Abstract

Objectives

To test and develop, using structural equation modelling, a robust model of the mediational pathways through which health warning labels exert their influence on smokers’ subsequent quitting behaviour.

Methods

Data come from the International Tobacco Control Four-Country Survey, a longitudinal cohort study conducted in Australia, Canada, the UK, and the US. Waves 5–6 data (n=4988) were used to calibrate the hypothesized model of warning label impact on subsequent quit attempts via a set of policy-specific and general psychosocial mediators. The finalised model was validated using Waves 6–7 data (n=5065).

Results

As hypothesized, warning label salience was positively associated with thoughts about risks of smoking stimulated by the warnings (β=.58, p<.001), which in turn were positively related to increased worry about negative outcomes of smoking (β=.52, p<.001); increased worry in turn predicted stronger intention to quit (β=.39, p<.001) which was a strong predictor of subsequent quit attempts (β=.39, p<.001). This calibrated model was successfully replicated using Waves 6–7 data.

Conclusions

Health warning labels seem to influence future quitting attempts primarily through their ability to stimulate thoughts about the risks of smoking, which in turn help to raise smoking-related health concerns, which lead to stronger intentions to quit, a known key predictor of future quit attempts for smokers. By making warning labels more salient and engaging, they should have a greater chance to change behaviour.

Keywords: health warnings, quit attempts, mediational pathways, structural equation modelling

INTRODUCTION

This paper uses structural equation modelling (SEM) to test and develop a mediational model of how health warning labels affect quitting; in particular, to contrast a positive influence model, with a reactance model whereby the impacts are counter-productive. SEM provides several advantages over past studies of the impact of health warnings which tended to employ regression-based models for such purpose. The first advantage of SEM is that it allows for the complex relationships between several independent and dependent variables depicting the mediational pathways through which warning labels have their influence on subsequent behaviour to be examined in a single analysis, something that could not be done simultaneously using a regression-based approach. The latter has led to past studies focusing on examining the relationship with quitting activity directly, without reference to general mediators (e.g., (Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009; Hammond, Fong, McDonald, Cameron, & Brown, 2003). Second, SEM typically models key constructs using latent variables where measurement errors of key variables can be accounted for, thus providing for a more rigorous analysis compared to regression analysis which can only accommodate observed variables. Third, SEM is largely a confirmatory technique and thus as an explanatory tool, it is more efficient and better suited for understanding the complex processes involved in how and why warning labels work in changing behaviour than regression-based models which focus more on prediction. To date, the use of mainly regression-based models in warning label impact research has limited our understanding of how and why warning labels work.

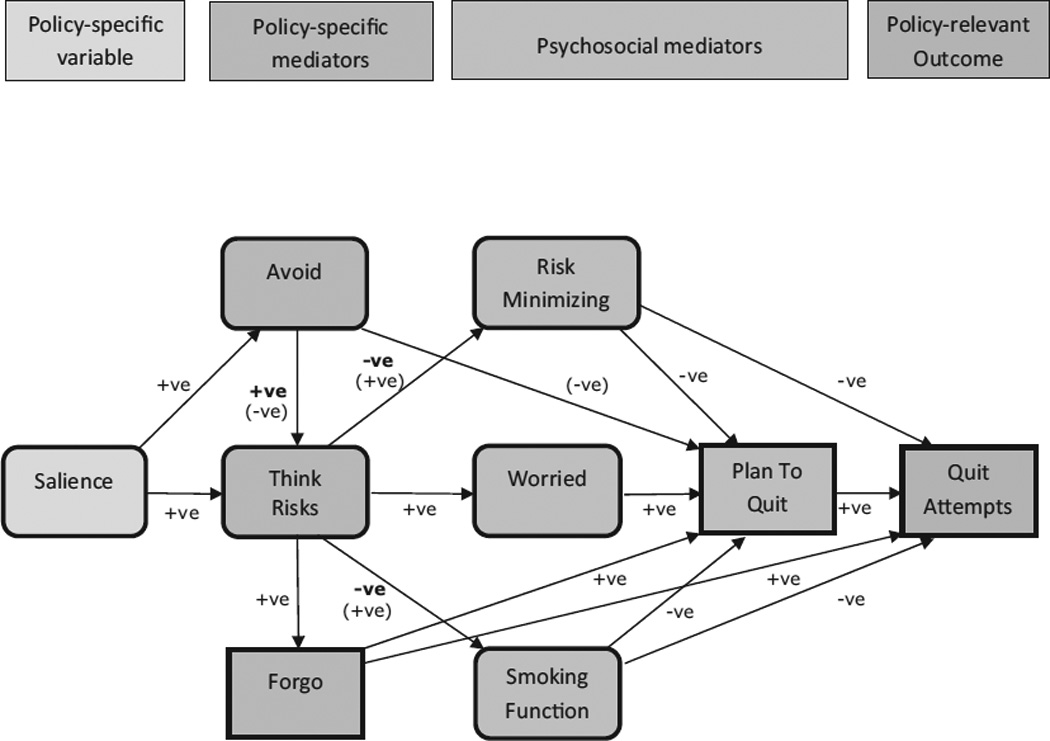

This paper extends previous regression-based work by Borland et al (2009) to explicitly test a mediational model of how warnings labels might impact smoking behavior. As illustrated in Figure 1, this model theorized that health warning labels are expected to influence individuals by first influencing factors that are most proximal to the policy itself such as noticing and reading the warning labels, and as a result, they act to influence the extent to which people think about the harms of smoking, which in turn raise their smoking-related health concerns, leading them to form intentions to quit, and eventually stop smoking altogether. This mediational model has been theorized in broad terms based on the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Conceptual Model of the effect of tobacco control policies on smoking behaviors (Fong et al., 2006; International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2008), but is expanded here to take into account possible impacts of cognitive and behavioural avoidance. The overall framework of the ITC model is that policies have immediate proximal impacts which subsequently affect more general mediators of quitting activity and through them affect quitting-related behaviour (Fong et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model of the pathways explaining the impact of warning labels. Note that this model is simplified version—the indicator variables for each latent construct, the associations among the mediators (forgo, avoid, worried, smoking function, and risk minimizing) along with the pathways of the control variables (country, age group, sex, education, and daily cigarette consumption) are not shown. Salience, think risks, avoid risk minimizing, worried, and smoking function are latent variables while forgo, plan to quit, and quit attempts are observed variables. The predicted effect of the positive influence model is in bold face whereas that of the reactance model is in parentheses, with the other effects being similar for the two models.

The extant literature suggests that there are two plausible competing models for the impact on quitting of warning labels. The positive influence model, developed from findings based on both population survey research (e.g., (Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009; Hammond et al., 2003)) and experimental studies (e.g., (Emery, Romer, Sheerin, KH, & Peters, 2013)), which predicts that reactions to the warnings will produce positive effects on quitting interest and activity, and that there will be no overall negative effects even from occasional avoidance of the warnings. By contrast, the reactance model, based on arguments drawn mainly from the fear appeals literature (e.g., (de Bruin & Peters, 2013; G. Peters, Ruiter, & Kok, 2012; Ruiter, Abraham, & Kok, 2001; Ruiter & Kok, 2005)), predicts that avoidance will be associated with reduced desirable responses to the warnings and that any strong reactions to the warnings will lead to counter-productive effects that will at least reduce their desirable effects.

To date, research evidence suggests that larger and graphic health warnings on cigarette packs are noticed more often, stimulate more harm- and quitting-related cognitive and behavioural responses, and increase knowledge of health effects of smoking better than relatively small text-only warnings (Cameron, Pepper, & Brewer, 2013; Hammond, 2011; Yong et al., 2013). Research evidence to date has also demonstrated that cognitive reactions to warning labels on cigarette packs such as thoughts about the harms of smoking stimulated by the warnings and behavioural reactions such as forgoing a planned cigarette are both strongly positively associated with quit intentions (Fathelrahman et al., 2009) and also both cognitive reactions and forgoing cigarettes independently and prospectively predict making quit attempts among adult smokers (Borland, 1997; Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009). Larger and graphic warnings have also been shown to result in greater avoidance behaviour (Borland, Wilson, et al., 2009; Hammond, Fong, McDonald, Cameron, & Brown, 2004) and these reactions are positively correlated with cognitive reactions, and subsequent quit attempts, although when controlling for cognitive reactions, they are no longer positively predictive of attempts. Studies to date have generally failed to find any adverse effects of avoidance behaviour on quitting interest and behaviour (Borland, Wilson, et al., 2009; Hammond et al., 2004; Kees, Burton, Andrews, & Kozup, 2010; E. Peters et al., 2007). Thus, the evidence is directly contrary to the contention by some that avoidance behaviour will lead to a reduction in desirable behaviour change (G. Peters et al., 2012; Ruiter et al., 2001; Ruiter & Kok, 2005) which is based on experimental studies typically of single exposures. It is plausible that on the occasions when a person avoids the health warnings, they may be less likely to take any action towards quitting. However, population-based survey data has shown that over a period of time these smokers will also be more likely to think about the warnings and thus, take quit-related action (Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009).

Turning to possible mediators of the effects of warning labels, both the positive influence and reactance models postulate that there are three types of mediators that are relevant. First are worries or concerns about health (Costello, Logel, Fong, Zanna, & McDonald, 2012; Emery et al., 2013; International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2008) which are theorised to increase people’s interest in quitting smoking. Second are functional beliefs about the utility of smoking (Yong & Borland, 2008), which should be negatively related to quitting activity. A positive effect of reactions to warnings would be to undermine functional beliefs, while a reactance effect would be to lead to an overvaluing of benefits as part justification for continuing to smoke. Third are risk minimising beliefs (Borland, Yong, Balmford, et al., 2009), which are a form of cognitive avoidance that smokers may engage in when confronted with strong health warnings. A positive influence model would predict that these beliefs would be reduced by strong health warnings, while a reactance model would predict that they would increase in reaction to the warnings. These psychological mediators have been shown in past studies to have a strong predictive effect on subsequent quitting intentions (Hammond et al., 2003; Kees et al., 2010; Romer, Peters, Strasser, & Langleben, 2013) and behaviour (Borland, Yong, Balmford, et al., 2009; Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009; Costello et al., 2012; Hammond et al., 2007; Hammond et al., 2003; Hyland et al., 2006; Shanahan & Elliot, 2009; Yong & Borland, 2008).

In order to ensure the effectiveness of warning labels, it is critically important to understand how and why warning labels work. Thus the key aims of this study were to test and develop a robust model of the impacts of health warnings on smoking behaviour and secondarily to test the competing positive influence versus reactance models of effect using data from the International Tobacco Control Four-Country Survey (ITC-4) conducted in four high-income English-speaking countries (Australia, Canada, UK, and the USA). Specifically, the aims were (a) to test the hypothesized pathways explaining the impact of warning labels on quitting behaviour of adult smokers; (b) to examine whether avoidance behaviour inhibits (reactance model) or facilitates (positive influence model) cognitive response to warning labels and motivation to quit smoking; (c) to examine whether harm-related thoughts stimulated by warning labels challenge and reduce risk-minimising beliefs and smoking function beliefs (positive influence model) or increase them (reactance model); and (d) to validate the model derived from the calibration sample using a new sample. Based on the positive influence model, it was hypothesized that health warning labels would stimulate quit attempts primarily by first stimulating smokers to think about the harms of smoking and in turn increasing their personal concerns about the future negative impact of smoking on health and quality of life, while decreasing their psychological defences and perceived value of smoking (both are known to undermine quitting), all of which would lead to increased intention to quit smoking, a key predictor of future quit attempts. Both models would predict that warning labels would positively influence the behaviour of forgoing a cigarette primarily through thoughts about harms of smoking and that forgoing behaviour in turn would lead to stronger quit intentions. Forgoing might also have a direct positive effect on subsequent quit attempts (Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009). Both models would also predict that warning labels would stimulate increased avoidance behaviour but a reactance model would predict that it would inhibit thoughts about smoking harms and motivation to quit smoking rather than having facilitating effects as predicted by a positive influence model.

At the time of the current study, warning labels across the four countries differed in size, content and nature (graphic versus text). Warnings ranged from the large Canadian graphic warning labels to the small US text-only warnings on the side of packs. Despite these differences, country differences in the mediational pathways were not expected as no by-country interaction was found in past research (Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009) suggesting that stronger warnings have their effect by eliciting stronger reactions rather than different kinds of effects. The analysis was also limited to quit attempts as the main outcome since factors associated with making quit attempts are quite different from those for quit maintenance (Borland et al., 2010; Vangeli, Stapleton, Smit, Borland, & West, 2011). This is confirmed by the fact that predictive effect of warning label effectiveness measures was found for quit attempts but not on quit success among those who tried (Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009) except when these measures were assessed post quitting (Partos, Borland, Yong, Thrasher, & Hammond, 2012).

METHODS

Sample and design

The study made use of two samples drawn from the ITC Four Country (ITC-4) Survey, a cohort study of adult smokers followed up annually with replenishment, conducted in Australia, Canada, UK and the US. The main aim of the ITC-4 project is to evaluate the psychosocial and behavioural effects of national-level tobacco control policies. Respondents were recruited in each country using stratified random-digit dialling and computer assisted telephone technique where households were contacted and screened for adult smokers with the next birthday who would agree to participate in the study. Those who agreed were rescheduled for a telephone survey a week later, and were sent a cheque or voucher to compensate for their time. The study protocol was cleared for ethics by the relevant Institutional Review Boards in the four countries studied. Further details of the methodology of the ITC-4 Survey have been reported elsewhere (Thompson et al., 2006).

Calibration sample

This consisted of adult current smokers who participated in Wave 5 of the ITC-4 Survey and who were successfully followed up at Wave 6, approximately a year later. This sample was called the calibration sample as it was used for testing the hypothesized mediational model and developing a good fitting model which was then validated on a second sample below, that is, the validation sample. The total respondents at baseline were 8243, but only 7038 were current smokers. Of these, 4988 (70.9%) were successfully followed up (mean length=335 days, SE=.56) and used for analysis.

Validation sample

Like the above, it consisted of adult current smokers who participated in the survey at Wave 6 and were successfully followed up at Wave 7. The total at baseline was 8194, of which 6886 were current smokers and of these, 5065 (76.3%) were successfully followed up (mean length=394 days, SE=.70).

For the purpose of this study, the policy-specific variable, policy-specific mediators and psychosocial mediators used for calibration and validation were based on survey data from Wave 5 (collected from September 2006 to February 2007) and Wave 6 (collected from October 2007 to January 2008), respectively while the policy-relevant outcome was based on Wave 6 and Wave 7 data (collected between October 2008 and March 2009), respectively.

Measures

The measures used in measurement and structural models for both calibration and validation are presented in Table 1. They have been specifically chosen or developed for inclusion in the ITC survey based on their reliability and validity as measures of the respective constructs of interest (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2008). For some analytic purposes (t-tests and correlations), questions assessing the same constructs were combined by averaging their responses except for Avoidance to form composite measures with scale reliability as shown in Table 1. As per previous research (Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009), an index of avoidance was created by summing the responses across the four kinds of avoidance behaviour (i.e., covering up the warnings, keeping them out of sight, using a cigarette case, and not buying packs with certain labels). For modelling, the policy-specific variable was warning label salience, modelled as a latent variable with two indicator items. The policy-specific mediators consisted of one cognitive (i.e., Think risks) and two behavioural variables (i.e., Avoid and Forgo). Think risks was modelled as a latent variable with three indicators. Behavioural avoidance was modelled as a latent variable with four indicators for calibration purposes but as an observed variable for validation because it was only assessed using a single question in Wave 6 to reduce respondents’ burden. There were four psychosocial mediators in the model, namely, Risk-minimising beliefs, Worried about smoking harms, Smoking functions (all three modelled as latent variables with multiple indicators) and Intentions to quit (measured using a single question and modelled as an observed variable). The policy-relevant outcome was any quit attempts since the previous wave, assessed at follow-up using a single question. Control variables were country, gender, age group, education levels (using 3 categories to roughly equate the different education systems across the four countries) and number of cigarettes smoked per day (CPD), all modelled as observed variables.

Table 1.

Observed and latent variables used in the measurement and structural models for calibration and validation samples.

| Measures | Indicator item wording | Factor loading |

|---|---|---|

| Latent variables | ||

|

Salience Cronbach’s alpha=.67 (.79) |

In the last month, how often, if at all, have you noticed the warning labels on cigarette packages? – Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Very often; In the last month, how often, if at all, have you read or looked closely at the warning labels on cigarette packages? – Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Very often |

.83 (.83) .72 (.73) |

|

Think risks Cronbach’s alpha=.79 (.79) |

To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking? -- Not at all, A little, Somewhat, A lot; To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking? -- Not at all, A little, Somewhat, A lot; In the past 6 months, have [warning labels on cigarette packages] led you to think about quitting? -- Not at all, Somewhat, Very much |

.90 (.87) .84 (.86) .76 (.80) |

|

Worried Cronbach’s alpha=.84 (.84) |

How worried are you, if at all, that smoking will damage your health in the future? -- Not at all worried, A little worried, Moderately worried, Very worried; How worried are you, if at all, that smoking will lower your quality of life in the future? -- Not at all worried, A little worried, Moderately worried, Very worried |

.94 (.93) .86 (.86) |

| Avoid1 | In the last month, have you made any effort to avoid looking at or thinking about the warning labels … By covering the warnings up? -- Yes, No; By keeping the pack out of sight? -- Yes, No; By using a cigarette case or some other pack? -- Yes, No; By not buying packs with particular labels? -- Yes, No |

.92 (NA) .93 (NA) .78 (NA) .64 (NA) |

|

Risk-minimising beliefs Cronbach’s alpha=.67 (.67) |

Please tell me whether you strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree with each of the following statements: The medical evidence that smoking is harmful is exaggerated; You've got to die of something, so why not enjoy yourself and smoke; Smoking is no more risky than lots of other things that people do. |

.52 (.53) .76 (.75) .62 (.64) |

|

Smoking function beliefs Cronbach’s alpha=.53 (.42) |

Please tell me whether you strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree with each of the following statements: You enjoy smoking too much to give it up; Smoking is an important part of your life. |

.66 (.49) .55 (.54) |

| Observed variables | ||

| Forgo | In the last month, have the warning labels stopped you from having a cigarette when you were about to smoke one? – Never, Once, A few times, Many times | NA |

| Avoid2 | In the last month have you made any effort to avoid looking at or thinking about the warning labels such as covering them up, keeping them out of sight, using a cigarette case, avoiding certain warnings, or any other means? – Yes, No | NA |

| Plan to quit | Are you planning to quit smoking --within the next month, within the next 6 months, sometime in the future beyond 6 months, or are you not planning to quit? | NA |

| Making quit attempts | Have you made any attempts to stop smoking since we last talked with you in [last survey date]? -- Yes, No | NA |

NB.

NA, not applicable;

“You enjoy smoking too much to give it up” cross-loaded on the latent variable “Worried” with standardised factor loading of −.25 and −.21 for calibration and validation models, respectively;

Figures in parentheses are for validation model;

Avoid1, multiple-item question was used to assess avoidance behaviour in Wave 5; Avoid2, single-item question used instead in Wave 6;

Data analysis

Calibration analysis

Analyses of sample attrition and sample characteristics, along with correlation among variables were conducted using Stata version 12. For practical reasons, all variables were treated as continuous measures for the correlational analyses.

Structural equation modeling of the proposed mediational pathways of warning impact (see Figure 1) was conducted using Mplus version 6. For modelling data from both continuous and categorical measures, parameter estimation was based on weighted least squares with mean and variance adjusted chi-square test statistic (Asparouhov, 2005). Models were estimated as follows: First, we estimated a measurement model that included all latent variables with multiple indicators in the hypothesized model (i.e., warning label salience, thoughts about smoking risks and about quitting as a result of warning labels, worry about future damage to health and quality of life, avoidance of warning labels [calibration model only], risk-minimising beliefs, and functional beliefs about smoking). Next, we estimated the structural model, which included both latent and observed variables, and involved testing prospective effects of individual attention to health warning labels on making quit attempts through both policy-specific mediators and psychosocial mediators. Indicators of risk-minimising beliefs and functional beliefs about smoking had approximately normal distributions and thus were treated as continuous variables; all other measures were treated as categorical variables and had non-normal distributions. In the structural models, we controlled for country, age, gender and CPD by regressing all variables on them.

The adequacy of overall model fit was evaluated using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; (Bentler, 1990)), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; (Browne & Cudeck, 1993)). Acceptable model fit is indicated by a value of greater than .95 on both CFI and TLI (Hu & Bentler, 1999), and a value less than .05 on the RMSEA. Where appropriate, modification indices were employed to help suggest revision to the model to improve model fit. The Mplus command difftest was used to compare nested models to help decide if a given model fits significantly better or worse than a competing model (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2010).

All analyses used survey weights constructed to make the sample representative of the smoker population in geographic regions of each of the four countries, and calibrated by age and gender (Thompson et al., 2006).

Validation analysis

This involved the same kind of analyses and model fit evaluation as that conducted for the calibration except that instead of testing the hypothesized models, the finalised measurement and structural models from the calibration analyses were tested on Waves 6–7 sample to determine the robustness of the results.

Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the hypothesized model using Waves 5–6 subsamples derived from random split-half and separate country data. We also conducted mediational analysis to test the significance of the indirect paths of warning label salience via the hypothesized mediating variables to quit attempts.

RESULTS

Calibration model

Sample characteristics and attrition

Sample characteristics by attrition status are presented in Table 2. Retained respondents were older (p<.001), more likely to come from Australia, to endorse functional beliefs about smoking (p<.001) but less likely to forgo a cigarette because of warning labels (p<.01) than those lost to the study. The two groups were similar on all other measures.

Table 2.

Characteristics of calibration and validation samples by attrition status.

| Calibration (Waves 5–6) |

Validation (Waves 6–7) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retained N=4988 |

Lost N=2050 |

Group difference |

Retained N=5065 |

Lost N=1821 |

Group difference |

|

| Control variables (baseline wave) | ||||||

| Country (%) | ||||||

| Canada | 24.9 | 24.2 | P<.001 | 25.7 | 22.2 | P<.001 |

| USA | 22.7 | 32.2 | 23.7 | 29.9 | ||

| UK | 25.3 | 21.6 | 23.6 | 24.5 | ||

| Australia | 27.1 | 22.0 | 26.9 | 23.3 | ||

| Gender − Male (%) | 42.5 | 42.8 | P=.84 | 42.8 | 42.7 | P=.94 |

| Age group (%) | ||||||

| 18–24 | 5.6 | 11.6 | P<.001 | 4.2 | 10.9 | P<.001 |

| 25–39 | 24.2 | 32.9 | 22.7 | 31.8 | ||

| 40–54 | 42.1 | 35.8 | 43.2 | 34.4 | ||

| 55+ | 28.1 | 19.7 | 29.9 | 22.8 | ||

| Education levels (%) | ||||||

| Low | 52.2 | 55.6 | P=.03 | 51.3 | 52.9 | P=.46 |

| Medium | 31.1 | 29.3 | 31.4 | 30.6 | ||

| High | 16.7 | 15.1 | 17.3 | 16.5 | ||

| Cigarettes per day − M (SE) | 17.3 (.14) | 17.2 (.24) | P=.77 | 17.3 (.14) | 16.9 (.24) | P=.16 |

| Policy-specific variables (baseline) | ||||||

| Salience − M (SE)a | 3.3 (.02) | 3.4 (.03) | P=.21 | 2.8 (.02) | 2.9 (.03) | P=.33 |

| Policy-specific mediators (baseline) | ||||||

| Thoughts re risks of smoking−M (SE)b | 2.0 (.01) | 2.0 (.02) | P=.51 | 1.7 (.01) | 1.8 (.02) | P<.01 |

| Avoidance − M (SE)c / % Yesd | 0.4 (.01) | 0.4 (.02) | P=.95 | 13.3 | 14.7 | P=.13 |

| Forgo − M (SE)b | 1.2 (.01) | 1.3 (.02) | P<.01 | 1.2 (.01) | 1.3 (.02) | P<.001 |

| Psychosocial mediators (baseline) | ||||||

| Worried re damage from smoking | ||||||

| −M (SE)b | 2.6 (.01) | 2.6 (.02) | P=.54 | 2.5 (.01) | 2.5 (.02) | P=.14 |

| Risk-minimising beliefs | ||||||

| − M (SE)a | 3.0 (.01) | 3.0 (.02) | P=.14 | 2.9 (.01) | 2.9 (.02) | P=.44 |

| Smoking function beliefs | ||||||

| − M (SE)a | 3.2 (.01) | 3.1 (.02) | P<.001 | 3.6 (.01) | 3.6 (.02) | P=.05 |

| Intention to quit (%) | ||||||

| Within the next month | 10.8 | 12.9 | P=.08 | 10.8 | 11.6 | P=.74 |

| Within the next 6 months | 23.9 | 24.1 | 22.1 | 22.5 | ||

| Sometime in the future, beyond 6 months | 35.4 | 34.2 | 36.1 | 35.4 | ||

| Not planning to quit | 29.9 | 28.7 | 31 | 30.4 | ||

| Policy-relevant outcome (follow-up) | ||||||

| Making quit attempts (%) | 37.3 | -- | -- | 38.5 | -- | -- |

NB.

M, mean; SE, standard error; -- not applicable

On a scale from 1 to 5;

On a scale from 1 to 4;

On a scale from 0 to 4;

percent based on a Yes-No response for the single item measure for validation;

Correlations

Correlations between policy-specific variables, policy-specific mediators, psychosocial mediators and policy-relevant outcome are presented in Table 3. Warning label salience was most strongly and positively related to thoughts about the risks of smoking followed by forgoing. Think Risks was most strongly and positively associated with Forgo followed by Worried. However, Think Risks was negatively correlated with Risk-minimising and Smoking Function. Worried was most strongly and negatively associated with Risk-minimising beliefs but positively associated with quit intentions. Risk-minimising and Smoking Function correlated negatively with both quit intentions and quit attempts. Quit attempts correlated most strongly and positively with quit intentions.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation matrix between policy-specific variable, policy-specific mediators, psychosocial mediators and policy-relevant outcome for calibration and validation samples.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration | |||||||||

| 1.Salience | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2.Think risks | 0.41*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3.Worried | 0.16*** | 0.39*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4.Avoid | 0.12*** | 0.25*** | 0.11*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 5.Forgo | 0.25*** | 0.44*** | 0.17*** | 0.20*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 6.Risk-minimising | −0.10*** | −0.30*** | −0.46*** | −0.05** | −0.14*** | 1.00 | |||

| 7.Smoking function | −0.09*** | −0.18*** | −0.15*** | −0.01 | −0.14*** | 0.31*** | 1.00 | ||

| 8.Plan to quit | 0.10*** | 0.32*** | 0.42*** | 0.08*** | 0.18*** | −0.37*** | −0.34*** | 1.00 | |

| 9.Quit attempts | 0.08*** | 0.17*** | 0.19*** | 0.05** | 0.14*** | −0.17*** | −0.19*** | 0.36*** | 1.00 |

| Validation | |||||||||

| 1.Salience | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2.Think risks | 0.47*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3.Worried | 0.16*** | 0.40*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4.Avoid | 0.14*** | 0.25*** | 0.11*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 5.Forgo | 0.26*** | 0.42*** | 0.15*** | 0.18*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 6.Risk- minimising | −0.11*** | −0.29*** | −0.49*** | −0.05*** | −0.09*** | 1.00 | |||

| 7.Smoking function | −0.10*** | −0.17*** | −0.09*** | −0.01 | −0.13*** | 0.20*** | 1.00 | ||

| 8.Plan to quit | 0.10*** | 0.29*** | 0.42*** | 0.07*** | 0.14*** | −0.35*** | −0.23*** | 1.00 | |

| 9.Quit attempts | 0.05** | 0.16*** | 0.22*** | 0.06*** | 0.12*** | −0.18*** | −0.14*** | 0.37*** | 1.00 |

NB.

p<.01;

p<.001;

Structural Equation Models (SEM)

Measurement model

The results indicated that the model was a good fit to the data (CFI=0.987; TLI=.982; RMSEA=0.027) but the item “You enjoy smoking too much to give it up” had a negative residual variance. Based on the modification index, this could be resolved by allowing this item to cross-load on the latent variable “Worried” which is substantively meaningful as enjoyment can be considered an indicator of worry but phrased positively. The fit of the revised model was significantly improved (chi-square difference test=46.4, df=1, p<.001; CFI=0.989; TLI=.985; RMSEA=0.025). Factor loadings of the indicators for each latent variable in the final model were all significant at p<.001, with standardized values ranging between .52 and .94 (see Table 1). The cross-loading item has a factor loading of −.25, p<.001.

Structural model

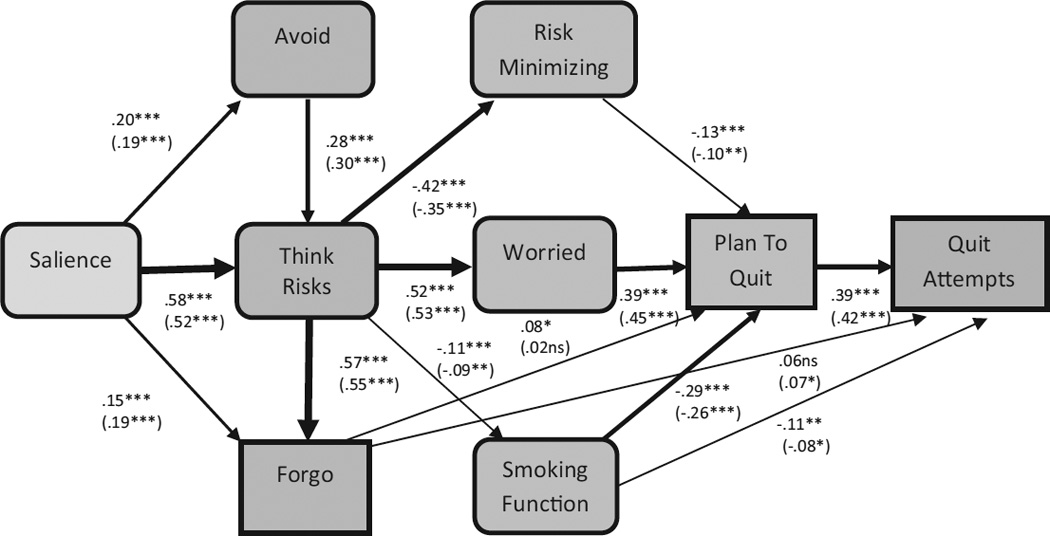

The hypothesized model as depicted in Figure 1 was a good fit to the data (CFI=0.978; TLI=.966; RMSEA=0.027) but could be further improved by adding a direct path from Salience to Forgo (chi-square difference test=15.4, df=1, p<.001). The revised model still exhibited good overall fit to the data (CFI=0.978; TLI=.966; RMSEA=0.027) and explained 23% of the variance in quit attempts (see Figure 2 and also Supplementary Table 1 for details). As hypothesized, warning label salience was positively associated with thoughts about risks of smoking and about quitting (β=.58, p<.001). Label salience was also positively associated with the two behavioural reactions to the warnings, namely, avoidance behaviour (β=.20, p<.001) and forgoing a cigarette (β=.15, p<.001). Avoidance, however, had a positive association with thoughts about risks and about quitting (β=.28, p<.001), contrary to the prediction of the reactance model. As expected from both models, thoughts about risks and quitting predicted increased worry about smoking doing damage to health and lowering quality of life (β=.52, p<.001), and worry in turn predicted stronger intention to quit smoking (β=.39, p<.001). Thoughts about risks and about quitting stimulated by warning labels were also found to strongly predict frequency of forgoing a cigarette (β=.57, p<.001). Forgoing, however, was only a weak predictor of both quit intention (β=.08, p<.05) and quit attempts (β=.06, p=.068). Contrary to the prediction of the reactance model but consistent with the positive influence model, thoughts about risks and about quitting were negatively associated with risk-minimising beliefs (β=−.42, p<.001) and smoking function beliefs (β=−.11, p<.01); however, as expected, both kinds of beliefs were negatively associated with quit intention (β=−.13 and −.29, both p’s<.001). As predicted, smoking function also had a direct negative effect on quit attempts (β=−.11, p<.001). Again as expected, quit intention was a strong predictor of making quit attempts subsequently (β=.39, p<.001).

Figure 2.

Structural equation model for Waves 5–6 calibration sample and Waves 6–7 validation sample with standardized regression coefficients (validation in parentheses) assessing the pathways of warning label impact on making quit attempts. To simplify presentation, control variables, factor loadings, residual values, regression coefficients of nonsignificant paths, and associations between variables were omitted from the figure. The thickness of the arrow depicts the effect size. ns = not statistically significant. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Validation model

The results from the validation analysis were very similar to that of the calibration analysis (see Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1 for details). Both the measurement and the structural models were a good fit to the Waves 6–7 data (CFI=.993 and .985; TLI=.989 and .973; RMSEA=.026 and .027, respectively). All pathways were successfully replicated with very similar effect sizes except for the direct path from Forgo to Plan to quit which was not significant (β=.02, p=.468). Results from random split half and separate country analyses were also very similar to that of the calibration analysis with only minor exceptions where effects for some pathways were either marginally significant or not significant at all but still trending in the same direction (see Supplementary Table 1).

Tests of indirect paths

Results indicated that the tested indirect effects of warning label salience on quit attempts were all statistically significant for both the calibration and validation models with one exception (see Table 4). The indirect path via Forgo, however, was not significant in the validation model (β=.002, p=.469).

Table 4.

Indirect effects of warning label salience on making quit attempts.

| Indirect effects | W5–6 Calibration | W6–7 Validation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | se | Beta | se | |

| Salience → Quit attempts | ||||

| via Think risks, Worried, & Plan to quit | .049*** | 0.006 | .040*** | 0.006 |

| via Think risks, Forgo, & Plan to quit | .010* | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| via Think risks, Smoking function, & Plan to quit | .008*** | 0.002 | .004** | 0.002 |

| via Think risks, Risk Minimising, & Plan to quit | .013** | 0.004 | .006* | 0.003 |

NB.

Beta=standardised regression coefficients; se=standard error;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001;

DISCUSSION

Main findings

The results from this study demonstrate that the hypothesized mediational model of health warning label impact provided a good fit to the data both individually and pooled across the four countries studied, thus supporting the broad ITC Conceptual Model, which hypothesized that policies influence attempts to stop smoking through policy-specific variables and psychosocial mediators. These analyses are a demonstration, similar to Nagelhout et al.’s (2012), of the usefulness of the longitudinal cohort design of the ITC Project Surveys, coupled with the inclusion of multiple indicators of policy impact—allowing analytic models of considerable richness to be employed to answer questions about how policies may ultimately have an impact on important behaviours such as cigarette reduction, quit attempts, and quit success.

The findings from the present study confirm our hypothesis that warning labels are effective in changing smokers’ behaviour primarily by stimulating them to think about the risks of smoking, which in turn evoke emotional reactions of worrying about negative outcomes, such as future health consequences and lowered quality of life from smoking. The increase in health concerns from the negative impact of smoking then appears to increase intentions to quit smoking, which stimulates quitting behaviour. The consistency of the findings across the four countries suggests that despite the diverse warning labels across these countries with stronger warnings producing greater levels of reactions as found previously (Borland, Wilson, et al., 2009; Hammond et al., 2007), once people are engaged by the warning labels regardless of their nature/type, the same processes are involved in carrying through their impacts on quitting behaviour. The small text-only warnings in the US are less noticeable and hence, very few people pay any attention to these warnings and those who do (for whatever reasons), are influenced in similar ways resulting in a similar behavioural change. So larger and graphic warnings are more effective in the sense of being able to draw more people to pay attention to and engage with these warnings (Borland, Wilson, et al., 2009; Hammond, 2011).

The finding of the important role of thoughts about the risks of smoking in the hypothesized mediational pathway is consistent with the independent predictive effect of this same cognitive factor found by Borland et al (2009) using logistic regression models. The data reveal that this cognitive response to warning labels brings about the desired quitting behaviour primarily by enhancing the downstream affective, motivational and behavioural facilitators of such behaviour and reducing the psychological barriers to quitting. Inherent in the positive influence model is the expectation that the extent of thinking about smoking harms is predicated on being informed about the health risks of smoking, initially through new warning label content improving smokers’ knowledge of a wide range of health effects of smoking and subsequently through constantly reminding them of the health effects triggered by each exposure of the warning labels. Relatively larger and more graphic warning labels that are more salient have been shown to do a better job at this (Hammond, 2011; Hammond et al., 2012; Thrasher, Arillo-Santillán, et al., 2012; Thrasher, Carpenter, et al., 2012; Thrasher, Pérez-Hernández, Arillo-Santillán, & Barrientos-Gutierrez, 2012).

As expected from both models, warning labels that are salient stimulate avoidance behaviour, but contrary to the prediction of the reactance model (de Bruin & Peters, 2013; G. Peters et al., 2012; Ruiter & Kok, 2005), such behaviour inhibits neither thoughts about the harms of smoking nor motivation to quit smoking, lending further support to previous finding of no adverse effects of avoidance behaviour from several experimental (Kees et al., 2010; E. Peters et al., 2007) and population-based studies (Borland, Yong, Wilson, et al., 2009; Hammond et al., 2004). The data presented in this paper show that behavioural avoidance was associated with increased rather than decreased frequency of thoughts about smoking harms, suggesting another pathway through which warnings can exert their influence on subsequent quitting behaviour. This is not surprising as any attempts to avoid the warnings so as to not think of the harms of smoking prove futile. The more one tries to not think of something, the more one tends to focus on it (Rassin, Merckelbach, & Muris, 2000; Wegner, 1994). These findings suggest that at least at the population level where smokers are repeatedly exposed to warning messages over a period of time, avoidance of warnings does not appear to have any adverse effects as predicted by some. The lack of adverse outcomes even in countries like Canada and Australia that have strong warnings might be because these warnings are accompanied by telephone quitline number and/or other supportive messages designed to increase self-efficacy for quitting. Some health communication theories predict that messages that combine threatening information with information that increase self-efficacy for behaviour change are more likely to result in positive behaviour change (Witte & Allen, 2000).

Again as predicted by both models, salient warnings can also lead smokers to momentarily resist and forgo a planned cigarette. Such immediate cessation-related behaviour is stimulated mainly by thoughts about the harms of smoking although there is some evidence that it can also be directly triggered by warnings that are salient. Consistent with Borland et al.’s (2009) finding, forgoing behaviour leads smokers to subsequently make a quit attempt either directly or via quit intentions although neither pathway seems robust. Future research is warranted to clarify whether the immediate non-smoking actions stimulated by warning labels influence downstream quitting behaviour directly or indirectly via quitting motivation.

The analyses also indicate that another route whereby thoughts stimulated by warning label can stimulate subsequent quitting activity is by challenging and reducing beliefs that serve as psychological rationalizations and justifications for smoking. Consistent with past research (Borland, Yong, Balmford, et al., 2009; Yong & Borland, 2008), both of these beliefs have an inhibiting effect on motivation to quit smoking with functional beliefs about smoking also having a direct inhibiting effect on quit attempts. However, the data in this paper suggest that warning-label-stimulated thoughts about the harms of smoking do not increase these beliefs as predicted by the reactance model but rather consistent with the positive influence model, they lead to a reduction in both of these beliefs, which reduces their overall negative impact on quit intentions and behaviour.

Strengths & limitations

This study has several strengths. First, as far as we are aware, this is the first study to examine a full, theoretically based mediational model explaining the effect of cigarette pack warning labels on quitting behaviour. Second, the large sample size, the longitudinal design, the validation of the model on different samples and the consistency of the findings across countries provide confidence in the robustness of the final model. However, several study limitations warrant a mention. First, it might be argued that the findings presented here are based on four high-income countries and may not fully generalise to other countries with different cultural and socio-economic environments. However, it should be noted that the hypothesized model was tested on data pooled across four countries with warning labels that differ in nature, size and position and any country-specific effect was controlled for, and the fact that it was successfully replicated provides confidence that the effect of warning label impact will be mediated through similar pathways in many other countries as well. Second, the mediators were all collected at the same time point although the fact that our model was successfully replicated in different samples does lend support to the credibility of the causal assumptions made in our model. Third, it is possible that there might be other alternative models that had not been tested that would fit the data equally well, or even better.

Findings Implications

The findings here have important implications for health warning policy implementation and development. It is now clear that larger and more graphic warnings are better at getting more people to pay attention to them (Borland, Wilson, et al., 2009; Hammond, 2011; Hammond et al., 2007; Hammond et al., 2003; Thrasher, Pérez-Hernández, et al., 2012) and once people are engaged, warnings will have a chance to change behaviour via various pathways of influence. Therefore, efforts should be made by policy-makers to increase the salience of warning labels through the use of elements such as pictorial images, changing graphic design elements, increasing the size of warnings particularly on front of packs, and putting warnings against a standardised background like the plain packaging introduced in Australia recently. Other interventions such as the use of mass media campaigns that carry similar health warnings and also the display of similar warnings at point of sale may complement the pack warnings as these strategies can help to reinforce the same messages found on cigarette pack warning labels (Brennan, Durkin, Cotter, Harper, & Wakefield, 2011; Coady et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012; Thrasher et al., 2013). From an implementation perspective, to ensure that warning labels remain highly salient, they should be placed prominently at the front of tobacco products, and refreshed periodically to overcome habituation. Challenging smokers’ beliefs about the functional utility of smoking and helping them to find healthy alternatives may also help reduce the psychological barrier to quitting.

Conclusions

The study findings support a simplified conceptual model of the impact of warning labels as follows. Cigarette warning labels seem to encourage smokers to quit smoking through the main pathway of getting them to pay attention to these warnings, then by stimulating them to think about the harms of smoking which help to raise their concerns for the future negative outcomes of smoking. This, in turn, leads to stronger intentions to quit smoking, which then drives them to try to change their behaviour. A second pathway is through generating harm-related thoughts that counteract and reduce psychological defences and a third by weakening beliefs about the value of smoking. There may be a fourth, of thoughts leading to forgoing cigarettes which may have a small independent effect, but whether through intentions or directly through to attempts is unclear. Avoidance behaviour shows no undesirable effect and only has any effect it may have through increasing (not decreasing) the frequency of thoughts about smoking harms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Gang Meng and Celia Huang for their suggestions and help with data analysis.

Funding: The ITC Four-Country Survey is supported by multiple grants including R01 CA 100362 and P50 CA111236 (Roswell Park Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center) and also in part from grant P01 CA138389 (Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, New York), all funded by the National Cancer Institute of the United States, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (045734), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (57897, 79551), National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (265903, 450110, APP1005922), Cancer Research UK (C312/A3726), Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative (014578); Centre for Behavioural Research and Program Evaluation, National Cancer Institute of Canada/Canadian Cancer Society. The work was also supported by the UICC International Cancer Technology Transfer fellowship to HHY undertaken at the University of Waterloo.

REFERENCES

- Asparouhov T. Sampling weights in latent variable modelling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2005;12(3):411–434. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R. Tobacco health warnings and smoking-related cognitions and behaviours. Addiction. 1997;92(11):1427–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT, Hammond D, Cummings KM, Yong HH, et al. Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: Findings from four countries over five years. Tobacco Control. 2009;18:358–364. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Yong H, Balmford J, Cooper J, Cummings K, O’Connor R, et al. Motivational factors predict quit attempts but not maintenance of smoking cessation: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four country project. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12(Suppl 1):S4–S11. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Yong H, Balmford J, Fong G, Zanna M, Hastings G. Do risk-minimizing beliefs about smoking inhibit quitting? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Survey. Preventive Medicine. 2009;49:219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.015. doi: org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Yong HH, Wilson N, Fong GT, Hastings G, Cummings KM, et al. How reactions to cigarette pack health warnings influence quitting: findings from the ITC Four Country survey. Addiction. 2009;104:669–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan E, Durkin S, Cotter T, Harper T, Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns designed to support new pictorial health warnings on cigarette packets: evidence of a complementary relationship. Tobacco Control. 2011;20(6):412–418. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.039321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne M, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen K, Long J, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron L, Pepper J, Brewer N. Responses of young adults to graphic warning labels for cigarette packages. Tobacco Control. 2013 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coady M, Chan C, Auer K, Farley S, Kilgore E, Kansagra S. Awareness and impact of New York City's graphic point-of-sale tobacco health warning signs. Tobacco Control. 2012 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello M, Logel C, Fong GT, Zanna M, McDonald PW. Perceived risk and quitting behaviors: results from the ITC 4-Country survey. American Journal of Health Behaviors. 2012;36(5):681–692. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.5.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin M, Peters G. Let's not further obscure the debate about fear appeal messages for smokers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(5):e51. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery L, Romer D, Sheerin K, KH J, Peters E. Affective and cognitive mediators of the impact of cigarette warning labels. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathelrahman A, Omar M, Awang R, Borland R, Fong GT, Hastings G, et al. Smokers’ responses towards cigarette pack warning labels in predicting quit intention, stage of change, and self-efficacy. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11:248–253. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, Hastings G, Hyland A, Giovino GA, et al. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(Suppl III):iii3–iii11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tobacco Control. 2011;20(5):327–337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, Cummings KM, McNeil A, Driezen P. Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, Cameron R, Brown KS. The impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:391–395. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, Cameron R, Brown KS. Graphic Canadian warning labels and adverse outcomes: Evidence from Canadian smokers. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1442–1445. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D, Thrasher J, Reid J, Driezen P, Boudreau C, Arillo-Santillán E. Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings among Mexican youth and adults: a population-level intervention with potential to reduce tobacco-related inequities. Cancer Causes and Control. 2012;23:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9902-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q, Yong HH, McNeil A, Fong GT, et al. Individual-level predictors of cessation behaviors among participants in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four country Survey. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:iii83–iii94. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, editor. Methods for Evaluating Tobacco Control Policies. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kees J, Burton S, Andrews J, Kozup J. Understanding how graphic pictorial warnings work on cigarette packaging. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 2010;29(2):265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Borland R, Yong HH, Hitchman SC, Wakefield M, Kasza K, et al. The association between exposure to point-of-sale anti-smoking warnings and smokers' interest in quitting and quit attempts: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2012;107:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus user's guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhout G, de Vries H, Fong G, Candel M, Thrasher J, den Putte B, et al. Pathways of change explaining the effect of smoke-free legislation on smoking cessation in the Netherlands: An application of the International Tobacco Control Conceptual Model. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2012;14(12):1474–1482. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partos T, Borland R, Yong H, Thrasher J, Hammond D. Cigarette packet warning labels can help prevent relapse: Findings from the International Tobacco Control 4-country policy evaluation cohort study. Tobacco Control. 2012 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E, Romer D, Slovic P, Jamieson K, Wharfield L, Mertz C, et al. The impact and acceptability of Canadian-style cigarette warning labels among US smokers and non-smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2007;9(4):473–481. doi: 10.1080/14622200701239639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters G, Ruiter R, Kok G. Threatening communication: A critical re-analysis and revised meta-analytic test of fear appeal theory. Health Psychology Review. 2012;7(Supplement 1):S8–S31. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2012.703527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassin E, Merckelbach H, Muris P. Paradoxical and less paradoxical effects of thought suppression: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(8):973–995. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Peters E, Strasser A, Langleben D. Desire versus efficacy in smokers’ paradoxical reactions to pictorial health warnings for cigarettes. PloS One. 2013;8:e54937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiter R, Abraham C, Kok G. Scary warnings and rational precautions: a review of the psychology of fear appeals. Psychology & Health. 2001;16:613–630. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiter R, Kok G. Saying is not (always) doing: cigarette warning labels are useless [letter] Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:329. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan P, Elliot D. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the graphic health warnings on tobacco product packaging 2008. Canberra: Australian government Department of Health & Ageing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson ME, Fong GT, Hastings G, Boudreau C, Driezen P, Hyland A, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(Suppl III):iii12–iii18. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher J, Arillo-Santillán E, Villalobos V, Pérez-Hernández R, Hammond D, Carter J, et al. Can pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages address smoking-related health disparities? Field experiments in Mexico to assess pictorial warning label content. Cancer Causes and Control. 2012;23:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9899-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher J, Carpenter M, Andrews J, Gray K, Alberg A, Navarro A, et al. Cigarette warning label policy alternatives and smoking-related health disparities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(6):590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher J, Murukutla N, Pérez-Hernández R, Alday J, Arillo-Santillán E, Cedillo C, et al. Linking mass media campaigns to pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages: A cross-sectional study to evaluate impacts among Mexican smokers. Tobacco Control. 2013;22:e57–e65. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher J, Pérez-Hernández R, Arillo-Santillán E, Barrientos-Gutierrez I. Towards informed tobacco consumption in Mexico: Effects of pictorial warning labels among smokers. Revista de Salud Pública de México. 2012;54:242–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit E, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106:2110–2121. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner D. Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review. 1994;101:34–52. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behaviour. 2000;27:591–615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong H, Borland R. Functional beliefs about smoking and quitting activity among adult smokers in four countries: findings from the ITC 4-Country Survey. Health Psychology. 2008;27(Supplement 3):S216–S223. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3(suppl.).s216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong H, Fong G, Driezen P, Borland R, Quah A, Sirirassamee B, et al. Adult smokers’ reactions to pictorial health warnings labels on cigarette packs in Thailand and moderating effects of type of cigarette smoked: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia (ITC-SEA) Survey. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.