Abstract

Context:

Lichen planus is a psychosomatic disease. Higher frequency of psychiatric symptoms, poor quality of life, higher level of anxiety and neuroendocrine and immune dysregulations, all these factors, will enhance the exacerbation of the disease.

Aims:

The present study was to assess depression, anxiety and stress levels in patients with oral lichen planus.

Materials and Methods:

The psychometric evaluation using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)-42 questionnaire was carried out, by the same investigator on all members of group 1 (Oral Lichen Planus) and group 2 (Control). DASS-42 questionnaire consists of 42 symptoms divided into three subscales of 14 items: Depression scale, anxiety scale, and stress scale.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The Student t test was used to determine statistical difference for both the groups and to evaluate for significant relationships among variables.

Results:

Psychological assessment using DASS-42 reveals lichen planus patients showed higher frequency of psychiatric co morbidities like depression, anxiety and stress compared to control group.

Conclusions:

This study has provided evidence that the DASS-42 questionnaire is internally consistent and valid measures of depression, anxiety, and stress. Psychiatric evaluation can be considered for patients with oral lichen planus with routine treatment protocols are recommended. DASS-42 Questionnaire can also be used to determine the level of anxiety, stress and depression in diseases of the oral mucosa like recurrent apthous stomatitis, burning mouth syndrome and TMD disorders.

Keywords: Anxiety, DASS-42 questionnaire, depression, stress

What was known?

Factors such as stress and psychological problems, especially depression and anxiety, have been mentioned as etiologic factors in lichen planus. However, not many studies have been done for the evaluation of the relationship between oral lichen planus and psychiatric disorders.

Introduction

Psycho dermatology is an interesting area for interface between psychiatry and dermatology, as there is a bidirectional interaction between the between skin and mind. The ectoderm is the embryologic origin for nervous and most skin tissue. Skin plays several important functions both physiological and psychological. Psychologically, skin is an erogenous zone and channel for emotional discharge so that troubled skin could be a manifestation of unexpressed anger or an inner conflict due to external stress.[1] Lichen planus (LP) may represent the manifestation of a mucosal reaction to a variety of etiological factors. The cause is unknown, but it is classified as an autoimmune disorder which may be precipitated or exacerbated by psychosocial stressors.[1] LP is a relatively common disorder of the stratified squamous epithelia that affects the skin, scalp, nails, and mucosa.[2]

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) is a 42-item self-report measure of anxiety, depression and stress developed by Lovibond and Lovibond (1995).[3] It requires no special skills to administer. Each of the three subscales of DASS is intercorrelated with one another.

DASS-Depression: Characterized by low positive effect, loss of self-esteem and incentive, dysphonic mood (e.g. sadness or worthlessness) and a sense of hopelessness. DASS-Anxiety: Characterized by autonomic arousal and fearfulness (physiological hyper arousal) panic attacks, and fear (e.g. trembling or faintness). Depression and anxiety have a non-specific factor of general distress in common. DASS-Stress: Characterized by persistent tension, irritability, and a low threshold for becoming upset or frustrated (negative affect) and a tendency to overreact to stressful events.[4]

The purpose of this study was to assess depression, anxiety and stress levels in patients with oral lichen planus (OLP).

Materials and Methods

Our study was carried out on 25 patients with Oral Lichen Planus (group 1). All OLP cases are clinically and histological proven. The control group was composed of 25 subjects (group 2) who reported for routine dental treatment. Both the groups matched for age and sex. Patients who were willing to participate and educated enough to read and understand were included in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with OLP exhibited the characteristic clinical features of the disease, with histopathologic confirmation (basal layer hydropic degeneration and a profuse infiltration of lymphoid cells within the limits of the basal zone), and were not taking psychoactive drugs; (2) control subjects with no oral mucosal lesions and were not known to have undergone psychosomatic alterations or to be receiving psychoactive medication.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients exhibiting dysplasia in histopathological evaluation. (2) Patients with lichenoid reaction potential as evidenced by histopathological examination, drug intake or other predisposing conditions. (3) Age less than 18 or more than 75 years. (4) Severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia. (5) Patients who had received any medications for LP.

All participants in the study were subjected to the following after giving consent: (1) Complete medical history and thorough physical examination with special details regarding onset, duration, site and morphology of LP lesions, and (2) psychiatric sheet. General Information Questionnaire. Each subject completed a general information form. Subjects reported information, including name, gender, address, home and work contact numbers.

The psychometric evaluation using DASS-42 was carried out, by the same investigator on all members of group 1 (before treatment of their oral lesions was initiated) and group 2 (the controls). DASS-42 is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 42 symptoms divided into three subscales of 14 items: Depression scale, anxiety scale, and stress scale. Participants rated the extent to which they had experienced each symptom over the previous week on a four-point scale ranging from 0 [did not apply to me at all] to 3 [applied to me very much, or most of the time].

Statistical analysis

The Student t test was used to determine statistical difference for both the groups and to evaluate for significant relationships among variables. A P value less than 0.05 was considered as statistical significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using the version 9.0 of the SPSS software.

Results

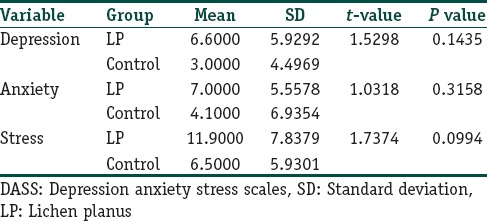

This study included 25 OLP patients and 25 control subjects. Both groups matched for age, sex, marital status, educational, occupational and socioeconomic level. Using DASS-42 scales for psychometric evaluation with the group of patients with OLP and the control group we obtained the following results: The patients with OLP were found to exhibit greater depression than control group on the depression scale, anxiety scale and stress scale [Table 1].

Table 1.

Summary statistics for DASS

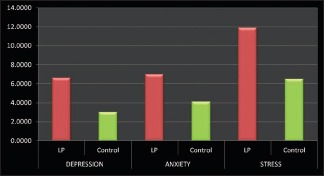

Psychological assessment using DASS-42 reveals LP patients showed higher frequency of psychiatric comorbidities like depression, anxiety and stress compared to the control group [Graph 1]. But we found that there were no statistical significant differences between the scores of the both LP patients and control groups in all the three variables.

Graph 1.

Difference in the depression, anxiety and stress levels in OLP and control patients

Discussion

The current investigation addresses two principal issues in relation to the DASS-42. First of these was carried out to assess depression, anxiety and stress levels in OLP patients. Second was to assess the reliability of the DASS-42 questionnaire. The factor structure originally described by Crawford et al. where DASS-42 was administered to a non-clinical sample, broadly representative of the general adult UK population in terms of demographic variables.[3]

In our study according to DASS scale: Depression level in LP patients was 13.8% compared to the control group 12.2%; Anxiety level in LP patients was 18.3% compared to the control group 13.9%. The present study showed that there is marginal increase in depression, anxiety in LP patients than control groups. Stress level in our study patients with OLP were found to exhibit increased stress level 25.4% than the control group 16.38%. However, the results were not statistically significant. This could be due to the smaller sample size in our study.

Dermatology has a distinct relation with psychosomatics as the skin has strong psychological implications. The skin is a complex system made up of glands, blood vessels, nerves and muscle elements, many of which are controlled by the autonomic nervous system and can be influenced by psychological stimuli. These have the capacity to cause autonomic arousal and capability of affecting the skin and the development of various skin disorders. Clinical studies have shown that psychological stress can cause suppression of killer T cells and macrophages, both of which play important roles in skin-related immune reactions.[5] Field described the skin as the “shock organ” for emotional stress, manifesting in the form of several skin diseases. Clinical observations have identified psychological stress as either precipitating, aggravating or prolonging many skin diseases and the psychosomatic aspects of many disorders.[6]

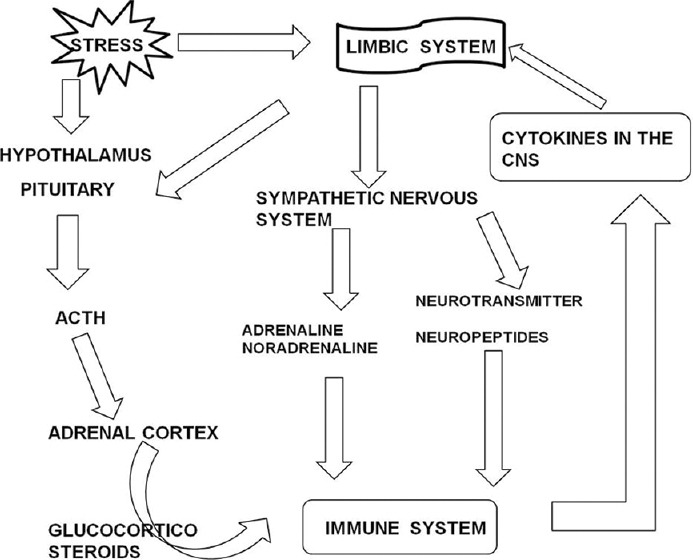

A complex multidirectional communication pathway involving the endocrine, immune and central nervous systems the skin maintains internal homeostasis. Brazzini et al. proposed the “an active neuro-immuno-endocrine interface” or neuroendocrine organ, exhibiting multidirectional and local communication, which is made possible by the production in the skin of cytokines, hormones and neurotransmitters, and anatomical links between the central nervous system (CNS) and skin. In addition, circulating immune cells, recruited in the skin, express receptors for a variety of neuropeptides, cytokines, neurotransmitters and hormones, identical to those expressed centrally, allowing the CNS to communicate with the skin. This means that systemic signals affecting the skin initiate a flow of information between this and other organs, leading to modulation of local immune activity, vascular functions, sensory reception, thermoregulation, exocrine secretion and maintenance of skin barrier integrity[7] [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Simplified overview of the channels of communication between the immune, endocrine and central nervous (CNS) systems in the stress response. (Brazinni et al. 2003)

LP is described as an adult disease. The typical age of presentation is between 30 and 60 years. Exact etiology of the LP is unknown, but it has been demonstrated that degeneration of the epithelial basal layer, resulting from a change in cell-mediated immune response, has a significant role in the pathogenicity of the lesion.[8] Therefore, any factor that can influence the cell-mediated immune response can have a role in the development of the disease. Factors such as stress and psychological problems, especially depression and anxiety, have been mentioned as etiologic factors in LP but there is still controversy concerning the role of stress as a major or minor etiologic factor in the pathogenicity of LP[9] [Figures 2 and 3].

Figure 2.

Erosive lichen planus on buccal mucosa

Figure 3.

Reticular lichen planus on buccal mucosa

Exacerbations of OLP have been linked to the periods of psychological stress and anxiety. Ivonavaski et al. proposed that prolonged emotive stress in OLP Patients has been proposed to lead to psychosomatization which in turn may contribute to the initiation and clinical expression of OLP and also suggested that psychosocial and emotional stress is one possible factor that may precipitate reticular OLP to transform to the erosive form.[10]

Different studies have been done for the evaluation of the relationship between OLP and psychiatric disorders. In 1961, Altman and Perry conducted a study on of 197 patients with LP, which revealed that “10% were aware of a precipitating stressful incident at the onset of their LP.” Andreasen pointed out in 1968 that patient with LP were found to be in conditions of stress, anxiety, and emotional changes. Colella et al. conducted a study in 1993 using different psychiatric tests such as “General Health Questionnaire,” “Hamilton Anxiety Scale,” “Melancholia scale, depression,” “Hamilton Depression Scale” demonstrated that OLP patients had higher depression and Anxiety score. McCartan noticed that out of 50 patients with OLP, tendency toward anxiety was in 50% of the cases, but depression scores were minimal and it could not be related to any specific clinical pattern of OLP.[11]

Other study showed that 63.6% of LP patients had psychiatric symptoms with mixed anxiety and depression being the most frequent (15.7%), followed by social phobia (12.9%), panic symptoms (11.4%), obsessive compulsive predominantly obsession thoughts and ruminations (10%), and dysthymia (5.7%) arranged in order.[1] A study conducted on 600 patients with LP, Shklar pointed the stress is a common factor.[11] In contrast to these studies that show stress, anxiety, and depression had a positive effect on OLP, some studies didn’t find any positive association between stress and OLP.

In one study, involved 100 patients with OLP and control subjects were subjected to the following psychometric tests to both groups: Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Cartel Personality Questionnaire 16PF, Hassanyeh Rating of Anxiety-Depression-Vulnerability, Beck Depression Inventory, Raskin Depression Screen, and Covi Anxiety Screen. Despite the higher anxiety scores observed in patients with OLP, it was not established that the observed psychological alterations constitute a direct etiologic factor of OLP, nor was it established that such alterations are a consequence of OLP and its lesions.[11]

Several studies were conducted using the DASS-42 Questionnaire. Nieuwenhuijsen et al. conducted a study showing that the psychometric properties of the DASS are suitable for use in an occupational health care setting. The DASS can be helpful in ruling out anxiety disorder and depression in employees with mental health problems.[4] A study was conducted by Ramli et al. to validate the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales 21-item (DASS-21) Bahasa Malaysia (BM) version among clinical subjects who were diabetic patients. DASS 21-item is a modified and shorter version. The results of this study entrenched the evidence that the BM DASS-21 had excellent psychometric properties and therefore it is suitable to be used for the Malaysian clinical population.[12] A study conducted by Crowford et al. where the DASS was administered to a non-clinical sample, broadly representative of the general adult UK population in terms of demographic variables. It was found that the reliability of the DASS was excellent, and the measure possessed adequate convergent and discriminate validity. The DASS is a reliable and valid measure of the constructs it was intended to assess. The utility of this measure for UK clinicians is enhanced by the provision of large sample normative data.[3]

OLP is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by relapses and Remissions. There is currently no cure for OLP. Treatment is aimed primarily at reducing the length and severity of symptomatic outbreaks. Topical steroids are the first-choice agent for the treatment of symptomatic, active OLP. Other topical agents that have been used in cases resistant to topical steroids include retinoids, cyclosporine, and tacrolimus. Oral and topical psoralen with a low dose of UVA is effective in treating OLP of various forms, but it seems to have too many side effects. Surgical excision, cryotherapy, CO2 laser, and ND: YAG laser have all been used in the treatment of OLP. In general, surgery is reserved to remove high-risk dysplastic areas.[13]

Role of psychotherapy in the treatment of OLP

Patient education: Inform patients with OLP about the chronicity of OLP and the expected periods of exacerbation and quiescence and its potentially increased risk of oral cancer

Eliminate smoking and alcohol consumption. Eat a nutritious diet, including fresh fruit and vegetables, because this may help reduce the risk of oral cancer[14]

The therapeutic intervention should aim at integrating two objectives: The resolution of the symptoms like elimination of mucosal erythematic lesion, ulceration, pain and the patient's personal development, taking into account the patient's needs. But there are different phases in the therapy and the patient can develop from wanting to being rid of a symptom to being more autonomic, increasing their assertiveness and to developing their full of treatment potential

Questionnaires: Including sleep disturbances, appetite, mood, depression, anxiety, stress and quality of life. This also helps to access the patient's emotions, how the patient talks about their family, their starting point, and emotions about unresolved issues such as mourning, privileged ties, breaks, losses, information on early death in the family, alcoholism, divorces, and recent difficult events These can help to define more accurately the problem and the consequences of the disease. They are very important as they contribute to better understand diseases and their connections with mental health. It is therefore important to correctly validate the used questionnaires in the language of the country where the study is carried out

The well-informed dentist needs openness and communication skills. They should have knowledge about neuroleptics and antidepressant medications and the ability to recognize and refer patients needing psychological help.[15]

Conclusion

LP is a psychosomatic disease. Higher frequency of psychiatric symptoms, poor quality of life, higher level of anxiety and neuroendocrine and immune dysregulations all these factors will enhance the exacerbation of the disease.

This study has provided evidence that the DASS-42 questionnaire is internally consistent and valid measures of depression, anxiety, and stress. Similar studies with larger sample size and comparing severity of OLP lesions with psychological status are recommended and use locally translated and adapted version of the scale. The present study used a small sample which might have contributed to low correlation coefficients obtained in this research. DASS-42 Questionnaire can also be used to determine the level of anxiety, stress and depression in diseases of the oral mucosa like recurrent apthous stomatitis, burning mouth syndrome and TMD disorders. Psychiatric evaluation can be considered for patients with OLP with routine treatment protocols recommended.

What is new?

DASS-42 is a self report questionnaire consists of 42 symptoms divided into three subscales of 14 items: Depression scale, anxiety scale, and stress scale. The DASS is a reliable and valid measure of the constructs it was intended to assess.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Tawil M, Sediki N, Hassan H. Psychobiological aspects of patients with lichen planus. Curr Psychiatr. 2009;16:370–80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scully C, Beyli M, Ferreiro MC, Ficarra G, Gill Y, Griffiths M, et al. Update on Oral Lichen Planus: Etiopathogenesis and Management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:86–122. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford JR, Henry JD. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS): Normative data and latent structure in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2003;42:111–31. doi: 10.1348/014466503321903544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieuwenhuijsen K, de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, Blonk RW, van Dijk FJ. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS): Detecting anxiety disorder and depression in employees absent from work because of mental health problems. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:77–82. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papadopoulos L, Bor R. Leicester, UK: BPS; 1999. Psychological Approaches to Dermatology. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field T. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. Touch Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brazzini B, Ghersetich I, Hercogova J, Lotti T. The neuro-immuno-cutaneous-endocrine network: Relationship between mind and skin. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:123–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8019.2003.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao ZZ, Savage NW, Sugerman PB, Walsh LJ. Mast cell/T cell interactions in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:189–95. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2002.310401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akay A, Pekcanlar A, Bozdag KE, Altintas L, Karaman A. Assessment of depression in subjects with psoriasis vulgaris and lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:347–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ismail SB, Kumar SK, Zain RB. Oral Lichen Planus and Lchenoid Reactions. Etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and malignat transformation. J Oral Sci. 2007;49:89–06. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.49.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rojo-Moreno JL, Bagán JV, Rojo-Moreno J, Donat JS, Milián MA, Jiménez Y. Psychologic factors and oral lichen planus: A psychometric evaluation of 100 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:687–91. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramli M, Salmiah MA, Nurul Ain M. Validation and psychometric properties of Bahasa Malaysia version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS) among diabetic patients. Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;18:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahebjamee M, Arbabi-Kalati F. Management of oral lichen planus. Arch Iran Med. 2005;8:252–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shekar C, Ganesan S. Oral Lichen Planus. J Dent Sci Res. 2001;2:62–87. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poot F, Sampogna F, Onnis L. Basic knowledge in psychodermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:227–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]