Abstract

Background:

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition that can have a negative impact on a patient's quality of life. Few studies have been conducted to assess the clinical characteristics of the disease and quality of life of the patients, especially in tropical countries.

Aims and Objectives:

The aim of this study was to demonstrate the clinical characteristics and quality of life of patients with seborrheic dermatitis in Thailand.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was performed at a university-based hospital and tertiary referral center in Bangkok, Thailand. The validated Thai version of the dermatology life quality index (DLQI) was used to evaluate patients’ quality of life.

Results:

A total of 166 participants were included. One hundred and forty-seven patients (88.6%) experienced multiple episodes of the eruption. The mean of outbreaks was 7.8 times per years, ranging from once every 4 years to weekly eruption. The most common factor reported to aggravate seborrheic dermatitis was seasonality (34.9%), especially hot climate. The mean (SD) of the total DLQI score was 8.1 (6.0) with a range of 0 to 27. There was no statistically significant difference between the two DLQI categories regarding duration of disease, extent of involvement, symptoms or course of the disease.

Conclusion:

Although mild and asymptomatic, seborrheic dermatitis can have a great impact on the quality of life. Youth, female gender, and scalp lesions were significantly associated with higher DLQI scores.

Keywords: Characteristics, DLQI, quality of life, seborrheic dermatitis

What was known?

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common chronic inflammatory skin that can have a negative impact on a patient's quality of life. Harsh environment (low temperature and humidity in winter) on skin barrier is responsible for high frequency of seborrheic dermatitis in temperate countries.

Introduction

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition affecting 11.6% of the general population and up to 70% of infants in the first few months of life.[1] It can impact the psychology and quality of life of those suffering from chronic relapsing course.[2,3,4] Chronic skin diseases can have physical and emotional impact on one's qualities of life which include discomfort, stigmatization, loss of self-esteem, and limitations in social activities.[5] Some even have a negative impact on the quality of life comparable to that of cardiovascular diseases.[6]

Scalp pruritus and scales of seborrheic dermatitis may form social stigma and cause isolation from the society. Facing these stressful circumstances was proposed to increase depressive symptoms in this group of patients.[2] However, limited studies have been conducted to access the clinical characteristics of the disease and quality of life of the patients. Few studies[3,7] have been conducted in temperate climates where clinical characteristics of patients may differ from those in tropical countries. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the clinical characteristics and quality of life of patients with seborrheic dermatitis in Thailand, which has a tropical climate.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was performed at a university-based hospital and tertiary referral center in Bangkok, Thailand, between May 2013 and June 2014. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Participants

Patients who were older than 18 years[3] and had been diagnosed with seborrheic dermatitis at any site were included. Diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis was made clinically by presentation of erythematous patches with greasy scales on predilection areas including the scalp, face, ears, presternal or intertriginous areas.[8] Additional laboratory investigations including potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination or antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were performed in case of uncertain diagnosis to rule out other dermatologic diseases. Doubtful cases and those with other concomitant dermatoses were excluded. All patients gave written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Instruments

The facial skin types were classified as dry, normal, oily, or combination skin.[9] The skin type-related symptoms, which correlate with the causal sebum level,[9] were used to classify facial skin types. The questions included “feeling of dryness in the face,” “feeling tightness after washing,” “feeling coarseness after washing,” “feeling oiliness in the face,” “easy washing out of make-up” and “feeling difference in facial oiliness in face.”[9]

The validated Thai version of the dermatology life quality index (DLQI)[10] was used to evaluate patients’ quality of life. The formal permission to use the DLQI score was kindly given to Dr. Kulthanan by Dr. Andrew Y. Finlay. All patients were asked to complete the questionnaire by themselves. The DLQI questionnaire comprised 10 questions with 6 domains, including symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relationships, and treatment difficulties. The DLQI score was grouped into five categories: 0–1 = no effect, 2–5 = small effect, 6–10 = moderate effect, 11–20 = very large effect, and 21–30 = extremely large effect.[11] The DLQI score was further classified into two categories. A DLQI score of 0 to 5 was interpreted as no or small effect on quality of life. A score of more than 5, which equate to moderate to severe effect on quality of life, was determined as a high DLQI score.

Procedures

After receiving informed consent, patients were asked to complete the DLQI questionnaire by themselves. The demographic data and clinical information (i.e., underlying disease, personal and family history of atopy, age of onset, course of disease, and aggravating factors) were collected. Physical examination was performed by one dermatologist to evaluate the lesion and extent of involvement.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0. Descriptive statistics, e.g., mean, median, minimum, maximum, and percentages were calculated to describe the demographic data. The categorical variables were compared using Pearson's Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test when appropriate. Demographic data, clinical data and the DLQI score were compared using the Pearson's Chi-squared test and the Mann–Whitney U test for categorical and continuous data, respectively. The mean values were compared using ANOVA. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic data

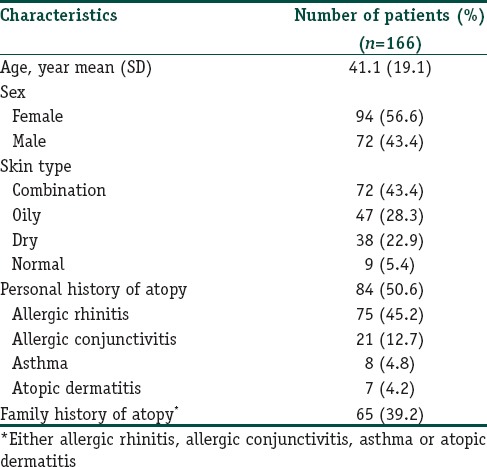

A total of 166 participants were included. There were 94 females (56.6%) and 72 males (43.4%). The mean (SD) age of patients was 41.9 (18.9) years, ranging from 18 to 89 years. The mean age at diagnosis was 35.5 (19.3) years. The median time elapsed since diagnosis was 3 years. The most reported facial skin type was combination skin, followed by oily skin. Eighty-four patients (50.6%) were reported having a personal history of atopy. The most common atopy reported was allergic rhinitis, followed by allergic conjunctivitis, asthma and atopic dermatitis, respectively. Sixty-five patients (39.2%) had a family history of atopy. Demographic data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of seborrheic dermatitis patients

Three patients (1.8%) in this study were infected with HIV. The mean CD4 immune cell count was 401 cells/mm3, ranging from 18 to 850 cells/mm3.

Clinical features

Of all the patients, 147 (88.6%) experienced multiple episodes of eruption, while 19 (11.4%) reported having the lesions for the first time. Of those who had chronic disease, 113 patients (68.1%) had an occasional exacerbation with a chronic recurrence, while 34 (20.5%) had a more persistent and continuous course. Among the chronic recurrent group, the median of outbreaks was six times per year, ranging from once every 4 years to weekly eruptions. The median eruption time was 2 weeks with a median interval of 1.5 months. Of those with continuous course, the median duration from onset was 3 years.

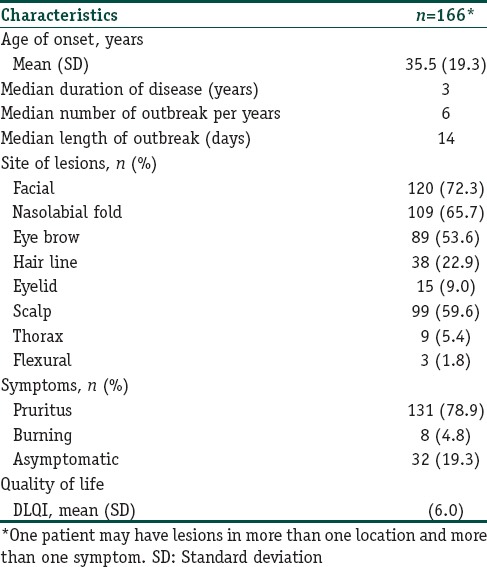

The most commonly affected area was the face (75.3%), followed by the scalp (59.%), the retroauricular area (7.8%), the upper chest (3%), and the upper back (2.4%). On the face, the nasolabial folds, eye brows, hair line, and eyelids were commonly involved. Rashes were rare on other areas, such as inguinal and axillae. Ninety-nine patients (59.6%) usually had localized lesions on one body part, while 67 patients (40.4%) had multiple sites of involvement. There was no difference in the extent of involvement, symptoms, or course of disease between the HIV and non-HIV infected groups.

Erythematous patches were found in all cases. Scale was noted in 95.2% of the patients while some treated cases had no scale. Most seborrheic dermatitis patients usually had symptoms of itchiness (78.9%) or burning (4.8%), while 19.3% were asymptomatic. Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of the seborrheic dermatitis patients.

Table 2.

Clinical features and quality of life of seborrheic dermatitis patients

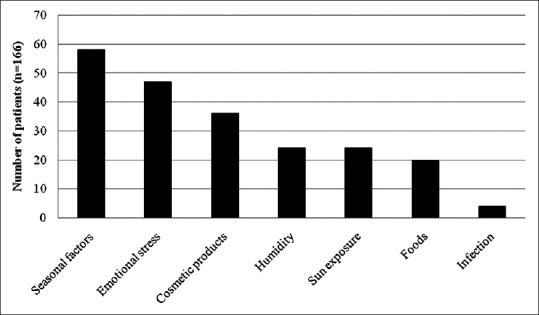

Of 166 participants, 138 (83.1%) reported that the outbreak was triggered by exogenous and/or endogenous factors. Variables reported to aggravate seborrheic dermatitis were seasonal factors (i.e., hot weather) (34.9%), emotional stress or sleep deprivation (28.3%), cosmetic products (21.7%), sweat and damp humidity (14.5%), sun exposure (14.5%), foods (12.0%), and infection (2.4%). Figure 1 shows aggravating factors that triggered seborrheic dermatitis.

Figure 1.

Aggravating factors of seborrheic dermatitis as reported by patients

Corticosteroids were used as a first-line therapy in most patients. One hundred and fifty-four patients (92.8%) were treated with mostly mildly potent topical corticosteroids. Moderately potent topical steroids were also used in recalcitrant cases or some anatomical areas such as the scalp. For alternative treatments, topical antifungal medication, tar shampoo, and topical calcineurin inhibitors were used in 51 patients (30.7%), 44 patients (26.5%) and 1 patient (0.6%), respectively.

Quality of life

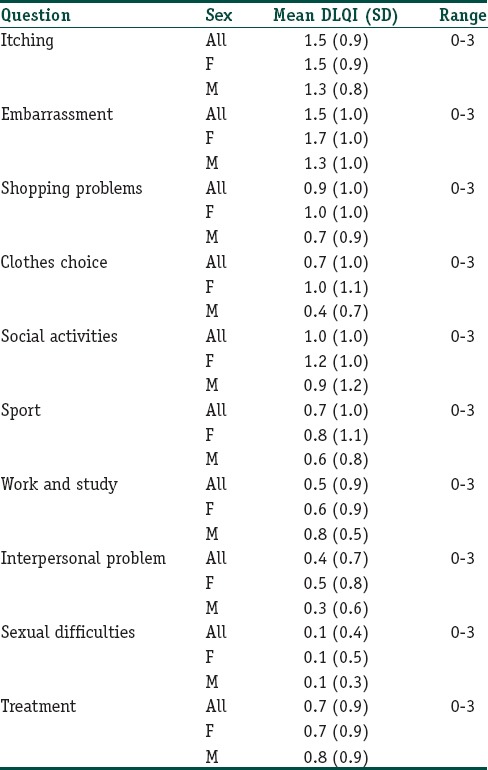

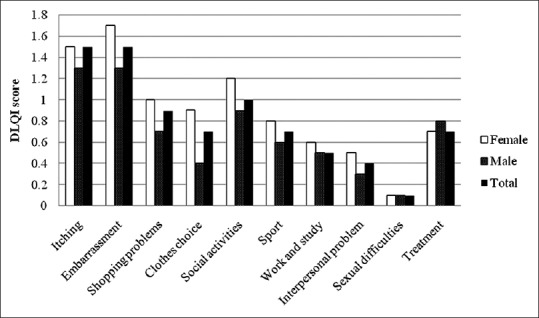

All patients completed all 10 questions of the DLQI questionnaire. The mean (SD) of the total DLQI score was 8.1 (6.0) with a range of 0 to 27. Six patients (3.6%) had a DLQI score more than 20, which implied extremely large effect on quality of life. Of these, some experienced only mild, asymptomatic, localized lesions. Table 3 and Figure 2 show the DLQI score of each question. Question 1 (symptom) and question 2 (embarrassment) had the highest mean DLQI score (1.5), while question 9 had the lowest mean score (0.1).

Table 3.

The dermatology life quality index (DLQI) score of each question

Figure 2.

The mean scores of each DLQI question

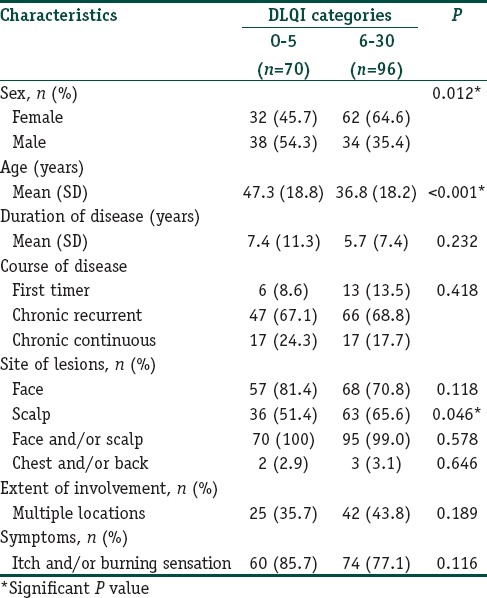

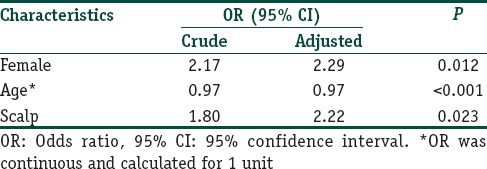

Table 4 shows characteristics of patients categorized by the DLQI score. There was no statistically significant difference between the two DLQI categories regarding duration of disease, extent of involvement, symptoms or course of the disease. Mean (SD) DLQI score of first timers, chronic relapsing and chronic persistent patients were no significant difference with the score of 8.1 (4.7), 7.7 (5.9) and 8.9 (7.3), respectively. Female gender, young age, and scalp lesions were significantly associated with a higher DLQI score. Gender, age, duration of disease, course of disease, site of lesions, extent of involvement and symptoms were included in a multiple logistic regression analysis; however, only the remaining factors associated with a high DLQI score are shown in Table 5. Females significantly scored higher than males in question 2 (embarrassment) and question 4 (clothing choice).

Table 4.

Characteristics of patients categorized by DLQI score

Table 5.

Multiple logistic regression model of factors associated with high DLQI score

Discussion

The prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis is unclear due to lack of validated diagnostic criteria.[12] Some publications report that seborrheic dermatitis is more common in men.[13,14] However, a population-based study in the United States revealed that the prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis was estimated to be higher in women (3%) than men (2.6%).[12,15] This paper also showed that most of seborrheic dermatitis patients in the study were female.

Seborrheic dermatitis has two peak prevalence: infantile and adult.[14] In adult seborrheic dermatitis, the peak prevalence is approximately 30 to 60 years of age.[3,14] The mean age of patients in this study was 41.9 (SD = 18.9) years. The mean age of onset was 35.5 (19.3). Regarding gender ratio, mean age of onset and median range of outbreak, the data was comparable to the previous study in Spain.[3]

The subjective facial skin type was found to be comparable to sebum production levels with the appropriate questions, and the sebum level was highest in the oily skin type, followed by combination, normal, and dry skin.[9] In this study, most patients had combination skin, followed by oily skin, dry skin, and normal skin. The role of seborrhea in seborrheic dermatitis is debatable. One study[16] demonstrated increased sebum production levels in seborrheic dermatitis patients, while others[17,18] found normal, or even decreased rates of sebum production in seborrheic dermatitis. Although the correlation between sebum levels and pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis is unclear, there is evidence that lipid composition in seborrheic dermatitis patients differs from unaffected controls.[13]

Half of patients in this study reported having a personal history of atopy. This involved either allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, asthma, or allergic dermatitis. In Thailand, the prevalence of allergic rhinitis and asthma in university students was reported to be up to 23–64% and 2–17%, respectively.[19,20,21,22] This implies that the prevalence of atopy is not elevated in seborrheic dermatitis patients.

Seborrheic dermatitis is more common in patients with Parkinson's disease, mood disorders, and those with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency virus syndrome (AIDS).[13] In HIV-infected individuals, the clinical severity of seborrheic dermatitis was more severe, especially in those with low CD4 counts.[12] Due to the small number of HIV patients in this study, we found no significant association between HIV infection and the extent of involvement, symptoms, or course of seborrheic dermatitis.

The course of seborrheic dermatitis in adults is variable. Some experience occasional exacerbation and others may have a more persistent course with frequent recurrences.[23] This study shows that most of patients experienced a chronic course (i.e., either chronic recurrent or persistent). The frequency of exacerbation ranged from as long as once in every 4 years to weekly recurrences. Median number of outbreak was six times per year, which is higher than three times per year reported in the study[3] from temperate climate.

In this study, a majority of patients had the triggering factors that aggravate seborrheic dermatitis, compared to 98.4% in the previous study.[3] The most common reported factor in this study was seasonal factor (mostly summer and hot climate), followed by stress. In contrast, study from temperate climate[3] reported stress/depression/fatigue to be the most common triggering factors followed by seasonal variables (worsens in winter and improves in summer). As there are variable in seborrheic dermatitis-related factors (UV radiation, humidity and temperature) during each season,[24] the different climates of the study locations may explain the discrepancy of these results. Harsh environment (low temperature and humidity in winter) on skin barrier is responsible for high frequency of seborrheic dermatitis in temperate countries.[3,24] Warmth and humid climate, facilitating pityriasis fungal growth, may trigger seborrheic dermatitis during summer month in Thailand. In addition, skin microorganisms, which are divergently colonized among patients from different region,[25,26,27] may effect on the growth of potential pathogens and contribute to the discrepancy of the health outcome. Although exposure to sunlight is thought to be beneficial in seborrheic dermatitis due to inhibition of Pityrosporum ovale and Langerhans cell suppression,[24,28] we found that sunlight was considered a triggering factor in some patients. Seborrheic dermatitis patients have an increased risk of skin irritation to sodium lauryl sulfate, which is used in cosmetics and household products.[13,29] In this study, cosmetic products were reported to be a triggering factor in 21.4% of patients. It should be noted that these triggering factors were subjectively reported by patients and a larger controlled study with objective clinical data should be further investigated.

In this study, the mean DLQI score of seborrheic dermatitis was 8.1 (SD = 6.0), which is higher than the score of 7.73 (SD = 5.3) that was previous published.[7] The mean DLQI score of 8.1 was almost comparable to HIV-infected patients who had a mean DLQI of 8.7.[30] Comparing to other dermatologic diseases in Thailand, the observed mean DLQI score for seborrheic dermatitis was higher than fungal infection (i.e., mean DLQI score of 6.5), but lower than acne (i.e., mean DLQI score of 10.6). Although there was no statistically significant difference between the two DLQI categories regarding duration of disease, extent of involvement, symptoms or course of the disease, this study showed that the DLQI score was significantly higher in women than in men and in younger patients than in elderly patients. Patients who had seborrheic dermatitis on the scalp also had significantly higher DLQI scores than those who had lesions on other areas. This is parallel to previous studies[3,7] that used scalpdex and DLQI questionnaires to evaluate the quality of life in patients who had scalp dermatitis, or seborrheic dermatitis with or without other concomitant skin diseases. Scales in scalp seborrheic dermatitis can be bothersome because of shedding flakes, which can be perceived as uncleanliness.[23] Social-image awareness may lead to a loss of self-esteem, a negative social image, and a greater negative impact on quality of life. Therefore, when determining treatment regimen for these specific groups of patient, a more aggressive regimen should be employed to quickly alleviate the disease and improve patients’ quality of life.

Conclusion

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common dermatologic disease with variable course and clinical severity. Geographic difference has some influences on clinical profiles of the disease. Although mild and asymptomatic, seborrheic dermatitis can have a great impact on quality of life and lead to loss of self-esteem and a negative social image, especially in young age group, female gender and scalp lesions.

What is new?

In contrast to study from temperate climate, warmth and humid climate trigger seborrheic dermatitis during summer month in tropical country. Although mild and asymptomatic, seborrheic dermatitis can have a great impact on quality of life, especially in young age group, female gender and scalp lesions.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Ms. Pimrapat Tengtrakulcharoen for her kind support.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Berk T, Scheinfeld N. Seborrheic dermatitis. P T. 2010;35:348–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oztas P, Calikoglu E, Cetin I. Psychiatric tests in seborrhoeic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:68–9. doi: 10.1080/00015550410021574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peyri J, Lleonart M. Clinical and therapeutic profile and quality of life of patients with seborrheic dermatitis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:476–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misery L, Touboul S, Vincot C, Dutray S, Rolland-Jacob G, Consoli SG, et al. Stress and seborrheic dermatitis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2007;134:833–7. doi: 10.1016/s0151-9638(07)92826-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed A, Leon A, Butler DC, Reichenberg J. Quality-of-life effects of common dermatological diseases. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2013;32:101–9. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprangers MA, de Regt EB, Andries F, van Agt HM, Bijl RV, de Boer JB, et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:895–907. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Wesołowska-Szepietowska E, Baran E. National Quality of Life in Dermatology Group. Quality of life in patients suffering from seborrheic dermatitis: Influence of age, gender and education level. Mycoses. 2009;52:357–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reider N, Fritsch PO. Other Eczematous Eruptions. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, editors. Dermatology. 1.3rd ed. New York: Elsevier; 2012. p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi CW, Choi JW, Youn SW. Subjective facial skin type, based on the sebum related symptoms, can reflect the objective casual sebum level in acne patients. Skin Res Technol. 2013;19:176–82. doi: 10.1111/srt.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulthanan K, Jiamton S, Wanitphakdeedecha R, Chantharujikaphong S. The validity and reliability of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) in Thais. Thai J Dermatol. 2004;20:110–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index 1992. [Last accessed on 2014 Aug 14]. Available from: http://www.dermatology.org.uk/quality/dlqi/quality-dlqi-info.html .

- 12.Naldi L, Rebora A. Clinical practice. Seborrheic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:387–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0806464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta AK, Bluhm R. Seborrheic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:13–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampaio AL, Mameri AC, Vargas TJ, Ramos-e-Silva M, Nunes AP, Carneiro SC. Seborrheic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1061–71. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson MT, Roberts J. Skin conditions and related need for medical care among persons 1-74 years. United States, 1971-1974. Vital Health Stat 11. 1978;212:i–v. 1-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.el-Mofty AM, Ismail AA, Abdel-Hay A, Kamel G, Nada M, Talaat M. Skin surface lipid excretion and blood lipids in seborrhoeic disorders. J Egypt Med Assoc. 1967;50:375–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgson-Jones IS, Mackenna RM, Wheatley VR. The surface skin fat in seborrhoeic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1953;65:246–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1953.tb13746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burton JL, Pye RJ. Seborrhoea is not a feature of seborrhoeic dermatitis. Br Med J. 1983;286:1169–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6372.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuchinda M. Prevalence of allergic diseases. Siriraj Gaz. 1978;30:1285–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vichayanond P, Sunthornchart S, Singhivannusorn V. Prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema among university students in Bangkok. Respir Med. 2002;96:34–8. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uthaisangsook S. Prevalence of asthma, rhinitis, and eczema in the university population of Phitsanulok, Thailand. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2007;25:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulthanan K, Jiamton S, Thumpimukvatana N, Pinkaew S. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: Prevalence and clinical course. J Dermatol. 2007;34:294–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Del Rosso JQ. Adult seborrheic dermatitis: A status report on practical topical management. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:32–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hancox JG, Sheridan SC, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB., Jr Seasonal variation of dermatologic disease in the USA: A study of office visits from 1990 to 1998. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenthal M, Goldberg D, Aiello A, Larson E, Foxman B. Skin microbiota: Microbial community structure and its potential association with health and disease. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:839–48. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thamlikitkul V, Santiprasitkul S, Suntanondra L, Pakaworawuth S, Tiangrim S, Udompunthurak S, et al. Skin flora of patients in Thailand. Am J Infect Control. 2003;31:80–4. doi: 10.1067/mic.2003.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson EL, Cronquist AB, Whittier S, Lai L, Lyle CT, Della Latta P. Differences in skin flora between inpatients and chronically ill outpatients. Heart Lung. 2000;29:298–305. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2000.108324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg M. Epidemiological studies of the influence of sunlight on the skin. Photodermatol. 1989;6:80–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Household Products Database. 2013. [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 16]. Available from: http://www.householdproducts.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/household/brands?tbl=chem and id=78 .

- 30.Kanmani CI, Udayashankar C, Nath AK. Dermatology Life Quality Index in patients infected with HIV: A comparative study. [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 16];Egypt Dermatol Online J. 2013 9:3. Available from: http://www.edoj.org.eg/vol009/0901/003/paper.pdf . [Google Scholar]