Abstract

Objective

To present a method of estimating and equating scales across functional assessment instruments that appropriately represent changes in a patient’s functional ability and can be meaningfully mapped to changes in Medicare G-code severity modifiers.

Design

Previously published measures of patients’ overall visual ability, estimated from low vision patient responses to seven different visual function rating scale questionnaires, are equated and mapped onto Medicare G-code severity modifiers

Setting

Outpatient low vision rehabilitation clinics.

Participants

The analyses presented in this paper were performed on raw or summarized low vision patient ratings of visual function questionnaire (VFQ) items obtained from previously published research studies.

Interventions

Previously published visual ability measures from Rasch analysis of low vision patent ratings of items in different visual function questionnaires (NEI VFQ, VF-14, ADVS, and VAQ) were equated with the Activity Inventory (AI) scale –the 39 items in the SRAFVP and the 48 items in the VA LV VFQ were paired with similar items in the AI in order to equate the scales.

Main Outcome Measure

Tests using different observation methods and indicators cannot be directly compared on the same scale. All test results would have to be transformed to measures of the same functional ability variable on a common scale as described here, before a single measure could be estimated from the multiple measures.

Results

Bivariate regression analysis was performed to linearly transform the SRAFVP and VA LV VFQ item measures to the AI item measure scale. The nonlinear relationship between person measures of visual ability on a logit scale and item response raw scores was approximated with a logistic function, and the two regression coefficients were estimated for each of the seven VFQs. These coefficients can be used with the logistic function to estimate functional ability on the same interval scale for each VFQ and for transforming raw VFQ responses to Medicare’s G-code severity modifier categories.

Conclusions

The principle of using equated interval scales allows for comparison across measurement instruments of low vision functional status and outcomes, but can be applied to any area of rehabilitation.

Keywords: G-codes, Low Vision Rehabilitation, Occupational Therapy, Outcome Measures

In the case of chronic vision impairment where recovery of vision is not possible, increasing functional ability and independence is achieved through low vision rehabilitation (LVR): training in the use of visual assistive equipment, sensory substitution strategies, education and counseling.1

In 2002, Medicare mandated coverage of physician-prescribed rehabilitation services for blind and visually impaired beneficiaries.2 To be eligible for LVR service coverage, the disorder must be the result of either a primary eye disease (e.g., macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa, glaucoma), or a condition secondary to another diagnosis (e.g., diabetes, stroke). According to the Medicare Memorandum mandating coverage, rehabilitative therapy for vision impairment by an occupational or physical therapist is designed “to improve functioning…to improve performance of activities of daily living, including self-care and home management skills.”2 Therapeutic services are limited to patients who require reasonable and medically necessary skilled care and who have clearly defined goals.

Beginning July 1, 2013, occupational therapists, physical therapists and speech and language pathologists filing claims for outpatient services under Medicare Part B are required to report the patient’s functional status in the form of “G-codes” to identify the primary issue being addressed by therapy and the patient’s level of impairment/limitation/restriction.3 The G-Codes and severity modifiers must be submitted at the onset of the therapy episode of care with the projected goal status at specified points during treatment and at the time of discharge. In addition to providing the impairment and severity level on the claim, the therapist must track and document the G-codes and modifiers in the patient’s medical record along with the method used to select the modifier (e.g., functional assessment tool used, clinical judgment, etc.). G-codes are divided into 14 categories and are selected and assigned to the encounter by the therapist depending on the type of therapy, goals of therapy and time point in treatment.3 To accompany the G-code, the clinician furnishing the therapy services determines the severity of the limitation and assigns a corresponding modifier as displayed in Table 1. Although the percentage of functional impairment can range from 0% to 100%, the modifier selected must be from 1 of 7 ranked categories.

Table 1.

G-code severity modifier, corresponding percentage of functional impairment/limitation/restriction and range of visual ability measure.

| G-code Modifier | Impairment/Limitation/Restriction | Range of Visual Ability Measure (logits) |

|---|---|---|

| CH | 0% | >3.75 |

| CI | 1–19% | ≤3.75 and >2.65 |

| CJ | 20–39% | ≤2.65 and >1.55 |

| CK | 40–59% | ≤1.55 and >0.45 |

| CL | 60–79% | ≤0.45 and >−0.65 |

| CM | 80–99% | ≤−0.65 and >−1.75 |

| CN | 100% | ≤−1.75 |

Medicare does not currently provide specific guidelines or a list of Medicare-approved functional assessment tools for determining severity modifiers for G-codes. Professional societies and innovative service providers have tried to assist therapists with the new reporting requirement by offering tools to guide selection of appropriate G-code modifiers. An approach used frequently is simple conversion of the raw score of a self-report questionnaire, therapist ratings, or performance test into 1 of 7 severity levels (CH-CN). Tools suggested by the American Occupational Therapy Association are accessible on the Mediware website4, which provides an online calculator that converts the raw score for each of 94 different questionnaires to a G-code severity modifier. The algorithm employed is 100% × (patient’s raw score − minimum raw score)/(maximum raw score − minimum raw score).

Current methods of scaling impairment severity as demonstrated on the Mediware online calculator suggest dividing the raw score range of the test equally from 0 to 100%, using the highest and lowest ordinal test scores to create the boundaries. However, this approach is problematic because it presumes that the average of ordinal response scores for different questionnaires are equivalent and skipping items does not affect the validity of the measure. An alternate approach would be to use ordinal ratings of patient responses, to estimate interval scales that have a ceiling and floor, for each instrument from patient responses to calibrated items. These estimates would then determine boundaries of the scale and equal intervals on which to map G-code severity modifiers.

Currently, the Self-Report Assessment of Functional Visual Performance5 (SRAFVP) is the only LVR outcome measure included in the Mediware G-code severity modifier online calculator. During administration of the SRAFVP, respondents are permitted to skip items that are not applicable; however, the online calculator is fixed and presumes the patient responds to all 39-items. Some calculators allow for missing item responses by adjusting the maximum raw score according to each patient’s response pattern. The calculation of the severity modifier for the SRAFVP is based on the raw score conversion using the standard algorithm on the Mediware site.

To better understand the cost-effectiveness of covered rehabilitation services, G-codes and severity modifiers will be Medicare’s primary data source for analyzing claims. However, Medicare’s lack of guidelines on which functional assessment tools to use and how to transform the observations to standard measures that can be represented by G-code severity modifiers invite chaos in their database and potential misrepresentation of the outcomes of therapy. The present paper addresses the problem of how to map measures of patients’ overall functional ability, not just questionnaire summary scores, onto G-code severity modifiers by estimating functional ability measures on equated interval scales from patient self-reports. The purpose of this paper is to describe a method of estimating and equating interval functional ability scales across instruments that accurately represent the patient’s functional status and can be mapped in a meaningful way to G-code severity modifiers. Although focused on LVR, the approach we describe here can be applied to all types of rehabilitation6.

METHODS

Study Population and Methods

The analyses presented in this paper were performed on raw or summarized patient ratings of visual function questionnaire (VFQ) items obtained from previously published research studies. All studies were approved by appropriate institutional review boards and obtained informed consent from their participants. The present study is a secondary analysis of previously published data. Here we briefly describe the study populations and methods that were used to collect and summarize those data.

Patient responses to the SRAFVP were collected during a 6-month period in 1995 on 102 patients from two low-vision programs5. The SRAFVP sample consisted of primarily older, female individuals, with the majority having macular disease. The SRAFVP is a VFQ with 39 items from different task domains including reading, writing, personal care, meal preparation, mobility and others. Therapists administering the SRAFVP record responses on a five-point rank scale: 1, unable; 2, great difficulty; 3, moderate difficulty; 4, minimal difficulty; and 5, independent (or the patient could respond “not applicable”, which was scored as missing data). The raw scores and the interval-scaled item and person measures estimated from Rasch analysis were provided to us by the authors of the Velozo et al paper.5

Patient responses to the Veterans Affairs Low Vision Visual Functioning Questionnaire (VA LV VFQ) in the Low Vision Intervention Trial7 (n=126, 98% of whom were white and male) were collected from 2004 to 2006. The VA LV VFQ is a 48-item VFQ comprised of items from functional domains including mobility, visual information processing, visual motor skills and overall visual ability. Prior to rehabilitation, participants rated the difficulty of each item using the ordered response categories: (1) not difficult, (2) slightly/moderately difficult, (3) extremely difficult, and (4) impossible. The raw scores and the item and person measures estimated from Rasch analysis were provided by the authors of the LOVIT paper.8

The Activity Inventory (AI) is an adaptive rating scale instrument that has an item bank of 510 calibrated items.9,10 Fifty of the items are general descriptions of activity goals (e.g., prepare a meal, manage personal finances) and nested under the goals are the other 460 items, which are descriptions of specific cognitive and motor activities that are the tasks that must be performed to achieve the parent goal (e.g., measure ingredients, chop food, read bank statement, sign name). Patients are asked to rate the importance of each goal, and if the goal is at least slightly important to the patient, the patient then rates the level of difficulty (not difficult, slightly difficult, moderately difficult, very difficult, or impossible). If the goal is at least slightly difficult, the patient rates the difficulty of the subsidiary tasks necessary to achieve the goal using the same difficulty categories. The adaptive nature of the AI results in using only those items that are important and difficult to the patient, and therefore likely to be incorporated in the rehabilitation goals of the plan of care.11,12 As part of the Low Vision Rehabilitation Outcome Study (LVROS)13 AI responses were obtained from 779 low vision patients enrolled by 28 different clinical centers throughout the U.S. from 2008 to 2011. These data were combined with a legacy data set14 consisting of the AI responses of 2398 low vision patients collected in a prospective study at the Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute from 2001 to 2007. Item measures for all 510 items in the AI item bank were estimated from Rasch analysis of the combined LVROS and legacy databases of patient responses.

From the perspective of Rasch analysis, items used by different VFQs can be considered subsets of a single large item bank that includes the 510 items in the AI.15 If item measures in the item bank are estimated from overlapping samples of patients, then the person measures estimated from responses by the same patients to different VFQs can be equated, thereby equating the scales. Massof et al. (2007) used this method to equate the scales of the National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire (NEI VFQ-25), the Activities of Daily Vision Scale (ADVS), the Visual Activities Questionnaire (VAQ), and the Index of Visual Functioning (VF-14) to the AI scale. The data from that study also are used in the present study.

To similarly equate the SRAFVP scale with the AI scale, the 39 items in the SRAFVP were paired with similar items in the AI (e.g., read TV guide vs. read TV listings). Bivariate linear regression analysis, which minimizes the orthogonal distance to the regression line (i.e., principal component), was performed to linearly transform the SRAFVP item measures to the AI item measure scale. The same analysis was used to equate the VA LV VFQ and AI scales.

The nonlinear relationship between person measures of visual ability on a logit scale and item response raw scores can be approximated with a logistic function, A=b0+b1*ln[(observed raw score − minimum raw score)/(maximum raw score − observed raw score)],13 where A is “ability” and the two coefficients, b0 and b1, are estimated from regression analysis. In a previous study9 coefficients for person measures equated to the AI scale were estimated for the NEI VFQ, ADVS, VAQ, and VF-14. Similarly, in the present study we estimated logistic regression coefficients (b0 and b1) for the AI from the combined LVROS and legacy data sets, as well as for the SRAFVP and the VA LV VFQ from the raw scores and AI-equated person measures using orthogonal least-squares regression.

RESULTS

Figure 1 illustrates the results of our approach to equating the SRAFVP and VA LV VFQ item and person measures with the AI item and person measure scale. The figure shows item measure scatter plots with bivariate regression lines for a) SRAFVP vs. AI and b) VA LV VFQ vs. AI. The r2 values for the regression lines are 0.936 for the SRAFVP and 0.933 for the VA LV VFQ. The regression lines define the transformation of the item and person measure scales for the SRAFVP and the VA LV VFQ required to equate them with the AI item and person measure scale (open circles represent orthogonal projections of the filled data points to the regression line).

Figure 1.

Item measure scatter plots with orthogonal regression lines for a) SRAFVP vs. AI and b) VA LV VFQ vs. AI. The r2 values for the regression lines are 0.936 for the SRAFVP and 0.933 for the VA LV VFQ.

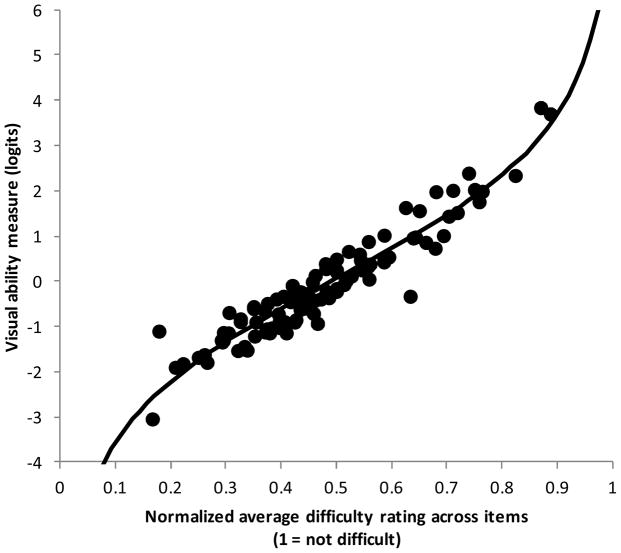

Logistic regression coefficients for transforming the raw scores to person measures of visual ability on a scale equated to the AI scale were estimated for each VFQ. These estimated coefficients for each VFQ, including the AI, are listed in Table 2. Raw scores are defined as the sum of the ordinal difficulty ratings across items. Different instruments use different numbers of response categories and have different numbers of items. Therefore, to compare different VFQs, the most difficult response category in each VFQ was assigned a rank score of 0 and the least difficult response category was assigned the highest rank score. The rank scores were then summed across items to produce a raw score and the raw score was normalized to a 0 to 1 scale (i.e., raw score is divided by the product of the number of items and the rank of the least difficult response category). Figure 2 illustrates the transformation of relative SRAFVP raw scores to visual ability person measures on a scale equated with the AI scale.

Table 2.

Estimated logistic regression coefficients for each questionnaire

| Questionnaire | b0 | b1 |

|---|---|---|

| AI | −0.058 | 1.097 |

| VF 14 | −0.1123 | 0.9859 |

| VAQ | −0.005 | 0.6326 |

| ADVS | −0.01 | 0.7336 |

| NEI VFQ | −0.01 | 0.739 |

| SRAFVP | −0.693 | 0.89074 |

| VA LV VFQ | −0.125 | 0.9243 |

Figure 2.

Mapping of relative SRAFVP raw scores to the equated visual ability scale (solid line) and paired relative raw score/functional ability measures for 102 visually impaired patients (points). The departures from the curve reflect different patients responding to different subsets of the 38 items in the SRAFVP, which effectively changes the shape of the mapping function across patients.

Figure 3 illustrates the mapping of relative raw scores of the 7 different VFQs to the equated visual ability scale using the logistic regression coefficients in Table 2. The previously suggested scaling of the G-code severity modifiers by dividing the relative raw scores into equal intervals are illustrated with the vertical dashed lines (extreme modifiers, CN and CH, are assigned to the extreme relative raw scores). It can be seen that for different VFQs, the same relative raw scores can translate to widely variable visual ability measures (horizontal arrows).

Figure 3.

Illustration of empirical relationships between visual ability and the relative raw scores (i.e., raw score rescaled to range from minimum = 0 to maximum = 1) with an equated visual ability scale on the ordinate for the 7 different visual function rating scales. Shallow slopes indicate a small range of functional ability measures for those instruments and steep slopes indicate a large range of functional ability measures. The arrows indicate the visual ability measure corresponding to a normalized raw score of 0.2 for each of the 7 instruments.

This paper recommends division of the visual ability axis into equal intervals that map onto ordered G-code severity modifiers as shown in Figure 4 for the 3177 low vision patients who responded to the AI. The scatter in the points relative to the curve reflect the different subsets of items used to estimate the visual ability measures across respondents due to the adaptive nature of the AI. A “ceiling” and “floor” for the low vision patient population are created 2 standard deviations from the mean. This calculation makes use of the entire scale, assigning the top 2.5% of patients to the highest functional category and assigning the bottom 2.5% of patients to the lowest functional category. The remaining 95% of the low vision person measure distribution is then divided equally into 19% intervals, which represent the remaining 5 categories of G-code severity modifiers.

Figure 4.

Visual ability measure/normalized raw score pairs estimated from AI responses of 3177 (combined LVROS and legacy data sets) visually impaired patients (points) along with the average mapping function for the sample. The G-code severity modifier categories represent divisions of the visual ability axis rather than raw scores. A “ceiling” and “floor” for the data set are created 2 standard deviations from the mean.

As illustrated in Figure 5, our definition of G-code severity modifiers can be applied to any VFQ score or other indicator variable that has been transformed to an interval visual ability scale equated with the AI visual ability scale.

Figure 5.

The definition of G-code severity modifiers can be applied to any VFQ score or other indicator variable that has been transformed to an interval visual ability scale equated with the AI visual ability scale.

DISCUSSION

The ultimate purpose of utilizing G-code severity modifier categories is to report the magnitude of changes in function as a result of therapy. Patients in the highest functional ability category have the least room for improvement, as they are able to perform some tasks without difficulty and therefore require little need for intervention. The lowest functional ability category represents patients with very poor ability to function. At this level, the patient is severely impaired and may be highly dependent on others to assist with activities. Severity modifiers are assigned at pre-rehabilitation with the aim of improving the patient’s ability to perform specific daily activities important to the patient, which would be represented by an improvement in the category recorded on the G-code severity scale. Without application of scaling with a ceiling and floor, the categories would be larger and the effect size of rehabilitation would be minimized. The larger the G-code modifier category, the more difficult it is to demonstrate a meaningful change in functional ability with change in G-code severity category. This paper recommends estimating functional ability on an interval scale and dividing the functional ability axis into ordered G-code severity modifier categories, rather than assignment of categories to ranges of relative raw scores.

Ideally, all questionnaires, clinical judgments, and tests for a given health state should measure the same functional ability variable in the same units, which allows comparison of outcomes between questionnaires and interpretation of the results on the same scale. The therapist or physician can use any instrument for measurement, but the instrument requires transformation and calibration of observations/measures to be expressed in a standard unit of functional ability. Any instrument with calibrated items then could be used to map G-code modifiers. In the appendix, a description of how to calculate the standard unit of functional ability from the questionnaires is described.

According to Medicare, if multiple tests are evaluated for a patient, all scores must be combined into a composite variable to create one G-code severity modifier2. Each test provides information about the patient’s functional ability over some range and a combination of tests could extend the range of measurement. But tests using different observation methods and indicators cannot be directly compared on the same scale. All test results would have to be transformed to measures of the same functional ability variable on a common scale as described here, before a single measure could be estimated from the multiple measures.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

The primary limitation is the method of the approach of this study. Most patient self-report instruments allow skipping or not responding to items and therefore have missing data. When that occurs, precision in the transformation is reduced (as seen in the scatter plots in Figures 2 and 4).

CONCLUSIONS

This paper provides an application of the principle of using equated scales for comparison across measures of LVR, but can be applied to any area of rehabilitation. Patient self-report, performance measures, and therapist judgments can be transformed to measures of the patient’s functional ability on the same equal interval scale before estimating G-code severity modifiers. This approach will make submitting meaningful analyses of the cost-effectiveness of rehabilitation from G-code and severity modifiers to support Medicare claims possible.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: National Eye Institute, NIH EY012045 and EY018696 grants and Reader’s Digest Partners for Sight Foundation grant.

The authors are grateful to Craig Velozo, PhD, OTR, Director and Professor of the Division of Occupational Therapy Medical University of South Carolina for providing raw data for the SRAFVP and to Joan Stelmack, OD, MPH, Director of Low Vision Service at the University of Illinois Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Science and Low Vision Supervisor at the Hines VA Blind Rehabilitation Center for providing raw data VA LV VFQ. No compensation was provided for such contribution.

Abbreviations

- ADVS

Activities of Daily Vision Scale (ADVS)

- AI

Activity Inventory

- LVR

Low Vision Rehabilitation

- LVROS

Low Vision Rehabilitation Outcome Study

- NEI VFQ-25

National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire

- SRAFVP

Self-Report Assessment of Functional Visual Performance

- VA LV VFQ

Veterans Affairs Low Vision Visual Functioning Questionnaire

- VAQ

Visual Activities Questionnaire

- VF-14

Index of Visual Functioning (VF-14)

- VFQ

visual function questionnaire

APPENDIX

How to calculate the standard unit of functional ability from the questionnaires is described in this paper using an Excel spreadsheet:

-

Step 1: enter the response rank score for each item in column A (leave the cell blank if there is no response to the item)

Rank scores by difficulty: where the minimum score should be assigned to the most difficult category and the highest score gets assigned to the easiest category.

-

Step 2: Calculate the average raw score

Where “n” is the number of items in the test

-

Step 3: Calculate visual ability

Where “minimum raw score” is the lowest rank score you can get and “maximum raw score” is the highest rank you can get.

Note: b0 and b1 are found from Table 2

Step 4: Take the output and compare to the Table 1 to determine which G-code modifier

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Robert Massof was a consultant to Alcon

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Tiffany L. Chan, Email: tchan25@jhmi.edu.

Monica S. Perlmutter, Email: perlmutterm@wusm.wustl.edu.

Melva Andrews, Email: AndrewsMP@uthscsa.edu.

Janet S. Sunness, Email: jsunness@gbmc.org.

Judith E. Goldstein, Email: jgolds28@jhmi.edu.

Robert W. Massof, Email: bmassof@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1. [Accessed 14 Jan 2015];American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Patterns Vision Rehabilitation. http://one.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/vision-rehabilitation-ppp--2013.

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, US Department of Health and Human Services. Program memorandum: intermediaries/carriers: provider education article: Medicare coverage of rehabilitation services for beneficiaries with vision impairment. 2002 May 29; Transmittal AB-02-078. Also available: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/Downloads/R165BP.pdf.

- 3.MLN Matters MM 8005 (Revised) Related to CR 8005 and Transmittals R165BP, R2622CP: Implementing the Claims-Based Data Collection Requirement for Outpatient Therapy Services – Section 3005 (g) of the Middle Class Tax Relief and Jobs Creation Act (MCTRJCA) of 2012. Also available: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/Downloads/MM8005.pdf

- 4.Mediware. [Last accessed 31 January, 2015]; website: http://www.mediware.com/rehabilitation/tools/item/g-code-conversion-calculator.

- 5.Velozo CA, Warren M, Hicks E, Berger KA. Generating clinical outputs for self-reports of visual functioning. Optom Vis Sci. 2013 Aug;90(8):765–75. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher WP, Harvey RF, Taylor P, et al. Rehabits: A Common Language of Functional Assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995 Feb;76(2):113–22. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stelmack JA, Szlyk JP, Stelmack TR, et al. Psychometric properties of the Veterans Affairs Low-Vision Visual Functioning Questionnaire. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004 Nov;45(11):3919–28. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stelmack JA, Tang XC, Reda DJ, et al. Outcomes of the Veterans Affairs Low Vision Intervention Trial (LOVIT) Arch Ophthalmol. 2008 May;126(5):608–17. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.5.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massof RW, Ahmadian L, Grover LL, et al. The activity inventory: An adaptive visual function questionnaire. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(8):763–774. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181339efd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massof RW. A Clinically Meaningful Theory of Outcome Measures in Rehabilitation Medicine. J Appl Meas. 2010;11(3):253–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massof RW, Hsu CT, Baker FH, et al. Visual Disability Variables. I: The Importance and Difficulty of Activity Goals for a Sample of Low-Vision Patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(5):946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massof RW, Hsu CT, Baker FH, et al. Visual Disability Variables. II: The Difficulty of Tasks for a Sample of Low-Vision Patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(5):954–967. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein JE, Massof RW, Deremeik JT, et al. Baseline traits of low vision patients served by private outpatient clinical centers in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012 Aug 1;130(8):1028–37. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein JE, Chun MW, Fletcher DC, et al. Visual Ability of Patients Seeking Outpatient Low Vision Services in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 Oct;132(10):1169–77. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massof RW. An Interval-Scaled Scoring Algorithm for Visual Function Questionnaires. Optom Vis Sci. 2007 Aug;84(8):690–705. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31812f5f35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]