Highlights

-

•

Fingertips are easily injured with various extents of soft tissue damage.

-

•

Delayed and inadequate treatment of nail bed injuries may cause substantial clinical problems.

-

•

The aim of this case report is to increase awareness about nail bed injuries among physicians who often treat these patients.

-

•

Absence of a fracture does not exclude nail bed injuries.

-

•

Adequate initial assessment and treatment are important to achieve the functional and cosmetic outcomes.

Keywords: Blunt trauma, Nail bed, Distal Phalanx, Fingertip injuries

Abstract

Introduction

A stable, mobile and sensate fingertip is of paramount importance to perform daily tasks and sense dangerous situations. Unfortunately, fingertips are easily injured with various extents of soft tissue damage. Delayed and inadequate treatment of nail bed injuries may cause substantial clinical problems. The aim is to increase awareness about nail bed injuries among physicians who often treat these patients.

Presentation of case

We present a 26-year-old male with blunt trauma to a distal phalanx. Conventional radiographs showed an intra-articular, multi-fragmentary fracture of the distal phalanx. At the outpatient department the nail was removed and revealed a lacerated nail bed, more than was anticipated upon during the first encounter at the emergency department.

Discussion

Blunt trauma to the fingertip occurs frequently and nail bed injuries are easy to underestimate. An adequate emergency treatment of nail bed injuries is needed to prevent secondary deformities and thereby reduce the risk of secondary reconstruction of the nail bed, which often gives unpredictable results.

Conclusion

However, adequate initial assessment and treatment are important to achieve the functional and cosmetic outcomes. Therefore awareness of physicians at the emergency department is essential.

1. Introduction

Fingertips are an essential part of the human body and are used to explore our surroundings and provide danger warning signs. In addition, stable, mobile and sensate fingertips are needed to perform activities of daily living. With the recent increase in the use of touchscreen in smartphones, tablets and remote controls, the fingertip is needed more than ever for those delicate movements. In addition the fingertip is important for the overall function of the hand and cosmetic impairment can have an enormous social impact [1,2].

Fingertip and nail bed injuries are seen at all ages, with a peak incidence in 4–30 years old patients. Patients are most often initially treated by family doctors or physicians at the emergency department [1,3,4]. Chang et al. reported that 10% of all the accidents encountered in the emergency department involve the hand. In case of fingertip injuries the nail bed is damaged in 15–24% of the cases [3]. Fingertip injuries are defined as any injury to the distal phalanx, including soft tissue, nail plate, nail bed, tendon and bone [1,4]. In most cases a combination of injured structures is present.

Fingertip injuries are caused by sharp or blunt trauma. Sharp trauma (amputations), for example with knives or cutting machines, is less common and the extend of the injury, especially involvement of the nail bed, is relatively easy to identify. In contrast, more often, injuries are due to blunt trauma (e.g. crush injuries by doors, heavy machinery or during sports) [5]. This type of injury results in compression of soft tissue, mainly the nail bed, between the nail and the underlying bone in addition to the external forces. The extend of soft tissue damage can easily be underestimated and often the nail bed is injured.

Nail bed injuries may vary from subungual hematomas, lacerations and avulsions of matrix tissue. Currently there is an ongoing debate about whether or not to remove the nail and inspect the nail bed after blunt trauma. Inspection of the nail bed is important in order to appreciate the extent of the injury. However, not every needs to be removed. If lacerated, it is important that the nail bed will be repaired adequately and with attention to detail as inadequately treated nail bed injuries lead to loss of function and pain, which have an enormous impact on the patient [1,6]. It is recommended that in repairing the nail bed a loupe magnification and the use of micro (vascular) instruments are used. Sometimes early intervention by a dedicated hand surgeon is necessary to achieve better functional and aesthetic outcomes [1].

The aim of this report is illustrate the clinical problem of nail bed injuries by means of a case description. In addition, we will provide guidelines for physicians encountering blunt fingertip injuries highlighting the importance of early identification and treatment of nail bed injuries.

2. Case report

A 26-year-old healthy male presented himself at the Emergency Department (ED) with an injured fingertip after blunt trauma sustained during a field hockey game. Inspection of the fourth digit of the right hand revealed isolated fingertip injury. Both proximal and middle phalanx were unaffected. A laceration of two centimeters was identified at the volar/ulnar side of the fingertip. The nail was partially loose, and the nail bed seemed more or the less intact. There was no loss of sensation and all movements in the distal interphalangeal joint were possible, but limited due to pain (Fig. 1A). Plain radiographs showed an intra-articular, multi-fragmentary fracture of the distal phalanx with a congruent distal interphalangeal joint (Fig. 1B, C). Further examination under local “oberst” anesthesia confirmed no problems with flexion and extension of both the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints. As a first treatment, the laceration was sutured with transcutaneous interrupted stiches after which the fingertip regained a normal aspect. Antibiotics were prescribed, because of the extended nature of the fracture and soft tissue damage. The patient was scheduled for an appointment at the outpatient department the next day. This physician identified the injury as a “high risk injury” for nail bed involvement based on the laceration and the fracture. The patient was directly scheduled for a nail bed repair in the operation room the same day. After removing the nail, the extent of the nail bed injury became apparent and was much greater than anticipated by the physician on the by the physician on the ER department the day before. Multiple lacerations were identified and the nail bed was repaired with interrupted sutures. Prolene 6.0 was used as suture material (Fig. 1D). The nail was replaced and fixated by proximal and distal sutures with Ethilon 5.0 (Fig. 1E) to function as a splint and natural cover for 2 weeks. Postoperative radiographs showed a nearly anatomical reposition of the intra-articular multi-fragmentary fracture of the distal phalanx. After 2 weeks the nail and the sutures were removed. Thereafter, the fingertip was protected by a small splint. During follow-up no postoperative complications were encountered. The nail bed recovered completely and the nail plate seemed to develop without any deformities (Fig. 1F). Seven months after the initial trauma there are no complaints about pain or loss of function during daily activities.

Fig. 1.

A = Clinical picture of the initial trauma; B + C = X-ray of the initial trauma; D = peroperative image of the nail bed; E = peroperative image of the nail; F = postoperative image after a 7-month follow-up.

3. Discussion

Patients with blunt trauma of the fingertip are mostly encountered by family doctors and emergency physicians [1,3]. Although many injuries require relative simple treatments, nail bed injuries are easily overlooked. If treated inadequately secondary deformities will occur if explained below. It remains difficult to assess the extent of the injury in swollen, painful and bloody fingertips, especially in children as they are less cooperative and less suitable for local anesthetic ring block to aid inspection [6]. Furthermore, an intact nail makes it impossible to assess the damage of the nail bed without removing the nail [6]. In case of nail bed hematomas covering more than 50% of the nail bed without evidence of a fracture and intact nail and nail edges, it is sufficient to evacuate the hematoma through a cauterized hole and leave the nail in place. However, bear in mind that nail bed lacerations may be present in this clinical situation the resulting scar tissue of an unrepaired nail bed laceration can cause deformity and make the patient prone to repetitive infections. The nail plate should be removed in the presence of a nail bed hematoma more than 50% in combination with an intact nail and nail edges, but with a fracture or a visible nail bed laceration [7].

The basic principles in treatment of nail bed injuries after blunt trauma are sufficient cleaning, minimal debridement of the nail bed, proper alignment of the injured structures, repair with the use of a loupe, micro instruments and small, thin needles with absorbable sutures, preservation of marginal skin folds, and an appropriate wound dressing [4,8]. Often the old nail or the Zimmer splint is applied to protect the nail bed and acts as a “splint” by holding open the nail fold and preventing scarring between the nail fold and the nail bed. However, there is no clear evidence to support this and it could be associated with a small riks of infection. Therfore, the results of the NINJA trial may results in change of clinical practice as they invest whether or not a splint is beneficial [9]. Injuries of the paronychium, which is the fold on both lateral aspects of the nail, and eponychium, referring to the dorsal skin on the dorsum of the nail, have to be repaired carefully. Eponychial loss can lead to a rough flat nail and can be treated sometimes with a graft from e.g. a toe [10]. If nail bed injuries are not treated well, secondary deformities can occur. A germinal matrix scar leaves a split or no nail growth. If the scar is on the sterile matrix, a split or detachment of the nail may occur distal to the injury. An adequate emergency treatment of nail bed injuries is needed to prevent secondary deformities (e.g. split nail or hook nail) and thereby reduce the risk of secondary repair of the nail bed, which often gives unpredictable results [2].

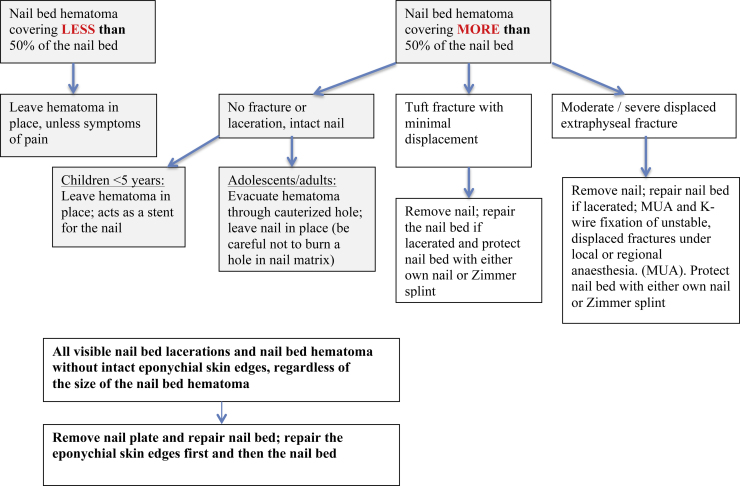

As early adequate treatment of nail bed injuries is important, we use an algorithm (Fig. 2) [7] to aid physicians in their decision about whether or not to remove the nail and inspect the nail bed. Initially asses the presence and extent of a subungual hematoma as this occurs often after blunt trauma [1]. In addition a plain radiograph should be made in every fingertip injury as a fracture of the distal phalanx indicates that the injury was caused by a sizeable force which also has an impact on soft tissue, increasing the chance of injuries needing surgical treatment [6]. However, the absence of a fracture does not exclude nail bed injuries. Both inspection and treatment can take place at the Emergency Department if the expertise and facilities are available. However, when in doubt, seek advice and or treat these injuries in the operation room.

Fig. 2.

An algorithm for the treatment of blunt fingertip injuries [7].

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Author contributions

G.L. Nanninga: writing the paper, study design.

K. de Leur: writing the paper.

A.L. van den Boom: literature research.

M.R. de Vries: surgeon of the patient, study design, final check.

T.M. van Ginhoven: study concept + design, writing the paper, final check.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Guarantor

G.L. Nanninga

T.M. van Ginhoven

M.R. de Vries

References

- 1.Yeo C.J., Sebastin S.J., Chong A.K. Fingertip injuries. Singap. Med. J. 2010;51(1):78–86. quiz 7. Epub 2010/03/05. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tos P., Titolo P., Chirila N.L., Catalano F., Artiaco S. Surgical treatment of acute fingernail injuries. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2012;13(2):57–62. doi: 10.1007/s10195-011-0161-z. Epub /10/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang J., Vernadakis A.J., McClellan W.T. Fingertip injuries. Clin. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006;5(2):413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.coem.2005.11.010. ix. Epub 2006/05/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw A., Findlay J., Kulkarni M. Management of fingertip and nail bed injuries. Br. J. Hosp. Med. (Lond.) 2011;72(8):M114–M118. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2011.72.sup8.m114. Epub 2011/08/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doraiswamy N.V. Childhood finger injuries and safeguards. Inj. Prev. 1999;5(4):298–300. doi: 10.1136/ip.5.4.298. Epub 2000/01/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giddins G.E., Hill R.A. Late diagnosis and treatment of crush injuries of the fingertip in children. Injury. 1998;29(6):447–450. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(98)00083-7. Epub 1998/11/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.B.J. Shore, P.M. Waters. Fingertip injuries in children. 2012 [cited 2013 03 october]; Available from: http://orthoportal.aaos.org/oko/article.aspx?article=OKO_PED040#abstract.

- 8.Weichman K.E., Wilson S.C., Samra F., Reavey P., Sharma S., Haddock N.T. Treatment and outcomes of fingertip injuries at a large metropolitan public hospital. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013;131(1):107–112. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182729ec2. Epub 2012/09/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.http://reconstructivesurgerytrials.net/clinical-trials/ninja/.

- 10.Bharathi R.R., Bajantri B. Nail bed injuries and deformities of nail. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2011;44(2):197–202. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.85340. Epub 2011/10/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]