Abstract

Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a rare autosomal recessive disease, characterized by partial oculocutaneous albinism, frequent pyogenic infections, and the presence of abnormal large granules in leukocytes and other granulecontaining cells. The abnormal granules are readily seen in blood and marrow granulocytes. Other clinical features include silvery hair, photophobia, nystagmus and hepatosplenomegaly. However, the presence of abnormal giant intracytoplasmic granules in neutrophils and their precursors are diagnostic of CHS. Here, we present a series of five cases, out of which four presented in the accelerated phase. In all the five cases, the giant granules were noted predominantly in the cytoplasm of lymphocytes, which is a rare occurrence compared to those present in the granulocytes.

Keywords: Albinism, autosomal recessive disease, Chediak-Higashi syndrome, photophobia

What was known?

CHS is a part of silvery gray hair syndromes with presence of giant cytoplasmic granules predominantly in the cytoplasm of granulocytes in the peripheral smear.

Introduction

Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a rare, autosomal recessive multi-system disorder characterized by hypopigmentation of the skin, eyes and hair, prolonged bleeding time, easy bruisability, recurrent infection, abnormal NK cell function and peripheral neuropathy. The presence of giant peroxidase-positive lysosomal-like organelles most readily seen in blood and marrow leukocytes is diagnostic. Herein, we present five cases of CHS, out of which four presented to us in accelerated phase and exhibited large granules predominantly in the cytoplasm of lymphocytes.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 5-year-old boy child, born out of a first-degree consanguineous marriage, presented with the history of fever, bilateral neck swellings and loss of appetite. On examination, pallor, silvery gray hair, oculocutaneous albinism was observed. Generalized lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly were also noted. Subsequently, a complete blood count showed a hemoglobin count of 8.6 g/dL, total WBC count of 22.1 × 103/uL, with lymphocytes showing single large round to oval purple-colored intracytoplasmic granules.

Case 2

A 3-year-old female child [Figure 1], born out of a third-degree consanguineous marriage, presented with history of recurrent multiple furunculosis over all the limbs. Cervical, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes were enlarged with moderate hepatosplenomegaly. Generalized hypopigmentation was noted all over the body. The ophthalmologic examination revealed horizontal nystagmus with hypo pigmentation of fundus. Peripheral smear and the bone marrow aspirate showed similar giant granules in the lymphocytes. Also, the neutrophilic and eosinophilic granules were larger in size with phagocytic vacuoles in the monocytes. A skin biopsy showed lack of melanin pigment in the basal layer of epidermis.

Figure 1.

A 3 year-old-female child with oculocutaneous albinism and gray hair

Case 3

A 2-year-old female child [Figure 2], born out of a consanguineously married couple, presented with the history of gray hair, hypopigmented patches over the face and the limbs. Interestingly, the mother had noticed avoidance of the bright light by the child. The ophthalmologic examination revealed a pale fundus. Moderate hepatosplenomegaly was noted on abdominal examination. The complete blood count showed low hemoglobin and low platelet count with lymphocytic predominance. The peripheral smear examination revealed giant block granules in the cytoplasm of the lymphocytes [Figure 3]. Fine-needle aspiration of the lymph node [Figure 4] revealed similar intracytoplasmic granules in the lymphoid cells. The bone marrow examination showed giant eosinophilic granules [Figure 5] and giant solitary block granules in the cytoplasm of lymphoid cells. A skin biopsy was performed in this case, which again showed lack of melanin pigment in the epidermis.

Figure 2.

A 2 year-old-female child with oculocutaneous albinism and gray hair

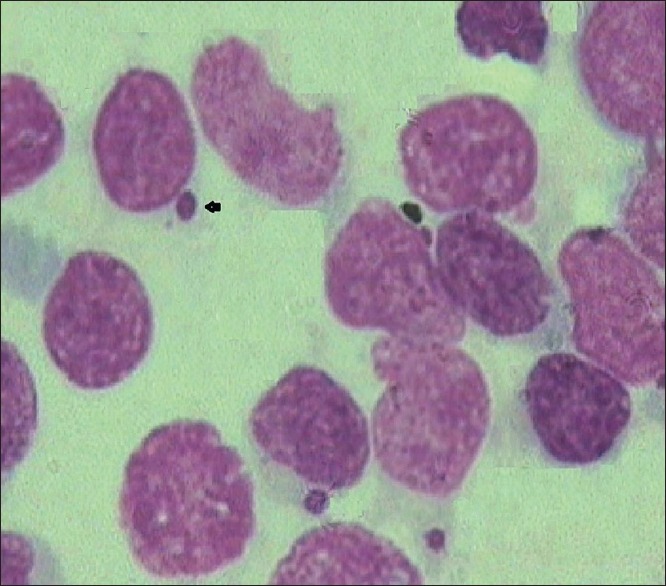

Figure 3.

Peripheral smear showing cytoplasmic inclusion (arrow) in the lymphocyte (×10 ×100 – Wrights stain)

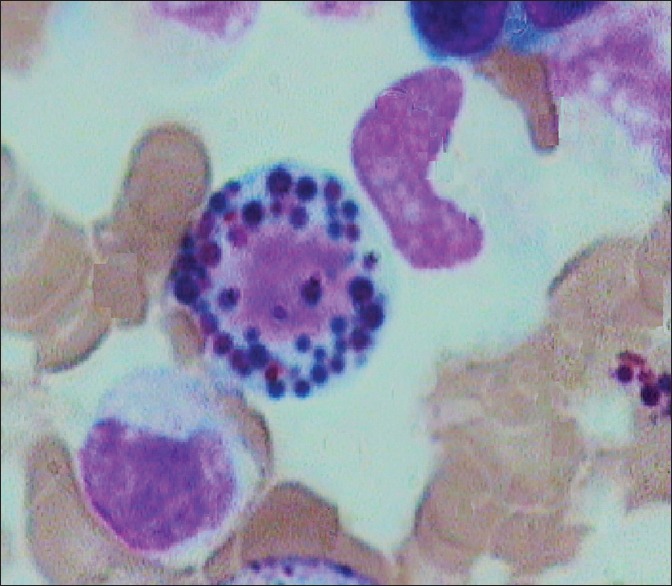

Figure 4.

FNAC showing solitary block granule (arrow) in the lymphocyte (×10 ×100 – Wrights stain)

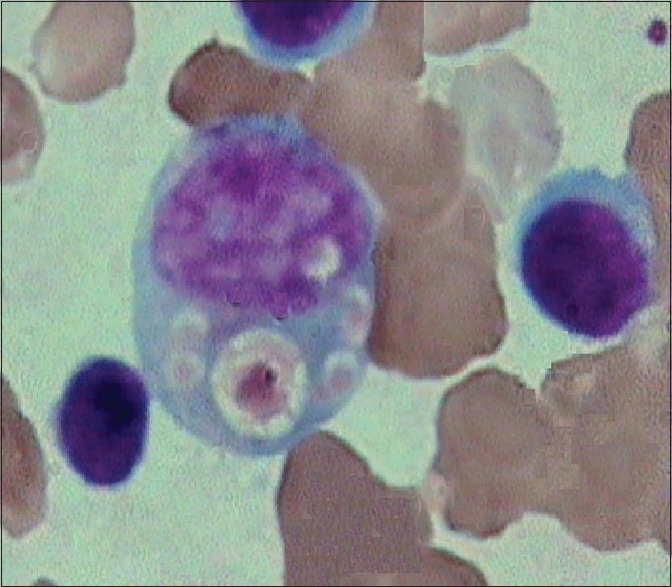

Figure 5.

Bone marrow aspirate showing giant eosinophilic granules (×10 ×100 – Wrights stain)

Case 4

A 5-month-old infant, presented with history of recurrent respiratory tract infection. Gray-colored hair was noted with shiny and blond skin. Mild hepatomegaly was noted; however, no lymph nodes were palpable. Complete blood count was within normal limits. However, the peripheral smear examination revealed solitary block granules in the cytoplasm of some of the lymphocytes. The bone marrow aspirate showed similar inclusions in the lymphoid cells with giant cytoplasmic granules in the myeloid series cells [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Bone marrow aspirate showing phagocytic vacuole in the myeloid series cell (×10 ×100 – Wrights stain)

Case 5

A 3-year-old male child was referred to our institute with history of failure to thrive. Clinical examination showed silvery gray hair with partial cutaneous albinism; however, organomegaly or lymphadenopathy was absent. Complete blood count was done which showed, low hemoglobin with normal total white blood cell count and low platelet count. In this case also, a careful peripheral examination was the key to diagnosis, which revealed block like inclusions in the lymphocytes. Bone marrow examination also showed similar inclusions in the lymphocytes with giant eosinophilic granules.

Discussion

The Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) was first described by Bequez-cesar in 1943. Chediak, a Cuban hematologist in 1952 and in 1954 Higashi, a Japanese pediatrician found mal-distribution of myeloperoxidase in neutrophilic granules of the affected patients.[1] CHS is caused by mutations in a single gene characterized in 1996 as the LYST gene (lysozyme trafficking regulator) localized to 1q42–43.[2] LYST is a large gene with 55 exons. The 13.5-kb gene transcript produces a protein of 3801 amino acids with a molecular weight of 430 kd. To date, 40 mutations have been identified throughout the gene. These include missense and nonsense mutations, and small deletions and insertions in the coding region.[3]

CHS is a disease of infancy and early childhood. Less than 500 cases have been reported worldwide.[4] There are only few case reports from India.[5,6,7] The pathologic hallmark of CHS is the presence of massive lysosomal inclusion in the leukocytes, fibroblasts and melanocytes, formed through a combined process of fusion, cytoplasmic injury and phagocytosis due to microtubular defect. Recent studies show that lysosomal exocytosis triggered by membrane wounding is defective in CHS.[2]

Most striking abnormality in our cases was solitary giant cytoplasmic inclusion which was noted predominantly in lymphocytes which is a rare occurrence. According to the literature review, such abnormality is predominantly found in the myeloid series cells and less commonly in the lymphocytes. At this juncture, we would like to highlight the importance of careful peripheral smear examination in a child with oculocutaneous albinism, as two children were referred with a clinical diagnosis of lymphoma and one as hemolytic anemia.

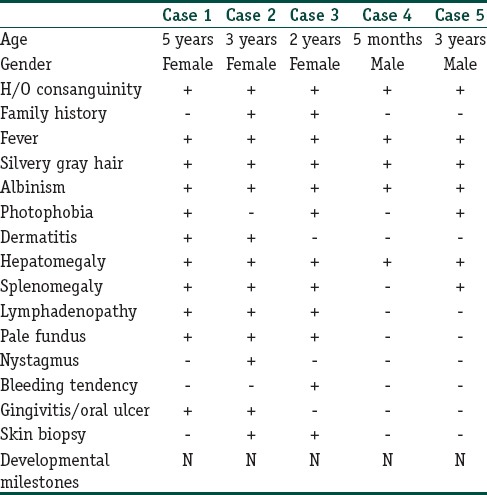

A majority (85%) of patients with CHS develop an accelerated phase of the disease characterized by fever, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, pancytopenia, coagulopathy, neurological abnormalities[8] and diffuse mononuclear cell infiltrates into the organs. Originally thought to be a malignancy resembling lymphoma, the accelerated phase is now known to be hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis characterized by multiorgan inflammation.[9] Here, out of five cases, four [Cases 1, 2, 3 and 5] presented in the accelerated phase. Two out of five children [Cases 1 and 3] succumbed to the infection and the other three children were lost to follow-up. The clinicohematological parameters of all the cases has been illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Illustration of clinicohematological parameters of all the cases

Differential diagnosis of CHS includes other genetic forms of oculocutaneous albinism like Griscelli syndrome and Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome, but both these syndromes lack the characteristic giant granules in neutrophils, which is the hallmark of CHS. Acute and chronic myeloid leukemia may show giant granules resembling those seen in CHS, also referred to as Pseudo-Chediak–Higashi anomaly.[10]

Allogeneic bone marrow transplant has been proposed as the only possibly curative treatment, when done early, before the onset of the accelerated phase.[11,12] Once the accelerated phase occurs, the syndrome is fatal within 30 months. This emphasizes the need for early identification of the disease by careful examination of the peripheral smear by an experienced hematopathologist, so that bone marrow transplantation can be suggested at the earliest.

What is new?

In all our cases such inclusions were found in the cytoplasm of lymphocytes and four out of five cases presented to us in accelerated phase. Hence, emphasis should be on careful peripheral smear examination in a child presenting with silvery gray hair.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Blume RS, Wolff SM. The Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Studies in 4 patients and review of literature. Medicine. 1972;51:247–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrat FJ, Auloge L, Pastural E, Lagelouse RD, Vilmer E, Cant AJ, et al. Genetic and physical mapping of the CHS on chromosome. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:625–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendy JI, Wendy W, Gretchen AG, David A. Gene Reviews [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2014. Chidiak-Higashi Syndrome. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Terkait N, Sadek SA, Al-khaledi D. Chediak–Higashi syndrome: Report of a case with an accelerated phase and review of literature Nada Al Terkait, Sherif A Sadek. Duaa Al-khaledi Kuwait Med J. 2009;41:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasha TS, Vani S, Vasanth A, Augustus M, Ramamohan Y, Das S, et al. Chediak-Higashi syndrome – A case report with ultrastructure and cytogenetic studies. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1997;40:75–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seth P, Bhargava M, Kalra V. Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 1982;19:950–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prakash C, Suvarna N, Rajalakshmi PC, Aravindan KP, Chandrasekharan KG. A case of Chediak-Higashi syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990;38:505–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skubitz KM. Qualitative disorders of leucocytes. In: Lee GR, Foerster J, Lukens J, Paraskevas F, Greer JP, Rodgers GM, editors. Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 1548–64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eapen M, DeLoat CA, Baker KS, Cairo MS, Cowan MJ, Kurtzberg J, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:411–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanjanapongkul S. Chediak–Higashi syndrome: Report of a case with uncommon presentation and review literature. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89:541–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Sheyyab M, Daoud AS, El-Shanti H. Chediak-Higashi syndrome: A report of eight cases from three families. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farhoudi A, Chavoshzadeh Z, Pourpak Z, Izadyar M, Gharagozlou M, Movahedi M, et al. Report of six cases of Chediak–Higashi Syndrome with regard to clinical and laboratory findings. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;2:189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]