Abstract

This review presents and applies fundamental mass transport theory describing the diffusion and convection driven mass transport of drugs to the vaginal environment. It considers sources of variability in the predictions of the models. It illustrates use of model predictions of microbicide drug concentration distribution (pharmacokinetics) to gain insights about drug effectiveness in preventing HIV infection (pharmacodynamics). The modeling compares vaginal drug distributions after different gel dosage regimens, and it evaluates consequences of changes in gel viscosity due to aging. It compares vaginal mucosal concentration distributions of drugs delivered by gels vs. intravaginal rings. Finally, the modeling approach is used to compare vaginal drug distributions across species with differing vaginal dimensions. Deterministic models of drug mass transport into and throughout the vaginal environment can provide critical insights about the mechanisms and determinants of such transport. This knowledge, and the methodology that obtains it, can be applied and translated to multiple applications, involving the scientific underpinnings of vaginal drug distribution and the performance evaluation and design of products, and their dosage regimens, that achieve it.

Keywords: vagina, microbicides, HIV, modeling, gel, ring, diffusion, convection, mucosa

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

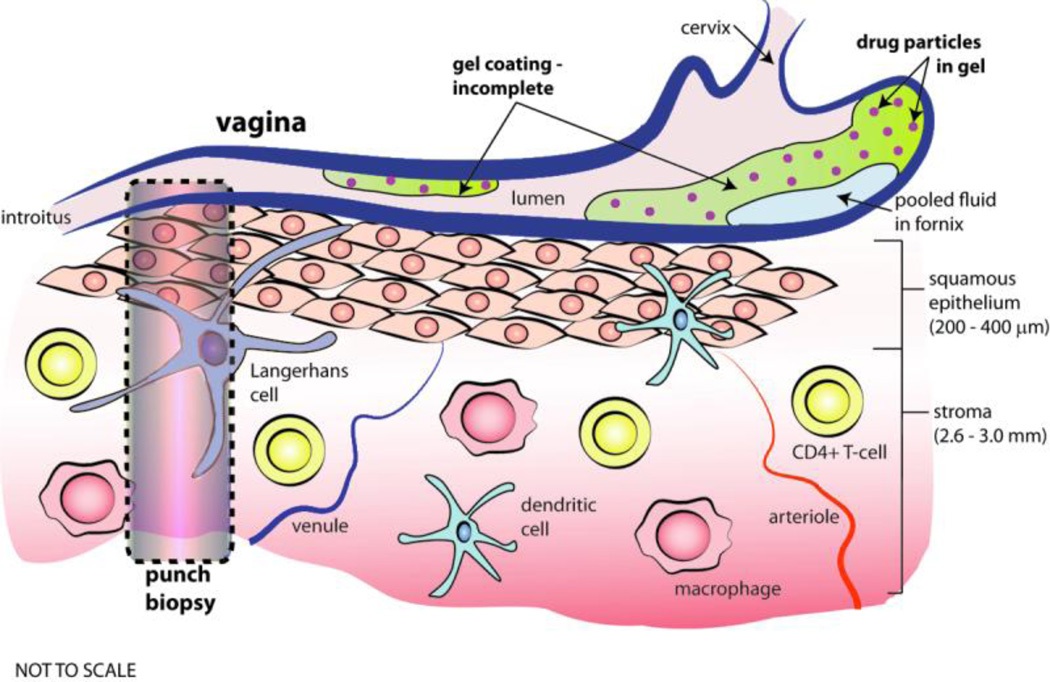

The human vagina is a fibromuscular tract that connects the vulva to the cervix and uterus and thence the organs of the upper reproductive tract [1]. It is about 10 – 15 cm long, and its lumen is largely collapsed, resulting in a relatively flat cross section (width about 2 – 3 cm), except at the innermost region, the fornix. Its net surface area is about 80 – 110 cm2. Its mucosa consists of two layers: a stratified squamous epithelium, that varies in thickness during the menstrual cycle from about 200 – 400 µm; and a lamina propria (connective tissue, also termed the stroma) that is about 2.5 – 3 mm thick. The stroma is about 10% vasculature by volume (there is no vasculature in the epithelium), and it contains host cells that HIV virions can infect (e.g. CD4+ T cells and macrophages). Below the stroma are muscular and outer connective tissue layers. The vagina does not secrete fluid per se. Mucus from the cervix leaks down through the external cervical os into the floor of the fornix, primarily at midcycle. It may then be distributed in a thin layer over the epithelial surfaces of the vaginal canal, although details of this are not well understood. Sexual stimulation increases the pressure in the vasculature in the stroma, resulting in transudation of fluid through the epithelium to its surface (“lubrication”) [2]. We have only approximate knowledge of the quantitative amount and distribution of ambient fluid in the vagina [3]. It is maximal under conditions of maximum estrogen presence in the vaginal environment (e.g. at the midportion of the menstrual cycle) and minimal in conditions of low estrogen and high progesterone (viz. in the luteal phase of the cycle, and post menopause; here the epithelium in thinnest). The maximum volume of ambient vaginal fluid is believed to about around 1 – 2 mL.

Delivery of drugs via the vagina has been implemented for many years, for many purposes [4]. Commercial and in-development vaginal products now introduce a variety of drugs intended for systemic delivery (e.g. contraceptive hormones and prostaglandins [5] and topical delivery (e.g. spermicides, agents against urinary tract infections and candida infections, anti-bacterial vaginosis medications, labor inducing agents, etc. [6–10]). At present there is much activity directed at development of products that deliver drugs – termed microbicides – which act topically in the vaginal environment to inhibit infection by sexually transmitted HIV and/or other pathogens, e.g. human papilloma virus (HPV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) [11–13]. Complementary approaches have focused on delivering antimicrobial antibodies. This application of drug delivery was pioneered by Saltzman and colleagues in the mid 1990s [14, 15]. Drug delivery via the vagina is currently implemented or being developed via administration of a range of dosage forms to the vaginal canal: monolithic solid materials (e.g. intravaginal rings, IVRs) and soft, semi-solid materials (e.g. gels, creams, suppositories, films, non-woven porous textile materials, dissolving tablets, and fiber-woven meshes) [16–18]. A number of review articles have already been written about vaginal drug delivery [6–10]. For the most part, these have focused upon the compositions and properties of the various delivery systems, with reference to the delivered drugs and vaginal physiology and anatomy. There has been relatively little attention to the use and potential impact of modeling of the drug delivery performance per se of the various products. To be sure, the benefits of modeling vary, depending upon the site and mechanism of action of the delivered drug. For example, therapeutic delivery of antifungal compounds by creams, gels or suppositories against candida infections essentially involves coating, if not filling, the vagina canal with drug that will subsequently mix with ambient vaginal fluids and complete the transvaginal distribution process over time. Maximizing retention of drug on the mucosal surfaces, e.g. via mucoadhesive agents, is important here. However, the time constraint on minimizing the interval before onset of therapeutic action is not acute. In contrast, prophylactic delivery of topically acting anti-HIV microbicide drugs (to vaginal fluids and/or mucosal tissues) is acutely time and space dependent. In a sense, it is a race against the arrival of infectious virions from semen to sites, distributed throughout the length of the mucosa, that are vulnerable to infection. The goal of drug delivery for prophylaxis is to rapidly achieve prophylactic concentrations of drugs at target sites, and to achieve and maintain a high level of prophylactic action as long as possible. Here, the value of modeling can be substantial, viz. it can predict the time interval after product application at which prophylactic concentrations of drug(s) are achieved and sustained, at the level of such prophylaxis, at target sites. More fundamentally, it can help guide the rational design and evaluation of candidate products. This was appreciated by Saltzman and colleagues in their studies of delivery of anti-HSV IgG antibodies by EVA disks [15]. They created a pharmacokinetic compartmental model of antibody concentration (volume averaged) in the vagina by diffusion out from a circular disk, and they applied the model to experimental data in the mouse. In follow up, Saltzman presented two additional model analyses: bolus delivery in the presence of vaginal fluid flow; and diffusion controlled drug release from an intravaginal ring (see section below on IVR modeling) [19, 20].

Since those pioneering analyses (over a decade ago), there has been relatively little modeling of microbicide drug delivery to the vaginal (and rectal) environments. This has fundamentally limited our ability to understand the determinants of that performance and to incorporate such knowledge into objective product design and dosing schemas. The review article here is intended to help fill this gap. Our focus is upon drug delivery systems that introduce active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) that act topically within the vaginal environment (fluids and tissues), with particular emphasis upon microbicides. Quantitative illustrations of applications of modeling are presented for a leading microbicide drug Tenofovir, although the general methodological approach extends more broadly to the spectrum of microbicide drugs being evaluated. Recently, some aspects of such modeling were reviewed [18].

In this article, we present a summary of the nature of deterministic modeling of vaginal drug delivery and distribution, achieved by multiple dosage forms. We then describe several specific applications of modeling that can have value to pharmacological and biological understanding of vaginal product functionality: (1) translating modeling of drug distribution per se (pharmacokinetics) to information about drug functionality (pharmacodynamics); (2) comparing effects of different gel dosage regimens; (3) interpreting consequences of gel aging during storage; (4) comparing modeling results for different dosage forms, viz. gels vs. intravaginal rings; and (5) planning and interpreting studies across multiple species, comparing humans to smaller animals.

The approach reviewed here is complementary to, but different in many ways from traditional empirical PBPK modeling, which has been applied in the context of vaginal drug delivery [21–24]. Both approaches implement conservation of drug mass principles, but deterministic modeling embodies additional biophysical principles that govern how drugs migrate within and between compartments. Our descriptions of how the modeling works necessarily involve technical language and use of equations to characterize cause and effect in the examples presented. We hope the information and illustrations of modeling here will be helpful to the broader field of vaginal drug delivery, and be useful in connecting scientific understanding and research to product development and dosing specification, e.g. in the current microbicide pipeline.

2. Building deterministic models

Distribution of a drug throughout the vaginal environment is a mass transport process in which several types of active forces (e.g. squeezing by the walls of the canal, pressure gradients imposed on the canal, surface tension) interact with passive diffusion to drive drug transport. The forces can induce flow of fluids in the canal and thus transport derives from both convective and diffusive processes. Deterministic modeling applies conservation principles of momentum, mass and energy, coupled to constitutive relationships (e.g. Fick’s Law of diffusion; rheological constitutive equations relating frictional stresses to fluid strains and strain rates) [18, 25]. Topical vaginal drug delivery, and microbicide prophylactic functionality in particular, are processes in which spatial distributions of drugs within compartments – both the vehicle and target fluids and tissues – drive transport and can be highly non-uniform. In target tissues and fluids, this can result in non-uniform local prophylactic ability against migrating pathogens, the concentration distributions of which are also non-uniform.

During the past decade, most implementations of deterministic modeling of vaginal drug distribution focused upon flow of gels and their distribution along the canal, not drug transport per se [18]. The logic was that the surface area of gel-mucosal contact is a primary determinant of drug transport into the mucosa. Further, excessive coating, leading to leakage from the introitus, was discouraging to user willingness to apply a product. Thus, ‘good’ coating was ‘good’ for local vaginal drug distribution and also user acceptability. A succession of non-Newtonian fluid mechanics-based coating models, with increasing biophysical comprehensiveness, was created [26–32]. The modeling related details of coating to properties (and therefore composition) of a gel, its volume, and details of the host environment (e.g. squeezing forces by vaginal walls, anatomy of the vaginal canal). Consequently, predictions of one of the earlier models of gel spreading were incorporated into design schema for vaginal microbicide gels [33–35]. This latter approach did not directly compute drug transport. Rather, it applied an algorithm based upon semi-empirical assumptions about how gel coating area and thickness govern drug release to the vaginal mucosal epithelial surface.

More recently, models were developed of vaginal microbicide drug transport per se, as released by intravaginal rings [36] and gels [37]. The earlier ring model incorporated drug convection by flowing vaginal fluid as well as diffusion, to compute the flux of the microbicide Dapivirine to vaginal surfaces. It did not address drug transport into and through the epithelial and stromal layers of the vaginal mucosa, within which Dapivirine is believed to act against HIV. More recently, a compartmental model was developed for drug transport from a gel layer into the vaginal mucosal epithelial and stromal layers (with clearance to the blood stream in the latter) [37]. Complete, uniform coating of the vaginal epithelial surface was assumed, so that drug transport was entirely driven by diffusion. Predictions for the microbicide drug Tenofovir (TFV) gave reasonable agreement with data from two human PK studies of vaginal gel delivery of this drug (see below) [24, 38]. Importantly, model results characterized the non-uniform spatial TFV concentration distributions in epithelium and stroma, and how these limited interpretation of concentrations measured experimentally in a vaginal biopsy – which are volume averages over an uncontrolled (and unmeasured) thickness of tissue. Still more recently, we began to combine time-dependent gel spreading with drug diffusion processes in a full convection-diffusion compartmental model of drug transport into vaginal epithelium and stroma [39–41]. In so doing, we included phosphorylation of Tenofovir to Tenofovir Diphosphate (TFV-DP) in cells. TFV-DP is the active anti-HIV product of TFV, acting as a reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Thus, TFV-DP concentrations in HIV-infectible host cells (viz. in vaginal stoma) are a more direct indicator of drug product effectiveness than concentrations of TFV, although the two concentrations are related. An important distinction in interpreting TFV and TFV-DP concentrations is that there is a very slow clearance rate of TFV-DP from cells, in contrast to the much more rapid clearance of TFV. This is manifest in computations from our model.

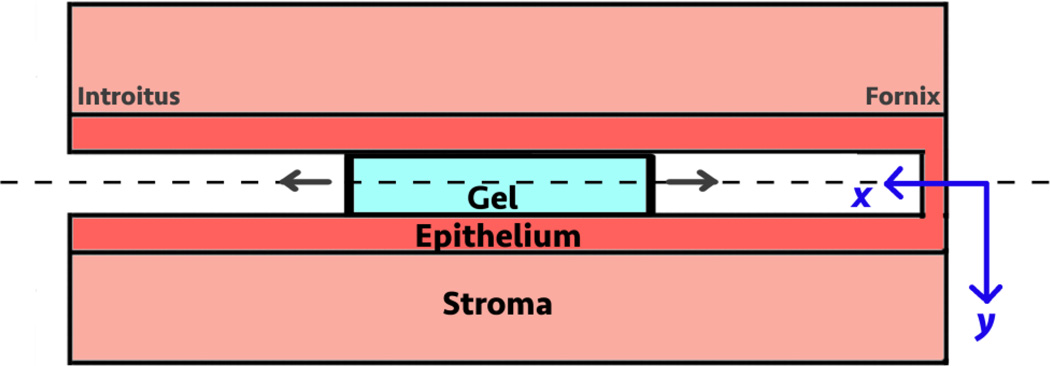

We illustrate this model by applying it to the 1% TFV clinical gel used in the three trials noted above. We have measured detailed rheological properties of this gel, as well as transport parameters (diffusion and partition coefficients) for Tenofovir in this gel and in fresh porcine vaginal mucosal tissue [42]. Figure 2 is a schematic of the configuration and (x,y) coordinate system in the model. The problem is symmetrical about y = 0, and is solved in the half plane for y > 0.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing of the gel spreading and drug mass transport problem. Gel flow and drug mass transport are symmetrical in the half planes about y = 0. The problem is therefore solved for y > 0.

The following is the system of mass conservation equations in the model.

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

| (1c) |

| (1d) |

| (1e) |

Here concentrations are defined as per unit volume of the matrix (viz. the 4 compartments). Equation (1a) if for TFV concentration CG in the gel compartment, where DE is the diffusion coefficient in the epithelium, and CE is TFV concentration in the epithelium; w is the width of the canal, L is the distance from the center to the edge of the gel, and VG is the gel volume. The integral gives total mass of drug leaving the gel to the epithelium. TFV concentration in gel is also reduced due to imbibing of ambient vaginal fluid, and this is modeled as a first order process with rate constant kD [37]. TFV transport in epithelium (equation (1b)) is a 2-dimensional unsteady diffusion process; CE is TFV concentration and DE is the diffusion coefficient. The last two terms of the equation are the creation and elimination rate for tenofovir diphosphate, TFV-DP, where kon is the formation rate of TFV-DP, koff is the elimination of TFV-DP, ϕE is the volume fraction of cells in the epithelium, and r is the fraction of TFV converted to TFV-DP within the cells. TFV transport in stroma (equation (1c)) is also a two-dimensional unsteady diffusion process with a first order loss term for uptake into the vasculature with rate constant kB [37]; Cs is TFV concentration, DS is TFV diffusion coefficient; the TFV-DP production mechanism is taken to be similar to the one in epithelium except with a different host cell volume fraction ϕS. The blood vessels are distributed relatively uniformly throughout the stromal layer. In the blood compartment (equation (1d)), the mass balance of concentration of TFV, CB is governed by the input from the stroma divided by VB (the volume of the blood compartment) and loss due to metabolism by the body (with first order rate constant kL, typically given as a volumetric value. The time rate of change for TFV-DP (equation (1e)) has two components on the right hand side of the equation. The first is the rate of formation kon multiplied by the difference between the current level of TFV-DP and the saturation level based on the local tenofovir concentration CTFV in the epithelium or stroma, the proportion of host cells ϕ, and the fraction r of TFV that can be converted to TFV-DP. This term is inside Macaulay brackets { } (defined such that the expression inside the brackets is zero when it is computed to be negative; the TFV-DP formation rate must be strictly positive or zero). The second component is the rate of elimination, or the conversion from TFV-DP to TFV, governed by the rate constant koff. The boundary and initial conditions are as follows.

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

| (2c) |

| (2d) |

| (2e) |

| (2f) |

| (2g) |

| (2h) |

| (2i) |

| (2j) |

| (2k) |

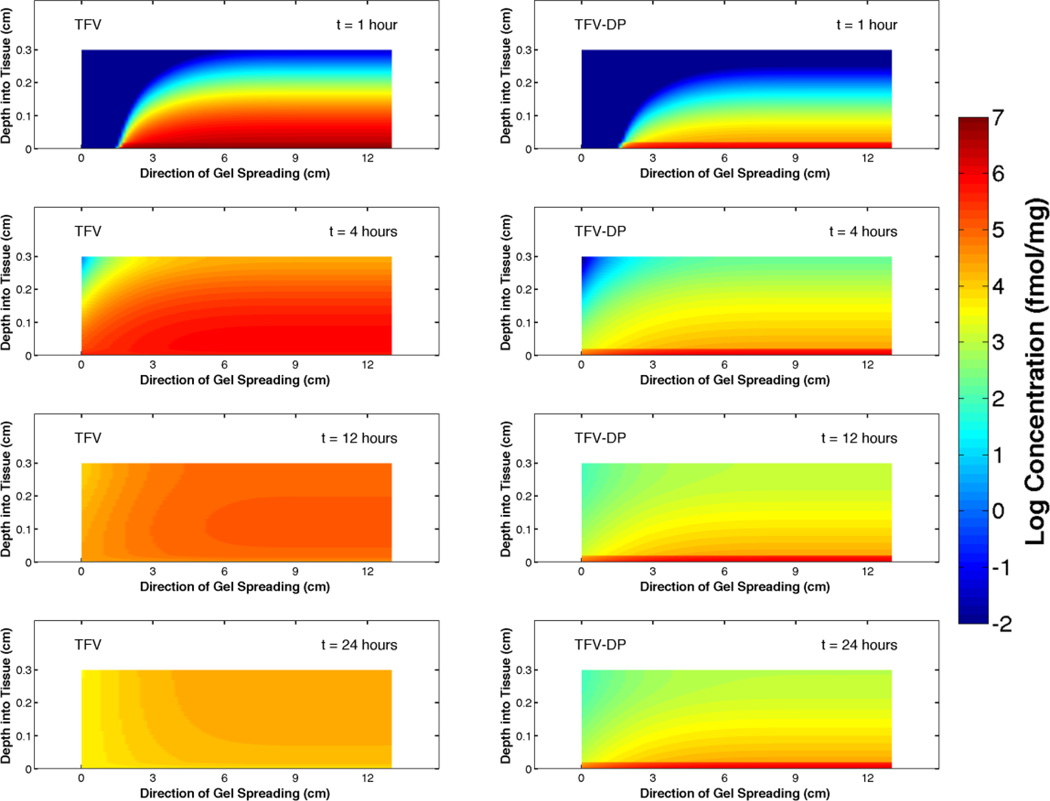

Values of parameters in the computations here were taken from our earlier analysis of TFV transport [37] now modified to include experimentally determined diffusion coefficients for TFV [42]. The equations were solved numerically using Matlab software (MathWorks, Inc, Natick, MA). The following are heat map plots of the concentration distributions of TFV and TFV-DP at 1, 4, 12 and 24 hours after insertion of 4 mL of gel to the fornix of a vaginal canal of average anatomical dimensions (13 cm long and 3.35 cm wide, [43]). Thicknesses of the epithelium and stroma are 200 µm and 2.8 mm, respectively.

Note that concentration of TFV longitudinally along the canal maps closely with the leading edge of the gel as it spreads. Peak concentrations in tissue diminish over time, as gel spreads along the canal and drug diffuses through the tissue and is cleared to the vasculature in the stroma.

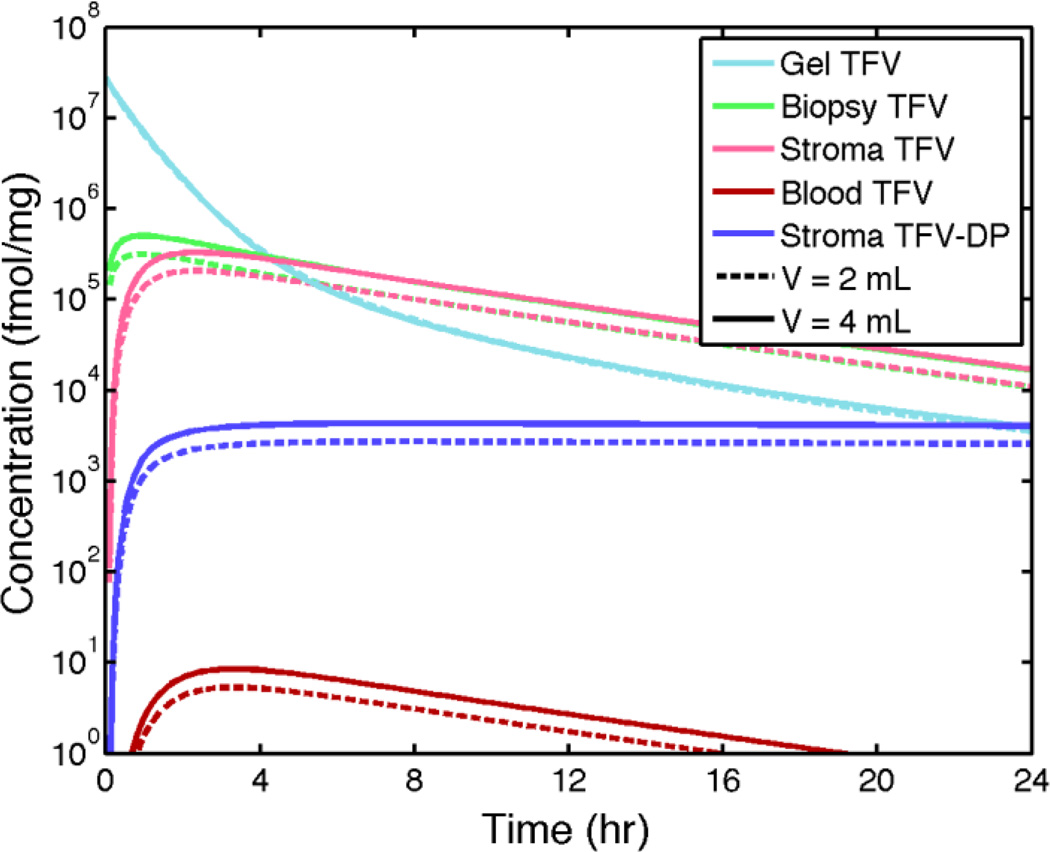

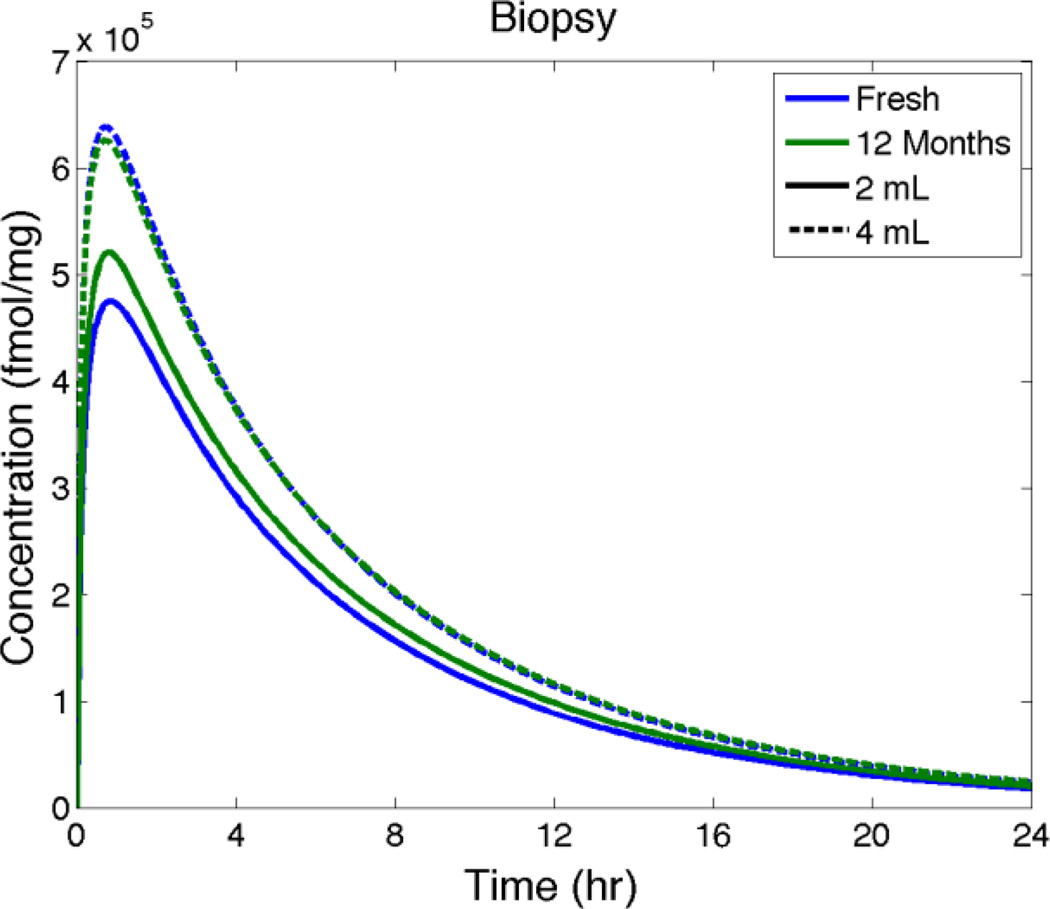

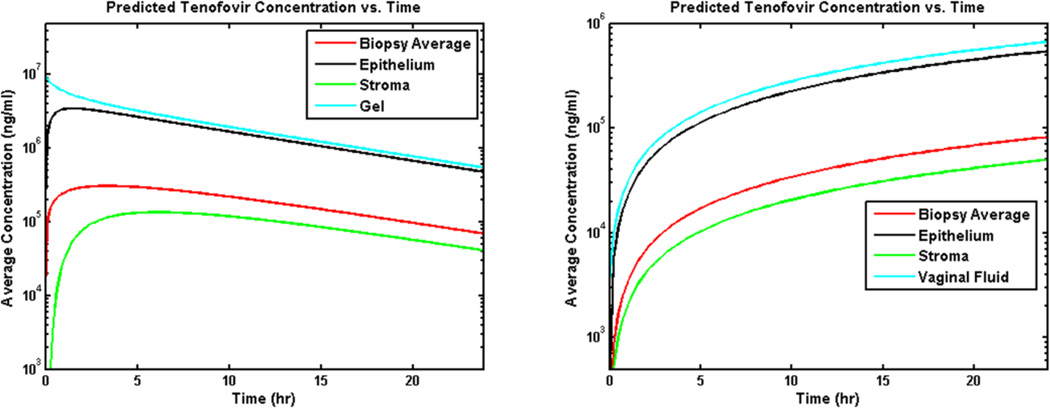

Figure 4 shows volume-averaged concentrations of TFV and TFV-DP vs. time for several compartments and also a simulated biopsy (epithelium + stroma). Contrasting values of gel volume (for fixed TFV loading at 1%) provide an indication of the relatively small effect of reducing gel volume on the average concentrations.

Figure 4.

Compartment-averaged concentrations vs. time of TFV and TFV-DP from model predictions for the 1% TFV clinical gel inserted to the fornix in a human vaginal canal of average size (cf. Figure 3). Two clinically relevant gel volumes, 2 mL and 4 mL, are considered.

Results in Figure 4 also clearly show the effect on maintaining stromal concentration of the long half life of TFV-DP in cells. These results show that concentrations of TFV measured in biopsies (simulated by the model) are a good estimate of TFV concentrations in stroma. They initially overestimate TFV concentrations in stroma (where its phosphorylate TFV-DP is largely bioactive against HIV) but that this overestimation ceases after about 2 hours. In contrast, TFV concentrations in epithelium are as much as one log higher than those in a biopsy for the first 4 hours after gel insertion (data not shown). These results also indicate that there are relatively small differences in the compartmental drug concentrations for the 2 mL vs. 4 mL gel volumes.

3. The importance of model parameters and the sources of variability

As sound as the foundations of models can be, their predictions are critically dependent upon the fidelity of the values of parameters input to them. Hence the old adage, “garbage in – garbage out.” Deterministic vaginal drug distribution modeling, as all PK modeling, embodies a great many parameters that characterize properties of the drugs, their vehicles, their dosage regimens, the host environments, etc. In empirical PK modeling, drug mass exchange between compartments is generally characterized as a first order rate process in concentrations, and values of the rate constants are based upon empirical data, often extrapolated across multiple studies from studies with different designs. In deterministic modeling, values of many of the key parameters can be experimentally measured or mathematically predicted objectively. Examples of the former are rheological properties of vaginal gel formulations and diffusion and partition coefficients of drugs in gel, epithelium and stroma [44, 45]. This article does not address the methods and challenges of measuring parameters for models. But it is important to appreciate that there is uncertainty in the values of parameters in models and that this contributes to the overall uncertainty in the predictions of those models, as well as inaccuracies in the models per se. In reference, experimental data on drug concentrations in vaginal microbicide PK and efficacy studies are beset with variability, the origins of which are not fully understood. Empirical population based PK modeling for microbicide gels and intravaginal rings has begun analyses which quantify the uncertainty in clinical trial data [22, 23]. One use of such modeling is to define ranges of expected values of drug concentrations sampled at specified times after product insertion. This could be used to assess whether or not the product was applied as instructed and reported by users [23], and could also guide selection of best times after product insertion to obtain samples in studies.

As a simple example of the use of deterministic modeling in addressing variability in human PK data, we have considered perturbations in several parameters that result from natural biological variability in vaginal gel users: the dimensions of the vaginal canal, the thickness of the epithelial layer, the volume of gel inserted (vs. the nominal amount contained in an applicator), the location along the vaginal canal at which a gel bolus is released from its applicator; the volume of vaginal fluid as manifest in the rate of gel dilution; and the exact interval between gel insertion (as reported by a user) and the time at which drug concentration is measured (e.g. the time at which a biopsy is taken, for subsequent drug concentration measurement). We considered upper and lower bounds for each parameter, which occurred independently of variations in all other parameters: (1) vaginal size (canal length L and width W) was taken as large or small based on human morphometric data [43], L = 15 cm, W = 3.5 cm or. L = 12 cm, W = 3 cm); (2) epithelial thickness was 200 µm or 300 µm [46]; (3) gel volume was 4 mL or 3 mL (based on our unpublished data for in vivo measurements in women in applying gel in a 4 mL applicator; (4) site of gel insertion was to the inner fornix vs. midway along the vaginal canal; (5) vaginal fluid dilution rate of gel was increased by a factor of two (reflecting more ambient fluid in contact with gel; our reference condition was production of 3 mL per day); and (6) the interval between gel insertion and time that concentration was computed was in error by −30 minutes. The simulation is not a full statistical analysis of how the distribution of uncertainty in each parameter impacted model predictions. Rather, we considered the 64 separate combinations of parameter values based on using the upper and lower bounds of each. We computed as endpoints the Cmax values for the concentrations of Tenofovir in a biopsy, and the concentrations of Tenofovir Diphosphate in stroma at 4 hours after gel application (since the TFV-DP curve vs. time does not exhibit a distinct maximum within 24 hours of gel application). Using the sets of 64 values for each of these endpoints, we then built a first order log-linear statistical model, incorporating all 6 parameters, to predict each endpoint (Equation 3).

| (3) |

| (4) |

Here, C is the endpoint concentration, the xi are the parameters (i = 1 – 6), and the bi are coefficients determined from the fitting of the model. The value of bo is the computed concentration when all parameters are at baseline (xi = 0). When any parameter is not at baseline, then xi = 1 and the corresponding bi has an independent multiplicative effect on the value of C. Equation (3) is log linear, and by taking the natural log on both sides, each parameter xi is linearized in equation (4). A linear regression can then be performed on the 64 data points each with a corresponding set of parameters indicating whether each parameter is at its baseline or comparison value. R2 values for predictions of the deterministic simulation endpoints by their statistical models were 0.972 and 0.990, respectively, for TFV in a biopsy and TFV-DP in stroma. Results of application of this model to the simulated experimental measurements of TFV and TFV-DP concentrations are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Effects of independent differences in values of the 6 parameters in the log-linear model on their coefficients in the model. The reference baseline value for each coefficient is 1 and the numbers in the table are the modified values for each coefficient when the parameter is changed from its value in the left column to its value in the right column. Results for each parameter are presented as its computed value (95% confidence interval).

| Baseline | Comparison | Biopsy TFV (fmol/mg) | Stromal TFV-DP (fmol/mg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Value | - | - | 7.84e5(7.58e5, 8.11e5) | 6.80e3(6.63e3, 6.97e3) |

| Vaginal Size | small | large | 0.77(0.75, 0.79) | 0.77(0.76, 0.78) |

| Gel Volume | 3 mL | 4 mL | 1.18(1.15, 1.21) | 1.17(1.15, 1.19) |

| Place of Insertion | middle | fornix | 0.86(0.84, 0.88) | 0.85(0.84, 0.87) |

| Epithelial Thickness | 200 µm | 300 µm | 0.92(0.90, 0.95) | 0.66(0.65, 0.68) |

| Gel Dilution | half | standard | 0.65(0.64, 0.67) | 0.65(0.64, 0.67) |

| Time | t-30 min | t | 1.09(1.06, 1.11) | 1.04(1.02, 1.06) |

Results in Table 1 show that gel dilution and vaginal size are the parameters most influencing TFV concentrations in a simulated biopsy. That is, larger vaginal size reduces concentration by 23%, and the increase in dilution causes a 35% decrease. For TFV-DP concentrations in stroma, the thickness of the stroma is as important as gel dilution, a 50% increase in thickness reducing concentration by 34%. In follow up, second order log linear models can be created to account more fully for interactions between pairs of parameters. Results (not shown) confirm the primary findings in Table 1 regarding the salient parameters that govern concentrations.

Predictions such as these can provide insights into salient factors that impact PK and PD. For example, if vaginal size correlates with body mass index and/or parity/gravidity (both of which can be measured in clinical trial participants) then participants could be stratified using both those measurements. Analogously, the presence of vaginal fluid and epithelial thickness may correlate with cycle phase (fluid increasing and thickness decreasing at midcycle); hence, participants could be stratified as midcycle vs. the early proliferative or luteal phases. We emphasize that this is an illustration of one type amongst many sensitivity analyses that can contribute to identifying, quantifying and accounting for the sources of variability in vaginal microbicide pharmacokinetics.

4. Translating PK to PD

In the microbicides field, pharmacodynamic activity is usually measured by challenging in vitro a specimen of tissue, fluid (e.g. as collected from the vagina) or HIV-infectible cells per se with a suspension of infectious HIV (reviewed in paper by Fernandez-Romero et al. in this issue and references therein). The tissue/fluid/cells may be preloaded with an anti-HIV drug via incubation in vitro. Alternatively, an animal may be dosed with an anti-HIV drug delivery product followed by harvesting of vaginal mucosal tissue, fluid, and/or infectible cells therein; the tissue/fluid/cells are then exposed to a suspension of infectious HIV in vitro. In both cases, the conditions of HIV inoculation (suspension concentration, incubation time) are standardized. Drug concentration in the target matrix (assumed uniform because of the relatively long exposure to drug) is measured. If cells are the target matrix, their concentration is measured, and concentration of drug therein. Measures of the reduction in infectious HIV and/or infection in the tissue/fluid/cells can then be related to drug concentrations in those matrices to establish a dose response curve; summary measures such as EC50 and EC90 values are then computed. Inferences about PD can also be drawn from studies in which a HIV-infectible animal (primarily primates exposed to SHIV) is treated with a vaginal microbicide product followed by inoculation with a suspension of infectious virions. Different animal dosing protocols can be followed leading to inferences about the dose response, albeit not formally computing it per se [47, 48].

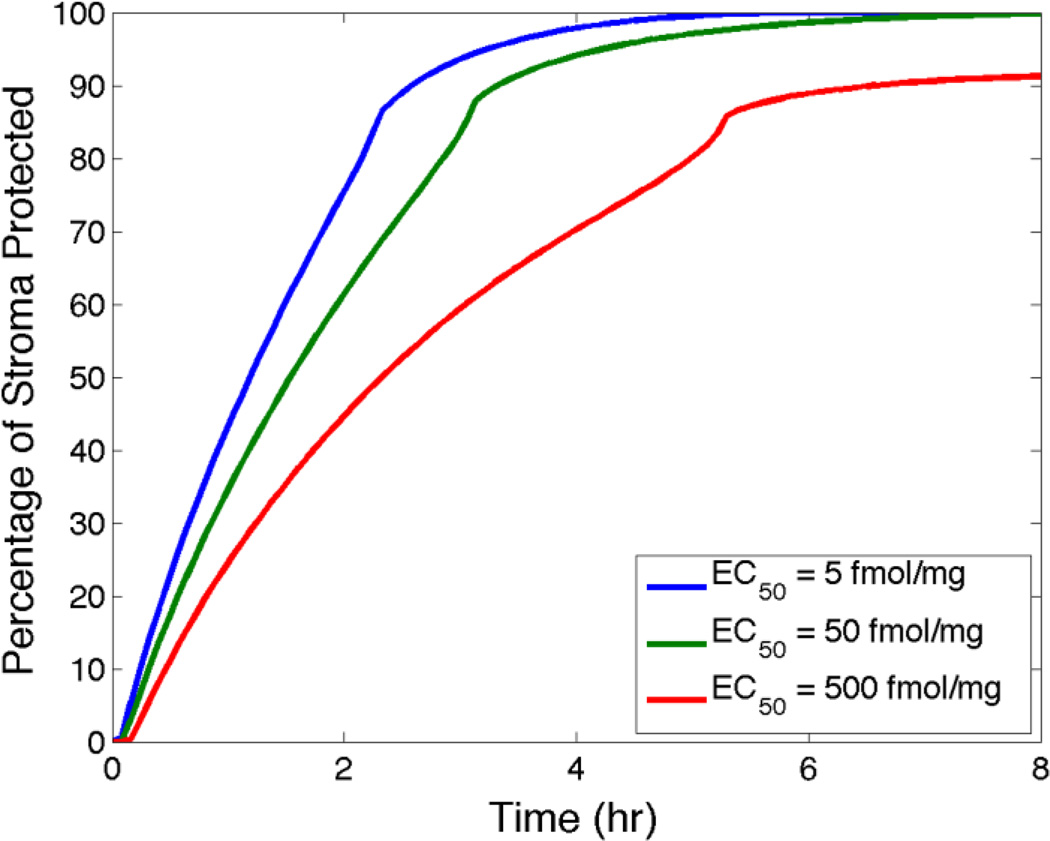

We can use the measured EC50 value for a drug, e.g. TFV-DP, as a reference for predictions by models of concentrations of it in target tissues and/or cells [39, 40, 49]. The following computations illustrate this for the clinical 1% TFV gel, focusing upon TFV-DP concentrations in stromal HIV-infectible host cells. Notably, knowing cell density in the stroma (assumed uniform) enables application for a human vagina with average morphometric dimensions and 4 mL of the TFV gel inserted to the fornix. The model computes the instantaneous fraction of overall stromal volume in which local TFV-DP concentration equals/exceeds the reference EC50 value. This is a measure of predicted PD, which we term “percent protected”, PP. It can be plotted vs. time for specified values of the EC50, and other parameters of the problem (e.g. gel volume and loaded TFV concentration). At present, there are no definitive values of the EC50 for TFV-DP in the vaginal environment. It has been found that different HIV-infectible cell types achieve different concentrations of TFV-DP and appear to have different TFV-DP dose response behavior which, in turn, may be modulated by the menstrual cycle, see [50, 51] and references therein. Therefore, at this stage of model development and application, we conservatively consider a 2 log range in the EC50 value based upon the range of studies of the HIV prevention abilities of TFV-DP and TFV in different cell types and tissues (see article by Fernandez-Romero in this issue, and references therein). Figure 5 plots percent protected vs. time for three values of the EC50 spaced a log apart.

Figure 5.

Values of percent protected in stroma vs. time for three log-spaced values of the target EC50 value.

From Figure 5 we see that increasing the EC50 slows the initial, relatively rapid rise of percent protected by several hours. The kinks in the curves reflect a rebound effect of TFV-DP when its diffusion front reaches the lower stromal boundary. However, there is a relatively small reduction in the peak values of percent protected (about 10%) with the 2-log increase in EC50. This may be more sensitive to other factors, e.g. gel volume and viscosity. Overall, the plots in Figure 5 illustrate how the time-dependent behavior of the percent protected measure can provide insights about: (1) the time interval to protection after gel insertion; (2) the magnitude of that protection; and (3) the duration of that protection.

5. Effects of different gel dosage regimens

The requisite timing of vaginal product dosing depends upon the kinetics of drug delivery by the product and the conditions under which its therapeutic or prophylactic actions must occur. The latter involve behavioral as well as pharmacological factors. For example, the timing of a microbicide product insertion in relation to the subsequent onset of sexual activity would be critical to the prophylactic effect against HIV infection. The product must establish threshold concentrations of drug at target sites prior to the potential arrival of infectious HIV virions. However, there are human factors that limit the specification of such timing, for single or multiple product doses. Behavioral studies have shown, for example, that users are motivated by a great many factors in willingness to insert a microbicide gel as instructed, including the sensory perceptions and preferences by both partners of the gel and their notions of the prophylactic potential of the gel and the risk of infection [52, 53]. The former have been found to relate, in part, to the rheological properties of gels and thus do link to drug delivery [52]. In contrast, use of a gel to deliver systemically acting hormones or topical antifungal agents, for example, may be more tolerant of variations in the timing of insertion: because minimizing the interval to gel pharmacological activity may be less urgent to the user. Here, we will use our deterministic model to consider different dosing intervals for the 1% Tenofovir vaginal microbicide gel.

In Phase 3 clinical trials of a 1% Tenofovir gel, inserted in a 4 mL volume, two dosing regimens have been specified. In the first (CAPRISA 004) and third (FACTS 001) trials, there was a before-and-after sex gel application regimen (termed BAT24). The pre- and post-sex intervals were specified as ≤ 12 hours. In the second trial (VOICE) participants were instructed to insert gel daily (at the same time) regardless of sexual activity. The CAPRISA 004 trial had a positive result overall in demonstrating efficacy against HIV transmission[54]. However, the VOICE and FACTS 001 trials had negative overall results[55, 56]. In both trials there was very low user adherence to specified gel dosing, and the negative overall trial results have been attributed significantly to such poor adherence. In the CAPRISA 004 trial, there were data indicating that increased adherence to specified gel dosing resulted in greater anti-HIV efficacy. In both the VOICE and FACTS 001 trials there was some evidence of efficacy in the subsets of participants who did consistently apply gel. Thus, there is pharmacological evidence that application of 4 mL of the 1% Tenofovir gel can distribute drug adequately to reduce HIV transmission. However, these trials give behavioral evidence that this combination of gel and applied volume is not acceptable epidemiologically in the target populations in the developing world.

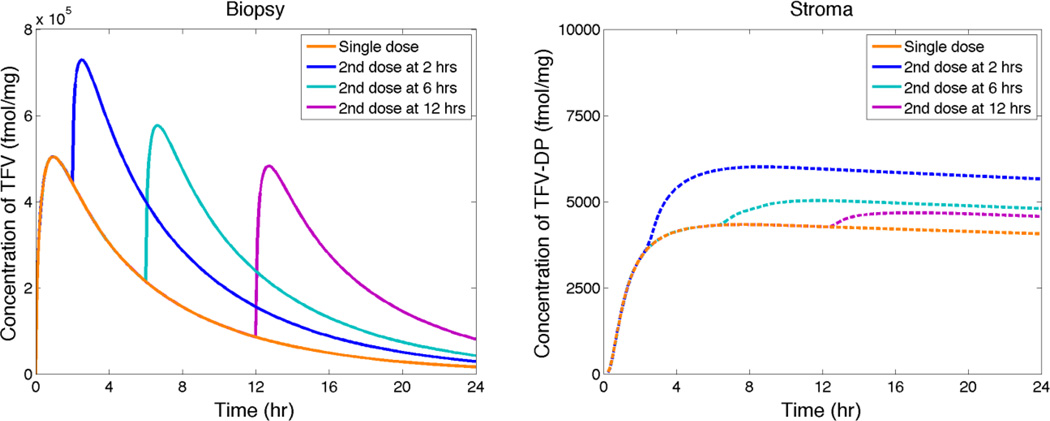

Modeling can contribute to our understanding (and optimization) of pharmacological effects of the frequency of gel (and any delivery system) dosing. It can also help understand the determinants of user sensory perceptions and preferences of microbicide gels and other products, as noted above[52, 53]. The dosage regimens in the Tenofovir gel trials both involved a second insertion of gel at a varying interval after the first insertion. This can be simulated using our modeling approach, allowing for residual gel that has not leaked from the vagina and, when there is sexual activity, the presence of semen as an additional local fluid that mixes with gel. Here, we restrict analysis to the first scenario of repeated gel application at varying intervals without coitus. As PK measures of relevance, we again consider model simulation of Tenofovir concentration measured in a homogenized biopsy and of volume averaged Tenofovir Diphosphate concentration in the stromal compartment. Results are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Model simulations of concentrations of TFV measured in biopsies and of TFV-DP in stroma vs. time after initial gel insertion. A second gel insertion is performed at times given in the figure.

In Figure 6 we see that a relatively rapid second dosing with gel (at 2 hrs) increases Cmax for TFV in a biopsy by about 50%, as tmax increases to about 4 hrs. Second doses at 6 or 12 hs have lesser effects, because of the greater decreases in concentration of TFV before the second dose. The stromal average concentration of TFV-DP increases by about 60`% after the early second dose, and by <20% after the two later dose conditions. The plots in Figure 6 (linear scale; for a single dose) and the corresponding plot line in the Figure 4 (log scale) show that maximum volume average TFV-DP levels in the stroma occur about 4 hours after insertion of 4 mL of the TFV gel. Of course, these computations have omitted coitus and semen deposition. They are intended to illustrate the use of deterministic modeling to evaluate the gel dosing sensitivity of vaginal microbicide PK.

6. Interpreting consequences of gel aging during storage

Gel products are given a shelf life that derives from testing changes in their properties and drug payload over time. These include measures of toxicity and stability of their drug(s), and also viscosity. During gel development such longevity analysis is undertaken via accelerated aging experiments, in which gel is placed in an oven maintained at elevated temperatures, e.g. 40°C, and sampled monthly. Typically, the measurements of viscosity are at a single shear strain rate (e.g. 1 sec−1) and these show a graduate decline in its value. The decline reflects changes in the polymer microstructure of the gel such as lowered interconnectivity and shortened chain length. Details of the molecular mechanisms of gel aging notwithstanding, it is of interest to understand how much the reduction in gel viscosity over time may contribute to altered vaginal deployment and vaginal drug distribution. We can use our gel model system to study this problem, applying it to accelerated aging data from a prototype microbicide gel (labeled 3002) designed to deliver the drug IQP-0528 (gel kindly provided by ImQuest Biosciences, Frederick, MD). We received raw data on viscosity vs. shear strain rate in rheometric experiments conducted at 37°C. Conditions of measurement were similar to those used in prior studies by our group [30, 31]. We processed these data as obtained for fresh gel and for gel that had been subjected to one year of aging at 40°C. Rheological parameters for the Carreau like constitutive model were computed [30–32], and input to our model. Results are presented in Figures 7 – 9.

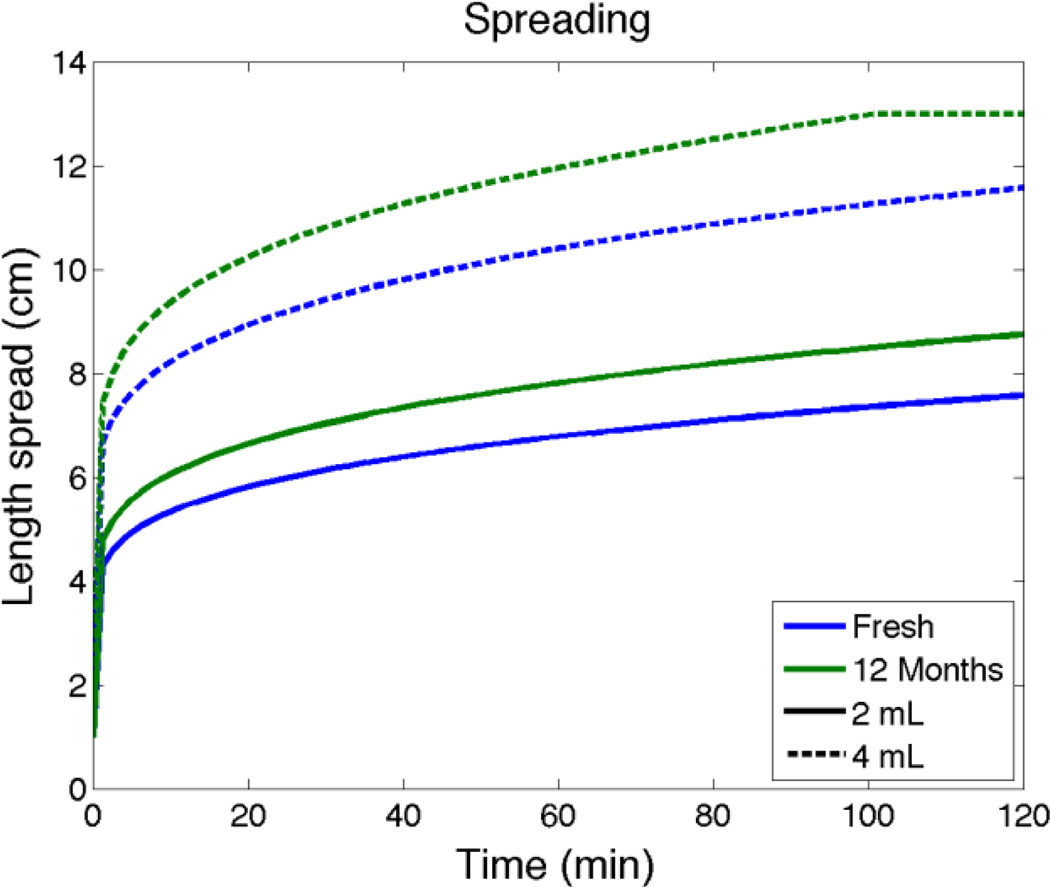

Figure 7.

Model predictions of distances that gel has spread along the vaginal canal for fresh gel vs. 12 months of accelerated aging. Data for the prototype microbicide gel inserted to the fornix is a vaginal canal of average dimensions (see above; the length of the canal is 13 cm). The line for 4 mL of aged gel becomes horizontal at the moment the gel has completed coating the entire length of the canal (subsequent to which it begins to leak).

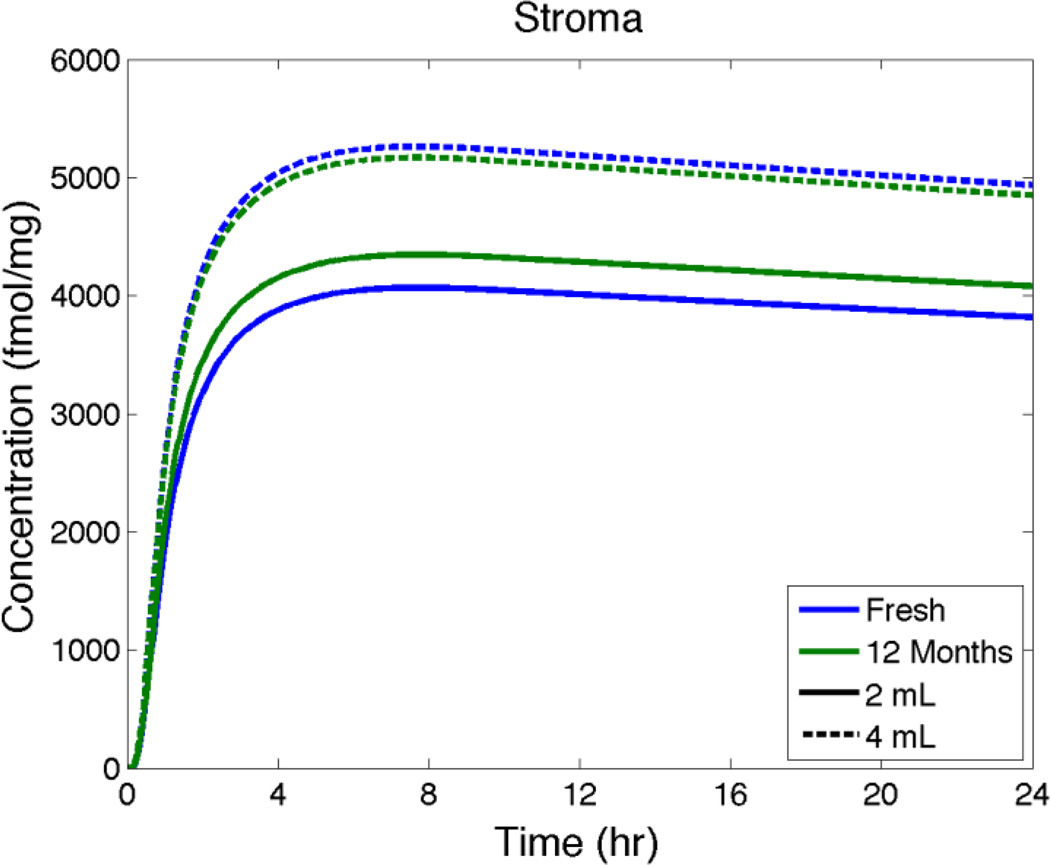

Figure 9.

Model predictions of average TFV-DP concentration in the stroma vs. time after insertion for fresh vs. aged gel (as in Figure 7).

Spreading predictions in Figure 7 show that 2 mL and 4 mL of aged gel spread about 14% further than fresh gel in 2 hours after gel insertion. Figure 8 predicts that there are relatively small increases in Cmax (< 10%) and essentially no changes in tmax for TFV in a biopsy for fresh vs. aged gel. Figure 9 also indicates that there are very small differences in TFV-DP concentrations in the stroma for fresh vs. aged gel. Overall, then, these computations suggest that the reduction in viscosity over a year of accelerated aging of this gel has a quantitatively small and likely pharmacologically insignificant effect on gel deployment and drug delivery.

Figure 8.

Model predictions of average TFV concentration in a biopsy vs. time after insertion for fresh vs. aged gel (as in Figure 7).

7. Comparing vaginal distributions of drugs delivered from gels vs. rings

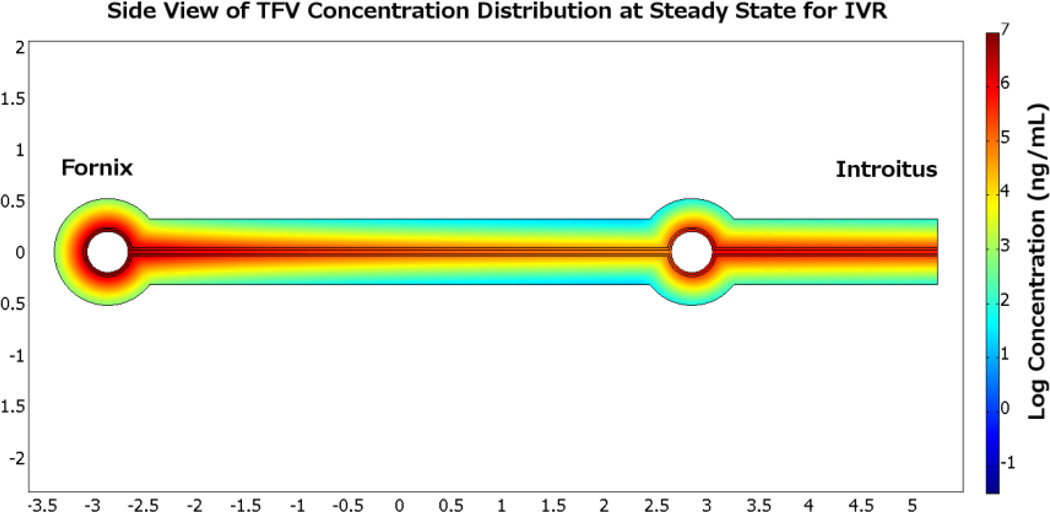

Drug release, transport and vaginal distribution are different for a deformable gel than a solid intravaginal ring (IVR). A pharmacologically relevant comparison is for delivery of microbicides. The gel is intended to deliver drug over a relatively short time scale (≤ one day) while the ring is intended to delivery drug over an interval of one to several months. Analyzing and comparing the kinetics of drug concentrations in target vaginal mucosa as delivered by these dosage forms is informative with respect to several key considerations, including: (1) time to protection; and (2) duration of that protection. We extended our original model of drug release to vaginal epithelium by an IVR [36] to include diffusive drug transport into and through vaginal epithelium and stroma [57]. We illustrate the comparison of the kinetics of drug delivery by an IVR vs. a gel by applying that model to delivery of Tenofovir and comparing it to TFV delivery by the 1% clinical gel.

The ring used here is 5.7 cm by 5.0 cm with a diameter of 0.4 cm. Drug release rate is 10 mg/day. Drug transport from a ring to tissue is fundamentally a three dimensional problem; however such a problem can be reduced by dimensional analysis. The two important dimensions are the direction of vaginal flow, where drug is being transported, and the orientation of tissue through which drug diffuses. Transport in the lateral third dimension is quasi steady, and is neither fast enough to significantly alter drug distribution in vaginal fluid nor slow enough to be the rate limiting step of transport into the tissue. Figure 10 illustrates results in steady state for Tenofovir concentration distribution in the plane cut through the middle of the ring; the left empty circle is the cross section of the ring near the fornix and the right circle is the cross section near the introitus. The units of concentration are log (base 10) ng/mL, with a high of 107 ng/mL and a low of 102 ng/mL. Highest concentrations of drug are found around the two sections of the ring and in the vaginal fluid. Lowest concentrations are deep in the tissue furthest downstream from the ring. Vaginal fluid production rate (here taken as 6 mL/day) determines the magnitude of convection and is the driving force in drug transport along the canal.

Figure 10.

Heat map plot of Tenofovir concentration distribution at steady state for an intravaginal ring. Comparison of TFV concentration distributions achieved by the gel and IVR can be made by plotting the average concentration in each compartment as a function of time, cf. Figure 11.

During the course of the first day, the gel achieves much higher concentration initially compared with the ring. This result is not surprising considering a 4mL 1% gel contains 40 mg of drug, but the ring can only release 10 mg in a day. The maximum concentration for a gel is achieved within the first few hours and drops gradually, while the concentration for the ring rises gradually and continues to do so after the first day. This illustrate that a gel can be effective within a few hours after insertion, but ring insertion requires a longer interval, of the order of a day.

8. Planning and interpreting studies across species: size matters

In the interpretation of models in transport theory, the concept of ‘scale’ is central: (1) time scales over which processes manifest and concentrations change; and (2) spatial scales, e.g. in the sizes of individual domains (compartments) within which drugs move, and in the magnitudes of concentration gradients within those domains. Formal mathematical transport theory exploits the magnitudes of scales of time and space in making comparisons of magnitudes of measures of transport (e.g. mass delivered), including manipulating the governing equations in order to simplify as well as interpret them [45]. More generally, the importance of scale, viz. body size, is central to the use of allometric scaling in biology. However, caveats have been expressed regarding application of the traditional allometric scaling approaches to drug delivery [58–60].

As we design and conduct studies of vaginal drug distribution in animal models, issues of scale are central, e.g. differences in dimensions of drug compartments, as well as familiar pharmacological and biological distinctions such as in tissue structure, cell and molecular specificities, endocrine factors, immunological responses, etc. We can use modeling to provide guidance in comparing results across species. An informative example is selecting the size of the dosage vehicle, e.g. gel volume or vaginal ring diameter. We assume that the goal of the modeling is to predict and help interpret target concentrations of drug in a target mucosal compartment (as in computation of the percent protected for Tenofovir Diphosphate concentration in stroma, given above) and that these concentrations are the same in the human and an animal model. We fix gel volume in the human and want to deduce the volume for the animal that will deliver drug to the target compartment with the same concentration kinetics as in the human. We illustrate this exercise first with a simple algebraic approximation, typical of scaling arguments in transport theory, and then with a more complete numerical solution of the transport equations across species. For the sake of this exercise, we assume that the thicknesses of the epithelial and stromal layers are similar between the two species. This assumption can be relaxed, but it simplifies the analyses and interpretations here, which are intended to illustrate the use of modeling. First we focus on a best case scenario in which the gel with a uniform thickness h coats the entire mucosal surface. Drug transport down into the mucosal tissue depends upon h and because we wish to equate mucosal concentrations (rather than total masses of drug) across species, the value of h is conserved in this exercise (so that concentration gradients in gel are the same across species). Suppose that the surface area of the mucosa (assumed flat) is A and gel volume is V. Then V = Ah, so that h = V/A. Thus V/A must be conserved across species. That is, the ratio of gel volume to mucosal surface area must be the same in the animal model as in the human. Note that this rule pertains to achieving comparable drug concentrations in a completely coated mucosa, not equating masses of drug delivered. For that latter case, similar analysis indicates that the ratio of gel volume to the square of mucosal surface area, V/A2, must be conserved.

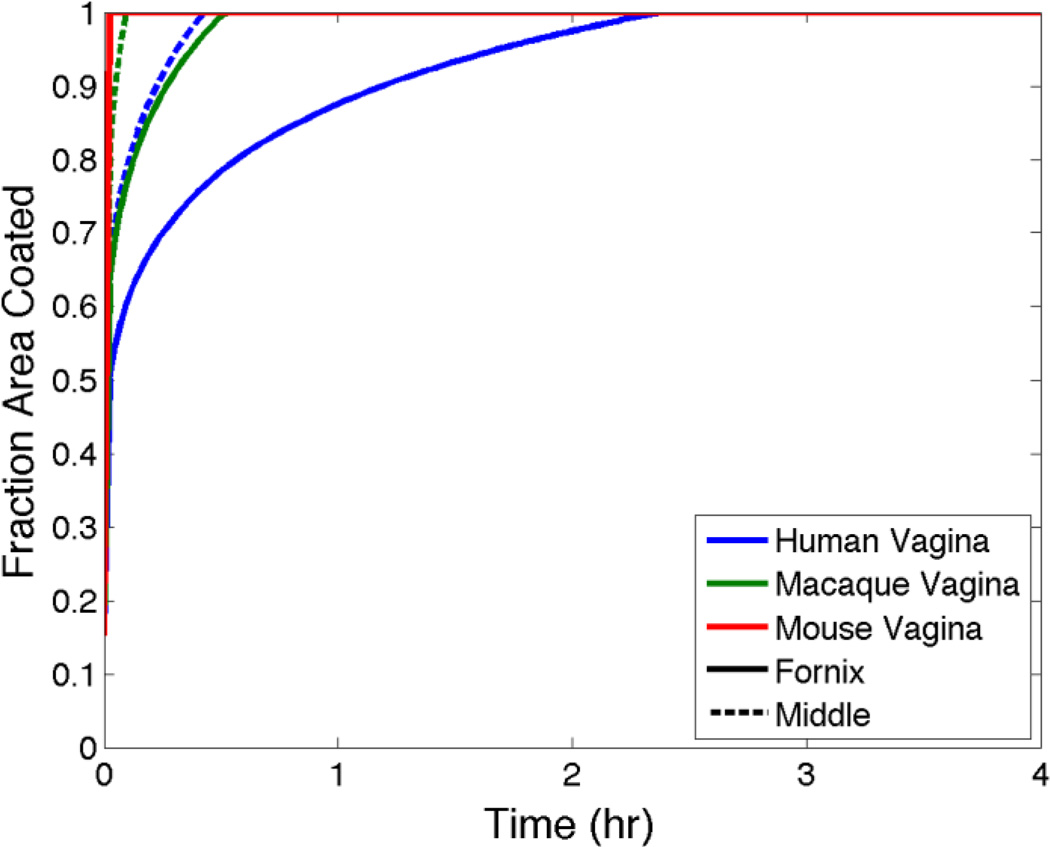

The preceding simple analysis is for essentially a quasi-steady state gel coating scenario. As the computations above illustrate, the kinetics of gel spreading play a critical role in the time to such quasi-steady state, or to the time to maximum gel coverage and instantaneous drug release to mucosal surfaces. Here, such simple scaling rules do not exist. However, we can use modeling to gain insights into how gel volume affects gel spreading rate across species. Figure 12 shows model predictions of area coated (normalized by total mucosal surface area) vs. time for the 1% Tenofovir gel as applied to a human vs. a rhesus macaque and a mouse. These are representative computations that compare the consequences of differences in vaginal size. Gel volume is scaled by vaginal surface area, as for the steady state example above, and is 4 mL for the human. Representative vaginal dimensions are: (1) human, length = 13.35 cm, width = 3 cm; (2) macaque (measured in excised vaginal specimens) length = 7 cm, width = 3 cm, gel volume = 1.93 mL; and (3) mouse[61] length = 1 cm, width = 0.5 cm, gel volume = 0.45 mL.

Figure 12.

Fractional vaginal surface area coated vs. time, predicted by the model for the 1% Tenofovir gel for human, macaque and murine sized vaginal canals. Gels are inserted to either the fornix or mid canal. Further details are given in text.

Figure 12 gives the striking result that there are substantial differences in the rates of vaginal coating across the three species. Results for the human predict about 2 hours for complete coating. For the macaque, this interval is about 30 minutes, and for the mouse < 10 min are required for complete vaginal coating. This preliminary analysis of the trans-species problem gives a caveat regarding comparisons of gel distribution (and, by implication, consequent drug delivery and PK) in humans vs. animals with smaller vaginas. While dose volumes in the animals must obviously be smaller, the choice of those volumes is not simple – if details of PK are expected to be similar across the species.

9. How Accurate is the Modeling?

Convincing demonstration of the accuracy of vaginal drug distribution modeling is direct comparison of its predictions to corresponding measurements of drug concentrations in living in vivo systems. The latter are obtained in PK studies, and in principle models can be applied to specific dosing and other conditions of such counterpart experiments. Such comparisons are, however, constrained by experimental factors – biological, behavioral and technological – including: (1) uncontrolled variability in human/animal physiology and anatomy (e.g. variations in vaginal size, fluid content and epithelial thickness due to varying cycle phase and body size); (2) uncontrolled variability in conditions of dose application (e.g. timing and, for a gel, true volume and site of insertion into the canal); and (3) limitations in sampling material (tissue, fluids) from different vaginal compartments, and in accurate measurement of drug concentrations therein. In section 3 of this article, we analyzed consequences of variations in parameters characterizing factors (1) and (2) on model predictions. We have compared predictions of the gel model vs. experimental data for a single insertion of 4 mL of the 1% Tenofovir gel in a human PK study[38]. Those data provide volume-averaged concentrations of TFV in aspirated vaginal fluid, a vaginal biopsy and blood. We used the model to compute volume-averaged concentrations in its compartments, simulating the biopsy as the combined epithelial and stromal compartments [41]. Cmax and C24 values of model vs. data were compared for biopsies and blood, with the following results.

The magnitudes of these differences are small compared to the variability in the human PK results, and are an encouraging initial comparison of predictions of this model with in vivo data.

Predictions of models can also be applied to in vitro experiments of drug transport into and through tissue specimens. Recently, drug concentrations vs. depth and time in specimens of excised tissue have been measured using confocal Raman spectroscopy applied in a Transwell configuration[62, 63]. Those data can be processed to deduce both diffusion coefficients in the epithelial and stromal layers and partition coefficients at interfaces of vehicle-epithelium and epithelium-stroma (the basement membrane). Results to date with this technique as applied to specimens of fresh excised porcine vaginal tissue show that Tenofovir transport from both its clinical gel and a fluid medium into the tissue specimens exhibits concentration distributions expected from diffusion theory, and a multicompartment unsteady diffusion model has been used to deduce the diffusion and partition coefficients. In principle, this approach can be extended to test model accuracy by inputting parameters obtained in a test set of experiments to model predictions that are compared with additional trial experiments.

10. Discussion

In this article we have reviewed foundations of deterministic modeling of vaginal drug distribution, as applied specifically to locally acting drugs such as microbicides. Quantitative results were obtained for the microbicide drug Tenofovir, and its anti-HIV phosphorylate Tenofovir Diphosphate. However, the methodological framework here can be applied across multiple drug types. We presented an application of modeling to assist in understanding the sources of variability in vaginal drug distribution measurements, and their sensitivities to gel use characteristics. This showed, for example, how natural biological variability in vaginal size and epithelial thickness in gel users influences vaginal drug distribution. We illustrated use of the modeling to help improve fundamental understanding of phenomena such as the translation of pharmacokinetic information to insights about pharmacodynamic activity (exemplified in computation of the percent protected measure for vaginal stromal tissue by Tenofovir Diphosphate). In this process, the modeling helps us address three key features of microbicide functionality: (1) time to onset of prophylactic activity; (2) the level of that activity; and (3) the duration of that activity. We compared vaginal distributions of Tenofovir achieved by two primary vaginal microbicide dosage forms (gels and intravaginal rings), showing how the intervals between product insertion and maximum mucosal drug levels differ between them. We considered effects of multiple gel doses of Tenofovir. Rings create reservoirs of TFV-DP in stroma that are maintained for weeks and even months. In contrast, gels require repeated application to sustain such TFV-DP levels. However, gels achieve these levels much more quickly than do rings. Modeling can help provide guidelines for designing dosage regimens that achieve requisite vaginal concentration distributions for specified intervals for drugs such as microbicides. We also applied the modeling to address practical pharmaceutical questions in microbicide product development, i.e. effects of changes in gel viscosity due to aging. Finally, we addressed the need to conduct microbicide vaginal drug distribution studies in multiple species with differing vaginal sizes as well as other characteristics. Here we showed that gel spreading and vaginal drug distribution occur more rapidly as the anatomical size of the vagina diminishes. This distinction should be taken into account in design of animal studies to maximize their relevance to human PK and PD.

We emphasize that the computations presented here are intended to illustrate the uses of modeling of vaginal drug distributions, and are not the last word on quantitative details of the phenomena addressed. We have emphasized modeling of gel delivery systems, because there are considerably more experience and data about them than intravaginal rings (the next most studied microbicide dosage form) and films, foaming tablets, fiber meshes, suppositories, etc. However, the modeling approach can and should be applied to these alternative vehicles[64]. In principle, deterministic modeling can be complementary to empirical PK modeling methodology. A worthwhile goal is to merge the best of these two modeling perspectives. Use of modeling to improve our understanding of the determinants of vaginal drug distribution can be translated into improved methodology for product performance evaluation and design. Computations are relatively quick compared to experiments about drug distribution, and can be used to simulate large numbers of such experiments, both in vitro and in vivo. This can guide prospective experimental design, not just retrospective interpretation. In so doing, important questions can be rationally addressed, relating, for example, to the compositions and sizes of vaginal drug delivery vehicles, the loaded drug concentrations, the frequencies at which the products should be applied to achieve and sustain target drug levels, and best times after product insertion at which experimental sampling of vaginal fluids and tissue should be performed to maximize interpretation of concentrations measured therein.

Figure 1.

Drawing of human vaginal canal and mucosal tissue (not to scale). The canal contains gel that partially coats the mucosal surface (anti-pathogenic microbicide molecules are depicted as red dots), and there is semen in the lumenal space not occupied by gel. On the left is a column that represents the tissue collected by a punch biopsy, typically used to collect tissue for measuring drug concentration in pharmacokinetic studies.

Figure 3.

Concentration distributions at 1, 4, 12 and 24 hours after insertion of 4 mL of 1% TFV gel to the vaginal fornix. Gel spreads from right-to-left. This view shows the upper half plane of the domain of the problem (cf. Fig 2).

Figure 11.

Comparison of volume averaged TFV concentrations vs. time for the 1% TFV gel vs. an intravaginal TFV releasing ring. For details see text.

Table 2.

Differences of model predictions vs. human PK data for the 1% Tenofovir gel applied at volume 4 mL.

| Biopsy | Blood | |

|---|---|---|

| Cmax(ng/mL) | −5.5% | 19.4% |

| C24 (ng/mL) | 12.2% | −2.4% |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH HD 072702 and AI 077289. We thank Dr. Anthony Ham of Imquest Biosciences for providing the data on gel aging, and Dr. James Smith of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing data on the dimensions of the rhesus macaque vagina.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barnhart KT, Izquierdo A, Pretorius ES, Shera DM, Shabbout M, Shaunik A. Baseline dimensions of the human vagina. Human Reproduction. 2006;21:1618–1622. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little, Brown; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owen DH, Katz DF. A vaginal fluid simulant. Contraception. 1999;59:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(99)00010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison PF, Rosenberg Z, Bowcut J. Topical microbicides for disease prevention: status and challenges. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1290–1294. doi: 10.1086/374834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faundes A, Brache V, Alvarez F. Pros and cons of vaginal rings for contraceptive hormone delivery. Am J Drug Deliv. 2004;2:241–250. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander NJ, Baker E, Kaptein M, Karck U, Miller L, Zampaglione E. Why consider vaginal drug administration? Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brannon-Peppas L. Novel vaginal drug release applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1993;11:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 8.das Neves JJ, Bahia MMF. Gels as vaginal drug delivery systems. 2006;318:14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobaria N, Mashru R, Vadia NH. Vaginal drug delivery systems: a review of current status. East and Central African Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2007;10:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussain A, Ahsan F. The vagina as a route for systemic drug delivery. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2005;103:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balzarini J, Van Damme L. Microbicide drug candidates to prevent HIV infection. Lancet. 2007;369:787–797. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hladik F, Hope TJ. HIV infection of the genital mucosa in women. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2009;6:20–28. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone A. Microbicides: A new approach to preventing HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:977–985. doi: 10.1038/nrd959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuo PY, Sherwood JK, Saltzman WM. Topical antibody delivery systems produce sustained levels in mucosal tissue and blood. Nature biotechnology. 1998;16:163–167. doi: 10.1038/nbt0298-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saltzman WM, Sherwood JK, Adams DR, Haller P. Long-term vaginal antibody delivery: delivery systems and biodistribution. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2000;67:253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dosage Forms and Delivery Systems for Vaginal Therapy (Special Issue) Pharmaceutics. 2014;6 [Google Scholar]

- 17.das Neves J, Sarmento B. Drug Delivery and Development of Anti-HIV Microbicides. Singapore: Pan Stanford; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz DF. Biophysics, Drug Transport Modeling and Microbicides. In: das Neves J, Sarmento B, editors. Drug Delivery and Development of Anit-HIV Microbicides. Singapore: Pan Stanford Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saltzman WM. Drug delivery: engineering principles for drug therapy. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truskey GA, Yuan F, Katz DF. Transport phenomena in biological systems. Upper Saddle River NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrix CW, Cao YJ, Fuchs EJ. Topical Microbicides to Prevent HIV: Clinical Drug Development Challenges. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2009;49:349–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Niekerk N, Nuttall J, Zeiser S, Nel A. Population pharmacokinetic modelling of dapivirine. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30:A38–A39. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang K-H, Schwartz JL, Sykes C, Doncel GF, Kashuba ADM. Population pharmacokinetic model of vaginal tenofovir 1% gel in the cervicovaginal fluid. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30:A38–A38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendrix CW, Chen BA, Guddera V, Hoesley C, Justman J, Nakabiito C, Salata R, Soto-Torres L, Patterson K, Minnis AM, Gandham S, Gomez K, Richardson BA, Bumpus NN. MTN-001: randomized pharmacokinetic cross-over study comparing tenofovir vaginal gel and oral tablets in vaginal tissue and other compartments. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saltzman W. Drug delivery: Engineering principles for drug therapy. 1 ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz DF, Gao Y, Kang M. Using modeling to help understand vaginal microbicide functionality and create better products. Drug Delivery and Translational Research. 2011;1:256–276. doi: 10.1007/s13346-011-0029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kieweg SL, Katz DF. Squeezing flows of vaginal gel formulations relevant to microbicide drug delivery. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering-Transactions of the Asme. 2006;128:540–553. doi: 10.1115/1.2206198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kieweg SL, Katz DF. Interpreting properties of microbicide drug delivery gels: Analyzing deployment kinetics due to squeezing. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2007;96:835–850. doi: 10.1002/jps.20774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szeri AJ, Park SC, Verguet S, Weiss A, Katz DF. A model of transluminal flow of an anti-HIV microbicide vehicle: Combined elastic squeezing and gravitational sliding. Physics of Fluids. 2008;20 doi: 10.1063/1.2973188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tasoglu S, Katz DF, Szeri AJ. Transient spreading and swelling behavior of a gel deploying an anti-HIV topical microbicide. J Nonnewton Fluid Mech. 2012;187–188:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jnnfm.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tasoglu S, Park SC, Peters JJ, Katz DF, Szeri AJ. The consequences of yield stress on deployment of a non-Newtonian anti-HIV microbicide gel. J Nonnewton Fluid Mech. 2011;166:1116–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.jnnfm.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tasoglu S, Peters JJ, Park SC, Verguet S, Katz DF, Szeri AJ. The effects of inhomogeneous boundary dilution on the coating flow of an anti-HIV microbicide vehicle. Physics of Fluids. 2011;23:93101–931019. doi: 10.1063/1.3633337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ham AS, Ugaonkar SR, Shi L, Buckheit KW, Lakougna H, Nagaraja U, Gwozdz G, Goldman L, Kiser PF, Buckheit RW., Jr Development of a combination microbicide gel formulation containing IQP-0528 and tenofovir for the prevention of HIV infection. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:1423–1435. doi: 10.1002/jps.23026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahalingam A, Smith E, Fabian J, Damian FR, Peters JJ, Clark MR, Friend DR, Katz DF, Kiser PF. Design of a Semisolid Vaginal Microbicide Gel by Relating Composition to Properties and Performance. Pharmaceutical Research. 2010;27:2478–2491. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiser PF, Mahalingam A, Fabian J, Smith E, Damian FR, Peters JJ, Katz DF, Elgendy H, Clark MR, Friend DR. Design of tenofovir-UC781 combination microbicide vaginal gels. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:1852–1864. doi: 10.1002/jps.23089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geonnotti AR, Katz DF. Compartmental Transport Model of Microbicide Delivery by an Intravaginal Ring. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2010;99:3514–3521. doi: 10.1002/jps.22120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao Y, Katz DF. Multicompartmental pharmacokinetic model of tenofovir delivery by a vaginal gel. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz JL, Rountree W, Kashuba ADM, Brache V, Creinin MD, Poindexter A, Kearney BP. A multi-compartment, single and multiple dose pharmacokinetic study of the vaginal candidate microbicide 1% tenofovir gel. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao Y, Yuan A, Katz DF. Mass transport theory improves compartmental PK modeling of microbicides and helps guide product science and development. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30:A147–A147. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao Y, Yuan A, Katz DF. Tenofovir diphosphate concentrations in human vaginal stroma after different dosage regimens with a vaginal gel: a modeling approach. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30:A258–A259. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao Y, Yuan A, Chuchuen O, Ham A, Yang KH, Katz DF. Vaginal deployment and tenofovir delivery by microbicide gels. Drug Delivery and Translational Research. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13346-015-0227-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuchuen O, Henderson MH, Sandros MG, Kashuba ADM, Katz DF. Transport and transport properties of tenofovir from microbicide gels into vaginal tissue: analysis using Raman spectroscopy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30:A59–A60. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pendergrass PB, Belovicz MW, Reeves CA. Surface area of the human vagina as measured from vinyl polysiloxane casts. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation. 2003;55:110–113. doi: 10.1159/000070184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chuchuen O, Henderson MH, Sykes C, Kim MS, Kashuba ADM, Katz DF. Quantitative analysis of microbicide concentrations in fluids, gels, and tissues using confocal Raman spectroscopy. PLoS One. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Truskey G, Yuan F, Katz D. Transport Phenomena in Biological Systems. 2 ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patton DL, Thwin SS, Meier A, Hooton TM, Stapleton AE, Eschenbach DA. Epithelial cell layer thickness and immune cell populations in the normal human vagina at different stages of the menstrual cycle. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;183:967–973. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.108857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dobard C, Sharma S, Martin A, Pau CP, Holder A, Kuklenyik Z, Lipscomb J, Hanson DL, Smith J, Novembre FJ, Garcia-Lerma JG, Heneine W. Durable protection from vaginal simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection in macaques by tenofovir gel and its relationship to drug levels in tissue. Journal of virology. 2012;86:718–725. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05842-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nuttall J, Kashuba A, Wang R, White N, Allen P, Roberts J, Romano J. Pharmacokinetics of tenofovir following intravaginal and intrarectal administration of tenofovir gel to rhesus macaques. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:103–109. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00597-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao Y, Yuan A, Katz DF. Modeling of gel flow and drug transport in the vaginal mucosa for better microbicide gel design. Annual meeting of Biomedical Engineering Society; San Antonio, TX. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Louissaint NA, Cao YJ, Skipper PL, Liberman RG, Tannenbaum SR, Nimmagadda S, Anderson JR, Everts S, Bakshi R, Fuchs EJ, Hendrix CW. Single dose pharmacokinetics of oral tenofovir in plasma, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, colonic tissue, and vaginal tissue. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29:1443–1450. doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen Z, Fahey JV, Bodwell JE, Rodriguez-Garcia M, Kashuba AD, Wira CR. Sex hormones regulate tenofovir-diphosphate in female reproductive tract cells in culture. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morrow KM, Fava JL, Rosen RK, Vargas S, Shaw JG, Kojic EM, Kiser PF, Friend DR, Katz DF P.L.S. Team. Designing Preclinical Perceptibility Measures to Evaluate Topical Vaginal Gel Formulations: Relating User Sensory Perceptions and Experiences to Formulation Properties. Aids Research and Human Retroviruses. 2014;30:78–91. doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van den Berg JJ, Rosen RK, Bregman DE, Thompson LA, Jensen KM, Kiser PF, Katz DF, Buckheit K, Buckheit RW, Morrow KM. "Set it and Forget it": Women's Perceptions and Opinions of Long-Acting Topical Vaginal Gels. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:862–870. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0652-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karim QA, Karim SSA, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, Kharsany ABM, Sibeko S, Mlisana KP, Omar Z, Gengiah TN, Maarschalk S, Arulappan N, Mlotshwa M, Morris L, Taylor D, Grp CT. Effectiveness and Safety of Tenofovir Gel, an Antiretroviral Microbicide, for the Prevention of HIV Infection in Women. Science. 2010;329:1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rees H, Delany-Moretlwe S, Baron D, Lombard C, Gray G, Myer L, Panchia R, Schwartz J, Doncel G. FACTS 001 Phase III Trial of Pericoital Tenofovir 1% Gel for HIV Prevention in Women. Washington: CROI, Seattle; 2015. p. 26LB. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeanne Marrazzo GR, Nair G, Palanee T, Mkhize B, Nakabiito C, Taljaard M, Piper J, Gomez Feliciano K, Chirenje M and VOICE Study Team. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV in Women: Daily Oral Tenofovir, Oral Tenofovir/Emtricitabine, or Vaginal Tenofovir Gel in the VOICE Study (MTN 003). Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Atlanta, Georgia. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katz DF, Gao Y, Chang S. Multi-Compartmental Transport of Anti-HIV Molecules into and through Mucosa. Biophysical Journal. 2012;102:594a. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dedrick RL. Interspecies scaling of regional drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. 1986;75:1047–1052. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600751106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hunter RP. Interspecies allometric scaling. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2010:139–157. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10324-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.West GB, Brown JH. The origin of allometric scaling laws in biology from genomes to ecosystems: towards a quantitative unifying theory of biological structure and organization. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1575–1592. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leckie PA, Watson JG, Chaykin S. An improved method for the artificial insemination of the mouse (Mus musculus) Biol Reprod. 1973;9:420–425. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/9.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chuchuen O, Henderson MH, Sykes C, Kim MS, Kashuba AD, Katz DF. Quantitative analysis of microbicide concentrations in fluids, gels and tissues using confocal Raman spectroscopy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e85124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chuchuen O, Henderson MH, Sandros MG, Kashuba ADM, Katz DF. Transport and Transport Properties of Tenofovir from Microbicide Gels into Vaginal Tissue: Analysis Using Raman Spectroscopy. Aids Research and Human Retroviruses. 2014;30:A59–A60. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tasoglu S, Rohan LC, Katz DF, Szeri AJ. Transient swelling, spreading, and drug delivery by a dissolved anti-HIV microbicide-bearing film. Phys Fluids (1994) 2013;25:31901. doi: 10.1063/1.4793598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]