Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact of Mexico City and federal smoke-free legislation on secondhand tobacco smoke (SHS) exposure and support for smoke-free laws.

Material and Methods

Pre- and post-law data were analyzed from a cohort of adult smokers who participated in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Survey in four Mexican cities. For each indicator, we estimated prevalence, changes in prevalence, and between-city differences in rates of change.

Results

Self-reported exposure to smoke-free media campaigns generally increased more dramatically in Mexico City. Support for prohibiting smoking in regulated venues increased overall, but at a greater rate in Mexico City than in other cities. In bars and restaurants/cafés, self-reported SHS exposure had significantly greater decreases in Mexico City than in other cities; however, workplace exposure decreased in Tijuana and Guadalajara, but not in Mexico City or Ciudad Juárez.

Conclusions

Although federal smoke-free legislation was associated with important changes smoke-free policy impact, the comprehensive smoke-free law in Mexico City was generally accompanied by a greater rate of change.

Keywords: tobacco, public policy, tobacco smoke pollution, mass media

Smoke-free policies are fundamental to the World Health Organization - Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO-FCTC)1 because they decrease exposure to toxic second-hand tobacco smoke (SHS), reduce tobacco consumption and promote quitting,2,3 and shift social norms against smoking.4–6 When high- income countries ban all smoking within enclosed public places and workplaces, public support for smoke-free policies generally increases,7–11 even among smokers.7,9,10,12,13 However, weaker laws that allow smoking in designated areas have resulted in lesser or no change in smoke-free policy support.14

Across Latin American countries, support is generally high for banning smoking in all workplaces.15–17 Most Mexicans recognize the harms of SHS and support smoke-free policies.17–20 In early 2008, about 80% of Mexicans supported prohibiting smoking in enclosed public places and workplaces,19 and longitudinal research among Mexico City adults indicated similarly high levels of support, with significant increases in support after smoke-free policy implementation.21

Comprehensive smoke-free laws have been most successful when they are accompanied by mass media campaigns that reinforce the law’s rationale and encourage a new social norm of not smoking in public places.12,22,* Under such circumstances, substantial and consistent declines in SHS exposure are found across indicators, including those from observational studies,7,23 surveys of self-reported SHS exposure,7,12,24 biomarkers of SHS exposure,7,24,25 and air quality assessments.7,8 Nevertheless, and despite enjoying high levels of popular support, the implementation of smoke-free laws in low- and middle-income countries may encounter difficulties that stem from such factors as greater social acceptability of tobacco use, shorter histories of programs and policies to combat tobacco-related diseases, and a greater tolerance of law breaking.18,26,27 Longitudinal survey research among Mexico City inhabitants has suggested substantial decreases in SHS exposure after implementation of the city’s smoke-free policy.21 How- ever, compliance was not incomplete and no studies have assessed whether the Mexico City law was any more effective in reducing SHS exposure or shifting sup- port for smoke-free policies than the more ambiguous and weaker federal law that was implemented during the same period.

Mexican smoke-free legislation

Before 2008, smoke-free policies in Mexico were limited mainly to government buildings and hospitals,16 and compliance was generally low.28 In February 2008, however, the Mexico City legislature passed a local law that prohibited smoking inside all enclosed public places and workplaces, including restaurants, bars, and public transport.29–31 This law became effective on April 3, 2008. During the month before and after the law came into effect, the Mexico City Ministry of Health’s (MoH) community health promoters educated businesses about the law. During this time, the Mexico City MoH along with civil society organizations aired radio spots and disseminated print materials describing the rationale for the law.29 From September through December 2008, a campaign emphasizing the benefits of smoke-free policies and reinforcing the new smoke-free social norms was aired on television, radio, print media and billboards.22,*

In May 2008, the Mexican President signed federal legislation that prohibited most types of tobacco advertising, stipulated pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages, and established smoke-free areas within public places and workplaces. This federal law became effective in August 2008. At that time, the federal MoH ran a national radio and TV campaign that called attention to dangers of SHS and the benefits of smoke-free environments. Simultaneously, the government disseminated information about the new federal law, stating that smoking was banned in all enclosed workplaces, including restaurants and bars, until regulations were published to define the conditions under which smoking could take place. However, these regulations were not published until June 2009, which created some uncertainty among business owners and the public about the policy.

National and local Mexico City media coverage of these smoke-free laws was similar to that found in high- income countries. Analyses of print media indicate that coverage was mostly neutral or in favor of smoke-free policies, generally giving voice to arguments about the dangers of SHS and governments’ obligation to protect citizens from these dangers. However, arguments about discrimination against smokers, the rights of smokers, and the “slippery slope” of regulating behavior were also prevalent,5,31,32 and the volume of coverage against the smoke-free laws reached its apex in February 2008, when both federal and local legislation were at the point of passing their respective legislative chambers.32

This study aimed to determine the impact of the comprehensive smoke-free law in Mexico City compared to the federal smoke-free law, during the period when smoking was prohibited in all workplaces, before regulations appeared to defi designated smoking places. We used data collected from a panel of adult smokers at the end of 2007 (pre-law) and the end of 2008 (post-law), examining the prevalence and changes in exposure to SHS media campaigns, support for smoke-free laws, and self-reported SHS exposure in regulated venues.

Material and Methods

Study sample

Data were drawn from waves 2 and 3 of the Mexico administrations of the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project (ITC Project), an international effort to understand tobacco policy impacts among cohorts of adult smokers in different countries.16,33 The stratified, multistage sampling scheme has been described elsewhere in greater detail,17 but generally involved sampling block groups within four major cities (i.e., Mexico City, Guadalajara, Tijuana, and Ciudad Juárez). Face-to-face interviews were conducted with a random sample of approximately 270 adult smokers in each city. At wave 1, 64% of households approached were enumerated and 89% of eligible, selected participants were interviewed. Seventy percent (756/1 079) of wave 1 participants were successfully re-interviewed at wave 2, when data were collected between November and December 2007. Wave 2 data collection included replenishment with 289 randomly selected adult smokers who lived in the same or contiguous block groups within selected census tracts. Wave 3 data collection took place between November and December 2008, and 73% (762/1045) of the wave 2 sample was successfully re-interviewed. Those lost to follow up were replenished with randomly selected smokers who lived within the same census tracts (n=300). To increase the precision of estimates involving Mexico City, the sample size was increased there using identical sampling procedures to select new block groups and randomly select 135 eligible smokers who lived there. Sampling weights were developed to reflect the probability of selection of respondents and rescaled to equal the sample size within each city, in order to produce more efficient estimates34 and to avoid having Mexico City observations overwhelm observations from other cities. The protocol was approved by the ethics review board at the Mexican National Institute of Public Health, and all subjects provided written informed consent before participating.

Measures

Standard questions asked participants how much they agreed with prohibiting smoking in each type of venue that the smoke-free law regulated (i.e., workplaces in general; restaurants and cafés; bars, cantinas, and discotheques; hotels). Five-point Likert-scale response options, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, were dichotomized as strongly agree/agree (1) versus all else (0). Self-report questions from other studies35 were used to ask about SHS exposure in regulated venues. Participants who reported working in enclosed areas were asked how often someone had smoked inside their workplace during the previous 30 days (none; once; a few times; a lot; always), and responses were dichotomized as none (0) versus at least once (1). Participants who reported having gone to a public venue regulated by the smoke-free law in the previous 30 days (i.e., restaurants or cafés; informal eateries or fondas; bars or discos) were asked if anyone had smoked inside that venue during their last visit. Finally, participants were asked the last time they saw a smoke-free media campaign through each of the following channels: television; radio; news- papers or magazines; and billboards and posters. This question changed across waves, in order to increase sensitivity of exposure assessment for campaigns that emphasized smoke-free policy at wave 3 (i.e., campaigns that promote not smoking in enclosed areas) instead of the wave 2 focus on SHS dangers (i.e., campaigns about the dangers of tobacco smoke, wave 2). Response options were the same at both waves (i.e., last seven days; between a week and a month ago; between a month and six months ago; more than six months ago; never), and were dichotomized to reflect exposure within the previous six months (1) or not (0). Finally, standard questions were used to assess socio-demographics and smoking status (i.e., to account for people who quit over the study period).

Analyses

Data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.2. All analyses adjust for the complex sampling design using SAS survey procedures. Analyses assessing longitudinal change also adjusted for the non-independence of repeated observations by using the cluster statement for each individual. ANOVA was used to assess differences in the mean of continuous variables, both across cities and over time within cities. Similarly, chi-square tests were used to assess within and across city differences in categorical variables. For each survey period, we estimated the city-level prevalence of key indicators of interest (i.e., SHS campaign exposure through each media channel; support for smoke-free policies in each venue; self-reported SHS exposure in each venue). To assess statistical significance of city-level changes over time, data were pooled across waves and multiple logistic regression models were estimated for each city. Each indicator of interest was regressed on a binary variable indicating pre- vs. post-law assessment (i.e., wave 2 vs. wave 3) and control variables. To assess whether changes over time were different in Mexico City com- pared to other cities, data were pooled from all four cities and logistic models were estimated for each indicator of interest, regressing the indicator on the binary variable indicating pre- vs. post-law assessment, dummy variables for each city (with Mexico City as the referent group), an interaction between survey wave and city, and control variables. Finally, differences in prevalence at the post-law assessment involved estimating cross- sectional logistic regression models for each indicator as a function of control variables and city, and the statistical significance was examined for the adjusted odds ratios that compared each city with Mexico City.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table I shows the characteristics of the samples in each city at pre- and post-law. The percentage of the sample that was successfully followed ranged from highs of 88% (241/275) in Guadalajara and 78% (204/261) in Mexico City to lows of 62% (147/238) in Ciudad Juárez and 55% in Tijuana (149/271). No statistically significant socio- demographic, smoking- or policy-related differences were found between attrition and follow up samples, except for the higher income of the follow up sample in Juárez and the lower education of the follow up sample in Guadalajara. Within all cities, the percentage of female participants and monthly household income was stable over time. The Mexico City samples were similar in terms of age, education, current smoking status and working indoors, but in the follow up sample a lower percentage of people reported having gone to restaurants or fondas in the previous month, and more people reported going to bars. In Guadalajara, education and frequency of going to regulated venues remained consistent over time, but the post-law sample was slightly older, more likely to work indoors, and to have quit smoking. Both Tijuana samples had a similar prevalence of working indoors, having gone to bars in the previous month, and current smoking status; however, the post-law sample was slightly younger, had lower educational achievement and had higher prevalence of going to restaurants and fondas in the previous month. Finally, the Ciudad Juárez samples were comparable, except that the post- law sample had a higher prevalence of visiting fondas and bars in the previous month and was more likely to have quit smoking. Statistically significant differences across each city sample are indicated in Table I.

Table I.

Sample Characteristics in each study city, 2007 and 2008*

| Mexico City | Guadalajara | Tijuana | Ciudad Juárez | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Characteristics | Pre-law (n = 261) | Post-law (n = 399) | Pre-law (n = 275) | Post-law (n = 298) | Pre-law (n = 271) | Post-law (n = 253) | Pre-law (n = 238) | Post-law (n = 250) | |

| Mean / % | Mean / % | Mean / % | Mean / % | Mean / % | Mean / % | Mean / % | Mean / % | ||

| Age [range] | 39.4 [18 – 97] | 40.5 [18 – 98] | 41.7 g [18 – 86] | 43.2 [18 – 88] | 41.1h [18 – 82] | 37.9 [18 – 84] | 41.3 [18 – 79] | 41.6 [19 – 80] | |

|

| |||||||||

| Femalea | 43.4% | 42.9% | 45.4% | 48.7% | 33.2% | 33.8% | 41.7% | 47.0% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Educationa | Elementary or Primary School | 18.5% | 25.3% | 40.3% | 34.9% | 37.2%h | 27.3% | 43.7% | 43.1% |

|

| |||||||||

| Secondary School | 35.4% | 36.1% | 30.4% | 31.1% | 32.4% | 28.4% | 23.9% | 27.4% | |

|

| |||||||||

| High School or Technical School | 33.0% | 27.9% | 21.3% | 26.0% | 20.5% | 29.0% | 22.8% | 22.9% | |

|

| |||||||||

| University or more | 13.1% | 10.8% | 8.1% | 8.0% | 9.9% | 15.3% | 9.6% | 6.6% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Monthly Household Income (pesos)c |

0 to $1 500 | 4.1%g | 12.0% | 0.7% h | 1.3% | 9.2% | 4.6% | 10.2% | 5.6% |

|

| |||||||||

| $1 501 to $3 000 | 22.2% | 20.6% | 5.1% | 7.7% | 14.3% | 22.9% | 27.6% | 31.1% | |

|

| |||||||||

| $3 001 to $5 000 | 35.6% | 28.4% | 31.1% | 26.1% | 33.4% | 33.4% | 28.1% | 36.7% | |

|

| |||||||||

| $5 001 to $8 000 | 18.7% | 17.6% | 46.8% | 36.4% | 24.5% | 23.1% | 19.4% | 15.1% | |

|

| |||||||||

| $8 001 or more | 19.5% | 21.6% | 16.3% | 28.6% | 18.5% | 16.0% | 14.8% | 11.5% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Exposure to venues regulated by smoke-free laws | Works indoors | 31.5% | 32.3% | 36.8%h | 47.9% | 39.0% | 40.9% | 42.1% | 47.8% |

|

| |||||||||

| Went to a restaurant or café in last monthb | 36.1%g | 23.2% | 21.0% | 17.7% | 34.8%h | 20.0% | 13.2% | 14.5% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Went to a fonda in last monthc | 32.4% g | 23.1% | 17.4% | 24.2% | 34.1%i | 13.2% | 3.6%g | 9.8% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Went to bar or cantina in last montha | 13.1%h | 22.2% | 13.0% | 12.1% | 15.3% | 19.2% | 3.7%h | 11.3% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Current smoker (vs ex-smoker)c | 86.3% | 89.5% | 94.0%g | 89.0% | 85.8% | 88.1% | 94.4%h | 86.8% | |

pre-law samples across cities different at p<0.05;

pre-law samples across cities different at p<0.01;

pre-law samples across cities different at p<0.001;

post-law samples across cities different at p<0.05;

post-law samples across cities different at p<0.01;

post-law samples across cities different at p<0.001;

samples within cities different at p<0.05;

samples within cities different at p<0.01;

samples within cities different at p<0.001

Participants successfully followed for Mexico City (n=204), Guadalajara (n=241), Tijuana (n=149), and Ciudad Juárez (n=147)

Smoke-free campaign exposure

Figure 1 shows the crude prevalence estimates of self- reported exposure within the previous six months to a smoke-free media campaigns via four separate media channels. Assessments of the statistical significance of changes within and differences across cities involved adjustment for socio-demographics and current smoking status. Only in Mexico City did the prevalence of exposure increase significantly across all four media channels, and the post-law prevalence estimate was 68% to 88% for each channel assessed. When assessing exposure to smoke-free television ads, the proportional increase in Mexico City (44% to 88%) was greater than changes found in all other cities, and only Guadalajara had a comparably high prevalence at the post-law assessment (i.e., 83%). Similar results were found for exposure to smoke-free campaigns heard through the radio, except that post-law exposure was significantly higher in Mexico City than in Guadalajara (i.e., 70% and 59%, respectively). Regarding exposure to smoke-free campaign print materials, whether through newspaper and magazines or billboards and posters, Mexico City was the only city with significantly increased exposure. This increase was significantly greater and the post-law estimate higher than in all other cities.

Figure I.

Exposure in previous six months to smoke-free campaigns through distinct media channels by city, 2007 and 2008*

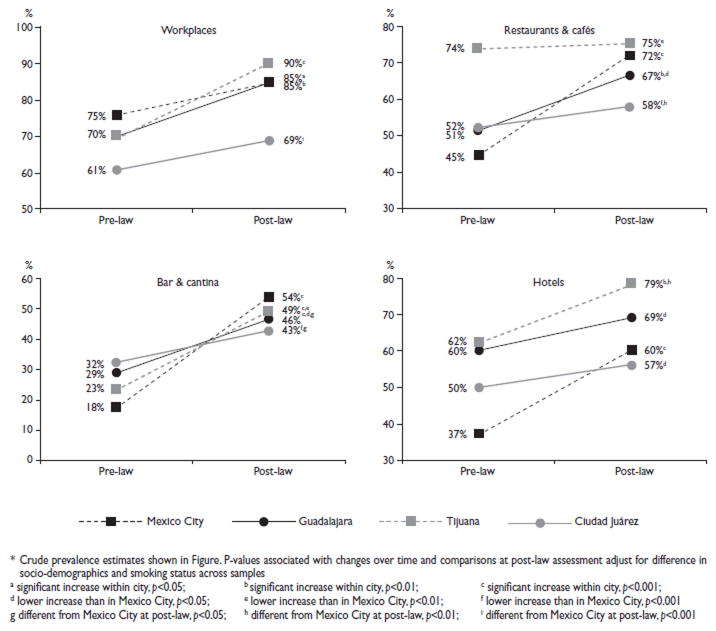

Support for smoke-free policies

Crude prevalence of support for smoke-free policies in a variety of venues was estimated for each city pre- and post-law (Figure 2). Tests for differences in support for smoke-free policies were assessed both within and across cities while controlling for socio-demographics and current smoking status. In general, support increased across all venues in all cities, except in Ciudad Juárez, where point estimates suggested a tendency toward increasing support within all venues, but which never reached statistical significance. Across all venues, support for smoke-free policies increased at a significantly faster rate in Mexico City than in Ciudad Juárez; except for the case of smoke-free hotels, the adjusted prevalence of support at post-law was significantly higher in Mexico City. With regard to smoke-free workplaces, support in Mexico City increased at a similar rate as in Guadalajara and Tijuana, and all three had a similarly high prevalence of support at the post-law assessment (range 85% to 90%).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of support for smoke-free policies in regulated venues by city, 2007 and 2008*

Support for smoke-free restaurants increased at a faster rate in Mexico than in these other two cities; however, the post-law prevalence of support was similar (range 67% to 75%). Support in Tijuana was high before the law (74%) and did not change (75%). Support for smoke-free bars increased more rapidly in Mexico City (18% to 54%) than in the other cities, resulting in higher support in Mexico City at follow-up as compared to Guadalajara or Ciudad Juárez (46% and 43%, respectively). Finally, support for smoke-free hotels increased at similar rates in Mexico City and in Tijuana over the study period, with no significant increase found in Guadalajara or Ciudad Juárez. At the post-law assessment, the prevalence of support for smoke-free hotels was significantly higher in Tijuana compared to Mexico City (i.e., 79% vs 60%, respectively).

Self-reported second-hand smoke exposure

The crude prevalence of self-reported SHS exposure was also estimated (Figure 3), with assessments of change over time and differences between cities determined after adjustment for socio-demographics and smoking status. Prevalence of self-reported smoking within private workplaces was assessed only among people who reported working in enclosed workplaces. Self- reported SHS exposure inside of enclosed workplaces in the previous month decreased significantly in Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Tijuana, but not in Ciudad Juárez. Only Tijuana had a significantly different prevalence of self-reported workplace SHS exposure at follow-up when compared to Mexico City (3% vs. 25%, respectively). Self-reported SHS exposure at the last visit to restaurants and cafés, as well as in bars and cantinas, decreased at a faster rate in Mexico City (i.e., 75% to 5% and 100% to 31%, respectively) than in the other cities. The post-law prevalence of self-reported SHS in bars and cantinas was significantly lower in Mexico City than in all three other cities; however, the post-law prevalence in restaurants and cafés was lower in Mexico City (5%) than in Guadalajara (45%), but not Tijuana or Juárez. Mexico City was the only city to experience statistically significant declines in self-reported SHS exposure in fondas during the study period (46% to 5%).

Figure 3.

Secondhand smoke exposure across different regulated venues by city, 2007 and 2008*

Discussion

Our results are generally consistent with other studies that indicate support for smoke-free policies increases after smoke-free laws are implemented,7–11 even among smokers.7,9,10,12,13 In our study, support for smoke–free laws increased over the study period, although support for smoke-free restaurants, cafés, bars and cantinas, increased at a faster rate in Mexico City than in other cities. This may be partly because Mexico City implemented a 100% smoking ban in all indoor workplaces and public places, whereas other cities were subject to the more ambiguous federal smoke-free law. Although federal and state authorities tried to communicate to the public that smoking was banned in all the same venues until regulations were developed to define designated smoking areas, this ambiguity appears to have invited some laxity in implementation of this temporary measure. Significant decreases in self-reported SHS exposure within these same venues were greater in Mexico City than in other cities, as well. These results lend support to the contention that the 100% smoke-free law in Mexico City was accompanied by changes in attitudes and reductions in self-reported SHS exposure that were above and beyond what would have happened if Mexico City was subject to federal law.21 Furthermore, study results indicated significant increases and higher overall exposure to smoke-free mass media campaigns through all channels in Mexico City, which suggests that media campaigns there helped shift social norms in favor of smoke-free environments.22,29,* Increases in the prevalence of exposure to SHS campaigns through radio and television were also found for Guadalajara, suggesting that the federal campaign primarily reached that market but not Tijuana or Juárez.

The federal smoke-free law, particularly in Guadalajara and Tijuana, was accompanied by important decreases in self-reported SHS and increases in support for smoke-free policies. These findings are noteworthy because the entry into force of the federal law appears to have influenced attitudes and behaviors in these cities, in spite of any confusion about the status of the law before smoke-free regulations were published. Some of the changes found in Guadalajara may be due to higher exposure to radio and television smoke-free campaigns, which were aired to support the federal law. Nevertheless, self-reported SHS exposure in bars and cantinas were still high (73% in Juárez to 93% in Guadalajara). Non-compliance was also highest in these venues for Mexico City (31%), for which other surveys provide estimates from smokers and non-smokers that are consistent with these.21 Also, the prevalence of self- reported SHS exposure within workplaces was generally similar across all cities (15% to 30%) except Tijuana (3%). Furthermore, self-reported workplace SHS exposure decreased dramatically in Guadalajara and Tijuana while remaining stable in Mexico City. To improve compliance, media campaigns and governmental efforts may require publicizing the punishment of all types of non-compliant workplaces, including those that are not within the hospitality sector. Such efforts are likely to benefit from the momentum of growing support for smoke-free policies across all segments of the Mexican population.

Study results for the US border town of Tijuana confirm previous studies suggesting the influence of tourism and associated secular influences from California,36 which has prohibited smoking in restaurants and bars for over a decade. Indeed, our data from before the federal law took effect indicate that support for smoke- free restaurants and cafés was substantially higher in Tijuana than in other Mexican cities (74% vs 45%–52%) and that self-reported SHS exposure in these venues was much lower (29% vs 56% to 75%). On the other hand, smoke-free El Paso, Texas,37 does not appear to have influenced Ciudad Juárez as much.

This study has some limitations that should temper our conclusions. The study samples were not entirely equivalent either across cities or within cities over time. However, our analyses involved statistical controls for measured differences; because most of our analytic sample comprised data from re-interviewed individuals, our analyses included some additional controls for un- measured variables. Nevertheless, cities showed differential attrition rates, which may have influenced results even though those lost to follow up were generally not significantly different from those who were followed up. Our use of a replenishment sample may not have sufficiently addressed any issues introduced by attrition or its differential influence across cities. Furthermore, those who participated may have differed in important ways from those who did not participate. Although participants may have been more favorable to tobacco control policy than the general population, we did not collect data from nonparticipants and cannot determine the directionality of selection bias. Our results, however, are consistent with other survey research conducted in Mexico City,21 and sample characteristics are consistent with those from the 2008 administration of the Encuesta Nacional de Ingreso y Gasto de los Hogares, suggesting the external validity of the results. Finally, post-test analysis occurred shortly after the smoke-free policies took effect but prior to the publication of the federal smoke-free regulations; hence, some of the changes found in Guadalajara, Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez may be due to secular trends that were under way before the federal law was passed. Further research is necessary to understand the impact of these regulations, which allow for smoking in designated areas.

Overall, this study provides evidence that smoke-free policies can work in middle-income countries. Comprehensive smoke-free policies that prohibit smoking in all enclosed workplaces, including restaurants and bars, appear acceptable to smokers, whose acceptance may be bolstered by media campaigns that remind them of the benefits of these laws for others. Indeed, comprehensive smoke-free policies not only appear to do a better job of decreasing toxic SHS exposure, but they also appear to be accompanied by greater increases in support and normative shifts that provide the foundation for other tobacco control policies which, over the long term, decrease tobacco consumption and tobacco-related disease.38

Acknowledgments

Funding for data collection on this study came from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT Convocatoria Salud-2007-C01-70032), as well as a project funded by the Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (Mexico 1-06). Analysis and writing of the ar- ticle was also funded by CONACyT and the National Cancer Institute (P01 CA138389), with additional funding provided by an unrestricted grant from Johnson & Johnson. Dr Ernesto Sebrié was supported by the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI).

Footnotes

Thrasher JF, Huang L, Pérez-Hernández R, et al. Porque todos respiramos los mismo: Evaluation of a social marketing campaign to support Mexico City’s comprehensive smoke-free law. Am J Public Health. Forthcoming

Conflict of Interest: None

Declaration of conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.WHO. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, Tobacco Free Initiative; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brownson RC, Hopkins DP, Wakefield M. Effects of smoking restrictions in the workplace. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:333–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Effect of smoke-free policies on smoking behavior:A systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7357):188. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasserman J, Manning WG, Newhouse JP, Winkler JD. The effects of excise taxes and regulations on cigarette smoking. J Health Econ. 1991;10(1):43–64. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90016-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson PD, Zapawa LM. Clean indoor air restrictions. In: Rabin RL, Sugarman SD, editors. Regulating tobacco. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 207–244. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton WL, Biener L, Brennan RT. Do local tobacco regulations influence perceived smoking norms? Evidence from adult and youth surveys in Massachusetts. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(4):709–22. doi: 10.1093/her/cym054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards R, Thomson G, Wilson N, Waa A, Bullen C, O’Dea D, et al. After the smoke has cleared: Evaluation of the impact of a new national smoke- free law in New Zealand. Tob Control. 2008;17(1):1–10. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorini G, Chellini E, Galeone D. What happened in Italy? A brief summary of studies conducted in Italy to evaluate the impact of the smoking ban. Annals of Oncology. 2007;18(10):1620–1622. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang H, Cowling D, Lloyd J, Rogers T, Koumjian K, Stevens C, et al. Changes of attitudes and patronage behaviors in response to a smoke- free law. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:611–617. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friss RH, Safer AM. Analysis of responses of Long Beach, California residents to the smoke-free bars law. Public Health. 2005;119:1116–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rayens M, Hahn E, Langley R, Hedgecock S, Butler K, Greathouse-Maggio L. Public opinion and smoke-free laws. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2007;8(4):262–270. doi: 10.1177/1527154407312736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong GT, Hyland A, Borland R, Hammond D, Hastings G, McNeil AD, et al. Reductions in tobacco smoke pollution and increases in support for smoke-free public places following the implementation of comprehensive smoke-free workplace legislation in the Republic of Ireland: Findings from the ITC Ireland/UK survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Sup 3):iii51–iii58. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyland A, Higbee C, Borland R, Travers M, Hastings G, Fong GT, et al. Attitudes and beliefs about secondhand smoke and smoke-free policies in four countries: Findings from the International Tob Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(6):642–649. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biener L, Garrett C, Skeer M, Siegel M, Connolly G. The effects on smokers of Boston’s smoke-free bar ordinance:A longitudinal analysis of changes in compliance, patronage, policy support and smoking at home. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(6):630–636. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000296140.94670.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sebrié EM, Schoj V, Glantz SA. Smoke free environments in Latin America: On the road to real change? Prev Control. 2008;3:21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.precon.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Thrasher JF, Chaloupka F, Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, Hastings G, et al. Evaluación de las políticas contra el tabaquismo en países latinoamericanos en la era del Convenio Marco para el Control del Tabaco [Evaluation of tobacco control policies in Latin American countries during the era of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control] Salud Publica Mex. 2006;48(Supp 1):S155–S166. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342006000700019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thrasher JF, Boado M, Sebrié EM, Bianco E. Smoke-free policies and the social acceptability of smoking in Uruguay and Mexico: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:591–599. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thrasher JF, Besley JC, González W. Perceived justice and popular support for public health laws:A case study around comprehensive smoke-free legislation in Mexico City. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:787–793. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abundis F. La Ley General de Control del Tabaco y la opinión pública [The General Law of Tobacco Control and public opinion] Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50(Supp 3):S366–S371. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000900014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thrasher JF, Bentley ME. The meanings and context of smoking among Mexican university students. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(5):578–585. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thrasher JF, Pérez-Hernández R, Swayampakala, et al. Translating the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Policy support, norms, and secondhand smoke exposure before and after implementation of a comprehensive smoke-free policy in Mexico City. Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180950. Epub 2010 May 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Villalobos V, Ortiz-Ramirez O, Thrasher JF, et al. Mercadotecnia social para promover políticas públicas de salud: El desarrollo de una campaña para promover la norma social de no fumar en restaurantes y bares del Distrito Federal, México. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(suppl 2):S127–S135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skeer M, Land ML, Cheng DM, Siegel MB. Smoking in Boston bars before and after a 100% smoke-free regulation:An assessment of early compliance. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10(6):501–507. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haw SJ, Gruer L. Changes in exposure of adult non-smokers to secondhand smoke after implementation of smoke-free legislation in Scotland: National cross-sectional survey. BMJ. 2007;335(335):549–552. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39315.670208.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akhtar P, Currie D, Currie C, Haw S. Changes in child exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (CHETS) study after implementation of smoke-free legislation in Scotland: National cross-sectional survey. BMJ. 2007;335:545. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39311.550197.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thrasher JF, Reynales-Shigematsu L, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Villalobos V, Téllez-Girón P, Arillo-Santillán E, et al. Promoting the effective translation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control:A case study of challenges and opportunities for strategic communications in Mexico. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31(2):145–166. doi: 10.1177/0163278708315921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sussman S, Pokhrel P, Black D, Kohrman M, Hamann S, Vateesatokit P, et al. Tobacco control in developing countries:Tanzania, Nepal, China, and Thailand as examples. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(3):S447–S457. doi: 10.1080/14622200701587078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navas-Acien A, Valdés-Salgado R. Niveles de nicotina en el ambiente de lugares públicos y de trabajo del Distrito Federal. In: Valdés Salgado R, Lazcano-Ponce EC, Hernández-Avila M, editors. Primer informe sobre el combate al tabaquismo. Cuernavaca, Morelos: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2005. pp. 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- 28.González-Roldan JF. Abogacía para el control del tabaco en México: Retos y recomendaciones. Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50(Supp 3):S391–S400. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000900017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mondragón y Kalb M. Prohibición de fumar en lugares públicos y mercantiles: Retos para implementar la ley en el Distrito Federal. Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50(Supp 3):S401–S404. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000900018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guillermo-Tenorio X. Expacios 100% libres de humo: una realidad del Distrito Federal. Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50(Supp 3):S384–S390. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000900016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Llaguno-Aguilar SE, Dorantes-Alonso AC, Thrasher JF, Villalobos V, Besley JC. Análisis de la cobertura del tema de tabaco en medios impresos mexicanos [Analysis of the coverage of tobacco in Mexican print media] Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50(Supp 3):S348–S354. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000900012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, Hastings G, Hyland A, Giovino GA, et al. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project. Tob Control. 2006;15(Supp 3):iii3–iii11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of health surveys. New York: Wiley- Interscience; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34.IARC. Methods for Evaluating Tobacco Control Policies. Vol. 12. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2009. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention:Tobacco Control. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martínez-Donate AP, Hovell MF, Hofstetter CR, González-Pérez GJ, Kotay A, Adams MA. Crossing borders: the impact of the California. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tobacco Control Program on both sides of the US-Mexico border. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):258–267. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds JH, Hobart RL, Ayala P, Eischen MH. Clean indoor air in El Paso,Texas: a case study. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1):A22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alamar B, Glantz SA. Effect of increased social unacceptability of cigarette smoking on reduction in cigarette consumption. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1359–1363. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]