Abstract

Development of new therapeutics against Select Agents such as Francisella is critical preparation in the event of bioterrorism. Testing FDA-approved drugs for this purpose may yield new activities unrelated to their intended purpose and may hasten the discovery of new therapeutics. A library of 420 FDA-approved drugs was screened for antibiofilm activity against a model organism for human tularemia, Francisella (F.) novicida, excluding drugs that significantly inhibited growth. The initial screen was based on the 2-component system (TCS) dependent biofilm effect, thus, the QseC dependence of maprotiline anti-biofilm action was demonstrated. By comparing their FDA-approved uses, chemical structures, and other properties of active drugs, toremifene and polycyclic antidepressants maprotiline and chlorpromazine were identified as being highly active against F. novicida biofilm formation. Further down-selection excluded toremifene for its membrane active activity and chlorpromazine for its high antimicrobial activity. The mode of action of maprotiline against F. novicida was sought. It was demonstrated that maprotiline was able to significantly down-regulate the expression of the virulence factor IglC, encoded on the Francisella Pathogenicity Island (FPI), suggesting that maprotiline is exerting an effect on bacterial virulence. Further studies showed that maprotiline significantly rescued F. novicida infected wax worm larvae. In vivo studies demonstrated that maprotiline treatment could prolong time to disease onset and survival in F. novicida infected mice. These results suggest that an FDA-approved drug such as maprotiline has the potential to combat Francisella infection as an antivirulence agent, and may have utility in combination with antibiotics.

Keywords: anti-virulence, biofilm, chlorpromazine, FDA approved, Francisella, Galleria mellonella infection model, maprotiline, mouse model, QseC, sensor histidine kinase, toremifene, two-component system

Introduction

There has been a recent push to determine if FDA-approved drugs can yield activities unrelated to their intended purpose that may hasten the discovery of new therapeutics against select agents,1 such as Francisella (F.) tularensis. Screening libraries of FDA-approved drugs may allow researchers to identify previously unknown targets in these pathogens.2 Bacteria of the genus Francisella are gram-negative coccobacilli, the most notable being the highly virulent F. tularensis. Here, a closely related organism, F. novicida, is used to model the virulent select agent F. tularensis.3

Current and emerging antibiotic resistance represents a crisis on a global scale.4 The recent detection of Francisella's antibiotic resistance,5 and reports relating to the potential emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance6-8 in Francisella species, underscores the urgent need for new antibiotics, or different antimicrobial strategies.9 There are numerous examples of successful drug repurposing.1,2,20 Repurposing already-approved drugs for new indications is currently of much interest, as these compounds already have passed safety tests and are available to physicians for prescription. Recently, FDA-approved drug libraries have been screened for potential inhibitors of both bacterial and viral infectious diseases.1,21,22 A recently published screen that included F. tularensis revealed no new antibiotics that could be used against this organism.2 Our approach is to identify compounds that will target expression of a virulence factor rather than target bacterial growth in our screening strategy, to avoid selecting compounds that may impose strong negative selective pressure on the bacteria and potentially retain activity against antibiotic resistant organisms.

One potential virulence target in Francisella is 2-component systems (TCSs), the bacterial signal transduction pathways. F. novicida has 2 intact TCS annotated as KdpED and FTN1452/1453, plus one orphan sensor kinase (FTN1617, QseC) and one orphan response regulator (FTN1465, PmrA/QseB). Other strains of Francisella, including the fully virulent F. tularensis Schu S4, also have QseC and PmrA/QseB, KdpD, and FTT1543. The sensor kinase QseC in Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and F. tularensis is a known protein target/receptor of the small molecule LED209.10,11 In F. tularensis SchuS4, QseC (FTT_0094c) was found to be a virulence factor and to be a target of LED209, a compound that can rescue mice from tularemia infection.10,12 This molecule serves as an example of a TCS-targeting small-molecule that could be useful for further development as a new therapeutic; however, LED209 is not FDA approved. In F. novicida, QseC was found to be involved in biofilm formation.13 The response regulator PmrA/QseB has been identified as a potential virulence factor in F. novicida and F. tularensis LVS,14-16 and is known to control biofilm formation in F. novicida.13 Thus, measuring biofilm formation (and then demonstrating sensor kinase dependence) represents a useful phenotypic screen for compounds that may also inhibit Francisella virulence through their effect on TCSs.

Virulence in Francisella is regulated by the expression of genes in the Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI), especially iglC.17 A complex including MglA and PmrA/QseB regulates the expression of these genes.18 Following phosphorylation by an upstream sensor kinase, activation of PmrA/QseB leads to an increase in virulence gene expression of the FPI, including iglC expression.19 Compounds that block the activation of the sensor kinase that activates PmrA/QseB may also reduce both biofilm formation and virulence; however, there is no published connection between biofilm formation and virulence in Francisella.

In this study, we screened a library of 420 FDA-approved drugs for their antibiofilm activity against F. novicida. Using a phenotypic screen for biofilm formation as an indication of an effect on the TCS, and eliminating compounds that were significantly directly killing the bacteria (50% cutoff) we identified compounds that were potent antibiofilm agents. We investigated the library through cheminfomatics analysis of their structure vs. their antibiofilm activity. The effect of these compounds was then shown to be dependent on the sensor kinase QseC. We then studied the effect of these compounds on the TCS-dependent expression of virulence through the expression of IglC. Finally, using 2 infection models (G. mellonella and mouse), maprotiline was found to prolong the survival of mice infected with Francisella novicida, suggesting that this FDA-approved drug has the potential to be an anti-virulence compound that could potentially be used to treat Francisella infection in combination with antibiotics.

Results

Screen a FDA-approved drug library

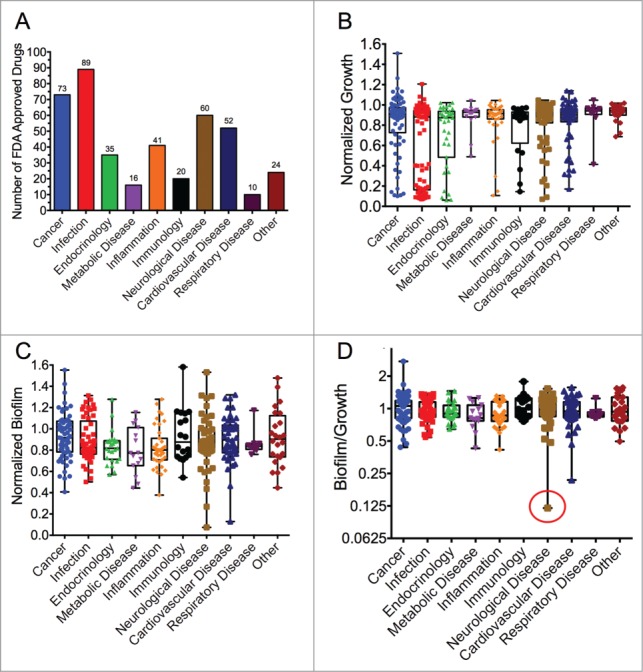

In order to identify FDA-approved drugs that could be repurposed as anti-Francisella compounds, we screened a library of 420 FDA-approved compounds to find drugs with a new feature: antibiofilm properties. Our hypothesis was that inhibition of TCS-regulated biofilm formation might also indicate inhibition of other TCS-regulated properties of Francisella, including virulence. There is no direct evidence that biofilm formation is a virulence factor in Francisella; however, biofilm inhibition is a phenotype that could be usefully and readily screened. The categorization of all the drugs in the library is described graphically in Fig. 1A (also see Table S1). Over half of the drugs are classified in 3 largest categories: “cancer” (73 compounds), “infection” (89 compounds), and “neurological disease” (60 compounds) according to the manufacturer.

Figure 1.

FDA-approved drug library screen results. (A) Categorization of the 420 compounds in the FDA-approved drug library used in the study. Box plots showing the effect of the drugs in the library on (B) F. novicida growth, (C) biofilm formation, and (D) the ratio of biofilm to growth (Biofilm/Growth) in log2. The data are normalized to wells treated with 1% DMSO and no drug. Box plots are shown with bars extending from min to max, mid-point indicates the median, and all data points are overlaid. The red circle in D indicates maprotiline.

In previous studies we have identified compounds with antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity (especially antimicrobial peptides) against Francisella using growth inhibition and crystal violet staining methods.23–26 Using these techniques to develop a phenotypic screen, we identified compounds from the FDA-approved drug library that exerted antibiofilm (but not antimicrobial) activity against F. novicida. More clearly, we defined antibiofilm activity as inhibition of bacterial biofilm formation to a significantly greater amount than inhibition of bacterial growth (cutoff of 50% for growth inhibition). As an example, levofloxacin inhibited both growth and biofilm by equal amounts (∼90%, Table S1), thus its antibiofilm effect can be entirely attributed to its growth inhibition, and so it does not meet the criteria. Maprotiline for example inhibited F. novicida growth only 47% but inhibited biofilm formation by 93%, thus meeting the criteria for an antibiofilm compound.

Many compounds in the library were found to be antimicrobial, such as previously known antibiotics. The growth inhibitory compounds identified in the screen can be seen in Figure 1B. The bimodal distribution of the effectiveness of drugs within the “infection” category is striking, with antibiotics of known effectiveness27 such as levofloxacin having 92% growth inhibition at 100 µM. Other “infection” category drugs, such as daptomycin, had no significant effect on F. novicida growth, in agreement with published results.28 Not surprisingly, of the top 10 most antimicrobial compounds identified during this screen, 60% (6/10) are previously known antibiotics. Since the activity of these antibiotic compounds is not novel against Francisella, these compounds were not studied further.

Outside of the “infection” category, several other groups of drugs had a few compounds with a significant inhibitory effect on growth (Fig. 1B). Notably, the categories cancer, endocrinology, neurological disease, and inflammation also contained a few compounds that resulted in >90% growth inhibition. Interestingly, one “cancer” compound significantly promoted F. novicida growth in vitro mitoxantrone HCl, a Type II topoisomerase inhibitor. However, we were more interested to pursue the potential antibiofilm activities of compounds, which for specificity reasons requires that compounds do not significantly inhibit or promote growth.

Using the crystal violet staining method, we screened all 420 compounds for their effect on F. novicida biofilm formation. To present a clearer picture of the antibiofilm effect, we graphed both the net effect on biofilm inhibition (Fig. 1C) (which does not account for any growth inhibition) and biofilm inhibition as a ratio accounting for the effect on growth (biofilm:growth ratio, Fig. 1D). When assayed for biofilm inhibition (not accounting for growth), each of the categories contained some drugs that led to either a significant increase or decrease in the total amount of biofilm produced by Francisella (Fig. 1C), likely due to their effects on growth. The categories “cardiovascular disease” and “neurological disease” contained a few drugs with >90% biofilm inhibition, relative to the 1% DMSO control. For example, the drug eltrombopag (in the category cardiovascular disease) was found to inhibit biofilm significantly, with a biofilm:growth ratio of 0.22. The neurological drug fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor also inhibited biofilm formation significantly. Interestingly, a few compounds significantly promoted biofilm formation, such as lapatinib in the category “immunology” and fulvestrant in the “cancer” category.

The biofilm:growth ratio was used to correct for the effect of compounds that strongly affected growth and do not appear to have a distinct or separate effect on biofilm. As stated above, levofloxacin inhibited both the measured growth and biofilm by 92%, thus we attribute its “biofilm effect” entirely to the growth inhibition effect of the compound. The results of the analysis using the biofilm:growth ratio shows that one drug in each of the “neurological disease” and “cardiovascular disease” categories are greatly inhibitory to Francisella biofilm formation, with a relatively small effect on growth (Fig. 1D). Table S1 lists all of the biofilm:growth ratios from each compound in the screen. Maprotiline (see structure in Figure S4) was the most inhibitory of the biofilm:growth ratio (0.12) while not inhibiting bacterial growth more than 50%, and was thus chosen for further study.

The top-10 and bottom-10 drugs (with greatest positive and negative effect) from each of the analyses are presented in Table 1 (as Tables 1A - growth, 1B - biofilm and 1C - biofilm:growth). Interestingly, 2 antibiotics, Cefdinir and Aztreonam, were found to result in a low biofilm:growth ratio. Cefdinir, a bactericidal cephalosporin antibiotic highly active against Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species,29 with a biofilm:growth ratio of 0.16, was found to strongly inhibit F. novicida biofilm formation (fold15-) while inhibiting growth by only fold2-. Cephalosporins are not known to be very active against Francisella strains,30 so this finding was interesting for possible further study. In addition, a second antibiotic, aztreonam, a synthetic monocyclic β-lactam antibiotic, also impacted the F. novicida biofilm:growth ratio to 0.25, decreasing biofilm formation by fold10-. F. novicida is generally considered resistant to the antibacterial effect of β-lactams, as are all members of the genus Francisella,31 so this finding was significant. A “cardiovascular disease” compound, Doxazosin mesylate, strongly increased the biofilm:growth ratio, and although very antibacterial, caused a large increase in biofilm formation of the remaining bacteria (almost to untreated levels) (Table 1C). The performance of some the different classes of compounds is discussed in more detail below.

Table 1.

Top 10 pro- and anti-microbial and biofilm drugs from our screen.

A:

Growth

| Drug | Growth | Description | Category | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMG-073 HCl (Cinacalcet) | 0.06 | Calcium mimic | Endocrinology | 331 |

| Nebivolol (Bystolic) | 0.07 | β1 receptor blocker | Endocrinology | 352 |

| Nitazoxanide (Alinia, Annita) | 0.07 | Antiprotozoal agent | Infection | 135 |

| Disulfiram (Antabuse) | 0.07 | Treatment for chronic alcoholism | Neurological Disease | 102 |

| Nitrofurazone (Nitrofural) | 0.07 | Antibiotic | Infection | 41 |

| Levofloxacin (Levaquin) | 0.08 | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic | Infection | 59 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.08 | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic | Infection | 59 |

| Novobiocin sodium (Albamycin) | 0.08 | DNA gyrase inhibitor antibiotic | Infection | 67 |

| Clarithromycin (Biaxin, Klacid) | 0.08 | Macrolide antibiotic | Infection | 122 |

| Fleroxacin (Quinodis) | 0.09 | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic | Infection | 59 |

| Mitoxantrone Hydrochloride | 1.51 | Type II topoisomerase inhibitor | Cancer | 268 |

| Temsirolimus (Torisel) | 1.26 | mTOR inhibitor. | Cancer | 3 |

| Itraconazole (Sporanox) | 1.21 | Antifungal agent | Infection | 366 |

| Lapatinib Ditosylate (Tykerb) | 1.16 | Inhibitor of HER2/EGFR tyrosine kinase | Cancer | 50 |

| Manidipine (Manyper) | 1.14 | Vasoselective dihydropyridine calcium antagonist | Cardiovascular Disease | 267 |

| Rapamycin (Sirolimus) | 1.13 | mTOR inhibitor | Cancer | 3 |

| Erlotinib HCl | 1.13 | Inhibitor of HER1/EGFR tyrosine kinase | Cancer | 52 |

| Imatinib Mesylate | 1.10 | c-kit, PDGF-R and c-ABL inhibitor | Cancer | 137 |

| Ivermectin | 1.08 | Broad-spectrum antiparasitic medication | Infection | 391 |

| Nilotinib (AMN-107) | 1.08 | Inhibitor of BCR-ABL | Cancer | 114 |

B:

Biofilm formation

| Drug | Biofilm | Description | Category | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythromycin (E-Mycin) | 0.05 | Macrolide antibiotic | Infection | 122 |

| Clarithromycin (Biaxin, Klacid) | 0.05 | Macrolide antibiotic | Infection | 122 |

| Disulfiram (Antabuse) | 0.05 | Treatment for chronic alcoholism | Neurological Disease | 102 |

| Lomefloxacin hydrochloride (Maxaquin) | 0.06 | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic | Infection | 59 |

| Progesterone (Prometrium) | 0.06 | Steroid hormone | Endocrinology | 270 |

| Ofloxacin (Floxin) | 0.06 | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent | Infection | 59 |

| Nitazoxanide (Alinia, Annita) | 0.06 | Antiprotozoal agent | Infection | 135 |

| Nitrofurazone (Nitrofural) | 0.06 | Antibiotic | Infection | 41 |

| Cefdinir (Omnicef) | 0.06 | Bacteriocidal antibiotic | Infection | 286 |

| Chlorpromazine (Sonazine) | 0.07 | Dopamine and potassium channel inhibitor | Neurological Disease | 11 |

| Lapatinib Ditosylate (Tykerb) | 1.58 | Inhibitor of HER2/EGFR tyrosine kinase | Cancer | 50 |

| Fulvestrant (Faslodex) | 1.55 | Synthetic estrogen receptor antagonist (SERD) | Cancer | 308 |

| Nefiracetam (Translon) | 1.53 | Cognitive enhancer | Neurological Disease | 182 |

| Niacin (Nicotinic acid) | 1.48 | Water-soluble vitamin part of the vitamin B group | Other | 10 |

| Evista (Raloxifene Hydrochloride) | 1.42 | Selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) | Cancer | 83 |

| Nicotinamide (Niacinamide) | 1.39 | Water-soluble vitamin part of the vitamin B group | Other | 10 |

| Tropisetron | 1.34 | 5-HT3 receptor antagonist | Cancer | 76 |

| Nimodipine (Nimotop) | 1.32 | Calcium channel blocker | Cardiovascular Disease | 54 |

| Gabapentin Hydrochloride | 1.31 | GABA analog | Neurological Disease | 26 |

| Isoniazid (Tubizid) | 1.31 | Anti-tuberculosis pro-drug | Infection | 23 |

C:

Biofilm:Growth Ratio

| Drug | Biofilm/growth | Description | Category | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maprotiline hydrochloride | 0.12 | Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | Neurological Disease | 11 |

| Cefdinir (Omnicef) | 0.16 | Bacteriocidal antibiotic | Infection | 286 |

| Eltrombopag (SB-497115-GR) | 0.22 | Agonist of TpoR | Cardiovascular Disease | 112 |

| Aztreonam (Azactam, Cayston) | 0.25 | Beta-lactam antibiotic | Infection | 339 |

| Chlorpromazine (Sonazine) | 0.33 | Dopamine and potassium channel inhibitor | Neurological Disease | 11 |

| Flurbiprofen (Ansaid) | 0.42 | Phenylalkanoic acid derivative family NSAIDs | Inflammation | 9 |

| Orlistat (Alli, Xenical) | 0.43 | Lipase inhibitor | Metabolic Disease | 357 |

| Temsirolimus (Torisel) | 0.44 | mTOR inhibitor | Cancer | 3 |

| Candesartan cilexetil (Atacand) | 0.47 | Nonpeptide Ang II receptor antagonist | Cardiovascular Disease | 141 |

| Rapamycin (Sirolimus) | 0.47 | mTOR inhibitor | Cancer | 3 |

| Doxazosin mesylate | 4.70 | α−1 adrenergic receptor blocker | Cardiovascular Disease | 185 |

| Toremifene Citrate | 3.57 | Selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) | Endocrinology | 83 |

| Telmisartan (Micardis) | 3.54 | angiotensin II receptor antagonist (ARB) | Cardiovascular Disease | 112 |

| Nisoldipine (Sular) | 3.16 | Calcium channel blocker | Cardiovascular Disease | 54 |

| Abiraterone Acetate (CB7630) | 3.13 | 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase (CYP17A1) inhibitor | Cancer | 304 |

| Ketoconazole | 2.89 | Broad-spectrum antifungal agent | Infection | 366 |

| Terbinafine (Lamisil, Terbinex) | 2.84 | Broad-spectrum antifungal agent | Infection | 80 |

| Evista (Raloxifene Hydrochloride) | 2.74 | Selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) | Cancer | 83 |

| Lansoprazole | 2.64 | EGFR and HER2 autophosphorylation inhibitor | Cancer | 177 |

| Elvitegravir (GS-9137) | 2.51 | HIV integrase inhibitor | Infection | 5 |

In order to meet our criteria of an antibiofilm compound, we eliminated all compounds that inhibited or promoted bacterial growth by more than 50%. Although more stringent criteria could be applied, this 50% cut-off level accommodates variations in growth that may have occurred during the screen and includes a large range of compounds (288) from the library. The revised top-10 and bottom-10 list of compounds that pass the 50% cut-off and still show significant biofilm:growth ratios are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Top 10 highest or bottom 11 compounds and their Biofilm: Growth ratio, excluding compounds that promote or inhibit growth by 50% or more

| Item Name | Growth | Biofilm | Biofilm: Growth Ratio (Normalized to DMSO) | Description | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maprotiline hydrochloride | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.12 | Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | Neurological Disease |

| Eltrombopag (SB-497115-GR) | 0.59 | 0.13 | 0.22 | Agonist of the TpoR | Cardiovascular Disease |

| Flurbiprofen (Ansaid) | 0.91 | 0.38 | 0.42 | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Inflammation |

| Orlistat (Alli, Xenical) | 1.04 | 0.44 | 0.43 | Lipase inhibitor | Metabolic Disease |

| Temsirolimus (Torisel) | 1.26 | 0.55 | 0.44 | mTOR inhibitor | Cancer |

| Candesartan cilexetil (Atacand) | 0.99 | 0.46 | 0.47 | Ang II receptor (ATR) antagonist | Cardiovascular Disease |

| Rapamycin (Sirolimus) | 1.13 | 0.53 | 0.47 | mTOR inhibitor | Cancer |

| Clomipramine hydrochloride (Anafranil) | 0.55 | 0.27 | 0.48 | Norepinephrine Transporter (NET) blocker | Neurological Disease |

| Crystal violet | 0.90 | 0.45 | 0.50 | Triarylmethane dye | Other |

| Nilotinib (AMN-107) | 1.08 | 0.55 | 0.51 | Inhibitor of BCR-ABL | Cancer |

| Fulvestrant (Faslodex) | 1.07 | 1.55 | 1.45 | Synthetic estrogen receptor antagonist (SERD) | Cancer |

| Finasteride | 0.62 | 0.90 | 1.46 | Inhibitor of steroid Type II 5 α reductase | Endocrinology |

| Cilostazol | 0.66 | 0.96 | 1.46 | Treatment for peripheral vascular disease | Cardiovascular Disease |

| Nicotinamide (Niacinamide) | 0.94 | 1.39 | 1.49 | Water soluble B vitamin family | Other |

| Nefiracetam (Translon) | 1.00 | 1.53 | 1.53 | Cognitive enhancer | Neurological Disease |

| Adrucil (Fluorouracil) | 0.69 | 1.06 | 1.54 | Antimetabolite | Other |

| Niacin (Nicotinic acid) | 0.94 | 1.48 | 1.56 | Water soluble B vitamin family | Other |

| Fenofibrate (Tricor, Trilipix) | 0.72 | 1.13 | 1.57 | Fibric acid derivative | Cardiovascular Disease |

| Isotretinoin | 0.71 | 1.18 | 1.67 | Chemotherapy medication | Cancer |

| Betamethasone valerate (Betnovate) | 0.53 | 0.94 | 1.78 | Glucocorticoid steroid | Immunology |

| Evista (Raloxifene Hydrochloride) | 0.52 | 1.42 | 2.74 | Selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) | Cancer |

Cheminformatic analysis of the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity in the screen

The relationship between structure and activity is an essential component of the compound library screening analyses. To analyze this, we performed a broad Spearman rank correlation between moieties present and activity of all the compounds (see Table S1), as well as Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) and hierarchical clustering methods (Fig. 2) to not only compare and organize classes of compounds but to relate these chemical signatures to their activities.

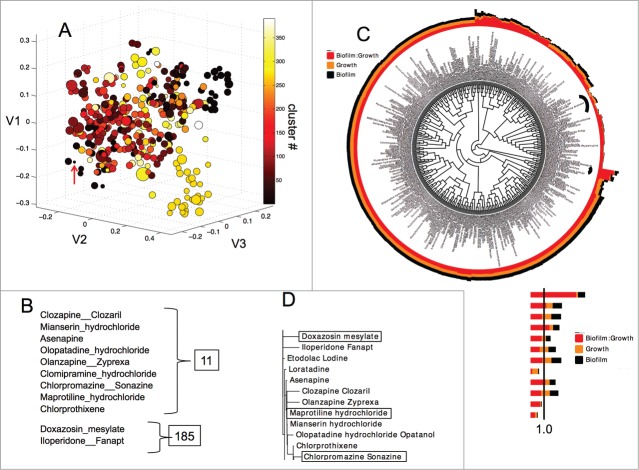

Figure 2.

Structure-activity clustering of the drug library. (A) 3D scatter plot of the FDA-approved drugs in the screen with multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis, where the size of the spheres are proportional to the biofilm:growth ratio values. Clustering is indicated by color (refer to the color bar). V1, V2, V3 are the largest eigenvalues. The red arrow indicates an example drug, maprotiline (cluster 11) with a small biofilm:growth ratio. (B) Identities of drugs within the selected clusters. (C) Circular phylogenetic tree of the same list of compounds as in A with hierarchical clustering. The legend indicates the identities of the colored bars surrounding the tree. Black curved lines inside the circle indicate clusters 11 and 185. (D) Phylogenetic tree of clusters extracted from panel C with doxazosin from cluster 185 and maprotiline and chlorpromazine from cluster 11 selected. The biofilm:growth ratio is shown in red, growth is shown in gold, and biofilm formation is indicated in black.

To investigate the overall correlation between structural moieties of the drugs in the screen and their effect on F. novicida growth and biofilm, we counted the structural moieties of each compound and tallied them for 222 different groups, then performed a Spearman rank correlation test on these values against their growth, biofilm, and biofilm:growth activities. The results showed that the presence of certain moieties was significantly correlated with their activity (Table 2). Specific moieties, such as aromatic groups, fused benzene rings, and primary or secondary amines were significantly correlated (p < 0.05) with either biofilm or growth inhibition. Overall, these results gave support to hypothesis that certain groups of structures were more prevalent among the active compounds in the screen. With this in mind, a more intensive analysis was performed to relate families of structures to their activities.

Table 2.

Spearman's correlation of specific chemical moieties with activity

| Biofilm/Growth |

Growth |

Biofilm |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moiety | Spearman r | p-value | Spearman r | p-value | Spearman r | p-value |

| Aromatic ring | −0.02 | 0.72 | −0.12 | 0.02 | −0.20 | 0.00 |

| Ether | 0.05 | 0.34 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.18 | 0.00 |

| Aromatic bond | −0.02 | 0.71 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.18 | 0.00 |

| COiPr | −0.03 | 0.61 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.18 | 0.00 |

| Macrocycle groups | −0.08 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.37 | −0.18 | 0.00 |

| Etheric oxygen | 0.05 | 0.37 | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.17 | 0.00 |

| Arene | −0.01 | 0.88 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.17 | 0.00 |

| Non-ring bonding | 0.01 | 0.85 | −0.07 | 0.17 | −0.17 | 0.00 |

| Acylic-bonds | 0.01 | 0.85 | −0.07 | 0.17 | −0.17 | 0.00 |

| Non-aliphatic carbon and in a ring | −0.01 | 0.84 | −0.06 | 0.26 | −0.17 | 0.00 |

| H-pyrrole nitrogen | −0.01 | 0.90 | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.17 | 0.00 |

| Cis or trans double bond | −0.03 | 0.56 | −0.05 | 0.32 | −0.16 | 0.00 |

| Alanine side chain | 0.01 | 0.82 | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.15 | 0.00 |

| Non-ring atom | 0.01 | 0.86 | −0.07 | 0.15 | −0.15 | 0.00 |

| i-PrO | 0.07 | 0.17 | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.15 | 0.00 |

| THPO | 0.03 | 0.60 | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.15 | 0.00 |

| Not mono-hydrogenated | 0.04 | 0.43 | −0.05 | 0.29 | −0.15 | 0.00 |

| Me3N+ | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.73 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| MeO | 0.03 | 0.62 | −0.07 | 0.18 | −0.14 | 0.00 |

| COsBu | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.07 | 0.15 | −0.14 | 0.00 |

| CF3 | 0.04 | 0.41 | −0.08 | 0.14 | −0.14 | 0.01 |

| Fused benzene rings | 0.02 | 0.75 | −0.12 | 0.02 | −0.14 | 0.01 |

| Hydrogen Atom | 0.04 | 0.49 | −0.09 | 0.07 | −0.14 | 0.01 |

| F, Cl, Br, or I | 0.05 | 0.37 | −0.16 | 0.00 | −0.14 | 0.01 |

| Primary or secondary amine | −0.02 | 0.71 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.01 |

| tBuO | 0.06 | 0.21 | −0.17 | 0.00 | −0.13 | 0.01 |

| COEt | −0.01 | 0.91 | −0.07 | 0.18 | −0.13 | 0.01 |

| iBuOOC | 0.07 | 0.15 | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.01 |

| Ortho-substituted ring | −0.03 | 0.55 | −0.08 | 0.14 | −0.13 | 0.01 |

| EtO | 0.06 | 0.24 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.01 |

First, to ensure that selection of active compounds was not biased due to overrepresentation by certain clusters, we analyzed the correlation between the number of drugs within each cluster and number of active drugs within that same cluster. Certain structural families are overrepresented in the FDA drug library used in this study. For example the MDS cluster 270 alone contains 29 drugs that are all glucocorticoid and other similar steroids such as progesterone. Out of these 29, 10 either increased or decreased the biofilm:growth ratio by 10%, including drugs that inhibit growth by more than 50%. By comparison, cluster 5 contains 22 nucleoside analogs and only 1 drug in this cluster is active. As another example, 4 drugs out of 9 were found to be active in cluster 11, which contains polycyclic drugs. We found that there was no significant correlation between cluster size and number of active compounds, using Spearman's rank correlations coefficient (p = 0.39) (Figure S1).

Steroid family molecules

Cluster 270 is another interesting collection containing steroid family drugs. With 29 compounds in this structure-based cluster, it is the largest group in this study. Of the active drugs within Cluster 270, progesterone had the largest effect. When incubated with F. novicida, progesterone decreased biofilm formation by fold18- (Table 1) and also inhibited growth by fold13-. Thus, the biofilm:growth ratio was 1.38. Prokaryotes do not make steroid hormones, so the bacterial target of these compounds is of great interest for further study. However, since the effect on bacterial growth is so significant, progesterone would not be considered an antibiofilm compound.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Clusters 50 and 52 from the MDS analysis contained 4 structurally similar drugs, all of which are tyrosine kinase inhibitors used to treat various forms of cancer: apatinib, lapatinib ditosylate, erlotinib HCl, and desmethyl erlotinib (Desmethyl erlotinib is the active metabolite of erlotinib HCl). Both lapatinib and erlotinib HCl selectively interrupt epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathways, while apatinib inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR2). Interestingly, the 2 EGFR inhibitors had significant (and opposite) effects on F. novicida while apatinib did not. Lapatinib was the strongest promoter of biofilm formation found in the study (1.58-fold), and it also had a slight increased growth (1.16-fold) for a biofilm:growth ratio of 1.36 (Table 1). Erlotinib HCl had essentially no effect on growth (1.13-fold increase), but significantly decreased biofilm formation (fold2-), resulting in a biofilm:growth ratio of 0.64. Since this compound had only a small effect on growth, it meets our criteria for a potential antibiofilm compound.

Clinically related but structurally diverse drugs used to treat cancer were also identified to have a significant impact on Francisella growth and biofilm formation. Imatinib mesylate (platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGF-R) inhibitor; cluster 137) slightly increased growth by 1.10-fold. Nilotinib (BCR-ABL inhibitor; cluster 114) significantly decreased biofilm formation (2-fold) without significantly changing growth. Lansoprazole (EGFR autophosphorylation inhibitor; cluster 177) was identified within the top 10 compounds that promoted biofilm formation in F. novicida, with a biofilm:growth ratio of 2.6 (Table 1B). The significance of these effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on Francisella is not known, though a role for bacterial tyrosine kinases has recently been demonstrated in other bacteria, including in biofilm production.32–34

mTOR inhibitors

The MDS cluster 3 contains 2 inhibitors of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), rapamycin, and temsirolimus. mTOR is a serine/threonine protein kinase that modulates eukaryotic cell growth in response to stimuli such as nutrients and growth factors and is commonly dysregulated in various cancers. Rapamycin binding to mTOR specifically blocks substrate recruitment.35 Rapamycin and temsirolimus had similar activities in our screen: growth was slightly increased by 1.13 and 1.26-fold, and biofilm was increased by ∼fold2-, resulting in biofilm:growth ratios of 0.47 and 0.43, respectively (Table 1C). The similar activity was expected due to the very similar chemical structures. Bacterial Ser/Thr kinases have been fairly recently described in bacteria.36 The mechanism by which these Ser/Thr kinase inhibitors promote F. novicida growth and biofilm formation is unknown.

Estrogen-receptor associated compounds

As another example of surprising results found from our screen, we were interested to identify estrogen-receptor associated compounds (cluster 83 in the MDS analysis) as significantly affecting biofilm formation in F. novicida. This was surprising as the pathways of estrogen synthesis appear to be restricted to higher eukaryotes and are not known to be present in bacteria. We identified toremifene citrate, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), as a compound with a very high biofilm:growth ratio. Toremifene has been previously identified in a FDA-approved drug screen to strongly inhibit Ebola virus infection.1 Toremifene significantly inhibited bacterial growth (6.7-fold, Table 1A; Table S1) with a smaller effect on biofilm formation (2-fold inhibition), leading to the high biofilm:growth ratio (3.6). However, due to the significant growth inhibition, we did not consider it a viable antibiofilm drug. Toremifene was able to increase the survival time (measured by mean time to death) of F. novicida infected wax worm larvae (Fig. 5B), and mice (Fig. 5C), likely through this antibacterial activity.

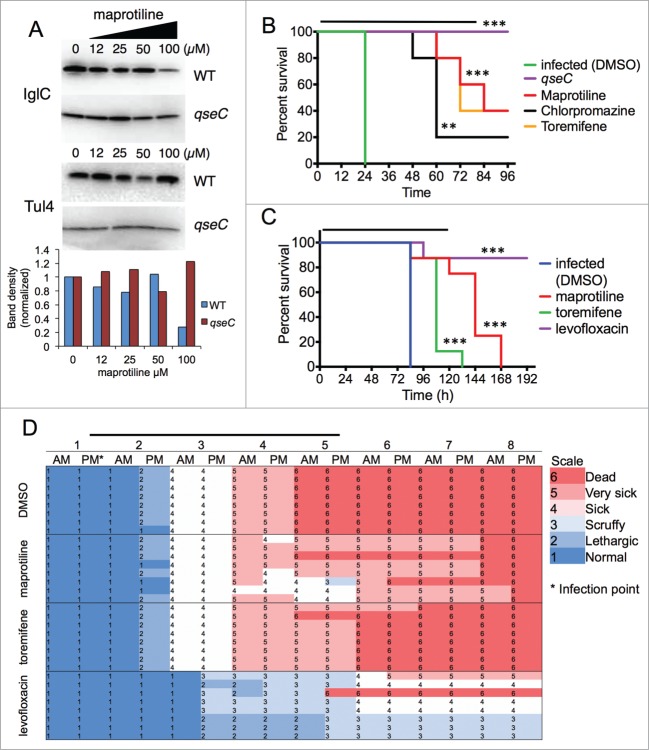

Figure 5.

For figure legend, see page 11. Figure 5 (See previous page). FDA-approved drug maprotiline significantly prolongs survival of F. novicida infected G. mellonella and mice. (A) Treatment of F. novicida bacteria with 100 µM maprotiline led to downregulation of IglC expression in a QseC dependent manner. Tul4 is used as a control for protein expression. Band intensity analysis is shown in the lower panel of A. (B) Galleria mellonella were injected with equal CFUs of F. novicida, and then were subsequently treated (injected with 10 µL) every 24 hours for 4 d Wax moth larvae treated with chlorpromazine, maprotiline, or toremifene showed significantly prolonged survival with F. novicida infection compared to the DMSO-treated control (p < 0.01). Significance was determined by log-rank test. qseC mutant infected G. mellonella had no deaths confirming the role of QseC in virulence. The levofloxacin-treated group also had no deaths (data not shown). (C) Mice were infected (intranasal) with 65 LD50 F. novicida, and then were subsequently treated at t = 1 hour, then every day for 5 d Animals treated with maprotiline and toremifene showed significantly prolonged survival with F. novicida infection compared to the DMSO-treated control (p < 0.01). Survival from DMSO-treatment was significantly different than maprotiline-treatment (p = 0.0006, Median time to death: 84 vs. 144 hours). Toremifene treatment was also significantly different than DMSO-treatment (p = 0.0006, Median time to death: 84 vs. 108 hours). Levofloxacin was used as a control, and rescued all but one of the mice. Significance was determined by log-rank test. (D) As can be seen from the health scores, the maprotiline-treated mice were very sick, but survived much longer than the untreated (DMSO) mice. ***indicates p < 0.001, **indicates p < 0.01, compared to untreated control. The bars over B, C, and D indicate the time of treatment.

Of further interest, the screen identified raloxifene (Evista), another selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) used in the treatment of osteoporosis.37 Evista decreased F. novicida growth by 48%, but increased both F. novicida biofilm formation (1.42-fold increase) as well as the biofilm:growth ratio (2.74-fold increase).

In a structurally distinct cluster (308), we identified another estrogen-receptor associated fulvestrant. As a selective estrogen receptor down-regulator (SERD), fulvestrant is used to down-regulate the estrogen receptor in the treatment of post-menopausal breast cancer.38 We found that fulvestrant also strongly upregulated F. novicida biofilm formation (1.55-fold), the second highest increase in our study (Table 1; Table S1), and the biofilm: growth ratio increased to 1.45. Importantly, fulvestrant did not have a significant effect on growth, thus it might be of interest as a pro-biofilm compound. By bioinformatics analysis there is no Francisella homolog to the estrogen receptor, thus the bacterial target of these compounds is unknown.

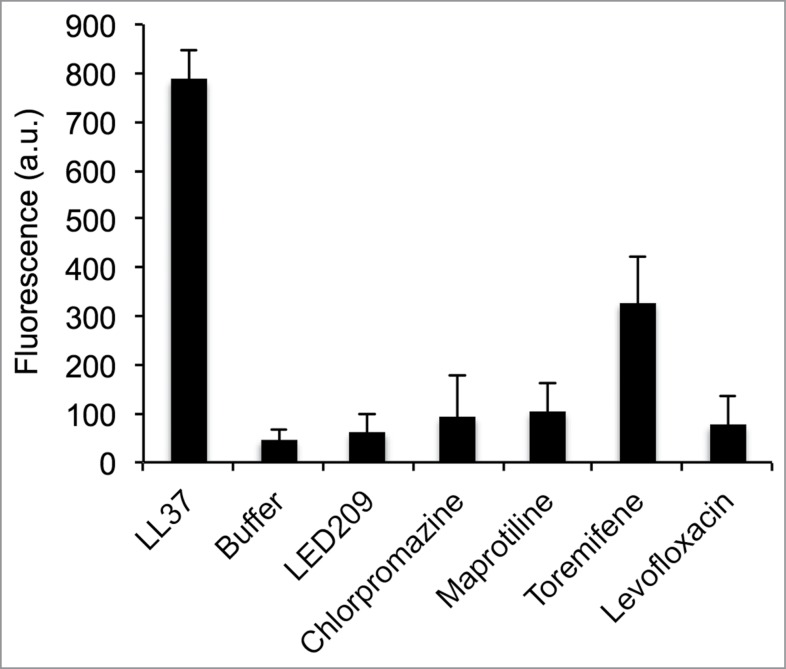

Membrane depolarization of Francisella is caused by the SERM toremifene but not maprotiline

Some antibacterial compounds can act by disrupting or disturbing bacterial membranes as their mechanism of action, without having a specific intracellular target. As SERMs are positively charged at neutral pH and largely hydrophobic, it is possible that they interact with the anionic bacterial membrane. Due to the absence of estrogen receptor homologs in Francisella, we sought to find another explanation for their activity by examining the effect of the SERM compounds on the Francisella membrane. To evaluate the potential effects of the selected drugs on F. novicida cytoplasmic membranes, we used the membrane-potential-sensitive fluorescent dye DiSC3(5).39 DiSC3(5) is taken up by the cells from the media and quenches when concentrated inside the bacterial cells. When membrane is depolarized due to pore formation or other disturbances of the bacterial membrane, the dye is released causing a measurable increase in fluorescence. We used the pore-forming cationic antimicrobial peptide, LL-37, as the positive control for membrane disruption (5 µM).23,40,41 As expected, LL-37 induced significant membrane depolarization (Fig. 4). The PCA compounds maprotiline and chlorpromazine caused a very low level of membrane depolarization at 5 µM. The SERM toremifene (5 µM) caused significant membrane depolarization, ∼30% more than buffer alone. Levofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic capable of inhibiting F. novicida growth by targeting topoisomerase enzymes in the bacteria (Table 1) did not show significant membrane depolarization, nor did LED209, a virulence inhibitor that targets QseC in Francisella.10 These results suggest that the SERM toremifene may be having a direct effect on the bacterial membrane rather than having an estrogen-receptor like target. Through this effect, this compound may then be indirectly affecting bacterial biofilm production via the well-known bacterial stress response pathways through which the bacteria respond to significant alterations to the membrane caused by membrane-active agents.42

Figure 4.

Membrane depolarization assay. The membrane potential sensitive dye DiSC3(5) was incubated with F. novicida. Fluorescence increase upon addition of drug or control was measured at 622 nm excitation/670 nm emission. Toremifene showed a significant increase in fluorescence compared to the buffer control (p < 0.01), but significantly less than LL37 peptide (20 µg/mL) (p < 0.01). This suggests partial membrane depolarization by 5 µM toremifene. The other drugs tested did not cause significant membrane depolarization.

Polycyclic antidepressants (PCA) and antipsychotics cluster by cheminformatics analysis.

To further investigate the structure-activity relationship of the compounds identified in this screen we performed MDS followed by hierarchical clustering on each of the 420 drugs (Fig. 2). In this analysis, when clusters were associated with the biofilm:growth ratio data, certain clusters become identifiable (Fig. 2A). For example, one of the small black spheres in the lower left of Figure 2A is cluster 11, which includes the compounds chlorpromazine (typical antipsychotic), maprotiline, clomipramine and mianserin (norepinephrine reuptake blocking PCAs), chlorprothixene, clozapine, and olanzapine (atypical antipsychotics), and olopatadine (antihistamine). Each of these drugs have tri- or tetracyclic structures. Within the smaller cluster 185 were doxazosin (α-adrenergic blocker, various uses) and iloperidone (atypical antipsychotic), which are monoamine antagonists (including norepinephrine) (Fig. 2B). In cluster 185, iloperidone inhibited growth by 46%, inhibited biofilm by 27%, leading to a biofilm:growth ratio of 1.21. Doxazosin mesylate (cluster 185), (an α-1 adrenergic receptor blocker), inhibited growth 83%, but inhibited biofilm formation only 20%, leading to a biofilm:growth ratio of 4.7, the highest biofilm:growth ratio seen in our screen. However, the toxicity of doxazosin mesylate to F. novicida eliminated it from further study.

Next, to complement the MDS analysis, hierarchical clustering was performed using the structures of the 420 drugs in the screen paired with the biofilm, growth, and biofilm: growth data (Table S1). Graphed in phylogenetic tree format, the hierarchical clustering again demonstrates the structural similarity of the clusters 11 and 185 from the MDS analysis (Fig. 2C and 2D). Also from this graph, it is observable that the majority of the drugs tested do not have a significant impact on either biofilm or growth, as would be expected.

The structurally similar group (Cluster 11) of polycyclic antidepressant drugs chlorpromazine, maprotiline, and others all inhibited biofilm formation. We chose 2 compounds for further analysis in the study: maprotiline and chlorpromazine (cluster 11) since these drugs appeared to have the largest effect on biofilm inhibition (Fig. 2D). Chlorpromazine, a dopamine and potassium channel inhibitor, inhibited biofilm formation 93%, and had a biofilm:growth ratio of 0.33 but inhibited growth by fold5- and thus was excluded from further study. Maprotiline (a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) was the strongest compound to inhibit biofilm with a biofilm:growth ratio of 0.12 and only inhibited growth by 47% (Table 3). Thus, maprotiline was chosen for further study as a potential antibiofilm compound.

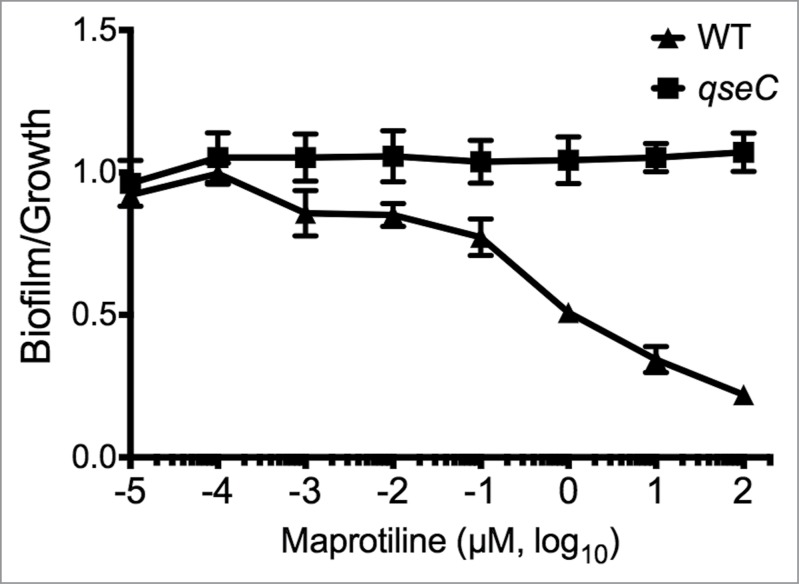

Investigation into the PCA target in F. novicida

Because of its known role in biofilm production in Francisella and its reported potential to be a receptor for norepinephrine,10 we hypothesized that QseC was a possible target of maprotiline activity. In order to investigate potential target maprotiline, we tested its effect on the qseC mutant in F. novicida in comparison with WT. QseC and the response regulator QseB/PmrA are known regulators of biofilm formation and virulence in F. novicida.13 In E. coli, QseC is reported to be a bacterial ligand for norepinephrine and LED209, and Francisella QseC is homologous to E. coli QseC.10 Using antibiofilm assays, we tested to see if the activity of maprotiline and chlorpromazine was QseC-dependent. We used levofloxacin as a control since it decreased biofilm formation and growth proportionally (Table 1), independent of QseC. As expected, levofloxacin significantly decreased both biofilm and growth in a dose-dependent manner resulting in an unchanged biofilm:growth ratio in both WT and the qseC mutant (data not shown). In our study, we found that maprotiline was effective in lowering the biofilm:growth ratio of WT Francisella at concentrations as low as 0.01 µM and the greatest difference being observed at 100 µM, while the qseC mutant was unchanged (Fig. 3). Chlorpromazine also shows QseC dependence (data not shown) but maprotiline was more effective than chlorpromazine in lowering the biofilm:growth ratio. This may be due to the greater degree of growth inhibition by chlorpromazine (80%), which led to it being down-selected out of consideration as an antibiofilm compound. This data correlates well with our data showing that qseC is deficient in biofilm formation (∼60% of WT) and with the activity of a drug known to target QseC (LED209), which also inhibits biofilm formation (Figure S2). Interestingly the structure of maprotiline (Figure S4) is very different than the structure of LED209, suggesting that important differences in mode of action may be involved. Thus, the anti-biofilm activity of maprotiline can be said to be dependent upon QseC in F. novicida.

Figure 3.

QseC dependence of polycyclic antidepressant drug effect on F. novicida biofilm:growth ratio. In wild-type bacteria, the dose-dependence of maprotiline on the biofilm:growth ratio is demonstrated, with significant effects seen as low as 0.01 µM. In the qseC mutant, the dose-dependent effect of maprotiline is abrogated, suggesting that QseC may be the target of this compound.

Maprotiline treatment downregulates the expression of virulence factor, IglC, in F. novicida

We hypothesized that since QseC is the probable target of maprotiline, and if QseC were able to signal to the response regulator PmrA/QseB, then maprotiline would decrease expression of FPI genes by inhibiting signaling through PmrA/QseB, which is known to regulate FPI expression.19 In order to demonstrate that maprotiline is able to inhibit the expression of FPI genes, we incubated F. novicida with a titration of maprotiline and probed for IglC levels by western blotting. Our results show that maprotiline treatment of 100 µM significantly decreased IglC protein expression (Fig. 5A). This effect was shown to be QseC dependent, as the qseC mutant did not show the same decrease in IglC expression. These results indicate that maprotiline inhibits the expression of IglC, a known Francisella virulence factor, in a QseC-dependent manner. In order to determine impact of maprotiline on pathogenicity, we next tested maprotiline treatment of waxworm and murine in vivo infection models.

FDA-approved drug maprotiline prolongs survival of Galleria mellonella

It has previously been shown that waxworm larvae (G. mellonella) is a sensitive model for Francisella infection.24,26,43 To evaluate the ability of selected drugs to prolong survival of infected G. mellonella, larvae were inoculated with 10 µL of PBS containing a lethal dose of F. novicida and treated with selected drugs. We found that the polycyclic compounds maprotiline and chlorpromazine and the SERM, toremifene, all significantly prolonged survival in the waxworm model (Fig. 5B), with maprotiline having the strongest effect. Our in vitro results suggest that toremifene and chlorpromazine are highly antimicrobial (85% and 80% killing, respectively), while maprotiline acts more through the TCS and has an antivirulence activity against F. novicida through downregulation of IglC expression, and is significantly less antimicrobial (47%). Of course, any direct antimicrobial effect of these compounds will promote waxworm survival in this study, but the effect of maprotiline is greater than would be expected based on its antimicrobial activity alone. The larvae infected with the qseC mutant F. novicida had no deaths in the 96-hour study confirming that the qseC mutant is avirulent. The levofloxacin-treated group all survived, showing that they were rescued by treatment with this antibiotic (data not shown).

FDA-approved drug maprotiline prolongs survival of F. novicida infected mice

To confirm the ability of maprotiline to rescue Francisella infected organisms, this compound was tested in a murine Francisella infection model. The intranasal infection of mice with F. novicida at ∼65 LD50 results in death after approximately 5 days, as well as systemic replication of bacteria in the lungs, liver, and spleen. We infected BALB/c mice with 1000 CFU intranasal F. novicida and subsequently treated groups with intraperitoneal injections of maprotiline (60 mg/kg), levofloxacin (6 mg/kg), or 5% DMSO no drug control 1 hr post-infection, and daily thereafter for 5 days, following methods described by Johansen et al.1

Maprotiline-treatment resulted in a significant prolonged survival in vivo (Fig. 5C). Mice treated with maprotiline and toremifene showed significantly prolonged survival with F. novicida infection compared to the DMSO-treated control (p < 0.01). Levofloxacin was used as a control, and rescued all but one of the mice, significantly greater than DMSO and maprotiline groups (p < 0.001), as expected. Maprotiline-treatment resulted in an increase in survival time (p = 0.0006, median time to death: 84 vs. 144 hours), despite their scores of severe illness (Fig. 5D). This result for maprotiline exceeded the survival of toremifene treated mice, despite the significant antimicrobial activity of toremifene against F. novicida, suggesting that the maprotiline effect may be due in part to the repression of IglC expression, thus regulating F. novicida virulence. In support of our hypothesis, the maprotiline treated mice generally survived during the 5 d of treatment, but once the treatment stopped, the mice rapidly succumbed to the infection.

A second study with 100 LD50 showed similar results (Figure S3). In this experiment, the bacterial burden within the lung, liver and spleens was determined. It can be seen that at 48 hours, the number of bacteria in the maprotiline treated organs does not differ from the F. novicida infected lung, liver and spleens (suggesting that the maprotiline is not acting as an antibacterial compound), while the levofloxacin significantly reduces the number of bacteria in the organs. This data suggests that maprotiline-treatment reduces Francisella virulence, which was confirmed by the in vitro experiment showing that maprotiline-treatment reduced the expression of the Francisella virulence factor IglC in a QseC-dependent manner. All the mice died once maprotiline treatment was stopped, suggesting the reversibility of this inhibition.

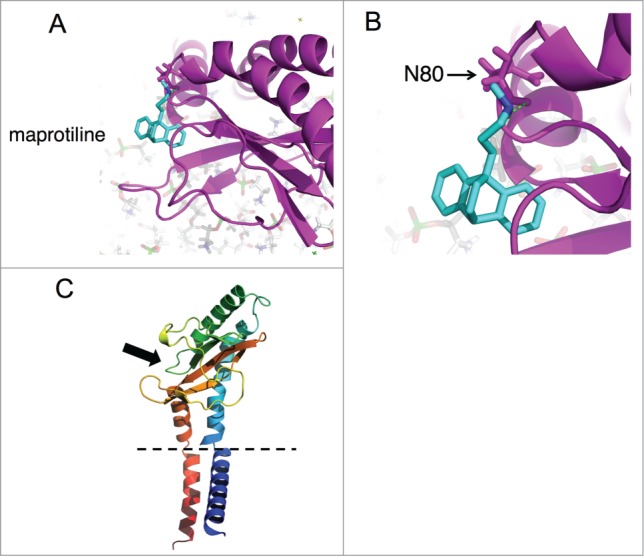

Modeling and prediction of binding site

Based on our modeling of the predicted F. novicida QseC structure and docking studies (Fig. 6), we speculate that the maprotiline binding site will be in the periplasmic sensor domain of QseC very near the predicted norepinephrine (NE) binding site, and may potentially interact with the same residues. Using AutoDock Vina to model the binding of maprotiline and NE to the predicted structure of F. novicida QseC, we found that the lowest energy binding sites of both compounds were reliant on polar contact with asparagine 80 (N80) (Fig. 6B). Based on our preliminary analysis, we believe that the lowest energy binding sites of maprotiline will include Asn80, Lys81, and the side chains of the surrounding aromatic residues. Maprotiline is predicted to make hydrophobic contacts with the aliphatic chain of K81 and the side chains of surrounding aromatic residues. NE also made polar contact with water and the backbone atoms of surrounding aromatic residues. These results could provide the basis for future mutational studies of the residues required for the ligand-protein interaction.

Figure 6.

Computational modeling of maprotiline interaction with F. novicida QseC. (A) The predicted structure of the sensor region QseC is shown as predicted by I-Tasser. The sensor domain is predicted to include amino acid 37–175. The periplasmic region of QseC contains the predicted binding site for maprotiline and also for NE by AutoDock Vina computational modeling. Maprotiline was found to preferentially interact with the sensor domain of periplasmic loop of QseC at the site shown in (A). (B) This site includes a close predicted interaction with amino acid N80 in the QseC periplasmic loop (B). (C) The general location of this loop on QseC is shown in (C). The periplasmic region of QseC contains the predicted binding site for maprotiline and also for norepinephrine by computational modeling (indicated by a black arrow). The histidine kinase domain (not shown) is located in the bacterial cytoplasm, following one of the TM domains. The dashed lines represent the bacterial membrane.

Discussion

It is important to identify new therapeutics against F. tularensis, a Class A Select Agent, in order to increase our preparedness in case of a bioterrorism event with this pathogen, possibly with antibiotic resistant strains. There has been a recent effort to repurpose existing and approved drugs for novel uses. With this in mind, we screened for the antibiofilm activities of 420 drugs in a FDA-approved drug library, seeking this activity for these compounds. Our goal was to identify potent antibiofilm compounds that could potentially be useful as antivirulence compounds for augmenting treatment for Francisella infection by screening F. novicida.

Use of the biofilm screening criteria as a model for a virulence phenotype allowed identification of compounds other than strictly bactericidal or bacteriostatic compounds. A previous study had screened a library of FDA-approved of 1012 compounds and identified multiple known antibiotics that were antimicrobial for Francisella, including clindamycin, erythromycin, lomefloxacin, and tetracycline, but identified no new promising antibiotics.2 We wanted to identify compounds that would affect Francisella virulence rather than be bactericidal, for possible use in antibiotic-resistant cases or as an adjuvant to standard antibiotic treatments.

We employed well-established cheminformatic methods to analyze the relationships of compounds identified in the screen,44,45 comparing structural characteristics with activity. Using this approach, we identified a cluster of polycyclic antidepressant molecules, and in particular maprotiline, for further study.

Toremifene has been previously identified in a FDA-approved drug screen to strongly inhibit Ebola virus infection,1 although the mechanism was not determined in that study. We were very interested to identify toremifene citrate as a compound that led to an increased biofilm:growth ratio in F. novicida but also had high antibacterial activity. Since SERMs are positively charged at neutral pH and are largely hydrophobic, it is possible that they interact with the anionic bacterial membrane, but it is unknown how this may influence biofilm production. Our membrane depolarization experiment supports the hypothesis that SERMs such as toremifene are membrane acting, and may induce a bacterial stress response, which then leads to an alteration in biofilm production as well as growth inhibition. The result is an increased biofilm:growth ratio since the reduction in biofilm formation was of less magnitude than the reduction in growth. Fulvestrant is a SERD that did not inhibit F. novicida growth, but instead promoted F. novicida biofilm formation. This suggests that fulvestrant may be of further interest for the mechanism by which it promotes biofilm formation. Since there is no Francisella homolog to estrogen receptors, the bacterial target of both of these compounds was not clear and was subjected to further study. We found that toremifene citrate treatment strongly caused membrane permeabilization of F. novicida, suggesting that this was a possible mechanism of its antibacterial action. We also tested the ability of the SERM toremifene to prolong survival as a treatment of F. novicida infection. Toremifene prolonged the survival of the infected larvae, suggesting that the effect of this compound in vivo may be to lower bacterial replication through its antibacterial activity.

Steroid family drugs were the largest group of compounds in the study; however, only progesterone was identified to have significant impact on growth and biofilm formation, although it does not meet our criteria of being an antibiofilm drug due to its strong inhibition of growth. While the mechanism of antibacterial activity of progesterone has not been investigated in Francisella, it has been studied in other gram-negative bacteria. It has been shown that progesterone is antimicrobial in Neisseria and that progesterone binds cytoplasmic membrane proteins 3 times more efficiently than the native membranes without proteins. It was suggested that the mechanism could be a hydrophobic interaction of progesterone with membrane proteins and also that it binds to and inhibits respiratory enzymes and inhibits oxygen uptake.46 We also tested estradiol in the screen (in cluster 270 containing progesterone) but it did not inhibit growth or biofilm, matching the published result that estradiol only slightly changes oxygen uptake in Neisseria. Other reports suggest that progesterone, similar to the potential mechanism of SERMs, can interact with and disrupt phospholipids in the membrane potentially leading to bacterial cell lysis.47,48

Our screen also identified tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), most of which are currently FDA-approved to treat various forms of cancer, as strongly increasing F. novicida growth and biofilm formation. Lapatinib was identified as being the strongest promoter of Francisella biofilm formation, and other TKIs were strong promoters of growth. Interestingly, other studies have identified certain TKIs, including lapatinib, as inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis intramacrophage replication.49 The significance of this effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Francisella is not known, although a role for bacterial tyrosine kinases has recently been demonstrated in other bacteria, including in virulence and biofilm production.32,33

Inhibitors of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) were found to promote biofilm formation. mTOR is a serine/threonine protein kinase of eukaryotic cells, and is commonly dysregulated in various cancers.35 Bacterial Ser/Thr kinases have been recently described in other bacteria, though not yet for Francisella.36 The mechanism by which these Ser/Thr kinase inhibitors promote F. novicida biofilm formation is unknown; however, a bacterial Ser/Thr kinase is annotated in F. novicida and F. tularensis (FTN_0459/FTT_1298) in the form of an UbiB domain protein.50

The active compounds identified within the MDS cluster 11 were mainly polycyclic antidepressant drugs that inhibited biofilm formation. Further examination revealed that 2 of these compounds, maprotiline and chlorpromazine, were structurally similar to each other and also had the first and fifth lowest biofilm:growth ratio. In FDA-approved uses, maprotiline and chlorpromazine are both antagonists on postsynaptic receptors, including H1 histamine, D2 dopamine, and 5-HT2 serotonin receptors with differing specificities. Chlorpromazine has broader specificity, and is considered to be low-potency typical antipsychotic. Chlorpromazine has been shown to inhibit biofilm formation in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium,51 and the authors suggested that the mechanism is to inhibit bacterial efflux pumps. When applied at 720 µM, the biofilm inhibition by chlorpromazine against S. typhimurium was to a similar to what we observed in Francisella using 100 µM. However, chlorpromazine is strongly inhibitory to F. novicida growth, so it does not meet the criteria for an antibiofilm compound. Maprotiline, on the other hand, is a second-generation tetracyclic antidepressant, a norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitor with more strong inhibitory activity to the H1 histamine receptor compared to chlorpromazine. The antibiofilm activity of maprotiline has not been previously described in the literature; it is only slightly inhibitory to F. novicida growth (passing our 50% cutoff) and so meets the criteria for being an antibiofilm drug, and so was selected for further study.

The ability of F. novicida to form biofilm has been previously shown by our group to be partly dependent on the 2-component system PmrA/QseB and QseC,15 and we have previously shown the ability of norepinephrine to induce biofilm formation in F. novicida (data not shown). QseC has also been shown to be necessary for virulence factor expression and pathogenicity. The natural ligand of QseC has not been identified in Francisella. However, following the E. coli system, it may be a norepinephrine-like compound produced by Francisella. Maprotiline may be acting as a competitive inhibitor, binding to QseC and preventing the natural ligand from activating the TCS.

In order to investigate potential targets of maprotiline, we tested whether its effect was dependent on QseC, by testing qseC mutant in comparison with WT in an antibiofilm assay. We showed that the antibiofilm activity of maprotiline is dependent on QseC, similar to reports of the anti-virulence drug LED209 being QseC-dependent.10 As expected, the fluoroquinolone antibiotic levofloxacin and the SERM toremifene citrate did not show QseC-dependence.

We demonstrated the ability of maprotiline to inhibit the expression of QseC-dependent FPI encoded virulence factor IglC, and to prolong the survival F. novicida infected animal models. Since maprotiline's activity is QseC-dependent, this could be explained by its ability to antagonize normal QseC-dependent virulence factor expression during infection and to disrupt PmrA/QseB signaling, which controls the expression of Francisella FPI genes, responsible for virulence.14 Our findings suggest that maprotiline is a repressor of F. novicida virulence both in vitro and in vivo by acting as a competitive antagonist of the natural QseC ligand. Because maprotiline is not a potent antibacterial compound, its ultimate inability to prevent mice from succumbing to F. novicida infection was not surprising. However, during the time that the maprotiline was administered, the mice generally survived, suggesting that despite high bacterial numbers in their organs, the bacteria present were perhaps less virulent. Once maprotiline was discontinued (after 5 days), the mice rapidly succumbed to the infection. Therefore, this study suggests an augmentative role for maprotiline, in which it could be used in combination with antibiotics to potentiate current treatments.

Conclusion

In this study, we have identified a FDA-approved polycyclic antidepressant drug maprotiline that has the potential to reduce the severity of Francisella infection by decreasing virulence, rather than by being bactericidal. This drug appears to be a potent antibiofilm compound and this effect on bacteria has not been previously reported. The antibiofilm effect was determined to be via signaling through 2-component systems (QseC-dependent), which also regulate virulence gene expression of the FPI. We report that maprotiline was able to promote survival of F. novicida infected larvae in our insect infection model. In addition, in a mouse model of infection, maprotiline was able to significantly lengthen the time to death against lethal doses of Francisella while the drug was applied. These in vivo results suggest that this compound may not only decrease biofilm formation in vitro by disrupting TCS signaling, but may decrease Francisella virulence in vivo by disrupting TCS-dependent virulence factor expression. Such an antivirulence approach may prove productive for the discovery of new therapeutics effects against antibiotic resistant pathogens or could be used in conjunction with antibiotics to potentiate their activity.

Materials and Methods

Bacteria and growth conditions

Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida, Strain Utah 112, NR-13 (BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH) was grown at 37°C in Tryptic Soy Broth with 0.1% (w/v) cysteine (TSBC). qseC mutant bacteria (FTN1617, T20 (ISFn2/FRT)) (obtained from BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH) were grown in 20 µg/mL kanamycin, TSBC.

Selleck FDA-approved drug library and screen

A collection of 421 FDA approved drugs (Catalog No. L1300, Selleck) was obtained in 96 well plates as pre-dissolved 10 mM solution dissolved in DMSO, 100 μL/well, stored at −80°C.52 This library contains compounds whose bioactivity and safety was confirmed by clinical trials and all compounds are FDA-approved. The compounds are structurally diverse, medicinally active and are all reported to be permeable in eukaryotic cells. There is data for each compound for the IC50 for approved indications, NMR data, and HPLC data to ensure high purity of the compounds. The drug screening was performed using the crystal violet biofilm assay method described below, with a few changes: 1) Overnight cultures were diluted 1 : 50 in TSBC and 200 µL was put into the wells of 96-well plates and 2) drug or controls were added to each well to 100 µM (2 µL of the 10 mM stock solution).

Crystal violet biofilm assays

The crystal violet assay was performed as previously described,23–26 with modifications. First, fold10- dilutions of drug were made in 100 µL of TSBC in a 96-well plate (BD Falcon 353072). Then, overnight cultures of bacteria were diluted 1:25 into 20 mL of TSBC and 100 μL was added to each well. After 12 h at 37°C the optical densities of the wells were taken at 600 nm for growth. First, bacterial culture was gently removed, then biofilm was fixed at 70°C for 1 h, cooled, and stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet for 15 minutes as previously described.53 The stain was removed and biofilms thoroughly washed. Stain was solubilized by adding 200 µL of 30% (v/v) acetic acid and absorbance was read at 590 nm with a microplate reader.

Similarity Measures and Clustering Schemes

Spearman rank correlation of structure and activity was performed by comparing SMILES of every compound with the biofilm and growth data from the screen. The individual SMILES components were counted and categorized. 222 different categories of moiety were used (i.e., “[NH3]” was counted for tertiary amine, “O=C [OH]” was counted for carboxylic acid, etc.). The presence or number of moieties within the compound was then compared to its activity. The test resulted in correlation and significance from the Spearman r and 2-tailed P-values.

ChemMine Tools was used to obtain data for both the multidimensional scaling (MDS) and hierarchical clustering (github.com/TylerBackman/chemminetools).54 Using metric MDS for clustering in a 3 dimensional scatterplot is performed creating a matrix of item-item distances and then assigning coordinates for each item to represent the distances graphically in a scatter plot. The cmdscale function implemented in R is used for this service (http://stat.ethz.ch/R-manual/R-patched/library/stats/html/cmdscale.html). The three largest eigenvalues were graphed with the clustering results and biofilm:growth ratios using scatter3 in MATLAB.

For a secondary clustering, hierarchical clustering was performed using hclust function implemented in R (http://stat.ethz.ch/R-manual/R-patched/library/stats/html/hclust.html). We used a distance matrix of all-all drug distances generated by subtracting the Tanimoto coefficient (Tc) from one (1 - Tc). The distance matrix is passed on to the actual clustering program that hierarchically joins the most to least similar items with an average cluster-joining rule. From this data, EvolView (code.google.com/p/evolgenius) was used to create the phylogenetic tree.55

Membrane depolarization

The membrane potential of F. novicida was measured using the fluorescence probe [3,3′ - Dipropylthiadicarbocyanine iodide] (DiSC3[5]), as previously described,39 and following manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). An overnight culture of Francisella was inoculated 1:50 in TSBC and grown at 37°C for 5 h. The cells were then centrifuged twice at 4000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and washed (5 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose). The cells were then resuspended (in 5 mM glucose, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20 nM DiSC3[5]), and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. 90 µL of the cell suspensions were put into wells of a black 96-well plate and 10 µL of drug (5 µM) or carrier (5% DMSO in PBS) was added. Fluorescence was read at 622 nm excitation/670 nm emission.

Western blot

The expression of IglC with maprotiline treatment was measured by western blot. A titration of maprotiline was added to F. novicida cultures in TSBC, which were then grown for 20 h. The cells were then lysed and the protein concentration normalized. Two-mercaptoethanol reduced samples were run on a Tris-Glycine gel (4–20%), blotted to nitrocellulose, and probed using IglC and Tul4 mouse monoclonal antibodies (BEI Resources, Manassas, VA). These were then probed with anti-mouse HRP, developed with SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and visualized with a Molecular Imager Gel Doc (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Band intensity was determined using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). IglC band intensity was normalized to Tul4 (control protein).

Galleria mellonella infection model

Galleria mellonella larvae were obtained from Vanderhorst Wholesale (Saint Marys, OH, USA). Eight to 12 larvae of equal size/weight were randomly assigned to each group. Prior to injection, overnight bacterial cultures were normalized to an OD600 of 0.1 (∼109 CFU/mL). A 1 mL tuberculin syringe was used to inject 10 µL of bacteria into the hemocoel of each larvae. Ten µL of drug (5 µM) or vehicle was then injected. Drug treatments were then injected every 24 h. Groups of uninfected larvae were injected with drug as a control. The 5% DMSO in PBS was used as the vehicle for the treatments and as the no drug control. The insects were then observed twice daily for their survival status.

Mouse infection model

The murine infection model was performed as previously described.56 BALB/c mice (9-week-old, female) were obtained from Harlan (Frederick, MD). The animals were then infected intranasally with 650 CFU F. novicida in 30 µL. One hour after challenge, the mice were treated with maprotiline, toremifene, levofloxacin, or a solution of 5% DMSO/PBS with no drug. The compounds were dissolved in DMSO and diluted in PBS to a final formulation of 5% DMSO/PBS. The compounds were administered by intraperitoneal injection (200 μL). The animals were then treated once every day to Day 5 (t = ∼120 h). Mice were monitored for survival status for a total of 12 d after infection. On day 6 after infection, one mouse from each group was either sacrificed (or taken from storage if previously found dead) and the lung, liver, and spleen collected. The organs were homogenized and plated for CFU counting.

The health status of the mice was monitored using a rating system: 1–6. (1 = healthy, 2 = lethargic, 3 = scruffy, 4 = sick, 5 = very sick, 6 = euthanized or found dead). The dosages given to the mice were 60 mg/kg for toremifene and maprotiline, and 6 mg/kg for levofloxacin (average mouse weight = 20 g). This dosage is 1.2 mg per injection for toremifene and maprotiline, 0.12 mg for levofloxacin.

Ethics statement

All animal experiments included in this manuscript were approved by and conducted in compliance with regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval #236) of George Mason University. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2011) and the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2002).

Modeling of maprotiline interaction with QseC

The predicted structure of the sensor region QseC is predicted by I-TASSER.57 The sensor domain is predicted using PFAM analysis of the sequence. Using VMD and NAMD, the model QseC was placed in a model membrane; energy minimization was performed to relieve steric clashes, and the system was then equilibrated for ∼10 ns. AutoDock Vina was used for computational determination of low energy docking poses between maprotiline (and for norepinephrine) with model QseC.58 AutoDockTools was used to generate Protein Data Bank, Partial Charge and Atom Type (pdbqt) files to be used in the docking simulation. The docking was performed using default settings with the following exceptions: system (excluding membrane) was entirely submerged in the box which was set to xyz = 130,130, 130 Å with a grid spacing of 0.2 Å.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests, other calculations, and graphing were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), MATLAB R2014a (The MathWorks, Inc.., Natick, MA), Microsoft Excel 2011 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), and ImageJ (Rasband, W.S., NIH, Bethesda, MD, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. To plot the probability distribution of biofilm:growth ratio with drugs and control in the screen, ratios were binned and the histogram was created using the histogram function in MATLAB.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge technical support from Albert Nwabueze and Collette Marchesseault.

Supplemental Materia

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

Reference

- 1.Johansen LM, Brannan JM, Delos SE, Sho`emaker CJ, Stossel A, Lear C, Hoffstrom BG, Dewald LE, Schornberg KL, Scully C, et al.. FDA-approved selective estrogen receptor modulators inhibit Ebola virus infection. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5:190ra79; PMID:23785035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madrid PB, Chopra S, Manger ID, Gilfillan L, Keepers TR, Shurtleff AC, Green CE, Iyer LV, Dilks HH, Davey RA, et al.. A systematic screen of FDA-approved drugs for inhibitors of biological threat agents. PLoS One 2013; 8:e60579; PMID:23577127; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0060579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birdsell DN, Stewart T, Vogler AJ, Lawaczeck E, Diggs A, Sylvester TL, Buchhagen JL, Auerbach RK, Keim P, Wagner DM. Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida isolated from a human in Arizona. BMC Res Notes 2009; 2:223; PMID:19895698; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1756-0500-2-223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hancock RE. Collateral damage. Nat Biotechnol 2014; 32:66-8; PMID:24406933; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt.2779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackie RS, McKenney ES, van Hoek ML. Resistance of Francisella novicida to fosmidomycin associated with mutations in the glycerol-3-phosphate transporter. Front Microbiol 2012; 3:226; PMID:22905031; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutera V, Levert M, Burmeister WP, Schneider D, Maurin M. Evolution toward high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Francisella species. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69:101-10; PMID:23963236; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jac/dkt321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.La Scola B, Elkarkouri K, Li W, Wahab T, Fournous G, Rolain JM, Biswas S, Drancourt M, Robert C, Audic S, et al.. Rapid comparative genomic analysis for clinical microbiology: the Francisella tularensis paradigm. Genome Res 2008; 18:742-50; PMID:18407970; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.071266.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gestin B, Valade E, Thibault F, Schneider D, Maurin M. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of macrolide resistance in Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica biovar I. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65:2359-67; PMID:20837574; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jac/dkq315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maurin M. New anti-infective strategies for treatment of tularemia. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2014; 4:115; PMID:25191647; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasko DA, Moreira CG, Li de R, Reading NC, Ritchie JM, Waldor MK, Williams N, Taussig R, Wei S, Roth M, et al.. Targeting QseC signaling and virulence for antibiotic development. Science 2008; 321:1078-80; PMID:18719281; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1160354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis MM, Russell R, Moreira CG, Adebesin AM, Wang C, Williams NS, Taussig R, Stewart D, Zimmern P, Lu B, et al.. QseC Inhibitors as an Antivirulence Approach for Gram-Negative Pathogens. mBio 2014; 5; PMID:25389178; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/mBio.02165-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasko DA, Sperandio V. Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010; 9:117-28; PMID:20081869; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrd3013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verhoeven AB, Durham-Colleran MW, Pierson T, Boswell WT, Van Hoek ML. Francisella philomiragia biofilm formation and interaction with the aquatic protist Acanthamoeba castellanii. Biol Bull 2010; 219:178-88; PMID:20972262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell BL, Mohapatra NP, Gunn JS. Regulation of virulence gene transcripts by the Francisella novicida orphan response regulator PmrA: role of phosphorylation and evidence of MglA/SspA interaction. Infect Immun 2010; 78:2189-98; PMID:20231408; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/IAI.00021-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durham-Colleran MW, Verhoeven AB, van Hoek ML. Francisella novicida forms in vitro biofilms mediated by an orphan response regulator. Microbial ecology 2010; 59:457-65; PMID:19763680; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00248-009-9586-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sammons-Jackson WL, McClelland K, Manch-Citron JN, Metzger DW, Bakshi CS, Garcia E, Rasley A, Anderson BE. Generation and characterization of an attenuated mutant in a response regulator gene of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS). DNA Cell Biol 2008; 27:387-403; PMID:18613792; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/dna.2007.0687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santic M, Molmeret M, Klose KE, Jones S, Kwaik YA. The Francisella tularensis pathogenicity island protein IglC and its regulator MglA are essential for modulating phagosome biogenesis and subsequent bacterial escape into the cytoplasm. Cellular microbiology 2005; 7:969-79; PMID:15953029; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00526.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai S, Mohapatra NP, Schlesinger LS, Gunn JS. Regulation of francisella tularensis virulence. Frontiers in microbiology 2010; 1:144; PMID:21687801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohapatra NP, Soni S, Bell BL, Warren R, Ernst RK, Muszynski A, Carlson RW, Gunn JS. Identification of an orphan response regulator required for the virulence of Francisella spp. and transcription of pathogenicity island genes. Infect Immun 2007; 75:3305-14; PMID:17452468; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/IAI.00351-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boguski MS, Mandl KD, Sukhatme VP. Drug discovery. Repurposing with a difference. Science 2009; 324:1394-5; PMID:19520944; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1169920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun R, Wang L. Inhibition of Mycoplasma pneumoniae growth by FDA-approved anticancer and antiviral nucleoside and nucleobase analogs. BMC Microbiol 2013; 13:184; PMID:23919755; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2180-13-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bessoff K, Sateriale A, Lee KK, Huston CD. Drug repurposing screen reveals FDA-approved inhibitors of human HMG-CoA reductase and isoprenoid synthesis that block Cryptosporidium parvum growth. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57:1804-14; PMID:23380723; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AAC.02460-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]