Abstract

Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome is a rare congenital abnormality characterised by varying degrees of aplasia or hypoplasia of the uterus and vagina. Very rarely, leiomyomas or adenomyosis can develop in the Müllerian remnant tissue or rudimentary uterus. We present a case of a 43-year-old woman with MRKH syndrome, who presented with primary amenorrhoea and lower abdominal pain. On examination, a large pelvic mass was palpated and a provisional diagnosis of ovarian tumour was made. MRI showed multiple large leiomyomas arising from the Müllerian remnant tissue, and chronic torsion of the right ovary.

Background

Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome is a rare congenital abnormality. Concurrent association of pelvic mass in a patient with MRKH is even rarer and poses a diagnostic challenge regarding its origin. This case illustrates the importance of radiological imaging, especially MRI, in such circumstances, to confirm the origin of the mass, define its relationship with adjacent structures and to propose possible differential diagnosis.

Case presentation

A 43-year-old woman with a history of primary amenorrhoea presented after experiencing 20 days of vague pain in the right iliac fossa. She had been evaluated for primary amenorrhoea in the past, and diagnosed to have a hypoplastic uterus.

On clinical examination, the patient had normally developed secondary sexual characters and breast development (Tanner's stage 5). Palpation of the abdomen showed a lobulated, mobile, firm mass arising from the pelvis. Speculum examination showed a blind vagina with absent cervix, and a solid mass was palpated at the fornices. The patient was referred for an ultrasound examination.

Investigations

Transabdominal ultrasound showed two large heterogeneously hypoechoic lobulated masses in the pelvis. The uterus and right ovary were not visualised. The left ovary was normal in size. Based on ultrasound, the possibility of a mass arising from the right ovary was proposed, and contrast-enhanced MRI of the pelvis was suggested for further characterisation of the mass, and to confirm the absence of the uterus.

On MRI, two large circumscribed masses were seen in the pelvis and hypogastrium. On T2-weighted images (figure 1A), the masses appeared heterogeneously hypointense compared to muscles. No obvious uterus was visualised. On postcontrast imaging, the masses showed moderate enhancement with central non-enhancing necrotic areas (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Sagittal T2-weighted and (B) sagittal postcontrast T1-weighted MRI showing two heterogeneously enhancing circumscribed masses (white arrows) in the pelvis and hypogastrium, which appear hypointense to muscle. The mass in the pelvis is indenting on the dome of the urinary bladder with preserved fat planes. No obvious uterine tissue is seen between the rectum and bladder (dashed white arrow).

Of note was an enlarged displaced right ovary, which appeared hyperintense on T2-weighted images and were located abnormally directly beneath the right rectus abdominis muscle (figure 2A). The right infundibulopelvic ligament, ovarian vascular pedicle and fallopian tube were twisted, suggesting ovarian torsion (figure 2B). The left ovary was normal in its location, size and signal intensity.

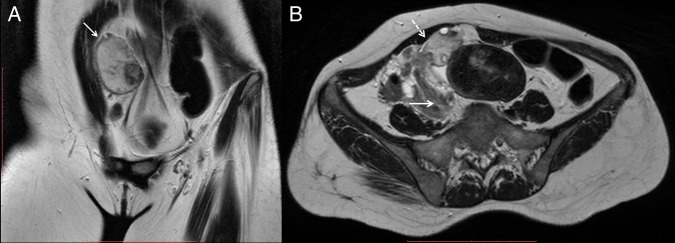

Figure 2.

(A) Coronal and (B) axial T2-weighted images showing an enlarged hyperintense right ovary (white arrow), with central afollicular stroma and multiple peripherally arranged cysts. The ovary is also abnormally located beneath the anterior abdominal wall. Right infundibulopelvic ligament, ovarian vascular pedicle and fallopian tube were twisted (dashed white arrow), suggesting ovarian torsion.

Differential diagnosis

On imaging, as both ovaries were visualised to be separate from the masses, it was concluded that the masses were of non-ovarian origin. The masses also had maintained fat planes with the urinary bladder and adjacent bowel loops, hence extravesical leiomyoma arising from the bladder and gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) arising from small bowel were considered less likely.

Based on the morphology and signal characteristics of the masses, a provisional diagnosis of MRKH syndrome with multiple leiomyomas, with areas of necrosis arising from the Müllerian remnants and torsion of the right ovary, was made.

Treatment

The patient underwent laparotomy. Intraoperatively, two large masses were seen arising from the Müllerian remnant uterine tissue. The right ovary was enlarged and congested due to torsion, and could not be salvaged. The left ovary was normal and was not removed as the patient was premenopausal.

The masses and the Müllerian remnants were removed, to avoid the risk of recurrence along with the torted right ovary. Histopathology confirmed the leiomyomas.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient's recovery was uneventful.

Discussion

MRKH syndrome is a rare congenital disorder that shows varying degrees of aplasia or hypoplasia of the uterus and vagina due to arrest in the development of the Müllerian ducts. The incidence of this condition is reported to be 1 in 4000–5000 female births.1

There can be various morphological manifestations of this syndrome, such as hypoplasia or absence of vagina, and either complete absence of uterus or bilateral rudimentary uterine anlage with a central fibrous band connecting them.2

Since the ovaries are normal, oestrogen-dependent pathologies such as leiomyomas, adenomyosis and neoplasms can develop in a rudimentary uterus. Similarly, since the proximal ends of Müllerian ducts have smooth muscles, development of leiomyomas in Müllerian remnants is possible, however, the incidence is rare. A possible reason proposed for this is reduced concentration or sensitivity of oestrogen receptors in these Müllerian remnants.3

In cases of MRKH syndrome presenting with a pelvic mass, differential diagnosis on MRI would include masses arising from the ovaries, such as ovarian fibroma, extra-ovarian masses such as GIST of the intestine and extravesical leiomyoma of the urinary bladder, and leiomyomas arising in the rudimentary uterine tissues or Müllerian remnants.

Ultrasonography is often the initial screening modality; it shows leiomyomas as circumscribed heterogeneous hypoechoic masses in the region of the pelvis. However, ultrasound has limitations, such as a poor sonological window, and operator skill might restrict accurate diagnosis regarding the origin of the masses.

MRI has an accuracy of 100% in diagnosing Müllerian anomalies.1 It has excellent soft tissue resolution and can characterise pelvic masses and thus guide further management. Leiomyomas appear hypointense to myometrium on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images, and can show moderate heterogeneous enhancement on postcontrast imaging.

Management of pelvic masses in a case of MRKH depends on the underlying pathology. Removal of the leiomyomas along with Müllerian remnants is advisable to avoid risk of recurrence.2

Learning points.

Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome is a rare congenital disorder that shows varying degrees of aplasia or hypoplasia of the uterus and vagina.

Since the ovaries are normal, oestrogen-dependent pathologies such as leiomyomas, adenomyosis and neoplasms can develop in a rudimentary uterus or in Müllerian remnants.

In cases of MRKH syndrome presenting with a pelvic mass, differentials that should be considered include masses arising from the Müllerian remnants, and masses arising from the ovaries, such as ovarian fibroma, gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the intestine and extravesical leiomyoma of the urinary bladder.

MRI has an accuracy of 100% in diagnosing Müllerian anomalies, and can characterise pelvic masses thus guiding further management.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rawat KS, Buxi T, Yadav A et al. . Large leiomyoma in a woman with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. J Radiol Case Rep 2013;7:39–46. 10.3941/jrcr.v7i3.1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soma S, Baidyanath C, Manju C et al. . Large fibroid arising from Mullerian remnant mimicking as ovarian neoplasm in a woman with MRKH syndrome. Int J Infertility Fetal Med 2012;3:30–2. 10.5005/jp-journals-10016-1037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhuyar SA. Rare case of leiomyoma in Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2014;3:488–90. 10.5455/2320-1770.ijrcog20140647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]