Abstract

Complementary to parameters established for cell-adhesion force curve analysis, we evaluated the slope before a force step together with the distance from the surface at which the step occurs and visualized the result in a two-dimensional density plot. This new tool allows detachment steps of long membrane tethers to be distinguished from shorter jumplike force steps, which are typical for cytoskeleton-anchored bonds. A prostate cancer cell line (PC3) immobilized on an atomic-force-microscopy sensor interacted with three different substrates: collagen-I (Col-I), bovine serum albumin, and a monolayer of bone marrow-derived stem cells (SCP1). To address PC3 cells’ predominant Col-I binding molecules, an antibody-blocking β1-integrin was used. Untreated PC3 cells on Col-I or SCP1 cells, which express Col-I, predominantly showed jumps in their force curves, while PC3 cells on bovine-serum-albumin- and antibody-treated PC3 cells showed long membrane tethers. The probability density plots thus revealed that β1-integrin-specific interactions are predominately anchored to the cytoskeleton, while the nonspecific interactions are mainly membrane-anchored. Experiments with latrunculin-A-treated PC3 cells corroborated these observations. The plots thus reveal details of the anchoring of bonds to the cell and provide a better understanding of receptor-ligand interactions.

Main Text

Atomic-force-microscopy-based, single-cell force spectroscopy is widely used to study cell mechanics and cell adhesion (1). Environmental changes influencing the cellular behavior are frequently in focus during such investigations (2–4). Force distance curves from single-cell force spectroscopy contain far more information than just absolute force values, and moreover, quantify the underlying molecular interactions of cell surface receptors with their respective substrates (5); the receptors are embedded in a complex cellular environment, and the force distance curves also contain valuable information about the anchoring of the receptors to the plasma membrane or the cytoskeleton.

Here we have investigated the interaction between the prostate cancer cell line (PC3) and collagen (Col-1) (Fig. 1) as well as monolayers of the Col-I-expressing mesenchymal stem cell line (SCP1) (see the Supporting Material and Sariisik et al. (6) for experimental details). Because quantitative polymerase chain reaction revealed high expression levels of the collagen binding integrins α1β1 and α2β1 in PC3 cells (0.08 ± 0.01 and 0.31 ± 0.1-fold of the GADPH expression; see Popov et al. (7) for details), we used a β1-integrin blocking antibody (monoclonal antibody to CD29; Acris Antibodies, San Diego, CA) to identify the specific contribution of these integrins. A bovine serum albumin (BSA)-coated surface and latrunculin-A-treated PC3 cells were used as additional negative controls (7).

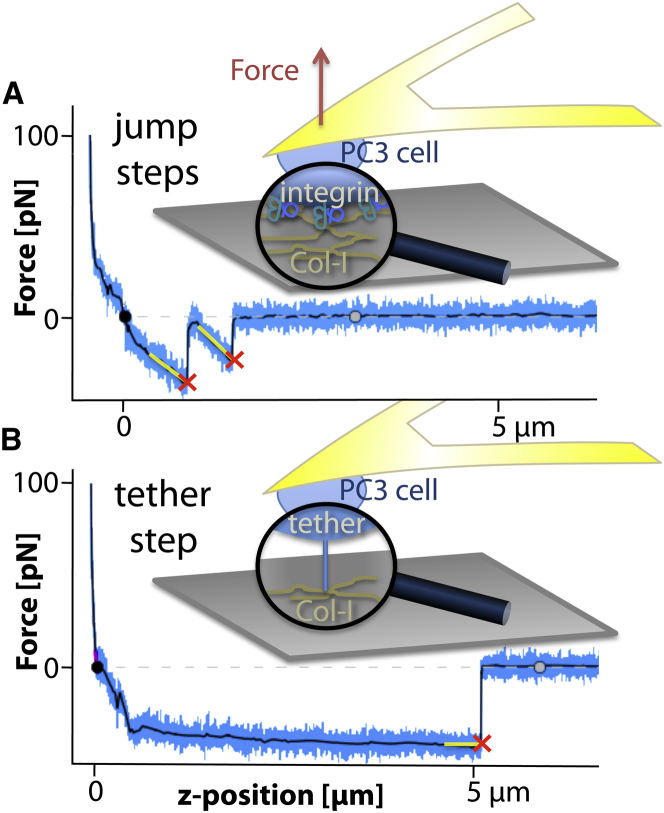

Figure 1.

Two force traces of a PC3 cell separated from a Col-I substrate at a velocity of 3 μm/s after contacts of 0.3 s at 100 pN. (Crosses) Steps. (Black line) Smoothed force trace. A line-fit indicates the slope before a step. (A) Jumplike steps were defined at slopes <−10 pN/μm. (B) Tetherlike steps, caused by membrane tubes pulled from the cell by bonds not anchored to the cytoskeleton, typically show slopes of 0 ± 10 pN/μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

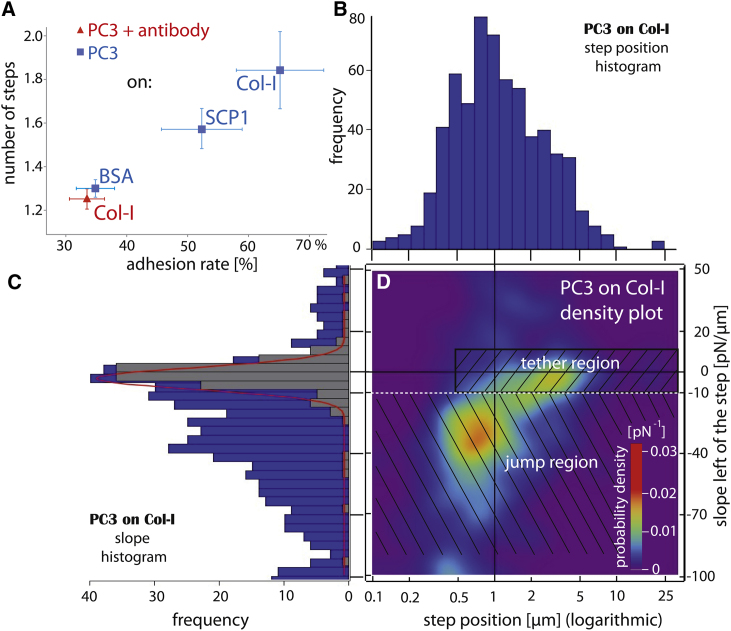

To begin, the commonly derived parameters to quantify cell adhesion—the adhesion rate, the number of steps per curve, the detachment force, the dissipated work, and the step height—were analyzed (see Benoit and Selhuber-Unkel (8) and the Supporting Material). On Col-I-coated surfaces and on the SCP1 monolayer, the adhesion rate and the number of steps are found to be significantly higher than on BSA-coated surfaces, where both parameters are in the same range as for the antibody-treated PC3 cells (see Fig. 2 A). The same trend can be observed for the detachment force and dissipated work, while the step height shows much less variation (data not shown). However, despite a clear difference in four of the parameters quantifying the interactions, no information about the type of interaction—and in particular about the anchoring of the relevant receptors to their respective microenvironment—can be obtained from any of these parameters alone. To gain more detailed insight into the receptor anchoring to the cell membrane or cytoskeleton, we extracted two additional parameters from the data and displayed them in normalized two-dimensional probability density maps: the position of detachment force steps (distance from the contact point), and the slope before each step.

Figure 2.

(A) Number of steps versus adhesion rate reveals that PC3 cells after antibody treatment interact nonspecifically, like on BSA. For each probed interaction, 10 different cells with at least 100 force traces each were measured. Standard errors are given as error bars. (B) Histogram of the step positions and (C) corresponding slopes of untreated PC3 cells on collagen substrate. (Gray subsection) Membrane tethers (Gaussian fitted on top). (D) A smoothed two-dimensional probability density plot of the slope versus step position reveals cumulated jumps and a few longer tethers. (Black lines) Zero slope and 1 μm step position. (White line at −10 pN/μm) Apparent best border between tether region and jump region. (Inset, colored bar codes for the probability densities.) To see this figure in color, go online.

Interactions involving receptors linked to the cytoskeleton typically exhibit a clear rise in force just before the unbinding event, like in the force curve displayed in Fig. 1 A (2). On the other hand, long plateaus with slopes around zero, as displayed in Fig. 1 B, are typical of tethers being pulled out of the cell membrane. Here the constant force before the unbinding event is caused by the constant tension of the plasma membrane (8–10).

We evaluated the step position using the step detection algorithm developed by Opfer and Gottschalk (11) and the slope using a linear fit starting 500 nm before each force step (6). Fig. 2, B and C, shows histograms of the position and slope. In Fig. 2 D, both parameters are combined in a color-coded, two-dimensional probability density plot (i.e., the two-dimensional plot). As can be seen from this two-dimensional plot of PC3 cells on Col-I, there are two distinct regions: one at step positions between 0.5 and 1 μm and slopes at ∼−30 pN/μm, pointing to membrane-linked cellular receptors; and a second one at ∼3 μm and slopes close to 0 pN/μm, which represents membrane tethers.

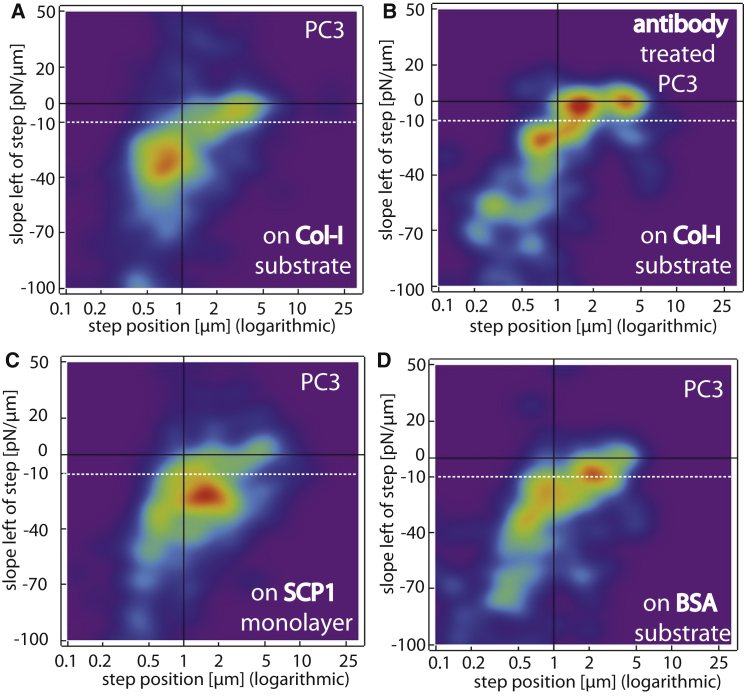

Fig. 3 shows slope-versus-step-position plots of interactions of PC3 cells (and antibody-treated PC3 cells) with Col-I- and BSA-coated substrates as well as with SCP1 monolayers. As already mentioned, on the Col-I-coated substrate (Fig. 3 A is identical to Fig. 2 D), there are two distinct peaks—one that resembles interactions of cytoskeleton-linked receptors (jumps), and one that resembles membrane tethers. Without antibody blocking of β1-integrin, the majority of interactions are clearly jumplike. If the PC3 cells are incubated with an anti-β1 antibody (Fig. 3 B), the majority of interactions shift to the tether region of the plot. Similarly, if the cells are treated with latrunculin-A, a drug that disrupts the actin cytoskeleton by blocking G-actin, virtually all interactions are shifted to the tether region (see Fig. S1).

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional probability density plots of PC3 cells interacting specifically with Col-I (A) and SCP1 cells (C) and nonspecifically with BSA (D). (B) PC3 cells treated with monoclonal antibody to CD29/integrin β1 also interact nonspecifically with Col-I (see Fig. 2D for color-coding of the probability densities). To see this figure in color, go online.

In contrast to the Col-I substrate, PC3 cells probed on the SCP1 substrate show fewer tethers and densely cumulate their jumplike steps at −30 pN/μm and a distance of ∼1.7 μm. This shift to higher step positions reflects the mechanical properties of the softer SCP1 cell layer compared to the stiff Col-I-coated substrate (compare the parts of Fig. 3, A and C). The reduced number of tethers indicates an increased coupling of receptors to the cytoskeleton on the SCP1 substrate compared to the collagen substrate. This may reflect an optimized accessibility of receptor-ligand pairs between interacting cells, as well as an effective suppression of nonspecific interactions compared to the collagen-coated glass substrates (12).

Finally, on BSA-coated substrates, the adhesion rate and number of steps is significantly lower (Fig. 2 A), as can be expected for a substrate allowing only nonspecific interactions. Accordingly, the initial jump population (Fig. 3 A) is shifted toward tethers, and only a few jumps remain (Fig. 3 D).

In summary, the slope position density plots help to visualize the embedding and anchorage of adhesion molecules in the cell. They reflect the substrate-dependent complex adhesion behavior of cells. In combination with results of complementing techniques, such as quantitative polymerase chain reaction and blocking experiments, their readout allows identification of the specificity of the cellular interaction in the slope-position plane and strengthens the interpretation of single-cell force spectroscopy data, in particular with respect to the anchoring of the receptors in the cell.

Author Contributions

E.S. performed the atomic-force-microscopy measurements and quantitative polymerase chain reaction work and evaluated the data together with J.P.M.; C.P. designed the quantitative polymerase chain reaction method and the cell treatments; D.D., H.C.-S., and M.B. designed the project and supervised the experiments; and H.C.-S. and M.B. wrote the article together with E.S.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erich Sackmann, Hermann Gaub, Stefanie Sudhop, and Michael Nash for helpful discussions, and Angelika Kardinal and Thomas Nicolaus for advice and support with the cell culturing.

We gratefully acknowledge financial support of the Ministry of National Education of Turkey, and of the German Excellence Initiative, via the Nanosystems Initiative Munich and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Editor: Andreas Engel.

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Supporting Materials and Methods and four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(15)00785-7.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Taubenberger A.V., Hutmacher D.W., Muller D.J. Single-cell force spectroscopy, an emerging tool to quantify cell adhesion to biomaterials. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2014;20:40–55. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2013.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedrichs J., Legate K.R., Benoit M. A practical guide to quantify cell adhesion using single-cell force spectroscopy. Methods. 2013;60:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celik E., Faridi M.H., Gupta V. Agonist leukadherin-1 increases CD11b/CD18-dependent adhesion via membrane tethers. Biophys. J. 2013;105:2517–2527. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamontagne C.-A., Cuerrier C.M., Grandbois M. AFM as a tool to probe and manipulate cellular processes. Pflüg. Arch. Eur. J. Phys. 2008;456:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helenius J., Heisenberg C.-P., Muller D.J. Single-cell force spectroscopy. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:1785–1791. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sariisik E., Docheva D., Benoit M. Probing the interaction forces of prostate cancer cells with collagen I and bone marrow derived stem cells on the single cell level. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popov C., Radic T., Docheva D. Integrins α2β1 and α11β1 regulate the survival of mesenchymal stem cells on collagen I. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e186. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benoit M., Selhuber-Unkel C. Measuring cell adhesion forces: theory and principles. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;736:355–377. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-105-5_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benoit M. Force spectroscopy on cells. In: Sattler K.D., editor. Handbook of Nanophysics: Nanomedicine and Nanorobotics. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2010. 9:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun M., Graham J.S., Grandbois M. Multiple membrane tethers probed by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2005;89:4320–4329. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Opfer J., Gottschalk K.-E. Identifying discrete states of a biological system using a novel step detection algorithm. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu C., Celik E., Moy V.T. Elongated membrane tethers, individually anchored by high affinity α4β1/VCAM-1 complexes, are the quantal units of monocyte arrests. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.