Highlights

-

•

Key learning points.

-

•

Treatment of the shock state while searching for the possible cause is essential in trauma patient.

-

•

Bleeding into the subcutaneous plane is underestimated cause of hypovolemic shock.

-

•

Treatment of closed degloving lesions depends on the size and duration of the lesions.

Keywords: Injury, Shock, Subcutaneous

Abstract

Introduction

Hemorrhage is the most common cause of shock in injured patients. Bleeding into the subcutaneous plane is underestimated cause of hypovolemic shock.

Presentation of case

Unrestrained male driver involved in a rollover car crash. On examination, his pulse rate was 144 bpm, blood pressure 80/30 mmHg, and GCS was 7/15. His right pupil was dilated but reactive. Back examination revealed severe contusion with friction burns and lacerations. A Focused Assessment Sonography for Trauma (FAST) was performed. No free intraperitoneal fluid was detected. CT scan of the brain has shown right temporo-parietal subdural hematoma and extensive hematoma in the deep subcutaneous soft tissues of the back. Decompressive cranicotomy and evacuation of the subdural hematoma was performed. On the 4th postoperative day, three liters of dark brown altered blood was drained from the subcutaneous plane.

Discussion

The patient developed severe hypovolemic shock and our aim was to identify and control the source of bleeding during the resuscitation. The source of bleeding was not obvious. Severe shearing force in blunt trauma causes separation between the loose subcutaneous tissues and the underlying relatively immobile deep fascia. This is known as post-traumatic closed degloving injury. To our knowledge this is the first reported case in the English Literature with severe subcutaneous hemorrhage in blunt trauma patients without any previous medical disease.

Conclusion

Bleeding into the subcutaneous plane in closed degloving injury can cause severe hypovolemic shock. It is important for the clinicians managing trauma patients to be aware this serious injury.

1. Introduction

Road Traffic Collisions (RTC) is major health and economic burden all over the world. The main victims of RTC are the young productive population. The patients usually suffer multiple injuries that differ according to the biomechanics of the collision [1]. Care of the patient with shock can be one of the most challenging issues in trauma patients. Hemorrhage is the most common cause of shock in injured patients [2]. Bleeding into the subcutaneous plane is underestimated cause of hypovolemic shock [3]. Herein we are report a case of young man who was involved in RTC and developed severe hypovolemic shock. It was due to closed degloving injury of his back skin with extensive subcutaneous hemorrhage.

2. Case report

A 19-year-old unrestrained male driver was involved in a rollover car crash. He was ejected around 30 m away from the car. In the Emergency Department, his pulse rate was 144 bpm, blood pressure 110/70 mmHg, and respiratory rate was 44/min. His GCS was 7/15 and the right pupil was dilated but reactive to light (4 mm in diameter). Chest examination revealed decreased air entry on the right side. Abdomen was soft and pelvis was clinically stable. Back examination revealed severe contusion mainly on the right side of the back of the chest and left flank with friction burns and lacerations (Fig. 1). No past history of chronic medical diseases.

Fig. 1.

Severe contusion and friction burn over the back of the patient.

The patient was immediately intubated. Chest X-ray has shown right sided hemopneumothorax and a chest tube was inserted. Around 200 ml of blood was drained.

Suddenly, the patient becomes hypotensive with blood pressure of 80/30 mmHg. A Focused Assessment Sonography for Trauma (FAST) was performed. No free intraperitoneal fluid was detected. The IVC was flat and the heart was hyper contractile. No pericardial effusion was detected. Patient has neither pelvic nor long bone fracture. The patient received three units of packed red blood cells (RBCs) and four liters of crystalloids during the early phase of resuscitation.

A decision was taken to transfer the patient for rapid CT scan of the brain and cervical spine on the way to operating theater for cranictomy and possible diagnostic laparoscopy. CT scan of the brain has shown right temporo-parietal subdural hematoma (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

CT scan of the brain shows right temporo-parietal subdural hematoma (arrow).

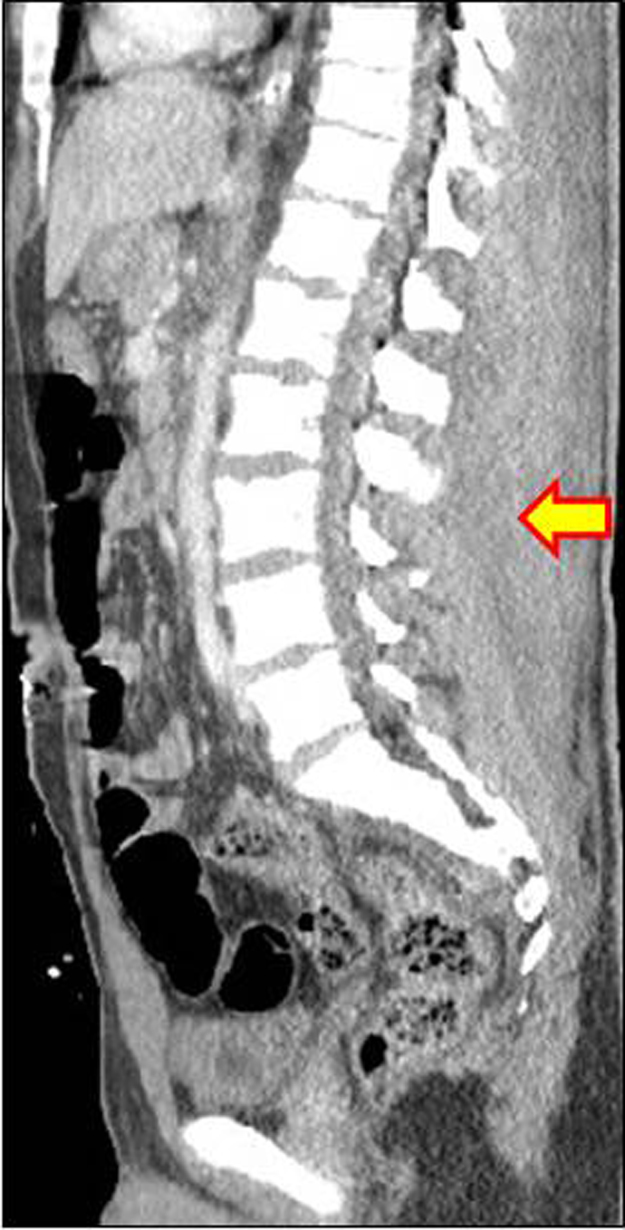

Right fronto-temporo-parietal decompressive cranicotomy and evacuation of the subdural hematoma was performed. The patient received further four units of packed RBCs during the operation. On table, a repeated abdominal ultrasound has shown minimal free fluid in Morrison pouch and pelvis. A diagnostic laparoscopy has shown a right side retroperitoneal hematoma with minimal hemoperitonium. Increased swelling in the right flank was noticed at the end of the operation. Trauma CT scan has shown stable fracture of the 1st, 3rd and 5th thoracic vertebrae, fracture of the right transvers process of all lumbar vertebrae, right sided retroperitoneal hematoma, and extensive hematoma in the deep subcutaneous soft tissues of the back (Fig. 3). No contrast extravasation was detected. In the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) the patient received three units of packed RBC and he remains hemodynamically stable.

Fig. 3.

Sagittal reformatted CT scan of the abdomen shows extensive hematoma between the subcutaneous fat and the paraspinal muscles (arrow).

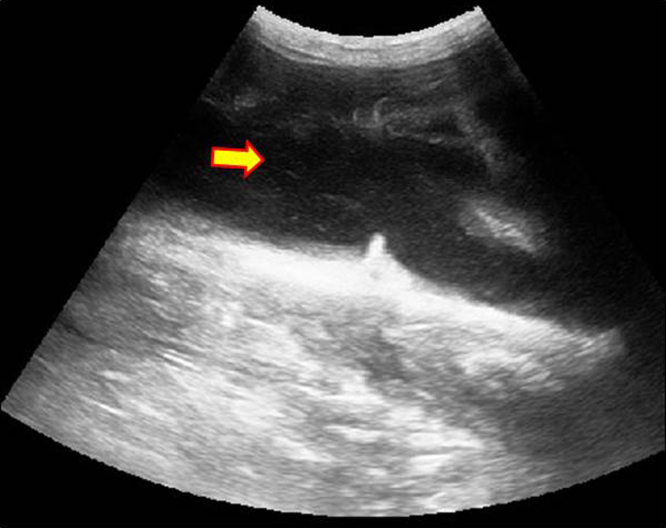

On the 4th postoperative day, a huge soft fluctuant swelling all over the back was noticed (Video 1). Ultrasound scan has shown cystic swelling involving the whole back with depth of about 7 cm (Fig. 4). Percutaneous suction drainage was performed. Three liters of dark brown altered blood was drained from the subcutaneous plane. Replacement of the skull bone flap with dural graft reconstruction was performed on the 13th post-operative day. Post-operative period was uneventful and the subcutaneous swelling resolved completely.

Fig. 4.

Ultrasound image of the back showing a hypoechoic fluid collection (arrow) and hyperechoic nodules corresponding to remnants of fat (arrow head).

3. Discussion

It is important in managing injured patient to recognize the presence of the shock state and to initiate the treatment during identification of the possible cause. The initial evaluation and treatment of our patient followed the Advanced Trauma Life Support Program guidelines [2].

The patient developed hypovolemic shock and our aim was to identify and control the source of bleeding during the resuscitation. Even after the decompressive cranicotomy and diagnostic laparoscopy, the source of bleeding was not obvious. Trauma CT scan with IV contrast was performed to identify the source of bleeding and possible angio-embolization if needed.

Post traumatic extensive hematoma in the deep subcutaneous soft tissues is a rare condition [4].

Severe shearing force in blunt trauma causes separation between the loose subcutaneous tissues and the underlying relatively immobile deep fascia [5]. This is known as post-traumatic closed degloving injury (also known as Morekl-Lavallee effusion) [4]. Separation of the two planes will create a cavity (dead space) in between [6]. The disrupted blood vessels crossing in between the two planes may continue to bleed and fill up the cavity with blood and lymph [7].

The closed degloving injury is commonly found adjacent to bony prominence with the classical location being over the greater trochanter of femur [8]. This lesion tends to be missed in the early phase if there is gradual accumulation of the blood, lymph, and liquefied fat [9].

The amount of accumulated blood depends mainly on the degloved area and the rate of bleeding into this potential dead space. In our patient, the degloved area included the whole back of the patient. Within a short period of time, the hematoma extended to the right flank.

The amount of blood that was drained by the chest tube, minimal free intraperitoneal blood, and the retroperitoneal hematoma were not large enough to explain this degree of hypovolemic shock. We think that the bleeding into the subcutaneous plane was the main cause for the hypovolemic shock.

During the initial assessment, the mechanism of injury, large bruises in the back, and absence of obvious source of severe bleeding, should give clue to the diagnosis. Early diagnosis with immediate blood and fluid replacement therapy were essential to save the patient's life.

There are several publications about post-traumatic closed degloving injury, mostly coming from orthopedic and plastic surgery experiences [5,7,8]. Massive bleeding into the subcutaneous plane has been reported in the literature due to different medical causes [9]. To our knowledge this is the first reported case in the English Literature with severe subcutaneous life threatening hemorrhage in blunt trauma patients without medical diseases.

Treatment of closed degloving lesions depends on the size and duration of the lesions [10].

Small size acute lesions can be treated conservatively with compression bandage [3]. For chronic and large size lesions, initial attempts should include percutaneous aspiration or suction drainage, with or without sclerodesis to obliterate the potential dead space. Doxycyline solution (500 mg of doxycylin powder dissolved in 25 ml of NaCl 0.9%) has been used for sclerodesis. It should be installed into the subcutaneous plan following aspiration of the fluids, then the solution is completely re-aspirated after one hour and tight elastic compression bandage is applied [11]. Other sclerosing agents that can be used; absolute alcohol, talc, and tetracycline [12].

Persistent and infected lesions may require repeated debridement, vacuum sealing dressing, or even skin grafting [6].

4. Conclusion

Bleeding into the subcutaneous plane in closed degloving injury can cause severe hypovolemic shock. It is important for the clinicians managing trauma patients to be aware this serious injury.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest among all the authors.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

N/A.

Consent of patient

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

Hefny A: study concept data collection, interpretation, writing the first draft and editing the paper.

Kaka L: study concept, interpretation, editing the paper.

Salim E: study concept, interpretation, editing the paper.

Al Khoury N: study concept, interpretation, editing the paper.

Guarantor

All the authors are responsible for the article

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.08.035.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

A huge soft fluctuant swelling all over the back.

References

- 1.Hinds J.D.1, Allen G., Morris C.G. Trauma and motorcyclists: born to be wild, bound to be injured? Injury. 2007;38:1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Surgeons . 9th ed. American College of Surgeons; Chicago, IL: 2012. Advanced Trauma Life Support For Doctors. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawkar A.A., Swischuk L.E., Jadhav S.P. Morel-Lavallee seroma: a review of two cases in the lumbar region in the adolescent. Emerg. Radiol. 2011;18:495–498. doi: 10.1007/s10140-011-0975-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gummalla K.M., George M., Dutta R. Morel-Lavallee lesion: case report of a rare extensive degloving soft tissue injury. Ulus. Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2014;20:63–65. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2014.88403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahara S., Oe K., Fujita H., Sakurai A., Iwakura T., Lee S.Y., Niikura T., Kuroda R., Kurosaka M. Missed massive Morel-Lavallee lesion. Case Rep. Orthop. 2014;2014(March (30)):920317. doi: 10.1155/2014/920317. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonilla-Yoon I., Masih S., Patel D.B., White E.A., Levine B.D., Chow K., Gottsegen C.J., Matcuk G.R., Jr. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg. Radiol. 2014;21:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s10140-013-1151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong B., Zhang C., Luo C.F. Percutaneous drainage of Morel-Lavallée lesions when the diagnosis is delayed. Can. J. Surg. 2014;57:356–357. doi: 10.1503/cjs.034413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller J., Daggett J., Ambay R., Payne W.G. Morel-Lavallée lesion. Eplasty. 2014;14:ic12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo M1 B., Pennell K.N., Lipscomb R.M. Life-threatening subcutaneous hematoma. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2008;26:522. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.09.005. e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nickerson T.P., Zielinski M.D., Jenkins D.H., Schiller H.J. The mayo clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:493–497. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bansal A., Bhatia N., Singh A., Singh A.K. Doxycycline sclerodesis as a treatment option for persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions. Injury. 2013;44:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penaud A., Quignon R., Danin A., Bahé L., Zakine G. Alcohol sclerodhesis: an innovative treatment for chronic Morel-Lavallée lesions. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2011;64:e262–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A huge soft fluctuant swelling all over the back.