Abstract

Background:

A number of treatments for reducing the appearance of acne scars are available, but general guidelines for optimizing acne scar treatment do not exist. The aim of this study was to compare the clinical effectiveness and side effects of fractional carbon dioxide (CO2) laser resurfacing combined with punch elevation with fractional CO2 laser resurfacing alone in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.

Materials and Methods:

Forty-two Iranian subjects (age range 18–55) with Fitzpatrick skin types III to IV and moderate to severe atrophic acne scars on both cheeks received randomized split-face treatments: One side received fractional CO2 laser treatment and the other received one session of punch elevation combined with two sessions of laser fractional CO2 laser treatment, separated by an interval of 1 month. Two dermatologists independently evaluated improvement in acne scars 4 and 16 weeks after the last treatment. Side effects were also recorded after each treatment.

Results:

The mean ± SD age of patients was 23.4 ± 2.6 years. Clinical improvement of facial acne scarring was assessed by two dermatologists blinded to treatment conditions. No significant difference in evaluation was observed 1 month after treatment (P = 0.56). Their evaluation found that fractional CO2 laser treatment combined with punch elevation had greater efficacy than that with fractional CO2 laser treatment alone, assessed 4 months after treatment (P = 0.02). Among all side effects, coagulated crust formation and pruritus at day 3 after fractional CO2 laser treatment was significant on both treatment sides (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Concurrent use of fractional laser skin resurfacing with punch elevation offers a safe and effective approach for the treatment of acne scarring.

Keywords: Acne scars, fractional carbon dioxide laser, punch elevation

What was known?

A number of treatments are available that reduce the appearance of acne scars, but general guidelines for optimizing acne scar treatment are unavailable.

Introduction

Nearly 1% of people suffer acne scars.[1] Reported prevalence rates of acne vary from 35% to more than 90% in adolescents.[2] Scarring can result from inflammatory damage to connective tissue of the skin affected by acne. Eighty to ninety percent of people with acne scars have associated loss of collagen (atrophic scars), whereas a minority exhibit hypertrophic scars and keloids.[3,4]

Severe scarring caused by acne is associated with physical and psychological distress, particularly in young adults, and often results in decreased self-esteem and diminished quality of life.[5]

Unfortunately, acne scarring can be a difficult problem to address satisfactorily, and treatment usually requires the use of several different approaches over multiple sessions.[6,7,8,9]

A number of treatments are available that reduce the appearance of acne scars, but general guidelines for optimizing acne scar treatment are unavailable. There are multiple management options, both medical and surgical, and treatment with laser devices achieve significant improvement.[3] In fact, facial resurfacing with fractional ablative lasers currently appears to be one of the most effective treatment options for facial scars.[10,11] These lasers abrade the surface of the skin and also help tighten the collagen fibers underneath. Fractional ablative lasers treat only a ‘fraction,‘ or column, of the affected skin, leaving intervening areas of skin untreated. These untreated areas help to achieve rapid re-epithelialization of the skin, and minimize the chance of prolonged and serious adverse effects.[12]

Punch elevation is another common treatment approach for acne scarring. The punch instrument is a circular blade which is used for many diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in different medical and surgical specialties.[13] Punch elevation may entail punch excision of a small acne scar with a punch biopsy instrument of equal or slightly greater diameter. This method is used on deep boxcar scars that have sharp edges and bases that appear normal. In the punch elevation procedure, the same tool used in punch excisions is used to remove only the base (not the walls) of the scar. After the skin heals, it is more even and the pitted or pockmarked look is greatly reduced. When the scar tissue base has been sufficiently punched, the base of the scar becomes parallel to its outline or the outer walls surrounding the scar, meaning the scar base is elevated. This elevation makes the scar appear much less deep.[14]

A comparative side-by-side clinical study on the efficacy and safety of combining fractional carbon dioxide (CO2) resurfacing with punch elevation for the treatment of acne scars has not been previously conducted. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the clinical effectiveness and side effects of fractional CO2 laser resurfacing combined with punch elevation with fractional CO2 laser resurfacing alone in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Forty-two Iranian patients aged 18–55 years with Fitzpatrick skin types III to IV and moderate to severe atrophic acne scars on both cheeks, as assessed using the Goodman and Baron grading scale,[15] were enrolled in the study.

The Isfahan University of Medical Sciences Ethical Committee, Isfahan, Iran, approved the study protocol. The trial was registered with the code IRCT2014080218647N1 in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, which is a primary registry in the World Health Organization (WHO) Registry Network.

Patients signed an informed consent form for participation in the study. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, lactation, active inflammatory acne, immunocompetence, history of deep chemical peeling or filler injection in the previous 6 months, history of hypertrophic scars and keloids, use of isotretinoin in the previous 6 months, allergy to anesthesia, active infection in the treatment area, premalignant or malignant lesions in the treatment area, bleeding tendencies, and history of herpes simplex or herpes zoster infection on the face.

The researchers determined which side of the patient's face was to be treated using the 10600-nm fractional CO2 laser alone (M×7000/Stamp Type, Daeshin, South Korea) and with the fractional CO2 laser plus punch elevation (2.5–3 mm biopsy disposable punches) using random allocation software. The assignment sequence was concealed in opaque envelopes. Treatment was performed in an outpatient setting.

Study intervention

Our approach to treatment of acne scars consisted of two operative steps. Initially, punch elevation using 2.5 or 3 mm biopsy punches was performed on one side of the face. Secondly, 24 h after punch elevation, a full face CO2 laser treatment session was performed. A second full face laser treatment session was performed 4 week later. The laser device used on each side of the face was the same in the two treatment sessions. Standardized digital photography was performed using a camera (CANON: 8.5 megapixels.). Anesthetic cream (2.5% lidocaine/prilocaine, XYLA-P Tehran Chemie Pharmaceutical Company, Iran) was applied to the treatment area under occlusion 1 h before laser treatment. The researcher performed the intervention on each side of the patient's face according to the prepared randomized sequence. The parameters set on the fractional CO2 laser were 12-14 W, 48-56 mJ/MTZ/pulse, 13% density, pulse interval 35 ms. Patient skin response was used to set the appropriate energy for the laser treatment. Patients received prophylactic antibiotic and antiviral medications 1 day prior to treatment and continued the medications for 1 week. After treatment, patients applied an SPF 30 sunscreen cream with oil-free base and washed their face with mild soap.

Clinical evaluation

Clinical evaluation was done 1 and 4 months after the second treatment session was completed. First, two dermatologists blinded to treatment side evaluated clinical improvement of acne scars by comparing the photographs taken before treatment with those taken 1 and 4 months after the last treatment session. The grading scale was structured as follows: 1 = <25% (minimal) improvement, 2 = 25–50% (moderate) improvement, 3 = 51–75% (good) improvement, 4 = >75% (excellent) improvement. Second, patients were asked to evaluate their satisfaction with the treatment using a visual analog scale (VAS; A rating of 0 was no satisfaction, and a rating of10 was the best possible satisfaction). Side effects, including pain score (0 – no pain, to 10 – the most pain), pruritus, erythema, edema, bleeding, burning, duration of facial erythema, facial dryness, infection, ulceration, scar formation, dyspigmentation, were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data were reported as means ± SD. Statistical comparison of the effectiveness and side effects of the two treatment sides was conducted using t-tests. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Forty-two patients (100%; 28 with Fitzpatrick skin type III, 14 with type IV; 23 males, 19 females) completed the two treatment sessions, and all were followed up for 4 months after the last treatment session. Acne scars varied from depressed, small, and icepick to larger and concave areas. Most patients had multiple morphological types of scars. The mean ± SD age of patients was 23.4 ± 2.63 years.

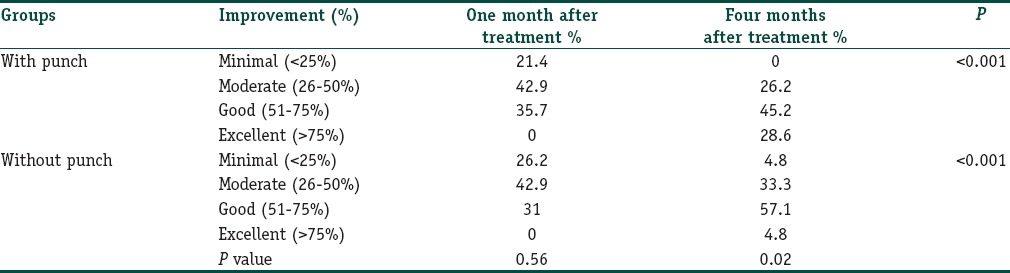

Clinical improvement of facial acne scarring was assessed by two dermatologists blinded to treatment condition. The assessment of the two dermatologists was not significantly different 1 month after treatment (P = 0.56; Table 1).

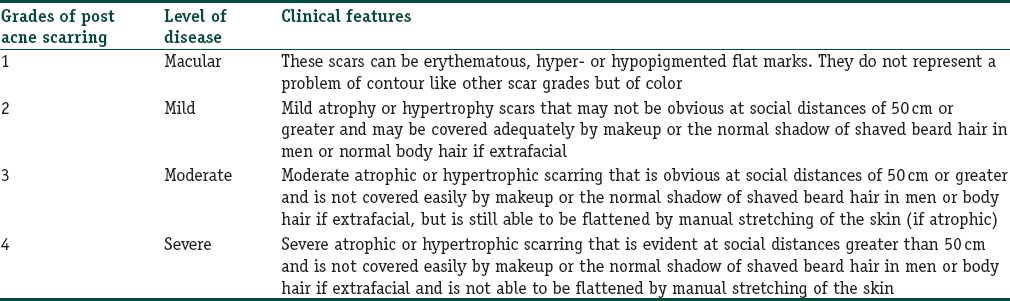

Table 1.

Global acne scarring classification: Type of scars making up the classification grades

Their evaluation indicated that fractional CO2 laser treatment combined with punch elevation was more efficacious than fractional CO2 laser treatment alone at 4 months after treatment (P = 0.02; Table 2; Figures 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Scar improvement percentage in two methods 1 and 4 months post-treatment

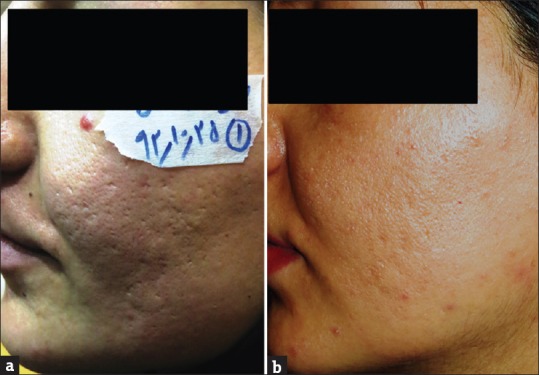

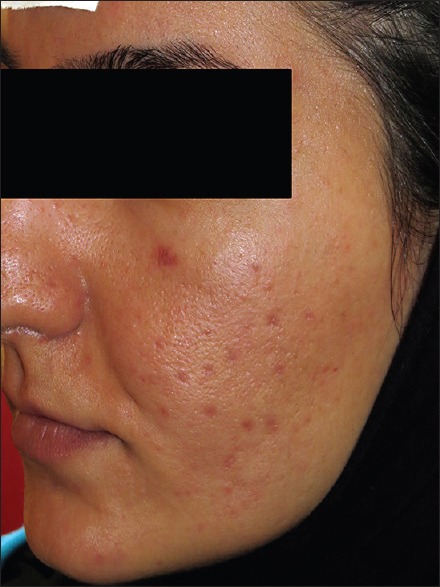

Figure 1.

(a) Atrophic acne scars in 27-year-old female in the check before treatment. (b) Follow-up 4 months after treatment of fractional resurfacing plus punch elevation

Figure 2.

(a) Atrophic acne scars in 32-year-old patient in the check before treatment. (b) Follow-up 4 months after treatment of fractional resurfacing plus punch elevation

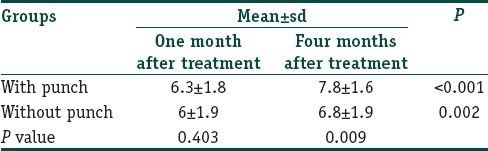

Patient satisfaction surveys conducted 4 months after the end of the study revealed that there was a statistically significant difference in mean acne scar improvement score between the two treatment approaches (P = 0.009; Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of patient satisfaction rates in two methods, 1 and 4 months post-treatment

There was no statistically significant difference in mean acne scar improvement score between the different types of acne scar at the end of study (P = 0.75).

We used the Mann–Whitney test to evaluate differences in percentage of improvement between sexes, but there was no statistically significant difference between them on either treatment side (P > 0.05).

Additionally, at-test did not show a significant difference in percentage of improvement across in types on either treatment side (P > 0.05).

In 61.9% of the patients, improvement was good or excellent 4 months after the end of the study [Figures 1 and 2].

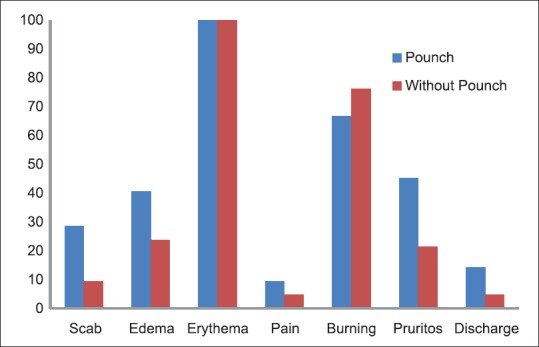

The most commonly reported adverse effect was transient erythema [Figure 3] and crusting lasting for an average of 3–4 and 4–7 days, respectively. Transient post-treatment burning and erythema was seen in all patients on day 3 after fractional CO2 laser treatment on both treatment sides, but this resolved without any treatment.

Figure 3.

Mild post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation after 1 month of treatment

Mild post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation was observed in 21.4% of subjects (n = 9; P = 1) 1 month after treatment. This lasted no longer than 6 months and resolved gradually after 2–3 months. Hypopigmentation was not evident in any patient at any of the follow-up visits.

The pain score on the side that had both punch elevation and fractional CO2 laser treatment was higher than on the side that had fractional CO2 laser treatment only, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.34) and the pain did not persist more than a few hours.

Among all side effects, coagulum formation and pruritus 4 days after fractional CO2 laser treatment was significant on both sides (P < 0.05; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Side effect on day 3

No infections, ulceration, or scar formation associated with the use of the laser and no hypertrophic scarring following punch elevation were observed.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that ablative 10,600 nm fractional CO2 laser treatment combined with punch elevation is an effective treatment approach for acne scars in Asian patients. Good to excellent improvement was seen in about 60% of the acne scars.

Fractional CO2 laser treatment was developed in an effort to overcome the short comings of the traditional ablative lasers and non-ablative fractional lasers. Its histological and clinical effect in vivo was first reported by Hantash et al.[16]

Because of the varying types and severity of acne scarring, it is important to keep in mind that the treatment of scarring in any individual patient will likely require some combination of techniques. For example, this may include resurfacing techniques to address superficial irregularities, dermal fillers to replace lost volume in large atrophic areas, and surgical procedures, such as punch excision, to remove deep boxcar or large icepick scars.[17]

Some types of acne scars cannot be comprehensively repaired using conventional acne treatment methods, and some types cannot be effectively corrected by a single treatment modality, due to wide variation in their depth and width.[18]

A number of studies have been performed that have demonstrated the benefits of fractional CO2 laser treatment on acne scarring and have promoted the advantage of selective ablation.[19,20,21]

Although CO2 lasers allow for more precise ablation control, some deeper scars require multiple treatment passes that could produce additional scarring.[21]

Another limitation of the CO2 laser is its depth of penetration. The laser is only effective in approximately the upper 30 μm of the skin, which limits the area that can be treated by the laser.[21]

Johnson (1986) reported punch techniques for the treatment of deep acne scars using cutaneous punches and repair with steri-strips, or other methods.[22] Punch excision and punch elevation remain important surgical options for certain types of atrophic acne scars.[14]

Punch techniques remain the gold standard for large, deep boxcar, and icepick scars.[14]

These punch techniques often entail punch excision of a single small acne scar with a punch biopsy instrument of equal or slightly greater diameter. This method is used on deep boxcar scars that have sharp edges and bases that appear normal. In the punch elevation procedure, the same tool used in punch excisions is used to remove only the base (not the walls) of the scar.

This method reduces the risk of producing texture or color differences and additional scarring.

The punch elevation method is better for improving deep acne scars than depth resurfacing is, and it can be combined with the shoulder technique or depth resurfacing depending on the type of acne scar.[23] Therefore, punch elevation techniques have increased the efficacy of treatment of atrophic acne scars.[15]

In punch elevation, after the punch is performed the base is elevated and sutured flush with the surrounding normal-appearing skin, and then allowed to heal in place.[11]

An obvious advantage to the combination of punch elevation and laser ablation is that the laser acts superficially and punch elevation eliminates the need for multiple laser passes over deep scars.[24]

Another advantage of combining punch elevation with laser ablation is the ability of the laser to effectively ablate the superficial portion of the scar and remove the epidermal component. This means that punch grafting is not necessary when using this technique, which eliminates complications of transplantation that often require redo grafting.[24]

In our study, by combining laser skin resurfacing and punch elevation, all patients improved without any infection or additional scarring.

Though fractional CO2 laser procedures used in isolation can produce very satisfactory results, we found that the combination of multiple approaches, such as the combination of CO2 laser treatment with punch elevation, may be necessary to optimize treatment outcome.

A larger sample size with a longer period of follow-up may yield even more favorable results.

Conclusion

Fractional CO2 laser treatment in combination with punch elevation improves outcome in the treatment of facial acne scars. This combination provides the benefit of increased patient satisfaction without an increase in side effects.

What is new?

Fractional CO2 laser treatment in combination with punch elevation improves outcome in the treatment of facial acne scars.

Footnotes

Source of support: Skin Diseases and Leishmaniasis Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan Iran

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Cunliffe WJ, Gould DJ. Prevalence of facial acne vulgaris in late adolescence and in adults. Br Med J. 1979;1:1109–10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6171.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stathakis V, Kilkenny M, Marks R. Descriptive epidemiology of acne vulgaris in the community. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38:115–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1997.tb01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabbrocini G, Annunziata MC, D’Arco V, De Vita V, Lodi G, Mauriello MC, et al. Acne scars: Pathogenesis, classification and treatment. Dermatol Res Pract 2010. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/893080. 893080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faghihi G, Rakhshanpour M, Abtahi-Naeini B, Nilforoushzadeh MA. The efficacy of 5% dapsone gel plus oral isotretinoin versus oral isotretinoin alone in acne vulgaris: A randomized double-blind study. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:177. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.139413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loney T, Standage M, Lewis S. Not just ‘skin deep’: Psychosocial effects of dermatological-related social anxiety in a sample of acne patients. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:47–54. doi: 10.1177/1359105307084311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob CI, Dover JS, Kaminer MS. Acne scarring: A classification system and review of treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:109–17. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.113451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman G. Post acne scarring: A review. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2003;5:77–95. doi: 10.1080/14764170310001258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadick NS, Palmisano L. Case study involving use of injectable poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) for acne scars. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:302–7. doi: 10.1080/09546630902817879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadove R. Injectable poly-L: -lactic acid: A novel sculpting agent for the treatment of dermal fat atrophy after severe acne. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33:113–6. doi: 10.1007/s00266-008-9242-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geronemus RG. Fractional photothermolysis: Current and future applications. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:169–76. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivera AE. Acne scarring: A review and current treatment modalities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:659–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hantash BM, Mahmood MB. Fractional photothermolysis: A novel aesthetic laser surgery modality. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:525–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AlGhamdi KM, AlEnazi MM. Versatile punch surgery. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15:87–96. doi: 10.2310/7750.2011.10002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman GJ, Baron JA. The management of postacne scarring. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1175–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: A qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hantash BM, Bedi VP, Kapadia B, Rahman Z, Jiang K, Tanner H, et al. In vivo histological evaluation of a novel ablative fractional resurfacing device. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:96–107. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Daniel TG. Multimodal management of atrophic acne scarring in the aging face. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35:1143–50. doi: 10.1007/s00266-011-9715-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whang KK, Lee M. The principle of a three-staged operation in the surgery of acne scars. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:95–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan XH, Zhong SX, Li SS. Comparison study of fractional carbon dioxide laser resurfacing using different fluences and densities for acne scars in Asians: A randomized split-face trial. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:545–52. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjorn M, Stausbol-Gron B, Braae Olesen A, Hedelund L. Treatment of acne scars with fractional CO2 laser at 1-month versus 3-month intervals: An intra-individual randomized controlled trial. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:89–93. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magnani LR, Schweiger ES. Fractional CO2 lasers for the treatment of atrophic acne scars: A review of the literature. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16:48–56. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2013.854639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson WC. Treatment of pitted scars: Punch transplant technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:260–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1986.tb01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koo SH, Yoon ES, Ahn DS, Park SH. Laser punch-out for acne scars. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2001;25:46–51. doi: 10.1007/s002660010094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grevelink JM, White VR. Concurrent use of laser skin resurfacing and punch excision in the treatment of facial acne scarring. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:527–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]