Abstract

Prions are the etiological agent of fatal neurodegenerative diseases called prion diseases or transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. These maladies can be sporadic, genetic or infectious disorders. Prions are due to post-translational modifications of the cellular prion protein leading to the formation of a β-sheet enriched conformer with altered biochemical properties. The molecular events causing prion formation in sporadic prion diseases are still elusive. Recently, we published a research elucidating the contribution of major structural determinants and environmental factors in prion protein folding and stability. Our study highlighted the crucial role of octarepeats in stabilizing prion protein; the presence of a highly enthalpically stable intermediate state in prion-susceptible species; and the role of disulfide bridge in preserving native fold thus avoiding the misfolding to a β-sheet enriched isoform. Taking advantage from these findings, in this work we present new insights into structural determinants of prion protein folding and stability.

Keywords: prion protein, folding, stability, N-terminal domain, octarepeat, globular domain, intermediate state, disulfide bridge

Abbreviations

- TSE

transmissible spongiform encephalopathies

- CJD

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- GSS

Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome

- FFI

fatal familial insomnia

- PrPC

cellular prion protein

- PrPSc

prion

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- OR

octarepeats

- NMDA receptor

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- ADAM family

A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase family

Introduction

Prion diseases or transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE) are a group of fatal neurodegenerative diseases such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker (GSS) syndrome, fatal familial insomnia (FFI), and kuru in humans, bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle, scrapie in sheep and goats, and chronic wasting disease in elk, deer, and moose.1 These maladies can be sporadic, genetic or infectious disorders.2 Prions, the etiological agents of these disorders, are composed of a conformational isoform of cellular prion protein (PrPC) known as PrPSc.3 Compared to PrPC, prions present altered biochemical properties, such as resistance to limited proteolysis and insolubility in non-denaturant detergents, and secondary and tertiary structures. While PrPC contains 40% α-helix and 3% β-sheet, PrPSc is highly enriched in β-sheets. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy analysis showed higher β-sheet (43%) and lower α-helix (30%) content in PrPSc than PrPC.4 The reduction of α-helical content in PrPSc has been also confirmed by hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiments showing no native α-helices in prions.5 Although the insoluble nature of prions hampers the use of high-resolution analytical techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance or X-ray crystallography, a number of studies using low resolution approaches such as limited proteolysis, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, antibody-labeling, electron microscopy, fiber X-ray diffraction and small angle X-ray scattering provided important information on both secondary and tertiary PrPSc structure.6,7

According to the ‘protein-only hypothesis’, the transmission of the disease is due to the ability of a prion to convert PrPC into the pathological form, acting as a template.8 During the course of prion diseases, PrPC is converted into the abnormal form by a conversion process whereby most α-helix motives are replaced by β-sheet secondary structures.7 Point mutations and seeds trigger PrPC to overcome the energy barriers, causing genetic and infectious TSE.9 Information on molecular events leading to sporadic CJD is still lacking, though epidemiological studies indicate being a majority of all prion diseases.10 Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which PrPC is converted into PrPSc is a major challenge in prion research.

Prion Protein Structure and Function

The PrPC is a sialoglycoprotein tethered to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane via a C-terminal glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. Following the cleavage of N-terminal signal peptide, PrPC is exported to the cell surface as a N-glycosylated protein. Its tridimensional structure is highly conserved among mammals,11,12 and it is composed of a flexible unfolded N-terminal domain and an α-helical enriched globular domain (Fig. 1).13 The unfolded N-terminal domain consists of unusual glycine-rich repeats. Residues 59−90 (mouse numbering) form 4 octarepeats (OR), PHGG[GS]WGQ, while residues 51−58 form an octapeptide lacking of the histidine residue (PQGGTWGQ). The OR segment binds copper and other divalent cations such as zinc, nickel, iron and manganese.14–18 Although PrPC and metals share many common physiological functions, such as neuroprotection against apoptosis and oxidative stress, neurite outgrowth, maintenance of myelinated axons, copper homeostasis and synapse formation and functioning, the role of PrPC−metal complexes is still elusive.19 Recently, the role of PrPC-copper complex in protecting neurons by modulating NMDA receptor through S-nitrosylation has been shown.20

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of PrPC structural determinants. Highlighted: N-terminal domain (red line), globular domain (blue line), octarepeat region (OR) with octapeptide sequences (see main text), α-helices (H1, H2 and H3), β-strands (S1, S2), N-linked glycosylation sites (CHO), disulfide bridges (S-S) and glycosylphosphatidylinisotol (GPI) anchor.

The C-terminal domain presents 3 α-helices (spanning residues 143−152, 171−192 and 199−222), a short 2-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, and a short C-terminal tail.13,21 The V-shaped arrangement of the 2 longest helices, the second and the third, forms the scaffold onto which the β-sheet and the first α-helix are anchored. This domain also contains a disulfide bridge linking α2-α3 helices, and the 2 N-linked carbohydrates.

Like many other cell surface proteins, PrPC is exposed to low dielectric constant and different pH values because of its proximity to membranes and the constitutive cycling between plasma membrane and endocytic compartments. As a general mechanism for modulating its activity,22 PrPC can be differentially cleaved in vivo in the central region generating a soluble N-terminal domain and an anchored C-terminal globular domain (truncated form).22–24

Prion Protein Folding and Stability

PrPC is formed by several structural determinants such as unfolded N-terminal domain, octapeptide region, globular domain, and disulfide bridge. In physiological conditions PrPC mostly folds in α-helical conformation, whereas in prion pathogenesis it is converted into the β-sheet enriched isoform PrPSc. To disclose molecular mechanisms inducing the pathological conversion in sporadic forms of prion diseases, a detailed study on the major structural determinants and environmental key factors affecting prion protein folding and stability is required. Recently, we published a study elucidating the contribution of major structural determinants and environmental factors in prion protein folding and stability.25

Comparing folding of full-length and truncated forms, we observed an α-helical conformation for both proteins at neutral and acidic pH, with the full-length more stable than the truncated form. Calorimetric measurements on full-length protein showed ΔG25°C values 4–5 Kcal/mol higher than those obtained with spectroscopic analysis. Since calorimetry measures the amount of released or absorbed heat during chemical reactions and physical changes, taking into account all interactions occurring in protein folding and unfolding, the higher ΔG25°C values obtained by differential scanning calorimetry are due to the interaction of N-terminal tail with C-terminal domain thus suggesting a role for the unfolded N-terminal domain in stabilizing the folded globular part. The flexible N-terminal domain interacts with the folded C-terminal part stabilizing it and favoring its folding, as confirmed by the reversible folding/unfolding process of full-length and the fully irreversible thermal unfolding transition of the truncated form. Therefore the flexible tail of the protein affects folding and stability of globular domain. The contribution of N-terminal domain in stabilizing the protein is pH-dependent because of histidine residues in the OR part acting as pH sensor. At acidic conditions similar to those present in endocytic compartments, histidine residues are mostly positively charged and stability of full-length is reduced. Also in these conditions, full-length is more stable than the truncated form, as indicated by [Urea]1/2 value of 5.7 M and 5.2 M respectively.

As describe above, OR segment represents the major structural determinant in N-terminal domain. In addition to metal binding, OR region is involved in stabilizing full-length protein, preserving its native folding. The lack of only one octarepeat causes the decrease of α-helical content and determines the loss of reversibility, similarly to the truncated form. To conclude, the N-terminal domain modulates the stability of C-terminal domain through the OR segment. Aberrant interactions of N-terminal domain with surrounding proteins or molecules, such as divalent cations, may alter the stabilizing effect on the globular domain permitting its misfolding. Metal dys-homeostasis may therefore induce the formation of non-physiological PrPC-metal complexes, aberrant N-terminal/C-terminal interactions and then globular domain destabilization.

The cleavage of PrPC by zinc metalloprotease ADAM family induces the release of N-terminal domain and the formation of the truncated form. This globular domain is still tethered to membrane and undergoes to the constitutive cycling between plasma membrane and endosomes, with subsequent exposure to different environmental pH values. In the presence of acidic conditions, globular domain unfolds with a 3-state transition mechanism. The transition state is favored at low temperatures, as confirmed by free-energy and [Urea]1/2 values, and it is enthalpically stabilized with respect to the native state by approximately 20 kcal/mol. Interestingly, the highly enthalpically stable intermediate state corresponds to a peculiar metastable folding of PrP only in species susceptible to scrapie such as human, mouse, cattle, and some sheep variants. Scrapie-resistant species, as the sheep variant ARR, do not show the highly enthalpically stable intermediate state. Therefore, this metastable state may represent a common path in the pathological conversion of PrPC to PrPSc. This finding is in agreement with previous observations showing the endosomal recycling compartment as the intracellular site of the conversion.26 The highly enthalpically stable intermediate state is characterized by a repositioning of α1-helix, a new β-sheet between residues 124–128 and residues 151–155, and a larger number of intramolecular salt-bridges and intermolecular hydrogen bonds with water not accessible from the native conformation. The structural rearrangements leading to the formation of the metastable state are compatible with results obtained with low resolution techniques on N-terminally truncated PrP27–30,6,7 and the left-handed β-helix model proposed by Govaerts et al.27 In this model, PrP residues from 90 to 170 are converted into β-strands and subsequently in β-helices, while the globular domain retains its α-helical structure with the disulfide bridge and the glycan moieties located outside the oligomeric core.

TSE, as other neurodegenerative diseases, are characterized by oxidative damage.28–30 The impact of oxidative stress on PrPC disulfide bridge and then on prion conversion is unsolved. For this reason, we investigated the role of disulfide bridge in preserving native folding and protein stability. Previously published in vitro studies have shown that disulfide bridge reduction under denaturing conditions causes the disruption of native tertiary interactions and protein unfolding. In our study, we reduced disulfide bridge in quasi-native conditions, preserving protein folding. While the reduced form of full-length shows a decrease in α-helical content, the reduced globular domain is characterized by larger β-sheet content and hydrophobic surface exposed to the solvent. The increased hydrophobicity on protein surface leads to misfolding and aggregation.

Conclusions

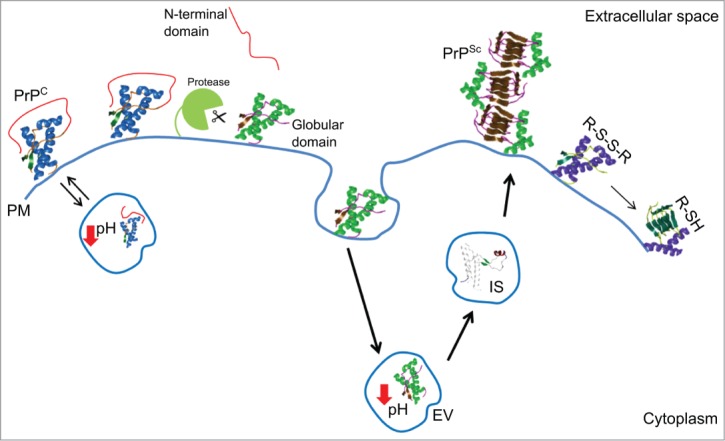

During prion pathogenesis, PrPC undergoes to structural rearrangements leading to the formation of prions. Prions propagate acting as a template, and thus converting new PrPC molecules into PrPSc. In sporadic forms of prion diseases, the early events causing PrPC misfolding and conversion are still unclear. Understanding the major structural determinants in PrPC folding and stability is crucial to disclose the early events leading to prion conversion in sporadic TSE. In our study, we identified the structural elements and environmental key factors in prion protein folding and stability (Fig. 2). These findings allow us to conclude that aberrant N-terminal domain/C-terminal domain interactions or PrPC cleavage may cause protein misfolding in endosomial vesicles, therefore favoring prion conversion.

Figure 2.

Cartoon of the major structural determinants and environmental key factors in prion protein folding and stability. Abbreviations correspond to: cellular prion protein (PrPC); prion (PrPSc); highly enthalpically stable intermediate state (IS); plasma membrane (PM); endosomial vesicles (EV); disulfide bridge (R-S-S-R); free thiol (R-SH).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 1982; 216:136–44; PMID:6801762; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.6801762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benetti F, Geschwind MD, Legname G. De novo prions. F1000 Biol Rep 2010; 2; PMID:20948787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95:13363–83; PMID:9811807; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan KM, Baldwin M, Nguyen J, Gasset M, Serban A, Groth D, Mehlhorn I, Huang Z, Fletterick RJ, Cohen FE, et al.. Conversion of alpha-helices into beta-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90:10962–6; PMID:7902575; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smirnovas V, Baron GS, Offerdahl DK, Raymond GJ, Caughey B, Surewicz WK. Structural organization of brain-derived mammalian prions examined by hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011; 18:504–6; PMID:21441913; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amenitsch H, Benetti F, Ramos A, Legname G, Requena JR. SAXS structural study of PrP(Sc) reveals ˜11 nm diameter of basic double intertwined fibers. Prion 2013; 7:496–500; PMID:24247356; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.27190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legname G, Giachin G, Benetti F. Structural studies of prion proteins and prions. In: Rahimi F, Bitan G, eds., Non-Fibrillar Amyloidogenic Protein Assemblies-Common Cytotoxins Underlying Degenerative Diseases. Taylor & Francis; 2012; 289–317 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Supattapone S. Prion protein conversion in vitro. J Mol Med (Berl) 2004; 82:348–56; PMID:15014886; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00109-004-0534-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benetti F, Legname G. De novo mammalian prion synthesis. Prion 2009; 3:213–9; PMID:19887900; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.3.4.10181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown K, Mastrianni JA. The prion diseases. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2010; 23:277–98; PMID:20938044; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/0891988-710383576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Premzl M, Delbridge M, Gready JE, Wilson P, Johnson M, Davis J, Kuczek E, Marshall Graves JA. The prion protein gene: identifying regulatory signals using marsupial sequence. Gene 2005; 349:121–34; PMID:15777726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wopfner F, Weidenhofer G, Schneider R, von Brunn A, Gilch S, Schwarz TF, Werner T, Schatzl HM. Analysis of 27 mammalian and 9 avian PrPs reveals high conservation of flexible regions of the prion protein. J Mol Biol 1999; 289:1163–78; PMID:10373359; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damberger FF, Christen B, Perez DR, Hornemann S, Wuthrich K. Cellular prion protein conformation and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:17308–13; PMID:21987789; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1106325108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hornshaw MP, McDermott JR, Candy JM. Copper binding to the N-terminal tandem repeat regions of mammalian and avian prion protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995; 207:621–9; PMID:7864852; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown DR, Hafiz F, Glasssmith LL, Wong BS, Jones IM, Clive C, Haswell SJ. Consequences of manganese replacement of copper for prion protein function and proteinase resistance. EMBO J 2000; 19:1180–6; PMID:10716918; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson GS, Murray I, Hosszu LL, Gibbs N, Waltho JP, Clarke AR, Collinge J. Location and properties of metal-binding sites on the human prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98:8531–5; PMID:11438695; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.151038498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones CE, Klewpatinond M, Abdelraheim SR, Brown DR, Viles JH. Probing copper2+ binding to the prion protein using diamagnetic nickel2+ and 1H NMR: the unstructured N terminus facilitates the coordination of six copper2+ ions at physiological concentrations. J Mol Biol 2005; 346:1393–407; PMID:15713489; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh N, Das D, Singh A, Mohan ML. Prion protein and metal interaction: physiological and pathological implications. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2010; 12:99–107; PMID:19767653 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Angelo P, Della Longa S, Arcovito A, Mancini G, Zitolo A, Chillemi G, Giachin G, Legname G, Benetti F. Effects of the pathological Q212P mutation on human prion protein non-octarepeat copper-binding site. Biochemistry 2012; 51:6068–79; PMID:22788868; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi300233n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasperini L, Meneghetti E, Pastore B, Benetti F, Legname G. Prion protein and copper cooperatively protect neurons by modulating NMDA receptor through S-nitrosylation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014; [Epub ahead of print]; PMID:25490055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riek R, Hornemann S, Wider G, Billeter M, Glockshuber R, Wuthrich K. NMR structure of the mouse prion protein domain PrP(121-231). Nature 1996; 382:180–2; PMID:8700211; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/382180a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonald AJ, Millhauser GL. PrP overdrive: Does inhibition of alpha-cleavage contribute to PrP toxicity and prion disease? Prion 2014; 8(2);183–191 PMID:24721836; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.28796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang J, Kong Q. alpha-Cleavage of cellular prion protein. Prion 2012; 6:453–60; PMID:23052041; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.22511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald AJ, Dibble JP, Evans EG, Millhauser GL. A new paradigm for enzymatic control of alpha-cleavage and beta-cleavage of the prion protein. J Biol Chem 2014; 289:803–13; PMID:24247244; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M113.502351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benetti F, Biarnes X, Attanasio F, Giachin G, Rizzarelli E, Legname G. Structural determinants in prion protein folding and stability. J Mol Biol 2014; 426:3796–810; PMID:25280897; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marijanovic Z, Caputo A, Campana V, Zurzolo C. Identification of an intracellular site of prion conversion. PLoS Pathog 2009; 5:e1000426; PMID:19424437; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Govaerts C, Wille H, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE. Evidence for assembly of prions with left-handed beta-helices into trimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101:8342–7; PMID:15155909; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0402254101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brazier MW, Lewis V, Ciccotosto GD, Klug GM, Lawson VA, Cappai R, Ironside JW, Masters CL, Hill AF, White AR, et al.. Correlative studies support lipid peroxidation is linked to PrP(res) propagation as an early primary pathogenic event in prion disease. Brain Res Bull 2006; 68:346–54; PMID:16377442; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guentchev M, Siedlak SL, Jarius C, Tagliavini F, Castellani RJ, Perry G, Smith MA, Budka H. Oxidative damage to nucleic acids in human prion disease. Neurobiol Dis 2002; 9:275–81; PMID:11950273; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yun SW, Gerlach M, Riederer P, Klein MA. Oxidative stress in the brain at early preclinical stages of mouse scrapie. Exp Neurol 2006; 201:90–8; PMID:16806186; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]