Abstract

Objectives

This national study examines differences between racial/ethnic groups on awareness of physical activity and reduced cancer risk and explores correlates of awareness including trust, demographic, and health characteristics within racial/ethnic groups.

Methods

The 2007 Health Information and National Trends Survey provided data for this study. After exclusions, 6,809 adults were included in analyses. Awareness of physical activity in reduced cancer risk was the main outcome. Logistic regression models tested relationships.

Results

Non-Hispanic Blacks had a 0.71 (0.54,0.93) lower odds of being aware of physical activity in reduced cancer risk than non-Hispanic Whites. Current attempts to lose weight were associated with greater odds for awareness among Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics (p<0.01). Among Non-Hispanic Blacks trust in print media and audio/visual media was associated with greater odds of awareness (p< 0.01).

Conclusions

This study is the first national study to examine racial/ethnic disparities in awareness of physical activity and cancer risk. Comparisons between racial/ethnic groups found Black-White disparities in awareness. Variables associated with awareness within racial/ethnic groups identify potential subgroups to whom communication efforts to promote awareness may be targeted.

Introduction

Physical activity offers numerous health benefits, including reduced risk for several cancers and promotion of cancer survivorship.(1-3) The association between physical activity and cancer risk is strongest for breast and colorectal cancer, (4-7) two of the five most prevalent cancer sites in the US.(8) Evidence also supports a relationship between physical activity and endometrial cancer and continues to grow for other cancer sites.(5) Despite evidence for its health benefits,(7, 9) national levels of physical activity remain below public health recommendations, particularly for the non-Hispanic Black population, who experience lower levels of physical activity compared to non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics.(10-12) According to 2005 BRFSS, among women, non-Hispanic whites had the greatest prevalence of regular physical activity (49.6%), followed by Hispanics (40.5%), and non-Hispanic Blacks (36.1%). Among men, non-Hispanic whites had the greatest prevalence of regular physical activity (52.3%), followed by non-Hispanic Blacks (45.3%), and Hispanics (41.9%).(10)

Surveillance and promotion of public awareness of the relationship between physical activity and cancer risk offers an important strategy for population-level cancer control and communication.(13-15) First, identifying those who are aware or unaware of the relationship may help target current and future health communication and dissemination efforts to prevent cancer and promote healthy behavior.(14) Second, behavioral theories (e.g. protection motivation theory and transtheoretical model{Prochaska, 2008 #3;Prochaska, 1992 #377}) suggest individual’s beliefs and understanding of behavior’s ability to achieve a particular health outcome may be a predictor of whether the individual will engage in that behavior.(16-19) The association between awareness of health benefits and healthy behaviors has been documented for behaviors including alcohol(20) and fruit and vegetable consumption.(21, 22) Several studies found awareness of benefits of physical activity on reduced cancer risk can increase motivation and engagement in physical activity.(16, 23) Thus, identifying differences in population awareness of benefits of physical activity on reduced cancer risk by race/ethnicity could not only help target communication efforts, but may also identify means to promote physical activity and reduce health disparities.

Few nationally representative studies have examined racial/ethnic disparities in awareness of health behaviors and reduced cancer risk (e.g. tobacco use, diet, and physical activity).(24-26) These studies include examination of socioeconomic disparities in awareness of tobacco and sun exposure(25) on cancer risk, and two studies on racial/ethnic disparities:(24, 26) specifically on internet usage and knowledge gaps in physical activity(24) and on tobacco awareness and cancer risk.(26) Other national studies examined physical activity awareness in colon cancer risk, and awareness of multiple lifestyle behaviors on cancer risk, but neither examined potential differences in awareness by race/ethnicity.(13, 27) Thus, little is known about racial/ethnic disparities in awareness of the benefits of cancer preventive behaviors—particularly physical activity—in reduced cancer risk.

Communication of health information to promote awareness in cancer prevention involves consideration for several factors including trust. Trust in sources of health information influences reception of messages from source to receiver and is associated with perceived credibility and accuracy.(28) Greater trust in sources of information could influence enhanced receptivity to a particular health message. Consequently, if one trusts a particular health information source disseminating physical activity and cancer risk information, trust in this source may be associated with enhanced awareness of physical activity and cancer risk. However literature has not explored this potential relationship. While research studies have reported racial-ethnic differences in trusted of sources of health information, (29-32) to our knowledge, no national study has expanded upon findings to explore trusted sources of information and their potential association with awareness of preventative behaviors and cancer risk by racial/ethnic group.

This paper describes an exploratory study examining racial/ethnic differences in awareness of the effects of physical activity on cancer risk in a nationally representative survey, the 2007 National Cancer Institute Health Information National Trends Survey. First, differences in awareness of the effects of physical activity on cancer risk were examined across racial/ethnic groups. The authors’ hypothesize in parallel to observed disparities in physical activity, racial/ethnic minorities will be less aware of the benefits of physical activity on reduced cancer risk compared to Non-Hispanic Whites. Second, reported levels of physical activity are assessed for potential moderating effects on the relationship between race/ethnicity and awareness. Third, within-group demographic and trusted sources of information variables associated with awareness are explored because other studies have found within-group racial/ethnic differences on similar variables associated with awareness for other health outcomes (33).

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This study is a secondary data analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). The HINTS, a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey of the US civilian, non-institutionalized adult population, collected data using dual modes: a pencil and paper survey through mail and a telephone survey using random digit dialing (RDD). Data were collected between January-April 2008. A total of 7,674 individuals responded to the mail and telephone surveys, with 3,593 individuals responding to the mail survey and 4,081 responding to the RDD survey. A detailed description of HINTS instrument development and sampling design are published on the NCI HINTS web site.(34) The weighted response rate, calculated using standard methodology from the American Association for Public Opinion Research,(35) was 31% for the mail mode (this rate was computed by multiplying household 40.0% and within household rates 77.4%) and 24% for the RDD mode (this was computed by multiplying the household response rate 42.4% by the within household response rates 57.2%).

HINTS oversampled African Americans and Hispanics to ensure adequate representation of these two major US minority groups. Samples from the two modes were combined in this analysis. The primary inclusion criteria were those reporting their race/ethnicity, given research study objectives. We excluded those with missing data for education (0.1%), age (0.7%), physical activity (0.3%) and for “don’t know,” “missing,” or “increases chance of cancer” responses on our dependent variable (3.8%). Thus, a total of 6,469 adults were included in the study.

Measures

Dependent variable

Awareness of physical activity and cancer risk (awareness) was measured using 1 item: “As far as you know, does physical activity or exercise increase the chances of getting some types of cancer, decreases the chance of getting cancer, or does not make much difference?” Responses were converted into a dichotomous variable: “physical activity or exercise decreases the chance of getting some type of cancer” or “makes no difference.” Those reporting “increases chances of cancer” were excluded because conceptually we were interested in examining awareness of cancer prevention information versus assessing a “correct” or “incorrect” answer to the question. Furthermore, the total number of responses was deemed too small to create a third outcome category (0.6%).

Sociodemographic variables

Age was reported in the following five categories: 18-34(reference), 35-49, 50-64, 65-74, and 75 and older. Race/ethnicity was defined following the US Office of Management and Budget definitions. Racial/ethnic groups included in the analysis were: Non-Hispanic White (reference), Hispanic, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic Asian, and Non-Hispanic Other (American Indian, Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander) or Mixed race. Education was categorized as less than high school, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate (reference). Income was not included in the analysis to avoid multicollinearity effects and because of concerns for missing data.

Control variable

This analysis combines data from the mail and the RDD survey modes. To control for any potential mode effects, mode was coded as a dichotomous variable and entered as a covariate in the regression analysis.

Health variables

Health variables included physical activity level, prior cancer diagnosis, and current attempts to lose weight. These variables were selected because they may predispose individuals to seek health information regarding physical activity and cancer. The 2008 Department of Health and Human Services physical activity guidelines for total weekly amounts of aerobic physical activity defined physical activity level: inactive (no activity), low (<150 minutes/week), medium (150-300 minutes/week), high (>300 minutes/week).(9) Current attempts to lose weight were measured with 1 item, “Have you tried to lose any weight in the past 12 months?” This measure was coded as a dichotomous variable where 1-Yes and 0-No. Prior cancer diagnosis was measured with 1 item, “Have you ever been diagnosed as having cancer?” This measure was coded as a dichotomous variable 1-Yes and 0-No.

Trusted sources of health information variables

A series of nine questions measured trust in sources of health information. The questions include: “In general, how much would you trust information about health or medical topics from…a doctor or other health care professional, family or friends, newspapers or magazines, radio, internet, television, government health agencies, charitable organizations, and religious organizations and leaders.” Responses were on a 4-point Likert scale, which were reverse coded: 4-a lot, 3-some, 2-a little, 1-or not at all. We decided a priori to collapse trust variables into the following categories: health professionals (measured with one item, trust in a doctor or other health care professional), social networks (mean of two items: trust in family and friends and in religious organizations and leaders (α=0.758)), print media (mean of two items: trust in newspapers and magazines and the internet (α=0.775)), audio/visual media (mean of trust in radio and television (α=0.819)), and organizations (mean of trust in charities and government organizations (α=0.846)). Missing data for trust variables were excluded from analysis using listwise deletion (0.5-4.9%).

Data Analysis

Logistic regression models estimated odds of reporting awareness of physical activity and cancer risk. For the first study objective, between group differences by racial/ethnic group on the odds of reporting awareness were examined controlling for physical activity level and demographic characteristics in the full sample. For the second objective, the interaction of race/ethnicity and physical activity level was added to the regression model. For the third objective, stratified analyses by racial/ethnic group explored within group correlates of awareness. Each trust measure was entered into the logistic regression model separately with other covariates: demographic and health characteristics.

The models were also tested controlling for BMI and health insurance status. However, these models are not reported in the paper because they did not significantly change results. SUDAAN 9.0 was used for analysis incorporating jackknife replicate weights to obtain population level point estimates and parameters and calculate appropriate standard errors. Given the multiple comparisons conducted in analysis and subsequent concerns for inflated Type I error, we conducted modified Bonferroni tests of significance, which adjusts for multiple comparisons. This procedure examines pair-wise comparisons from the largest to smallest p-values and calculates an alpha level for significance testing based on the following formula: 0.05/(number of total pair-wise comparisons-rank order of significance +1).(36)

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the entire sample and by racial/ethnic group. Hispanics were younger with 50.2% between 18-34 years old compared to other racial/ethnic groups (χ2 (16)= 1316.1, p<0.01). Hispanics had the lowest levels of education with 35.1% with less than a high school education, while Non-Hispanic Whites, Non-Hispanic Asians, and mixed race subgroups reported greater than 50% with some college or college graduate degree (χ2 (12)= 1298.8, p<0.01).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for total sample and by race/ethnicity (weighted percents)

| % Total (n=6,809) | % NH-White (n=5,207) | % NH- Black (n=638) | % Hispanic (n=569) | % NH-Asian (n=188) | % Mixed Race/Other (n=207) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| 18-34 | 30.8 | 26.5 | 31.6 | 50.2 | 36.3 | 37.4 |

| 35-49 | 29.4 | 28.6 | 31.1 | 28.6 | 39.4 | 28.8 |

| 50-64 | 23.6 | 25.8 | 23.5 | 13.6 | 18.6 | 22.8 |

| 65-74 | 8.3 | 9.5 | 7.4 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 5.7 |

| 75+ | 8.0 | 9.7 | 6.3 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 5.3 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 48.1 | 48.1 | 40.3 | 54.0 | 56.7 | 41.9 |

| Female | 51.8 | 51.9 | 59.7 | 46.0 | 43.3 | 58.1 |

| Education | ||||||

| < high school | 14.0 | 9.5 | 19.6 | 35.1 | 8.2 | 14.7 |

| High school | 26.3 | 25.7 | 28.5 | 30.6 | 17.2 | 28.7 |

| Some college | 34.9 | 37.1 | 34.9 | 24.6 | 27.8 | 40.5 |

| College graduate | 24.8 | 27.8 | 17.0 | 9.7 | 46.8 | 16.2 |

| Mode | ||||||

| 56.0 | 56.2 | 64.4 | 45.2 | 64.0 | 51.1 | |

| Phone | 44.0 | 43.8 | 35.6 | 54.8 | 36.0 | 48.9 |

| Activity level | ||||||

| Inactive | 34.4 | 31.2 | 42.9 | 42.8 | 39.7 | 31.5 |

| <150/week | 28.2 | 29.3 | 23.8 | 23.0 | 33.7 | 34.6 |

| 150-300 week | 20.4 | 21.8 | 15.3 | 17.4 | 20.2 | 21.1 |

| >= 300/week | 17.1 | 17.7 | 18.0 | 16.8 | 6.4 | 12.9 |

| Trying to lose weight | 53.9 | 55.5 | 52.0 | 52.6 | 36.5 | 55.2 |

| Cancer survivor | 7.2 | 8.8 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 7.3 |

| Awareness | ||||||

| PA makes no difference | 38.2 | 36.2 | 49.6 | 38.1 | 38.1 | 45.8 |

| PA reduces risk | 61.8 | 63.8 | 50.4 | 61.9 | 61.9 | 54.2 |

Slightly more of the sample responded to the mail survey mode (56.0%), although there were no significant differences in mode response by racial/ethnic group (χ2 (4)= 1.8, p=0.78). The majority of respondents were physically inactive (34.4%) and a greater proportion of Non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, and Non-Hispanic Asians were inactive compared to Non-Hispanic Whites (χ2 (12)= 85.2, p<0.01). Over half of the sample reported current attempts to lose weight (53.9%). More Non-Hispanic Whites reported they had a prior cancer diagnosis (χ2 (4)= 250.8, p<0.01) compared to the other racial/ethnic groups. Although the majority of respondents reported physical activity decreases cancer risk (61.8%), over one-third of respondents reported physical activity makes no difference (38.2%).

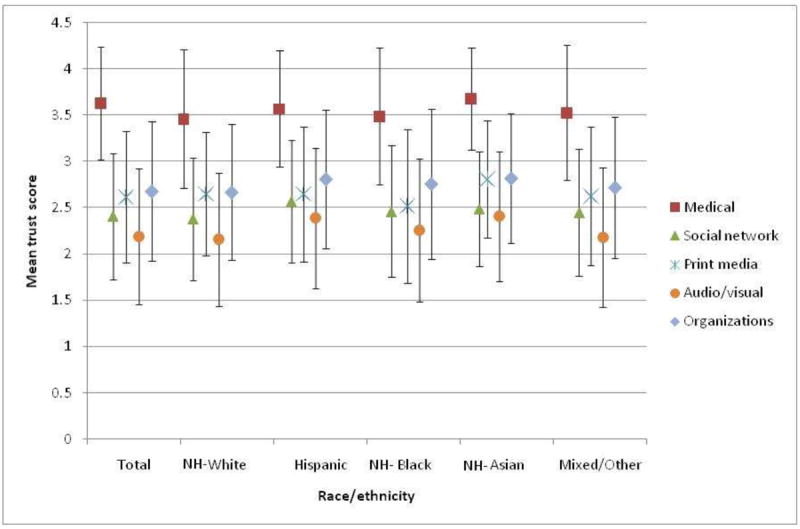

As shown in Figure 1, medical professionals was the most trusted source of information. Non-Hispanic Blacks reported more trust in social networks than Non-Hispanic Whites (p<0.05). Hispanics, Non-Hispanic Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Asians reported greater trust in audio/visual media compared to Non-Hispanic Whites (p<0.05). Non-Hispanic Asians were more trusting of print media than Non-Hispanic Whites (p<0.05). Non-Hispanic Blacks reported more trust in organizations than Non-Hispanics Whites (p<0.05).

Figure 1. Mean trust scorea and standard errors for sources of information by race/ethnicity.

a Scores are based on the following: 4- trust a lot, 3-trust some, 2-trust a little, 1- trust not at all

Between group disparities by race/ethnicity

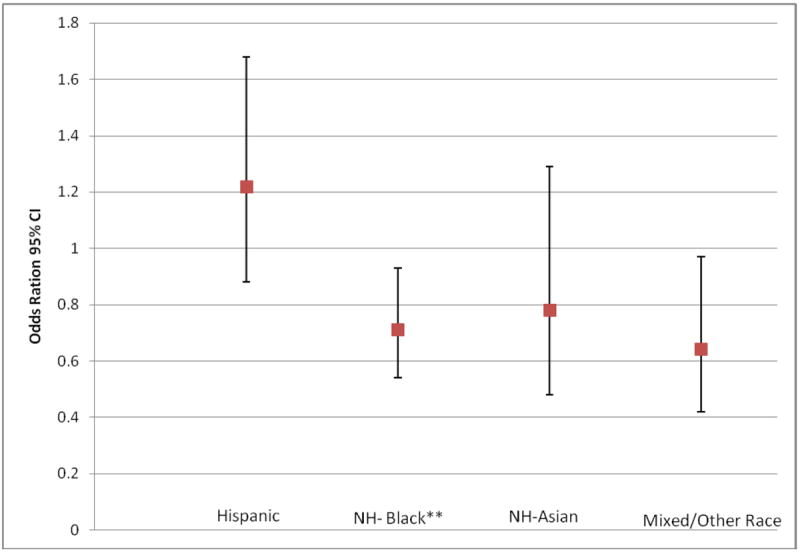

Figure 2 reports odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals on the odds of awareness for Hispanics, Non-Hispanic Blacks, Non-Hispanic Asians, and Mixed/Other race groups compared to Non-Hispanic Whites (reference), after statistically adjusting for demographic and health characteristics. Results indicate Non-Hispanic Blacks had a 0.71 (0.54,0.93) decreased odds in reporting awareness compared to Non-Hispanic Whites. Results also indicated those reporting less than a high school education had a 0.40 (0.30,0.55) lower odds of awareness compared to those with a college degree (results not reported in the figure). The interaction effect between race/ethnicity and physical activity was not significant, and thus the results are not reported here.

Figure 2. Between group disparities in odds of awareness of physical activity and cancer riska.

a Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are displayed for race/ethnicity when awareness was regressed on race/ethnicity (ref: White), age (ref:75+), gender (ref:female), education (ref: college), mode (ref:RDD), activity level (ref:inactive), trying to lose weight (ref:no), and cancersurvivor (ref:no); * p<0.05, **p<0.01

Within group covariates of awareness by racial/ethnic group

In stratified analyses by racial/ethnic group (Table 2 models 1-5A), we observed variability in significant covariates by race/ethnicity. Among Whites (Model 1A), those who were more inactive, female, and had a college education had greater odds of reporting awareness. Among Hispanics, those reporting attempts to lose weight had 2.22 (1.26,3.92) greater odds of reporting awareness compared to those who did not report attempts to lose weight (model 2A). Hispanics responding to the RDD survey had a greater odds of awareness compared to those responding to the mail mode. Non-Hispanic Blacks with a high school education had a lower odds of reporting awareness compared to those who had a college degree (model 3A). Non-Hispanic Blacks reporting current attempts to lose weight had a 1.67 (1.01,2.76) greater odds of awareness compared to those not attempting to lose weight (model 3A). None of the covariates were significant in stratified models for non-Hispanic Asian and Mixed race/other groups.

Table 2.

Stratified logistic regression models by race/ethnicity

| Model 1: NH- White OR 95% CI | Model 2: Hispanic OR 95% CI | Model 3: NH-Black OR 95% CI | Model 4: Asian OR 95% CI | Model 5: Mixed/Other OR 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Models regressing awareness on demographic and health characteristics | |||||

| Demographic | |||||

| Age (ref: 18-34) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 35-49 | 0.97 (0.71,1.31) | 1.05 (0.55,2.00) | 0.89 (0.41, 1.93) | 2.11 (0.53, 8.40) | 0.53 (0.18, 1.62) |

| 50-64 | 1.02 (0.78,1.34) | 0.88 (0.44,1.74) | 0.93 (0.47, 1.85) | 1.71 (0.48, 6.17) | 0.67 (0.15,3.07) |

| 65-74 | 0.80 (0.57, 1.12) | 1.18 (0.44,3.16) | 0.88 (0.35, 2.17) | 1.29 (0.17, 9.92) | 0.79 (0.17, 3.68) |

| 75+ | 0.62 (0.44, 0.86)** | 0.66 (0.15, 2.84) | 1.88 (0.66, 5.32) | 0.63 (0.01,37.36) | 0.44 (0.04, 4.47) |

| Gender (ref: female) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.0 |

| Male | 0.82(0.69,0.97)* | 1.45(0.86,2.45) | 1.16(0.65,2.09) | 1.11 (0.36,3.41) | 1.03 (0.34, 3.15) |

| Education (ref: college | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.0 |

| < high school | 0.28(0.19,0.40)** | 0.68(0.29,1.61) | 0.39(0.17,0.90) | 1.75 (0.27,11.38) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.35) § |

| High school | 0.45(0.36,0.56) ** | 0.47(0.22,1.03) § | 0.40(0.21,0.76) § | 0.96 (0.15,6.18) | 0.54 (0.12, 2.42) |

| Some college | 0.69(0.56,0.85) ** | 0.66(0.30,1.46) | 0.85(0.44,1.62) | 0.35 (0.11, 1.07) | 0.83 (0.22, 3.14) |

| Mode (ref: RDD) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.0 |

| 1.01(0.84,1.20) | 0.47(0.25,0.85)* | 0.61(0.35,1.09) | 1.84 (0.65, 5.27) | 0.57 (0.19, 1.65) | |

| Health characteristics | |||||

| Activity (ref: inactive) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.0 |

| <150/week | 1.36(1.09,1.69)** | 1.96 (0.84,4.10) | 1.40(0.80,2.48) | 2.10 (0.71, 6.18) | 2.94 (0.89, 9.75) |

| 150-300 week | 1.73(1.36,2.20)** | 1.53 90.67,3.50) | 1.71(0.81,3.61) | 1.19 (0.23, 6.24) | 1.12 (0.26, 4.77) |

| >= 300/week | 1.40(1.08,1.80)** | 0.91 (0.39,2.15) | 0.91(0.36,2.28) | 1.84 (0.10, 35.14) | 2.79 (0.46, 17.06) |

| Lose weight (ref:no) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 1.08(0.89,1.30) | 2.22 (1.26,3.92)** | 1.67(1.01,2.76)* | 2.09 (0.59, 7.32) | 1.11 (0.37,3.32) |

| Cancer survivor (ref:no) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 1.08(0.87,1.34) | 1.04(0.31,3.54) | 0.74(0.28,1.93) | 4.66 (0.30, 73.30) | 0.71 (0.19,2.65) |

| B. Models regressing awareness on demographic and health characteristics (not shown) and trusted sources of information | |||||

| Trusted Sources of Informationa,b | |||||

| Medical (physician) | 1.12(0.93,1.35) | 1.23(0.81,1.88) | 0.95(0.61,1.47) | 0.71 (0.31,1.64) | 1.82 (0.66,5.03) |

| Social network | 1.18(1.04,1.35)** | 1.02(0.65,1.60) | 1.29(0.86,1.96) | 1.02 (0.43,2.41) | 1.89 (0.76,4.68) |

| Print media | 1.39(1.18,1.62)** | 1.19(0.74,1.90) | 2.13(1.33,3.41)** | 1.86 (0.80,4.32) | 1.36 (0.58,3.15) |

| Audio/visual | 1.34(1.17,1.53)** | 1.36(0.87,2.11) | 2.02(1.35,3.04)** | 1.95 (0.90,4.21) | 1.41 (0.61,3.28) |

| Organizations | 1.34(1.17,1.53)** | 1.23(0.81,1.88) | 0.95(0.61,1.47) | 1.14 (0.44,2.99) | 2.75 (1.27,5.96) |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

Significant following modified Bonferroni test of significance with adjusted p-value calculated as 0.05/(number of total comparisons-rank order +1);

Scores are based on the following: 4- trust a lot, 3-trust some, 2-trust a little, 1- trust not at all;

each trust variable was entered into the model separately, but are presented here together to facilitate within group comparisons

Trusted sources of information and awareness

Among the non-Hispanic White population (Table 2, model 1B), trust in social network, print media, audio/visual and organizational information sources were associated with the greater odds of awareness (p< 0.01). For non-Hispanic Blacks (Table 2, model 3B), trust in print media and audio/visual media were associated with greater odds of awareness (p< 0.01). None of the trust variables were significant in the odds of awareness for the Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and Mixed race/other racial/ethnic groups (Table 2, models 2B,4-5B).

Discussion

This study is the first national study to examine racial/ethnic disparities in awareness of physical activity and cancer risk. Comparisons between racial/ethnic groups found disparities in awareness. After controlling for demographic and health characteristics, non-Hispanic Blacks had a 0.71 (0.54,0.93) lower odds of being aware of physical activity and reduced cancer risk than non-Hispanic Whites. Among Non-Hispanic Blacks, those with less than a high school education also had a lower odds of being aware of physical activity and cancer risk compared to those with a college degree.

While activity level did not moderate the observed between group disparities in awareness, a relationship was observed between activity level and awareness in stratified analysis among Non-Hispanic Whites. This finding parallels the Hawkins, et al (2007) study, which found adults who were physically active were more likely to be aware of physical activity and reduced cancer risk,(13) and other behavioral studies reporting an association between awareness and behavior.(37) However, this relationship between awareness and behavior was not observed within the other racial/ethnic groups. Findings for education across racial/ethnic groups were similar to prior studies reporting individuals with lower levels of education and income were not aware of the benefits of lifestyle behaviors in reduced cancer risk (13, 37-38) and may be less likely to recall health messages. (39) Lower reported awareness among those with less education could indicate several issues including limited access to information (14, 39) and lower health literacy levels.(40) While those issues are outside of the scope of this study, findings do highlight the need to target communication efforts towards those with lower levels of education, who are less likely to be aware of physical activity benefits on reduced cancer risk.

In stratified analyses, significant covariates differed within racial/ethnic groups and highlight potential subpopulation targets for health communication efforts to increase awareness. Current attempts to lose weight were associated with awareness for Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics, but not for Non-Hispanic Whites. Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics attempting to lose weight may have had more exposure to or sought information about physical activity, thus enhancing their awareness of health benefits compared to those not attempting to lose weight. Among Hispanics, survey mode was a significant covariate of awareness. Language accessibility may have biased the responses from the mail mode for respondents with limited English proficiency as the mail mode survey was not available in Spanish. Replicating this study to include a Spanish version of the survey for the mail mode could result in different findings.

Data from the 2002-2003 HINTS found the most trusted source of health information was physicians.(41) Results from this study indicate trust in health professionals remains the most trusted source of information overall and within racial/ethnic groups. Yet, trust in health professionals was not associated with awareness for any of the racial/ethnic groups. Similar to prior research indicating racial/ethnic disparities in access and preferences for particular information sources,(42) the relationship between trusted information sources on awareness varied across racial/ethnic groups. A greater diversity of trusted sources of information were associated with awareness among non-Hispanic Whites (e.g., social networks, print media, audio/visual and organizations), with fewer sources among other racial/ethnic groups. This finding may suggest greater access and acceptability of the sources of information in this study among Non-Hispanic Whites. Among Non-Hispanic Blacks, print media and audio/visual sources of information were associated with awareness. A two-year national study found Black newspapers printed more cancer information in comparison to mainstream media.(43) Thus, it is possible Non-Hispanic Blacks in our study who reported trust in print media could have had greater access to information on physical activity and cancer risk. Among Hispanics, Non-Hispanic Asians, and Mixed/Other race groups, trust in any of the sources of information was not associated with awareness. For these groups, despite similarities in absolute levels of trust for sources of information when compared with other racial/ethnic groups, language or culture-related accessibility of media may have been a barrier to comprehension and acceptability of the information.(44, 45) Specific cultural beliefs about cancer and preventive health behaviors as well as preferences for particular information sources may be important to consider in these populations when measuring trust and the role of trust in awareness of exercise and cancer risk.(41, 45, 46)

There are several limitations to this study. First, these data were cross-sectional and determining causality was not possible. Second, the mail survey was only available in the English language. Third, HINTS did not oversample Non-Hispanic Asians, American Indians, Alaskan Natives and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders. Consequently, stratified racial/ethnic analyses for these subgroups were limited. More research among these subgroups is necessary to further explore awareness of physical activity and reduced cancer risk.

There were several strengths to our study. First, this is a nationally representative study oversampling relatively large US minority populations, Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics. Second, the HINTS survey used a dual-frame design with the sample including those who possess landline telephones through the RDD sample in addition to cell-phone only respondents through the mail survey. By including both modes in the sample, analyses were able to potentially control for social desirability biases associated with mode of data collection.

This exploratory study identified racial/ethnic disparities in awareness of physical activity and cancer risk. Findings highlight a need for enhanced physical activity communication efforts among the non-Hispanic Black population, particularly in light of the relatively low levels of activity reported in this population.(11) This study explored factors associated with awareness within racial/ethnic groups and findings support the potential efficacy of tailored and targeted health communication messages as an important strategy to promote awareness of the linkages between physical activity and cancer risk. For instance, results suggest communication efforts specifically target Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks not attempting to lose weight, as well as inactive non-Hispanic Whites, and those of lower education. While there is a proliferation of new media sources with advancement in technology which can be used to disseminate cancer information,(14) communication efforts should not ignore traditional print and other audio/visual media channels, particularly among non-Hispanic Blacks. In addition, more research with greater sample sizes among non-Hispanic Asians and Mixed race or other racial ethnic groups such as Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders and American Indians on awareness of physical activity and cancer risk would contribute to greater understanding of cultural tailoring and targeting of communication messages among these populations.(46-48) Furthermore, while this study explored demographic, health and trust variables and its association with awareness, there may be other noteworthy variables that may have a relationship with awareness (e.g. cancer fatalism, cultural beliefs about cancer, acculturation) which could be explored further in future studies.

References

- 1.Friedenreich C, Norat T, Steindorf K, Boutron-Ruault MC, Pischon T, Mazuir M, et al. Physical activity and risk of colon and rectal cancers: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15(12):2398–2407. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lahmann PH, Friedenreich C, Schuit AJ, Salvini S, Allen NE, Key TJ, et al. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: The European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2007;16(1):36–42. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curry SJ, Byers T, Hewitt M. Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers CJ, Colbert LH, Greiner JW, Perkins SN, Hursting SD. Physical activity and cancer prevention : pathways and targets for intervention. Sports Med. 2008;38(4):271–96. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McTiernan A. Mechanisms linking physical activity with cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(3):205–11. doi: 10.1038/nrc2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan SY, DesMeules M. Energy intake, physical activity, energy balance, and cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:191–215. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Cancer Research Fund AICR. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(1):10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DHHS. Services UDoHaH. Rockville, MD: 2008. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC. Prevalence of Regular Physical Activity Among Adults—United States, 2001 and 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1209–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–8. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins MS, Storti KL, Richardson CR, King WC, Strath SJ, Holleman RG, et al. Objectively measured physical activity of U.S. adults by sex, age, and racial/ethnic groups: Cross-sectional Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6(1):31. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkins NA, Berkowitz Z, Peipins LA. What Does the Public Know About Preventing Cancer? Results From the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Health Educ Behav. 2007 doi: 10.1177/1090198106296770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viswanath K. Science and society: the communications revolution and cancer control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(10):828–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreps GL. Strategic use of communication to market cancer prevention and control to vulnerable populations. Health Marketing Quarterly. 2008;25(1/2):204–216. doi: 10.1080/07359680802126327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Courneya KS, Hellsten L-A. Cancer prevention as a source of exercise motivation: an experimental test using protection motivation theory. Psychol Health Med. 2001;6:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood ME. Theoretical framework to study exercise motivation for breast cancer risk reduction. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(1):89–95. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azjen I. Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker MH. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monograph. 1974;2:324–473. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaskutas LA, Graves K. Relationship between cumulative exposure to health messages and awareness and behavior-related drinking during pregnancy. Am J Health Promot. 1994;9(2):115–24. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Duyn MA, Kristal AR, D K, Campbell MK, Subar AF, Stables G, Nebeling L, Glanz K. Association of awareness, intrapersonal and interpersonal factors, and stage of dietary change with fruit and vegetable consumption: a national survey. Am J Health Promot. 2001;16(2):69–78. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-16.2.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf RL, Lepore SJ, Vandergrift JL, Basch CE, Yaroch AL. Tailored telephone education to promote awareness and adoption of fruit and vegetable recommendations among urban and mostly immigrant black men: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2009;48(1):32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Midtgaard J, Baadsgaard MT, Moller T, Rasmussen B, Quist M, Andersen C, et al. Self-reported physical activity behaviour; exercise motivation and information among Danish adult cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13(2):116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shim M. Connecting internet use with gaps in cancer knowledge. Health Commun. 2009 doi: 10.1080/10410230802342143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viswanath K, Breen N, Meissner H, Moser RP, Hesse B, Steele WR, et al. Cancer knowledge and disparities in the information age. J Health Commun. 2006;11(Suppl 1):1–17. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finney Rutten LJ, Augustson EM, Moser RP, Beckjord EB, Hesse B. Smoking knowledge and behavior in the United States: sociodemographic, smoking status, and geographic patterns. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(10):1559–70. doi: 10.1080/14622200802325873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coups EJ, Hay J, Ford JS. Awareness of the role of physical activity in colon cancer prevention. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;72(2):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiede M. Information and access to health care: is there a role for trust? Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1452–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adegbembo AO, Tomar SL, Logan HL. Perception of racism explains the difference between Blacks’ and Whites’ level of healthcare trust. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):792–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wasserman J, Flannery MA, Clair JM. Raising the ivory tower: the production of knowledge and distrust of medicine among African Americans. J Med Ethics. 2007;33(3):177–80. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.016329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halbert CH, Armstrong K, Gandy OH, Jr, Shaker L. Racial differences in trust in health care providers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8):896–901. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whetten K, Leserman J, Whetten R, Ostermann J, Thielman N, Swartz M, et al. Exploring lack of trust in care providers and the government as a barrier to health service use. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(4):716–721. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lutfiyya MN, Cumba MT, McCullough JE, Barlow EL, Lipsky MS. Disparities in adult African American women’s knowledge of heart attack and stroke symptomatology: an analysis of 2003-2005 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey data. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(5):805–13. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NCI. Health Information National Trends Survey: How Americans find and use cancer information. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 35.AAPOR. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. Research AAfPO [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redeker C, Wardle J, Wilder D, Hiom S, Miles A. The launch of Cancer Research UK’s ‘Reduce the Risk’ campaign: baseline measurements of public awareness of cancer risk factors in 2004. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(5):827–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winterich JA, Grzywacz JG, Quandt SA, Clark PE, Miller DP, Acuna J, et al. Men’s knowledge and beliefs about prostate cancer: education, race, and screening status. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):199–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benjamin-Garner R, Oakes JM, Meischke H, Meshack A, Stone EJ, Zapka J, et al. Sociodemographic differences in exposure to health information. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(1):124–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kickbusch IS. Health literacy: addressing the health and education divide. Health Promot Int. 2001;16(3):289–97. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Croyle RT, Arora NK, Rimer BK, et al. Trust and sources of health information - The impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: Findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(22):2618–2624. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Malley AS, Kerner JF, Johnson L. Are we getting the message out to all? Health information sources and ethnicity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;17(3):198–202. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caburnay CA, Kreuter MW, Cameron G, Luke DA, Cohen EL, McDaniels L, et al. Black newspapers as a tool for cancer education in African American communities. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(4):488–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neuhauser L, Kreps GL. Online cancer communication: meeting the literacy, cultural and linguistic needs of diverse audiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(3):365–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oetzel J, De Vargas F, Ginossar T, Sanchez C. Hispanic women’s preferences for breast health information: subjective cultural influences on source, message, and channel. Health Commun. 2007;21(3):223–33. doi: 10.1080/10410230701307550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Resnicow K, Braithwaite R, DiIorio C, Glanz K. Applying Theory to Culturally Diverse and Unique Populations. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis F, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education. Jossey-Bass, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Resnicow K, Davis RE, Zhang G, Konkel J, Strecher VJ, Shaikh AR, et al. Tailoring a fruit and vegetable intervention on novel motivational constructs: results of a randomized study. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):159–69. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz RD, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(2):133–46. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]