Introduction

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid cancer in childhood and the most common cancer in infancy, with nearly 90 percent of cases occurring in children younger than five years of age [1,2]. It is a malignancy of multipotent embryonic neural crest cells. Age, stage, and N-myc amplification are important prognostic factors and are used for risk stratification and treatment assignment. The differences in outcome for patients with neuroblastoma are striking: low- and intermediate-risk patients have an excellent prognosis and outcome whereas those with high-risk disease continue to have poor outlook despite intensive therapy [3]. This is especially true for patients older than 18 months at diagnosis with metastatic disease to bone, bone marrow, liver, and lymph nodes. A better understanding of the tumor stem cell may offer alternative strategies for more effective treatment.

Previous studies have shown that distinct cell types are present in human neuroblastoma cell lines and tumors [4,5]. In vitro, the three cell types differ markedly with regard to their morphology, biochemistry, and malignant potential. The most abundant are neuroblastic (N-type) cells which have small, rounded cell bodies with short neuritic processes and, in culture, attach weakly to the underlying substrate or grow as clumps of floating cells. These cells possess neuronal marker proteins and are mildly tumorigenic. By contrast, non-neuronal, substrate-adherent (S-type) cells grow as a contact-inhibited monolayer with a large cytoplasmic/nuclear ratio. They possess marker proteins identifying them as non-neuronal neural crest-derived cells, such as melanocytes, glial, or smooth muscle cells. Cells with this phenotype are non-tumorigenic [6]. A third cell type, termed I-like because of a morphology intermediate between N- and S-type cells, has been shown to be a stem-like cell [5]. These cells possess marker proteins of both N and S phenotypes. Of particular interest, I-type cells are 4- to 5-times more tumorigenic than N-type cells. In N-myc non-amplified tumors, increased frequency of these stem-like cells correlated with disease progression and poor survival [7]. Moreover, the I-type cells were shown by semi-quantitative RT-PCR to express high levels of two known stem cell markers, CD133 and KIT [5].

In the present study, we have confirmed and extended these findings by qRT-PCR and Western blotting to identify five genes in addition to CD133 and KIT whose mRNA and protein expression were significantly elevated in the I-type cancer stem cell compared to either N or S cells. The identification of these genes, elevated in the most malignant neuroblastoma cell type, could provide the basis for developing novel therapies focusing on stem cells or stem-like cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and differentiation

Six human neuroblastoma I-type [BE(2)-C, SK-N-MM, SK-N-HM, SK-N-LP, CB-JMN, and SH-IN], five N-type [BE(2)-M17, SH-SY5Y, KCN-69n, SK-N-BE(1)n, and LA1-55n], and four S-type [SH-EP1, LA1-5s, SMS-KCNs, and SK-N-BE(2)s] enriched populations or clonal cell lines were included in this study and have been described, in part, previously [5]. Cells were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (with non-essential amino acids) and Ham’s Nutrient Mixture F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT) without antibiotics. In differentiation studies, the I-type BE(2)-C cell line was grown for 7–21 days in the presence of 10 μM all-trans retinoic acid (RA) or 10 μM 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BUdR), concentrations determined in earlier studies to yield optimal differentiation into either N or S cells, respectively [5,8].

Semi-quantitative and real-time reverse transcription polymerase reaction (RT-PCR)

In studies of placental growth factor (PlGF) splice variants, semi-quantitative RT-PCR was used to assess which variant was more highly expressed in I-type cells. Products were separated on 1.6 % agarose gels and the amount of product measured by densitometry. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using a StepOne thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Relative mRNA level of a target gene was measured by the ΔΔCT method. In this method, expression levels of target mRNAs in each cell line were normalized to an endogenous control (glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPD]), and then expressed as a fold change to that of a reference calibrator cell line (SH-SY5Y). The thermocycle parameters were: 95°C for 30 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 seconds, and 60°C for 15 seconds. The primer sets used are available upon request.

Immunoblot analyses

Cells in exponential growth phase were lysed by the method of Ikegaki et al. [9] and proteins separated by standard techniques [10]. Blots were probed with antibodies to prominin 1, Notch1, c-kit, G-coupled protein receptor C5C, placental growth factor, secretogranin 2, and neurofilament 160 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Bound antibody was detected by chemiluminescence using secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The amount of protein was quantified by scanning densitometry of resulting Kodak XAR films and normalized to heat shock protein 72/73 (Hsp70) [Ab-1] (Oncogene Research Products, Boston, MA). Band specificity was confirmed using protein standards.

Stable Transfection

Plasmids containing NOTCH1 (Sigma–Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO) shRNA constructs were transfected into I-type BE(2)-C cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions; stable transfectants were selected with 100–500 μg/ml Geneticin (G418) (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Selected populations were isolated using cloning cylinders and used for further experiments.

Transformation assay

Anchorage-independent growth ability was measured by growth in soft agar (0.33% Difco Bacto agar) [5]. Mean colony-forming efficiency (CFE; the number of colonies divided by cell inoculum × 100) was determined in duplicate in two to four independent experiments.

Results

Microarray Analyses

Microarray analyses were performed on 13 human neuroblastoma enriched populations or clones to compare differential gene expression in the N, I, and S cells to identify genes up-regulated in I-type cells which might contribute to either their stem cell features and/or their high malignant potential. To confirm the validity of the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 (HG133 Plus 2) microarray with regard to cell phenotype, we examined expression levels of markers we had previously shown to reflect cell phenotype in the three cell variants [5]. Three N-type [neurofilament 68 (NFL), dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH), and chromogranin A (CHGA)] and three S-type [vimentin (VIM), Homing cell adhesion molecule/CD44 (HCAM), and α-actinin4 (ACTN4)] markers were analyzed in the 13 cell variants. High level expression of N-type markers was evident in both N or I cell types whereas high level expression of S-type markers was pronounced, for the most part, only in S and I cells (Table 1).

Table 1.

Relative mRNA expression levels for N and S cell markers from the microarray

| Genea | Relative Expression Level (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nb | I | S | |

| N-marker | |||

| NFL | 100 ± 28 | 48 ± 29 | 6 ± 1 |

| DBH | 100 ± 38 | 54 ± 23 | 8 ± 1 |

| CHGA | 100 ± 13 | 99 ± 268 | 3 ± 1 |

| S-marker | |||

| VIM | 28 ± 12 | 65 ± 16 | 100 ± 17 |

| HCAM | 3 ± 1 | 14 ± 8 | 100 ± 29 |

| ACTN4 | 27± 8 | 35 ± 4 | 100 ± 44 |

Gene abbreviation: NFL, neurofilament 68kD; DBH, dopamine-β-hydroxylase; CHGA, chromogranin A; VIM, vimentin; HCAM, homing cell adhesion molecule (CD44); ACTN4, α-actinin4.

Phenotype: N, neuroblastic; I, intermediate stem cell; S, substrate-adherent (nonneuronal).

From the microarray, 64 genes were initially identified to be elevated more than 5-fold in I-type cells. Only seven genes were confirmed by qRT-PCR whose expression was consistently higher in all I-type cancer stem cells. They were: CD133, KIT, NOTCH1, GPRC5C, PlGF2, LNGFR, and TRKB. The elevated expression of two of these genes (CD133 and KIT) was previously reported using semi-quantitative RT-PCR [5]. To expand and validate the differential expression of each of these seven genes in human neuroblastoma I-type cells and to examine their potential roles in cancer stem cell biology, we used qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses to measure steady state mRNA levels and protein amounts of the genes in N, I, and S cell clones. We also examined the effects of induced differentiation on their levels of expression. Finally, for NOTCH1, we studied, using shRNA methods, the effects of reducing gene expression on the differentiation and malignant potential of I-type cells.

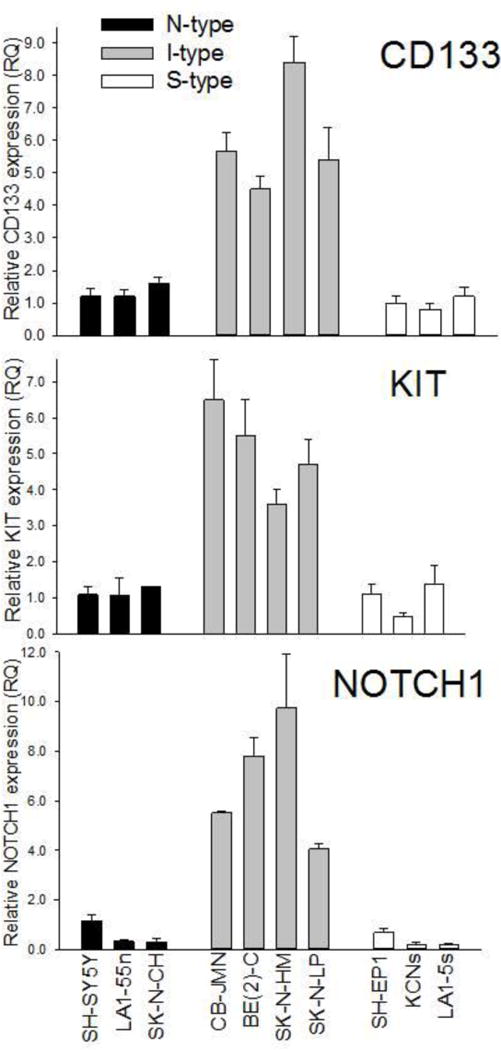

CD133

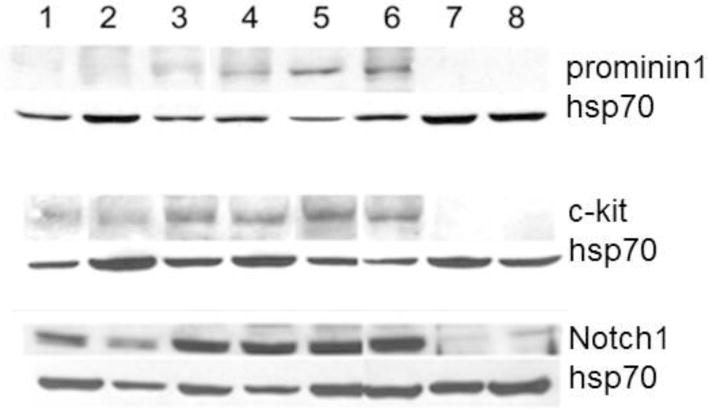

In 10 human neuroblastoma phenotypic variants, steady state RNA levels were measured for the stem cell marker gene CD133. This cell surface protein (prominin 1) is expressed in hematopoietic stem cells [11] and all human fetal neural stem cells [12,13]. I-type cells have abundant mRNA for CD133 compared to N and S cells seen using semi-quantitative RT-PCR [5]. We confirmed and extended these findings using qRT-PCR (Figure 1) to show that CD133 expression was nearly 5-fold higher in I cells compared to either N or S cell variants. Western blot analysis showed that prominin 1 protein amounts were also significantly (5-fold) higher in I-type cells (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Differential mRNA expression of CD133, KIT, and NOTCH1 in human neuroblastoma cell variants. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 6–9 separate determinations.

Figure 2.

Representative western blots of prominin1, c-kit, and Notch1 in 8 human neuroblastoma cell variants. Note that the amount of protein in I-type cells is consistently higher that in N and S variants. Lane, line: 1, (phenotype): 1, SH-SY5Y (N); 2, BE(2)-M17 (N); 3, SK-N-HM (I); 4, CB-JMN (I); 5, SK-N-LP (I); 6, BE(2)-C (I); 7, BE(2)s (S); and 8, SH-EP1 (S).

KIT

The c-kit antigen (v-kit Hardy-Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma viral oncogene homolog), encoded by the KIT gene, is present in both hematopoietic stem cells [11] and a subpopulation of neural crest stem cells [14]. Figure 1, summarizing data from one to four independent experiments, in 10 cell lines, showed differential KIT expression in N, S, and I cell variants with the I-type cells showing the highest KIT expression levels. Thus, KIT, a stem cell marker, was expressed at high levels in I-type neuroblastoma cells, compared with either N-type or S-type cells. Similar to its differential mRNA expression levels, c-kit protein was also elevated in I-type cells. As Figure 2 demonstrates, in Western blot analysis with proteins from N-, I-, and S-type cells, c-kit protein amounts in the I-type cancer stem cells were nearly 4-fold greater than in N-type cells and 10-fold greater than in S-type cells.

NOTCH1

NOTCH1 (translocation-associated Notch homolog 1) is one member of a family of transmembrane receptors that function in cell fate decisions. When ligand is bound, Notch1 is cleaved by γ-secretase-mediated proteolysis, releasing its intracellular domain which translocates to the nucleus to function as a transcriptional activator [15,16]. Figure 1 shows differential NOTCH1 mRNA expression in N, S, and I cell variants. I-type cells showed significantly higher levels of NOTCH1 expression compared to their N and S cell counterparts. By contrast, mRNA expression levels of three other members of the NOTCH family were highest in S cells and lower in N and I cells (data not shown). Western blot analyses confirmed that Notch1 protein amounts were noticeably higher in I-type cancer stem cells than the N-type or S-type cells (Figure 2).

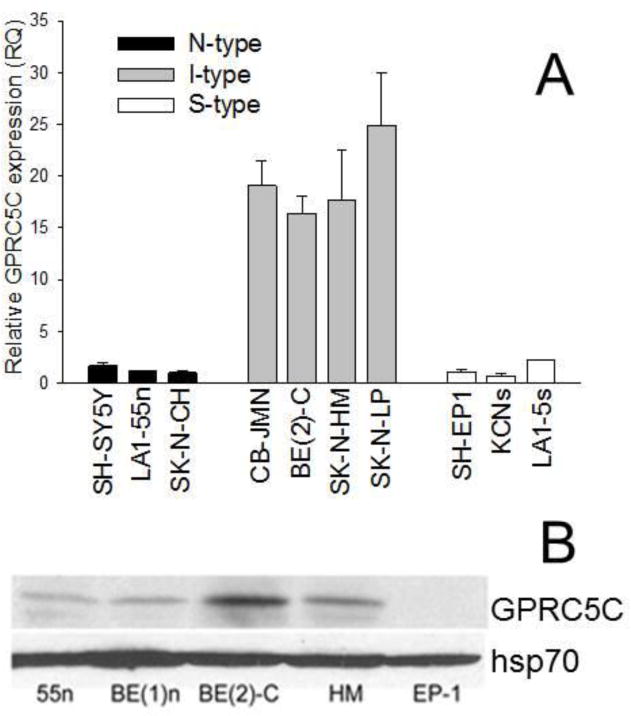

GPRC5C

The G-protein-coupled receptor, family C, group 5, member C is expressed on the cell surface in peripheral tissues and is increased following all-trans-retinoic acid treatment [17]. Its function is unknown. Figure 3A shows qRT-PCR expression in N-, I-, and S-type cells, where the mRNA levels of GPRC5C were significantly (15-fold) higher in I-type cells compared to either N or S cells. Figure 3B shows that GPRC5C protein was also significantly elevated in I cells compared to N and S variants.

Figure 3.

Differential mRNA expression and protein amounts of GPRC5C in human neuroblastoma cell variants. A. GPRC5C mRNA levels. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 4–6 separate determinations. B. Representative western blot of GPRC5C and hsp70. Note that that the protein levels are significantly higher in the two I type cell lines, BE(2)-C and HM, compared to either N-type lines, 55n and BE(1)n, or the EP-1 S cell line.

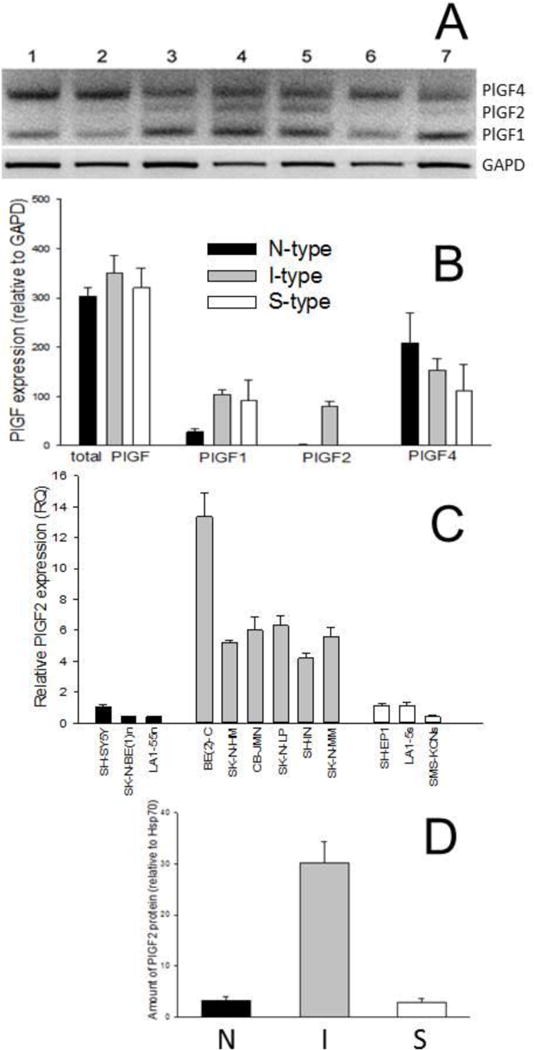

PlGF2

Placental growth factor (PlGF) is an angiogenic protein of the vascular endothelial growth factor family. Alternative splicing generates four different isoforms which have different receptor binding affinities and different tissue distribution [18]. PlGF1 and PlGF3 are secreted, diffusible proteins whereas both PlGF2 and PlGF4 isoforms are membrane-associated as they contain a heparin-binding domain. PlGFs have been implicated in the aggressive capacity of cancers by inducing angiogenesis, promoting cell motility and metastasis, and increasing cell survival [18–20]. Using primers to simultaneously detect three different PlGF isoforms (Figure 4A), semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis shows that neuroblastoma cells produced PlGF1, 2, and 4 by alternative splicing of the same transcript. Whereas the amount of total PlGF mRNA was not different among the three cell phenotypes, PlGF1 was more abundant in I- and S-type cells (Figure 4B). PlGF4 was the most abundant splice variant and its level of expression was not significantly different among the three cell types. By contrast, PlGF2 mRNA levels were very high in I-type cells and nearly absent in N and 5 cells (Figure 4A). Real-time RT-PCR was used to measure levels of PlGF2 in 12 neuroblastoma variants and showed that this growth factor was elevated 6-fold in the six I-type lines compared to both N- and S-type lines (Figure 4C). This differential gene expression was also seen at the protein level, as I-type cells showed ~10-fold elevated amounts of PlGF2 compared to either N or S cells (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Differential mRNA expression of three different placental growth factors (PlGF) in human neuroblastoma cell variants. A. Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel showing differential expression of the three different PlGF splice variants in N, I, and S cell variants. B. Quantification of amounts of the total and individual PlGF splice variants. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 5 separate determinations. C. qRT-PCR levels of PlGF2 in 12 human neuroblastoma cell variants. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 4–6 determinations. D. Amount of PlGF2 protein in human neuroblastoma cells relative to Hsp70. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of 2–3 determinations of 2–4 different cell variants.

Neurotrophic Receptors (NTRs)

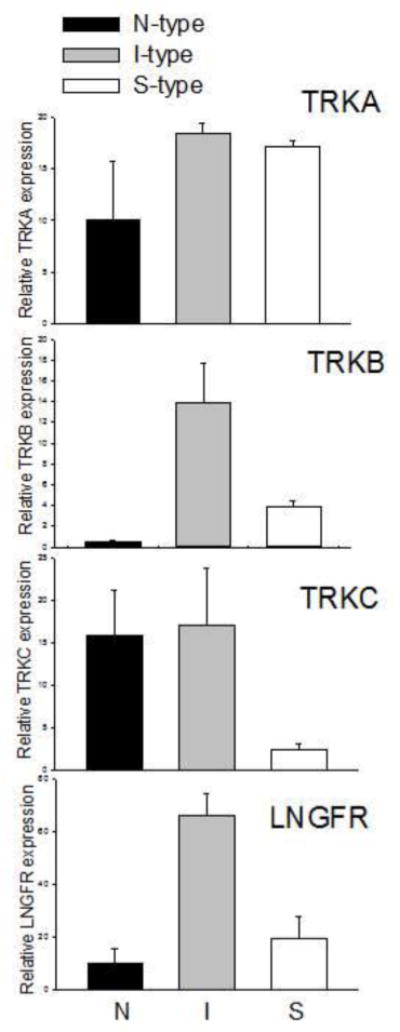

The neurotrophins are a family of closely related proteins that play roles in the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of neuro-epithelial precursors, including the neural crest [21–23]. The effects are mediated through activation of neurotrophin receptor tyrosine kinases (trkA, B, or C) and the p75 low affinity nerve growth factor receptor (LNGFR). Several studies have identified these specific receptors in neuroblastoma cell lines and tumors and have identified their roles in tumor stage, drug-resistance, and patient survival [24–27]. We examined the mRNA expression of the four NTRs in groups of the three neuroblastoma cell variants and show that (1) there were no significant differences among the cell phenotypes in TRKA expression and (2) TRKC mRNA levels were significantly higher in N- and I-type cells compared to S-type cell lines (Figure 5). More importantly, both TRKB and LNGFR mRNA levels were significantly higher (3.4- to 26.7-fold higher) in I-type cells compared to that in N or S cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Differential mRNA expression of the four neurotrophic receptors in human neuroblastoma cell variants, neuroblastic (N), non-neuronal (S), and I-type cell (I). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 4–6 determinations. Note that whereas there is no significant differences in TRKA expression and both N and I variants express higher levels of TRKC compared to S-type, both TRKB and LNGFR are significantly more highly expressed in I-type cells compared to either N or S cell variants Expression values are relative to GAPD.

Effect of induced differentiation on gene expression

To determine whether the expression of these stem cell-related genes is regulated by cell phenotype, we induced bidirectional differentiation in the I-type BE(2)-C cell line by treatment with either retinoic acid (RA), to generate a neuroblastic (N-type) phenotype, or bromodeoxyuridine (BUdR), to induce a non-neuronal, S-cell phenotype [5,8]. Biochemically, RA-induced neuroblastic differentiation of I-type stem cells is characterized by significant 2– to 10-fold increases in neural-specific markers - two neurotransmitter biosynthetic enzymes (tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine-β-hydroxylase), two cytoskeletal proteins (β-tubulin and the intermediate size neurofilament [NFM]), and the neuronal-related granin secretogranin (Sg2) [8]. Conversely, BudR-induced S-type nonneuronal differentiation is characterized by significant decreases in all of the above proteins [8].

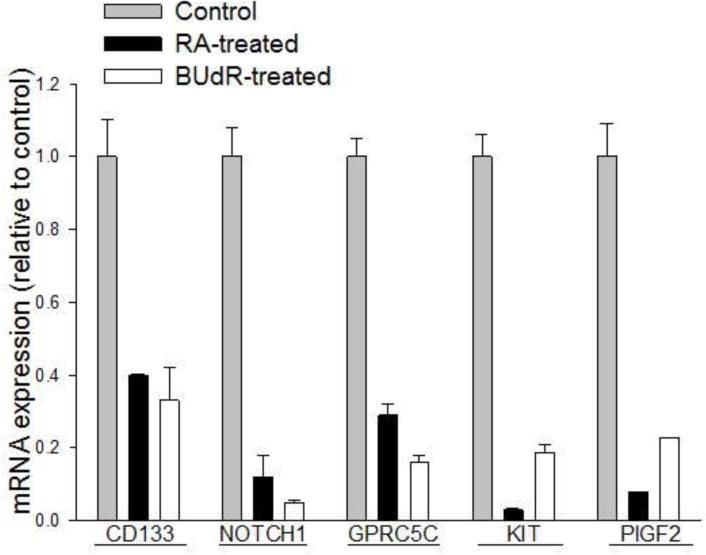

Differentiation along either pathway resulted in a significant decrease, ranging from a 2.5- to a 20-fold, in the expression of five of the seven genes (Figure 6). Their high level expression appeared to be specifically regulated by cell phenotype and, thus, was characteristic of the cancer stem cell phenotype in human neuroblastoma.

Figure 6.

Changes in mRNA expression of five neuroblastoma stem cell markers in response to differentiation. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 4–5 separate determinations and is expressed relative to control.

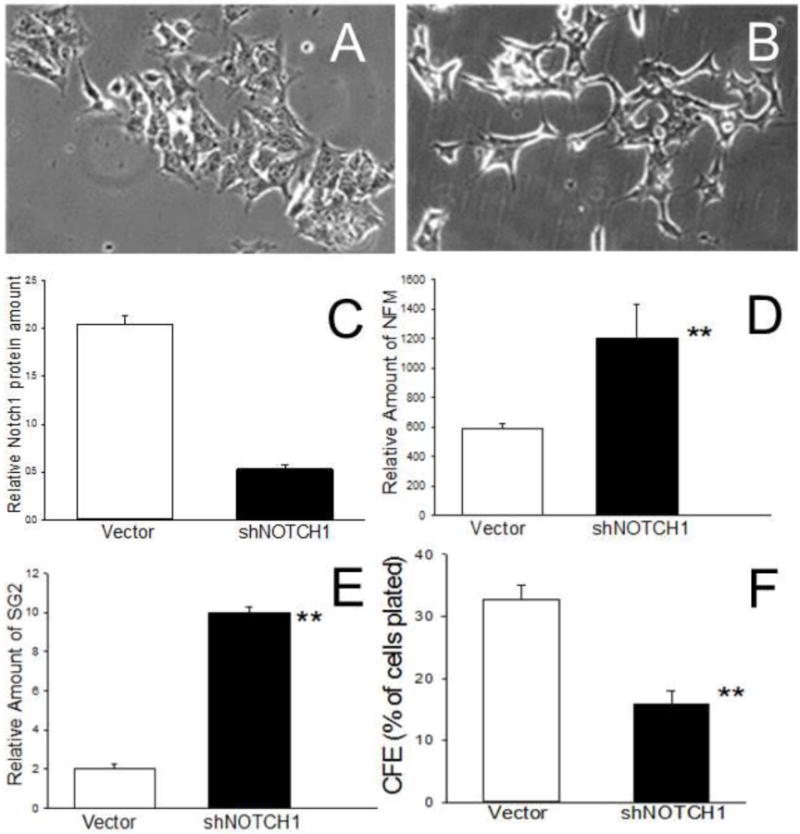

Selective inhibition of NOTCH1

Recent studies have shown that Notch signaling plays an essential role in maintaining a neural stem cell phenotype in the developing nervous system [28]. To determine the role of NOTCH1 in human neuroblastoma cancer stem cell biology, we transfected highly malignant I-type BE(2)-C cells with an shNOTCH1 construct (4 μg) and selected clones on G418. Compared to vector-transfected controls (Figure 7A), antisense NOTCH1-transfected cells appeared more neuroblastic (Figure 7B) with a >4-fold reduction in Notch1 protein (Figure 7C). The shNOTCH1 transfectants also showed increased expression of two neuronal-specific proteins - 160 kD neurofilament protein [NFM] (2-fold) (Figure 7D) and secretogranin 2 [SG2] (5-fold) (Figure 7E). In addition, there was a significant 2-fold reduction in their tumorigenic potential as reflected in their colony-forming efficiency in soft agar (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

Effects of antisense NOTCH1 on differentiation and tumorigenic phenotype in human neuroblastoma BE(2)-C I-type cells. Transfection of BE(2)-C cells with 4μg/ml shNOTCH1 results in a neuroblastic morphology (B) compared to vector-transfected control (A) cells. shNOTCH1 transfectants also showed a >4-fold decrease in Notch1 protein (C) and significant increases in neuronal specific markers neurofilament 160 [NFM] (D) and secretogranin 2 [SG2], relative to Hsp70 (E) with decreased colony forming efficiency in soft agar (F). ** p> 0.01.

Discussion

We have previously shown that cellular phenotype is an important determinant of the malignant potential in human neuroblastoma cells and tumors [5]. In particular, in those experiments, we identified a stem cell phenotype in human neuroblastoma which was at least 5-fold more tumorigenic than either of the other two predominant cell types. Moreover, we showed that the frequency of this stem cell type in N-myc non-amplified neuroblastoma tumors correlated with a poor clinical outcome [7]. In the present study, we sought to determine which genes were overexpressed in this cell type which might promote and/or maintain the stemness and/or the malignancy of human neuroblastoma cancer stem cells. For this study, we used a microarray platform which compared the steady-state expression levels of mRNAs from 13 human neuroblastoma cell lines representing the three predominant cellular phenotypes. We identified seven genes whose expression was significantly and consistently elevated in I-type cells – CD133, KIT, GPRC5C, NOTCH1, PlGF2, TRKB, and LNGFR.

Several previous studies, including our own [5] have identified CD133 as both a stem cell marker as well as a marker for a poor clinical outcome in cancers, including neuroblastoma and other nervous system cancers [29]. Two different mechanisms have been proposed for mediating these effects. Sartelet and colleagues have shown that overexpression of CD133 is associated with poor clinical outcome in neuroblastoma and is associated with increased chemoresistance [30]. More recently, studies have revealed that CD133 enhances radioresistance in glioblastoma stem-like cells [31]. By contrast, Takenobu et al. have reported that CD133 suppresses neuroblastoma cell differentiation via suppression of RET signaling [32]. In many tissues, including fetal neural tissue, cells with elevated CD133 are capable of self-renewal [13].

Likewise, c-kit has been identified as a marker of normal stem cells, such as hematopoietic and neural crest cells, as well as in several cancers, including glioma and neuroblastoma [33,34]. In neural crest stem cells, from which neuroblastomas arise, c-kit has been shown to support stem cell survival and has been suggested to play a role in the growth regulation of neuroblastoma [35]. Other studies have delineated a role for c-kit in glioma cell migration/metastasis and radioresistance [34,36].

G-coupled protein receptor C5C (GPRC5C) is a member of the G proteincoupled receptor superfamily, characterized by a signature 7-transmembrane domain motif. The specific function of this protein is not known. However, examination of the GEO database in mice revealed that this specific G-coupled protein receptor is more highly expressed in dorsal root ganglia (derived from neural crest) compared to spinal cord and is significantly higher in differentiated embryonic stem cells when compared to undifferentiated stem cells [37]. Thus, the elevated expression and higher protein amounts of GPRC5C in neuroblastoma stem cells may signify its peripheral neuroectodermal origin and its differentiated embryonic stem cell state.

A primary function of Notch signaling in the nervous system is to restrict further differentiation of the stem cell. Several studies in neuroblastoma cells have shown that Notch1 expression is required for the maintenance of neural stem cells by the suppression of proneural genes [28]. In neuroblastoma cells, Notch1 inhibition has been shown to lead to neuronal/neuroendocrine differentiation [38]. Thus, elevated levels of Notch1 suppress differentiation and keep the cells in an undifferentiated “stem cell” state. In the present study, we show that suppression of NOTCH1 leads to neuronal differentiation and reduced malignant potential. One proposed candidate for negative regulation of the Notch1 gene is the Krüppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) tumor suppressor gene. Klf4 binds to the Notch1 promoter and its overexpression in normal cells is sufficient to down-modulate NOTCH1 gene transcription [39]. Klf4 suppresses neuroblastoma cell growth and determines non-tumorigenic lineage differentiation and lower Klf4 expression is associated with unfavorable neuroblastoma outcome in patients [40].

Placental growth factor (PlGF) is an angiogenic protein often highly upregulated in solid tumors contributing to their growth and survival [41]. PlGF can promote angiogenesis either by directly stimulating endothelial cell growth or by recruiting proangiogenic cell types. Of the two main human PlGF isoforms, PlGF1 and PlGF2, only PlGF2 has the exclusive ability to bind heparin and neuropilin receptors. Elevated circulating PlGF in neuroendocrine tumors correlates with advanced tumor grading and reduced patient survival [42]. Studies also suggest that PlGF2 may promote dorsal root ganglion survival and prevent neurite collapse [43], thus providing an additional role for this growth factor in cell survival. Of the four PlGFs, PlGF2 appears to bind to the most diverse number of receptors, including VEGFR-1, HSPG, NRP-1, and NRP-2 [44].

Previous studies have shown that neurotrophins, through their cognate receptors, regulate the proliferation, survival, and differentiation of neural crest cells as well as CNS neuro-epithelial precursors [21]. Numerous studies have examined their presence and role in neuroblastoma [24–27,45–48], including studies which show the roles of NTRs in survival, invasiveness, and chemoresistance. In the present study, we show that both TRKB and LNGFR were significantly higher in neuroblastoma stem cells when compared to the two other predominant cell types. This suggests that the increased survival, proliferation, invasiveness, and resistance seen in neuroblastoma tumors were mediated by the stem cell subpopulation.

The unique pattern of gene expression in neuroblastoma I-type cancer stem cells could provide these cells and the tumors which they comprise a specific set of proteins to enable them to survive and proliferate under various unfavorable environments, even in hypoxic conditions within large bulky solid tumors or at metastatic sites such as the bone marrow. Moreover, some of these genes allow the stem cells to promote angiogenesis and provide chemoresistance for the growing tumor. This combination of properties positions the neuroblastoma stem cell to survive, metastasize, and proliferate. Knowledge of the genes which mediate these features may provide new avenues for the more effective treatment of this often fatal childhood cancer.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Human neuroblastoma stem cells have a unique gene expression profile.

NOTCH1 overexpression blocks neural/glial differentiation, maintaining the highly malignant character of these stem cells.

PlGF2 overexpression may induce angiogenesis, enabling these solid tumors to survive and proliferate.

Elevated TRKB and LNGFR mRNA levels may prevent apoptosis and promote chemoresistance.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA 77593). This paper is dedicated to Dr. June L. Biedler and Barbara A. Spengler, who initiated the research on phenotypic plasticity in human neuroblastoma cells.

Abbreviations

- ACTN4

α-actinin4

- BUdR

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- CFE

colony-forming efficiency

- CHGA

chromogranin A

- DBH

dopamine-β-hydroxylase

- GAPD

glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase

- G418

Geneticin

- GPRC5C

G-protein-coupled receptor, family C, group 5, member C

- HCAM

Homing cell adhesion molecule/CD44

- Hsp70

heat shock protein 72/73

- I-type

intermediate stem cell

- Klf4

Krüppel-like factor 4

- LNGFR

p75 low affinity nerve growth factor receptor

- N-type

neuroblastic

- NFL

neurofilament 68

- NFM

neurofilament 160

- NTRs

Neurotrophic receptors

- PlGF

placental growth factor

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- RA

all-trans retinoic acid

- RQ

relative quantification

- S-type

substrate-adherent non-neuronal

- SG2

secretogranin 2

- Trk

tyrosine kinase receptor

- VIM

vimentin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: none

Contribution: RAR, JDW, and N-KVC designed experiments and wrote the manuscript; RAR, JDW, DH, and H-FG performed research.

References

- 1.Gurney JG, Severson RK, Davis S, et al. Incidence of cancer in children in the United States. Cancer. 1995;75:2186–2195. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950415)75:8<2186::aid-cncr2820750825>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung NK, Dyer MA. Neuroblastoma: Developmental Biology, Cancer Genomics, and Immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2013;13:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nrc3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthay KK, Reynolds CP, Seeger RC, et al. Long-term results for children with high-risk neuroblastoma treated on a randomized trial of myeloablative therapy followed by 13-cis-retinoic acid: a Children’s Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1007–1013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8925. Errata, J Clin Oncol32: 1862–1863, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimada H, Chatten J, Newton WA, Jr, et al. Histopathologic prognostic factors in neuroblastic tumors: Definition of subtypes of ganglioneuroblastoma and an age-linked classification of neuroblastomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;73:405–416. doi: 10.1093/jnci/73.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walton JD, Kattan DR, Thomas SK, et al. Characteristics of Stem Cells from Human Neuroblastoma Cell Lines and in Tumors. Neoplasia. 2004;6:838–845. doi: 10.1593/neo.04310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spengler BA, Lazarova DL, Ross RA, et al. Cell lineage and differentiation state are primary determinants of MYCN gene expression and malignant potential in human neuroblastoma cells. Oncol Res. 1997;9:467–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross RA, Spengler BA. Human neuroblastoma stem cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross RA, Spengler BA, Domenech C, et al. Human neuroblastoma I-type cells are malignant neural crest stem cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:449–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikegaki N, Bukovsky J, Kennett RH. Identification and characterization of the NMYC gene product in human neuroblastoma cells by monoclonal antibodies with defined specificities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:5929–5933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazarova DL, Spengler BA, Biedler JL, et al. HuD, a neuronal-specific RNA-binding protein, is a putative regulator of N-myc pre-mRNA processing/stability in malignant human neuroblasts. Oncogene. 1999;18:2703–2710. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wognum AW, Eaves AC, Thomas TE. Identification and isolation of hematopoietic stem cells. Arch Med Res. 2003;34:461–475. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo R, Gao J, Wehrle-Haller B, et al. Molecular identification of distinct neurogenic and melanogenic neural crest sublineages. Development. 2003;130:321–330. doi: 10.1242/dev.00213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchida N, Buck DW, He D, et al. Direct isolation of human central nervous system stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14720–14725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, et al. Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15178–15183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036535100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balint K, Xiao M, Pinnix CC, et al. Activation of Notch1 signaling is required for beta-catenin-mediated human primary melanoma progression. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3166–3176. doi: 10.1172/JCI25001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckfeldt CE, Mendenhall EM, Flynn CM, et al. Functional analysis of human hematopoietic stem cell gene expression using zebrafish. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins MJ, Michalovich D, Hill J, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of two novel retinoic acid-inducible orphan G-protein-coupled receptors (GPRC5B and GPRC5C) Genomics. 2000;67:8–18. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribatti D. The crucial role of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor in angiogenesis: a historical review. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Honmou O, Harada K, et al. Neuroprotection by PlGF gene-modified human mesenchymal stem cells after cerebral ischaemia. Brain. 2006;129:2734–2745. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Ye L, Zhang L, et al. Placenta growth factor, PLGF, influences the motility of lung cancer cells, the role of Rho associated kinase, Rock1. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:313–320. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:677–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Duan X, Zhang H, et al. Isolation of neural crest-derived stem cells from rat embryonic mandibular processes. Biol Cell. 2006;98:567–675. doi: 10.1042/BC20060012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skaper SD. The neurotrophin family of neurotrophic factors: an overview. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;846:1–12. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-536-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakagawara A, Azar CG, Scavarda NJ, et al. Expression and function of TRK-B and BDNF in human neuroblastoma. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:759–767. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brodeur GM, Nakagawara A, Yamashiro DJ, et al. Expression of TrkA, TrkB and TrkC in human neuroblastomas. J Neuro-Oncol. 1997;31:49–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1005729329526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaboin J, Kim CJ, Kaplan DR, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of TrkB protects neuroblastoma cells from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis via phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase pathway. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6756–6763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura K, Martin KC, Jackson JK, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of TrkB induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression via hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4249–4255. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imayoshi I, Sakamoto M, Yamaguchi M, et al. Essential roles of Notch signaling in maintenance of neural stem cells in developing and adult brains. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3489–3498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4987-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tong QS, Zheng LD, Tang ST, et al. Expression and clinical significance of stem cell marker CD133 in human neuroblastoma. World J Pediatr. 2008;4:58–62. doi: 10.1007/s12519-008-0012-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sartelet H, Imbriglio T, Nyalendo C, et al. CD133 expression is associated with poor outcome in neuroblastoma via chemoresistance mediated by the AKT pathway. Histopathology. 2012;60:1144–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jamal M, Rath BH, Tsang PS, et al. The brain microenvironment preferentially enhances the radioresistance of CD133(+) glioblastoma stem-like cells. Neoplasia. 2012;14:150–158. doi: 10.1593/neo.111794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takenobu H, Shimozato O, Nakamura T, et al. CD133 suppresses neuroblastoma cell differentiation via signal pathway modification. Oncogene. 2011;30:97–105. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen PS, Chan JP, Lipkunskaya M, et al. Expression of stem cell factor and c-kit in human neuroblastoma. The Children’s Cancer Group Blood. 1994;84:3465–3472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serfozo P, Schlarman MS, Pierret C, et al. Selective migration of neuralized embryonic stem cells to stem cell factor and media conditioned by glioma cell lines. Cancer Cell Int. 2006;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sieber-Blum M, Zhang J-M. The neural crest and neural crest defects. Biomedical Reviews. 2002;13:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Losada J, Sanchez-Martin M, Perez-Caro M, et al. The radioresistance biological function of the SCF/kit signaling pathway is mediated by the zinc-finger transcription factor Slug. Oncogene. 2003;22:4205–4211. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pahlman S, Stockhausen MT, Fredlund E, et al. Notch signaling in neuroblastoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambertini C, Pantano S, Dotto GP. Differential control of Notch1 gene transcription by Klf4 and Sp3 transcription factors in normal versus cancer-derived keratinocytes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shum CK, Lau ST, Tsoi LL, et al. Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) suppresses neuroblastoma cell growth and determines non-tumorigenic lineage differentiation. Oncogene. 2013;32:4086–4099. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim KJ, Cho CS, Kim WU. Role of placenta growth factor in cancer and inflammation. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:10–19. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.1.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hilfenhaus G, Gohrig A, Pape UF, et al. Placental growth factor supports neuroendocrine tumor growth and predicts disease prognosis in patients. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:305–319. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng L, Jia H, Lohr M, et al. Anti-chemorepulsive effects of vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor-2 in dorsal root ganglion neurons are mediated via neuropilin-1 and cyclooxygenase-derived prostanoid production. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30654–30661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Falco S. The discovery of placenta growth factor and its biological activity. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:1–9. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.1.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dominici C, Nicotra MR, Alema S, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of p140trkA and p75LNGFR neurotrophin receptors in neuroblastoma. J Neuro Oncol. 1997;31:57–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1005781313596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aoyama M, Asai K, Shishikura T, et al. Human neuroblastomas with unfavorable biologies express high levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA and a variety of its variants. Cancer Lett. 2001;164:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hecht M, Schulte JH, Eggert A, et al. The neurotrophin receptor TrkB cooperates with c-Met in enhancing neuroblastoma invasiveness. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:2105–2115. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ho R, Eggert A, Hishiki T, et al. Resistance to chemotherapy mediated by TrkB in neuroblastomas. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6462–6466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]