspase-8 gene deletion. We tested two different animal models, intranigral LPS injections and the acute MPTP model. The substantia nigra shows a high density of resident microglia as compared with other brain areas [44] and more importantly, it has been demonstrated to be highly sensitive to proinflammatory stimuli including LPS [15, 16, 25]. Our analysis of microglia population in response to intranigral LPS injections using the pan microglia marker Iba1 did not detect significant differences in microglial numbers between Casp8fl/fl and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. The same was seen in the acute MPTP mouse model of PD. A robust but transient activation of microglia is observed shortly after using this model [10, 11], hence, analysis of microglia after MPTP was performed at 3 days postinjection. We failed to detect significant differences in terms of microglia density between Casp8fl/fl and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. It remains to be established if complete CASP8 gene deletion is needed to trigger necroptosis in activated microglia. It is noteworthy that primary rat activated microglia are more prone to trigger necroptosis than mouse activated microglia to TLR3/4 stimulation and caspase inhibition [27].

Very interestingly, the group by Guy Brown and colleagues besides demonstrating the existence of necroptosis in activated microglia in response to caspase-8 inhibition in vitro, they demonstrated that LPS and other proinflammogens activated caspase-8 in microglia without inducing apoptosis [26]. These results are in line with our previous observations that that activation of microglial cells with different proinflammogens led to modest but significant activation of caspase-8 activity in absence of significant cell death [20]. With these precedents, we analyzed the extent of cleaved caspase-8 in the ventral mesencephalon in two in vivo models, intranigral LPS and MPTP. Interestingly, significant caspase-8 cleavage was detected in viable activated microglia in the ventral mesencephalon in Casp8fl/fl mice in response to either intranigral LPS or MPTP. This caspase-8 activation was mostly abrogated in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice, thus highlighting non-apoptotic roles of caspase-8 in reactive microglia. These observations are in line with our previous observations when we analyzed postmortem brain tissue from patients who have been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in terms of protein expression of cleaved caspase-8 and the microglia marker CD68 and found significant cytoplasmic expression of active caspase-8 in the Parkinson's disease ventral mesencephalon [20].

We have previously demonstrated that chemical inhibition or gene knockdown of caspase-8 led to significantly less proinflammatory microglia activation in terms of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokine induction in response to different proinflammogens [20]. Consequently, we performed a QPCR analysis of key proinflammatory genes in the ventral mesencephalon in response to intranigral LPS in both Casp8fl/fl mice and CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice including iNOS, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β. Analysis was performed at 6 h after LPS, when most relevant changes take place. As expected, in Casp8fl/fl mice, LPS highly induced all markers examined as compared with saline-injected animals. Notably, all proinflammatory markers examined were significantly lower in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice than in Casp8fl/fl mice. Striking differences were found for iNOS and IL-1β. First, levels of both markers were constitutively lower in saline-injected CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice than in Casp8fl/fl mice. Second, levels of both markers were either not different (iNOS) or even lower (IL-1β) in LPS-injected CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice as compared with saline-injected Casp8fl/fl mice. Taken together, these results point to a dysregulated proinflamamtory microglia phenotype in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice.

Recent reports have demonstrated a novel role for caspase-8 as a negative upstream regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells and macrophages in a ripoptosome-dependent fashion [45–47]. Thus, in caspase-8 deficient cells, TLR activation triggers release of IL-1 β even in absence of ATP as stimulating factor [47]. In this process, RIPK is supposed to play a determinant role [47]. Consequently, in these cells the role of caspase-8 can be seen as anti-inflammatory. However, a direct role for caspase-8 in the production of biologically active IL-1β in response to TLR3 and TLR4 stimulation in bone-marrow derived macrophages has been documented [48], a view with fits well with our in vivo observations.

To shed further light in this issue, and considering that we did not find differences in terms of density of Iba1-labeled microglia between CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice and Casp8fl/fl mice in response to intranigral LPS, we decided to use a specific marker of M1 proinflammatory microglia, CD16/32 [3, 30, 32]. We confirmed that upon activation, microglia up-regulate expression of CD16/32 and more importantly, we found that density of CD16/32-immunolabeled cells was significantly lower in LPS-injected CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice than in LPS-injected Casp8fl/fl mice. Altogether, our results strongly suggest an anti-inflammatory role of caspase-8 in microglia-mediated brain inflammation.

As stated above, we detected a dysregulated LPS-induced iNOS expression in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice. It has been reported that expression of iNOS during inflammation in the CNS plays a role in the neurodegeneration in PD [49, 50]. Besides, Le et al. [51] showed that even though microglial activation results in the release of several cytokines and reactive oxygen species, only NO and H2O2 appeared to mediate the microglia-induced dopaminergic cell injury. Consequently, we decided to analyze CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice in the MPTP animal model of PD. Analysis were performed at 3 days postinjection when inflammatory response is maximal and when neurodegeneration of the nigro-striatal dopaminergic system is evident. Proinflammatory microglia was analyzed in terms of CD16/32 immunohistochemistry in both SN and striatum. The integrity of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system was analyzed by stereological analysis of nigral TH-labeled dopaminergic neurons in the SN or quantification of the density of the striatal dopaminergic nerve terminals. We found a remarkable up-regulation of CD16/32-immunolabeled cells in striatum and in the SN of Casp8fl/fl mice, this effect being especially evident in the pars compacta, where dopaminergic neurons are located. Double CD16/32 and Iba1 immunofluorescence demonstrated the microglia phenotype of most CD16/32-labeled cells. Strikingly, density of CD16/32-immunolabeled microglia was robustly attenuated in the nigro-striatal system of CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice in response to MPTP. We conclude that proinflammatory microglia activation is hindered in CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice.

iNOS-deficient mice are more resistant to MPTP-induced dopaminergic cell loss than their wild-type littermates [11]. In addition, minocycline, a tetracycline derivative that blocks microglial activation, prevented MPTP-induced upregulation of iNOS and dopaminergic cell loss in mice treated with the toxin [52, 53]. Our analysis of the dopaminergic system demonstrated a more preserved integrity of this system in MPTP-treated CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice as compared with Casp8fl/fl mice. These observations confirm and extend our previous observations using intranigral injections of IETD-fmk, a selective caspase-8 inhibitor [20] and highlight the neurotoxic role of proinflammatory activated microglia in dopaminergic degeneration.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the gene involvement of caspase-8 in proinflammatory microglia activation in two well defined animal models of inflammation and dopaminergic degeneration including intranigral LPS injection and acute MPTP treatment. Significant less neurotoxic microglia activation was seen in the nigro-striatal system of CreLysMCasp8fl/fl mice in response to both challenges. These results reinforce the view of caspase-8 as a key regulator of brain inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of myeloid specific Caspase-8 deficient mice

Caspase-8f/f C57BL/6 mice (with the CASP8 allele floxed at exon 3) were generously provided by Prof. Steven M. Hedrick (University of California, San Diego) [54] (Fig. 1a). C57BL/6 mice containing a Cre recombinase under the control of LysM promoter and enhancer elements, which allow its expression in the myeloid cell linage, including microglia, were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (strain name B6.129P2-Lyz2tm1(cre)Ifo/J). A cross was set up between both strains and the offspring were Casp8f/+.CreLysM+/−. These offspring were crossed with Casp8f/f to generate Casp8f/f.CreLysM+/− (myeloidCasp8KO mice) and Casp8f/f. CreLysM−/− (WT mice). In order to make the breeding process more efficient we crossed Casp8f/f. CreLysM+/− with Casp8f/f mice to generate a 50% Casp8f/f.CreLysM+/− and 50% Casp8f/f.CreLysM−/−. Homozygous floxed CASP8 mice were born at the predicted Mendelian ratio and were indistinguishable from littermates. Wild type, single, and double floxed targeted CASP8 alleles were genotyped by PCR.

Genotyping the mice

Genotyping of the mice was done by PCR analyses of tail DNA. For the PCR analyses, we used the oligonucleotides 5′-ATAATTCCCCCAAATCCTCGCATC-3′ (A, sense) and 5′-GGCTCACTCCCAGGGCTTCCT-3′ (B, antisense) for the floxed and wild type alleles (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA); and 5′-CTTGGGCTGCCAGAATTTCTC-3′ (LysM Cre Common), 5′-TTACAGTCGGCCAGGCTGAC-3′ (LysM Cre Wild Type) and 5′-CCCAGAAATGCCAGATTACG-3′ (LysM Cre mutant) for the Cre transgenes (Jackson Labs Technologies, Inc. Las Vegas, NV. 89134).

PCR and real-time PCR for assessing deletion efficiency in resting and activated microglia

The effectiveness of Cre-mediated deletion of the floxed caspase-8 allele was first roughly estimated by PCR in microglia isolated from the ventral mesencephalon from unlesioned (resting microglia) and from intranigrally LPS-injected animals (activated microglia) (see below).

Microglial cells were isolated from dissected ventral mesencephalon after perfusion with ice-cold PBS, weighed, and enzymatically digested using Neural Tissue Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec S.L. Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), in combination with the gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec S.L. Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), for 35 min at 37°C. Tissue debris was removed by passing the cell suspension through a 40 μm cell strainer. Further processing was performed at 4°C. After enzymatic dissociation, cells were resuspended in 30% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 700 g. The supernatant containing the myelin was removed, and the pelleted cells were washed with HBSS, followed by immunomagnetic isolation using CD11b (Microglial) MicroBeads mouse/human (Miltenyi Biotec S.L. Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). After myelin removal, cells were stained with CD11b (Microglial) MicroBeads in autoMACS™Running Buffer MACS separation Buffer (Miltenyi Biotec S.L. Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) for 15 minutes at 4°C. CD11b+ cells were separated in a magnetic field using LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec S.L. Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The CD11b+ fraction was collected and used for further analyses.

The isolated microglia was evaluated by FACS analysis. CD11b+ cells obtained from the isolation procedure were resuspended in PBS and immunostained with anti-CD45 and anti-CD11b antibodies (Miltenyi Biotec S.L. Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) for 10 minutes at room temperature. CD11b and CD45 antibodies were fluorochrome-conjugated with PacificBlue and FITC respectively, and used at final dilutions of 1:10 (Figure 1).

For evaluation of caspase-8 gene deletion efficiency, we followed an ABC primer strategy (see figure 1 for locations of primers). DNA was extracted from the microglial fraction and subjected to PCR analysis using three primers (A, B and C): 5′-ATAATTCCCCCAAATCCTCGCATC-3′ (A, sense for the wild-type, floxed, and deleted allele), 5′-GGCTCACTCCCAGGGCTTCCT-3′ (B, antisense for the wild-type, and floxed allele) and 5′-GCTACAGTGATGGTTTGTACATGG-3′ (C, antisense for the deleted allele) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA).

For more precise quantitative evaluation, the extent of deletion in resident and activated microglia were assessed by real-time PCR. DNA levels from each sample were normalized using microglia from mice in which one of the caspase-8 alleles was knocked out (50% deletion). Primers A and B were used to quantify the floxed undeleted caspase-8 gene whereas primers A and C were used to quantify the deleted caspase-8 gene. All samples were tested in triplicate. Ct were determined by plotting normalized fluorescent signal against cycle number, and the caspase-8 floxed and caspase-8 deleted copy number was calculated from the corresponding Ct values.

LPS intranigral injection

Animals had free access to food and water. Experiments were performed in accordance with the Guidelines of the European Union Council (86/609/EU), following Spanish regulations for the use of laboratory animals and approved by the Scientific Committee of the University of Seville. Experiments were performed in 2–4-month old age male animals. Mice were anaesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/Kg) and positioned in a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA) with a mouse adaptor. Intranigral LPS injections (from Escherichia coli, serotype 026:B6; Sigma) (2 μg in 1μl or 4 μg in 2 μl sterile saline) were made 1.2 mm posterior, 1.2 mm lateral and 5.0mm ventral to the lambda. For QPCR analysis, the SN was dissected from each mouse 6 h after the injection of saline or LPS, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. For immuno-histochemistry analysis, 24 h later, mice were transcardially perfused under isoflurane anesthesia with 4% paraformaldehyde, pH 7.4. Brains were removed, cryoprotected in sucrose and frozen in isopentane at −80°C and serial coronal sections (25 μm sections) covering the whole substantia nigra were cut with a cryostat and mounted on gelatin-coated slides and further processed for immunohistochemistry.

MPTP injections

Animals were treated with four injections of MPTP (16mg/kg) at 2 h intervals. Four days after the last injection, animals were sacrificed and brains processed for immunohistochemistry as already stated.

Immunohistological evaluation: Tyrosine hydroxylase, Iba-1, CD16/32 and cleaved caspase-8

Thaw-mounted 25-μm coronal sections were cut on a cryostat at −15 °C and mounted in gelatin-coated slides. Primary antibodies used were rabbit-derived anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (anti-TH, Sigma, 1:300), rabbit-derived anti-Iba-1 (Wako, 1:500), rat-derived anti-CD16/32 (BD, 1: 500) and rabbit-derived cleaved caspase-8 (Cell Signalling Technology, 1:150). Incubations and washes for all the antibodies were in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.4. All work was done at room temperature. Sections were first microwaved pre-treated in 10 mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 for 10min at 800W for antigen retrieval. Sections were washed and then treated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 20 min, washed again, and incubated in a solution containing TBS and 1% goat serum (Vector) for 60 min in a humid chamber. Slides were drained and further incubated with the primary antibody in TBS containing 1% serum and 0.25% Triton-X-100 for 24 h. Sections were then incubated for 2 h with either biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector, 1:200) for TH, Iba-1 and cleaved caspase-8 or immunostaining or goat anti-rat IgG for CD16/32. The secondary antibody was diluted in TBS containing 0.25% Triton-X-100, and its addition was preceded by three 10-min rinses in TBS. Sections were then incubated with ExtrAvidin®-Peroxidase solution (Sigma, 1:100). The peroxidase was visualized with a standard diaminobenzidine/hydrogen peroxide reaction for 5 min.

Immunofluorescence

Double-labelling were performed for Iba-1 and cleaved caspase-8, Iba1 and CD16/32 and CD16/32 and cleaved caspase-8. Two different Iba1 antibodies were used: mouse anti-Iba-1 (Millipore) to co-localize with cleaved caspase-8 and rabbit anti-Iba-1 (Wako) to co-localize with CD16/32. Sections were blocked with PBS containing 1% appropriate serums (Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour. The slides were washed three times in PBS, then incubated overnight at 4°C with the two primary antibodies to be tested diluted in PBS containing 1% appropriate serums and 0.25% Triton X-100. Sections were incubated with the following secondary antibodies: a) mouse anti-Iba1: horse anti-mouse conjugated to Texas Red (1:200; Vector Laboratories), b) rabbit anti-Iba1 and rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-8: horse anti-rabbit conjugated to Fluorescein (1:200; Vector Laboratories), c) rat anti-CD16/32: chicken anti-rat conjugated to AlexaFluor 594 (1:200, Invitrogen). Incubation with secondary antibodies were for 2 hours at room temperature in the dark. Their addition was preceded by three 10-minute rinses in PBS. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst dye (1 μg/ml; Molecular Probes/Invitrogen). Fluorescence images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 7 DUO confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany) and processed using the associated software package (ZEN 2010; Carl Zeiss Microscopy).

Immunohistochemistry data analysis

For counting the cell density of Iba1 and CD16/32 in the ventral mesencephalon in response to intranigral LPS injection, a systematic sampling of the area occupied by the immunolabelled positive cells in each section was made from a random starting point with a grid adjusted to count five fields per section. Analysis were made in a bounded region of the SN with a length of 300 microns in the anterior-posterior axis centred at the point of injection. In each case, five sections per animal were used, with random starting point and systematically distributed through the anterior-posterior axis of the analyzed region. An unbiased counting frame of known area (40 × 25 μm = 1000 μm2) was superimposed on the tissue section image under a 100X oil immersion objective. The different types of Iba1-positive cells (displaying different shapes depending on their activation state) were counted as a whole and expressed as cells per mm2. In MPTP-treated animals, stereological analysis was performed to calculate both the number of TH-labelled dopaminergic neurons in SN and the number of Iba1- and CD16/32-labelled microglia in substantia nigra and striatum. Stereological analysis were estimated using a fractionator sampling design [55]. Counts were made at regular predetermined intervals (x = 150 μm and y = 200 μm) within each section. An unbiased counting frame of known area (40 × 25 μm = 1000 μm2) was superimposed on the tissue section image under a 100× oil immersion objective. Therefore, the area sampling fraction is 1000/(150 × 200) = 0.033. The entire z-dimension of each section was sampled; hence, the section thickness sampling fraction was 1. In all animals, 25-μm sections, each 125 μm apart, were analysed; thus, the fraction of sections sampled was 25/125 = 0.20. The number of cells in the analyzed region was estimated by multiplying the number of neurons counted within the sample regions by the reciprocals of the area sampling fraction and the fraction of section sampled. TH immunohistochemistry in the striatum of mice intoxicated with MPTP was quantified using a computer-assisted software (analySIS). To carry out the quantification, five striatal sections from each condition, and processed under identical experimental conditions, were scanned at high resolution. The striatal region was delineated and its optical density measured based upon a calibrated grey scale.

Real time RT-PCR

The SN was dissected from each mouse 6 h after the injection of vehicle or LPS, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was extracted from the SN using RNeasy® kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using QuantiTect® reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) in 20 μl reaction volume as described by the manufacturer. Real-time PCR was performed with iQ™SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), 0.4 μM primers and 1 μl cDNA. Controls were carried out without cDNA. Amplification was run in a Mastercycler® ep realplex (Eppendorf) thermal cycler at 94 °C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s, followed by a final elongation step at 72°C for 7 min. Following amplification, a melting curve analysis was performed by heating the reactions from 65 to 95°C in 1°C intervals while monitoring fluorescence. Analysis confirmed a single PCR product at the predicted melting temperature. β-actin served as reference gene and was used for samples normalization. Primer sequences for iNOS, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β and β-actin are shown in Table 1. The cycle at which each sample crossed a fluorescence threshold (Ct) was determined, and the triplicate values for each cDNA were averaged. Analyses of real-time PCR were done using a comparative Ct method integrated in a Bio-Rad System Software.

Table 1. Primers for RT-PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase-8 | 5′-GGAAGATGACTTGAGCCTGC-3′ | 5′-GCTCTTGTTGACCTGGTCAC-3′ |

| Lysozyme 2 | 5′-GACCAAAGCACTGACTATGG-3′ | 5′-GATCCCACAGGCATTCACAG-3′ |

| NOS2 | 5′-GTGGTGACAAGCACATTTGG-3′ | 5′-AAGGCCA AACACAGCATACC-3′ |

| TNF | 5′-CTGAGGTCAATCTGCCCAAGTAC-3′ | 5′-CTTCACAGAGCAATGACTCCAAAG-3′ |

| IL1B | 5′-GCTGCTTCCAAACCTTTGAC-3′ | 5′-TTCTCCACAGC CACAATGAG-3′ |

| IL6 | 5′-GACCAAGACCATCCAATTC-3′ | 5′-GGCATAACGCACTAGGTTTG-3′ |

| ACTB | 5′-TTGCTGACAGGATGCAGAAG-3′ | 5′-TGATCCACATCTGCTGGAAG-3′ |

Statistical analysis

A minimum of five animals per experimental condition was analyzed. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Most analysis were evaluated byANOVA followed by the LSD test for post hoc multiple range comparisons. Striatal TH density was evaluated by a t-test using sidak-bonferroni test. Alphas value was set at 0.05. The Statgraphic Plus 3.0 software was used.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, the Parkinson Foundation in Sweden, the Swedish Brain Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (SAF2012–39029) and the Junta of Andalucía (P10-CTS-6494).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hirsch EC, Hunot S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease: a target for neuroprotection? The LancetNeurology. 2009;8:382–397. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tansey MG, McCoy MK, Frank-Cannon TC. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms in Parkinson's disease: potential environmental triggers, pathways, and targets for early therapeutic intervention. Experimental neurology. 2007;208:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu X, Leak RK, Shi Y, Suenaga J, Gao Y, Zheng P, Chen J. Microglial and macrophage polarization-new prospects for brain repair. Nature reviews Neurology. 2015;11:56–64. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varnum MM, Ikezu T. The classification of microglial activation phenotypes on neurodegeneration and regeneration in Alzheimer's disease brain. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 2012;60:251–266. doi: 10.1007/s00005-012-0181-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klegeris A, McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Therapeutic approaches to inflammation in neurodegenerative disease. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2007;20:351–357. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3280adc943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGeer PL, Itagaki S, McGeer EG. Expression of the histocompatibility glycoprotein HLA-DR in neurological disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 1988;76:550–557. doi: 10.1007/BF00689592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Glial reactions in Parkinson's disease. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2008;23:474–483. doi: 10.1002/mds.21751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Zhang SM, Hernan MA, Schwarzschild MA, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Ascherio A. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of Parkinson disease. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60:1059–1064. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esposito E, Di Matteo V, Benigno A, Pierucci M, Crescimanno G, Di Giovanni G. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Parkinson's disease. Experimental Neurology. 2007;205:295–312. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I, Wronska A, Kohutnicka M, Czlonkowski A, Czlonkowska A. The inflammatory reaction following 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3, 6-tetrahydropyridine intoxication in mouse. Experimental Neurology. 1999;156:50–61. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberatore GT, Jackson-Lewis V, Vukosavic S, Mandir AS, Vila M, McAuliffe WG, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Przedborski S. Inducible nitric oxide synthase stimulates dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the MPTP model of Parkinson disease. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:1403–1409. doi: 10.1038/70978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Przedborski S, Jackson-Lewis V, Naini AB, Jakowec M, Petzinger G, Miller R, Akram M. The parkinsonian toxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP): a technical review of its utility and safety. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;76:1265–1274. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holst O, Ulmer AJ, Brade H, Flad HD, Rietschel ET. Biochemistry and cell biology of bacterial endotoxins. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 1996;16:83–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kielian TL, Blecha F. CD14 and other recognition molecules for lipopolysaccharide: a review. Immunopharmacology. 1995;29:187–205. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00003-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrera AJ, Castano A, Venero JL, Cano J, Machado A. The single intranigral injection of LPS as a new model for studying the selective effects of inflammatory reactions on dopaminergic system. Neurobiology of Disease. 2000;7:429–447. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castano A, Herrera AJ, Cano J, Machado A. Lipopolysaccharide intranigral injection induces inflammatory reaction and damage in nigrostriatal dopaminergic system. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;70:1584–1592. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WG, Mohney RP, Wilson B, Jeohn GH, Liu B, Hong JS. Regional difference in susceptibility to lipopolysaccharide-induced neurotoxicity in the rat brain: role of microglia. The Journal of neuroscience. 2000;20:6309–6316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06309.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph B, Ekedahl J, Lewensohn R, Marchetti P, Formstecher P, Zhivotovsky B. Defective caspase-3 relocalization in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Oncogene. 2001;20:2877–2888. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venero JL, Burguillos MA, Joseph B. Caspases playing in the field of neuroinflammation: old and new players. Developmental Neuroscience. 2012;35:88–101. doi: 10.1159/000346155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burguillos MA, Deierborg T, Kavanagh E, Persson A, Hajji N, Garcia-Quintanilla A, Cano J, Brundin P, Englund E, Venero JL, Joseph B. Caspase signalling controls microglia activation and neurotoxicity. Nature. 2011;472:319–324. doi: 10.1038/nature09788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldmann T, Wieghofer P, Muller PF, Wolf Y, Varol D, Yona S, Brendecke SM, Kierdorf K, Staszewski O, Datta M, Luedde T, Heikenwalder M, Jung S, et al. A new type of microglia gene targeting shows TAK1 to be pivotal in CNS autoimmune inflammation. Nature Neuroscience. 2013;16:1618–1626. doi: 10.1038/nn.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ros-Bernal F, Hunot S, Herrero MT, Parnadeau S, Corvol JC, Lu L, Alvarez-Fischer D, Carrillo-de Sauvage MA, Saurini F, Coussieu C, Kinugawa K, Prigent A, Hoglinger G, et al. Microglial glucocorticoid receptors play a pivotal role in regulating dopaminergic neurodegeneration in parkinsonism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:6632–6637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017820108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xing B, Bachstetter AD, Van Eldik LJ. Microglial p38alpha MAPK is critical for LPS-induced neuron degeneration, through a mechanism involving TNFalpha. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2011;6(84):1326–1384. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho IH, Hong J, Suh EC, Kim JH, Lee H, Lee JE, Lee S, Kim CH, Kim DW, Jo EK, Lee KE, Karin M, Lee SJ. Role of microglial IKKbeta in kainic acid-induced hippocampal neuronal cell death. Brain. 2008;131:3019–3033. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomas-Camardiel M, Rite I, Herrera AJ, de Pablos RM, Cano J, Machado A, Venero JL. Minocycline reduces the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory reaction, pero-xynitrite-mediated nitration of proteins, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, and damage in the nigral dopaminergic system. Neurobiology of Disease. 2004;16:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fricker M, Vilalta A, Tolkovsky AM, Brown GC. Caspase inhibitors protect neurons by enabling selective necroptosis of inflamed microglia. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:9145–9152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.427880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SJ, Li J. Caspase blockade induces RIP3-mediated programmed necrosis in Toll-like receptor-activated microglia. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4:e716. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaczmarek A, Vandenabeele P, Krysko DV. Necroptosis: the release of damage-associated molecular patterns and its physiological relevance. Immunity. 2013;38:209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB, Livingston-Rosanoff D, Daley-Bauer LP, Hakem R, Caspary T, Mocarski ES. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;471:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature09857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirai T, Uchida K, Nakajima H, Guerrero AR, Takeura N, Watanabe S, Sugita D, Yoshida A, Johnson WE, Baba H. The prevalence and phenotype of activated microglia/macrophages within the spinal cord of the hyperostotic mouse (twy/twy) changes in response to chronic progressive spinal cord compression: implications for human cervical compressive myelopathy. PloS one. 2013;8:e64528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu X, Li P, Guo Y, Wang H, Leak RK, Chen S, Gao Y, Chen J. Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2012;43:3063–3070. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.659656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:13435–13444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villaran RF, Espinosa-Oliva AM, Sarmiento M, De Pablos RM, Arguelles S, Delgado-Cortes MJ, Sobrino V, Van Rooijen N, Venero JL, Herrera AJ, Cano J, Machado A. Ulcerative colitis exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced damage to the nigral dopaminergic system: potential risk factor in Parkinson`s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;114:1687–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faucheux BA, Bonnet AM, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. Blood vessels change in the mesencephalon of patients with Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 1999;353:981–982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00641-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Issidorides MR. Neuronal vascular relationships in the zona compacta of normal and parkinsonian substantia nigra. Brain Research. 1971;25:289–299. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meredith GE, Rademacher DJ. MPTP mouse models of Parkinson's disease: an update. Journal of Parkinson's Disease. 2011;1:19–33. doi: 10.3233/JPD-2011-11023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokoyama H, Kuroiwa H, Yano R, Araki T. Targeting reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species and inflammation in MPTP neurotoxicity and Parkinson's disease. Neurological Sciences. 2008;29:293–301. doi: 10.1007/s10072-008-0986-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Depboylu C, Stricker S, Ghobril JP, Oertel WH, Priller J, Hoglinger GU. Brain-resident microglia predominate over infiltrating myeloid cells in activation, phagocytosis and interaction with T-lymphocytes in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson disease. Experimental Neurology. 2012;238:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varfolomeev EE, Schuchmann M, Luria V, Chiannilkulchai N, Beckmann JS, Mett IL, Rebrikov D, Brodianski VM, Kemper OC, Kollet O, Lapidot T, Soffer D, Sobe T, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse Caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1, and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity. 1998;9:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, McCormick LL, Fitzgerald P, Pop C, Hakem R, Salvesen GS, Green DR. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature. 2011;471:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature09852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maelfait J, Beyaert R. Non-apoptotic functions of caspase-8. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008;76:1365–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oberst A, Green DR. It cuts both ways: reconciling the dual roles of caspase 8 in cell death and survival. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2011;12:757–763. doi: 10.1038/nrm3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou W, Yuan J. Necroptosis in health and diseases. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2014;35C:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Dri P, Gordon S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1990;39:151–170. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuda CM, Misharin AV, Gierut AK, Saber R, Haines GK, 3rd, Hutcheson J, Hedrick SM, Mohan C, Budinger GS, Stehlik C, Perlman H. Caspase-8 acts as a molecular rheostat to limit RIPK1- and MyD88-mediated dendritic cell activation. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2014;192:5548–5560. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gurung P, Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Vande Walle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Green DR, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. FADD and caspase-8 mediate priming and activation of the canonical and noncanonical Nlrp3 inflammasomes. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2014;192:1835–1846. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang TB, Yang SH, Toth B, Kovalenko A, Wallach D. Caspase-8 blocks kinase RIPK3-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunity. 2013;38:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maelfait J, Vercammen E, Janssens S, Schotte P, Haegman M, Magez S, Beyaert R. Stimulation of Toll-like receptor 3 and 4 induces interleukin-1beta maturation by caspase-8. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205:1967–1973. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arimoto T, Bing G. Up-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in the substantia nigra by lipopolysaccharide causes microglial activation and neurodegeneration. Neurobiology of Disease. 2003;12:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(02)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hunot S, Boissiere F, Faucheux B, Brugg B, Mouatt-Prigent A, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. Nitric oxide synthase and neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. 1996;72:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00578-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le W, Rowe D, Xie W, Ortiz I, He Y, Appel SH. Microglial activation and dopaminergic cell injury: an in vitro model relevant to Parkinson's disease. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21:8447–8455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08447.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hald A, Lotharius J. Oxidative stress and inflammation in Parkinson's disease: is there a causal link? Experimental Neurology. 2005;193:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu DC, Jackson-Lewis V, Vila M, Tieu K, Teismann P, Vadseth C, Choi DK, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S. Blockade of microglial activation is neuroprotective in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson disease. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:1763–1771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01763.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ch'en IL, Tsau JS, Molkentin JD, Komatsu M, Hedrick SM. Mechanisms of necroptosis in T cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2011;208:633–641. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gundersen HJ, Bagger P, Bendtsen TF, Evans SM, Korbo L, Marcussen N, Moller A, Nielsen K, Nyengaard JR, Pakkenberg B. The new stereological tools: disector, fractionator, nucleator and point sampled intercepts and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS: Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica, et Immunologica Scandinavica. 1988;96:857–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]