Abstract

Background

Synthetic cannabinoids have emerged as a significant public health concern. To increase the knowledge of how these molecules interact on brain reward processes, we investigated the effects of CP55,940, a high efficacy synthetic CB1 receptor agonist, in a frequency-rate intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) procedure.

Methods

The impact of acute and repeated administration (seven days) of CP55,940 on operant responding for electrical brain stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle was investigated in C57BL/6J mice.

Results

CP55,940 attenuated ICSS in a dose-related fashion (ED50 (95% C.L.) = 0.15 (0.12–0.18) mg/kg). This effect was blocked by the CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant. Tolerance developed quickly, though not completely, to the rate-decreasing effects of CP55,940 (0.3 mg/kg). Abrupt discontinuation of drug did not alter baseline responding for up to seven days. Moreover, rimonabant (10 mg/kg) challenge did not alter ICSS responding in mice treated repeatedly with CP55,940.

Conclusions

The finding that CP55,940 reduced ICSS in mice with no evidence of facilitation at any dose is consistent with synthetic cannabinoid effects on ICSS in rats. CP55,940-induced ICSS depression was mediated through a CB1 receptor mechanism. Additionally, tolerance and dependence following repeated CP55,940 administration were dissociable. Thus, CP55,940 does not produce reward-like effects in ICSS under these conditions.

Keywords: synthetic cannabinoid; intracranial self-stimulation; mice; withdrawal; tolerance; dependence; CP55,940

1. INTRODUCTION

Cannabis sativa has been used both medicinally and recreationally for thousands of years (Mechoulam et al., 1991). The psychotropic effects of this plant are due mainly to its primary psychoactive constituent Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (Mechoulam and Gaoni, 1965; Martin-Santos et al., 2012). THC falls within the class of drugs known as cannabinoids, which draw their moniker from the cannabis plant. Cannabinoids are primarily defined by their ability to bind and activate cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) (Herkenham et al., 1990; Matsuda et al., 1990) and cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) (Munro et al., 1993). Although CB1 is well known to play a predominant role in mediating the behavioral effects of THC and other cannabinoids and to modulate the rewarding effects of other classes of drugs (Rinaldi-Carmona et al., 1994; Ledent et al., 1999; Zimmer et al., 1999; Forget et al., 2005), emerging evidence indicates that CB2 plays opposing roles in the reinforcing effects of cocaine and nicotine (Xi et al., 2011; Ignatowska-Jankowska et al., 2013; Navarrete et al., 2013).

In addition to THC, hundreds of synthetic cannabinoids vary in structure and bind and activate cannabinoid receptors (for review, see (Pertwee 2006)). These synthetic compounds were crucial for establishing the binding and distribution of cannabinoid receptors in brain (Devane et al., 1988; Herkenham et al., 1990). However, in recent years, synthetic cannabinoids such as CP-47,497 (Hudson et al., 2010), AM-2201 (Denooz et al., 2013), JWH-018, and JWH-073 (Brents and Prather 2014), emerged as new drugs of abuse. Synthetic cannabinoids are generally abused by smoking plant material imbued with these compounds in much the same manner as marijuana, and are readily available as preparations commonly referred to as “Spice” or “K2” among other brand names (Fantegrossi et al., 2014). Synthetic cannabinoids are often markedly more potent and/or efficacious than THC (Griffin et al., 1998). Moreover, toxicological information is limited, and little is known about how these compounds affect brain reward circuitry in vivo. As synthetic cannabinoids have emerged as drugs of abuse (Maxwell, 2014), further research is needed to characterize their pharmacology and toxicology. The impact of chronic exposure to nonclassical cannabinoids also remains to be determined.

Similar to other drugs of abuse, cannabinoids can evoke dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), a characteristic often indicative of drugs of abuse (Chen et al., 1993; Cheer et al., 2004). The NAc is one node in a neural circuit known as the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, which consists of dopaminergic neurons that originate in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and project to NAc and more rostral targets such as prefrontal cortex (PFC). Intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) of the medial forebrain bundle is one procedure that has been used to measure reinforced behavior mediated by the mesolimbic dopamine pathway (Carlezon and Chartoff, 2007) and to assess abuse potential of drugs (Negus and Miller, 2014). Although acute administration of synthetic cannabinoids generally suppresses ICSS (Arnold et al., 2001; Vlachou et al., 2003, 2005), the impact of repeated cannabinoid administration on ICSS has not been extensively studied but may be important. For example, repeated administration of mu opioid agonists evokes tolerance to their rate-decreasing effects and unmasks abuse-related ICSS facilitation (Altarifi and Negus, 2011; Altarifi et al., 2012). Additionally, ICSS has been used to detect withdrawal-related anhedonia for some drugs of abuse such as cocaine, nicotine and morphine (Altarifi and Negus, 2011; Stoker et al., 2012, 2014).

In the present study we tested the hypotheses that (a) repeated administration of a synthetic cannabinoid will facilitate ICSS in a similar fashion as other abused drugs, and (b) spontaneous or antagonist-precipitated withdrawal in mice repeatedly administered cannabinoids will produce an anhedonia-like depression of ICSS similar to that produced by withdrawal from other abused drugs. Because of the wide variety of synthetic cannabinoids and the ever changing composition of abused preparations, we chose to use a single, representative compound, CP55,940, to model acute and repeated effects of synthetic cannabinoids. Although CP55,940 has not emerged as a drug of abuse and has not been scheduled by the Drug Enforcement Agency, it has been extensively characterized in preclinical studies, and it is structurally similar to the abused and scheduled nonclassical cannabinoids CP47,497 and cannabicyclohexanol (Logan et al., 2012). Moreover, these compounds bind with similar affinity to CB1 and CB2 (Huffman et al., 2010; Atwood et al., 2011). Acute administration of CP55,940 depressed ICSS in rats (Arnold et al., 2001; Kwilasz and Negus, 2012), but its consequences on ICSS following repeated administration are unknown.

In initial experiments, we examined the dose-response relationship and time course of the effects of acute CP55,940 administration on ICSS. Rimonabant was used to infer CB1 involvement. We then tested whether the acute effects of CP55,940 on ICSS would undergo tolerance following repeated administration. Because cannabinoids are well established to alter motor function, such as catalepsy, we also assessed the relationship between catalepsy and ICSS measures during repeated administration of CP55,940 (Little et al., 1988). Catalepsy was selected as a concurrent endpoint because the behavior may confound the ability of the mice to engage in operant responding, and CB1-mediated depression of ICSS may reflect non-specific disruption of behavior rather than an ICSS specific effect. Finally, we examined whether mice treated repeatedly with CP55,940 displayed signs of either spontaneous or precipitated withdrawal in the ICSS procedure.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Subjects

A total of 43 male C57Bl/6J mice were used (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine). Mice were between 10 and 14 weeks of age at the start of each experiment and were individually housed and maintained on a 12 h light cycle, with lights on from 0600 to 1800 h, with free access to food and water. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

2.2 Drugs

CP55,940, rimonabant and cocaine HCl were obtained from the National Institute of Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program (Rockville, MD). CP55,940 and rimonabant were dissolved in a vehicle (VEH) consisting of 5% ethanol, 5% Emulphor-620 (Rhone-Poulenc, Princeton, NJ), and 90% 0.9% saline. Cocaine was dissolved in 0.9% saline.

2.3 Intracranial Self-Stimulation (ICSS)

2.3.1 Apparatus

ICSS testing was conducted in eight mouse operant conditioning chambers (18 × 18 × 18 cm; Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT). Each chamber was equipped with a retractable lever located on one wall, LED stimulus lights over the lever, a chamber house-light, a tone-generator and an ICSS stimulator. The stimulator was connected to the electrode via bipolar cables routed through a swivel commuator and into the experimental chamber. Chambers were enclosed within sound- and light-attenuating chambers equipped with exhaust fans. Custom software was used to control manipulations in the operant chambers and to record data during training and testing sessions.

2.3.2 Stereotaxic Surgery

Surgical procedures for implanting electrodes in mice for ICSS studies were similar to those previously reported (Carlezon and Chartoff, 2007; Wiebelhaus et al., 2014). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane for implantation of bipolar twisted stainless steel electrodes (0.280 mm diameter and insulated except at the flat tips; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) into the right medial forebrain bundle (2.0 mm posterior to bregma, 0.8 mm lateral from midline, and 4.8 mm below dura). The electrode was fixed to the skull with anchoring screws and dental cement. Mice were given acetaminophen (1–2 mg/ml) in their drinking water for one day before and five days after surgery. Training began one week after surgery.

2.3.4 Training

During initial training, lever-press responding under a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule produced both (a) delivery of a 0.5 s train of square-wave cathodal pulses (0.1 ms pulse duration) at a frequency of 141 Hz and amplitude of 150 µA and (b) 0.5 s onset of stimulus lights, house light, and tone cues. Responding during stimulation had no scheduled consequences. Amplitudes of stimulation were individually adjusted for each mouse to maximize response rates, and final amplitudes ranged from 45–300 µA. Training continued during daily 30–120 min sessions until response rates exceeded 30 responses per min for at least three days.

Once operant responding was established, mice were promoted to frequency-rate training as previously reported for mice (Wiebelhaus et al., 2014) and rats (Negus et al., 2010). Frequency-rate sessions were divided into multiple components, and each component consisted of 10 sequential frequency trials for presentation of a descending series of 10 stimulation frequencies (2.2–1.75 log Hz in 0.05 log increments). Each frequency trial began with a 10 sec time out period, during which behavior had no scheduled consequences. During the last 5 s of the time out period, the lever was extended, and non-contingent stimulations were delivered once per second at a given frequency together with associated cues The time out period was followed by a 60 s response period when responding under the FR1 schedule produced brain stimulation at the specified frequency together with associated cues. After the 60 s response period, the lever was retracted, the stimulation frequency was decreased by 0.05 log units, and the next frequency trial began. Sessions consisted of three to five consecutive components per day, and current amplitudes were adjusted if necessary for each subject to maintain responding for at least three, and fewer than eight, stimulation frequencies at levels ≥ 50% maximal control rates (see Data Analysis).

Once these criteria were met, preliminary testing was initiated. Test sessions consisted of three baseline components followed first by a 30 min treatment interval and then by two test components. Data from the first baseline component for each test session were excluded from analysis. Data from the next two baseline components were averaged to generate baseline data for that test session, and data from the test components were averaged to generate test data. Mice were eligible for drug testing when the total number of stimulations per component during baseline varied by less than 20% on three consecutive days, and baseline and test numbers of stimulations per component differed by ≤ 20% in the absence of an injection or after treatment with vehicle injections. Brains were harvested from select mice, which met criteria throughout testing, and histological analysis was performed to verify of electrode placement into the lateral hypothalamus1. Microscopy was performed at the VCU Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology Microscopy Facility, supported, in part, with funding from the NIH-NINDS Center core grant (5P30NS047463).

2.3.5 Dose-Effect Relationship of CP55,940

Once the training criteria were met, drug testing was initiated using dose-effect, time-course and repeated-dosing procedures. For antagonism studies, a single dose of CP55,940 (0.03–1.0 mg/kg, s.c. 30 minutes prior to test components) was administered alone or 15 min after rimonabant2 (3–30 mg/kg). The effects of cocaine (10.0 mg/kg, i.p. 10 min prior to testing) were also tested as a positive control3. Test sessions were separated by at least 72 hr.

2.3.6 Time Course of CP55,940

The procedures described above were modified to assess the onset and duration of effects produced by CP55,940. Test sessions consisted of three baseline components followed first by a 5 min treatment interval and then by pairs of test components beginning 5 min, 30 min, 2 hr, 4 hr and 8 hr after injection. Mice were removed from the test chamber between the last four pairs of test components. If necessary, drug effects were also evaluated after 24 and 48 hr. The time course of vehicle injection was tested first. If the number of stimulations per component varied ≤ 20% for all test components from 5 min to 8 hr, then an identical procedure was used to evaluate effects of 0.3 and 1.0 mg/kg CP55,940. Two different groups of mice were used for each dose in the time course studies. Thus, each group had a corresponding vehicle time course for comparison.

2.3.7 Repeated Administration of CP55,940

To test the effects of a fixed dose of CP55,940 administered repeatedly, two groups of mice were assessed in three phases, each of which lasted for seven days. On each day of Phases 1 and 2, test sessions consisted of three baseline components followed first by treatment interval and then by two test components. Injections were administered during the treatment interval, 30 min before initiation of the test components. In addition, mice were tested for catalepsy (see below) immediately before the injection and again approximately 20 min after completion of the test components (75 min after the injection).

The first phase of testing consisted of seven consecutive days of vehicle testing using the procedure described above. This phase established a baseline for comparison to phases 2 and 3 and permitted assessment of stability of responding during daily vehicle injections. If the number of stimulations per component during baseline components varied ≤ 20%, across days, and if the number of baseline and test stimulations per component varied ≤ 20% on each day, then mice were advanced to subsequent phases. In phase two, the mice were divided into separate groups. One group continued receiving daily injections of vehicle, whereas the second group received daily injections of 0.3 mg/kg CP55,940. In phase 3, treatment with CPP55,940 terminated, and only baseline components were conducted to probe for evidence of spontaneous withdrawal and to investigate whether or not mice would return to pre-drug baselines.

Precipitated withdrawal experiments were conducted in a third group of mice in three phases as described above with the following procedural differences. Four h after the final injection of phase 1, mice were injected with 10 mg/kg rimonabant to examine its effects on ICSS before CP55,940 exposure. After two or three days of subsequent vehicle tests to allow for washout of rimonabant, mice were given daily injections of 0.3 mg/kg CP55,940 (Phase 2). On day 7 of phase 2 mice were given a second test with rimonabant (10 mg/kg, 10 min i.p., 4h after CP55,940) to precipitate withdrawal.

2.3.8 Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. The primary dependent variables were the number of stimulations per min for each frequency and the number of stimulations per component across all frequencies as described previously (Negus and Miller, 2014; Wiebelhaus et al., 2014). These data were then evaluated using two separate approaches. First, data for each frequency trial during baseline and test components were expressed as percent Maximum Control Rate (%MCR), with maximum control rate defined as the maximum average rate observed at any frequency during baseline components for that mouse on that day. %MCR data were averaged across mice to generate the frequency-rate curves that were assessed using repeated-measures two-way ANOVAs (treatment × frequency) between baseline and treatment curves for each drug/dose tested. A significant ANOVA was followed by the Holm-Sidak test, and the criterion for significance was p<0.05.

In the second approach, the average total number of stimulations per test component was divided by the average number of stimulations per baseline component for each mouse on each day, and multiplied by 100, to produce percent baseline stimulations (% baseline stimulations). These data were averaged across mice for each treatment and compared with one-way ANOVAs (Wiebelhaus et al., 2014). A significant ANOVA was followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test to compare treatment groups with VEH controls.

Data from repeated-treatment studies were analyzed using both % MCR and % baseline stimulations measures. For tolerance studies each day in phase 2 was compared within each group to each other day as well as to average data from phase 1. Additionally, % baseline stimulations were also analyzed between groups by day. Selected frequency-rate curves from phase 1 day 7 (i.e. pre-drug), and days 1, 2 and 7 from phase 2 were used to assess both tolerance across days and the acute effect of CP55,940 each day. Precipitated withdrawal studies compared the frequency-rate curves between baselines, CP55,940 tests, and rimonabant tests in phase 1 day 7 and phase 2 day 7.

2.4 Catalepsy

2.4.1 Procedure

Catalepsy was measured during 60 s test periods. At the start of each test period, the forepaws of the mouse were placed on a metal bar raised 4.5 cm from a metal platform. If a mouse removed its forepaws from the bar, the forepaws were replaced up to four times or until the testing period ended, whichever occurred first. The total time the mouse retained its forepaws on the bar was recorded. During the spontaneous and precipitated withdrawal experiments, catalepsy was measured immediately after ICSS baseline and test components. Approximately 75 min lapsed between these measurements during ICSS studies, so the same interval was used in control experiments without ICSS.

2.4.2 Data Analysis

Catalepsy data are expressed as the change from baseline measurements after a 75 min pretreatment and analyzed utilizing two-way ANOVA. To determine whether the expression of catalepsy correlated with rate-decreasing effects of repeated dosing with CP55,940, a Pearson correlation was conducted between the change from baseline in catalepsy versus the % baseline stimulations.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Potency, Time Course and Rimonabant Antagonism of CP55,940 Effects on ICSS

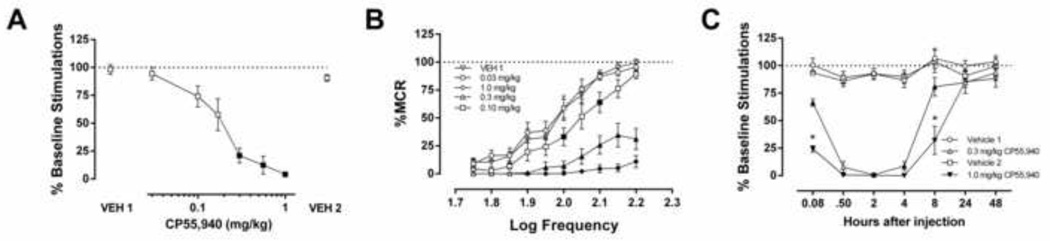

Whereas cocaine (10 mg/kg) facilitated ICSS (Supplemental Figure 14), CP55,940 (30 min pretreatment) produced dose-related reductions in ICSS. The % baseline stimulations measure shows that CP55,940 (0.3–1.0 mg/kg) depressed ICSS with no evidence for facilitation at any dose (Figure 1A, (F (2.640, 18.89) = 40.1) p < 0.001). The ED50 (95% confidence limits) of CP55,940 to produce rate-decreasing effects was 0.15 (0.12–0.18) mg/kg. Similarly, CP55,940 produced dose-dependent rightward and downward shifts in the ICSS frequency-rate curve (Figure 1B, (F (9, 63) = 85.9, p < 0.001). Finally, time-course studies revealed that 0.3 and 1.0 mg/kg CP55,940 decreased ICSS within 5 min, and these rate-decreasing effects persisted for up to 8 h (F (18, 132) = 20.27, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Acute administration of CP55,940 suppressed ICSS through a CB1 receptor mechanism of action. A. (%Baseline stimulations) and B. (%MCR). CP55,940 dose-dependently decreased ICSS. n=8; filled squares indicate p<0.05 vs. VEH 1, C. CP55,940-induced ICSS depression persisted for up to 8 h (n=6–7, filled squares indicate p<0.05 vs. respective vehicle control, *p<0.0001 0.3 mg/kg vs. 1.0 mg/kg CP55,940).

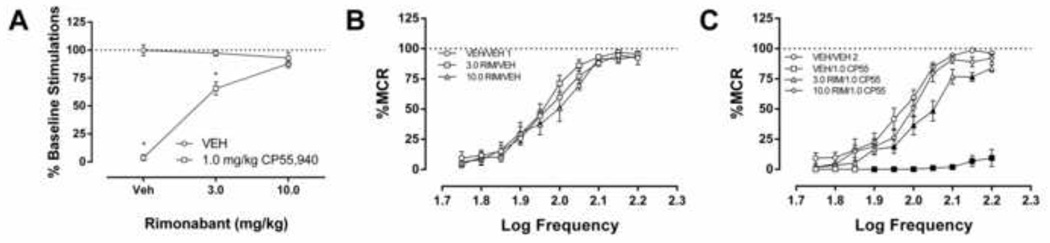

Whereas rimonabant (3.0–30.0 mg/kg) administered alone had no effect on % baseline stimulations (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 25), it dose-dependently prevented the depressive effects of CP55,940 (1.0 mg/kg) on ICSS (Figure 2A: F (2,12) = 104.7, p < 0.001). Analysis of the frequency-rate data indicated no effect of rimonabant alone (Figure 2B: F (18, 108) = 1.131, p = 0.333), and a dose-dependent reversal of CP55,940-induced suppression of ICSS (Fig 2C: F (27, 162) = 18.4, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

A. The CB1 antagonist rimonabant (3.0 or 10.0 mg/kg) did not affect ICSS when administered alone, but blocked the rate-decreasing effects of CP55,940 (n=7, filled squares indicate p<0.05 VEH vs. 1.0 mg/kg CP55,940, *p<0.0001 vs. 10.0 mg/kg rimonabant) B. Frequency-rate analysis of rimonabant alone and vehicle test revealed no significant difference (n=7). C. CP55,940 (1.0 mg/kg) suppressed ICSS, which was prevented by rimonabant (n=7, filled squares indicate p<0.05 vs vehicle 2).

3.2 Effects of Repeated CP55,940

The average % baseline stimulations for each mouse during seven days of vehicle injections was used for comparison to assess effects of phase 2 treatments with vehicle or different CP55,940 doses (seven day averages (±2.14 SEM) for the number of baseline stimulations per component: Group 1: 97.73 (±2.14), Group 2: 102.49 (±1.57), Group 3: 99.11 (±2.52)). Figure 3A shows effects of repeated vehicle or 0.3 mg/kg CP55,940 on % baseline stimulations during phase 2 (F (14, 91) = 3.3, p < 0.001)). Repeated treatment with vehicle during phase 2 did not alter ICSS. However, the first injection of CP55,940 (0.3 mg/kg) significantly reduced ICSS to a similar degree as in the dose-effect study (see Figure 1A). Tolerance to rate-decreasing effects developed by day 3 in both CP55,940-treated groups, and on day 5, both groups of CP55,940-treated mice no longer displayed differences from the vehicle-injected mice. Repeated treatment with vehicle during phase 2 also produced no change in frequency-rate measures of ICSS (Figure 3B; F (27, 108) = 0.74, p = 0.81). The CP55,940-treated groups showed an initial suppression of ICSS on day 1 and partial recovery of ICSS occurred on later days (Figure 3C; F (27, 135) = 3.4, p < 0.0001; Figure 3D; F (27, 135) = 1.784, p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Partial tolerance developed to a fixed dose of CP55,940 (0.3 mg/kg). A. Tolerance developed to the rate-decreasing effects of CP55,940 by day 2 in CP55,940 Group 1 (n=6, $$p<0.01, $$$p<0.001, $$$$p<0.0001 vs. day 1) and by day 3 in CP55,940 Group 3 (n=6, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. day 1, although rates of responding never returned to vehicle levels within either group. B. The response rates for the repeated vehicle group remained ±20% of their phase 1 average, indicating no effect of repeated injections on ICSS (n=5).C, D. Frequency-rate analysis revealed similar pattern of tolerance in mice receiving repeated administration of CP55,940 (CP55,940 Group 2 and 3 (filled squares p<0.05 vs. pre-drug, ****p<0.0001 day 1 vs. day 7).

Repeated treatment with 0.3 mg/kg CP55,940 also increased catalepsy in ICSS mice as well as in a separate group of mice that did not undergo ICSS training and testing. (Supplemental Figure 3A6, F (14, 105) = 2.693, p < 0.01). Catalepsy was assessed after baseline ICSS and after CP55,940 administration to assess the role of this motor behavior. The cataleptic effects of CP55,940 were greatest on day 1 of treatment and reduced by day 2, but significant catalepsy persisted throughout the seven days of repeated administration. There was no correlation between the degree of catalepsy and the degree of ICSS suppression (Supplemental Figure 3B7; r = 0.07, p=0.69).

Termination of vehicle or CP55,940 treatment did not alter ICSS during the subsequent seven days (Figure 4A; interaction day vs group F (40, 280) = 0.8, p = 0.74). In addition, administration of 10 mg/kg rimonabant did not depress ICSS when it was administered before or after repeated treatment with CP55,940. Figure 4B shows that rimonabant did not alter ICSS as measured by % baseline stimulations in this group of mice (F (18, 90) = 0.80, p = 0.69). Figure 4C shows the effects of 10 mg/kg rimonabant on full frequency-rate curves before CP55,940 treatment (F (18,90) = 0.80, p = 0.69). The final dose of 0.3 mg/kg CP55,940 produced acute suppression of ICSS relative to the pre-drug baseline, and rimonabant blocked this suppression (Figure 4D, F (18, 90) = 2.0, p< 0.05).

Figure 4.

There was no evidence of spontaneous or precipitated withdrawal following 7 days of once daily injections of 0.3 mg/kg CP55,940. A. Basal ICSS responses for each phase of testing (tests were performed prior to injections of vehicle or drug).Throughout the 21 days of testing, each group did not deviate ±20% on during basal testing. B. Rimonabant (10.0 mg/kg, i.p.) did not affect ICSS in mice treated repeated with either vehicle or CP55,940 (n=6) C. Frequency-rate curves on the same days revealed no effect of rimonabant after 7 days of vehicle on phase 1 day 7 (n=6). D. CP55,940 (0.3 mg/kg) administered on seven consecutive days suppressed ICSS. Rimonabant (10.0 mg/kg) 4 hours after the final CP55,940 injection returned responding to baseline levels, consistent with pharmacological blockade of CB1 (n=6, filled square indicate p<0.05 vs baseline).

4. DISCUSSION

Acute administration of CP55,940 dose-dependently and time-dependently depressed ICSS in mice. The observation that rimonabant prevented the rate-decreasing effects of CP55,940 indicates that these effects were CB1 receptor mediated. The fact that rimonabant given alone did not alter ICSS indicates that CB1 receptors play a negligible role in basal responding in this ICSS procedure. Partial tolerance developed after repeated exposure to a fixed dose of CP55,940, but there was no evidence to suggest that this tolerance to rate-decreasing effects of CP55,940 unmasked expression of abuse-related rate-increasing effects. Moreover, neither spontaneous nor rimonabant-precipitated withdrawal altered ICSS in mice treated repeatedly with 0.3 mg/kg CP55,940, suggesting that this regimen of CP55,940 treatment was not sufficient to produce dependence. Finally, catalepsy did not correlate with reduced ICSS after exposure to CP55,940. Taken together, these results indicate that CP55,940 did not produce reward-like effects in ICSS after either acute or repeated administration.

4.1 Acute effects of CP55,940 in ICSS

Acute administration of CP55,940 suppressed ICSS in mice with a potency approximately 57 (35–95)-fold greater than that of THC (Wiebelhaus et al., 2014). The observed difference in potency is consistent with the affinities of THC and CP55,940 for CB1. Reported in vitro Ki values for THC are approximately 40 nM, whereas CP55,940 Ki is approximately 0.9 nM, reflecting a difference in affinity of 45 fold for the CB1 receptor (Compton et al., 1993). Potencies between THC and CP55,940 in vivo range from 4- to 15-fold in catalepsy, tail withdrawal, and rectal temperature assays (i.v. route of administration) in male ICR mice (Compton et al., 1992) and up to 82-fold in a drug discrimination procedure (i.p. route of administration) in male C57BL6/J mice (McMahon et al., 2008). Previous studies examining the acute effects of CP55,940 found that a dose range of 0.01–0.05 mg/kg did not affect ICSS, but doses of 0.1 mg/kg and higher depressed ICSS in rats (Arnold et al., 2001; Mavrikaki et al., 2010; Kwilasz and Negus, 2012). The present study represents the first publication reporting the effects of CP55,940 on ICSS in mice, and we found that a similar dose range reduced ICSS in this species. Importantly, there was no evidence for ICSS facilitation at low CP55,940 doses that did not suppress ICSS in mice, consistent with previous studies investigating synthetic cannabinoids in rat ICSS (Arnold et al., 2001; Mavrikaki et al., 2010; Kwilasz and Negus, 2012). Although facilitation of ICSS by THC has been reported previously in rats (Gardner et al., 1988; Katsidoni et al., 2013), it should be noted that facilitation generally occurs at low doses in select strains of rats (Lewis and Sprague-Dawley) in a subset of published studies, and the magnitude of facilitation is relatively small compared to that produced by psychomotor stimulants such as cocaine (for review, see Negus and Miller, 2014). Furthermore, THC attenuates ICSS in mice. Given the failure of CP55,940 to produce evidence of ICSS facilitation even at doses as low 0.03 mg/kg, the results of the present extend the range of conditions under which cannabinoids fail to facilitate ICSS in rodents.

Whereas rimonabant completely prevented CP55,940-induced depression of ICSS, this drug given alone did not alter ICSS. Previous studies in rats and mice also found that ICSS was not altered by CB1 receptor antagonist doses sufficient to block effects of exogenous cannabinoids (Vlachou et al., 2005, 2006; Kwilasz and Negus, 2012; Katsidoni et al., 2013). These findings suggest that endocannabinoids acting at CB1 receptors do not tonically modulate neural substrates that mediate ICSS.

4.2 Tolerance to the rate-decreasing effects of CP55,940

In the present study, the depressive effects of 0.3 mg/kg CP55,940 on ICSS underwent tolerance by the second day of treatment. While this tolerance persisted for the remaining seven days of drug administration, tolerance was not complete, as CP55,940 continued to attenuate ICSS. For comparison, complete tolerance developed to THC-induced depression of ICSS in rats treated for 22 days with an escalating regimen of THC doses (Kwilasz and Negus, 2012), but no tolerance developed to depression of ICSS by repeated treatment with the synthetic cannabinoid WIN55,212-2 (Mavrikaki et al., 2010). Although assessment of rightward shifts in the dose response relationship to quantify the magnitude of tolerance were not conducted, these apparent discrepancies in tolerance development to a single dose of drug may be related to the rank order of efficacies of these cannabinoids at CB1 receptors (WIN55,212-2>CP55,940>THC) (Breivogel et al., 1998). Similarly, the extent of antinociceptive tolerance to mu opioid agonists was found to be inversely related to efficacy of the agonists at mu receptors (Yaksh 1992; Duttaroy and Yoburn, 1995). More generally, it appears that low- vs. high-efficacy ligands occupy higher proportions of receptors to produce equivalent acute effects, down-regulate a higher proportion of receptors during chronic treatment, and are more sensitive to reductions in the density of functional receptors produced by that downregulation.

The findings in the present study indicate little evidence for abuse potential and dependence for CP55,940. Tolerance developed quickly but incompletely to the rate-decreasing effects of CP55,940 on ICSS. The bulk of studies investigating the effects of synthetic cannabinoids on ICSS examined acute drug administration, and only one study of which we are aware examined repeated administration of a synthetic cannabinoid in rats (Mavrikaki et al., 2010). Thus, the present body of work represents the first study to examine tolerance and dependence of a synthetic cannabinoid in a mouse ICSS procedure. Although there was no evidence for spontaneous or rimonabant-precipitated withdrawal, the depressive effects of CP55,940 on ICSS showed partial tolerance following repeated administration. It is reasonable to suspect these findings could be extended to other bicyclic cannabinoids which have a history of abuse such as CP47,497 (Papanti et al., 2013; Koller et al., 2014). Overall, these experiments reveal the greatly increased potency of synthetic cannabinoids and their potentially detrimental effects on brain reward following acute or repeated administration.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

CP55,940 dose-dependently suppressed ICSS in C57BL6/J mice through a CB1 mechanism of action, but no evidence for facilitation at any dose.

Repeated dosing with CP55,940 resulted in partial tolerance to its rate-decreasing effects.

Mice treated repeatedly CP55,940 show no evidence of spontaneous or precipitated withdrawal on ICSS.

Little support for abuse potential of CP55,940 based on ICSS data.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health grants [T32DA007027, R01DA032933, RO1DA030404, and 1F31DA030689]. The funding source had no involvement in the research reported in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Author Disclosures

Authorship and contributions

Travis W. Grim performed the majority of the surgeries, data collection, data analysis, assisted with histological verification of electrode placement, contributed to experimental design, and composition of the manuscript.

Jason M. Wiebelhaus performed some surgeries, lent technical expertise on the intracranial self-stimulation procedure, and contributed to experimental design.

Anthony Morales performed the majority of tasks related to histological verification of electrode placement.

S. Stevens Negus provided technical expertise concerning intracranial self-stimulation procedure, data analysis, experimental design, conceptual input, and contributed to the composition of the manuscript.

Aron H. Lichtman provided input on design and analysis of behavioral experiments, selection and utilization of pharmacological tools, and composition of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

No authors report conflicts of interest which could have influenced, or perceived to have influenced, this work.

REFERENCES

- Altarifi AA, Miller LL, Negus SS. Role of micro-opioid receptor reserve and micro-agonist efficacy as determinants of the effects of micro-agonists on intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Behav. Pharmacol. 2012;23:678–692. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328358593c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altarifi AA, Negus SS. Some determinants of morphine effects on intracranial self-stimulation in rats: dose, pretreatment time, repeated treatment, and rate dependence. Behav. Pharmacol. 2011;22:663–673. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32834aff54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JC, Hunt GE, McGregor IS. Effects of the cannabinoid receptor agonist CP 55,940 and the cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR 141716 on intracranial self-stimulation in Lewis rats. Life Sci. 2001;70:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood BK, Lee D, Straiker A, Widlanski TS, Mackie K. CP47,497-C8 and JWH073, commonly found in 'Spice' herbal blends, are potent and efficacious CB(1) cannabinoid receptor agonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;659:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Selley DE, Childers SR. Cannabinoid receptor agonist efficacy for stimulating [35S]GTPgammaS binding to rat cerebellar membranes correlates with agonist-induced decreases in GDP affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16865–16873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brents LK, Prather PL. The K2/Spice phenomenon: emergence, identification, legislation and metabolic characterization of synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense products. Drug Metab. Rev. 2014;46:72–85. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2013.839700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Chartoff EH. Intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) in rodents to study the neurobiology of motivation. Nature Protoc. 2007;2:2987–2995. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheer JF, Wassum KM, Heien ML, Phillips PE, Wightman RM. Cannabinoids enhance subsecond dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of awake rats. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4393–4400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0529-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Marmur R, Pulles A, Paredes W, Gardner EL. Ventral tegmental microinjection of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol enhances ventral tegmental somatodendritic dopamine levels but not forebrain dopamine levels: evidence for local neural action by marijuana's psychoactive ingredient. Brain Res. 1993;621:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton DR, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Martin BR. Pharmacological profile of a series of bicyclic cannabinoid analogs: classification as cannabimimetic agents. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;260:201–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton DR, Rice KC, De Costa BR, Razdan RK, Melvin LS, Johnson MR, Martin BR. Cannabinoid structure-activity relationships: correlation of receptor binding and in vivo activities. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;265:218–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denooz R, Vanheugen JC, Frederich M, de Tullio P, Charlier C. Identification and structural elucidation of four cannabimimetic compounds (RCS-4, AM-2201, JWH-203 and JWH-210) in seized products. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2013;37:56–63. doi: 10.1093/jat/bks095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devane WA, Dysarz FA, 3rd, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Howlett AC. Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol. Pharmacol. 1988;34:605–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duttaroy A, Yoburn BC. The effect of intrinsic efficacy on opioid tolerance. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:1226–1236. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199505000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Moran JH, Radominska-Pandya A, Prather PL. Distinct pharmacology and metabolism of K2 synthetic cannabinoids compared to Delta(9)-THC: mechanism underlying greater toxicity? Life Sci. 2014;97:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget B, Hamon M, Thiebot MH. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are involved in motivational effects of nicotine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2005;181:722–734. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EL, Paredes W, Smith D, Donner A, Milling C, Cohen D, Morrison D. Facilitation of brain stimulation reward by delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1988;96:142–144. doi: 10.1007/BF02431546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin G, Atkinson PJ, Showalter VM, Martin BR, Abood ME. Evaluation of cannabinoid receptor agonists and antagonists using the guanosine-5'-O-(3-[35S]thio)-triphosphate binding assay in rat cerebellar membranes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;285:553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Little MD, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson S, Ramsey J, King L, Timbers S, Maynard S, Dargan PI, Wood DM. Use of high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry to detect reported and previously unreported cannabinomimetics in "herbal high" products. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2010;34:252–260. doi: 10.1093/jat/34.5.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JW, Hepburn SA, Reggio PH, Hurst DP, Wiley JL, Martin BR. Synthesis and pharmacology of 1-methoxy analogs of CP-47,497. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:5475–5482. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatowska-Jankowska BM, Muldoon PP, Lichtman AH, Damaj MI. The cannabinoid CB2 receptor is necessary for nicotine-conditioned place preference, but not other behavioral effects of nicotine in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2013;229:591–601. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3117-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsidoni V, Kastellakis A, Panagis G. Biphasic effects of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on brain stimulation reward and motor activity. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:2273–2284. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713000709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller VJ, Auwarter V, Grummt T, Moosmann B, Misik M, Knasmuller S. Investigation of the in vitro toxicological properties of the synthetic cannabimimetic drug CP-47,497-C8. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014;277:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwilasz AJ, Negus SS. Dissociable effects of the cannabinoid receptor agonists Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and CP55940 on pain-stimulated versus pain-depressed behavior in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012;343:389–400. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.197780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledent C, Valverde O, Cossu G, Petitet F, Aubert JF, Beslot F, Bohme GA, Imperato A, Pedrazzini T, Roques BP, Vassart G, Fratta W, Parmentier M. Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1 receptor knockout mice. Science. 1999;283:401–404. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little PJ, Compton DR, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Martin BR. Pharmacology and stereoselectivity of structurally novel cannabinoids in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;247:1046–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan BK, Reinhold LE, Xu A, Diamond FX. Identification of synthetic cannabinoids in herbal incense blends in the United States. J. Forensic Sci. 2012;57:1168–1180. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Santos R, Crippa JA, Batalla A, Bhattacharyya S, Atakan Z, Borgwardt S, Allen P, Seal M, Langohr K, Farre M, Zuardi AW, McGuire PK. Acute effects of a single, oral dose of d9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) administration in healthy volunteers. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012;18:4966–4979. doi: 10.2174/138161212802884780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavrikaki M, Markaki E, Nomikos GG, Panagis G. Chronic WIN55,212-2 elicits sustained and conditioned increases in intracranial self-stimulation thresholds in the rat. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;209:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JC. Psychoactive substances-Some new, some old: a scan of the situation in the U.S. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon LR, Ginsburg BC, Lamb RJ. Cannabinoid agonists differentially substitute for the discriminative stimulus effects of Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2008;198:487–495. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0900-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R, Devane WA, Breuer A, Zahalka J. A random walk through a cannabis field. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991;40:461–464. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R, Gaoni Y. A total synthesis of dl-delta-1-tetrahydrocannabinol, the active constituent of hashish. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:3273–3275. doi: 10.1021/ja01092a065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete F, Rodriguez-Arias M, Martin-Garcia E, Navarro D, Garcia-Gutierrez MS, Aguilar MA, Aracil-Fernandez A, Berbel P, Minarro J, Maldonado R, Manzanares J. Role of CB2 cannabinoid receptors in the rewarding, reinforcing, and physical effects of nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:2515–2524. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Miller LL. Intracranial self-stimulation to evaluate abuse potential of drugs. Pharmacol Rev. 2014;66:869–917. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Morrissey EM, Rosenberg M, Cheng K, Rice KC. Effects of kappa opioids in an assay of pain-depressed intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:149–159. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1770-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanti D, Schifano F, Botteon G, Bertossi F, Mannix J, Vidoni D, Impagnatiello M, Pascolo-Fabrici E, Bonavigo T. Spiceophrenia: a systematic overview of "spice"-related psychopathological issues and a case report. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2013;28:379–389. doi: 10.1002/hup.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. The pharmacology of cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: an overview. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2006;(30) Suppl. 1:S13–S18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi-Carmona M, Barth F, Heaulme M, Shire D, Calandra B, Congy C, Martinez S, Maruani J, Neliat G, Caput D. SR141716A, a potent and selective antagonist of the brain cannabinoid receptor. FEBS Lett. 1994;350:240–244. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00773-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoker AK, Marks MJ, Markou A. Null mutation of the beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit attenuates nicotine withdrawal-induced anhedonia in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.05.062. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoker AK, Olivier B, Markou A. Involvement of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in brain reward deficits associated with cocaine and nicotine withdrawal and somatic signs of nicotine withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2012;221:317–327. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2578-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou S, Nomikos GG, Panagis G. WIN 55,212-2 decreases the reinforcing actions of cocaine through CB1 cannabinoid receptor stimulation. Behav. Brain Res. 2003;141:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou S, Nomikos GG, Panagis G. CB1 cannabinoid receptor agonists increase intracranial self-stimulation thresholds in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2005;179:498–508. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou S, Nomikos GG, Panagis G. Effects of endocannabinoid neurotransmission modulators on brain stimulation reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2006;188:293–305. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebelhaus JM, Grim TW, Owens RA, Lazenka MF, Sim-Selley LJ, Abdullah RA, Niphakis MJ, Vann RE, Cravatt BF, Wiley JL, Negus SS, Lichtman AH. Delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and endocannabinoid degradative enzyme inhibitors attenuate intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2014 doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.218677. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Peng XQ, Li X, Song R, Zhang HY, Liu QR, Yang HJ, Bi GH, Li J, Gardner EL. Brain cannabinoid CB(2) receptors modulate cocaine's actions in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:1160–1166. doi: 10.1038/nn.2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL. The spinal pharmacology of acutely and chronically administered opioids. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7:356–361. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(92)90089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer A, Zimmer AM, Hohmann AG, Herkenham M, Bonner TI. Increased mortality, hypoactivity, and hypoalgesia in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:5780–5785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.