Abstract

Background:

Melasma is one of the most common and distressing pigmentary disorders presenting to dermatology clinics. The precise cause of melasma remains unknown. It is notably difficult to treat and has a tendency to relapse. Its population prevalence varies according to ethnic composition, skin phototype, and intensity of sun exposure. Due to its frequent facial involvement, the disease has an impact on the quality of life of patients.

Aims:

To study the clinico-epidemiological pattern, dermascopy, wood's lamp findings and the quality of life in patients with melasma.

Settings and Design:

Observational/descriptive study.

Materials and Methods:

Patients with melasma were screened. History, clinical examination, Wood's lamp examination (WLE) and dermoscopy were done. Severity of melasma was assessed by the calculating melasma area severity index (MASI) score. Quality of Life (QOL) was assessed using MELASQOL scale with a standard structured questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis:

Descriptive, Chi-square test and contingency coefficient analysis.

Results:

In 140 cases of melasma, 95 (67.9%) were females and 45 (32%) were males. Common age group affected was 31-40 years (65%). Majority were unskilled workers with average sun exposure of more than 4 hours (44%). Family history was observed in 18% cases. Malar type (68%) was the most common pattern observed. Mean MASI score was 5.7. WLE showed dermal type in 69% cases. Common findings on dermoscopy were reticular pigment network with perifollicular sparing and color varying from light to dark brown. Mean MELASQOL score was 28.28, with most patients reporting embarrassment and frustration.

Conclusions:

This study showed that melasma has a significant negative effect on QOL because though asymptomatic it is disfiguring affecting self-esteem. Dermoscopic examination did not help in differentiating the type of melasma.

Keywords: Dermoscopy, melasma, QOL, Wood's lamp

What was known?

Melasma is one of the most common pigmentary disorder predominantly seen in females.

Introduction

My skin is black upon me; and my bones are burned with heat – (Job 30:30).

Since the beginning of human kind, the concept of beauty played a vital role in the existence. The ancient Greeks first described the gospel of beauty.[1]

Human skin color varies from almost black to yellowish pink depending on the density of melanin in the skin. Monotonous skin color is the essence of a vibrant skin. Any mottling in the skin tone had a negative connotation among different cultures. It is an aesthetically displeasing entity. The quotation given above shows the extent of mental trauma; this pigmentary change can cause to the patient.[2] In a survey of 2000 black patients seeking dermatologic care in private practice, the third most commonly cited skin disorders was pigmentary problem, of which post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, vitiligo were diagnosed most often.[3]

Though clinico-epidemiological profile of melasma in India has been extensively studied, there is paucity of data on effect on quality of life. Thus, this study is undertaken to study the clinico-epidemiological pattern, dermascopy, Wood's lamp findings and the quality of life in patients with melasma.

Materials and Methods

A hospital-based, descriptive study was conducted from October 2012 to June 2014 at JSS Hospital, Mysore.

The study population includes all melasma patients attending out-patient department of dermatology, J.S.S. Hospital, Mysore. An informed consent was taken from all subjects and recorded on a standard proforma. The study was approved by the ethical committee of JSS Hospital.

All the patients clinically diagnosed as melasma were attending the out-patient department of dermatology. Patients who are on treatment with depigmenting agents and topical steroids for past 1 month. Patients who have undergone procedures like micro dermabrasion, chemical peeling and lasers were excluded.

MASI score: Severity of melasma was assessed by calculating the MASI score.

The severity of the melasma in each of the four regions (forehead, right malar region, left malar region and chin) is assessed based on three variables: Percentage of the total area involved (A), darkness (D), and homogeneity (H).

To calculate MASI score, the sum of severity grade for darkness (D) and homogeneity (H) is multiplied by the numerical values of the areas (A) involved and by the percentages of the four facial areas.

Total MASI score: Forehead 0.3 (D+H) A + right malar 0.3 – (D+H) A + left malar 0.3 (D+H) A + chin 0.1(D+H) A.

QOL

Quality of life was assessed using MELASQOL score with a standard structured questionnaire of 10 questions.

Investigations:

Wood's lamp examination

Dermascopy.

Results

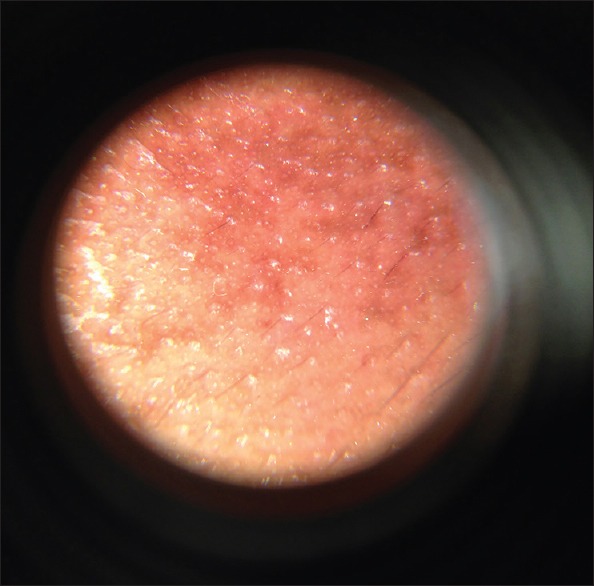

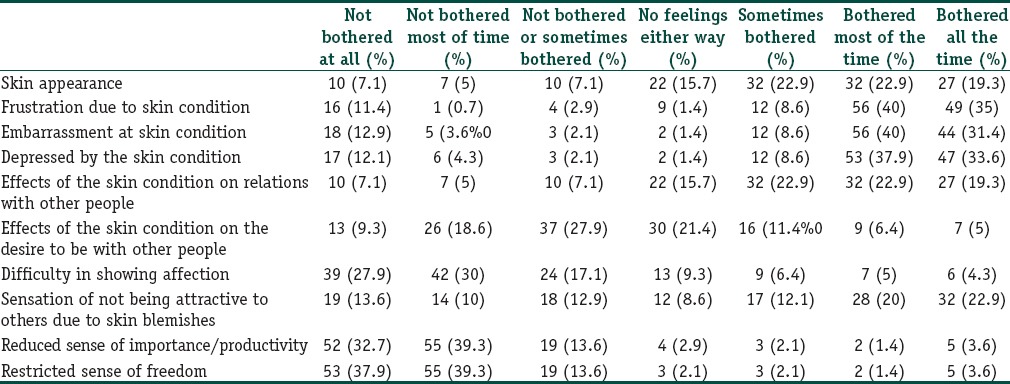

In total of 140 cases, 95 (67%) were females and 45 (32%) were males. Majority was in the age group of 31–40 years in both males and females (42% and 55%, respectively) [Table 1]. The youngest age in our study was 20 years and eldest was 68 years. The mean age of onset was 37.13 years. Melasma was most commonly observed in agriculturists (65%, P < 0.005) followed by skilled workers (31%). 94 (67.1%) patients had melasma for duration above 6 months. (P = 0.001). Twenty-seven (19.3%) had for 3–6 months followed by less than 3 months in 19 patients (13.6%). Twenty-five patients (18%) showed positive family history. Sixty-two patients (44.3%) had a sun exposure of more than 4 hours (P = 0.008). History of drug intake prior to the onset of melasma was there in nine (6.4%) patients out of which four patients were on OCPs. Menstrual cycles were regular in 77 (81%) patients and irregular in 12 (12.6%) [Figure 1]. Malar pattern was seen in 95 (67.9%) patients (P = 0.001) followed by centro-facial in 35 patients (25%) [Figures 2 and 3]. The mean score observed was 5.7, minimum was 0.9 and maximum was 28 [Table 2]. Total of 97 (69.3%) patients showed dermal type, 25 (17.9%) epidermal type and 18 (12.9%) patients mixed type on Wood's lamp examination. Dermoscopic examination was done in 101 patients. A reticulate pattern was observed in 95% cases, which was patchy in 62.4% cases [Figure 4]. Perifollicular sparing is seen in 97% cases [Figure 5]. The color varied from light brown to dark brown [Figure 6]. The effect on quality of life was highly significant and it was more in homemakers and skilled workers. Common problems reported were frustration, embarrassment and depression due to melasma. 40% of the patients were bothered most of the time and 35% were bothered all the time. The effect on sense of freedom and importance was less than 4% [Table 3].

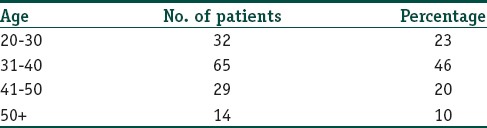

Table 1.

Age distribution and melasma

Figure 1.

Malar type

Figure 2.

Diffuse type

Figure 3.

Centro-facial type

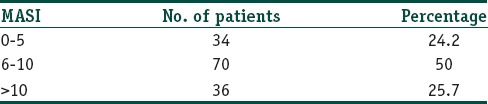

Table 2.

MASI score grading

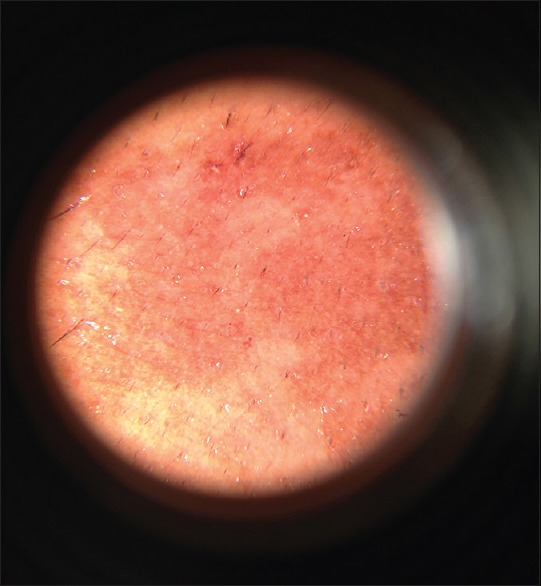

Figure 4.

Dermoscopy - patchy pattern

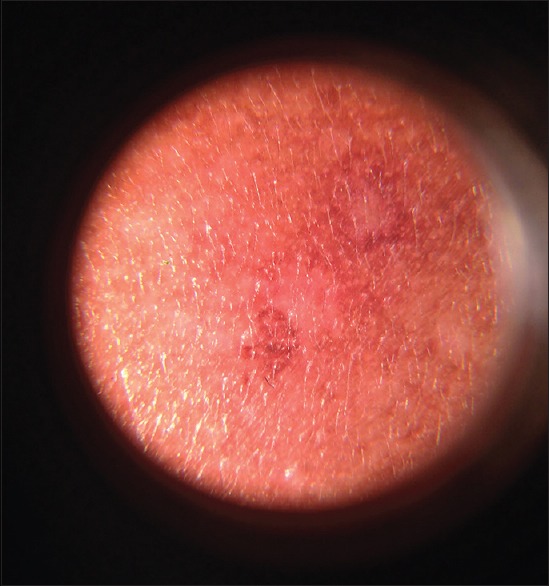

Figure 5.

Dermoscopy - perifollicular sparing

Figure 6.

Dermoscopy - light brown color

Table 3.

Quality of life questionnaire results

Discussion

Melasma occurs in middle-aged adults and is more commonly seen in females. The mean age of onset was 37.13 years. This was similar to the study by Achar and Rathi where the mean age of patients with melasma was 33.45 years.[4] In our study group, majority of patients were in the age group of 31–40 years (46.4%). This was similar to study by Krupa Shankar et al.[5] On the contrary, Kalla et al. in their study observed that melasma was common among younger age group contributing about 87% in the age group of 20–40 years. This shows that melasma is more common in the third decade of life.[6]

Among the study population, females (67.9%) contributed to a wider scale of proportion than the males and the male to female ratio was 1:2.5. This coincides with other studies done by Sanchez et al.[7] A study done by Sarkar et al. illustrated a prevalence of 26% among Indian males.[8] Thus, a female preponderance was observed in all these studies. This can be attributed to hormonal factors. Johnston et al. in their study pointed out that the depth of pigmentation may fluctuate in synchrony with the menstrual cycle. Women are likely to be more conscious and apprehensive about their skin condition and it may also contribute enhanced percent of females seeking for medical attention among different studies.[9]

Majority (67%) suffered from melasma for duration greater than 6 months, this is consistent with the study conducted by Kalla et al.[6]

Agricultural laborers (46.4%) formed the major part among the study group, which may attribute to maximum sun exposure, which is one of the major etiological factors of melasma.

Sun exposure was present among all our patients in the study group. Majority (44%) had duration of exposure greater than 4 hours. This was similar to other studies explaining the fact that UV radiation stimulates melanogenesis, thereby playing a significant role in the etiology of melasma.[10]

A positive family history was seen in 17.9% of the patients, whereas it was seen in 61% cases in study by Handel et al., which proved that genetic influence might play a role in the etiology of melasma.[11] Our study did not show any significant role of prior drug intake as an etiological factor.

Majority of the study group (68%) had a malar pattern of melasma. This was followed by centro-facial (25%) and mandibular (7.1%). Tamega Ade et al. reported that the zygomatic area was the most commonly affected site in Brazilian woman.[12]

Most of the patients (50%) had a MASI score of range 5–10. Pandya et al. stated that MASI has face validity, as it attempts to measure the size and darkness of pigmentation associated with melasma, which are the most frequent symptoms of patients with this disorder.[13]

Wood's lamp examination showed dermal type (69%) to be more common followed by epidermal (18%) and mixed (12%). This was similar to studies by Ponzio et al. This may suggest that melasma is resistant to treatment because of involvement of deeper layers of skin.[14]

Dermoscopic examination in our study subjects showed a reticulate pattern in 95% cases. Pigmentation was diffuse in 37.6% cases and patchy in 62.4%. Color varied from light to dark brown. Perifollicular sparing was seen in almost all cases (97%), which were similar to findings described by Mahajan.[15] In our study dermoscopy did not help in classifying melasma as epidermal, dermal depending on the color of pigment as observed by Barcaui et al.[16]

Melasma has a significant negative impact on quality of life. In this study majority of the patients were depressed, frustrated and embarrassed about their skin condition. Higher MELSQOL scores were observed irrespective of MASI score indicating that severe facial blemishes of any cause affect the self-perception of individual. Various studies on quality of life using MELASQOL showed similar results.[17,18,19,20]

What is new?

Melasma has a significant negative impact on quality of life. Dermoscopic examination did not help in classifying the type of melasma.

Footnotes

Source of support: None declared.

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Rhodes G. The evolutionary psychology of facial beauty. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:199–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thappa DM. Melasma (chloasma): A review with current treatment options. Indian J Dermatol. 2004;49:165–76. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halder RM, Grimes PE, McLaurin CI, Kress MA, Kenney JA., Jr Incidence of common dermatoses in a predominantly black dermatologic practice. Cutis. 1983;32:388–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: A clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krupa Shankar DS, Somani VK, Kohli M, Sharad J, Ganjoo A, Kandhari SA, et al. Cross-sectional, multicentric clinico-epidemiological study of melasma in India. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2014;4:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s13555-014-0046-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalla G, Anush G, Kachhawa D. Chemical peeling- Glycolic acid versus trichloroacetic acid in melasma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2001;67:82–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez MR. Cutaneous diseases in Latinos. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:689–97. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar R, Jain RK, Puri P. Melasma in Indian Males. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston GA, Sviland L, McLelland J. Melasma of the arms associated with hormone replacement therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1988;139:932. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu IB, Lambert C, Lotti TM, Hercogová J, Sintim-Damoa A, Schwartz RA. Melasma. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2012;147:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, Miot LD, Miot HA. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: A case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:588–94. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamega Ade A, Miot LD, Bonfietti C, Gige TC, Marques ME, Miot HA. Clinical patterns and epidemiological characteristics of facial melasma in Brazilian women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:151–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandya AG, Hynan LS, Bhore R, Riley FC, Guevara IL, Grimes P, et al. Reliability assessment and validation of the Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) and a new modified MASI scoring method. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponzio HA, Cruz M. Acurácia do exame sob a lâmpada de Wood na classificação dos cloasmas. An Bras Dermatol. 1993;68:325–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahajan SA. Melasma. In: Khopkar US, editor. Dermoscopy and trichoscopy in diseases of the brown skin-atlas and short text. 1st ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Med Publishers; 2012. pp. 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barcauí CB, Pereira FBC, Tamler C, Fonseca RMR. Classification of melasma by dermoscopy: Comparative study with Wood's lamp. Surg Cosm Dermatol. 2009;1:115–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dominguez AR, Balkrishnan R, Ellzey AR, Pandya AG. Melasma in Latina patients: Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of a quality-of-life questionnaire in Spanish language. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cestari TF, Hexsel D, Viegas ML, Azulay L, Hassun K, Almeida AR, et al. Validation of a melasma quality of life questionnaire for Brazilian Portuguese language: The MelasQoL-BP study and improvement of QoL of melasma patients after triple combination therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156:13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misery L, Schmitt AM, Boussetta S, Rahhali N, Taieb C. Melasma: Measure of the impact on quality of life using the French version of MELASQOL after cross-cultural adaptation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:331–2. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dogramaci AC, Havlucu DY, Inandi T, Balkrishnan R. Validation of a melasma quality of life questionnaire for the Turkish language: The MelasQoL-TR study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:95–9. doi: 10.1080/09546630802287553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]