Abstract

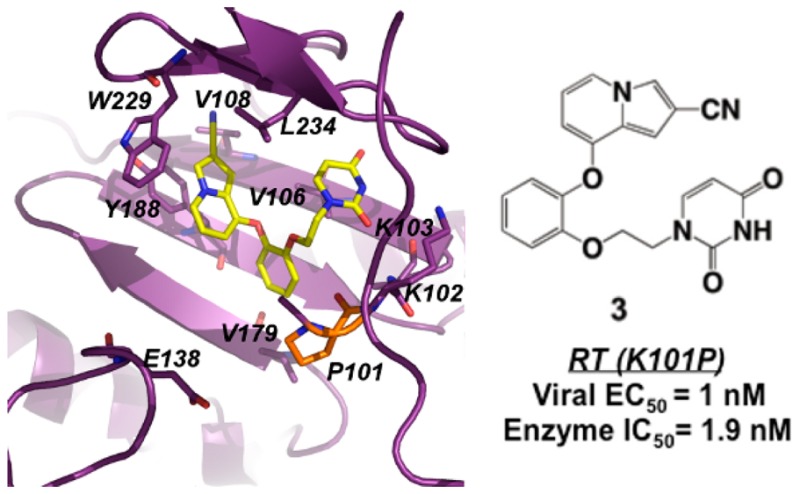

Catechol diether compounds have nanomolar antiviral and enzymatic activity against HIV with reverse transcriptase (RT) variants containing K101P, a mutation that confers high-level resistance to FDA-approved non-nucleoside inhibitors efavirenz and rilpivirine. Kinetic data suggests that RT (K101P) variants are as catalytically fit as wild-type and thus can potentially increase in the viral population as more antiviral regimens include efavirenz or rilpivirine. Comparison of wild-type structures and a new crystal structure of RT (K101P) in complex with a leading compound confirms that the K101P mutation is not a liability for the catechol diethers while suggesting that key interactions are lost with efavirenz and rilpivirine.

Keywords: HIV, reverse transcriptase, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, resistance, mutations

Despite the success of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for the treatment of HIV,1−3 resistance and suboptimal pharmacological properties of antiviral agents continue to limit the efficacy of current drug regimens.4,5 Due to the error prone nature of HIV replication,6,7 the predominant mechanism of resistance involves the selection of mutations in target enzymes HIV protease, integrase, and reverse transcriptase (RT).8−10 The majority of anti-HIV drugs target RT by binding to the polymerase site (nucleoside RT inhibitors or NRTIs) or an allosteric site known as the non-nucleoside binding pocket (non-nucleoside RT inhibitors or NNRTIs). Resistance-associated mutations (RAMs) within or near the non-nucleoside binding pocket reduce the potency of first generation NNRTIs such as efavirenz.9 Rilpivirine represents a new class of flexible diarylpyrimidne (DAPY) inhibitors that maintains activity against several RT resistant variants with K103N, Y181C, Y188L, and L100I mutations.11−13 As more combination treatments such as Complera14 include rilpivirine in antiretroviral regimens, less frequent variants of RT may emerge that contain mutations at the K101 position. These mutations include K101E, K101H, and K101P amino acid changes.5,15−18 While the K101E mutation emerges in the viral population at greater frequency, K101P confers much greater resistance.5 Specifically, RT variants with the K101P mutation are up to 243-fold less susceptible to rilpivirine and >50-fold less susceptible to efavirenz,10 a common NNRTI included in HAART regimen Atripla.14 Moreover, rilpivirine has additional pharmacological limitations in terms of poor solubility and virological failure associated with dose-limiting cardiotoxicity.19,20 As efavirenz and rilpivirine are widely used in HAART regimens, very few options regarding NNRTIs are available for patients suffering from virologic failure due to minority RAMs such as K101P in RT.

To design new inhibitors that are effective against several variants of RT while retaining good pharmacological properties, we have implemented a multidisciplinary approach to examine mutations such as K101P that confer resistance to rilpivirine. Previously we reported several kinetic, mechanistic, and structural studies on RT and a new class of non-nucleoside inhibitors known as the catechol diethers.21−25 In this study, we evaluated some of the leading catechol diether compounds, in terms of potency and solubility, against a panel of HIV strains containing RT variants with K101P, K103N, and Y181C mutations using a single round infectivity assay. Results from the assay reveal that our leading catechol diether compounds maintain potency for RT K101P variants, while rilpivirine resistance is reaffirmed as in earlier reported studies.5,10,15,17,26

In order to understand the effects of the K101P mutation, kinetic data for the RT (K101P) enzyme was evaluated and compared to the wild-type, RT (WT). We also obtained a cocrystal structure of RT (K101P) with a catechol diether, compound 3, to evaluate the binding interactions in the non-nucleoside pocket. To our knowledge, this is the first study that kinetically and structurally characterizes RT with the K101P mutation with regards to rilpivirine resistance and inhibitor development.

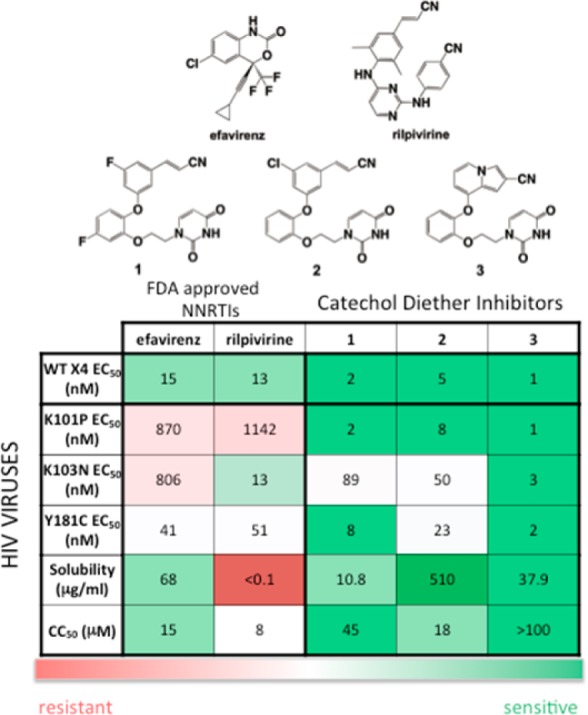

In pursuit of an inhibitor that maintains affinity against a panel of RT variants, a single infectivity assay was used to evaluate compounds 1, 2, 3, efavirenz, and rilpivirine for antiviral activity against a panel of RT variants (Figure 1). Compounds 1–3 were selected due to their high potency and good aqueous solubility (Figure 1).21,23,25 As reported in several studies,11,12,17 rilpivirine has an excellent resistance profile specifically for variants with K103N, Y181C, and L100I mutations. In the panel of variants tested in this study, rilpivirine retains potency for variants with K103N and Y181C mutations in the low to midnanomolar range; this is in agreement with previously determined antiviral data.11,12,21 However, the K101P mutation drastically affects rilpivirine potency, causing an 88-fold increase in EC50 compared to the wild-type (WT X4) strain. The K101P mutation also affects the potency of NNRTI efavirenz in which there is an observed 58-fold increase in EC50 compared to WT X4. Interestingly, both the rigid structure of efavirenz and more flexible DAPY structure of rilpivirine lose potency for RT variants containing the K101P mutation.

Figure 1.

Potency (EC50) and cytotoxicity (CC50) values for efavirenz, rilpivirine, and compounds 1–3 determined using a single-round infectivity assay. Solubility measurements are reported (in μg/mL) for each respective compound. EC50 values are reported in nM; CC50 values are reported in μM.

In evaluating the catechol diether compounds, 1–3 maintain efficacy for HIV variants containing the K101P mutation in the low nanomolar range with essentially no loss of potency compared to WT X4. In an improvement over the results from an MTT assay used previously,21,23,25 RT variants with Y181C are also susceptible to 1–3 in the low nanomolar range. Compounds 1 and 2 are less effective against variants containing the K103N mutation, whereas 3 retains potency 4-fold greater than rilpivirine. Our data reaffirms observations from several assays5,15,17,27 that reveal RT variants with K101P are resistant to rilpivirine. Thus, we were interested in characterizing the RT (K101P) enzyme kinetically and structurally to understand the effects of the K101P mutation, rilpivirine resistance, and the molecular mechanism by which catechol diether compounds retain potency.

RT variants with the K101P mutation are in low frequency in the HIV viral population compared to high frequency variants containing Y181C and K1013N mutations.5,10 However, we were compelled to characterize RT (K101P) with regards to enzyme fitness to perhaps understand why it appears less frequently in the viral population. To assess enzyme catalysis as an indication of fitness for RT (K101P) and RT (WT), we used presteady state kinetics to determine rates of deoxynucleotide incorporation, kpol (Table 1) and misincorporation (Table 2) opposite dT in the template as well as the dNTP affinity, Kd, and efficiency (kpol/Kd,). In terms of incorporation, RT (WT) and RT (K101P) utilize the correct incoming nucleotide (dATP) with similar catalytic efficiencies. These results suggest that, despite its low viral frequency, the K101P mutation does not compromise the polymerization capabilities of RT and that the RT (K101P) enzyme is just as catalytically fit as the RT (WT) enzyme. In terms of misincorporation, RT (K101P) is more efficient in incorporating an incorrect deoxynucleotide (dGTP) than RT (WT) (Tables 1 and 2). More strikingly, there is a 12-fold reduction in RT (K101P) fidelity compared to RT (WT) (Table 2). The K101P mutation seems to enhance misincorporation, and this results in an RT enzyme that is more error prone and likely to generate new mutations in the viral genome.

Table 1. Kinetic Characterization of Correct Incorporation of dATP for RT (WT) and RT (K101P).

| Kd dATP (μM) | kpol dATP (s–1) | efficiency (kpol/Kd; s–1 μM–1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT (WT) | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 14 ± 2 | 6.4 ± 2.7 |

| RT (K101P) | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 25.3 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

Table 2. Kinetic Characterization of dGTP Misincorporation Opposite dT for RT (WT) and RT (K101P).

To complement the antiviral data, we used a PicoGreen fluorescence assay to examine the inhibition of reverse transcription. IC50 values were determined for rilpivirine and compounds 1–3 using methods described previously.22,28 Activity and inhibition assays were determined for both RT (WT) and RT (K101P) enzymes. IC50 values for both RT (WT) and RT (K101P) are similar to the EC50 values determined for the WT X4 and K101P strains in the single infectivity assay. Compounds 1–3 have IC50 values in the low nanomolar range for both RT variants. For compounds 1–3, there is a minimal fold-change in potency ranging from 0.6 to 1.8, whereas the potency of rilpivirine is reduced by 67-fold for RT (K101P) (Table 3). Compelled by the antiviral and enzyme inhibition data, structural analysis was pursued to understand binding interactions and to determine a potential mechanism of resistance caused by the K101P mutation.

Table 3. Inhibition Data (IC50 in nM) for Rilpivirine and Compounds 1–3 Determined Using PicoGreen Fluorescence Assay.

| rilpivirine | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT (WT) | 15 ± 3 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 1.06 ± 0.08 |

| RT (K101P) | 1000 ± 200 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

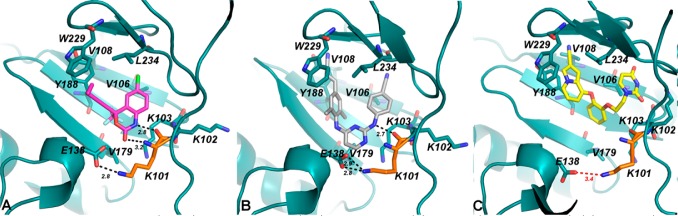

Wild-type structures for RT in complex with efavirenz, rilpivirine, and all three catechol diether compounds 1–3 are currently available.11,22,24,25,29 In analyzing the wild-type structures, we examined the binding interactions of efavirenz, rilpivirine, and compound 3 (our most potent representative of the catechol diether inhibitors) specifically with K101 (Figure 2C). In both efavirenz and rilpivirine structures (Figure 2A,B), a salt bridge is apparent between E138 (p51 subunit of RT) and K101 (p66 subunit of RT). This salt bridge is located at the rim of the binding pocket for both efavirenz and rilpivirine. Interestingly, this salt bridge seems to stabilize the positioning of the K101 backbone in order to make either two hydrogen bonds with efavirenz (Figure 2A) or one hydrogen bond with rilpivirine (Figure 2B). In contrast, compound 3 binds further away from both K101 and E138, and the salt bridge is weaker (in terms of distance of ion pairs). Compound 3 does not form any hydrogen bonds with K101 and is farther away from the rim of the pocket (Figure 2C). Based on this analysis, we hypothesized that the amino acid change from lysine to proline at position 101 would affect crucial interactions with efavirenz and rilpivirine, while not affecting compounds 1–3.

Figure 2.

Comparison of K101 (orange) interactions for RT (WT) in complex with (A) efavirenz (PDB code: 1FK9), (B) rilpivirine (PDB code: 2ZD1), and (C) compound 3 (PDB code: 4MFB). Compound 3 binds farther away from the E138-K101 salt bridge and does not interact with K101.

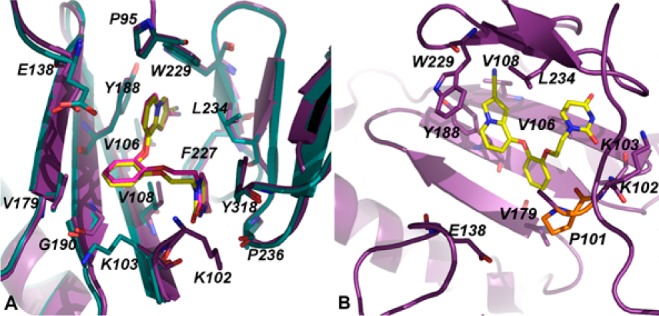

A cocrystal structure of the RT (K101P):3 complex reveals that the compound can accommodate the non-nucleoside binding pocket and bind in a similar orientation as in the RT (WT) structure (Figure 3A). In fact, the residues within the RT (WT) with RT (K101P) binding pocket superimpose with an rmsd of only 0.419 Å. P101 does not appear to be interacting with compound 3 since the compound binds deeper into the tunnel region of the pocket (Figure 3B). As speculated by the analysis of the wild-type structures, K101 does not interact with 3, but instead makes several van der Waals interactions with residues in the pocket such as P95, V106, V108, V179, Y188, F227, W229, L234, and Y318. This suggests that the proline substitution does not affect the binding of 3 and the other catechol diether compounds. As confirmed by the antiviral and inhibition data, the K101P mutation reduces efavirenz and rilpivirine susceptibility. In agreement with this data we were not able to cocrystallize efavirenz or rilpivirine with RT (K101P), likely due to the low binding affinity between the NNRTI binding pocket and the inhibitors. By extension of the structural analysis, the reliance of K101 for salt bridge stabilization and direct backbone hydrogen bonding may contribute to the high level resistance observed for rilpivirine and efavirenz with K101P RT variants.

Figure 3.

(A) Superposition of the RT (WT):3 (teal, 3 = pink) and RT (K101P):3 (purple, 3 = yellow) complexes. Compound 3 adopts the same orientation in both RT (WT) and RT (K101P) structures. (B) Representation of the RT (K101P):3 structure with respect to the location of P101 and E138. A salt bridge between E138 and P101 cannot be formed in the RT (K101P) structure suggesting that this lost interaction would most likely affect the binding of efavirenz and rilpivirine.

In parallel to the single-infectivity assays, we have also examined compounds 2 and 3 against RT variants with E138K and E138K/M184V RAMs in an MTT assay for antiviral activity (Table S2). Compounds 2 and 3 are extraordinarily potent for E138K, with EC50 values of 2.8 nM and 900 pM, respectively. For RT variants with E138K/M184V, similar EC50 values are observed with 2.2 nM (2) and 750 pM (3). Complementary to our analysis of the RT (K101P) structure, the antiviral data for E138K variants suggest that disruption of the E138-K101 salt bridge has little effect on catechol diether potency. Interestingly, E138K is not only a key residue for salt bridge stabilization, as observed in the efavirenz and rilpivirine RT (WT) structures, but it is also the most common RAM identified in patients receiving rilpivirine combination therapies.30

In summary, the catechol diether compounds were evaluated against a panel of RT variants. Compounds 1–3 emerge as potent inhibitors of HIV strains containing RT (K101P) variants, and the enzyme inhibition data correlates well with this discovery. In characterizing the enzyme kinetically, we found that the RT (K101P) variant is just as catalytically fit as RT (WT) but has reduced fidelity. However, this data only describes the catalytic fitness of RT (K101P) relative to RT (WT) and does not account for viral replication capacity. Future experiments can be used to evaluate viral fitness31 in the context of RT (K101P) and whether this directly correlates with enzymatic catalytic fitness. Despite its low frequency to date in clinically isolated strains, RT (K101P) variants have high-level resistance to both efavirenz and rilpivirine, the two major NNRTIs used in HAART combination therapies. Analysis of the current wild-type structures for efavirenz, rilpivirine, and 3 reveal that the latter inhibitor does not rely on a key hydrogen bond with K101. A crystal structure of RT (K101P) in complex with 3 reveals that the P101 mutation does not interact with 3 nor does this mutation affect compound binding relative to the wild-type structure. The catechol diether compounds can be developed as effective non-nucleoside inhibitors targeting RT variants with minority RAM K101P, in addition to E138K, in the case of increasing treatment failure of DAPY inhibitors such as rilpivirine due to high-level resistance.

Acknowledgments

Additional gratitude is expressed to Yale University for the Gruber Fellowship (WTG). We also thank the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) for beam time on X29A. Sincerest thanks to Professor Mark A. Wainberg and Dr. Hong-Tao Xu for sharing viral plasmids containing RT E138K and E138K/M184V.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- NRTI

nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- NNRTI

non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- RAMs

resistance-associated mutations

- WT

wild-type

- K101P

lysine to proline amino acid change at position 101 of RT

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00254.

Materials and methods, data collection and refinement statistics for the RT (K101P):3 structure, and electron density maps (PDF)

Accession Codes

The RT (K101P):3 complex is deposited as an entry in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 5C42.

Author Contributions

⊥ Authors contributed equally to this work. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Gratitude is expressed to the National Institutes of Health for research support (AI44616, GM49551), fellowship support for K.M.F. (AI104334), training support for W.T.G. (GM007499, GM007324), and training support for A.C.M. (GM007324).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- de Bethune M. P. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), their discovery, development, and use in the treatment of HIV-1 infection: a review of the last 20 years (1989–2009). Antiviral Res. 2010, 85, 75–90. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Clercq E. Anti-HIV drugs: 25 compounds approved within 25 years after the discovery of HIV. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2009, 33, 307–320. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pau A. K.; George J. M. Antiretroviral therapy: current drugs. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014, 28, 371–402. 10.1016/j.idc.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahchop E. L.; Wainberg M. A.; Sloan R. D.; Tremblay C. L. Antiviral drug resistance and the need for development of new HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 5000–5008. 10.1128/AAC.00591-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson A. E.; Rhee S. Y.; Parry C. M.; El-Khatib Z.; Charalambous S.; De Oliveira T.; Pillay D.; Hoffmann C.; Katzenstein D.; Shafer R. W.; Morris L. Impact of drug resistance-associated amino acid changes in HIV-1 subtype C on susceptibility to newer nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 960–971. 10.1128/AAC.04215-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston B. D.; Poiesz B. J.; Loeb L. A. Fidelity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science 1988, 242, 1168–1171. 10.1126/science.2460924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J. D.; Bebenek K.; Kunkel T. A. The Accuracy of Reverse-Transcriptase from Hiv-1. Science 1988, 242, 1171–1173. 10.1126/science.2460925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das K.; Arnold E. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and antiviral drug resistance. Part 2. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013, 3, 119–128. 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das K.; Arnold E. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and antiviral drug resistance. Part 1. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013, 3, 111–118. 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensing A. M.; Calvez V.; Gunthard H. F.; Johnson V. A.; Paredes R.; Pillay D.; Shafer R. W.; Richman D. D. 2014 Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top Antivir Med. 2014, 22, 642–650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das K.; Bauman J. D.; Clark A. D. Jr.; Frenkel Y. V.; Lewi P. J.; Shatkin A. J.; Hughes S. H.; Arnold E. High-resolution structures of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase/TMC278 complexes: strategic flexibility explains potency against resistance mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 1466–1471. 10.1073/pnas.0711209105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. C.; Pauly G. T.; Rai G.; Patel D.; Bauman J. D.; Baker H. L.; Das K.; Schneider J. P.; Maloney D. J.; Arnold E.; Thomas C. J.; Hughes S. H. A comparison of the ability of rilpivirine (TMC278) and selected analogues to inhibit clinically relevant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase mutants. Retrovirology 2012, 9, 99. 10.1186/1742-4690-9-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdon E. B.; Brendza K. M.; Hung M.; Wang R.; Mukund S.; Jin D.; Birkus G.; Kutty N.; Liu X. Crystal structures of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with etravirine (TMC125) and rilpivirine (TMC278): implications for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 4295–4295. 10.1021/jm1002233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Permpalung N.; Putcharoen O.; Avihingsanon A.; Ruxrungtham K. Treatment of HIV infection with once-daily regimens. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2012, 13, 2301–2317. 10.1517/14656566.2012.729040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng M.; Wang D.; Grobler J. A.; Hazuda D. J.; Miller M. D.; Lai M. T. In vitro resistance selection with doravirine (MK-1439), a novel nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor with distinct mutation development pathways. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 590–598. 10.1128/AAC.04201-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin N. T.; Gupta S.; Chappey C.; Petropoulos C. J. The K101P and K103R/V179D mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase confer resistance to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 351–354. 10.1128/AAC.50.1.351-354.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M.; Saravolatz L. D. Rilpivirine: a new non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 250–256. 10.1093/jac/dks404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamane M.; Varghese V.; Melikian G. L.; Fessel W. J.; Katzenstein D. A.; Shafer R. W. Panel of prototypical recombinant infectious molecular clones resistant to nevirapine, efavirenz, etravirine, and rilpivirine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4522–4524. 10.1128/AAC.00648-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozniak A. L.; Morales-Ramirez J.; Katabira E.; Steyn D.; Lupo S. H.; Santoscoy M.; Grinsztejn B.; Ruxrungtham K.; Rimsky L. T.; Vanveggel S.; Boven K. Efficacy and safety of TMC278 in antiretroviral-naive HIV-1 patients: week 96 results of a phase IIb randomized trial. AIDS 2010, 24, 55–65. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833032ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin A.; Pozniak A. L.; Morales-Ramirez J.; Lupo S. H.; Santoscoy M.; Grinsztejn B.; Ruxrungtham K.; Rimsky L. T.; Vanveggel S.; Boven K.; Group T. C. S. Long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rilpivirine (RPV, TMC278) in HIV type 1-infected antiretroviral-naive patients: week 192 results from a phase IIb randomized trial. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2012, 28, 437–446. 10.1089/AID.2011.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollini M.; Domaoal R. A.; Thakur V. V.; Gallardo-Macias R.; Spasov K. A.; Anderson K. S.; Jorgensen W. L. Computationally-guided optimization of a docking hit to yield catechol diethers as potent anti-HIV agents. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 8582–891. 10.1021/jm201134m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey K. M.; Bollini M.; Mislak A. C.; Cisneros J. A.; Gallardo-Macias R.; Jorgensen W. L.; Anderson K. S. Crystal structures of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with picomolar inhibitors reveal key interactions for drug design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 19501–19503. 10.1021/ja3092642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. G.; Frey K. M.; Gallardo-Macias R.; Spasov K. A.; Bollini M.; Anderson K. S.; Jorgensen W. L. Picomolar Inhibitors of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase: Design and Crystallography of Naphthyl Phenyl Ethers. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1259–1262. 10.1021/ml5003713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey K. M.; Puleo D. E.; Spasov K. A.; Bollini M.; Jorgensen W. L.; Anderson K. S. Structure-based evaluation of non-nucleoside inhibitors with improved potency and solubility that target HIV reverse transcriptase variants. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 2737–2745. 10.1021/jm501908a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. G.; Gallardo-Macias R.; Frey K. M.; Spasov K. A.; Bollini M.; Anderson K. S.; Jorgensen W. L. Picomolar inhibitors of HIV reverse transcriptase featuring bicyclic replacement of a cyanovinylphenyl group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16705–16713. 10.1021/ja408917n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiel C.; Schneider V.; Guessant S.; Hamidi M.; Kherallah K.; Lebrette M. G.; Chas J.; Lependeven C.; Pialoux G. Initiation of rilpivirine, tenofovir and emtricitabine (RPV/TDF/FTC) regimen in 363 patients with virological vigilance assessment in ’real life’. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 3335–3339. 10.1093/jac/dku294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picchio G. R.; Rimsky L. T.; Van Eygen V.; Haddad M.; Napolitano L. A.; Vingerhoets J. Prevalence in the USA of rilpivirine resistance-associated mutations in clinical samples and effects on phenotypic susceptibility to rilpivirine and etravirine. Antiviral Ther. 2014, 19, 819–823. 10.3851/IMP2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silprasit K.; Thammaporn R.; Tecchasakul S.; Hannongbua S.; Choowongkomon K. Simple and rapid determination of the enzyme kinetics of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and anti-HIV-1 agents by a fluorescence based method. J. Virol. Methods 2011, 171, 381–387. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J.; Milton J.; Weaver K. L.; Short S. A.; Stuart D. I.; Stammers D. K. Structural basis for the resilience of efavirenz (DMP-266) to drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Structure 2000, 8, 1089–1094. 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00513-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. J.; Short W. R. Rilpivirine, a novel non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor for the management of HIV-1 infection: a systematic review. Antiviral Ther. 2012, 17, 1495–1502. 10.3851/IMP2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Picado J.; Martinez M. A. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance mutations and fitness: a view from the clinic and ex vivo. Virus Res. 2008, 134, 104–123. 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.