Abstract

To meet the need of a large quantity of hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (CM) for pre-clinical and clinical studies, a robust and scalable differentiation system for CM production is essential. With an hPSC aggregate suspension culture system we established previously, we developed a matrix-free, scalable, and GMP-compliant process for directing hPSC differentiation to CM in suspension culture by modulating Wnt pathways with small molecules. By optimizing critical process parameters including: cell aggregate size, small molecule concentrations, induction timing, and agitation rate, we were able to consistently differentiate hPSCs to >90% CM purity with an average yield of 1.5 to 2×109 CM/L at scales up to 1L spinner flasks. CM generated from the suspension culture displayed typical genetic, morphological, and electrophysiological cardiac cell characteristics. This suspension culture system allows seamless transition from hPSC expansion to CM differentiation in a continuous suspension culture. It not only provides a cost and labor effective scalable process for large scale CM production, but also provides a bioreactor prototype for automation of cell manufacturing, which will accelerate the advance of hPSCs research towards therapeutic applications.

Keywords: human pluripotent stem cells, cardiomyocyte differentiation, suspension cell cultures, GMP

Introduction

Myocardial infarction and heart failure are leading causes of death worldwide. As the myocardium has a very limited regenerative capacity, endogenous cell regeneration cannot adequately compensate for heart damage caused by myocardial infarction. The concept of cell replacement therapy is an appealing approach to the treatment of these cardiac diseases. Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) are an attractive cell source for cell replacement therapies because they can be expanded indefinitely in culture and efficiently differentiated into a variety of cell lineages, including cardiac cells. However, current hPSC expansion and differentiation methods rely on adherent cell culture systems that are challenging to scale up to the levels required to support pre-clinical and clinical studies.

Activin/Nodal/TGF-β, BMP, and Wnt signaling play pivotal roles in regulating mesoderm and cardiac specification during embryo development1–7. Significant progress has been made in cardiac differentiation process by modulating Activin, BMP, and Wnt pathways, which can efficiently drive differentiation to over 80% purity of CM8–13. Using an adherent cell culture platform, one study revealed that using 2 small Wnt pathway modulators to sequentially activate and then inhibit Wnt signaling at different differentiation stages of the culture is sufficient to drive cardiac differentiation and generate CM with high purity10. In spite of this, adherent culture systems have limited scalability and are not practical to support the anticipated CM requirements of clinical trials. Alternatively, using an embryoid body (EB) differentiation method, a complex cardiac induction procedure involving stage-specific treatments with growth factors and small molecules to modulate Activin/Nodal, BMP, and Wnt pathways has been reported to be effective in cardiac differentiation in a suspension culture system9, 11. However, the process of generating EBs is inefficient, rendering this method impractical for large scale CM production. An additional limitation of these approaches for scale-up application is that both methods are based on the expansion of the hPSCs in adherent culture and the subsequent CM differentiation process in either adherent culture or as EBs. The labor intensiveness and limited scalability of current processes have been the primary bottle necks to the large scale production of CM for clinical applications of hPSC-derived CM.

Pre-clinical studies suggest that doses of up to one billion CM will be required to achieve therapeutic benefit after transplantation14, 15. In order to meet the current CM demand for pre-clinical studies and the anticipated demand for foreseeable clinical studies, development of a robust, scalable and cGMP-compliant differentiation process for the production of both hPSCs and hPSC-derived CM is essential. Suspension cell culture is an attractive platform for large scale manufacture of cell products for its scale-up capacity. Application of a suspension culture platform to support hPSC growth in matrix-free cell aggregates has been well established16–21. We previously also reported the development of a defined, scalable and cGMP-compliant suspension system to culture hPSCs in the form of cell aggregates21. With this suspension culture system, hPSC cultures can be serially passaged and consistently expanded. In the present study we adapted our suspension culture system to establish a robust, scalable and cGMP-compliant process for manufacturing CM. We were able to use hPSC aggregates generated in the suspension culture system directly to produce CM with high efficiency and yield in suspension with various scales of spinner flasks. We optimized various critical process parameters including: small molecule concentration, induction timing and agitation rates for differentiation cultures in spinner flasks with scales up to 1 L. In this study, we integrated undifferentiated hPSC expansion and small molecule-induced cardiac differentiation into a scalable suspension culture system using spinner flasks, providing a streamlined and cGMP-compliant process for scale-up CM differentiation and production.

Materials and methods

hPSC suspension cultures

We routinely maintained the hPSCs lines H7 (WA07, WiCell), ESI-017 (BioTime), and a hiPSC line (a gift from Dr. Joseph Wu, Stanford) in the form of cell aggregates in suspension culture as previously described21. Briefly, suspension-adapted hPSCs were seeded as single cells at a density of 2.5–3×105 cells/mL in 125, 500, or 1000 mL spinner flasks (Corning) containing culture medium (StemPro hESC SFM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Life Technologies) with 40 ng/mL bFGF (Life Technologies) and 10 μM Y27632 (EMD Millipore). Stirring rates were adjusted to between 50–70 rpm depending on the vessel size and hPSC line. Medium was changed every day by demi-depletion with fresh culture medium without Y27632. Cells were dissociated with Accutase (Millipore) into single cells and passaged every 3–4 days when the aggregate size reached approximately 300 μm. Cell suspension cultures were maintained in 5% CO2 with 95% relative humidity at 37°C.

Calculation of sizes of cell aggregates

Aliquots of aggregates from the suspension cultures were evenly spread in 24- or 6-well plates as necessary to allow adequate separation of aggregates. A minimum of 3 pictures were taken of different areas from the edge to the middle of a well under a microscope. The pictures were analyzed with ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics). At least 200 cell aggregates in the pictures were randomly circled and the sizes of individual cell aggregates and average sizes of selected aggregates were calculated using the software.

Differentiation of hPSC to CM in suspension

Undifferentiated hESC aggregates generated from suspension cultures were directly used for differentiation in suspension without cell dissociation. Low attachment 6-well plates and spinner flasks in sizes of 125, 500, and 1000 mL were used for differentiation. The differentiation cultures were maintained in 5% CO2 with 95% relative humidity at 37°C. RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies) with 1× B27® Supplement minus insulin (Life Technologies) was used as the basal medium from CHIR and IWP-4 induction through 2 days post IWP-4 induction. Two days after IWP-4 induction, RPMI 1640 with 1× B27® Supplement (Life Technologies) was used as basal medium. Thereafter, 60–80% of media was change every 2–3 days until cell harvest. Briefly, induction would be initiated on the day hPSC aggregates reached an average size between 160–280 μm. On day 0 of induction, the aggregates were induced with CHIR (Stemgent) at various concentrations. On day 1 the medium was changed to remove the CHIR. On day 2 or 3 IWP-4 (Stemgent) was added at various concentrations for 2 days. On day 4 or 5, the medium was changed to remove IWP-4. After 2 days of IWP-4 induction, basal medium alone were used for further differentiation as described previously.

Cryopreservation

At harvest, CM aggregates were dissociated with Liberase TH (Roche) at 37°C for 20–30 min. After washing with PBS, the CM aggregates were further dissociated into single cells with TrypLE (Life Technologies) at 37°C for 5–10 min. Dissociated single CM at 1–3×107 cells/mL were cryopreserved with CryoStor CS10 (Biolife Solutions, Inc.) supplemented with 10 μM Y27632 in liquid nitrogen. To carry cells in adherent culture, cryopreserved cells were thawed and plated in 6-well plates coated with Synthemax (Corning) at cell seeding density 1–3×106 cells per well with 3 mL culture medium RPMI supplemented with B27.

Flow Cytometry

Analysis of the cell surface markers Tra-1-60, SSEA-4, ROR2, PDGFR-α, and CD90: Cells were enzymatically dissociated to single cells, washed in PBS, and counted using a hemocytometer. 2–3×105 cells were resuspended in FACS buffer composed of 0.5% BSA in PBS and incubated with directly conjugated antibodies for 30 min on ice. After incubation, cells were washed 3 times in FACS buffer and analyzed with an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The antibodies used were: Anti-SSEA-4-PE conjugated (R&D Sysstems), Anti-Tra-1-60-FITC conjugated (BD Biosciences), APC Mouse Anti-Human CD90 (BD Biosciences), mROR2-PE conjugated (FAB20641P, R&D Systems), mPDGFr-alpha-APC conjugated (FAB1264A, R&D Systems).

Analysis of the intracellular marker Oct-4 and cTnT: Cells were enzymatically dissociated to single cells, washed in PBS, and counted using a hemocytometer. Cells were then fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Subsequently, cells were washed in PBS, permeabilized in PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA and 0.1% saponin (permeabilization buffer) for 10 min at room temperature. 2–3×105 cells were resuspended in permeabilization buffer and incubation with conjugated Oct-4 antibody or cTnT primary antibody for 30 min on ice. Cells stained with cTnT primary antibody were then washed 3 times in permeabilization buffer and incubated with secondary antibody (diluted in permeabilization buffer) for 30 min on ice. After incubation, cells were washed 3 times in FACS buffer and analyzed by Accuri C6. The antibodies used were Anti-Oct3/4-PE conjugated (BD Biosciences) and Anti-Cardiac Troponin T antibody [1C11] (Abcam), and secondary antibody for anti-cardiac Troponin T antibody was R-PE goat anti-mouse IgG (Southern Biotech).

RNA sequencing

Transcriptome sequencing libraries were constructed with TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit V2 (Illumia) with minor modifications. In brief, 500 ng of total RNA from each sample was used for polyadenylated RNA enrichment with oligo dT magnetic beads, and the poly(A) RNA was fragmented with divalent cations at 94°C for 8 min. First strand cDNA was synthesized using random oligonucleotides and SuperScript II (Life Technologies). Second strand cDNA synthesis was subsequently performed using DNA Polymerase I. Double stranded cDNA was further subjected to end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation in accordance with the manufacturer supplied protocols. Purified double strand cDNA templates with ligated adaptor molecules on both ends were selectively enriched by 10 cycles of PCR for 10 s at 98°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C using Illumina PCR Primer Cocktail and Phusion DNA polymerase (Illumina). PCR products were cleaned using 1.0 × AmpureXP beads (Beckman Coulter). Purified libraries were validated using Bioanalyzer 2100 system with DNA High Sensitivity Chip (Agilent) and quantified with Qubit (Life Technologies). All libraries were sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq 2500 with single 40 bp reads following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Immunocytochemistry

Single cell-dissociated CM were seeded on Synthemax II-coated glass bottom Petri dishes for 2–3 days. Cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized using 0.1% triton X-100 for 30 min followed by blocking in 5% normal goat serum for 60 min at room temperature. After permeabilization and blocking, the cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, mouse anti-α-Actinin (Sigma), mouse anti-cTNT (Abcam), rabbit anti-cTNT (Abcam), or rabbit anti-cTNI (Abcam), at 1:100. The samples were rinsed 3× with PBST for 30 min and incubated with secondary antibodies (Cy3 anti-rabbit or FITC anti-mouse, Millipore; 1:500) overnight at 4 C, rinsed, applied a drop of Prolong Gold Anti-fade reagent containing DAPI (Life Technology), and covered with a coverslip. The images were acquired with multiphoton laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510).

Electrophysiology

Whole cell action potentials were recorded with the use of standard patch-clamp technique, as previously described8, 22, 23. Cultured hESC-derived cardiomyocytes (H7 CMs) were dissociated using TrypLE for 10 min at 37 °C, centrifuged at 200×g, suspended in the RPMI media supplemented with B27 (RPMI+B27) and filtered through a 100 μM cell strainer (BD Biosciences), and plated as single cells (1 × 105 cells per well of a 24-well plate) on No. 1 8 mm glass cover slips (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA) coated with Matrigel (1:50 ratio) in RPMI+B27 media supplemented with 2 μM thiazovivin and allowed to attach for 48–72 hrs, changing the media every other day. Cells were then placed in a RC-26C recording chamber (Warner) and mounted onto the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The chamber was continuously perfused with the perfused with warm (35–37 °C) extracellular solution of following composition: (mM) 150 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.0 Na pyruvate, 15 HEPES, and 15 glucose; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Glass micropipettes (2–3 MΩ tip resistance) were fabricated from standard wall borosilicate glass capillary tubes (Sutter BF 100-50−10, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) using a programmable puller (P-97; Sutter Instruments) and filled with the following intracellular solution: 120 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA and 3 mg ATP; pH was adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. A single beating cardiomyocyte were selected and action potentials (APs) were recorded in whole cell current clamp mode using an EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Data were acquired using PatchMaster software (HEKA, Germany) and digitized at 1.0 kHz. The single cells were paced at constant pacing rate of 1 Hz using a 5–20 ms depolarizing current injections of 150–550 pA. The following are the criteria used for classifying observed APs into ventricular-, atrial- and nodal-like cardiomyocytes. For ventricular-like, the criteria were a negative maximum diastolic membrane potential (<−50 mV), a rapid AP upstroke, a long plateau phase, AP amplitude > 90 mV and AP duration at 90% repolarization/AP duration at 50% repolarization (APD)90/APD50 < 1.4. For atrial-like, the criteria were an absence of a prominent plateau phase, a negative diastolic membrane potential (<−50 mV) and APD90/APD50 > 1.7. For Nodal-like, the criteria were a more positive MDP, a slower AP upstroke, a prominent phase 4 depolarization and APD90/APD50 between 1.4 and 1.78.

GMP compliance

To meet GMP compliance, the processes for cardiomyocyte production from hPSC expansion and cardiac differentiation to cell cryopreservation are defined and standardized. Reagents, materials, and procedures are validated and verified by documentation.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. The statistical significance was determined using two-tailed Student’s t test. Statistical significance was indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Results

Optimization of cardiomyocyte differentiation in small scale of static suspension

Manipulating Wnt signaling with small molecules at different differentiation stages has been reported to efficiently induce hPSC to CM in adherent cultures10. Using a similar approach, we developed a cardiac differentiation process for hESCs in a suspension culture system by induction with the Wnt activator, CHIR99021 (CHIR), followed with the Wnt inhibitor, IWP-4. With our previously described hESC suspension culture system21, undifferentiated H7 cells were adapted to suspension culture in the form of cell aggregates. The suspension culture can be serially passaged and expanded as aggregates in suspension culture (Fig. 1a) while maintaining expression of pluripotency markers in over 90% of cells. The undifferentiated cell aggregates were directly used for cardiac differentiation in suspension culture. To optimize cardiac differentiation, we first titrated CHIR and IWP-4 in 6-well plate static suspension culture. As cell aggregate size may affect induction efficiency, we evaluated the relationship between aggregate size and CHIR concentration. Cell aggregates on days 1, 2, and 3 of suspension cultures representing different size ranges had an average diameter of 159±28 μm, 211±40 μm, and 270±49 μm, respectively (Fig. 1b–d). The cell aggregates from each day maintained >95% positive for pluripotency markers (Fig 1d). CHIR was then titrated at 6, 12, 18, and 24 μM in basal medium on day 0 of induction for 24 hrs. IWP4 at 5 μM was added on day 3 of induction for 48 hrs. It has been previously reported that activation of the Wnt pathway by CHIR can induce early mesodermal differentiation10. To evaluate CHIR induction efficiency, the expression of ROR2 and PDGFRα, which were previously identified as mesoderm and cardiac mesoderm markers9, 24, 25, were used to track cardiac mesoderm differentiation by flow cytometry. One set of representative results for analysis on day 2 of differentiation (Fig 2a) showed that without CHIR, cell aggregates seeded from different size ranges of day 1 (first row), 2 (second row), and 3 (third row) suspension cultures did not differentiate to ROR2 and PDGFRα positive cells. However, CHIR concentrations starting from 6 μM were able to induce aggregates seeded from the day 1 suspension culture to generate approximately 42–83% ROR2+PDGFRα+ cells. In contrast, the cell aggregates of the day 2 suspension culture induced by 6 μM CHIR only gave rise to 14% ROR2+PDGFRα+ cells, suggesting an insufficient induction of cardiac mesodermal cells. CHIR concentration of 12 μM could efficiently drive the differentiation to generate approximately 65–72% ROR2+PDGFRα+ cells. However, when cell aggregates in the size range of the day 3 suspension culture were used for CHIR titration, only 5–8% ROR2+PDGFRα+ cells were detected at induction with CHIR >12 μM. Notably, when 24 μM CHIR was used for induction, a significant amount of dead cells was observed, indicating increased cytotoxicity at higher CHIR concentration. Overall, the results showed that day 1 cell aggregates with a smaller size differentiated into ROR2+PDGFRα+ mesodermal cells more efficiently at CHIR induction, while the differentiation efficiency declined when larger cell aggregates were used for induction (Fig. 2b) The results of cardiac differentiation efficiency assessed for cardiac Troponin T (cTnT)-positive cells on day 18 (Fig. 2c) showed that use of day 1 cell aggregates for differentiation generated a broad variability. Aggregates seeded from the day 2 culture exhibited a better cardiac differentiation with generation of 66±10% and 50±15% cTnT+ cells when induced with 12 and 18 μM CHIR. For cell aggregates harvested from day 3 culture, cardiac differentiation efficiency increased when higher CHIR concentrations were used for induction. These results suggest that cardiac differentiation efficiency is dependent on both the CHIR concentration and aggregate size.

Figure 1.

Analysis of H7 cell aggregates generated from suspension culture. (a) H7 cell expansion in suspension culture was calculated for 10 passages. (b) H7 cells formed different aggregate sizes in day 1, 2, and 3 suspension cultures. Scale bar, 200 μm. (c) Cell aggregates from the day 1, 2, and 3 suspension cultures were evaluated for their sizes. Aggregate sizes were analyzed by taking pictures of cell aggregates from culture aliquots and measuring aggregate sizes from the pictures using ImagePro software. The plot shows the distribution of aggregate sizes. n=3 independent experiments. Error bars, s.e.m. (d) Average size of day 1, 2, and 3 cell aggregates were calculated. n=3 independent experiments. Cells from dissociated aggregates were analyzed by flow cytometry for pluripotency markers, Tra-1-60, SSEA-4, and Oct-4.

Figure 2.

Titration of CHIR and IWP-4 for different aggregate size ranges of H7 suspension cultures seeded in 6-well plates for cardiac differentiation. (a,b) H7 cell aggregates with different size ranges from day 1, 2, and 3 suspension cultures, as indicated, in 125mL spinner flask were plated in static suspension in low-attachment 6-well plates for cardiac differentiation. CHIR concentrations of 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 μM were added for 24 hr to induce differentiation. ROR2+ and PDGFRα+ cell populations were measured by flow cytometry 2 days post CHIR induction. One representative result is shown in (a). Results of three independent experiments are shown in (b), Error bars, s.e.m. (c) With 2 days of IWP-4 induction on differentiation day 3–5, population sizes of cTnT+ cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 18 of differentiation. n=3 independent experiments, Error bars, s.e.m. (d) IWP-4 at concentrations 0, 1, 5, and 15 μM were added on day 3–5 after induction of 12 and 18 μM CHIR on cell aggregates with size range of day 2 suspension culture. Percentage of cTnT+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry on day 18 of differentiation. n=3 independent experiments, Error bars, s.e.m.

Following the CHIR titration study, we titrated IWP-4 to further improve cardiac differentiation efficiency. Cell aggregates harvested from day 2 suspension culture with an average size of 200±20 μm were used for IWP-4 titration as aggregates in this size range could be efficiently induced by a broader concentration range of CHIR. Following the differentiation procedure described above, cell aggregates were first induced with 12 and 18 μM CHIR on day 0 followed by 1, 5, and 15 μM IWP-4 on day 3 of differentiation. The results showed that without IWP-4 addition the cells could still differentiate to CM with 12 and 18 μM CHIR induction alone, suggesting an endogenous mechanism inhibited Wnt signaling (Fig. 2d). However, addition of 1 and 5 μM IWP-4 enhanced cardiac differentiation.

Optimization of stirring rates for 125mL spinner flasks

With a baseline set of differentiation conditions optimized in 6-well plates, we optimized cardiac differentiation in 125mL spinner flasks. Previous reports showed that shear stress could affect CM differentiation26–29 so we first tested the effects of stirring rate on cardiac differentiation and CM yield. As previous results showed that the ROR2+PDGFRα+ cardiac mesoderm population emerged as early as day 2 of differentiation (Fig. 2a), we also evaluated the effect of IWP-4 induction timing (day 2 vs. day 3) on cardiac differentiation efficiency. Differentiation was performed with IWP-4 added on day 2 or 3 at stirring rates of 35, 45, and 55 rpm. At a stirring rate of 35 rpm, the cardiac mesodermal population on day 2–4 of differentiation, marked by ROR2 and PDGFRα, were relatively small as compared with those from cultures stirred at 45 or 55 rpm in both conditions with IWP-4 added on day 2 and 3 (Fig. 3a, 3b). When analysis of cTnT+ cells on day 8 and 18, IWP-4 induction on day 2 showed a trend of better cardiac differentiation compared to day 3 induction, and at 45 rpm the cardiac differentiation exhibited better efficiency and consistency with 86±9% cTnT+ cells on day 18 (Fig. 3c,3d). Additionally, we observed that the differentiating aggregates developed at 35 rpm tended to fuse and formed larger aggregates. In contrast, the size of differentiating aggregates was smaller at 55 rpm (Fig. 3e). These results highlights the sensitivity of cardiac differentiation culture to shear and that effective cardiac differentiation only occurs within a certain range of agitation, or shear.

Figure 3.

Optimization of stirring rate for cardiac differentiation in 125mL spinner flasks. Undifferentiated H7 cell aggregates of day 2 suspension cultures were induced for cardiac differentiation in 125 mL spinner flasks with stirring rates of 35, 45, and 55 rpm. IWP-4 addition on day 2 (D2-IWP) and day 3 (D3-IWP) were compared in this setup. (a,b) The population sizes of ROR2+ and PDGFRα+ cells were measured by flow cytometry on day 2, 3, and 4 of differentiation. The results for IWP addition on day 2 is shown in (a) and addition on day 3 is shown in (b). n=3 independent experiments, Error bars, s.e.m. (c,d) Percentage of cTnT+ cells was measured by flow cytometry on day 8 (c) and 18 (d) to compare cardiac differentiation efficiency. n=3 independent experiments, Error bars, s.e.m. (e) Sizes of EBs formed in different agitation rates were compared on day 18 of differentiation.

Titration of CHIR99021 and IWP-4 induction timing for stirred suspension cultures in spinner flasks

Considering that agitation and shear of a dynamic suspension culture might change the optimal condition of CM differentiation, we chose to re-optimized parameters in the 125mL spinner flask. Based on the previous results from static suspension cultures in 6-well plates and the stirring rate evaluation in 125mL spinner flasks, 3, 6, 12, and 18 μM CHIR were used to induce cell aggregates with an average size range of 200±20 μm in 125mL spinner flasks with an agitation rate of 45 rpm. IWP-4 induction time on day 2 and day 3 were also compared in the setup of CHIR titration. Analyses of the day 2 and day 3 differentiation culture showed that cell aggregates induced with 3 μM CHIR generated <4% ROR2+PDGFRα+ cardiac mesoderm cells, an indication of insufficient induction (Supplementary Fig. 1). When induced with 6 μM CHIR, the ROR2+PDGFRα+ cells increased to 20±11%. When induced with 12 and 18 μM CHIR, the ROR2+PDGFRα+ population surged significantly to 68±12% and 65±8%, respectively, on day 2 of differentiation (Fig. 4a). Notably, in the day 3 differentiation culture, the size of the double positive population was maintained over 70% when IWP-4 was added on day 2 (Fig. 4a). In contrast, without addition of IWP-4 on day 2, the size of the double positive population decreased on day 3 of differentiation (Fig. 4a). When analyzed for cTnT+ population on day 18, the cultures induced with 12 and 18 μM CHIR displayed better cardiac differentiation of 94±5% and 68±18% cTnT+ cells, respectively, when IWP-4 was added on day 2 of differentiation (Fig. 4b). In contrast, when IWP-4 was added on day 3, the cardiac differentiation was poor and was not comparable with previous results of optimization with the static suspension, which was performed with IWP-4 induction on day 3 (Fig. 2b,4b). This result suggest that the cardiac induction conditions for the static suspension culture may not provide the same cardiac differentiation efficiency for the dynamic suspension system, and thus adjustment of the differentiation parameters may be required to achieve an efficient cardiac differentiation for different suspension culture platforms.

Figure 4.

Titration of CHIR and IWP-4 induction timing for cardiac differentiation in spinner flasks. CHIR concentrations of 6, 12, and 18 μM, with IWP-4 addition on day 2 (D2-IWP) or day 3 (D3-IWP) were compared for their cardiac induction efficiency in stirred suspension cultures using 125mL spinner flasks. (a) The population sizes of ROR2+ and PDGFRα+ cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 2 and 3 of differentiation to compare induction efficiency. The result of day 3 differentiation with IWP-4 addition on day 2 is labeled as Day 3/D2-IWP. n=3–5 experiments, Error bars, s.e.m. (b) Percentage of cTnT+ cells on day 18 was measured to evaluate cardiac differentiation. CHIR concentrations and IWP-4 addition timing are indicated in the figures. n=3–4 independent experiments, Error bars, s.e.m. (c) Population sizes of cTnT+ cells were compared on day 8 (D8) and 18 (D18) for cardiac differentiation performed in parallel in 1L and 125mL spinner flasks and 6-well plates with optimal induction conditions of 1L spinner flask culture, which was induced with 18 μM CHIR. The culture vessel and day of analysis are indicated. n=3 independent experiments, Error bars, s.e.m. (d) Cardiac differentiation efficiencies of H7, ESI-017, and the iPSC lines in 125 mL spinner flask cultures induced by 6 and 12 μM CHIR were compared by measuring cTnT+ cell population. CHIR concentrations and cell lines are indicated. n=2–4 independent experiments, Error bars, s.e.m.

Using the same strategy of re-optimizing CHIR concentration, timing of IWP-4 induction, and agitation rate at each increasing scale, cardiac differentiation of H7 cells was successfully scaled up from 125mL to 500mL and then 1L spinner flasks. With these optimized parameters, we were able to perform cardiac differentiation in suspension to manufacture cardiac products containing 90±6% cTnT with cell yields 1.8±0.2×106 cells/mL in 125mL spinner flasks (n=12), 92±3% cTnT with 2.3±0.3×106 cells/mL in 500 mL spinner flasks (n=3), and 96±3% cTnT with 1.4±0.4×106 cells/mL in 1L spinner flasks (n=19).

As we optimized the differentiation parameters for the stirred suspension system, we noticed the optimal CHIR concentration and IWP-4 induction timing were varied among different scales of the spinner flasks. Other than the size difference, there are also differences in design of vessel geometry and impeller among various spinner flasks. To further assess if the differences in optimal differentiation parameters among different designs of spinner flasks was caused by shear characteristics unique to each type of the vessel, we applied the induction parameters (18 μM CHIR to induce differentiation followed by 5 μM IWP-4 addition on day 2 of differentiation) optimized for 1L spinner flasks to static 6-well plates, 125mL (with stirring rate of 45 rpm), 1L spinner flasks (with stirring of 32 rpm) and carried the cultures in parallel to compare their CM differentiation efficiency. Undifferentiated H7 cell aggregates from the same suspension cultures were seeded in each culture vessel using the same reagents prepared for cardiac differentiation. The only variable would be shear stress caused by agitation rate and vessel design. The results showed significant difference in the efficiency of cardiac differentiation among these 3 cultures, 93±7% cTnT for 1L spinner flask, 26±15% for 125mL spinner flask, and 51±22% for static 6-well plate on day 18 of differentiation, indicating that agitation and shear could affect cardiac differentiation and thus differentiation cultures in different vessel design will require individual optimization for CHIR concentration and IWP-4 induction timing to achieve optimal differentiation efficiency (Fig 4c).

Optimization of CM differentiation conditions for ESI-017 and a hiPSC line

It has been reported that different hPSC lines may require re-optimization of cardiac differentiation conditions9. Using the same strategy as before, we optimized differentiation conditions for an additional hESC line, ESI-017, and a hiPSC line and also tested if the cardiac differentiation conditions optimized for H7 could be applied to those cell lines. In short, the undifferentiated hPSC line was adapted to suspension culture in 125mL spinner flask. Subsequently, cell aggregates with a size range of 200±20 μm μm were used for cardiac differentiation in 125mL spinner flasks. With optimized differentiation conditions, which using 6 μM CHIR for induction, ESI-017 and the hiPSC line gave rise to 91±4% cTnT+ cells with a cell yield of 7.5±2.5×105 cells/mL and 94±4% cTnT with a cell yield of 2.0±0.5×106 cells/mL, respectively. We noticed that the optimal CHIR concentrations for cardiac differentiation of both ESI-017 and iPSC lines are different from H7. When induced with 12 μM CHIR, an optimal concentration for H7, ESI-017 and the hiPSC lines only generated 37±19% and 38±21% cTnT+ cells, respectively (Fig. 4d), indicating variability of induction conditions among different cell lines. While the cell lines we tested were able to generate high levels of CM, induction conditions, such as CHIR concentration, might require optimization for each cell line.

Kinetic analysis of the cardiac differentiation culture

The kinetics of cardiac differentiation induced in the suspension culture was examined in 1L spinner cultures. As analyzed by flow cytometry, the ROR2+PDGFRα+ cell population, representing cardiac mesoderm, did not come up on day 1 after CHIR induction, while it was drastically up-regulated on day 2 and increased modestly between days 3 and 5 after IWP-4 induction (Fig. 5a). Following 2 days of IWP-4 induction, the cTnT+ population emerged as early as day 6 and increased to approximately 90% by day 12 (Fig. 5b). The cell surface marker CD90, known to be expressed on hESCs, mesenchymal cells and fibroblasts, was used to detect those non-cardiac cells in the differentiated CM products. In contrast to the rapid increase in cTnT+ cells, the CD90+ population gradually decreased during differentiation (Fig. 5b). Gene expression analysis (Fig. 5c) showed that the pluripotency markers, POU5F1, NANOG, SOX2, and ZFP42 (Rex-1), were down-regulated immediately after induction with CHIR. In contrast, early mesodermal genes, including T, MIXL1, and GSC, were transiently up-regulated from day 1 to 3 after CHIR induction. ROR2 and ANPEP, recently identified to mark mesodermal cells giving rise to cardiovascular cells24, reached peak expression between days 2 and 3 and declined between days 4–6. Similarly, the cardiac mesoderm marker, MESP1, also displayed a transient expression surge on days 2–3. PDGFR-α, another gene marking early cardiac mesoderm and progenitor cells, was significantly up-regulated on day 2, reached the maximal expression on days 4–5, and then gradually declined. A core set of transcription factors, including GATA4, TBX20, TBX5, Isl1, Nkx2-5, and MEF2c, plays a critical role in coordinating regulation of cardiac progenitor differentiation. Among these genes, the onset of GATA4 was first detected as early as day 1, followed by TBX20 initiated on day 2 and Isl1 on day 3. TBX5, NKX2-5, and MEF2C then started to express on days 4–5. Expression of genes encoding cardiac contractile proteins, MYL7, MYH6, MYH7, TNNT2, TNNI1, and ACTN2, were detected at different time points, while drastic expression surges were observed on days 6–8 and sustained high expression hence. HCN4, regulating the generation of pacemaker action potentials, started to express on days 6–8. The expression surge of these genes appeared consistent with the observation of aggregation contractions beginning around day 8. Later than the expression of other cardiac genes, the gene IRX430, a transcription factor regulating differentiation of ventricular CM, was detected from day 8. Following IRX4 expression, MYL2, a ventricular marker, was up-regulated from day 10. The cardiac surface markers, EMILIN2, SIRPA, and VCAM1, were also up-regulated around day 6. From day 12 to 25, the expression of endoderm and ectoderm genes, such as SOX17, FOXA2, and NEUROD1, was barely detected, while the vascular genes, CDH5 and PDGFRβ, were in modest expression levels. Taken together, the analysis of gene expression showed that the cardiac differentiation induced by CHIR and IWP-4 in suspension followed a temporal cardiac development from the primitive streak-like cells/mesoderm, cardiac mesoderm, cardiac progenitor cells, to CM.

Figure 5.

Kinetics of cardiac differentiation in suspension culture. Samples from different time points were collected from the cardiac differentiation suspension culture. (a) Derivation of ROR2+ and PDGFRα+ cells was monitored by flow cytometry from day 0 to 5. (b) Percentages of CD90+ and cTnT+ cell populations were measured from day 6 to 25. n=3 independent experiments, Error bars, s.e.m. (c) Marker gene expression for pluripotency, mesoderm, cardiac mesoderm, cardiac progenitor, CM, and selected non-cardiac cells were analyzed by RNA-sequencing of samples from day 0 to 25. Gene expression levels (y-axis) were shown as RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads).

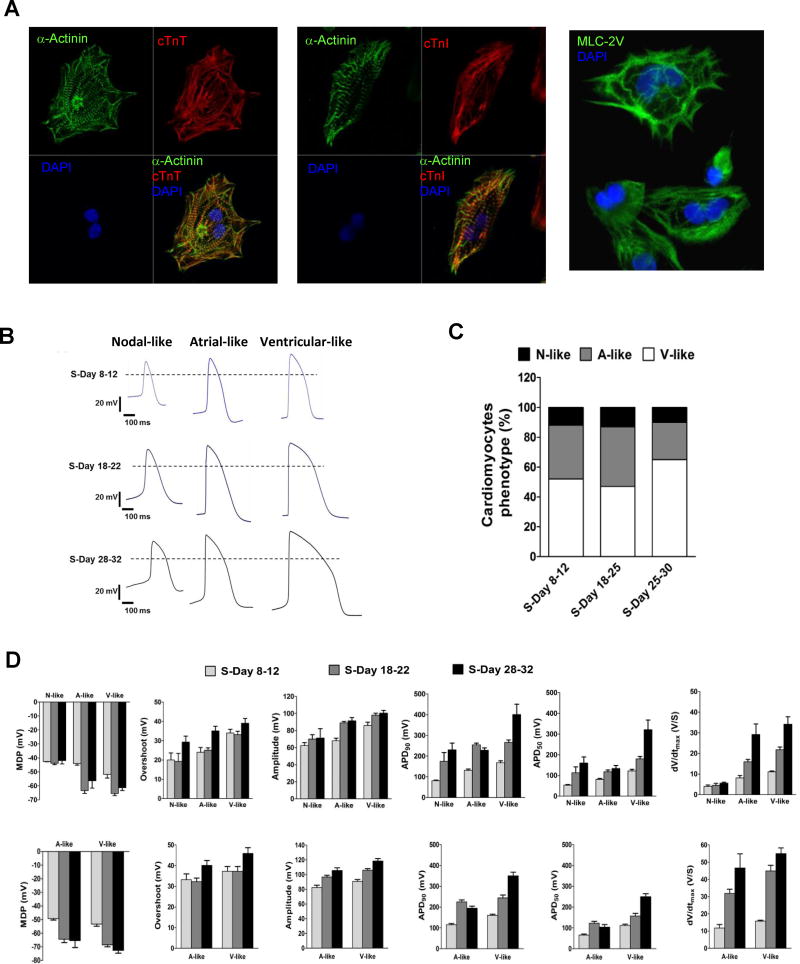

Characterization of PSC-derived CM from the suspension

CM generated in suspension can be plated and maintained as adherent cultures while contracting spontaneously for more than 2 months. Plated CM displayed typical striated structures of cardiac sarcomeres as stained by α-actinin, cTnT, cTnI, β-MHC, and MLC-2V (Fig. 6a). When analyzed for electrophysiological characteristics by patch clamp, the CM displayed action potentials (AP) representing nodal-, atrial-, and ventricular-like CM (Fig. 6b). The electrophysiological analyses also revealed a progressive maturation (or increase) in the key AP characteristics of the CM from days 8 to 28 (Fig. 6b–d) with days 8 cells exhibiting the most immature electrophysiological phenotype. Cells exhibiting the ventricular-like AP characteristics were the cell type predominant in the CM population, with approximately 47% on day 18 differentiation culture increased to 65% on day 28 (Fig. 6c). The average maximum diastolic potential (MDP) of ventricular-like (V-like) cells at days 8–12 were −55.8±2.6 mV compared to −61.3±2.0 (P<0.05; ±s.e.m.; Fig. 6d) at days 28–32 of differentiation in suspension culture. Similarly at days 28–32, the maximal upstroke velocity (Vmax) measured as V/s was 34.2±3.6 and was significantly (P<0.05) higher than days 8–12 CM. The results demonstrated a progressive time-dependent relative maturation of electrophysiological characteristics of the cells.

Figure 6.

Characterization of CM differentiated in suspension culture. (a) Cells differentiated in suspension culture were plated in adherent culture and stained with α-actinin, cTnT, cTnI, and MLC-2v antibodies, and DAPI. The immunofluorescent staining was acquired by confocal imaging. (b–d) Electrophysiological characterization of hESC-cardiomyocytes (hESC-CM) differentiated in suspension culture. (b) Representative action potential (AP) recordings using whole cell patch clamp of three cardiomyocyte subtypes produced at days 8–12, days 18–22, and days 28–32 of differentiation. Cells exhibit AP morphologies that can be categorized as atrial-, nodal-, or ventricular-like. (c) Subtype distribution of cardiomyocyte at days 8–12, n = 25, days 18–22, n = 30, and days 28–32, n = 20. (d) Patch clamp recordings of either spontaneously beating (top row) or paced (bottom row) hESC-CM at different time points differentiated in suspension culture, demonstrating MDP, maximum diastolic potential; peak voltage; APA, action potential amplitude; AP duration at different levels of repolarization (i.e., 90 or 50%); and dV/dtmax (maximal rate of depolarization).

Cryopreservation of CM

The H7-derived CM harvested from suspension cultures of 1L spinner flasks were tested for recovery and viability following cryopreservation. Cells were dissociated into single cells and cryopreserved in Cryostor CS10 freeze medium with a Rock inhibitor, Y-27632, in 2 different sizes, 1×107 cells/mL in 1 mL aliquots or 3×107 cells/mL in 2 mL aliquots using a control rate freezer. Vials from 7 production lots were then thawed, stained with trypan blue and total viable cells were counted to determine recovery and viability, respectively. From 20 cell lots, the average cell viability was 85.8±2.2% at thaw and recovery was 84.3±5.2%. Flow cytometric analysis of cTnT+ cells showed that cardiomyocyte purity was 91.6±7.6% after thaw, comparable to 92.0±7.9% before cryopreservation. The cryopreserved cells can be thawed and plated in adherent cell culture. Cell contraction was detected from day 1 after thaw (Supplementary Video). Cells dissociated from 6-day cultures maintained 95±1% viability (n=3 cell production lots) and retained 99±1% cTnT+ cells, comparable to a purity of 98±2% at thaw. The thawed cells retained action potential characteristics of CM as demonstrated by electrophysiological analysis which was shown previously (Fig. 6b,c).

Discussion

In this study we present a scalable suspension culture system to generate high purity and yields of CM from hPSCs in defined, matrix-free, serum-free and cGMP-compliant conditions. The cardiac differentiation process is a seamless extension of our hPSC suspension culture system, streamlining the manufacturing process from undifferentiated cell expansion to cardiac differentiation. The process can consistently produce CM with a purity of 96±3% and overall CM yields averaging 1.4±0.4×106 cells/mL with scale up to 1L spinner cultures. A fully suspension-based process avoids the scale limitations and extensive labor associated with adherent cultures. Suspension culture also eliminates the need for vessel coating for cell attachment. This reduces not only reagent costs, but also space and operators, further reducing production costs. These advantages render this manufacturing process more manageable, cost-effective, labor-effective, and practical for large-scale production of hPSC-derived CM.

EB formation method in suspension has been commonly used for hPSC differentiation. However, low efficiency of EB formation from hPSC adherent cultures has hindered the practical application of this method for large scale production of differentiated cells. In addition, EB formation in static suspension is not a reproducible process, particularly in the control of EB size, which has been shown to affect differentiation potentials27, 31. The suspension culture system we developed previously allows grows hPSCs in sphere-shaped aggregates with relatively homogeneous size21. Use of these cell aggregates as a starting cell substrate for cardiac induction avoids the EBs formation step. Aggregate size in our suspension culture system is readily controlled by seeding density, agitation rate and time in culture. With these advantages, the hPSC aggregate suspension culture is an ideal system for the production of CM.

One most recent study first reported the feasibility of using undifferentiated hPSC aggregates for cardiac differentiation in suspension by small molecules modulating Wnt pathway32. With a fixed differentiation condition without controlling cell aggregate size, the authors show cardiac differentiation efficiency ranging from 27.7% to 88.3% cTnT at scale up to 100mL using spinner flasks. Our study further provided a strategy for optimizing cardiac differentiation in suspension for different cell lines and suspension culture vessels. We identified and optimized a panel of critical parameters, including cell aggregate size, agitation rate, CHIR concentration, and IWP induction timing. With a tight control of those factors, we were able to achieve consistent and reproducible cardiac differentiation efficiency ranging from 80–99% cTnT for different cell lines and for spinner flasks at scales from 125mL up to 1L.

One notable finding of this study is that the optimal CHIR concentration for cardiac differentiation is dependent on the cell aggregate size. A higher concentration of CHIR is required to drive efficient cardiac differentiation from cell aggregates of larger sizes (Fig. 2). However, we also noticed that too high of a CHIR concentration is toxic to cells. Therefore, controlling cell aggregates in a proper size range at which they can be efficiently induced by non-toxic concentrations of CHIR is critical for achieving robust and consistent cardiac differentiation with maximal cell yield.

Shear stress generated by agitation in different designs of suspension culture vessels have been shown to affect cardiac differentiation27. Consistent with this report, our present study indicates that optimal cardiac differentiation with spinner cultures occurs within a tight range of stirring rates. Moreover, as alternative cell lines are used or the scale, design or impeller shape of the spinner flask is changed, differentiation conditions may have to be re-optimized. However, while the parameters for cardiac differentiation may need to be adjusted for each vessel type and cell line, the critical parameters CHIR concentration and IWP-4 induction timing as we determined for each scale of spinner flask, they can be readily estimated and optimized with a modest effort. The variation of optimal differentiation conditions could be due to the shear stress caused by different stirring and designs of spinner flasks. Therefore, it is important to understand the relationship between agitation and shear among different culture vessels and to test alternative suspension culture platforms that may provide more uniform and predictable shear during scale-up, such as bag-based rocking suspension33–35.

As we titrated CHIR for different hPSC lines in a similar size range of cell aggregates cultured in 125mL spinner flasks, we noticed that ESI-017 and the hiPSC line we used were more sensitive than H7 to CHIR toxicity. CHIR at 12 μM, the optimal concentration for H7, was toxic to ESI-017 and the hiPSC line, while concentration reduced to 6 μM could efficiently induce cardiac differentiation of both cell lines, but not H7. The variation of induction efficiency among cell lines has been reported previously using Activin A and BMP4 induction with EB formation method9, which showed that cardiac induction conditions required optimization for individual cell lines. Other than the sensitivity to small molecules and cytokines, variable levels of endogenous signaling may possibly cause the difference in the optimal CHIR concentrations for individual cell lines.

In summary, we present here a strategy to optimize cardiac differentiation in suspension culture and demonstrate a robust and scalable process for large-scale CM production. We have identified a number of critical process parameters, including cell aggregate size, agitation rate, CHIR concentration and timing of Wnt inhibition. Our study provides useful insights for future development of large scale cardiac differentiation in different types of suspension culture platforms. Application of this scalable suspension culture for CM production will address the current demand for the large number of CM required for pre-clinical and clinical studies.

Supplementary Material

Analyses of day 2 and day 3 differentiation cultures in 125mL spinner flasks showed that CHIR99021 at 3 μM induced <4% ROR2+PDGFRα+ cells (mesoderm/cardiac mesoderm cells).

Day 1 cell culture of cryopreserved H7 cardiomyocytes thawed and cultured on Synthemax.

Highlights.

We present a strategy to optimize cardiac differentiation in suspension for hiPSCs.

The matrix-free suspension platform integrates hPSC expansion and differentiation.

Cardiac production in suspension achieves >90% purity with 1L spinner flasks.

The production process in suspension is defined, scalable, and GMP compliant.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Joseph Wu at Stanford for providing a hiPSC line for testing cardiac differentiation, Light Microscopy Digital Imaging Core at City of Hope for assistance in confocal imaging, and Integrative Genomics Core at City of Hope for performing RNA-sequencing assay and data analysis. This work was supported by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) DR2-05394, and Production Assistance for Cellular Therapies (PACT) funded by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Arnold SJ, Robertson EJ. Making a commitment: cell lineage allocation and axis patterning in the early mouse embryo. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2009;10:91–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckingham M, Meilhac S, Zaffran S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nature reviews Genetics. 2005;6:826–835. doi: 10.1038/nrg1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tam PP, Loebel DA. Gene function in mouse embryogenesis: get set for gastrulation. Nature reviews Genetics. 2007;8:368–381. doi: 10.1038/nrg2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David R, et al. MesP1 drives vertebrate cardiovascular differentiation through Dkk-1-mediated blockade of Wnt-signalling. Nature cell biology. 2008;10:338–345. doi: 10.1038/ncb1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naito AT, et al. Developmental stage-specific biphasic roles of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiomyogenesis and hematopoiesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:19812–19817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605768103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueno S, et al. Biphasic role for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiac specification in zebrafish and embryonic stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:9685–9690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702859104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burridge PW, Keller G, Gold JD, Wu JC. Production of de novo cardiomyocytes: human pluripotent stem cell differentiation and direct reprogramming. Cell stem cell. 2012;10:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burridge PW, et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nature methods. 2014;11:855–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kattman SJ, et al. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell stem cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lian X, et al. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E1848–1857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200250109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, et al. Extracellular matrix promotes highly efficient cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells: the matrix sandwich method. Circulation research. 2012;111:1125–1136. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.273144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu WZ, Van Biber B, Laflamme MA. Methods for the derivation and use of cardiomyocytes from human pluripotent stem cells. Methods in molecular biology. 2011;767:419–431. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-201-4_31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong JJ, et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510:273–277. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Regenerating the heart. Nature biotechnology. 2005;23:845–856. doi: 10.1038/nbt1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amit M, et al. Suspension culture of undifferentiated human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem cell reviews. 2010;6:248–259. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9149-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krawetz R, et al. Large-scale expansion of pluripotent human embryonic stem cells in stirred-suspension bioreactors. Tissue engineering. 2010;16:573–582. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olmer R, et al. Long term expansion of undifferentiated human iPS and ES cells in suspension culture using a defined medium. Stem cell research. 2010;5:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh H, Mok P, Balakrishnan T, Rahmat SN, Zweigerdt R. Up-scaling single cell-inoculated suspension culture of human embryonic stem cells. Stem cell research. 2010;4:165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steiner D, et al. Derivation, propagation and controlled differentiation of human embryonic stem cells in suspension. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:361–364. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen VC, et al. Scalable GMP compliant suspension culture system for human ES cells. Stem cell research. 2012;8:388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leamy AW, Shukla P, McAlexander MA, Carr MJ, Ghatta S. Curcumin ((E,E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione) activates and desensitizes the nociceptor ion channel TRPA1. Neuroscience letters. 2011;503:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shukla P, et al. Maternal nutrient restriction during pregnancy impairs an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-like pathway in sheep fetal coronary arteries. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2014;307:H134–142. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00595.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ardehali R, et al. Prospective isolation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiovascular progenitors that integrate into human fetal heart tissue. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:3405–3410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220832110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drukker M, et al. Isolation of primitive endoderm, mesoderm, vascular endothelial and trophoblast progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature biotechnology. 2012;30:531–542. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geuss LR, Suggs LJ. Making cardiomyocytes: how mechanical stimulation can influence differentiation of pluripotent stem cells. Biotechnology progress. 2013;29:1089–1096. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niebruegge S, et al. Generation of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesoderm and cardiac cells using size-specified aggregates in an oxygen-controlled bioreactor. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2009;102:493–507. doi: 10.1002/bit.22065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shafa M, et al. Impact of stirred suspension bioreactor culture on the differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells into cardiomyocytes. BMC cell biology. 2011;12:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-12-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ting S, Chen A, Reuveny S, Oh S. An intermittent rocking platform for integrated expansion and differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to cardiomyocytes in suspended microcarrier cultures. Stem cell research. 2014;13:202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng SY, Wong CK, Tsang SY. Differential gene expressions in atrial and ventricular myocytes: insights into the road of applying embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for future therapies. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2010;299:C1234–1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00402.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bauwens CL, et al. Control of human embryonic stem cell colony and aggregate size heterogeneity influences differentiation trajectories. Stem cells. 2008;26:2300–2310. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kempf H, et al. Controlling expansion and cardiomyogenic differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells in scalable suspension culture. Stem cell reports. 2014;3:1132–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalmbach A, et al. Experimental Characterization of Flow Conditions in 2-and 20-L Bioreactors with Wave-Induced Motion. Biotechnology progress. 2011;27:402–409. doi: 10.1002/btpr.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oncul AA, Kalmbach A, Genzel Y, Reichl U, Thevenin D. Characterization of Flow Conditions in 2 L and 20 L Wave Bioreactors (R) Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Biotechnology progress. 2010;26:101–110. doi: 10.1002/btpr.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh V. Disposable bioreactor for cell culture using wave-induced agitation. Cytotechnology. 1999;30:149–158. doi: 10.1023/A:1008025016272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Analyses of day 2 and day 3 differentiation cultures in 125mL spinner flasks showed that CHIR99021 at 3 μM induced <4% ROR2+PDGFRα+ cells (mesoderm/cardiac mesoderm cells).

Day 1 cell culture of cryopreserved H7 cardiomyocytes thawed and cultured on Synthemax.