Abstract

An 80-year-old woman with Alzheimer's dementia presented with diarrhoea, vomiting and worsening confusion following an increase in donepezil dose from 5 to 10 mg. The ECG revealed prolongation of QTc interval. Soon after admission, she became unresponsive with polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation with a 200 J shock was successful in establishing cardiac output. Following the discontinuation of donepezil, the QTc interval normalised and no further arrhythmias were recorded. Treatment with anticholinesterase inhibitors may result in life-threatening VT. Vigilance is required for the identification of this condition in patients presenting with presyncope, syncope or seizures.

Background

Some years prior, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, including donepezil, were recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), for the treatment of moderate Alzheimer's dementia.1 Their use was extended a few years later for the treatment of mild Alzheimer's dementia and Lewy-body disease, or for those patients with Parkinson's related dementia who have coexistent distressing symptoms or challenging behaviour. Recent studies, however, have also shown donepezil may be of potential benefit in patients with more severe Alzheimer's dementia and it is likely that the NICE guidance, which was reviewed in April 2014, will recommend their use for this group of patients.

The NICE recommendations suggest that the above treatment be started by doctors who specialise in dementia, and that patients undergo regular reviews by a specialist team to assess cognition, behaviour and ability to cope with daily life. They also suggest that anti-cholinesterase inhibitors be continued as long as the treatment is judged to have a positive effect. The side effects are primarily related to cholinergic and vagal tone inhibition. These include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, as well as others, including anorexia, dizziness, insomnia, bradycardia and aggravation of sinoatrial disease. Pretreatment ECG screening is not currently recommended by NICE. Anticholinesterase drugs such as donepezil, however, require careful administration in patients with co-existing sinoatrial or atrioventricular (AV) nodal disease.

Indeed, a small number of case reports suggest that some patients with bradycardia and underlying coronary artery disease, or those with biochemical abnormalities, may be at risk of developing life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias following treatment with donepezil. We report a patient without evidence of overt coronary artery disease or biochemical abnormalities who developed polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) while on treatment with donepezil.

Case presentation

An 80-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital via the emergency department, with a 2-day history of anorexia and diarrhoea. Her medical history included the presence of cerebrovascular disease with mixed vascular and Alzheimer's dementia, atrial fibrillation (AF) with prior VVI permanent pacemaker implantation for slow ventricular response, and hypertension. She was widowed, and despite her cognitive impairment, lived alone with support from her daughter. On admission to our hospital, she was on treatment with bumetanide 2 mg once daily, perindopril 8 mg once daily, lansoprazole 30 mg once daily, atorvastatin 20 mg once at night, diltiazem M/R 60 mg once daily, fluoxetine 60 mg once daily and donepezil 10 mg once daily. The latter drug had been increased from 5 to 10 mg daily 2 weeks earlier by the attending consultant psychiatrist. No ECG was performed prior to increasing the dose of donepezil.

Investigations

On admission, the patient was agitated but alert, with a body temperature of 35.9°C; she appeared mildly dehydrated and had an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The supine blood pressure was 148/82 mm Hg, and pulse rate was 85 bpm in AF. She had a pansystolic murmur in the apex in keeping with moderate mitral regurgitation. There were no signs of heart failure. The abdominal examination was unremarkable, as was the neurological examination.

Initial investigations revealed haemoglobin of 12.5 g/L and creatinine of 102 μmol/L. Liver function tests and inflammatory markers were normal as were serum sodium (143 mmol/L), potassium (4.1 mmol/L) and adjusted calcium (2.4 mmol/L). Chest radiograph was within normal limits and urine dip was negative. The patient's admission ECG, however, revealed prolongation of the QTc interval of 490 ms (in females, normal is <470 ms), with underlying paced rhythm.

Treatment

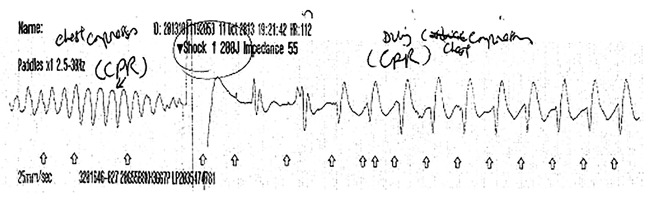

The patient was treated with intravenous fluids and donepezil was reduced to 5 mg daily. Twenty-four hours after admission, she became unresponsive and CPR was started. The ECG on the automated external defibrillators monitor demonstrated polymorphic VT (torsades de pointes) and a 200 J shock was delivered (figure 1). The patient made a rapid recovery and regained full consciousness. On direct questioning, she denied any preceding symptoms of chest pain, breathlessness or palpitations.

Figure 1.

Rhythm strip recorded during the resuscitation, showing polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and shock (arrow), followed by atrial fibrillation.

Post arrest serum magnesium and potassium were within the normal range at 0.75 and 4.2 mmol/L, respectively, with normal corrected calcium of 2.4 mmol/L. Post arrest QTc was prolonged at 550 ms. Echocardiography confirmed normal left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction 55%), long-standing bi-atrial dilation and moderate mitral regurgitation.

The patient was transferred to the coronary care unit (CCU) for constant ECG monitoring, and intravenous magnesium was given. Donepezil was discontinued and fluoxetine, which may also have contributed to the arrhythmic event, was reduced to 20 mg once daily, although the patient had been on her pre-admission dose for 10 years.

Subsequent coronary angiography confirmed mild coronary atheroma with no obstructive coronary lesions. The patient's case was discussed in a multidisciplinary electrophysiology meeting and a diagnosis of polymorphic VT due to QTc prolongation, following an increase in the dose of donepezil, was made. The patient did not meet the NICE criteria for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation given there was a clear and reversible precipitant.

Outcome and follow-up

Subsequent ECGs prior to discharge showed a gradual normalisation in the patient's QTc interval (431 ms).

Discussion

Centrally acting acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, have been reported to be effective in the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease by suppressing the progression of the disease and maintaining the ability to perception, cognition and global functioning.1 2 Common side effects include appetite loss, nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, dizziness, insomnia and aggravation of sick sinus nodal disease, mediated primarily through its cholinergic effects. The mechanisms by which the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors act on the myocardium are poorly understood. However, it is well established that neurons in the heart are rich in the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. Activation of cardiac acetylcholine receptors opens voltage-gated calcium channels, whereas inhibition of acetylcholinesterase may lead to increased intracellular calcium concentrations. This may in turn prolong phase 2 of the cardiac action potential thereby increasing the risk of ventricular arrhythmias.3

A small number of case reports have suggested a possible association between donepezil and heart block (first, second and complete) as well as ventricular arrhythmias, in particular polymorphic VT (torsades de pointes).3–5 In these case reports, one of the patients who developed torsades de pointes presented with acute colitis, diarrhoea hypokalaemia and prolongation of the QTc interval. That patient had had a previous anterior myocardial infarction, aneurysmal apex on echocardiography and three vessel coronary artery diseases on left heart catheterisation.4 Further two patients were diagnosed with symptomatic bradycardia (one with advanced second-degree block and one with slow AF) followed by polymorphic VT.4 Another patient developed torsades de pointes without QTc prolongation.4 Our patient had no underlying biochemical abnormalities or bradycardia (since she had a permanent pacemaker in situ) to predispose to the development of torsades de pointes. Fluoxetine and donepezil may both lead to prolongation of the QTc interval and predispose to the development of torsades de pointes. The timing, however, of the torsades de pointes occurring 2 weeks after increasing the dose of the latter drug appears to suggest a potential role of donepezil in causing the above arrhythmia.

Our case clearly demonstrates that treatment of dementia with anticholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil may, in a small number of patients, cause life-threatening VT. Extreme vigilance is therefore required for the early identification of this condition, more so if patients present with presyncope, syncope or seizures, and in those patients with pre-existing rhythm disturbances, for instance, slow AF, sinoatrial or AV nodal disease, or on cardioinhibitory drugs such as β-blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists. These patients may benefit from having their pulse measured, as well as a pretreatment baseline ECG to assess the PR, QRS and QTc duration, and a further clinical assessment with a resting ECG when on established therapy or prior to increasing the dose of the anticholinesterase inhibitor. In those patients presenting with presyncope, syncope, seizures, prolonged QTc or heart block, one should consider the discontinuation of anticholinesterase inhibitors, and cardiac evaluation should be undertaken urgently.

Learning points.

Anticholinesterase drugs such as donepezil, when used for the treatment of dementia, require careful administration in patients with co-existing sinoatrial or atrioventricular nodal disease.

Treatment with anticholinesterase inhibitors may result in life-threatening ventricular tachycardia in patients without overt coronary artery disease or biochemical abnormalities.

Vigilance is required for the identification of this condition in patients presenting with presyncope, syncope or seizures.

Footnotes

Contributors: JK contributed to conception and design, acquisition of the data or analysis and interpretation of the data. JK, RI, MA-O and CM contributed to drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.NICE TA127 Technology Appraisal. Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. NICE, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winbland B, Kilander L, Eriksson S et al. , Severe Alzheimer's Disease Study Group . Donepezil in patients with severe Alzheimer's disease: double-blind, parallel group, placebo controlled study. Lancet 2006;367:1057–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68350-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka A, Koga S, Hiramatsu Y. Donepezil-induced adverse side effects of cardiac rhythm: 2 cases report of atrioventricular block and torsade de pointes. Inter J Med 2009;48:1219–23. 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takaya T, Okamoto M, Yodoi K et al. Torsades de pointes with QT prolongation related to donepezil use. J Cardiol 2009;54:507–11. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadano Y, Ogawa H, Nakashima, et al.,. Donepezil-induced torsades de pointes without QT prolongation. J Cardiol Cases 2013;8:e69–71. 10.1016/j.jccase.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]