Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to test the feasibility and acceptability of a novel online adolescent substance abuse relapse prevention tool, “Arise” (3C Institute, Cary, NC). The program uses an innovative platform including interactive instructional segments and skill-building games to help adolescents learn and practice coping skills training strategies.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a pilot test with nine adolescents in substance abuse treatment (44 percent female) and a feasibility test with treatment providers (n=8; 50 percent female). Adolescents interacted with the program via a secure Web site for approximately 30 minutes for each of two instructional units. Treatment providers reviewed the same material at their own pace. All participants completed a questionnaire with items assessing usability, acceptability, understanding, and subjective experience of the program.

Results: Regarding feasibility, recruitment of this population within the study constraints proved challenging, but participant retention in the trial was high (no attrition). Adolescents and treatment providers completed the program with no reported problems, and overall we were able to collect data as planned. Regarding acceptability, the program received strong ratings from both adolescents and providers, who found the prototype informative, engaging, and appealing. Both groups strongly recommended continuing development.

Conclusions: We were able to deliver the intervention as intended, and acceptability ratings were high, demonstrating the feasibility and acceptability of online delivery of engaging interactive interventions. This study contributes to our understanding of how interactive technologies, including games, can be used to modify behavior in substance abuse treatment and other health areas.

Introduction

Adolescent substance abuse is a major national health concern in the United States. Approximately 157,000 adolescents receive treatment for a substance use problem each year, and this figure represents only a fraction of the estimated 1.6 million youth in need of treatment.1 Unfortunately, even with treatment, relapse is common. Six-month relapse rates typically range from 60 to 70 percent,2,3 and the likelihood of relapse increases over time.4 There clearly is a pressing need for effective relapse prevention strategies and tools for adolescents. Aftercare, which provides a bridge from the protective environment of primary care to the challenges of sobriety maintenance, has been shown to reduce relapse rates for adolescents with substance use disorders.5–8

Substance abuse aftercare and intervention vary widely in type and intensity. One of the most effective types is coping skills training (CST),9,10 the goal of which is to replace maladaptive responses with adaptive ones. CST addresses a major factor in the maintenance of addictive behavior—a lack of alternatives for coping with the events that trigger and result from substance use.11–13 Participants in CST develop specific alternative responses to events that lead to substance use, so when a relapse trigger inevitably occurs they have healthier response alternatives to substance use. CST is a proven approach consistent with a recent reconceptualization of the relapse process14 that emphasizes the multidimensional and dynamic nature of relapse. The “Arise” program (3C Institute, Cary, NC) described in this article is well suited to this model because it addresses the many factors leading to relapse events by incorporating education and practice opportunities in the interpersonal and intrapersonal cognitive and affective domains.

Researchers have suggested that increasing the number of treatment modalities would improve the success rate of adolescent substance abuse treatment.3,15 Technology-based games are a logical new modality for this population. Active participation with interactive training software has been found to dramatically increase engagement and skill development beyond more passive instructional methods (e.g., reading text, listening to a lecture).16 The hands-on experience and practice offered by digital environments can effectively support instructional objectives, particularly for more complex skills such as coping and navigation of high-risk situations.17 Furthermore, engaging multiple sensory modes (visual, auditory, experiential) during training means the software can reach different types of learners and promote greater retention and application of presented information.18,19

Although very few game-based aftercare programs are available and data from those programs are limited, preliminary findings indicate technology-based aftercare could be accepted and effective. Adolescents and substance abuse counselors have indicated strong interest in computerized relapse prevention programs,20 and treatment providers support incorporating computer-assisted intervention programs into treatment and follow-up.21 For example, a promising exploratory study into the efficacy of a virtual reality game in which participants crushed cigarettes showed gameplay led to decreased smoking and increased retention in treatment for adult smokers.22 These initial steps in research on computer game-based relapse prevention programs indicate interest in and support for this approach and point to the advisability and timeliness of developing effective technological approaches to substance abuse treatment and relapse prevention.

In this study, we report findings from a pilot test of an online program for substance abuse relapse prevention, “Arise.” A pilot study is an essential first step in exploring a novel or innovative intervention. It informs the usability and acceptability of the intervention and points to aspects that should be modified for a larger hypothesis testing study, but a pilot study is not appropriate for hypothesis testing or outcomes measurement.23 We report here on the practicality of participant recruitment and retention, as well as the feasibility of administering the intervention and outcomes assessment components using this innovative methodology.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Nine adolescents who were receiving substance abuse treatment participated in the pilot test. We recruited these adolescents in collaboration with area treatment facilities, psychological service centers, and relevant treatment specialist listservs. Participants were screened to ensure they met eligibility requirements (i.e., 15–17 years of age, met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV criteria for substance abuse/dependence preceding primary treatment, completed within the last 30 days or currently participating in substance abuse treatment, and proficient in reading and writing English). It should be noted that the initial intent was to include in the pilot test adolescents who had completed active substance abuse treatment (inpatient or outpatient) within 30 days of the pilot test period, but recruiting this sample in our very limited time window proved impracticable. As a result, our sample comprised adolescents currently in active substance abuse treatment, in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

The average age of participants was 16.3 years, and four were female. Five participants identified their race as white, and four self-identified as African American. Participants indicated their substance(s) of choice via an open-ended response item. The most frequently indicated substance was marijuana (n=8), followed by nicotine (n=7), prescription drugs (n=6; specified further as opioids [n=4], central nervous system depressants [e.g., diazepam, alpraxolam; n=4], stimulants [n=2]), alcohol (n=4), and finally other substances including “bath salts,” cocaine, heroin, “K2/spice,” “ecstacy/molly,” and “triple C.” Adolescent participants were compensated with $20 Amazon gift codes upon completion of their weekly questionnaire following interaction with “Arise.” In addition, participating treatment providers were compensated $50 per enrolled adolescent for the time needed to administer toxicology tests and report these and adverse events/serious adverse event results.

We also assessed the feasibility of the program with providers (n=8) who regularly treat adolescents for substance abuse. Providers were recruited through regional treatment facilities, psychological service centers, and relevant treatment specialist listservs. Two of these providers served adolescents who participated in the pilot test. Providers ranged in age from 28 to 50 years (mean, 38.3 years), and four were female. Six reported their race as white, one reported African American, and one reported multiracial. Years of experience with adolescent substance abuse treatment ranged from 2 to 21 years, with a mean of 8.6 years. Treatment providers were compensated for their time spent reviewing the prototype and providing feedback. Providers received a one-time Amazon gift code in the amount of $50 upon completion of their prototype review.

Precautions were taken to ensure ethical protection of human participants in the research study. The study protocol was approved by an institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Because all adolescents were under 18 years of age, we obtained their parents' written permission in addition to the adolescents' written assent. Adolescents participated anonymously because of the sensitive nature of the study and were only identified in the study by a participant number.

Prototype development and refinement

We developed a prototype with two units targeting coping skills for relaxation and substance refusal. Game details are shown in Table 1, and gameplay is described in detail below. The skills included in the prototype were carefully selected to represent coping skills in the intrapersonal and interpersonal domains as delineated in CST.9,10

Table 1.

Characteristics of a Videogame for Health: “Arise” Relapse Prevention Program Featuring “Blown Away” and “Stand Up” Games

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Overview | |

| Health topic | Adolescent substance abuse relapse prevention |

| Targeted age group | Adolescents |

| Other targeted group characteristics | Youth in substance abuse recovery |

| Short description of game idea | “Blown Away”: A relaxation game in which the player's goal is to move a balloon further by taking increasingly deep breaths “Stand Up”: A menu-driven game in which the player must choose the best way to refuse offers of illicit substances in different situations |

| Target player | Individual |

| Guiding knowledge or behavior change theory, model, or conceptual framework | Coping skills training |

| Intended health behavior changes | “Blown Away”: Choosing diaphragmatic breathing rather than substance use as a stress coping mechanism “Stand Up”: Increased skills and self-efficacy for substance refusal |

| Knowledge elements to be learned | “Blown Away”: Diaphramatic breathing technique as a healthy method of coping with stress “Stand Up”: Improving refusal responses when offered substances |

| Behavior change procedure (taken from Michie inventory) or therapeutic procedures used | Provide information about behavior–health link; provide information on consequences; provide information about others' approval; prompt barrier identification; set graded tasks; provide instruction; provide feedback on performance; prompt practice; relapse prevention; stress management; time management |

| Clinical or parental support needed? | No |

| Data shared with parent or clinician | Yes; usage data only (e.g., completion of games, active playing time) |

| Type of game | Educational |

| Story (if any) | |

| Synopsis including story arc | Not applicable |

| How the story relates to targeted behavior change | Not applicable |

| Game components | |

| Player's game goal/objective | “Blown Away”: Inflate and push a balloon as far as possible by taking and slowly releasing deep breaths “Stand Up”: Attain highest possible score by quickly choosing best responses to refuse offers of alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs in increasingly complex and pressured environments |

| Rules | “Blown Away”: Player must inflate and move a balloon. “Stand Up”: Player must select responses before the timer runs out. Points are awarded for quality and timing of response. |

| Game mechanics | “Blown Away”: Player presses up arrow for the duration of inhale and presses right arrow for the duration of exhale. Player is given feedback (time and quality of breath) upon completing each breath. “Stand Up”: Player chooses a verbal response to various offers to use illicit substances. Player is given feedback (score and response style) upon completing the game. |

| Procedures to generalize or transfer what's learned in the game to outside the game | Each game is partnered with an interactive lesson that provides information about transferring skills to real life, including required practice exercises to be completed between gameplays. |

| Virtual environment | |

| Setting | “Blown Away”: Nature scenes “Stand Up”: Various settings in the life of an adolescent (home, school, city location) |

| Avatar | |

| Characteristics | Not applicable |

| Abilities | Not applicable |

| Game platforms needed to play the game | Computer, tablet |

| Sensors used | Not applicable |

| Estimated time to play | Approximately 60 minutes, including both “Blown Away” and “Stand Up” games and their associated interactive lessons |

Our interdisciplinary team of psychologists, computer programmers, and graphic artists (team members and roles shown in Table 2) collaborated to create a fully functioning program that included interactive instructional segments for each unit along with dynamic gameplay to learn and practice each of these skills within an engaging virtual environment.

Table 2.

Game Development Roles

| Role | Individual(s) |

|---|---|

| Principal Investigator | Rebecca Polley Sanchez |

| Lead Game Designer | Chris Hehman |

| Instructional Content and Research | Chelsea M. Bartel Emily Brown Rebecca Polley Sanchez |

| Game Design, Concept Art, and Game Art | Matt Bell (“Stand Up” game) Emily Maschauer (“Blown Away” game) |

| Audio Engineer, Music, and Voice Casting | Steven Fichtel |

| Voice Actor | Melissa Kotz |

| Systems Architecture and Tools/Lead Programmer | Matt Habel |

| Quality Assurance | James Dooley |

In the relaxation lesson, adolescents completed an online survey about sources of stress in their lives by rating the stressfulness of life events and situations from among provided and self-entered options and then selecting their primary source of stress. Next, adolescents learned about what stress is and how it affects the body and mind. Then, adolescents answered questions to gauge their understanding of what they learned to that point. The lesson then addressed why stress can be a risk factor for relapse and introduced a healthy alternative for coping with stress: Progressive muscle relaxation. The program walked participants through a progressive muscle relaxation exercise step by step. To measure the impact of the exercise on their stress level, adolescents rated their stress level immediately before and after practicing progressive muscle relaxation.

As a final step in the relaxation unit, participants played the “Blown Away” game, which taught another proven healthy stress reduction tool, diaphragmatic breathing. The purpose of the game is to move a series of balloons across the screen while breathing deeply from the diaphragm; “better” (i.e., deeper and slower) breaths move the balloon further. To practice this skill, participants press and hold the “up” arrow as they inhale and press and hold the “right” arrow as they exhale. Relaxing music plays in the background, while, to create relaxing variation in the gaming environment, movement through time and space is simulated; the background scenery changes to represent a trip across the United States, and time of day appears to progress from morning to night. Feedback on the duration of each breath is provided to the player during the game. If the breath is a good example of diaphragmatic breathing, a “praise phrase” (e.g., Excellent breath!) is presented on screen; otherwise, the player is given feedback for improvement (e.g., Breathe deeper). Consistent with traditional diaphragmatic breathing instruction, the “Blown Away” prototype game was 10 minutes in duration.

At the completion of the game, the participant was shown a line graph indicating his or her performance over time. Ideally, the graph showed that breathing slowed over time as the participant became better at diaphragmatic breathing. Finally, participants were instructed to practice and apply the relaxation skills they learned in the lesson and game over the following week in order to encourage transfer of learned material. Participants completed a multiple choice question to indicate how many times they would practice progressive muscle relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing over the week, as well as a short answer question to identify potential barriers to practicing the skill and how they planned to address those barriers.

In the refusal skills lesson, adolescents learned about turning down offers to use illicit substances in a quick, clear, and firm manner, as well as the importance of developing and practicing specific refusal skills until they become automatic responses in times of stress. Participants determined which situations were most likely to lead to substance use for them by completing an online version of the Locations and Situation card sort activity from the Comprehensive Drinker Profile,24 identifying and rank-ordering locations and situations in which they experienced an increase risk of substance relapse. Next, they learned five specific refusal techniques: (a) refuse clearly and directly, (b) shift the conversation to a different topic, (c) suggest an alternative activity incompatible with substance use, (d) cut off the person making the offer, and (e) avoid excuses whenever possible. Then, they rated pictures of other adolescents for assertive versus passive body language, completed open-ended, timed writing exercises to generate ideas for conversation topics and other activities incompatible with substance use, created personal response phrases for direct refusal of substances, and rated the quality of provided refusal phrases from worst (e.g., excuses) to best (e.g., assertive refusal).

Following the interactive lesson, participants played the “Stand Up” game for approximately 10 minutes. “Stand Up” is a first-person game in which the player experiences several settings and situations common to adolescents (a school commons area, at home after school, and out with friends in the evening). In each situation, the player is repeatedly offered substances by various others. The goal is to select an appropriate refusal from among several presented options. More points are given for better responses, and the difficulty level increases as the game progresses (e.g., the setting is more conducive to substance use, the player's relationship with the offeror makes it harder to refuse, offerors become increasingly reluctant to accept excuses, best response options disappear after a few seconds to stress the idea of quickly providing a good refusal). After each of three scenes, the player is shown his or her score for that section. At the end of the game, the player is shown the overall game score, as well as the distribution of the types of refusals that he or she chose. This feedback is given to inform the participant of individual response style to increase the likelihood of transfer of learned skills to real world situations.

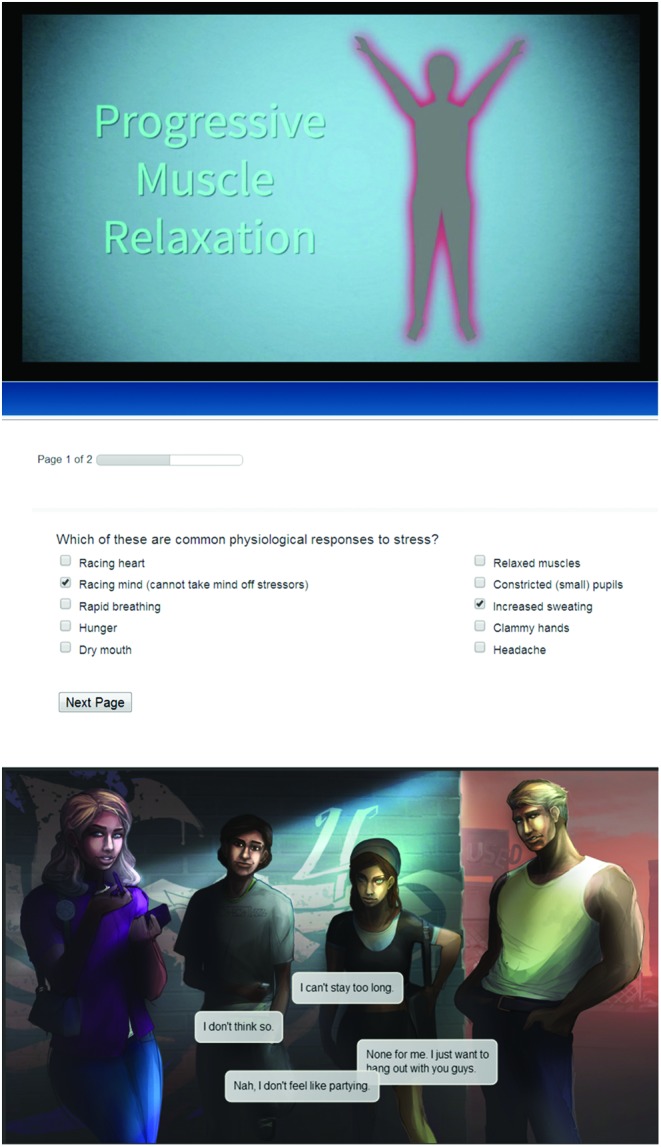

Visual images from the “Arise” program are shown in Figure 1. All dialogue included voiceover, and because the prototype was delivered online, we also created a welcome and instruction video to convey the purpose and method of the study. We built the prototype on HTML 5 standards for mobile, PC Web browser, and tablet platforms. The software is accessible through any HTML 5 Web browser with no additional software, hardware, or technical expertise needed. All components underwent rigorous quality assurance testing before release to participants. A demonstration video of the prototype can be accessed at www.3cisd.com/Arise-video.

FIG. 1.

Visual images from “Arise.” Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/g4h

As part of our iterative development process, we sent the initial prototype to our five-member consultant board, which comprised experts in adolescent substance abuse treatment. Consultants reviewed the prototype online and provided ratings, comments, and suggestions regarding usability, feasibility, content, and future development. All consultants agreed or strongly agreed that the content of the lessons and games reflected current research on relapse prevention and that the program was of high overall quality, was likely to be effective, and would be useful in a clinical setting and recommended continued development.

Based on consultant feedback, we made the following changes to the prototype prior to feasibility and usability testing with adolescents and providers:

• edited text to a reading level at or below eighth grade

• modified lessons to appeal to adolescents at diverse levels of socioeconomic status

• modified lessons to reduce the focus on academics and school-related activities as options to avoid substances

• increased racial diversity in the interactive lessons

• created a tutorial on game mechanics

• included additional examples of substance refusal statements.

Pilot test

Adolescents reviewed the prototype online over a 5-week period. Participants in the outpatient setting interacted with the prototype from home, whereas those in the inpatient setting completed the program in a small computer lab with private individual cubicles. Before interacting with the prototype, adolescents watched the video segment explaining the study and completed a demographics questionnaire (e.g., age, sex, racial and ethnic identity) anonymously via our secure online reporting system. Adolescents interacted with the prototype at the rate of one instructional unit per week, and following each weekly gameplay they completed surveys on treatment engagement and acceptability of the program. Acceptability and usability were assessed via a 13-item survey with a 5-point Likert-type scale adapted from similar measures, including the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire25 and Davis's questionnaire26 designed to assess ease of use, perceived usefulness, and attitude toward using substances.

Other questionnaires and urinalysis

In addition to the feasibility and usability measures noted above, we also included outcome measures (self-efficacy, self-reported substance cravings and use, and toxicology results) in the pilot test in order to inform feasibility and identify any modifications needed for the larger hypothesis testing study to follow. As recommended by Leon et al.,23 we did not conduct hypothesis testing or analyze the results of the outcome measures in the pilot study, as such analyses can lead to inappropriate conclusions because of small sample size and feasibility study intent.

Feasibility test

Treatment providers reviewed the prototype online over a 2-week period. They completed surveys on clarity and ease of use, innovation, value and need, potential effectiveness for achieving intended goals, usability, advantages over existing methods, and overall quality. Providers' usability and acceptability measures were similar to those of adolescents and were based on the same source instruments.25,26 Providers also rated the degree to which they would recommend the intervention to other professionals, would use/buy it themselves, believe it would be effective for enhancing relapse prevention skills, and recommend continued development and testing.

Results

Participant recruitment and retention

Initial recruitment for this study proved difficult because of the short time frame (dictated by the funding contract) and narrow inclusion criteria. Because of study design and time constraints, we were unable to take advantage of rolling enrollment, which would have eased the pressure of this requirement. The initial plan to include only adolescents who had completed active substance abuse treatment within 30 days of the start of the pilot test period proved impracticable, and we expanded our population to include adolescents who were currently in active treatment. Once we expanded inclusion criteria in this way, recruitment and enrollment were swift.

An additional challenge in recruitment was the requirement due to the sensitive nature of the data being collected that adolescent participants remain anonymous. This limited our ability to reach out to potential participants directly. In order to maintain their anonymity, participants were recruited through substance abuse treatment providers and contacted by research staff via newly created anonymous e-mail accounts and phone to discuss the study. We found that provider buy-in was essential to participant recruitment and retention, as treatment providers were actively involved in the study in terms of conducting the weekly toxicology and adverse events screenings and communicating with the research coordinators. Once we established relationships with treatment providers and they described the study requirements to potential participants (using a script and information packet we provided), we easily achieved our pilot test enrollment of nine adolescents, and no participant dropped out of the study over the course of the trial. However, one adolescent failed to submit the third urine sample for toxicology screening, and seven adolescents did not submit the fourth (final) sample.

Product testing

All usability and acceptability ratings were provided on a 5-point Likert-type scale in which 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree. Adolescents and providers rated individual items within a category, and for the sake of parsimony, mean scores and standard deviations for each category across all participants are reported in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Adolescents' Ratings of the “Arise” Prototype

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Overall prototype | |

| Usability | 4.4 (0.65) |

| Acceptability | 4.0 (0.63) |

| Perceived utility | |

| Instructional value | 4.0 (0.96) |

| Peer recommendation | 4.0 (0.76) |

| Desire for additional topics | 4.0 (0.90) |

| Continued development | 4.0 (0.90) |

| Relaxation unit | |

| Liked the lesson | 4.0 (0.87) |

| Understood the lesson | 4.1 (1.05) |

| Learned about skills in the lesson | 4.0 (1.00) |

| Liked art/graphics in the lesson | 4.2 (0.83) |

| Liked the game | 3.2 (1.20) |

| Understood the game | 4.2 (0.97) |

| Game helped develop relaxation skills | 3.8 (1.09) |

| Liked art/graphics in the game | 4.0 (1.22) |

| Refusal unit | |

| Liked the lesson | 3.9 (1.27) |

| Understood the lesson | 4.2 (1.30) |

| Learned about skills in the lesson | 3.6 (1.33) |

| Liked art/graphics in the lesson | 4.1 (1.27) |

| Liked the game | 4.8 (0.44) |

| Understood the game | 4.8 (0.44) |

| Game helped develop substance refusal skills | 4.7 (0.71) |

| Liked art/graphics in the game | 4.9 (0.33) |

Data are mean (standard deviation) values. The 5-point Likert-type scale used was 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree.

Table 4.

Treatment Providers' Acceptability Ratings

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Usability | 4.5 (0.51) |

| Acceptability | 4.0 (0.72) |

| Perceived utility | |

| Instructional value | 4.1 (0.64) |

| Clinical value | 4.0 (0.79) |

| Continued development | 4.0 (0.93) |

Data are mean (standard deviation) values. The 5-point Likert-type scale used was 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree.

Adolescent pilot test

Adolescents' mean usability and acceptability ratings are shown in Table 3. Adolescents rated the overall prototype as well as each instructional unit for feasibility and usability. We first present overall results, followed by unit results. All mean scores for the overall prototype were 4 or higher, indicating strong support for the program among end users.

Overall usability

Adolescents rated the prototype easy to use. As further evidence that the instructions and programs functioned as intended, although participants were instructed to contact our technical support team if assistance was needed, the team did not receive any calls or e-mail requests for assistance. Analysis of timestamps on each study step revealed consistent completion times for all participants, again indicating no adolescents became confused or unable to navigate the program.

Overall acceptability

The acceptability category consisted of items assessing the extent to which adolescents thought “Arise” was fun, how much they liked it, whether it took the right amount of time to play, and whether they liked the illustrations, graphics, and overall look. Ratings for this category were consistently positive, showing the “Arise” intervention is highly acceptable to this audience.

Overall perceived utility

Perceived utility included subcategories of instructional value, peer recommendation, desire for additional topics, and recommendation for continued development. Instructional value included two items evaluating whether the adolescent learned something new from the program and whether he or she learned things that would prevent a relapse. For peer recommendation, adolescents indicated the extent to which their peers would like “Arise.” Desire for additional topics and recommendation for continued development were each assessed with a single item. Adolescents rated all subcategories 4.0 or higher, indicating they thought “Arise” would be very useful as a substance abuse relapse prevention tool.

Relaxation unit

The results for the relaxation unit were largely consistent with those for the overall prototype, with most ratings being 4.0 or higher. Adolescents liked and understood the dynamic lesson and indicated that they learned relaxation skills as a result of interacting with it. Ratings for the game were positive overall, with adolescents indicating that they understood the game, that they liked the graphics, and that it helped them develop relaxation skills. Likability of the relaxation game, “Blown Away,” was rated lower than other components of the program. Review of open-ended comments revealed that several participants suggested a shorter time to play for “Blown Away.” Resulting modifications of the prototype as part of final product development are addressed in Discussion.

Refusal unit

As with the relaxation unit, the results for the refusal unit were in line with those for the overall prototype, with most ratings at or above 4.0. Adolescents indicated that they liked and understood the refusal lesson. The rating for “learned about skills in the lesson” was somewhat lower than anticipated; resulting modifications to the final product are addressed in Discussion. The refusal game, “Stand Up,” received very high ratings of likability, usability, and utility.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were included in this pilot study to assess their feasibility rather than to assess the efficacy of the program. We found that participants were able to complete outcome measures at both pre-test and post-test with no reported problems, and timestamps indicated consistent completion time, showing that no individual struggled with outcome measure completion. No adverse events were reported for any participant throughout the course of the study. The data collection system was effective and easy for participants to use.

Recommended changes

As a final question, we asked adolescents for recommended changes to the program. Responses indicated a desire for a shortened version of the (10-minute) relaxation game, and this is something we will likely add as an option in a revised version of the program.

Provider feasibility test

Providers rated the overall prototype and responded to open-ended questions about each instructional unit. As shown in Table 4, providers gave high scores for all categories (usability, acceptability, and perceived utility). All mean ratings were 4.0 or higher, indicating strong support from treatment professionals likely to recommend or purchase the program.

Usability

The usability category consisted of items assessing clarity of instructions, ease of understanding and navigation, and user-friendliness. The high rating for this category and the fact providers did not contact our support team for assistance demonstrate that the program and approach are appropriate for this audience and do not pose barriers to use.

Acceptability

Items comprising the acceptability category assessed overall quality, visual appeal, appropriateness of time to play, and overall interaction experience. Providers gave high ratings for these items, indicating high likability for the program and approach.

Perceived utility

Perceived utility included subcategories of instructional value, clinical value, and recommendations for continued development. Instructional value was a single item assessing the extent to which providers agreed “Arise” would be an effective learning tool. Clinical value included items on whether the program would be valuable to clinicians, useful in a clinical setting, adaptable to clients' needs, cost-effective, effective as support for therapy, applicable with multiple client types, and an innovative way to support adolescents, and whether they would use it in their own practice and recommend it to other clinicians. Recommendation for continued development was assessed with a single item. Providers rated all items highly, indicating they thought “Arise” would be very useful as a substance abuse relapse prevention tool.

Recommended changes

Finally, we asked providers what changes to each unit of the program they recommend for future development. In total, six changes were suggested, centering around personalization and additional specific instructional elements. These modifications are addressed in Discussion.

Discussion

In this article, we report the usability and acceptability results of a pilot study of the “Arise” online program for adolescent substance abuse relapse prevention. We were able to deliver the intervention as intended, demonstrating the feasibility of this approach. Adolescents and treatment providers completed the program with no reported problems, and overall we were able to implement measures as planned. The program also received strong acceptability ratings from both adolescents and providers, who found the prototype informative, engaging, and appealing. Both groups strongly recommended continuing development of the program and provided important feedback for modification of the prototype. Results provide strong support for “Arise,” which is one of the first generation of computer game applications in the field of addiction treatment and relapse prevention. Lessons learned from this pilot test will inform modification of the prototype and can be used to guide the development of other games for health.

Two methodological aspects of the pilot study indicated areas for improvement. Initial recruitment proved challenging, a shared concern for testing programs with limited subpopulations. In future investigations with this group, we will modify our recruitment strategy by recruiting from a larger geographic area, partnering with substance abuse treatment facilities earlier in the planning phase, and using rolling enrollment to create a larger sample size. This strategy should lead to more successful early recruitment and reduce the possibility of selection bias associated with a non-random sample of a population.

The other methodological change noted in this pilot study regards the timing of compensation. We were initially concerned that adolescents would be reticent to submit urine samples for toxicology screening but were pleased to see the response rate on this measure was very good at the first three data collection points. At the final collection, however, seven of the nine participants failed to submit a sample to their treatment provider. We surmise that this occurred because all other data collection and participation incentives were complete prior to this sample collection. In future investigation of this and similar programs, we will modify our compensation schedule to include compensation after participants complete all aspects of data collection and suggest that other researchers follow this procedure in similar investigations.

In addition to these changes to study design, adolescent and provider ratings of the individual instructional units suggested minor modifications to the prototype to optimize learning and behavior change opportunities. In response to adolescent and provider pilot study feedback, we plan to tailor the program to specific substances of choice, include an assessment of reasons for substance use, and provide information on how to communicate with treatment providers and collaborate in care. For the relaxation unit, we will add options for gameplay duration in the relaxation unit and provide a visual demonstration of the progressive muscle relaxation technique addressed in the interactive lesson. For the refusal unit, we will increase the overt educational message in the interactive lesson to increase user understanding of refusal skill development strategies and will provide more detailed feedback regarding decision points and performance.

Limitations and future directions

The small sample size in the present study is typical for prototype testing but precludes hypothesis testing. Similarly, without a control group of adolescents who did not receive “Arise,” it is not possible to test the effectiveness of this program compared with alternative approaches. After the program is fully developed, we will conduct a trial with a much larger sample size and a wait-list control group. The design and statistical power of the follow-up study will enable us to evaluate the effectiveness of the program on outcomes of interest, including substance cravings and use as well as self-efficacy for sobriety.

An additional limitation of the current study is that although “Arise” was conceived as an aftercare program, the adolescent sample included participants who were currently receiving substance abuse treatment services. We feel confident that our data reflect opinions and usage information similar to that of recent treatment completers because of the similarities in the two groups. Youth who have recently completed treatment are likely to be motivated to maintain sobriety and eager for tools to help. In the larger study of the complete program, we will take additional steps to recruit substance abuse treatment completers into our sample, as mentioned above.

The findings from this pilot study clearly support continued development of “Arise.” Plans for future development include building on these findings to develop the full set of skill-building lessons and games. The data gathered through this study and the technical expertise gained through development of the prototype will serve as the foundation for future development. We anticipate that future units of “Arise” will include intelligent game balancing; instructional and practice opportunities will be adapted to best meet the needs of the individual user (e.g., adjusted difficulty level and pacing, individual risk factors for relapse related to skill building and practice need, different outcomes and paths based on user actions) with the goal of increasing user engagement and learning.27–29

The next step in research on this program and approach will be to examine its efficacy and effectiveness. In this feasibility trial, incentives were provided to participants in exchange for their feedback on the program; as part of the effectiveness investigations it will be important to examine adherence to the program in the absence of study-based incentives. In addition, we would like to investigate the effects of the program on longer-term sobriety and look at the relation between dosage (i.e., amount of interaction with the program) and outcomes. It will also be important to compare the success of “Arise” with that of other available programs. Because of the heterogeneous nature of aftercare, it also will be important to compare the effectiveness of “Arise” as a stand-alone treatment versus one used in conjunction with a mental health provider. Client factors such as strengths, resources, motivation, and personal agency are consistently shown to be the greatest predictor of treatment effectiveness,30 and “Arise” should lead to increases in each of these factors. If “Arise” is used as a stand-alone product, it will be important to determine whether factors such as ongoing therapeutic alliance play a role in the effectiveness of the product.31

Conclusions

This study contributes to our understanding of how games and other interactive technologies can be used to modify health-related behavior in areas beyond substance abuse. Adolescents and treatment providers liked the interactive lessons and skill-building games, found them easy to use, and thought they would be helpful and effective. Participants expressed a strong interest in “Arise,” indicating that programs like this are achievable, practical, and appropriate, as well as being a desired means of intervention delivery.

Evidence-based online intervention programs could offer several benefits over existing intervention options. They have the potential to reach many in need of services who do not receive them because of cost and limited locations of care, lack of transportation, scheduling difficulties, or insurance concerns. Another advantage of interactive technologies for intervention delivery is that adolescents' interest as shown in this and other studies20 may lead to more active, willing participation in online compared with traditional intervention, and this greater engagement could translate to more interaction time and a larger “dose” of the program. By maximizing accessibility, affordability, and engagement through efficient and easy-to-use online deployment that requires no additional software, hardware, or technical expertise on the part of users, we can provide greater access to effective intervention. Appealing online intervention programs such as “Arise” greatly expand the opportunities beyond traditional intervention modalities and provide a promising direction for games for health.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, under contract number HHSN271201300005C.

Author Disclosure Statement

R.P.S. and C.M.B. are employees of 3C Institute, which conducted this study. The software may be released by this company as a commercial product in the future.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. NSDUH Series H-46. HHS Publication Number (SMA) 13-4795. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown SA, Vik PW, Creamer VA. Characteristics of relapse following adolescent substance abuse treatment. Addict Behav 1989; 14:291–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornelius JR, Maisto SA, Pollock NK, et al. Rapid relapse generally follows treatment for substance use disorders among adolescents. Addict Behav 2003; 28:381–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tripodi SJ, Bender K, Litschge C, Vaughn MG. Interventions for reducing adolescent alcohol abuse: A meta-analytic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010; 164:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burleson JA, Kaminer Y, Burke RH. Twelve-month follow-up of aftercare for adolescents with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat 2012; 42:78–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll KM. Relapse prevention as a psychological treatment: A review of controlled clinical trials. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 4:46–54 [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Westhuizen M. Relapse prevention: Aftercare services to chemically addicted adolescents. Best Pract Ment Health 2011; 7(2):26–41 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzales R, Ang A, Murphy DA, et al. Substance use recovery outcomes among a cohort of youth participating in a mobile-based texting aftercare pilot program. J Subst Abuse Treat 2014; 47:20–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monti PM, Kadden RM, Rohsenow DJ, et al. Treating Alcohol Dependence: A Coping Skills Training Guide, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadden RM. Cognitive-behavior therapy for substance dependence: Coping skills training. Illinois Department of Human Services Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse. 2002. www.bhrm.org/guidelines/CBT-Kadden.pdf (accessed October15, 2014)

- 11.Miller WR, Hester RK. Treating alcohol problems: Toward an informed eclecticism. In: Hester RK, Miller WR, eds. Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches: Effective Alternative. New York: Pergamon Press; 1989: 3–13 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connors GJ, DiClemente CC, Velasquez MM, Donovan DM. Substance Abuse Treatment and the Stages of Change: Selecting and Planning Interventions, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magill M, Ray LA. Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2009; 70:516–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems. In: Marlatt GA, Donovan DM, eds. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 2005: 1–44 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latimer WW, Newcomb M, Winters KC, Stinchfield RD. Adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome: The role of substance abuse problem severity, psychosocial, and treatment factors. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:684–696 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyer KE, Phillips R, Wallis M, et al. Balancing cognitive and motivational scaffolding in tutorial dialogue. Presented at the 9th International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems Montreal, Canada, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corbett A, Koedinger K, Hadley W. Cognitive tutors: From research to classrooms. In: Goodman PS, ed. Technology Enhanced Learning: Opportunities for Change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001: 235–263 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon AS. Authoring branching storylines for training applications. In: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of Learning Sciences ICLS-04 New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2004: 22–26 [Google Scholar]

- 19.VanLehn K, Lynch C, Schulze K, et al. The Andes physics tutoring system: Lessons learned. Int J Artif Intell Educ 2005; 15:147–204 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trudeau KJ, Ainscough J, Charity S. Technology in treatment: Are adolescents and counselors interesed in online relapse prevention? Child Youth Care Forum 2012; 41:57–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell ANC, Nunes EV, Miele GM, et al. Design and methodological considerations of an effectiveness trial of a computer-assisted intervention: An example from the NIDA clinical trials network. Contemp Clin Trials 2012; 33:386–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girard B, Turcotte V, Bouchard S, Girard B. Crushing virtual cigarettes reduces tobacco addiction and treatment discontinuation. Cyberpsychol Behav 2009; 12:477–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res 2011; 45:626–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller WR, Marlatt GA. Manual for the Comprehensive Drinker Profile. Odessa FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis JR. Psychometric evaluation of the post-study system usability questionnaire: The PSSUQ. In: Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 36th Annual Meeting Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; 1992: 1259–1263 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: System characteristics, use perceptions and behavioral impacts. Int J Man Machine Stud 1993; 38:475–487 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ke F. Computer games application within alternative classroom goal structures: Cognitive, metacognitive, and affective evaluation. Educ Technol Res Dev 2008; 56:539–556 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papastergiou M. Digital game-based learning in high school computer science education: Impact on educational effectiveness and student motivation. Comput Educ 2009; 52:1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuzun H, Yilmaz-Soylu M, Karakus T, et al. The effects of computer games on primary students' achievement and motivation in geography learning. Comput Educ 2009; 52:68–77 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bohart AC, Tallman K. Clients: The neglected common factor in psychotherapy. In: Duncan BL, Miller SD, Wampold BE, Hubble MA, eds. The Heart & Soul of Change: Delivering What Works in Therapy, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010: 83–111 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duncan BL, Miller SD, Wampold BE, Hubble MA, eds. The Heart & Soul of Change: Delivering What Works in Therapy, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010 [Google Scholar]