Abstract

Purpose:

To describe the design, implementation, and evaluation of a tele-education system developed to improve diagnostic competency in retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) by ophthalmology residents.

Methods:

A secure Web-based tele-education system was developed utilizing a repository of over 2,500 unique image sets of ROP. For each image set used in the system, a reference standard ROP diagnosis was established. Performance by ophthalmology residents (postgraduate years 2 to 4) from the United States and Canada in taking the ROP tele-education program was prospectively evaluated. Residents were presented with image-based clinical cases of ROP during a pretest, posttest, and training chapters. Accuracy and reliability of ROP diagnosis (eg, plus disease, zone, stage, category) were determined using sensitivity, specificity, and the kappa statistic calculations of the results from the pretest and posttest.

Results:

Fifty-five ophthalmology residents were provided access to the ROP tele-education program. Thirty-one ophthalmology residents completed the program. When all training levels were analyzed together, a statistically significant increase was observed in sensitivity for the diagnosis of plus disease, zone, stage, category, and aggressive posterior ROP (P<.05). Statistically significant changes in specificity for identification of stage 2 or worse (P=.027) and pre-plus (P=.028) were observed.

Conclusions:

A tele-education system for ROP education is effective in improving diagnostic accuracy of ROP by ophthalmology residents. This system may have utility in the setting of both healthcare and medical education reform by creating a validated method to certify telemedicine providers and educate the next generation of ophthalmologists.

INTRODUCTION

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a vasoproliferative disease of the developing retina that occurs in premature infants. ROP was initially described in 1942 as “retrolental fibroplasia” and was believed to be due to unmonitored oxygen exposure in premature babies in developed countries. Since that time, seminal studies such as the Cryotherapy for ROP (CRYO-ROP) and the Early Treatment for ROP (ETROP) studies1,2 have improved our understanding of the disease and have laid the foundation for the advances in the diagnosis and treatment of ROP that we see today. Multidisciplinary approaches to ROP management, including advances in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) care, improved oxygen therapy, and a better understanding of the natural course of ROP, have led to better structural and functional outcomes for the disease. However, ROP continues to be a leading cause of childhood blindness in the United States,3 and we still face major clinical challenges in ROP because of such issues as the rapidly increasing number of premature births worldwide, a decreasing supply of qualified ophthalmologists who are able to manage ROP, limited exposure to ROP education by trainees, the precarious medicolegal environment for those who care for patients with ROP, and inequality of access to high-quality healthcare.

CHALLENGES IN RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY DIAGNOSIS

From a clinical perspective, we still do not have universally accepted methods of ensuring the diagnostic competency of ophthalmologists who manage ROP. Currently, ROP classification is standardized according to the criteria outlined by the International Classification of ROP (ICROP), which defines the relevant features of ROP (eg, zone, stage, and plus disease). As a result, most ophthalmologists who have trained in the past several decades depend on the definitions set forth by both the CRYO-ROP study and ICROP.2,4 However, despite the international classification of ROP, making the diagnosis of ROP remains subjective and qualitative, and numerous studies have shown significant variability in ROP diagnosis by experts.5–9 Specifically, diagnostic discrepancies between ROP experts have been demonstrated for the diagnosis of both zone I and plus disease.6,10 These inconsistencies have important clinical implications given that the accurate diagnosis of zone and plus disease is critical for our determination of treatment-requiring ROP. In addition, the CRYO-ROP study demonstrated disagreements in the diagnosis of threshold disease in 12% of eyes as determined by two unmasked certified examiners.2

Using methods from cognitive informatics to investigate the qualitative features of plus disease as perceived by ROP experts, our group has shown that very often ROP experts differ in their reasoning process and focus on different features of ROP that don’t necessarily fall within the traditional definitions of plus disease.11 This is representative of the challenges we face in clinical practice, where the diagnosis of ROP is not as straightforward as simply identifying the features defined by ICROP. There are subtle differences in perception and interpretation of relevant disease findings among ROP experts that may affect diagnosis.

For the inexperienced examiner, accurate diagnosis of ROP can prove to be even more challenging, and we have shown that ophthalmologists-in-training are less accurate in the diagnosis of clinically relevant disease (type 2 ROP and treatment-requiring ROP) compared to experienced ophthalmologists who manage ROP.12,13 The inability of ophthalmologists-in-training to diagnose ROP effectively is due to a number of issues, including limited experience and the lack of training programs that provide a formal ROP educational curriculum.

We aim to address these issues in diagnostic accuracy through improving education for ROP using tele-education methods. We believe that a tele-education system has the potential to address the challenges in ROP care as described in this study.

CHALLENGES IN EDUCATION FOR RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY AND THE WORKFORCE FOR RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY IN THE UNITED STATES

The clinical challenges in ROP care and management in the United States are multifactorial. One major issue is a workforce shortage of healthcare professionals who are adequately trained to manage ROP. Only about one-third of ophthalmologists provide care to children younger than 1 year, and substantially fewer ophthalmologists provide ROP care.14 A 2006 survey from the American Academy of Ophthalmology showed that only half of retina specialists and pediatric ophthalmologists were willing to manage ROP, and nearly 20% of these ophthalmologists planned to stop providing ROP care in the future.15 Among these respondents, the most common barriers were medical liability (67%) and poor reimbursement (37%).15 General ophthalmologists who are not fellowship-trained in retina or pediatric ophthalmology are also performing examinations for ROP. A study by Kemper and colleagues14 found that 11% of all ophthalmologists examine for ROP and 6% treat ROP. Many of these physicians had only completed residency training, and 9% of the ophthalmologists in that study felt that their ROP training was inadequate.12

This potential lack of adequate training in ROP care raises concerns. Our group has shown that general ophthalmologists in the first 2 years following residency training are less adept than experienced pediatric ophthalmologists and pediatric retina specialists at identifying clinically significant ROP when examining digital images.12,13 Therefore, we conducted surveys of ophthalmology residency training programs to determine how these programs in the United States are educating for ROP.

On examination of the current state of ROP training at the residency level in the United States, we noted that residents do not have the necessary clinical experience to become proficient in ROP diagnosis. We found that most residents receive limited or no exposure to ROP examination and treatment during residency, and most ophthalmology residents perform less than 20 ROP examinations during their residency training. Furthermore, ROP exams that were performed by ophthalmology residents sometimes did not have direct attending supervision.16 This lack of experience and instruction in ROP during residency is a likely explanation for why most of the pediatric ophthalmology and retina fellows who participated in a survey did not feel competent in evaluating ROP prior to fellowship.

At the fellowship level, there are also a number of concerns regarding education for ROP. For pediatric ophthalmology fellows, up to 15% of pediatric ophthalmology training programs exposed their fellows to minimal or no ROP.17 Pediatric ophthalmology fellows also perform significantly fewer laser photocoagulation procedures than retina fellows. In retina fellowship programs, fellows are infrequently provided with direct instruction and supervision during ROP examinations. We also found that many children at risk for ROP are receiving examinations by retina fellows only, without involvement and/or direct supervision by an attending ophthalmologist.16,18 Pediatric ophthalmology and retina fellows are also less accurate at diagnosing clinically significant disease (type 2 ROP and treatment-requiring ROP) as compared to experienced retina specialists.12,13 Therefore, in certain fellowship programs, children may be having examinations by ophthalmologists who are sometimes making an incorrect diagnosis and not recognizing ROP requiring treatment.

Currently there is no standardized method of formal evaluation of pediatric ophthalmology and retina fellows’ competency in ROP diagnosis that has been adopted throughout all fellowship programs. There is also a deficiency in validated educational tools and curriculum to ensure quality of training during residency and fellowship. The logistical issues around ROP training likely contribute to these deficiencies, and the inconsistent ROP training at the ophthalmology resident and fellow trainee level partly arises from the difficulties in having neonates receive multiple examinations.19 Infants may undergo a significant amount of stress during the indirect ophthalmoscopic examination, and examination by an ophthalmologist-in-training may cause increased morbidity for the neonate. Therefore, improved methods to educate ophthalmologists-in-training are necessary not only to improve exposure to ROP for trainees, but also to improve ROP care.

INTERNATIONAL CHALLENGES IN RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY

Globally, ROP remains a leading cause of childhood blindness and a major clinical challenge. A recent resurgence in the incidence of ROP, termed the “third epidemic,” has uniquely occurred in middle-income countries.20 Epidemiological evidence has suggested that the rate of preterm births tends to be higher in middle-income countries than in high-income countries. Middle-income countries face the unique conundrum of having sufficiently advanced medical facilities to decrease the infant mortality rate; however, they lack the needed resources to manage ROP appropriately.21 Middle-income countries suffer from (1) a lack of medical equipment for supplemental oxygen monitoring, (2) a shortage of ophthalmologists and healthcare providers with appropriate skills to screen for ROP, and (3) inadequate screening programs for ROP. If there are screening programs in place, screening protocols are often inconsistently implemented and some protocols are inappropriately designed to ensure that every child at risk for severe ROP is evaluated.21

In addition to the issues with inadequate screening programs, many middle-income countries lack the workforce to manage ROP appropriately. Just as in the United States, there are too few ophthalmologists and other healthcare providers who are experienced in ROP management. For example, it has been reported that in Lima, Peru, a single ophthalmologist was the sole provider of ROP care for a city of 8 million people.22 Also, many medical facilities lack adequate nursing and neonatology staff to allow for continuous oxygen monitoring and regulation.

For the most part, high-income and developed countries have been buffered from this recent resurgence in ROP cases because of high-quality neonatal services and evidence-based screening protocols. On the other hand, low-income countries have also been spared from the ROP resurgence because of poor survival of preterm infants from a lack of neonatal resources.20 However, as low-income countries begin to see improved economic development and improvements in healthcare, ROP will become a reality that will require a skilled workforce to address the problem.

TELE-EDUCATION AS AN APPROACH TO ADDRESSING THE CHALLENGES FOR RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY CARE

Advancements in Internet capacity and telecommunications have resulted in an exponential growth of telemedicine programs in fields of medicine that are optimized for image-based approaches. For example, dermatology, pathology, ophthalmology, and radiology are all well suited for telemedicine.23–25 Extensive studies over the past decades have demonstrated the utility of telemedicine in ROP for screening and to improve access to care.26–33

In addition to its utility in clinical care, digital imaging and Web-based platforms can be used to educate physicians who are inexperienced with ROP. Improved access to education for ROP through tele-education has the potential to address the need for increasing the workforce for ROP by improving ROP education in the United States and internationally. Tele-education has been used for a number of disciplines, such as emergency care, radiology, dermatology, neonatal resuscitation, and general continuing medical education. Previous reports have determined that a bandwidth of 28 kbit/s is sufficient for most distance learning activities.34–37 And with improved Internet capacity and the development of smart phones, tablets, and personal computers, the global online community has become more accessible. Regarding access to the Internet in developing countries, both the number of users and Internet capacity have grown significantly over the past 10 years.38,39 Therefore, as the ability to support the Internet grows, it becomes more feasible to perform telemedicine and tele-education.

THE GLOBAL EDUCATION NETWORK FOR ROP AND THE IMAGING AND INFORMATICS FOR ROP CONSORTIUM

Tele-education for ROP may potentially improve early diagnosis and treatment of ROP, increase the workforce that is able to manage children with this disease, and subsequently reduce the incidence of blindness due to ROP. We have organized a group of international collaborators with expertise in ophthalmology, neonatology, nursing, medical education, and informatics. This collaborative, the Global Education Network for Retinopathy of Prematurity (GEN-ROP), is interested in developing innovative ways to educate and increase the workforce for ROP. Together with the Imaging and Informatics for ROP (i-ROP) consortium, whose main purpose is to develop quantitative models relating the clinical, imaging, and genetic features of ROP and to examine genotype-phenotype correlations, we developed, and then administered, a tele-education system to improve diagnostic accuracy for ROP.

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

We aim to describe the design, implementation, and evaluation of the Web-based tele-education system we have developed, and we hypothesize that this system can improve competency in ROP diagnosis for ophthalmologists-in-training.

METHODS

The Weill Cornell Medical College (WCMC) Human Studies Committee approved all aspects of the use and analysis of retinal images and educational material used in this study. Administration and analysis of the tele-education system was also reviewed by the WCMC Human Studies Committee, and it was granted an exemption because it was considered research in an established or commonly accepted educational setting involving normal educational practices such as research on the effectiveness of instructional techniques, curricula, and instructional strategies. This study was conducted in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki and all federal and state laws and was in accordance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidelines.

STUDY POPULATION

Ophthalmology residents were recruited by the coauthors (K.E.J., R.V.P.C.), who contacted five residency programs in the United States and one residency program in Canada by email. All ophthalmology residents, postgraduate year (PGY)-2 to PGY-5, in these programs were allowed to participate in the ROP tele-education program. Only PGY-2 to PGY-4 residents were included in the analysis to control for level of training experience. Fifty-five PGY-2 to PGY-4 ophthalmology residents from five residency programs were given access to the ROP tele-education system. Thirty-one of these ophthalmology residents completed the program. Ophthalmology residents who did not complete the ROP tele-education program were excluded from the analysis in this study.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY TELE-EDUCATION SYSTEM

A secure Web-based database system was developed by the coauthors (R.V.P.C, K.E.J., S.O., M.F.C.) for this study and included a centralized repository of approximately 2,500 clinical cases with over 12,000 retinal images collected from eight study sites (https://tctc.ohsu.edu). This system served as the infrastructure for the development of a Web-based tele-education system, which utilized a subset of the clinical cases in the repository for educational purposes. The ROP tele-education system is a custom-designed system that utilizes standard and state-of-the-art software developed in collaboration between experienced ophthalmologists in ROP care and computer programmers. The system was coded in C# on the Microsoft ASP.NET platform (Microsoft) and employs a SQL Server database, which are currently among the most widely used software development tools for Web-based systems. To facilitate software development and compatibility across different Web browsers, the system was developed using an open source JavaScript wrapper called jQuery (Mozilla). The jQuery library enables a software component known as “plugins,” made by third parties, of which a number were used extensively for transitioning through the training chapters and images in the tele-education system.

DESCRIPTION OF THE RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY TELE-EDUCATION PROGRAM AND STUDY IMPLEMENTATION

Trainees who participated in the ROP tele-education program were provided unique access to a website where they could access the system. The tele-education program consisted of clinical cases presented in four unique sections: (1) a pretest, (2) a ROP tutorial, (3) ROP training chapters, and (4) a posttest.

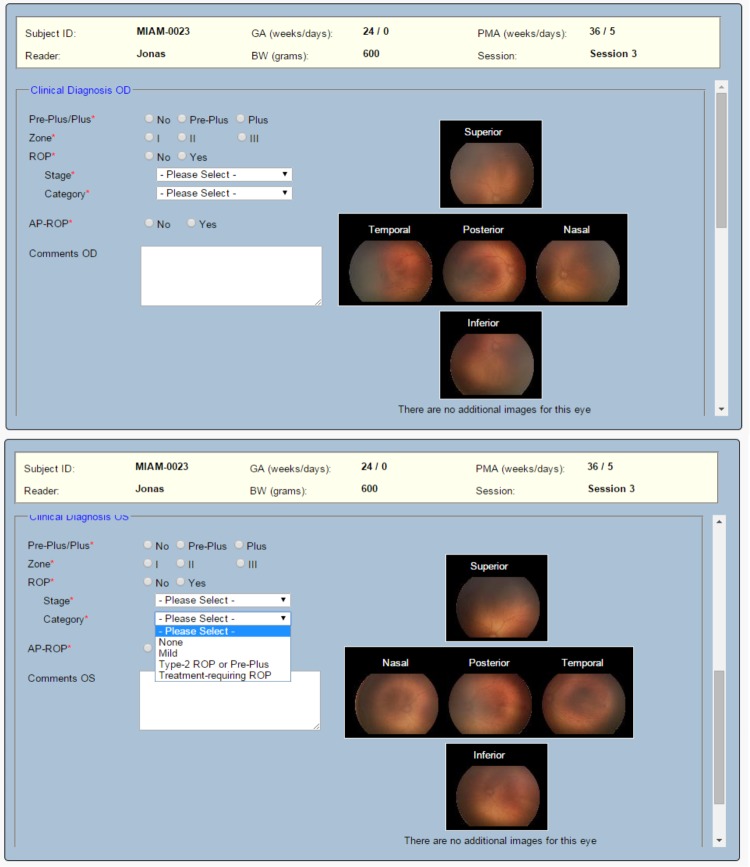

The trainee was asked to provide a clinical diagnosis in both eyes of one patient for each clinical case. The gestational age, birth weight, and postmenstrual age at the time of imaging were provided for each clinical case, and a set of retinal images (posterior, nasal, temporal) was included for each eye with additional images (eg, superior and inferior) being included if deemed to be clinically significant. Retinal images for both eyes were provided simultaneously, and a diagnosis of plus disease (no, pre-plus, plus), zone (I, II, III), ROP (yes, no), stage (1 through 5), category (none, mild, type 2 ROP or pre-plus, treatment-requiring ROP), and aggressive posterior ROP (APROP) (yes, no) was required for each individual eye (Figure 1). Type 2 ROP was defined as zone I, stage 1 or 2 ROP without plus disease or as zone II, stage 3 ROP without plus disease, and for the purposes of the tele-education program, treatment-requiring ROP was type 1 ROP or worse as defined by the ETROP Study.1

FIGURE 1.

Design of a clinical case in the retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) tele-education system. Each clinical case consisted of two eyes from one patient. Demographic information was provided to the trainee. Trainees were asked to provide a clinical diagnosis of plus disease (no, pre-plus, plus), zone (I, II, III), ROP (yes, no), stage (1–5), category (none, mild, type 2 ROP or pre-plus, treatment-requiring ROP), and aggressive posterior ROP (yes, no) for each individual eye. Trainees had the option to view OD and OS images simultaneously. For each individual color fundus photograph, a larger-resolution (1024×768) photograph was displayed if the trainee selected that photograph.

The trainees were placed on a weekly schedule such that they completed 1 to 2 sections of the tele-education program per week for a total of 8 sections. Weekly reminders were sent out to trainees by the study coordinator (K.E.J) to remind them about sections that needed to be completed that week.

Characteristics of the Clinical Cases Selected for the Retinopathy of Prematurity Tele-education System

A total of 36 infants were used for the 65 clinical cases (20 pretest, 20 posttest, and 25 training chapter–based) in the program. Both eyes of each infant underwent funduscopic imaging, for a total of 72 eyes. To ensure that a spectrum of disease was represented, we reviewed all of the cases from our clinical repository to determine which cases were to be used in the pretest, posttest, and training chapters. The relevant clinical characteristics of the cases are summarized in Table 1. Of the 16 unique cases (32 eyes) presented in the pretest and posttest, 10 eyes (31%) had no ROP, 6 (19%) had mild ROP, 10 (31%) had type 2 ROP, and 6 (19%) had treatment-requiring ROP. For the four repeated cases (8 eyes), there were 2 eyes each with no ROP, mild ROP, type 2 ROP, and treatment-requiring ROP. Of the 25 training chapter–based cases (50 eyes), 10 eyes (20%) had no ROP, 13 (26%) had mild ROP, 15 (30%) had type 2 ROP, and 12 (24%) had treatment-requiring ROP.

TABLE 1.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE EYES USED FOR THE CLINICAL CASES IN THE ROP TELE-EDUCATION SYSTEM

| Diagnosis |

Eyes Included in

the Unique Cases of the Prestest and Posttest (N=32) |

Eyes Included in

the Repeated Cases of the Pretest and Posttest (N=8) |

Eyes Included in

the Training Chapter Cases (N=50) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone | |||

| I | 4 | 2 | 15 |

| II | 28 | 6 | 35 |

| III | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stage | |||

| 0 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 11 |

| 2 | 4 | 0 | 10 |

| 3 | 15 | 4 | 19 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Category | |||

| None | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Mild | 6 | 2 | 13 |

| Type 2 ROP | 10 | 2 | 15 |

| Treatment-requiring | 6 | 2 | 12 |

| APROP | 2 | 0 | 8 |

ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; APROP, aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity.

Consensus Reference Standard Diagnosis

For each clinical case presented in the tele-education program, a consensus reference standard ROP diagnosis was established. Ryan and colleagues40 previously described this method, which was done by combining the clinical diagnosis and the image reading by multiple experienced readers, as follows:

The clinical diagnosis (based on complete ophthalmic examination and indirect ophthalmoscopy by an experienced ROP examiner) is recorded.

Each set of retinal images is interpreted by three experienced readers using a Web-based system.

The image-based diagnosis (plus disease, zone, stage, category, APROP) that is selected by the majority of image readers is then compared to the clinical diagnosis. When these two diagnoses are the same, this is defined as the consensus reference standard diagnosis. When the diagnoses are different, all of the data are reviewed by two of the investigators (R.V.P.C, M.F.C.), along with two study coordinators (K.E.J., S.O.), and a consensus reference standard is determined. This consensus reference standard diagnosis is then used for the purposes of this current study.

Pretest

To determine a baseline level of competency in ROP diagnosis, each trainee completed a pretest of 20 clinical cases with various degrees of ROP pathology. Sixteen (80%) of 20 were unique cases, and 4 (20%) of 20 cases were repeated to measure for intra-grader reliability. The pretest was untimed, and trainees were not required to complete the pretest in one sitting. Trainees were not provided with any tutorial material for ROP diagnosis during the pretest. Although the trainees were able to review previous answers to clinical cases within the pretest once the case was complete, they were not allowed to change their responses once a case was complete and submitted. No immediate feedback was provided after completion of the pretest, and the trainees were not made aware of correct or incorrect responses.

Retinopathy of Prematurity Tutorial

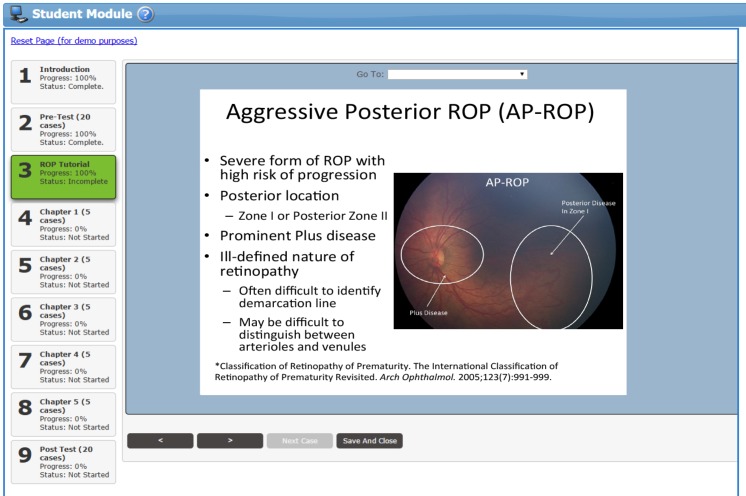

After completion of the pretest, trainees were given access to a tutorial on ROP diagnosis and management that was designed by the coauthors (R.V.P.C., S.N.P., K.E.J., S.O., A.D.P., M.F.C.) (Figure 2). The ROP tutorial included didactic information on the different classifications of ROP diagnosis (plus disease, zone, stage, category, APROP) and pertinent management considerations (treatment, follow-up time). When trainees were in between different chapters, the ROP tutorial was available as a reference for clarification, but the tutorial was not available while trainees were in the pretest, within a training chapter section, or in the posttest.

FIGURE 2.

Educational material within the tutorial on retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) diagnosis. Individual slides were developed by the coauthors for different classifications of ROP diagnosis (plus, zone, stage, category, aggressive posterior ROP) and pertinent management considerations (treatment, follow-up time). Color fundus photographs included in the tutorial were annotated to highlight relevant findings. References to articles on ROP classification criteria and management considerations were provided to the trainees for additional information.

Retinopathy of Prematurity Training Chapters

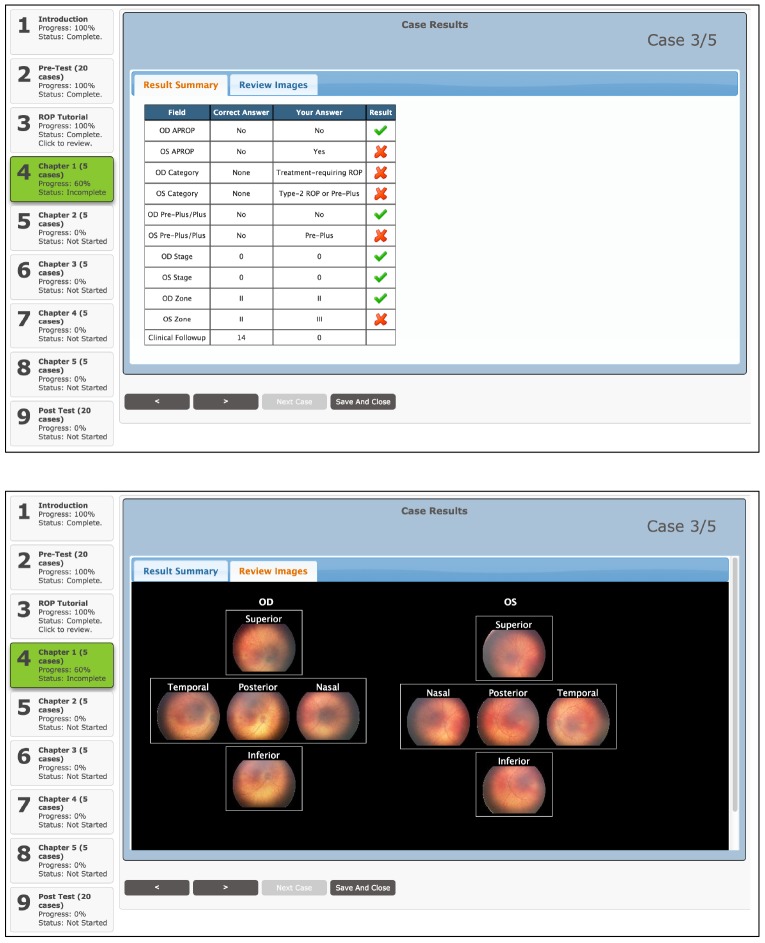

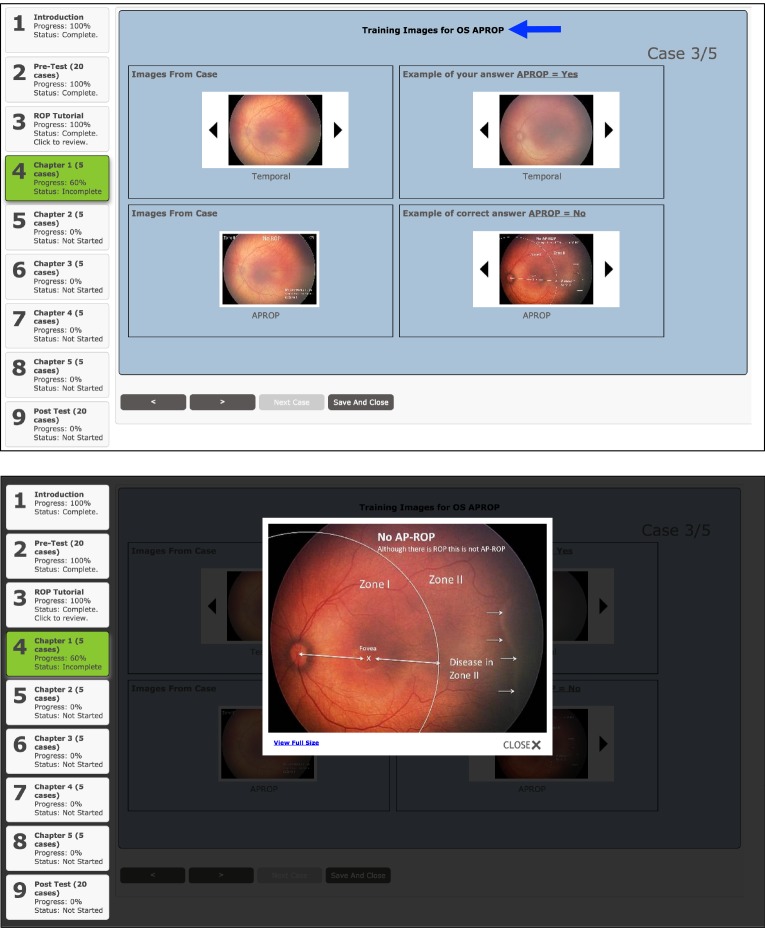

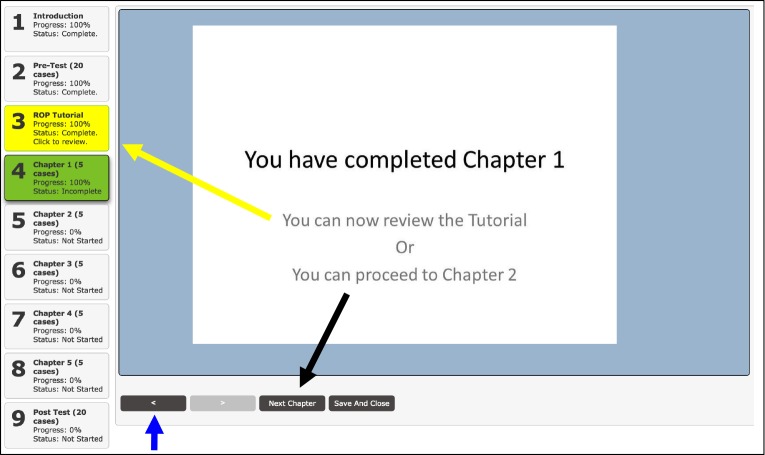

After completing the ROP tutorial, trainees were asked to complete five training chapters, each consisting of five clinical cases, for a total of 25 clinical cases. Each training chapter was designed to emphasize a particular category of ROP (no/mild ROP, type 2 ROP, and treatment-requiring ROP). In a given training chapter, once trainees completed a clinical case, they would be provided the correct answer for each aspect of the diagnosis (plus disease, zone, stage, category, APROP) (Figure 3). For each incorrect response, the trainees would receive feedback in four ways: (1) review of the original images from the clinical case; (2) annotated images from the clinical case that outline the specific pathology; (3) additional annotated images of the correct answer from different clinical cases that are in our ROP image repository; and (4) images from the ROP image repository that contain examples of the incorrect pathology in the trainee’s response (Figure 4). After reviewing the feedback generated by the tele-education system, trainees could then proceed to the next clinical case within the training chapter. After completing the training chapter, trainees had the option to (1) proceed to the next chapter or section, (2) review the ROP tutorial, or (3) review their responses and feedback from previous training chapters. They would not, however, have access to the pretest (Figure 5).

FIGURE 3.

Case results after completion of the clinical case within the training chapter section of the retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) tele-education system. Top, Trainees were given immediate feedback on which aspects of their ROP diagnosis (plus, zone, stage, category, aggressive posterior ROP) were correct and incorrect. They were shown both their answer and the correct answer. Bottom, Trainees were able to review all available images from the preceding case in the case results section.

FIGURE 4.

Feedback section after viewing case results within the chapter section of the retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) tele-education system. Top, For each aspect of the trainee’s incorrect ROP diagnosis (plus, zone, stage, category, aggressive posterior ROP) from the clinical case, a feedback section was generated from an educational repository of annotated images along with images from the clinical case that was just completed. Images from the case were annotated in this section to outline specific pathology that the trainee should have recognized to make the correct diagnosis. For incorrect answers, the dynamic feedback section also included examples of the incorrect response to help the trainees differentiate similar diagnoses. This feedback section was repeated for each aspect of the incorrect ROP diagnosis in each eye (blue arrow). Bottom, Images within the feedback section could also be selected to generate a larger-resolution image for better display.

FIGURE 5.

Trainee options after completing a training chapter section of the retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) tele-education program. After trainees completed the 5 clinical cases within a training chapter, they were able to (1) re-review the cases from current chapter (blue arrow); (2) refer back to the ROP tutorial (yellow arrow and yellow box); (3) proceed to the next chapter (black arrow); or (4) save their results and exit the program.

Posttest

After completion of the five ROP training chapters, trainees were directed to complete a posttest that was identical to the pretest (same 20 clinical cases as the pretest but in a different order). The trainees were unable to access other sections of the tele-education program (pretest, ROP tutorial, and training chapters), but were able to review answers from previous clinical cases within the posttest in a similar fashion as was allowed during the pretest. Once the posttest was complete, trainees were unable to reenter the tele-education system. No immediate feedback was provided after completion of the posttest, and the trainees were not made aware of correct or incorrect responses immediately after the posttest.

SURVEY OF TRAINEES REGARDING EFFECTIVENESS OF TELE-EDUCATION SYSTEM

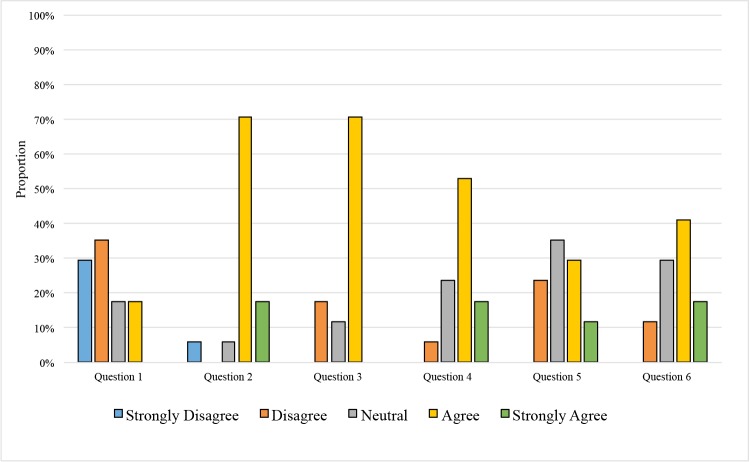

A Web-based survey was created using a publicly available service (http://www.surveymonkey.com). Items in existing psychometric instruments were adapted to measure trainees’ attitudes by six question items using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree)41–44; one additional question allowed for free-text comments. Questions were reviewed by the authors (A.K.L., K.E.J., M.F.C., R.V.P.C.) for face validity and content validity and modified until all authors were satisfied with the survey instrument. There were a total of six survey items, consisting of two items that assessed the trainees’ perception of their understanding of the diagnosis of ROP, three items that assessed the trainees’ attitudes toward preferred learning environment, and one item that assessed the trainees’ opinion of ease of use of the ROP tele-education system. A link to the survey was sent to all trainees who completed the ROP tele-education program. Those who did not complete the survey within 1 month were sent a follow-up email reminder.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The diagnostic accuracy for ROP by the trainees was evaluated using sensitivity and specificity as compared to the consensus reference standard diagnosis. Sensitivity was defined as the ability to accurately detect a specific category of ROP when disease was present, and specificity was defined as the ability to accurately identify when a specific category of ROP was not present. For sensitivity and specificity calculations, the cutoff values that were investigated included stage 1 disease or worse, stage 2 disease or worse, stage 3 disease or worse, zone I or II disease, zone I disease, pre-plus or worse, plus disease, mild or worse disease, type 2 ROP or worse disease, treatment-requiring disease, and the presence of APROP. All data were analyzed using statistical software (Stata/SE 12.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

Pre-ROP and post-ROP tele-education program sensitivities and specificities were compared using the paired t test for each training year and for all trainees as a single cohort. Trends in performance for the training chapter–based cases were analyzed using logistic regression. At each cutoff value, logistic regression was used to obtain the odds ratio of having a “positive” diagnosis as more diagnoses were performed. For cases of no disease, an odds ratio of <1 would mean that “positive” responses were less likely as more diagnoses were performed (ie, improved specificity). For cases of disease, odds ratio of >1 would mean that “positive” responses were more likely as more diagnoses were performed (ie, improved sensitivity). For both the paired t test and logistic regression, statistical significance was considered to be a 2-sided P value <.05.

Based on the four cases that were repeated in both the pretest and posttest, intra-grader reliability was evaluated using the kappa (κ) statistic for chance-adjusted agreement in diagnosis. Specifically, pre-ROP and post-ROP tele-education program unweighted kappas were calculated for the trainees on the diagnosis of plus disease, zone, stage, category, APROP, and the presence of ROP of any severity. A well-known scale was used for interpretation of results: 0 to 0.20, slight agreement; 0.21 to 0.40, fair agreement; 0.41 to 0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61 to 0.80, substantial agreement; and 0.81 to 1.00, almost-perfect agreement.6

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the trainees’ responses to the post-ROP tele-education program Web-based survey. The nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the trainees’ pre-ROP and post-ROP tele-education program perception of their understanding of the diagnosis of ROP. Again, statistical significance was considered to be a 2-sided P value <.05.

RESULTS

SUMMARY OF OPHTHALMOLOGY RESIDENCY TRAINING PROGRAM AND TRAINEE CHARACTERISTICS

Tables 2 and 3 summarize key characteristics of the ophthalmology residency programs and the ophthalmology residents involved in this study. Fifty-five ophthalmology residents from five programs were given access to the ROP tele-education program, Forty-six residents started the pretest, and 31 residents (56%) completed the program. Of the trainees that completed the ROP tele-education program, 15 (48%) were PGY-2 residents, 7 (23%) were PGY-3, and 9 (29%) were PGY-4. On average, there are 380 ROP examinations performed per year at each residency. None of the ophthalmology residency programs involved in the study had a formal ROP curriculum, which was defined as having a standardized way of teaching ROP to the residents and assessment of competency for ROP diagnosis and management.

TABLE 2.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE 5 OPHTHALMOLOGY RESIDENCY PROGRAMS PARTICIPATING IN THE ROP TELE-EDUCATION SYSTEM

| ROP curriculum, n | 0 |

| Access to RetCam, n | 4 |

| ROP exams per year performed by faculty | |

| Mean ± SD (range) | 380 ± 26 (350–400) |

| Number of trainees (n=31) from each residency program participating in the ROP tele-education program, n | |

| Residency program A | 19 |

| Residency program B | 7 |

| Residency program C | 1 |

| Residency program D | 1 |

| Residency program E | 3 |

| Residency program size by number of residents per year, n | |

| ≤2 residents/year | 0 |

| 3–4 residents/year | 2 |

| ≥5 residents/year | 3 |

ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

TABLE 3.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE 31 OPHTHALMOLOGY RESIDENTS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE ROP TELE-EDUCATION SYSTEM

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD (range) | 30.9 ± 3 (26–43) |

| Gender | |

| Male, n (%) | 20 (66) |

| Female, n (%) | 11 (34) |

| Training year (PGY) | |

| PGY-2, n (%) | 15 (48) |

| PGY-3, n (%) | 7 (23) |

| PGY-4, n (%) | 9 (29) |

PGY, post graduate year; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY OF TRAINEES FOR RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY BEFORE AND AFTER PARTICIPATION IN THE TELE-EDUCATION PROGRAM

Tables 4 through 7 summarize pre-ROP and post-ROP tele-education program accuracy of ROP diagnosis in terms of trainees’ sensitivity and specificity for detecting certain levels of disease severity.

TABLE 4.

ACCURACY OF ROP DIAGNOSIS IN THE PRETEST AND POSTTEST BY THE 15 PGY-2 TRAINEES WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE ROP TELE-EDUCATION PROGRAM

| DIAGNOSIS | SENSITIVITY, % (SE) | SPECIFICITY, % (SE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRETEST | POSTTEST | P VALUE | PRETEST | POSTTEST | P VALUE | |

| Stage | ||||||

| Stage 1 or worse | 85 (4) | 95 (1) | P=.007* | 55 (10) | 91 (4) | P=.008* |

| Stage 2 or worse | 73 (5) | 94 (2) | P<.001* | 66 (10) | 94 (1) | P=.014* |

| Stage 3 or worse | 55 (6) | 73 (5) | P=.009* | 80 (6) | 91 (2) | P=.072 |

| Zone | ||||||

| Zone I or II | 70 (5) | 92 (3) | P<.001* | . . .† | . . .† | . . .† |

| Zone I | 42 (9) | 72 (8) | P=.009* | 72 (5) | 86 (3) | P=.034* |

| Plus | ||||||

| Pre-plus or worse | 67 (7) | 78 (5) | P=.040* | 67 (10) | 95 (1) | P=.019* |

| Plus | 36 (11) | 53 (7) | P=.060* | 85 (4) | 92 (2) | P=.113 |

| Category | ||||||

| Mild or worse | 88 (2) | 95 (1) | P=.013* | 55 (11) | 91 (4) | P=.011* |

| Type 2 or worse | 65 (7) | 79 (5) | P=.016* | 72 (8) | 89 (2) | P=.033* |

| Treatment-requiring | 29 (8) | 69 (7) | P<.001* | 81 (5) | 89 (2) | P=.111 |

| Presence APROP | 40 (13) | 67 (11) | P=.217 | 78 (7) | 94 (2) | P=.046* |

| Presence ROP | 85 (4) | 95 (1) | P=.007* | 55 (10) | 91 (4) | P=.008* |

PGY, post graduate year; APROP, aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

Statistically significant (P<.05) using paired t test.

Specificity is undefined as all eyes contained disease in zone I and/or zone II.

TABLE 7.

ACCURACY OF ROP DIAGNOSIS IN THE PRETEST AND POSTTEST BY ALL 31 TRAINEES WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE ROP TELE-EDUCATION PROGRAM

| DIAGNOSIS | SENSITIVITY, % (SE) | SPECIFICITY, % (SE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRETEST | POSTTEST | P VALUE | PRETEST | POSTTEST | P VALUE | |

| Stage | ||||||

| Stage 1 or worse | 90 (2) | 96 (1) | P=.004* | 75 (6) | 87 (3) | P=.111 |

| Stage 2 or worse | 82 (3) | 96 (1) | P<.001* | 79 (5) | 92 (1) | P=.027* |

| Stage 3 or worse | 60 (4) | 78 (3) | P<.001* | 87 (3) | 92 (1) | P=.127 |

| Zone | ||||||

| Zone I or II | 65 (3) | 89 (2) | P<.001* | . . .† | . . .† | . . .† |

| Zone I | 44 (7) | 74 (5) | P<.001* | 84 (3) | 90 (2) | P=.112 |

| Plus | ||||||

| Pre-plus or worse | 69 (4) | 81 (3) | P=.003* | 81 (5) | 95 (2) | P=.028* |

| Plus | 49 (8) | 67 (5) | P=.016* | 89 (2) | 92 (1) | P=.235 |

| Category | ||||||

| Mild or worse | 91 (1) | 95 (1) | P=.007* | 74 (6) | 87 (3) | P=.105 |

| Type 2 or worse | 70 (4) | 84 (3) | P<.001* | 81 (4) | 89 (1) | P=.054 |

| Treatment- requiring | 48 (7) | 78 (4) | P<.001* | 85 (3) | 90 (1) | P=.103 |

| Presence APROP | 35 (9) | 77 (6) | P=.003* | 86 (4) | 94 (1) | P=.051 |

| Presence ROP | 90 (2) | 96 (1) | P=.004* | 75 (6) | 87 (3) | P=.111 |

APROP, aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

Statistically significant (P<.05) using paired t test.

Specificity is undefined as all eyes contained disease in zone I and/or zone II.

When all training years are considered together as one group, after taking the ROP tele-education program, there was a statistically significant improvement in the accuracy of ROP diagnosis for plus, zone, stage, category, and APROP. The largest increase in sensitivity was observed for the diagnosis of APROP, which saw a 42-percentage point increase (P=.003). The smallest increase in sensitivity was observed for the detection of mild or worse ROP, which saw a 4-percentage point increase (P=.007). Again considering all training years together, statistically significant changes in specificity were only observed for the detection of stage 2 or worse disease (P=.027) and for the detection of pre-plus or worse disease (P=.028).

When each training year was analyzed independently, increases in sensitivity were observed, although the results were not always statistically significant. In general, only PGY-2 trainees demonstrated increased specificity for detecting certain levels of disease following completion of the tele-education program. PGY-3 and PGY-4 trainees either did not show improved specificity or demonstrated small, but statistically insignificant, decreases.

In diagnosis of clinically significant disease (type 2 ROP or worse and treatment-requiring ROP), when comparing the results of the pretest to the posttest, there was near-universal improvement in accuracy of diagnosis by each of the groups (PGY-2, PGY-3, and PGY-4) independently. However, there was significant variability in the diagnosis of type 2 ROP or worse and treatment-requiring ROP within each PGY group. The mean (range) posttest sensitivity for detecting type 2 or worse was 0.79 (0.31–1.00) for PGY-2, 0.86 (0.75–1.00) for PGY-3, and 0.90 (0.75–1.00) for PGY-4 trainees. In detecting treatment-requiring disease, the mean (range) posttest sensitivity was 0.69 (0.17–1.00) for PGY-2, 0.88 (0.50–1.00) for PGY-3, and 0.87 (0.67–1.00) for PGY-4. Specificity for treatment-requiring ROP demonstrated a lesser degree of variability. The mean (range) posttest specificity for treatment-requiring disease was 0.89 (0.69–1.00) for PGY-2, 0.91 (0.85–1.00) for PGY-3, and 0.91 (0.85–1.00) for PGY-4 trainees.

Comparisons in accuracy of diagnosis of ROP were also evaluated between the PGY-2, PGY-3, and PGY-4 groups to determine if accuracy of ROP diagnosis was affected by level of residency training year. When comparing performance between training years, accuracy of diagnosis of plus disease was found to be significantly different among the training years (P=.008). Fisher least-significant-difference post hoc analysis showed a statistically significant difference in sensitivity of diagnosis of plus disease when the PGY-2 group was compared to either the PGY-3 or the PGY-4 group (Table 8).

TABLE 8.

COMPARISON OF ACCURACY OF ROP DIAGNOSIS IN THE POSTTEST BETWEEN RESIDENCY TRAINING YEARS

| DIAGNOSIS | SENSITIVITY, % (SE) | P VALUE |

COMPARISON GROUP |

POST

HOC P VALUE |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| PGY2 | PGY3 | PGY4 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Stage 3 or worse | 73 (5) | 79 (4) | 84 (3) | P=.201 | . . . | . . . |

| Zone I | 72 (8) | 82 (9) | 72 (7) | P=.674 | . . . | . . . |

| PGY2 vs PGY3 | P=.018† | |||||

| Plus | 53 (7) | 79 (8) | 81 (5) | P=.008* | PGY2 vs PGY4 | P=.005† |

| PGY3 vs PGY4 | P=.795 | |||||

| Type 2 or worse | 79 (5) | 86 (3) | 90 (3) | P=.237 | . . . | . . . |

| Treatment-requiring | 69 (7) | 88 (7) | 87 (5) | P=.087 | . . . | . . . |

| . . . | . . . | |||||

| Presence APROP | 67 (11) | 86 (9) | 89 (11) | P=.281 | . . . | . . . |

| . . . | . . . | |||||

PGY, post graduate year; APROP, aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

Statistically significant (P<.05) using one-way analysis of variance.

Statistically significant (P<.05) using the Fisher least significant difference.

ASSESSMENT OF IMPROVEMENT IN DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY OF RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY FOR TRAINEES

For the 25 training cases in the five training chapters, logistic regression analysis was performed to assess if there was any significant change in improvement as trainees progressed through the training chapters. If all trainees were taken together as one group, improved accuracy of ROP diagnosis was demonstrated as the trainees progressed from the beginning of the first training chapter to completion of the fifth training chapter, and there were statistically significant trends for increased sensitivity across all levels of disease. Statistically significant trends for decreased specificity were observed for the detection of stage 3 or worse disease (P<.001), plus disease (P<.001), type 2 ROP or worse disease (P=.007), and APROP (P<.001). Statistically significant trends for increased specificity were observed for the detection of stage 1 or worse disease (P=.012), zone I disease (P=.05), mild or worse disease (P=.017), and the detection of any degree of ROP (P=.012) (Table 9).

TABLE 9.

ACCURACY OF ROP DIAGNOSIS IN THE TRAINING CHAPTERS BY ALL 31 TRAINEES WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE ROP TELE-EDUCATION PROGRAM

| DIAGNOSIS | SENSITIVITY, % (SE) | SPECIFICITY, % (SE) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHAPTER | CHAPTER | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | P VALUE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | P VALUE | |

| Stage | ||||||||||||

| Stage 1 or worse | 73 (3) | 63 (4) | 97 (1) | 100 (0) | 98 (1) | P<.001* | 65 (7) | 66 (5) | . . .† | . . .† | 82 (6) | P=.012* |

| Stage 2 or worse | 98 (2) | 34 (7) | 98 (1) | 98 (1) | 88 (3) | P<.001* | 83 (3) | 87 (2) | 45 (8) | . . .† | 87 (3) | P=.470 |

| Stage 3 or worse | 44 (7) | . . .‡ | 55 (4) | 88 (3) | 87 (5) | P<.001* | 91 (2) | 96 (1) | 59 (6) | 27 (6) | 78 (2) | P<.001* |

| Zone | ||||||||||||

| Zone I or II | 74 (4) | 80 (3) | 98 (1) | 99 (1) | 86 (3) | P<.001* | . . .† | . . .† | . . .† | . . .† | . . .† | |

| Zone I | 45 (6) | . . .‡ | 73 (7) | 82 (4) | 87 (6) | P<.001* | 81 (4) | 89 (3) | 81 (3) | 56 (8) | 94 (2) | P=.050* |

| Plus | ||||||||||||

| Pre-plus or worse | 60 (6) | . . .‡ | 71 (4) | 95 (3) | 80 (4) | P<.001* | 89 (2) | 95 (2) | 44 (6) | . . .† | 89 (3) | P=.099 |

| Plus | 13 (6) | . . .‡ | . . .‡ | 75 (4) | 97 (3) | P<.001* | 97 (1) | 100 (0) | 79 (3) | 51 (7) | 98 (1) | P<.001* |

| Category | ||||||||||||

| Mild or worse | 72 (3) | 63 (3) | 95 (2) | 100 (0) | 96 (2) | P<.001* | 65 (7) | 64 (5) | . . .† | . . .† | 81 (6) | P=.017* |

| Type 2 or worse | 65 (6) | . . .‡ | 77 (4) | 95 (3) | 93 (3) | P<.001* | 95 (2) | 94 (2) | 19 (7) | . . .† | 89 (3) | P=.007* |

| Treatment-requiring | 29 (8) | . . .‡ | . . .‡ | 84 (4) | 94 (4) | P<.001* | 90 (2) | 98 (1) | 74 (4) | 39 (9) | 96 (2) | P=.142 |

| Presence APROP | . . .‡ | . . .‡ | . . .‡ | 49 (4) | 73 (7) | P=.001* | 97 (1) | 99 (1) | 96 (1) | 59 (7) | 98 (1) | P<.001* |

| Presence ROP | 73 (3) | 63 (4) | 97 (1) | 100 (0) | 98 (1) | P<.001* | 65 (7) | 66 (5) | . . .† | . . .† | 82 (6) | P=.012* |

APROP, aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

Statistically significant (P<.05) using logistic regression.

Specificity is undefined as there were no condition negative eyes.

Sensitivity is undefined as there were no condition positive eyes.

When the PGY groups were analyzed independently, similar trends were observed where there was improvement in the accuracy of diagnosis for ROP as the trainees progressed through the training chapters. However, there were fewer statistically significant results. The PGY-2 trainees demonstrated statistically significant trends for increased sensitivity across all disease levels with the exception of the detection of disease in zone I or II (P=.185). For PGY-3 trainees, statistically significant trends for increased sensitivity were observed for the detection of stage 1 or worse (P<.001), stage 3 or worse (P<.001), zone I or II (P<.001), zone I (P<.001), plus disease (P<.001), mild or worse (P<.001), type 2 ROP or worse (P<.001), treatment-requiring ROP (P=.004), and the detection of any degree of ROP (P<.001). For PGY-4 trainees, statistically significant trends for increased sensitivity were observed for the detection of stage 1 or worse (P<.001), stage 3 or worse (P<.001), zone I or II (P<.001), zone I (P=.004), pre-plus or worse (P=.001), plus disease (P=<.001), mild or worse (P<.001), type 2 ROP or worse (P=.007), treatment-requiring ROP (P=.001), and the detection of any degree of ROP (P<.001). There were statistically significant trends for decreased specificity for PGY-2 trainees for the diagnosis of stage 3 or worse disease (P<.001), plus disease (P=.001), and APROP (P<.001). PGY-2 trainees also demonstrated statistically significant trends for increased specificity for the diagnosis of stage 1 or worse disease (P=.010), zone I disease (P=.032), mild or worse disease (P=.007), and the detection of ROP of any severity (P=.010). For PGY-3 trainees, statistically significant trends for decreased specificity were observed for the diagnosis of stage 3 or worse disease (P<.001), plus disease (P=.023), and the detection of APROP (P=.005). PGY-4 trainees demonstrated statistically significant trends for decreased specificity for the diagnosis of stage 3 or worse disease (P<.001), plus disease (P=.034), and the diagnosis of type 2 ROP or worse disease (P<.001). Neither PGY-3 nor PGY-4 trainees demonstrated any statistically significant trends for an increase in specificity when analyzing results from the 25 training cases.

INTRA-GRADER AGREEMENT IN DIAGNOSIS OF RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY

Table 10 summarizes intra-grader agreement using Cohen’s κ statistic. Analyzing all training years together, pretest values for κ ranged from 0.44 for the diagnosis of APROP to 0.80 for the diagnosis of any degree of ROP, indicating that there was moderate to substantial intra-grader reliability. The largest increase was observed for the diagnosis of stage, which saw an increase of 0.25. Of note, there was a decrease in intra-grader reliability for the diagnosis of APROP, which saw a decrease of 0.07.

TABLE 10.

KAPPA STATISTICS FOR INTRA-GRADER AGREEMENT AMONG ALL 31 TRAINEES IN THE PRETEST AND POSTTEST OF THE ROP TELE-EDUCATION PROGRAM

| DIAGNOSIS | COHEN’S κ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGY-2 | PGY-3 | PGY-4 | ALL TRAINEES | |||||

| PRETEST | POSTTEST | PRETEST | POSTTEST | PRETEST | POSTTEST | PRETEST | POSTTEST | |

| Stage | 0.36 | 0.78 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.49 | 0.74 |

| Zone | 0.40 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.59 |

| Plus | 0.49 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.68 |

| Category | 0.48 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.64 |

| Presence APROP | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.74 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.37 |

| Presence ROP | 0.73 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.87 |

PGY, post graduate year; APROP, aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

POST–RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY TELE-EDUCATION PROGRAM SURVEY OF TRAINEES

Seventeen (55%) of the 31 trainees who completed the ROP tele-education program also completed the post-program survey. Figure 6 shows the results of this survey. With a maximum score of 5 for each question, the average score for each question was calculated. The average score for question 1 was 2.24, as 11 (65%) of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that they had an adequate understanding of the diagnosis of ROP before taking the ROP tele-education program. The respondents’ score for question 4 showed a statistically significant improved understanding of ROP, with an average score of 3.82, after completing the training (signed rank test; P<.001). Twelve (71%) of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they had an adequate understanding of the diagnosis of ROP after completing the ROP tele-education program. The average score for question 2 was 3.94 as 15 (88%) of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the ROP tele-education system was easy to use. Twelve (71%) of the respondents agreed that the feedback at the end of cases was helpful. For question 6, the average score was 3.65 as 10 (59%) of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they learned more effectively with the automatic feedback opposed to textbook learning.

FIGURE 6.

Survey results of trainees who completed the retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) tele-education program (N=17). Survey questions after completion of the ROP tele-education program were rated using a Likert scale of “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The questions included in the survey were: (1) “I had an adequate understanding of the diagnosis of ROP before taking the pretest in the ROP Student Module.” (2) “The ROP Student Module was easy to use.” (3) “I learned from the feedback provided at the end of each case.” (4) “I had an adequate understanding of the diagnosis of ROP after completing the ROP Student Module.” (5) “I learn more effectively in a Web-based environment compared to a traditional textbook format.” and (6) “I learned more effectively from ROP cases with automatic feedback compared to a traditional textbook format.”

DISCUSSION

SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS

This study evaluates the ability of a novel ROP tele-education system to improve accuracy of image-based ROP diagnosis by ophthalmology residents. The key findings from this study are as follows:

This ROP tele-education system successfully improved the ability of ophthalmology residents to recognize and accurately diagnose ROP.

Diagnosis of plus disease was significantly better for PGY-3 and PGY-4 residents than for PGY-2 residents after taking the ROP tele-education program.

Accuracy of diagnosis of ROP improved as the trainees progressed through more training chapters.

Intra-grader agreement, as determined by the κ statistic, improved for identification of plus disease, zone, stage, and category of ROP after completion of the ROP tele-education program.

Trainees felt that their understanding of the diagnosis of ROP improved after participating in the ROP tele-education program. In addition, they found the ROP tele-education system easy to use, and they felt that they learned more effectively from ROP cases with automatic feedback compared to a traditional textbook format.

IMPROVED DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY FOR RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY

The first key finding is that the Web-based tele-education system, which provides automatic feedback of clinical ROP cases using digital images, is effective in improving diagnostic accuracy of ROP by ophthalmology residents. In our study, there was improvement in sensitivity for all categories of ROP diagnosis when analyzing all of the trainees together as a single group. There were statistically significant improvements between diagnostic accuracy of clinically significant ROP (type 2 ROP or worse and treatment-requiring ROP) from the pretest to the posttest, indicating that the tele-education system does improve performance.

To determine if level of training and more experience in ophthalmology had any influence on diagnostic accuracy of trainees after taking the tele-education program, we compared performance between training years. As a result, our second key finding is that for certain categories of ROP, such as plus disease, experience in ophthalmology may play a role in the ability for a trainee to learn and recognize relevant features of the condition. This has significant clinical implications given that plus disease is a hallmark for the diagnosis of treatment-requiring ROP, and failure to recognize plus disease appropriately can lead to irreversible blindness due to progression of ROP.

These findings of accuracy of diagnosis for ROP being dependent on physician experience are not unique to our current study. Previous studies published by our group,12,13 which examined the accuracy of pediatric ophthalmology and retina fellows in image-based ROP diagnosis and management, also demonstrated that experience matters for the accurate diagnosis of ROP. The performance in ROP diagnosis of pediatric ophthalmology and retina fellows was compared to that of two experienced retina specialists, and it was shown that the fellows have less diagnostic accuracy in identifying clinically significant disease. Pediatric ophthalmology fellows were found to have low diagnostic sensitivity for detecting both type 2 or worse and treatment-requiring ROP. For the detection of type 2 ROP or worse, pediatric ophthalmology fellows demonstrated a mean (range) sensitivity of 0.527 (0.356–0.709) and a mean (range) specificity of 0.938 (0.777–1.000).12 For the diagnosis of treatment-requiring ROP, the mean (range) sensitivity of the pediatric ophthalmology fellows was 0.516 (0.267–0.765) and mean (range) specificity was 0.949 (0.805–1.000).12 Similarly, in a study of retina fellows, the accuracy of retina fellows for image-based ROP diagnosis was shown to be variable for clinically significant disease. For detection of type 2 or worse ROP, mean (range) sensitivity by retina fellows was 0.751 (0.512–0.953) and specificity was 0.841 (0.707–0.976).13 For detection of treatment-requiring ROP, mean (range) sensitivity was 0.914 (0.667–1.000) and specificity was 0.871(0.678–0.987).13

In comparing the performance of the ophthalmology residents in this current study to the pediatric ophthalmology and retina fellows in the previous published studies by our group,12,13 we found that at a minimum, the residents perform as well as, and in some cases better than, fellows who have undergone additional training but did not take a ROP tele-education program. The specific findings of this comparison are as follows: (1) the ophthalmology residents performed better than the pediatric ophthalmology fellows with the exception of the PGY-2 residents in diagnosing treatment-requiring ROP; (2) there was no statistically significant difference between the residents and the retina fellows in diagnosing type 2 ROP or worse and treatment-requiring ROP, with the exception of PGY-4 residents outperforming the retina fellows on the diagnosis of type 2 ROP or worse (P=.048); and (3) when all of the fellows are considered together (pediatric ophthalmology and retina fellows combined), the sensitivity for the diagnosis of type 2 ROP or worse is significantly higher for the residents than the fellows, and there is no statistically significant difference for the sensitivity of diagnosing treatment-requiring ROP (Table 11). When comparing the specificity of the residents to that of the fellows and the two experienced retina specialists, there were no statistically significant differences for the diagnosis of either type 2 ROP or worse and treatment-requiring ROP. This finding was consistent across all training years and fellowship types. We also performed a comparison of performance of the ophthalmology residents to the accuracy of ROP diagnosis among an experienced retinal specialist from our previous studies.13 Through this analysis, the posttest sensitivities and specificities for the diagnosis of clinically significant disease by the ophthalmology residents in this current study showed no statistically significant difference compared to that of these retinal specialists.13

TABLE 11.

COMPARISON OF ACCURACY OF ROP DIAGNOSIS BY ALL TRAINEES THAT COMPLETED THE ROP TELE-EDUCATION PROGRAM AGAINST OPHTHALMOLOGY FELLOWS AND RETINA SPECIALISTS*

| DIAGNOSIS |

TRAINING YEAR |

P VALUE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TRAINEES

VS RETINA SPECIALISTS |

TRAINEES

VS RETINA FELLOWS |

TRAINEES

VS PEDIATRIC OPHTHALMOLOGY FELLOWS |

TRAINEES

VS ALL FELLOWS |

||

| Type 2 or worse | PGY-2 | P=.520 | P=.609 | P=.008† | P=.073 |

| PGY-3 | P=.681 | P=.183 | P<.001† | P=.020† | |

| PGY-4 | P=.839 | P=.048 | P <.001† | P=.003† | |

| All trainees | P=.665 | P=.176 | P <.001† | P=.002† | |

| Treatment-requiring | PGY-2 | P=.139 | P=.052 | P=.216 | P=.572 |

| PGY-3 | P=.416 | P=.697 | P=.010† | P=.252 | |

| PGY-4 | P=.237 | P=.517 | P=.003† | P=.216 | |

| All trainees | P=.215 | P=.171 | P=.023† | P=.658 | |

PGY, post graduate year; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

P values were calculated by comparing the trainees’ posttest sensitivities for the diagnosis of type 2 or worse and treatment-requiring ROP to data previously published by our group that examined the accuracy of retina specialists, retina fellows, and pediatric ophthalmology fellows for the diagnosis of type 2 or worse and treatment-requiring ROP.12,13

Statistically significant (P<.05) using the Student t test.

The third key finding is that performance by the trainees for the accurate diagnosis of ROP improved as they progressed through more training chapters. When performing a logistic regression analysis of the performance by the ophthalmology residents in the training chapters, we found that there was improvement in sensitivity for all categories of disease and a decrease in specificity for stage 3 or worse, plus disease, type 2 ROP or worse, and APROP. The improvement in sensitivity and decrease in specificity are consistent with the performance of the fellows in other studies who also showed similar trends as more diagnoses were made.13

Therefore, after taking the Web-based ROP tele-education program, it appears that the trainees who participated in the program performed similarly on image-based ROP diagnosis as pediatric ophthalmology fellows, retina fellows, and two experienced retina specialists. This has important implications given that general ophthalmologists have been shown to be involved with ROP screening.14 In order to provide greater access to care for ROP, we will need qualified ophthalmologists who can provide an accurate diagnosis of the disease. A ROP training program that can improve diagnostic accuracy for general ophthalmologists that is comparable to experienced retina specialists would be of significant utility to improving ROP care.

IMPROVED INTRA-GRADER AGREEMENT OF RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY DIAGNOSIS

In addition to accuracy of diagnosis, reliability in diagnosis is critical for the clinical care of neonates at risk of developing ROP. The current policy statement for examination of at-risk infants for ROP recommends treatment of type 1 ROP within 72 hours of diagnosis.45–49 Therefore, evaluation of ROP is extremely time-sensitive, and if an examiner is inaccurate or inconsistent in diagnosis, ROP may progress without appropriate follow-up, leading to blinding disease.

The fourth key finding in this study is that intra-grader agreement, as determined by the κ statistic, improved from moderate to substantial agreement for identification of plus disease, stage, and category of ROP. However, intra-grader agreement decreased from moderate to fair agreement for the diagnosis of APROP. Previous studies by our group have shown that intra-grader reliability can be variable for interpreting different aspects of ROP. Among three experienced retina specialists, near-perfect to perfect agreement was demonstrated, with intra-grader κ of 0.91 to 1.00 for detection of mild or worse ROP at 35 to 37 weeks postmenstrual age, and κ of 0.79 to 1.00 for detection of treatment-requiring ROP at 35 to 37 weeks.6 In a subsequent study,11 we noted a mean (range) intra-grader agreement of plus disease diagnosis by six ROP experts as 0.596 (0.30–1.00), which designates slight to almost-perfect intra-grader agreement.11 Most recently, we demonstrated significant variability in agreement among ROP experts for the diagnosis of APROP.50 The diagnosis of APROP can be challenging even among experienced examiners, and although ICROP includes APROP as a specific form of ROP, the retinal and vascular changes that characterize APROP are still poorly defined.4 It is therefore not surprising that there is variability in intra-grader agreement for APROP diagnosis by the trainees in this study. Despite this decrease in intra-grader agreement, the accuracy of diagnosis for APROP increased for all individual PGY groups with a statistically significant increase in diagnostic performance when looking at all trainees together.

In comparison to intra-grader agreement for the diagnosis of conditions other than ROP, we found that the results of our current study of ophthalmology residents are similar. For example, in age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the κ for intra-grader reliability of fluorescein angiogram interpretation for determining photodynamic therapy eligibility in AMD was found to be 0.44 to 0.89,51 and the intra-grader concordance of fluorescein angiography for detection of classic choroidal neovascularization was 0.66 to 1.00.52

Our findings regarding intra-grader reliability for ROP diagnosis from this and our previously published studies reinforce the fact that there are important subtleties to the diagnosis of clinically significant ROP, which may not be recognized by both trainees and experts in ROP.

HIGH TRAINEE SATISFACTION WITH TELE-EDUCATION AND IMPROVEMENT IN UNDERSTANDING OF RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY DIAGNOSIS

The fifth key finding in this study is that the trainees felt their understanding of the diagnosis of ROP improved after participating in the ROP tele-education program. A previous study we performed also demonstrated similar trends in how trainees felt regarding their understanding of ROP. In a survey of ophthalmology fellows we showed that self-reported competence was dependent on status of fellowship training: three (9%) of 35 retina fellows surveyed and 0 of 16 pediatric ophthalmology fellows felt competent in ROP management after completing their ophthalmology training, whereas 30 (86%) of 35 retina fellows and 13 (81%) of 16 pediatric ophthalmology fellows felt competent in ROP management during their fellowships.18 Despite feeling competent in ROP management during their fellowships, it is still possible that fellows have variable competency in ROP management.12,13 In our current study of ophthalmology residents, not only did the residents feel that they improved, but the results of the posttest analysis demonstrate overall improvement in diagnostic accuracy.

One additional trend noted as a result of the survey administered to the trainees is that the ophthalmology residents preferred to learn through automated feedback and case-based learning. This is not surprising given that most of these trainees were born between 1981 and 1999, which qualifies them as being part of the “millennial generation.” This is a generation who has always had access to mobile phones, computers, and technology that allows them to access information more easily. As a result, the traditional learning model through textbooks is shifting, and there have been significant changes in medical education over the past decade to accommodate this generation of students.53–55 Advances in technology over the past several decades have already altered the traditional apprenticeship model of medical education. In particular, e-learning and Web-based education have become integral components of medical education.56,57 Controversy still remains as to whether e-learning is a better teaching modality than traditional written-based course materials.23

IMPACT ON CLINICAL CARE FOR RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY AND TELEMEDICINE

A tele-education system that can improve diagnostic accuracy for ROP can potentially make an impact from both a socioeconomic and medicolegal perspective by improving the quality of access to care and increasing the number of adequately trained ophthalmologists who can manage ROP. Screening neonates at risk for ROP is of paramount importance for preventing blindness and has repeatedly been shown to be cost-effective in the United States and internationally.58–63 Dave and colleagues63 recently reported that for ROP-related neonatal blindness in Peru, it was estimated that there was a total indirect cost saving at $197,753 per child and a direct cost of laser treatment at $2,496 per child. This translated to an estimated societal lifetime cost saving per child of $195,257 (in USD)

Regardless of the societal cost savings that ROP screening may provide, there are still too few physicians who are willing to provide ROP care. Many ophthalmologists may avoid caring for children with ROP as there are still significant concerns with reimbursement, medicolegal risks, and time to perform ROP examinations in the NICU. From a medicolegal perspective, ROP can lead to significant cost for insurers and medical practitioners, with malpractice claims that can be in the tens of millions of dollars.64 The significant financial awards in ROP malpractice claims have resulted in most malpractice carriers requiring ophthalmologists to increase their personal liability insurance, which comes at a quantifiable cost. In addition, many ophthalmologists are dissuaded from ROP screening because of the complexity of coordinating care and the time involved to provide ROP care.15

Telemedicine is a potential solution to the issues of the increasing societal burden of ROP and the decreasing workforce for the disease. Telemedicine programs have the ability to increase access to care for children in need of ROP screening and may create more efficient ways for physicians to manage patients with ROP. We have previously shown that telemedicine diagnosis is more time-efficient than traditional methods of ROP care.30 Telemedicine for ROP has also been shown to be more cost-effective than examinations by standard indirect ophthalmoscopy. The average costs (in USD) per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained with telemedicine were calculated to be approximately $3,193 compared to $5,617 with indirect ophthalmoscopy.65 Globally, telemedicine programs for ROP have been well established, and the accuracy and reliability of using digital images for ROP diagnosis by both ROP experts and nonexperts has been reported.8,66,67

To ease the ROP burden on ophthalmologists, nonphysicians may be utilized as readers for telemedicine programs.26,68 For many years, nonphysician readers for the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy have been used for clinical trials. In ROP, we can use similar models to those used in diabetic retinopathy screening to train readers for image-based diagnosis of ROP.69–71 One significant advantage in ROP is the well-defined image-based criteria for both diagnosis and management, which makes it well suited for telemedical diagnosis.4,45–49,70 However, given the time-sensitive nature of ROP, it is much more critical than with many other conditions to diagnose and identify disease that requires immediate referral or treatment.

To ensure patient safety, there must be a standardized way to certify readers in ROP telemedicine programs, especially if inexperienced readers or nonophthalmologists are utilized for image-based diagnosis. With the advent of telemedicine for ROP care, tele-education systems would have potential utility to provide training for ophthalmologists who lack experience in ROP diagnosis. Also, as some studies have advocated for nurses and other nonphysician readers to perform initial screening for ROP telemedicine programs, it will be necessary to create more effective methods of education for ROP diagnosis.26,68 A recent study addressing the utility of telemedicine for “acute-phase” ROP included three nonphysician readers to perform ROP diagnosis.26 The readers were “certified” through didactic and image grading training sessions. These methods of certification and training were not well described, and no quantifiable score or outcome was discussed regarding the competency of these nonphysician readers for ROP diagnosis. The tele-education system we have developed has the potential to provide a standardized and quantifiable way to improve competency in image-based ROP diagnosis. It would be useful going forward to have a validated training system for telemedicine providers that may ensure quality and standardization of care for patients at risk for ROP.

IMPACT ON OPHTHALMOLOGY RESIDENCY EDUCATION FOR RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY

Historically, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the Association of University Professors in Ophthalmology have not required or suggested recommendations for ophthalmology residents and pediatric ophthalmology or retina fellows with regard to number of ROP examinations or lasers that would indicate competency with ROP care.72 The ACGME, which provides accreditation to residency programs, exclusively tracked surgical case numbers rather than examination numbers.73 However, our previous study of ROP education at the residency level highlights several areas of deficiency in ROP training, including low exam numbers, inadequate supervision, and resident-fellow competition for ROP cases.16 A number of strategies may be used to improve education for ROP, including a case log system, an observed structured clinical examination performed on actual patients,74 or a certification process based on a combination of these approaches. An alternative approach that does not require the physical presence of an ROP expert involves the use of a digital camera to acquire fundus photographs and then compare the expert’s diagnosis to the trainee’s exam-based diagnosis.13,75

Over a decade ago, the ACGME launched the ACGME Outcome project, which was intended to improve residency education through the teaching and assessment of six core competencies. The six general core competencies include patient care, medical knowledge, professionalism, communication and interpersonal skills, practice-based learning, and systems-based practice.76 However, there was difficulty in measuring outcomes for this project. Therefore, the Milestones Project was subsequently launched in 2008, with the Ophthalmology Milestones Working Group (OMWG) being established thereafter. In much of the framework of the Milestones Project, progression of a trainee is based on the Dreyfus model of expertise acquisition. Trainees are to progress from being a novice to beginner, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and ultimately to expert. Residents should sequentially reach certain milestones during specific times during their residency education, and residency programs will be able to assess resident performance in a more objective manner.77

Given this recent implementation by the ACGME of the Milestones Project, medical educators have sought implementation of new training programs with innovative educational resources that include Web-based learning. Medical and surgical specialties, including pathology,78,79 radiology,24,80,81 internal medicine,82,83 emergency medicine,84,85 general surgery,86–89 and urology,90–92 among others, have all explored the different approaches to incorporating Web-based learning at the resident-physician level. Ophthalmology has also incorporated Web-based learning for trainees. The International Council of Ophthalmology has a Technologies for Teaching and Learning Committee that is exploring ways to integrate technology into ophthalmic education. Additionally, Web resources such as the Atlas of Ophthalmology, EyeWiki, and OphthalmologyWeb are emerging resources that help ophthalmologists-in-training with knowledge acquisition. In particular, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) has developed the Ophthalmic News and Education (ONE) Network for multimedia educational courses in each subspecialty of ophthalmology.

The ROP tele-education system we have developed can be one of many tools utilized in the Milestones Project to improve and standardize ROP training in the United States and internationally. We believe that it may be worthwhile to provide a tele-education program to ophthalmology residents during the ophthalmology ROP rotation, where they will also have exposure to ROP screening. Coupling our ROP tele-education program with hands-on patient exposure may be synergistic with indirect ophthalmoscopy for teaching proficiency in ROP diagnosis. Providing trainees with a minimum requirement or competency level, as determined by adequate completion of the ROP tele-education program, and establishing ROP knowledge prior to bedside exams may potentially minimize the time needed for the ROP examination by ophthalmologists-in-training and also lessen patient morbidity.

IMPACT ON INTERNATIONAL RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY CARE

Tele-education also offers the unique opportunity to provide high-quality education to medical trainees in developing countries, particularly those with a critical shortage of medical faculty. Until recently, e-learning initiatives in developing countries were hampered by technological limitations, including lack of access to computers and lack of or limited Internet availability. There has been an exponential increase in Internet capacity and a decreasing cost associated with Internet access, both of which can facilitate the implementation of a tele-education model.

One particularly intriguing initiative focuses on the Open Educational Resources (OER) movement, which was initially devised at a 2002 forum on Open Courseware organized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). This movement encourages “teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others. Open educational resources include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and any other tools, materials, or techniques used to support access to knowledge.”93

A common model for ROP educational training has involved experts administering international workshops to educate clinicians to improve ROP diagnosis in middle-income countries. Additionally, international organizations like Orbis International are leading educational initiatives for ROP care.94,95 Although workshops and conferences provide immediate assistance, they lack sustainability without the enormous efforts of the various stakeholders. Furthermore, this educational model is hindered by logistical concerns, including time and travel costs.

With these concerns, a tele-education initiative may be a more contextually appropriate and sustainable solution that can reach a wider audience. The development of widespread retinal imaging of ROP would allow for the creation of digital repositories that could serve as teaching resources for trainees in remote parts of the world. Such repositories could also serve to assess ROP competency and ensure that trainees are receiving adequate ROP education.