Abstract

Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1) is a multifunctional protein expressed by cells from a large variety of tissues. It is involved in many physiological and pathological processes, including bone metabolism, inflammation progress, tumor metastasis, injury repair, and hyperoxia-induced injury. Native SPP1 from multiple species have been isolated from the milk and urine, and recombinant SPP1 with different tags have been expressed and purified from bacteria. In our study, DNA fragments corresponding to mouse SPP1 without signal peptide were built into the pET28a(+) vector, and non-tagged recombinant mouse SPP1 (rmSPP1) was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). rmSPP1 was purified using a novel tri-step procedure, and the product features high purity and low endotoxin level. rmSPP1 can effectively increase hepatocellular carcinoma cell (HCC) proliferation in vitro, demonstrating its biological activity.

Keywords: recombinant SPP1, biological activity, purity, HCC, cell proliferation

Introduction

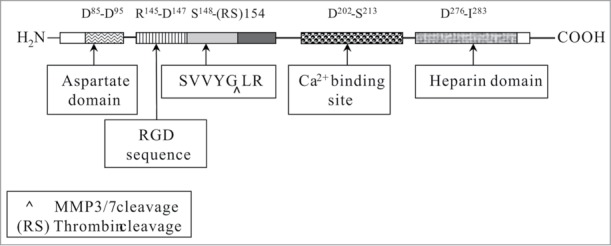

Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1) is a phosphorylated acidic glycoprotein, and human SPP1 is also named osteopontin (OPN).1,2 It was first identified as a major sialoprotein in bone matrix, expressed by both osteoclast and osteoblast cells. It regulates bone remodeling by inhibiting hydroxyapatite formation. Current studies have shown that SPP1 is expressed in most tissues of the body, including brain, vascular tissues, kidney, dentin, cementum, salivary, gut, mammary, liver, uterus, bone, activated macrophages, and lymphocytes.3 Human SPP1 has 3 isoforms: OPNa, OPNb, and OPNc. OPNa is the longest variation consisting of 314 amino acids (aa). OPNa mRNA has 7 exons, among which exon5 is absent in OPNb and exon4 is absent in OPNc. Murine SPP1 consists of 294aa, which features 59% amino sequence identity to OPNa.4 SPP1 has several conserved domains across different species that perform crucial biological functions. These domains include an arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) sequence, a thrombin cleavage site, an aspartate domain, a calcium binding motif, and two heparin binding sites, etc. (Fig. 1).4,5 SPP1 can bind to integrin αvβ5/(β1, β3) and (α8, α9)β1 via the RGD sequence and regulate cell migration, adhesion, chemotaxis, and so on.1 SPP1 might be a ligand to CD44v receptors as well, and thus it could potentially promote tumor metastasis and cell proliferation.6,7

Figure 1.

Functional domains and motifs in mouse SPP1 (modified from refs. 4 and 5).

SPP1 undergoes a series of maturation processes before its secretion, including the excision of its signal peptides (17 aa in human and 16 aa in mouse) at the N-terminus, phosphorylation, and glycosylation. Natural SPP1 has been isolated from milk,8,9 urine,10 and cultured rat smooth muscle cells,11 while recombinant SPP1 with GST or 6 times His have also been expressed in E. coli, and after purification these versions of recombinant SPP1 have been wildly applied to studies on the biological functions of SPP1.12-14 However, these tagged recombinant proteins are unsuitable for investigations on the pharmaceutical potential of SPP1 in animal disease models, because the tags might bring uncertainty to the proteins as drug candidates, while the removal of these tags would greatly decrease the productivity and increase cost. Recently, we have reported a procedure for expression and purification of biologically active non-tagged recombinant mouse SPP1 from E. coli, according to the physical and chemical properties of SPP1.15 In this procedure, the Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) was used as the host strain for expression of recombinant mouse SPP1 (rmSPP1, L17-N294). The procedure of mSPP1 purification could be divided into 3 steps, including process of crude products (isoelectric precipitation and ammonium sulfate precipitation), anion exchange chromatography, and cation exchange chromatography (Fig. 2). rmSPP1 with high purity (97%), low endotoxin level, and affirmative biological activity was produced using this procedure.15

Figure 2.

Flow scheme for recombinant mouse SPP1 expression and purification.

Biological activity is very important to recombinant protein, especially for products from bacteria. Most eukaryotic proteins have several kinds of post-translation modification, including phosphorylation, glycosylation, acetylation, ubiquitinylation, and sumoylation modification. However, prokaryotic cells lack corresponding enzymes and could not exert some of such post-translational modifications, if not all. In spite of this general disadvantage, recombinant SPP1 from bacteria has been widely used in biological function studies through the past 20 years.16-18 It has been shown that phosphorylation or glycosylation conditions of recombinant SPP1 would not affect its bioactivities except for those related with cell adhesion regulation.2 Interestingly, recombinant SPP1 cleaved by MMP3 has higher bioactivity than full-length SPP1 in terms of regulating cell migration.12 Current studies have indicated that recombinant SPP1 could improve hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation through binding to CD44 receptor.19 Here, we also described a novel method to test the biological activity of rmSPP1 in vitro.

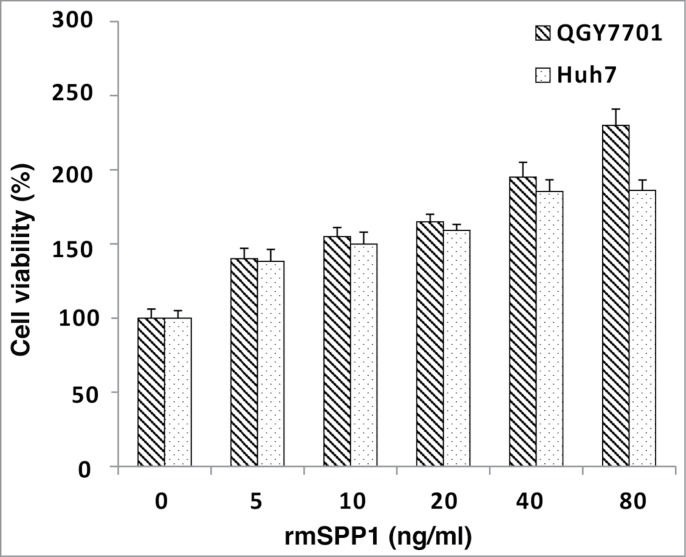

Hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines Huh7 and QGY7701 were employed to test the biological activity of rmSPP1. They were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS at 5% of CO2, 37 °C. For CCK-8 tests, cells were planted to 96-well plates with the density of 3000 cells per well and grown overnight. Cells were then treated with DMEM with 10% FBS containing different concentrations of rmSPP1 (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 ng/ml) for 4 days, and each group has triple duplicate wells. The experiments were repeated for three times. Cell viability was analyzed with CCK-8 cell counting kit and normalized by control group. Five ng/ml rmSPP1 in cell culture medium effectively increased cell growth rate, as compared with the control group in which PBS was added to cell culture medium instead of rmSPP1. According to previous studies, the highest cell growth ratio would be obtained at 40 ng/ml. (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

rmSPP1 improves Huh7 and QGY7701 cell proliferation. Cells were seeded to 96-well plates and maintained with DMEM (10%FBS) overnight. Then, the indicated concentration of rmSPP1 was added to medium every 24 h. PBS was used as control. Cell culture was continued for 4 days. Cell viability was analyzed with CCK-8 cell counting kit, and results were normalized by control group (n = 3, ± SD). Experiments were repeated 3 times.

Conclusion and Discussion

SPP1 in different species share common chemical characters; for example, isoelectric point (PI) of human SPP1 is 4.2, and that of mouse SPP1 is 4.3. Because the separation of proteins using ion exchange chromatography is realized according to certain chemical properties of proteins (e.g., PI), our procedure could be applied to purify human recombinant SPP1 with minor modification, and it could be easily modified for industrial production as well. Producing recombinant protein from bacteria expression system is more economically efficient, and contamination would be less likely to happen, compared with the mammalian cell expression system. Many research works have demonstrated that SPP1 could protect animals against hyperoxia-induced lung injury,20 cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury,21 alcohol or diethylnitrosamine-induced liver injury,22-24 and brain injury.25,26 So recombinant SPP1 would be a potential drug candidate in the future. rmSPP1 can be applied to rodent disease models for studying pharmaceutical mechanisms prior to preclinical studies. On the other side, under certain biological circumstances, SPP1 could promote tumor cell migration and proliferation in both paracrine and autocrine manners.7,27 Neutralization of endogenous SPP1 with anti-SPP1 antibody may be an effective method to inhibit tumor metastasis. Native recombinant SPP1 with high purity and biological activity is more appropriate than synthesized peptide in terms of raising polyclonal antibodies, and it is also more appropriate than tagged SPP1 in terms of raising monoclonal antibodies. In summary, we have provided a new strategy to express and purify native recombinant mouse SPP1 which has significant biological activity in vitro.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Yan Yu from Shanghai Jiao Tong University for reading and correcting the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural and Science Foundation of China (81302825 Y.S.Y.) and Key Laboratory of Urban Agriculture (South) Ministry of Agriculture (10UA002 Y.S.Y.).

References

- 1. Mazzali M, Kipari T, Ophascharoensuk V, Wesson JA, Johnson R, Hughes J. Osteopontin–a molecule for all seasons. QJM 2002; 95:3-13; PMID:11834767; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/qjmed/95.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rangaswami H, Bulbule A, Kundu GC. Osteopontin: role in cell signaling and cancer progression. Trends Cell Biol 2006; 16:79-87; PMID:16406521; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sodek J, Ganss B, McKee MD. Osteopontin. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2000; 11:279-303; PMID:11021631; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/10454411000110030101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yuan Y, Xie M, Qian Z, Zhang X, Yan D, Yu Y. Osteopontin: an important molecule in liver diseases. World Chin J Digestology 2011; 19:814. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Denhardt DT, Noda M, O’Regan AW, Pavlin D, Berman JS. Osteopontin as a means to cope with environmental insults: regulation of inflammation, tissue remodeling, and cell survival. J Clin Invest 2001; 107:1055-61; PMID:11342566; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI12980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gao C, Guo H, Downey L, Marroquin C, Wei J, Kuo PC. Osteopontin-dependent CD44v6 expression and cell adhesion in HepG2 cells. Carcinogenesis 2003; 24:1871-8; PMID:12949055; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/carcin/bgg139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee JL, Wang MJ, Sudhir PR, Chen GD, Chi CW, Chen JY. Osteopontin promotes integrin activation through outside-in and inside-out mechanisms: OPN-CD44V interaction enhances survival in gastrointestinal cancer cells. Cancer Res 2007; 67:2089-97; PMID:17332338; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sørensen S, Justesen SJ, Johnsen AH. Purification and characterization of osteopontin from human milk. Protein Expr Purif 2003; 30:238-45; PMID:12880773; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1046-5928(03)00102-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bayless KJ, Davis GE, Meininger GA. Isolation and biological properties of osteopontin from bovine milk. Protein Expr Purif 1997; 9:309-14; PMID:9126601; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/prep.1996.0699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christensen B, Petersen TE, Sørensen ES. Post-translational modification and proteolytic processing of urinary osteopontin. Biochem J 2008; 411:53-61; PMID:18072945; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/BJ20071021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liaw L, Almeida M, Hart CE, Schwartz SM, Giachelli CM. Osteopontin promotes vascular cell adhesion and spreading and is chemotactic for smooth muscle cells in vitro. Circ Res 1994; 74:214-24; PMID:8293561; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.RES.74.2.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gao YA, Agnihotri R, Vary CP, Liaw L. Expression and characterization of recombinant osteopontin peptides representing matrix metalloproteinase proteolytic fragments. Matrix Biol 2004; 23:457-66; PMID:15579312; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ashkar S, Teplow DB, Glimcher MJ, Saavedra RA. In vitro phosphorylation of mouse osteopontin expressed in E. coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1993; 191:126-33; PMID:8447818; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jang JH, Kim JH. Improved cellular response of osteoblast cells using recombinant human osteopontin protein produced by Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett 2005; 27:1767-70; PMID:16314968; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10529-005-3551-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yuan Y, Zhang X, Weng S, Guan W, Xiang D, Gao J, Li J, Han W, Yu Y. Expression and purification of bioactive high-purity recombinant mouse SPP1 in Escherichia coli. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2014; 173:421-32; PMID:24664233; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12010-014-0849-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agnihotri R, Crawford HC, Haro H, Matrisian LM, Havrda MC, Liaw L. Osteopontin, a novel substrate for matrix metalloproteinase-3 (stromelysin-1) and matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin). J Biol Chem 2001; 276:28261-7; PMID:11375993; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M103608200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saad FA, Salih E, Glimcher MJ. Identification of osteopontin phosphorylation sites involved in bone remodeling and inhibition of pathological calcification. J Cell Biochem 2008; 103:852-6; PMID:17615552; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcb.21453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mitchell EA, Chaffey BT, McCaskie AW, Lakey JH, Birch MA. Controlled spatial and conformational display of immobilised bone morphogenetic protein-2 and osteopontin signalling motifs regulates osteoblast adhesion and differentiation in vitro. BMC Biol 2010; 8:57; PMID:20459712; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1741-7007-8-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Phillips RJ, Helbig KJ, Van der Hoek KH, Seth D, Beard MR. Osteopontin increases hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth in a CD44 dependant manner. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18:3389-99; PMID:22807608; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3748/wjg.v18.i26.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang XF, Liu S, Zhou YJ, Zhu GF, Foda HD. Osteopontin protects against hyperoxia-induced lung injury by inhibiting nitric oxide synthases. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010; 123:929-35; PMID:20497690 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Y, Chen B, Shen D, Xue S. Osteopontin protects against cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury through late preconditioning. Heart Vessels 2009; 24:116-23; PMID:19337795; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00380-008-1094-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ge X, Leung TM, Arriazu E, Lu Y, Urtasun R, Christensen B, Fiel MI, Mochida S, Sørensen ES, Nieto N. Osteopontin binding to lipopolysaccharide lowers tumor necrosis factor-α and prevents early alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology 2014; 59:1600-16; PMID:24214181; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/hep.26931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ge X, Lu Y, Leung TM, Sørensen ES, Nieto N. Milk osteopontin, a nutritional approach to prevent alcohol-induced liver injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2013; 304:G929-39; PMID:23518682; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpgi.00014.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. He C, Fan X, Chen R, Liang B, Cao L, Guo Y, Zhao J. Osteopontin is involved in estrogen-mediated protection against diethylnitrosamine-induced liver injury in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2012; 50:2878-85; PMID:22609492; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.fct.2012.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suzuki H, Hasegawa Y, Kanamaru K, Zhang JH. Mechanisms of osteopontin-induced stabilization of blood-brain barrier disruption after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Stroke 2010; 41:1783-90; PMID:20616319; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.586537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Topkoru BC, Altay O, Duris K, Krafft PR, Yan J, Zhang JH. Nasal administration of recombinant osteopontin attenuates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2013; 44:3189-94; PMID:24008574; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Medico E, Gentile A, Lo Celso C, Williams TA, Gambarotta G, Trusolino L, Comoglio PM. Osteopontin is an autocrine mediator of hepatocyte growth factor-induced invasive growth. Cancer Res 2001; 61:5861-8; PMID:11479227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]