Abstract

Objectives: Sexual health discussions between parents and their preadolescent youth can delay sexual debut and increase condom and contraceptive use. However, parents frequently report being uncomfortable talking with their youth about sex, often reporting a lack of self-efficacy and skills to inform and motivate responsible decision making by youth. Intergenerational games may support parent–youth sexual health communication. The purpose of this study was to explore parent and youth perspectives on a proposed intergenerational game designed to increase effective parent–youth sexual health communication and skills training.

Materials and Methods: Eight focus groups were conducted: four with parents (n=20) and four with their 11–14-year-old youth (n=19), to identify similarities and differences in perspectives on gaming context, delivery channel, content, and design (components, features, and function) that might facilitate dyadic sexual health communication.

Results: Participants concurred that a sex education game could improve communication while being responsive to family time constraints. They affirmed the demand for an immersive story-based educational adventure game using mobile platforms and flexible communication modalities. Emergent themes informed the development of a features inventory (including educational and gaming strategies, communication components, channel, and setting) and upper-level program flow to guide future game development.

Conclusions: This study supports the potential of a game to be a viable medium to bring a shared dyadic sexual health educational experience to parents and youth that could engage them in a motivationally appealing way to meaningfully impact their sexual health communication and youth sexual risk behaviors.

Introduction

Adolescents continue to shoulder the burden of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus infection, and teen pregnancy. In the United States, adolescents account for nearly half of all new STI diagnoses, 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus diagnoses, and approximately 7 percent of pregnancies (to teenage girls under 20 years of age).1,2 Additionally, 22 percent of ninth graders used drugs or alcohol before having sex.2 Although school-based sexual health education can reduce these sexual risk behaviors, they may not occur at critical precoital timing or may lack sufficient dose to be effective.3–5

Providing sexual health education in home settings and increasing parental involvement in adolescent sexual health interventions may increase reach, provide more timely sexual health education and skills-based learning, and improve parent and youth communication around sexual health.6 Involving parents has had a demonstrated effect on improved communication as well as on adolescent sexual health outcomes, including increased age of sexual debut and condom and contraceptive use.6–11 However, parents often fail to initiate timely communication regarding risk reduction (delayed sexual debut, as well as condom and contraceptive use), with over 40 percent of youth engaging in sexual activity prior to parental communication on the topic.12 Determinants of successful communication include parents' intentions to communicate and the beliefs that they have the skills to communicate, that they will positively impact their youth's behavior, and that important others would approve.13 Interventions that target communication skills training and involve parents are associated with increased sexual risk communication and youth knowledge, confidence, and comfort regarding communication,14–17 and parental mediation of media use can positively affect youth attitudes and behaviors.18–21 However, delivery through face-to-face and multisession group-based channels limits program reach and fidelity22–25 and ignores parents' and adolescents' motivation to use technology to obtain sexual health information.26

Videogames can facilitate parent–child interaction and promote positive communication.16,27 Computer game–based sexual health interventions have demonstrated impact on delayed initiation of sex, risk reduction behaviors in sexually active youth, and/or improved knowledge, attitudes, and intentions regarding these behaviors.28–34 However, they have primarily targeted youth. An intergenerational game (IGG) is a game that provides an inclusive and shared entertainment experience that is appealing across developmental ages from children to adults, representing a common “meeting ground” for families.35–38 In an IGG both parents and youth can play an active role in winning the game, in contrast to parental monitoring of child-led gaming activities. Health-related IGGs, therefore, could bridge the “communication gap” to induce interaction between parents and their youth as a mediator to positively impact health behaviors. In the health field, and particularly in the realm of sexual health education, IGG-based interventions are rare. Examination of the IGG practices has demonstrated intergenerational interaction,39,40 greater flexibility of player roles where youth adopt leadership roles mentored by older players,35,40 and collaborative engagement where intergenerational player dyads act more cooperatively than same-aged dyads.41

The purpose of this study was to explore parent and youth perspectives to inform the development of an IGG for youth (11–14 years old) and their parents to increase effective parent–child sexual health communication and to delay sexual debut in youth who are not sexually active or to increase condom and contraceptive use in sexually active youth. Specifications on game context, channel, content, design, components, features, and function may inform the design and development of a sexual health educational experience that can reach parents and youth, engage them in a motivationally appealing way, and meaningfully impact their sexual health communication and youth sexual risk behaviors.

Materials and Methods

Eight focus groups were conducted: four with parents (n=20) and four with their 11–14-year-old youth (n=19). Parent and youth groups were conducted separately, averaged five participants per session (range, 2–13), were 2 hours in duration (range, 1.5–2.5 hours), and were conducted in conference rooms at the University of Texas Health Science Center (the most convenient central location for participants). Parents and youth dyads were recruited through flyers and targeted Facebook advertisements. Eligibility criteria included age (youth 11–14 years old), home Internet access, and English proficiency. Written parental consent and youth assent were obtained prior to the study, which was approved by The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston's Center for the Protection of Human Subjects, and gift cards were provided subsequent to the sessions. Doctoral and Master's level researchers, trained in qualitative methods, facilitated the sessions using group moderating techniques to encourage all participants to provide input.42,43 Sessions were audio-recorded.

An adaptive structured interview guide was used to focus on how parents and youth engage in gaming and sexual health communication and to gain their perspectives on desired components and functions of an IGG for sexual health (Table 1). Mock-ups of game graphics, storylines, and illustrated storyboards were developed as exemplars to evoke reactions to treatment elements through iterative group discussion. Participants were shown several storyboards and provided reactions to them. Audio files were transcribed by a transcription company specializing in medical research.

Table 1.

Focus Group Guide Questions (Selection)

| Computer games |

| • What types of computer games/learning activities do you play/engage in? |

| • Where do you play them? On what devices? |

| • What types of games do you play with your parents/child? What makes them fun? |

| Games and parent–child sexual health communication |

| • How comfortable would you feel playing a computer game about dating and sex? |

| • What would make it easier to talk with your parent/child about these topics? |

| • What materials or resources have your parents/you used to talk about dating and sex? |

| • What was your experience using these materials/resources? |

| Design for an intergenerational sexual health game |

| • How comfortable would you feel playing a computer game with your parents/child that talks about sexual health topics? Why or why not? |

| • We are making a game to encourage parents and teens to talk about puberty, dating, and sex. What should this game look like? |

| • What features would be important to help parents and teens talk about dating and sex? |

The authors used thematic content analysis to code and analyze transcript data and assess content meaning.43 A codebook that compiled the themes and subthemes was developed using an iterative data analysis and team consensus process. Three qualitatively trained coders independently coded transcripts using ATLAS.ti (version 7.0.8) software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) to organize quotes and summarize themes. First-round coding was conducted using two transcripts to generate a codebook. Authors then separately coded remaining transcripts and used group consensus to facilitate agreement between coders when discrepancies occurred.

Results

Adult participants were mothers (85 percent) and fathers (15 percent) of African American (40 percent), white (45 percent), and Hispanic (15 percent) ethnicity, between 31 and 51 years of age, married (55 percent), and college graduates (65 percent). The majority of youth were female (68 percent), 11–14 years of age (mean=12 years; standard deviation=0.276 years), and with similar ethnic identity as their parents (47 percent African American, 42 percent white, and 11 percent Hispanic). When asked about their perspectives on an intergenerational sex education game, six themes emerged (described below).

Parents and youth regard sexual health and communication as important

Parents regarded sexual health as an important preparation for life, stating that “When they are out of your control [youth] have to be ready for the things that they are going to face” [Mother 5], while providing a caution: “… it is important information, and we don't want it trivialized…you have to be careful with the term ‘game’” [Mother 6]. Parent–child communication was regarded as a central component for a sexual health game: “… it's all about the conversation…you need to create something where parents are going to bring it to their kids and say, ‘Look. I think this is cool…I want you to do this with me for a little bit,’ and it starts the conversation” [Father 3]. Parents and youth reacted positively to the idea of a sexual health education game as a mediator of communication.

Parents want to be a focal part of their child's sexual health education

Parents wanted to be engaged, stating that “I really make it a point to try to explain it to her…even if I don't feel comfortable…because I prefer her to hear it from me than incorrectly from someone else” [Mother 9] and “… to hear it from mama first as opposed to getting wrong information from your friends” [Mother 10]. Thoughts on gameplay included inputting the parent as a game partner, as well as the dynamic of shared communication and discovery including a parental gate-keeping role to the youth's game progress (Table 2, perspectives A and B). Parents and youth recommended that sexual health skill-building topics be embedded in gameplay, including parent–child communication, negotiation and decision making, puberty, sexual behavior, and STIs. However, parents recommended providing parent controls over the sexual health content so they could have discretion over the delivery of more mature content (e.g., sexual risk reduction) (Table 2, perspective C) and have the game reflect their particular family and personal values (Table 2, perspective D).

Table 2.

Parent and Youth Perspectives

| Perspective | Sample quotes |

|---|---|

| Parents want to be a focal part of their child's sexual health education | |

| A. Parent as game partner | “… it would be nice at the beginning if you could input…‘Who are you doing this program with?’ And then it could take that and put it in, you know, like as you go along. So every time it would say, ‘Your parent.’” [Mother 5] |

| “I would want to be there with her to talk about STDs so that we can go in detail…as we push buttons it gives us information more about the STD so we can talk about it, it would be a great way…to lead into talking about it, then it's like we could both be learning at the same time and yet we can use that top stimulate a conversation. ‘Oh, look what it says here.’ ‘Okay, look what happens because of this.’ And then, at the same time, that stimulates us talking about it.” [Mother 9] | |

| B. Parent as gatekeeper in gameplay | “… and I think that's a huge component that will be needed— maybe that's how they unlock stuff. Maybe after this conversation, your mom or dad, they have the code.” [Mother 1] |

| “It's very short, less than 10 questions. Now you guys answer those together and then, and maybe the parent has a code or whatever where they're able to put in to answer those questions so, it really is a parent. And then they're able to go on to the next level. That didn't take any of my time, but that did lead into a conversation…and then they'll say, okay, based on your child's score or based on your score, whatever, these are the talking points.” [Mother 1] | |

| “I need to ask my mom or dad or whomever this question or whatever and now I can put in the answer, get the code, and then move on to the next level with my parent…guide them…building that bridge” [Mother 1] | |

| C. Parent as gatekeeper of content | “… there may be a way to…differentiate the topics for your child if they're not ready for it. And before you go on to level two your guardian has to come in and complete their step before level two is obtained.” [Mother 6] |

| “You can check off I want weekly updates or I want to enter a password for the—yeah, [parental controls] would be a great idea.” [Father 1] | |

| D. Parent input on family values | “… there is also a customizable part for the parent, that somehow our family values are included. Parent will have to input, you know, family of four…religious values or what have you before it is installed on your computer or your phone …” [Mother 5] |

| “… what about the morality issues? Are you going to have like contraception and, you know, you get into all those cultural differences and gay and lesbian sex or, is that going to be on there? I mean I think those need to be a part and maybe that could be—could be—if the parents get notification.” [Mother 2] | |

| Parents and youth want to be better at initiating the conversation | |

| E. Game cues for youth to engage parents | “… they made this decision in the game, which could lead to this conversation…here are some options or suggestions based on their level that they went to, question topics to talk about…it also has to do with parents, decisions parents make, the conversations we choose to have and choose not to have…if we had maybe other conversations this path wouldn't have happened…I think maybe that's a way [to] pull the parent back into the game and make the kid say, mom, I need you to get on the game because I need you to answer this so I can go on with my journey” [Mother 3] |

| “I think at some point, the computer would have to say, ‘You need to talk about this with your parent,’ and not just be going through the game. Because the computer is not a real person. It's just not” [Son 2] | |

| “I think you should have a lesson on communicating with your parents about dating and…puberty. You should have stuff…to let you know to talk to them. Because you can't just go up to your parents—it might feel kind of weird going up to your parents and saying, ‘I want to talk about dating’…it might be kind of awkward…” [Daughter 1] | |

| Parents want to be a credible resource for their youth | |

| F. Parental resources | “There does need to be quite a section for the adults to not only view the educational part that [their children] are seeing but to maybe expand a little…put a little background…because, boy they ask a lot of questions, because the things they're hearing is different, you know?…what these words mean, and what they mean to other teens—right?” [Mother 5] |

| “… there should be resources or places to go to …to get more information…is there a clinic that passes out condoms?…where can you go in your city to get condoms?” [Mother 6] | |

| “That was an excellent idea to have some kind of resource for the parent so let them know…if they're…at this point in the game, this is what it's teaching them. And so that way, whenever they come and say, well, you know, I was just playing the game, and it said this. Then you have your little instruction guide or something like that that you can say, okay, this is what it was talking about. And then, you know, from a parent—from that standpoint, you'll be able to know what it is to explain to them” [Father 2] | |

| G. Advanced content cues | “Or just to have an understanding of what it is that you're trying [to do]. And then let me use it so that I could see it first, and then I would probably be more open and willing to say, ‘Okay, let's try this together’ because I know what it's about, I have seen it before, and I feel more confident about doing this with my student [student ?]. Because if I go into something and I don't know exactly what it's about and I'm sitting there with him—especially on the subject of sex—I'm going to be a little probably intimidated or a little unsure of—what if it asked him a question and I don't have the answer?… if I don't have an answer for what chlamydia or gonorrhea is—if I didn't know that…I would like to know that information ahead of time because I want to be the person that my child goes to for those answers, and I'll be the first one to admit I don't have all the answers” [Mother 7] |

| Parents and youth want to keep the conversation going | |

| H. Parent scaffolding | “… we can get an email saying …your child understands this but his low points are this. You may want to discuss this with your child. At least you know where they're at. You can do like key points on what you can talk to your kids about, like give some kind of email thing to where you know what to do with them.” [Mother 4] |

| “… where the parents get the updates and all that, it's, that's one of the things I love is like both my kids' computers that they have” [Father 1] | |

| “… the student do[es] a portion of it and then the parent could come back with them and go over that topic and hopefully allow them to have some sharing and some discussion…the game will be fun and interactive because kids like those things. And then it could be where the parent comes in and talks with them about it and shares during that time, and that's a way for them to bond on it.” [Mother 7] | |

| I. Increasing the comfort for future discussion | “Like as you go along—like in the beginning you can start talking about dating, then you can talk about puberty, then as it goes on—. And like sex is one of the higher ones or like STD's, things like that. So you can start with the stuff that's not very awkward. Then as you go along, get more awkward, then you're more comfortable talking to your parents about it. So when it ends…you're now more comfortable than you were before with your parents. So you don't feel uncomfortable just talking to them.” [Son 1] |

| “It's important to talk to your parents throughout the game, because…when all the lessons are over and you already learned about everything, then what else are you going to do now?…You have to be able to talk to your parents about anything” [Daughter 1] | |

| J. Scheduling challenges | “During the school year, with my schedule…I don't have time to double check…we need to take that into consideration …. we need to think about those parents who have the jobs, who have 5 kids they're juggling” [Mother 1] |

| “They're working 2 jobs, 3 jobs, 1 job, whatever. They come home. Even those—my kids have a 2-parent home, but I come home. I'm like, look. I don't even want to help you with your real homework let alone a game, so just doing something, you know, that's quick and in and out or whatever” [Mother 1] | |

| “Because my parents are busy. I have two younger siblings. So they're not going to have time to sit down at the computer and play a game with me, that's just not how it works.” [Son 1] | |

| K. Play at a distance | “She is on her phone and you don't even have to be in the same room with each other at the same time, and I think that's the part that's kind of interesting for her …technically you can hear each other. You're on the phone. And the tic-tac-toe screen comes up on both of your phones, and you're marking, and you have to wait for the other person to mark, but she's the other person. So you're playing the game back and forth and you're talking at the same time she likes that” [Mother 9] |

| L. Pause points | “You finished it, but there are probably some things you could go back and refresh yourself on” [Mother 6] |

| “… to be able to pause it and…and then come back.” [Daughter 4] | |

| Parents and youth want a fun, educational, and customizable game experience | |

| M. Player choices affecting future consequences | “I like it that… making right decisions in your life makes you a hero, and you are in control of the choices and decisions you make. That does outline the path of your journey in life.” [Mother 8] |

| “…it's like a reflection at the end of the game, the choices that you make, they tell you like a reflection. They tell you what you did right and how you could—if you wouldn't have done it, how you would have ended up…you might not plan to get pregnant, you might not plan to catch things, but things happen. So you always have to be sure that you know what you're doing and that you are being smart with the decisions that you make.” [Daughter 2] | |

| “… unlock and the true destiny begins to be revealed. That could connect to…the health/sex thing, like it will help people better understand and reveal things that they might not feel comfortable about explaining and talking about. But it will help you in the long run though, and turn your future into something brighter” [Daughter 2] | |

| N. Testing achievement | “Pretty much nowadays, that's the big thing with almost any game is an achievement.” [Father 1] |

| “Like maybe if you were fighting with another character and you were to win, you would get a card and you can collect all these cards and then battle, like a big one.” [Daughter 4] | |

| O. Nondidactic learning | “So it doesn't feel like school. Because I know that kids aren't going to want to play something that's like school. So if they're moving along and they have questions asked, if it's just like natural questions that make sense in the situation, then it wouldn't, then it would make more sense.” [Son 2] |

| “So it's about expressing yourself so you can have fun while playing the game while you're learning about healthy relationships.” [Daughter 1] | |

| P. Customizable avatars | “Customization…he likes to [have] his character…look like the way he wants them to look.” [Father 2] |

| “I like the designing your character stuff. Makes it fun.” [Daughter 3] | |

STD, sexually transmitted disease.

Parents and youth want to be better at initiating the conversation

Parents and youth reported the potential for discomfort and uncertainty in discussions involving sex, suggesting that “… parents don't quite know how to approach the conversation” [Mother 11] and citing difficulties in that “some parents don't talk about it at all, don't want to talk about it at all,…are scared of it [and] others are ‘figure it out on your own’” [Mother 7] or, conversely, that “… a parent that attacks it too aggressively…can turn a child off from the conversation and all they hear is wah-wah-wah…” [Mother 11].

Parents perceived their youth as being uncomfortable discussing sex with them, and parents were uncertain about when to discuss sex and the messages they should be communicating, saying “she's [my daughter's] not comfortable with it yet, so then my question becomes am I saying it too soon, but then I don't want to not say it and then—you know. I don't want to stress her out, but at the same time I notice that if I say the word she's like, ‘Ahhhh!’” [Mother 9]. Youth echoed their parent's perceptions of discomfort: “… [it's] awkward for the kid to be the one to start the conversation with the parents” [Daughter 3]. Many parents lacked role models for parent–youth communication about sex when they were young, increasing their uncertainty about how to have the conversation: “… it's [a discussion] that I don't want to have with her…looking at my own experience, I look at her and I look at my mom and the talks we had…she never really talked about it” [Mother 9].

Parents and youth reported the connection experienced when playing games together, motivated by bonding around the shared gaming experience: “I think just being together, and having fun and laughing, and trying to figure out the answer in the time, and being silly…just that interaction together” [Mother 8]. This dynamic segued to more meaningful conversations: “I like the dynamic of being together to play because I think then it opens up more genuine conversations and sharing…to show that it is real. It's not just something that you see or know on TV” [Mother 8]. It also offers common ground: “I try to make him feel comfortable with me, to talk to me…I try to talk to my son and tell him, you know, it's okay. Mommy knows you're talking to her. And try to make him feel comfortable, but he still won't act like he's interested. So the game for me would be great” [Mother 12].

Parents and youth saw a game as a means of empowering youth to engage parents: “You're going to them [parents] instead of them coming to you, making you feel uncomfortable (like them just coming up to you like, ‘Hey, want to talk about sex?,’ that's kind of like weird)” [Daughter 2]. Youth described how communication could transition from text to face-to-face: “… you are playing the game with your parents…you're asking them a question and they answer back…‘Are you comfortable with this?’…then you should probably decide to come together and have a talk about it. Not on the computer, not typing, like a real conversation…then you can be rewarded for that” [Daughter 1]. Parents described that “the draw to some of those games is the fact that you are doing it separately so you [have] a way to leave questions…or you get to a point and it says, ‘Go talk to your mom now’” [Mother 10]. Parents and youth endorsed texting features to increase their comfort and as a way to start conversations: “… if I have something that I think would be awkward…I think it's easier to text the other person” [Daughter 5] or “most teens like to text, and they have fun texting” [Daughter 4]. Parents and youth described how a game could cue this process (Table 2, perspective E). Parents described the value of game-initiated conversation starters and guides: “it would [be] nice to have something that…leads you along the way, it's an awkward talk to start…that would be useful” [Mother 8] or “… I would get an email saying here's some things to start a conversation” [Mother 2].

Parents want to be a credible resource for their youth

Parents expressed concerns about being a credible resource and their need for support: “I'm relying on this program…to help my student succeed and for me to not feel intimidated or that I don't have… the answers, but I can go to a place to get the answer” [Mother 7]. Parents suggested providing supporting resources (Table 2, perspective F) and advanced cues (Table 2, perspective G) to allow review of pending content to prepare them for conversations that would be easy, nonintensive, and self-directed and provide resources to boost their knowledge and skills (including “Ask An Expert,” “Frequently Asked Questions,” and “Information Guides and Links”).

Parents and youth want to keep the conversation going

Parents described game scaffolding including prompts, updates, guidance through communication activities, and action cues to maintain the conversation dynamic and bonding (Table 2, perspective H). Youth described progressing gradually in their discussions from less to more mature content to allow for increased familiarity and comfort with the content, enabling future conversations following game completion (Table 2, perspective I).

Parents and youth reported that the circumstances for sexual health communication were more commonly spontaneous or opportunistic interactions rather than formalized, often in a “nonconfrontational” space such as the car, euphemistically described as the “new dining room table.” Time constraints were consistently cited as the barrier to parent involvement in communication and gaming: “There's times during the school year—you're running with your kids. You're working that full-time job. You don't have time. …” [Mother 13] (Table 2, perspective J). Recommendations to accommodate busy lifestyles included dyadic play at distance (Table 2, perspective K), the ability to pause gameplay (Table 2, perspective L), and the use of smartphones as a preferred platform: “… everything is through the cell phone now” [Mother 14]. Gaming frequently occurred in the car: “You sit in the car a lot waiting for them to come out of whatever activity they are in, and it is just right there […] you can entertain yourself” [Mother 2].

Parents and youth want a fun, educational, and customizable game experience

Parents and youth described learning about sexual health in terms of life choices and consequences, suggesting the importance of taking control of one's life and making smart decisions (Table 2, perspective M) with embedded learning assessments that linked to game achievement (Table 2, perspective N). Youth recommended these assessments be engaging (e.g., puzzles, battles, and transit through adventure levels) and rewarded by cards, coins, coupons, and next level “unlocks.” Future consequences were exemplified as a fluid indicator of achievement: “… if you're doing badly, the setting changes to dark future, and [if] you're doing good it changes to good future” [Daughter 3]. Recommended game features included distinct competitive gaming levels that are brief (under 45 minutes) with learning opportunities that are nondidactic and a natural component of gaming fun (Table 2, perspective O).

Parents and youth preferred an animated look and feel to characters and situations that approximated realism but were not too “cartoony” and preferred realistic interstitials (compared with a fantasy or futuristic layout) and customizable avatars (Table 2, perspective P). Of the presented story exemplars, a “mystery” plotline was most positively received: “It's suspenseful…you know after you're done with the story there's going to be a big secret at the end. So it makes someone want to finish it” [Son 1]. Parents and youth recommended the need to accommodate gender preferences in gaming (which parents perceived as substantially divergent), with relative gaming inclinations of girls toward “nurturing” and boys toward “adventure.”

Data synthesis

The data were synthesized into a features inventory and conceptual framework to inform developers and researchers with a high-level summary of parent and youth perspectives on desired game specifications.

The Game Features Inventory (Table 3) is a synthesis of perspectives on IGG educational content, learning strategies, and gaming strategies. Game preferences supported the use of an immersive approach with engaging story narratives, fantasy elements, and interactive features that offer meaningful feedback and rewards that are also associated with positive outcomes. Recommendations included explicit goals, scoring, audiovisual effects, customizable avatar characters, speaking characters, attention to gender relevance, realistic sound, graphics, and setting, and the beliefs, norms, needs, and behaviors of the target audience. Other recommendations were more specific to the intricacies of the sexual health domain and the accompanying communication and cultural challenges. These included defined sexual health content, progressive delivery and discussion of topics from less to more mature content over the course of gameplay, communication guidance and resources, and reflection of family values.

Table 3.

Game Features Inventory

| Educational content and learning strategies |

| • Sexual health skills-building content embedded in gameplay: puberty, sexual behaviors, STIs, negotiation and decision-making skills, and parent–child communication skills |

| • Progress from topics that have less “mature” content (e.g., healthy friendships) to topics with more “mature” content (e.g., sexual risk reduction) |

| • Role-play simulation featuring decision making and consequences |

| • Learning assessments of achievement embedded in the game |

| • Engaging assessments represented by puzzles, battles, and transit through levels |

| • Performance-based rewards that include object bonuses, coins, gaming currency, coupons, next level “unlock” options |

| • Resource guides FAQs, ask-the-expert, information guide, and links |

| • Personalized avatars and game elements to reflect family and personal values (character traits, moral virtue) |

| Communication components |

| • Sexual health skills-building content embedded in gameplay: puberty, sexual behaviors, STIs, negotiation and decision-making skills, and parent–child communication skills |

| • Progress from topics that have less “mature” content (e.g., healthy friendships) to topics with more “mature” content (e.g., sexual risk reduction) |

| • Role-play simulation featuring decision-making and consequences |

| • Learning assessments of achievement embedded in the game |

| • Engaging assessments represented by puzzles, battles, and transit through levels |

| • Performance-based rewards that include object bonuses, coins, gaming currency, coupons, next level “unlock” options |

| • Resource guides FAQs, ask-the-expert, information guide, and links |

| • Personalized avatars and game elements to reflect family and personal values (character traits, moral virtue) |

| Gaming strategies to increase enjoyment |

| • Game levels of short duration (<45 minutes), distinct, and competitively challenging |

| • Avatars and game spaces that can be customized and personalized |

| • Tailoring avatars and game elements |

| • Pause points to save the game state |

| • Gameplay that accommodates nurturing (girls) and adventure (boys) |

| • Animated situations, characters, and setting approximating reality (but “virtual”, animated—not too “cartoony”) |

| • Suspense/adventure plot |

| Channel and setting |

| • Mobile access |

| • Universal across platform access (phones, tablets, laptops) |

| • Real-time access for engagement in any location |

| • Ease of access |

FAQ, frequently asked questions.

Although the results presented are cross-group and include the reports of both male and female parents and youth, we found no substantial gender-based differences in themes.

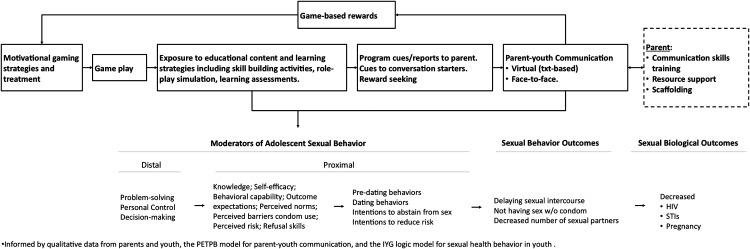

The Framework for a Sexual Health IGG (Fig. 1) provides a concept of how the expressed needs of parents to be a focal gatekeeper may be parsimoniously balanced against time burdens of gameplay. Here, updates, parallel learning opportunities, and gatekeeper communication and support enable a parent to play (and learn) in the dyad without demanding complete gameplay. The association between the game components and targeted parent and youth mediators (knowledge, beliefs, skills, and intentions of parent–youth communication and sexual behavior informed by previous models) is also exemplified.13,32–34

FIG. 1.

Conceptual framework for a sexual health intergenerational game. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IYG, Its Your Game; PETPB, Parent-based Expansion of the Theory of Planned Behavior; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

Discussion

This study provides insight into parent and youth perspectives on the use of intergenerational gaming to mediate parent–youth communication for sexual health. Parents and youth affirmed that a game could offer a neutral point of shared inquiry that can be appealing to youth and supportive of parents without necessarily being burdensome. These findings support many features that have become normative in gaming and provide a reminder of the importance of involving end-users in game design as well as formative evaluation.44 A critical design challenge is the involvement of parents who are necessarily overcommitted (echoing previous barriers to conventional, multisession sex educational programs). An apparent paradox is how to accommodate mobile platforms and flexible communication modalities (text and face-to-face) while aiming to strengthen the parent–youth bonding experience using a shared educational gaming journey. Parent and youth perspectives were largely complementary in terms of the challenges to communication, importance of parent and youth discussions, and considerations of “look, feel, and function.”

The conceptual framework and inventory of game design preferences provide developers and researchers with a distillation of high-level parent and youth perspectives on desired game specifications. Results are consistent with previously reported youth preferences regarding goals, scoring, audiovisual effects, user-developed avatars,44 attention to gender relevance,26,45,46 realism,47 and salience to the attitudes and behaviors of players.17 Random elements and sufficiently quick system response times have been cited in previous studies but were not mentioned by current respondents.48

Several limitations should be noted, including the collaboration of a small, self-selected sample of parents and youth who were likely more disposed to discussing gaming and sexual health topics than the general population, and the limitations of the prompts and exemplars used to gather information. Despite the small sample size, no new themes emerged after several focus groups and final groups confirmed those themes. In alignment with other parent-involved studies, there was low participation of fathers.49 No specific efforts were made to increase the participation of fathers. We allowed families to self-select who would be most involved in sexual health education. Additionally, we did not cross-analyze gender-related differences between gender-discordant dyads. However, study findings can be considered a valuable voicing of preferences of those parents and youth most likely to use an IGG for sexual health.

An intergenerational sexual health education game designed to address user preferences may impact communication by providing parental input into customization, timely content delivery, parsimonious resources, and guidance in support of the parent–youth discussion. Enhanced quantity and quality of communication may mediate improved sexual health outcomes beyond those reported with traditional sexual health education focused only on youth. Targeting parent and youth communication self-efficacy and skills, increasing parent knowledge to field sexual health questions, and enabling communication by “hardwiring” discussion into the game dynamic may overcome critical communication barriers.13 This study is the first to our knowledge to gather parent and youth perspectives on the importance, design, and function of an intergenerational sexual health education game to engage parents and youth to communicate about sexual health and reduce youth sexual risk behaviors. Results of this study will inform the development of an intergenerational sexual health education game and may have utility for those designing and implementing serious games for sexual health.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 1R42HD074324-01 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Kost K, Henshaw S. US Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortions, 2010: National and State Trends by Age, Race and Ethnicity. www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrendsstate10.pdf.2014 (accessed June, 15, 2014)

- 2.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ 2014; 63(Suppl 4):1–168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landry DJ, Singh S, Darroch JE. Sexuality education in fifth and sixth grades in US public schools, 1999. Fam Plann Perspect 2000; 32:212–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller TE, Gavin LE, Kulkarni A. The association between sex education and youth's engagement in sexual intercourse, age at first intercourse, and birth control use at first sex. J Adolesc Health 2008; 42:89–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirby D. The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual behavior. J Sex Res 2002; 39:27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirby D, Lepore G. Sexual Risk and Protective Factors: Factors Affecting Teen Sexual Behavior, Pregnancy, Childbearing, and Sexually Transmitted Disease: Which Are Important? Which Can You Change? Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, ETR Associates; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA 1997; 278:823–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sieving RE, McNeely CS, Blum RW. Maternal expectations, mother-child connectedness, and adolescent sexual debut. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000; 154:809–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borawski EA, Ievers-Landis CE, Lovegreen LD, Trapl ES. Parental monitoring, negotiated unsupervised time, and parental trust: The role of perceived parenting practices in adolescent health risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health 2003; 33:60–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen DA, Farley TA, Taylor SN, et al. When and where do youths have sex? The potential role of adult supervision. Pediatrics 2002; 110:e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeely C, Shew ML, Beuhring T, et al. Mothers' influence on the timing of first sex among 14-and 15-year-olds. J Adolesc Health 2002; 31:256–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beckett MK, Elliott MN, Martino S, et al. Timing of parent and child communication about sexuality relative to children's sexual behaviors. Pediatrics 2010; 125:34–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchinson MK, Wood EB. Reconceptualizing adolescent sexual risk in a parent‐based expansion of the theory of planned behavior. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007; 39:141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villarruel AM, Loveland‐Cherry CJ, Ronis DL. Testing the efficacy of a computer‐based parent‐adolescent sexual communication intervention for Latino parents. Fam Relat 2010; 59:533–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turnbull T, van Schaik P, Van Wersch A. Exploring the role of computers in sex and relationship education within British families. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2013; 16:309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lustria MLA, Cortese J, Noar SM, Glueckauf RL. Computer-tailored health interventions delivered over the Web: Review and analysis of key components. Patient Educ Counsel 2009; 74:156–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pappa D, Dunwell I, Protopsaltis A, et al. Game-based learning for knowledge sharing and transfer: The e-VITA approach for intergenerational learning. In: Felicia P, ed. Handbook of Research on Improving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games: Multidisciplinary Approaches. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; 2011: 974–1003 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S-J, Chae Y-G. Children's internet use in a family context: Influence on family relationships and parental mediation. Cyberpsychol Behav 2007; 10:640–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin EW. Exploring the effects of active parental mediation of television content. J Broadcast Electron Media 1993; 37:147–158 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gentile DA, Reimer RA, Nathanson AI, et al. Protective effects of parental monitoring of children's media use: A prospective study. JAMA Pediatr 2014; 168:479–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radanielina-Hita ML. Parental mediation of media messages does matter: More interaction about objectionable content is associated with emerging adults' sexual attitudes and behaviors. Health Commun 2014. August 30 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.900527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akers AY, Holland CL, Bost J. Interventions to improve parental communication about sex: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2011; 127:494–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burrus B, Leeks KD, Sipe TA, et al. Person-to-person interventions targeted to parents and other caregivers to improve adolescent health: A Community Guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2012; 42:316–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wight D, Fullerton D. A review of interventions with parents to promote the sexual health of their children. J Adolesc Health 2013; 52:4–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Downing J, Jones L, Bates G, et al. A systematic review of parent and family-based intervention effectiveness on sexual outcomes in young people. Health Educ Res 2011; 26:808–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guilamo-Ramos V, Lee JJ, Kantor LM, et al. Potential for using online and mobile education with parents and adolescents to impact sexual and reproductive health. Prev Sci 2015; 16:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ito M, Baumer S, Bittanti M, Boyd D, Cody R, Herr-Stephenson B, Horst HA, Lange PG, Mahendran D, Martínez KZ, Pascoe CJ, Perkel D, Robinson L, Sims C, Tripp L. Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out: Kids Living and Learning with New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans AE, Edmundson-Drane EW, Harris KK. Computer-assisted instruction: An effective instructional method for HIV prevention education? J Adolesc Health 2000; 26:244–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiene SM, Barta WD. A brief individualized computer-delivered sexual risk reduction intervention increases HIV/AIDS preventive behavior. J Adolesc Health 2006; 39:404–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirby D. Innovative Approaches to Increase Parent-Child Communication About Sexuality: Their Impact and Examples from the Field. New York: Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paperny DM, Starn JR. Adolescent pregnancy prevention by health education computer games: Computer-assisted instruction of knowledge and attitudes. Pediatrics 1989; 83:742–752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Peskin MF, et al. It's Your Game: Keep It Real: Delaying sexual behavior with an effective middle school program. J Adolesc Health 2010; 46:169–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markham CM, Tortolero SR, Peskin MF, et al. Sexual risk avoidance and sexual risk reduction interventions for middle school youth: A randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health 2012; 50:279–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shegog R, Peskin MF, Markham CM, et al. ‘It's Your Game-Tech’: Toward sexual health in the digital age. Creative Educ 2014; 5(Special Edition):1428–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voida A, Greenberg S. Collocated intergenerational console gaming. Universal Access in the Information Society. Research Report 2009-932-11, 2009; 1–24 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voida A, Greenberg S. Console gaming across generations: Exploring intergenerational interactions in collocated console gaming. Universal Access Inform Soc 2012; 11:45–56 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derboven J, Van Gils M, De Grooff D. Designing for collaboration: A study in intergenerational social game design. Universal Access Inform Soc 2012; 11:57–65 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Y, Wen J, Xie B. “I communicate with my children in the game”: Mediated intergenerational family relationships through a social networking game. J Community Inform 2012; 8:1 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiong C. Can video games promote intergenerational play and literacy learning. Paper presented at The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop, New York, July30, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Othlinghaus J, Gerling KM, Masuch M. Intergenerational play: Exploring the needs of children and elderly. Paper presented at Mensch & Computer Workshopband, Chemnitz, Germany, September11–14, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rice M, Tan WP, Ong J, et al. The dynamics of younger and older adult's paired behavior when playing an interactive silhouette game. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, Paris, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krueger RA. Moderating Focus Groups, Vol. 4 Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trepte S, Reinecke L. Avatar creation and video game enjoyment: Effects of life-satisfaction, game competitiveness, and identification with the avatar. J Media Psychol 2010; 22:171 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baranowski T, Buday R, Thompson DI, Baranowski J. Playing for real: Video games and stories for health-related behavior change. Am J Prev Med 2008; 34:74–82.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dickey MD. Engaging by design: How engagement strategies in popular computer and video games can inform instructional design. Educ Technol Res Dev 2005; 53:67–83 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wood RT, Griffiths MD, Chappell D, Davies MN. The structural characteristics of video games: A psycho-structural analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav 2004; 7:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malone TW, Lepper MR. Making learning fun: A taxonomy of intrinsic motivations for learning. Aptitude Learning Instruction 1987; 3:223–253 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panter‐Brick C, Burgess A, Eggerman M, et al. Practitioner review: Engaging fathers—Recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014; 55:1187–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]